3

Gracious Womanhood

IT IS SAID that the poet E. Pauline Johnson could transition before her captivated audience from “pure Indian” to “almost white,” simply through a change of clothing. This may speak to the cliché that the “clothes make the (wo)man.”1

In the only known video recording of Isabella Hardisty Lougheed, produced by Dr. Burwell James Charles,2 Isabella, dressed in European-inspired finery, posed in front of her grand home, Beaulieu. Unfortunately, the audio portion no longer exists, but Isabella is clearly directing the activity on the grounds. The recording is not dated; however, Isabella appears to be past middle age, and thus the filming was likely done sometime in the 1930s.3 She is of smaller stature, and her facial features reflect her Indigenous ancestry. Yet the majority of the press reports about Isabella, which often included elaborate descriptions of her attire, suggest the public persona of a woman who was not Indigenous but rather a woman who internalized the finer aspects of European-inspired gracious womanhood.

That she was able to internalize these finer aspects of graciousness does not negate the fact that Isabella became a political person, nor does it suggest she abandoned her Metis culture and history. In fact, Isabella proved adept at networking with the right people, and she demonstrated the diplomacy of an accomplished Hudson’s Bay Company chief factor. She became a recognized and important public figure in her own right, with newspapers commenting on her every move, from her dancing partners to her grand home and garden, to her family connections with HBC men.

That Isabella succeeded in constructing her persona as the gracious first lady of the North West (who was nonetheless a respected pioneer) is evident. It is also evident that Isabella and James formed a highly successful business partnership. Together they helped establish many of the community-building organizations and cultural venues that were necessary for the West to portray itself as progressive and sophisticated. Yet James was a staunch Methodist with roots in Protestant groups such as the Orangemen, and he had married a woman of Indigenous ancestry. Despite the social capital her kinship group provided, there was still a need to extend a social network that would include primarily Euro-North American political and business leaders and even British royalty. With James away so much of the time, the social networking in Calgary was often left in Isabella’s capable hands.

Isabella’s preparation for her life as the wife of a public figure began when she was just a young girl in northern fur trade country. At a young age, she was sent away for formal educationl, trained to be a gracious woman. Given that her father had retired to Lachine, Quebec (when Isabella was of marrying age), where many of the HBC officers retired, the plan was likely that Isabella would marry in the East, and the expectation was likely that her husband would be connected to the fur trade. It was in 1879 that Isabella had left the West for what she may have thought would be the last time. However, Isabella’s father died on 16 January 1881, and her mother married Edwin Stewart (also known as Stuart) Thomas, a man with far fewer connections than the Hardisty family, in Winnipeg, in August of 1883.4

It is not clear if Isabella was in Winnipeg with her mother between the time of her father’s death and her mother’s remarriage, or if she stayed in Lachine with other family members. The only indication that she was already separated from her mother was her comment made later to a newspaper, when Isabella said that her father’s death

necessitated the breaking up of our home, and on this occasion I came to Calgary to visit my uncle…I came here in 1882, and I never went east to live again, for I was married in 1884.5

If Isabella’s dates are correct and she arrived in Calgary in 1882, then she and her brothers Frank and Thomas came to live with their uncle, Richard Hardisty, one year prior to her mother’s marriage and one year after her father’s death.6

According to some sources, in 1882, when Isabella likely arrived to live with him, Richard Hardisty was the wealthiest man in the North West.7 The fact that he was so wealthy would have made the arrival of family members, and his niece in particular, noteworthy. As the North West was evolving from fur trade to sedentary economy, the arrival of young ladies was always a newsworthy event. As the local newspaper, the Calgary Herald, wrote, the appearance of these young ladies was akin to the arrival of “angels,” bringing joy to “especially those in the legal profession.”8 Reminiscing about those early days in Calgary, Isabella recalled,

Those were happy days. We used to ride miles and miles around—we knew everybody—girls were few and always very popular, and our social life centered around the homes and the church. My aunt was an ardent Methodist. She was the daughter of the Rev. George McDougall, the first Methodist Missionary in the west, and she was very keen to start a Methodist church. No building could be secured and my uncle finally managed to get a large tent.9

It was only a year after Isabella’s arrival at Calgary, that, in the late summer of 1883, her future husband, James Alexander Lougheed, moved from Medicine Hat to Calgary.10 Despite his Irish working-class background, when the ambitious young lawyer arrived in Calgary, James garnered a fair bit of attention. At a time when lawyers often served as brokers for business investments of all sorts, the Calgary Herald noted that James was seen as a “valuable acquisition to Calgary society.”11

Although he may have been a valuable acquisition to Calgary society, James Lougheed had a fairly humble background and he arrived in the West with few assets and influential connections. He was born in Brampton, Ontario, on 1 September 1854 to a Methodist family of Scottish and Irish descent. His father was a carpenter, a trade he hoped to pass along to James. The family resided in Cabbagetown, the poor eastern section of Toronto, which was English-speaking, Protestant, and highly British and Orange in sentiment and tradition. The Cabbagetown of Lougheed’s youth comprised

lines of utilitarian frame houses, largely covered over in roughcast plaster…thinly built, lacking central heating, and boasting privies out back…a drab industrial environment with dirt, debris and fumes of factories close at hand.12

His mother believed that James should aspire to more than carpentry,13 and she encouraged him to accept a position as assistant librarian at Trinity Church in Toronto. Trinity was sometimes referred to as “the Poor Man’s Church,” where parishioners were likely to be bricklayers, mariners, servants, and tavern keepers, with only a few listed as “gentlemen.”14 It was at this church, however, that James was encouraged by the Anglican layman, Samuel Blake (who went on to become a Member of Parliament)15 to further his education at Weston High School.

According to the Newsletter of the Lougheed Families of North America, James spent his spare time as a young man attending church meetings, listening to the speeches at the House of Parliament, or fulfilling his duties as chaplain in the Orange Order, duties that included donning a white gown and carrying a Bible in parades.16 There is no evidence of James continuing his involvement with the Orangemen when he later lived in Calgary, perhaps in part because he married an Indigenous woman with an influential kinship network.

While still in Ontario in 1877, James had studied law with the Toronto firm of Beatty, Hamilton and Cassels. In 1881, James opened his own law office in Toronto but only practised a short time before heading west in 1882 with his brother Sam. The 1880s were times of expansion in the North West, and James quickly gained an appointment to practise law in the Manitoba Court of Queen’s Bench and County Courts.17 James kept a diary for most of his adult life and, while the entries for the period when he was married to Isabella are not very detailed, the entries for his days in Winnipeg are more revealing of his personality. As a young man intent on making his fortune in the West, James was quite pleased to note everything from who preached the services to the amount he spent on his first suit, even noting in his diary the first time he wore the new suit.18 Although he was beginning to make some good connections in Winnipeg, James was not there long. When the Canadian Pacific rail line was completed to Medicine Hat in 1883, he soon travelled to the end of that line, where he set up a general store in a tent with business partner, Thomas Tweed.19 There is no official record of this, but Lougheed family history holds that, during this time, James reportedly met William Van Horne and secured a position as legal counsel for the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR).20

Whether he made this connection or not, in the late summer, James and his brother Sam moved to Fort Calgary,21 where James rented the back half of a log cabin for his legal practice. If James was not the first lawyer in Calgary, he quickly became the busiest.22 It did not take much time for the enterprising young man to make even more important personal connections. In December of 1883, James was elected as one of the first stewards of Central (Methodist) United Church “at the first meeting of the quarterly official board,” held at the home of Richard Hardisty.23 Soon after, James and Isabella became a couple. No doubt it was not only her important family connections that convinced James of Isabella’s suitability as a wife but also her Euro-North American education.

James’s marriage into the Hardisty family was fortuitous for him. Yet, according to some newspaper articles, James often attributed his success to his mother, Mary Ann Alexander, a “beautiful Christian woman…It is said that from her he inherited his Scotch shrewdness and cleverness that characterized him in later years.”24 Mary Ann Alexander, who had given her son the middle name of Alexander, died before James went west. Thus, unfortunately, she never witnessed her son’s tremendous success after he had forged ties with the Hardisty family.

Indeed, it had not taken James long after he arrived in the North West to become what some referred to as a “pedigreed Westerner through marriage” to Isabella.25 The social significance of the marriage on 16 September 1884 was clear when the Calgary Herald reported,

Last evening, the youth and beauty of our town might be seen wending their way to the Methodist Church, where a scene of no common interest was being enacted…Before the hour the building was packed, a number having to satisfy themselves with a peep through the windows. The principals were James Alexander Lougheed, Esq., Barrister, and Miss Isabella Hardisty.26

The invitations for James and Isabella’s wedding indicated that the event was organized by Richard Hardisty, with no mention made of Isabella’s mother. Whether or not Mary Hardisty was even at her daughter’s wedding is not clear, but the invitations requested the presence of guests at the Methodist Church and then at the home of Richard and Eliza Hardisty to celebrate the marriage of their niece.27 Newspaper reports were focused on the “youth and beauty” in attendance, so no mention is made of Isabella’s mother or siblings, if they were in attendance.

At least one author believes that the union between Isabella and James was sanctioned by the elders of the Hardisty family. Popular historian J.G. MacGregor wrote,

Evidently Dick Hardisty, keeping an eye on the budding romance (between Isabella and James) had made up his mind that his brother’s eldest daughter was making a good match. There is nothing to show how one of her other uncles, Donald A. Smith, regarded the union, but undoubtedly his interest in the affair would have boded well for the young couple.28

Regarding Richard Hardisty’s wealth and stature, MacGregor continued,

Whatever it cost Dick Hardisty to send his children away to school it made little dent in his wealth. Undoubtedly he was the richest man in the western prairies and besides his mill had his hand in several other ventures.29

Although MacGregor’s sources are sparse, Hardisty was well connected enough for it to be plausible that he was one of the wealthiest men in the West during the transitional period. In addition to his own stature as a chief factor, as a member of the McDougall family, because of his marriage to Eliza, Richard often employed and formed partnerships with other McDougall men, also a fairly wealthy group. In fact, recognizing the changing times, Richard worked “hand in hand with…David [McDougall] who competed with the Hudson’s Bay Company for trade.”30 This suggests that Richard was, at least by this time, a family man first and a company man second. After his marriage, family member James soon also became Richard’s close business associate.31

Despite the excitement generated by the marriage of the future senator to the daughter of fur trade aristocracy, James and Isabella still began married life in a small log hut next to James’s law office. The only renovation was a bay window, imported from Central Canada, a renovation that served as notice to the townspeople that this couple already viewed themselves to be “distinct.”32 It is not clear if this incident precipitated a move, but, according to popular historian Grant MacEwan, the bay window continued to be an object of interest and curiosity, until the day a runaway horse veered off what is now Stephen Avenue, plunged through the window, and “landed in the middle of Mrs. Lougheed’s front parlor.”33 The Lougheeds physically moved the house twice to new locations, until they finally left it to move into their grand home, Beaulieu, in 1891.34

Confirming Isabella had not married out of, but rather that James had married into an established Hudson’s Bay Company family, and as though he was now a company man himself, James had chosen HBC man Charlie Parlow to stand for him as best man. In fact, when James was interviewed in 1921, he indicated he had sensed a new beginning for himself as a “company man” upon his marriage. James said,

My wife was a Hardisty, of Lady Strathcona’s family, so that, in a way, I’m a Hudson’s Bay man, my father-in-law having been chief factor of the company. In early western days people spoke of “The Company” pretty much as a man from Prince Edward Island spoke in New York of “The Island,” and asked “What other Island is there?”35

James’s contemporaries noted that, when he ventured west, “Like most men who came to Calgary in those days he was not over burdened with surplus wealth.”36 Yet, by 1889, just six years after his arrival in Calgary, and subsequent marriage into the Hardisty family, the local paper could refer to James as “one of our heaviest real estate owners, having accumulated property to the extent of nearly $70,000 worth.”37 Given that the 1881 census does not even list Calgary, but rather a region identified as the Bow River, which contained “five shanties, seventy-five houses, and four hundred people, of whom fifty were women,”38 James and Isabella’s accumulation of property by 1889 was impressive.

While researching members of Isabella’s kinship network, historian Donald B. Smith located what he believed to be the earliest surviving letter written by James, dated 25 November 1885. Speaking about this letter, Smith wrote,

One can also see from this letter how the young lawyer has worked himself into the network of his wife’s influential family connections, who included not only Richard Hardisty, the richest man in the Northwest Territories, but also Donald A. Smith [aka Lord Strathcona], soon to be the richest man in Canada.39

In this letter to Richard Hardisty, James did give some indication of the close connection he quickly developed with Isabella’s uncle. After some personal details about his first-born son “growing like a weed in a potato field,” James went on to speak of other family members, referring to an upcoming visit by Lord Strathcona, the “worthy driver of the last C.P.R. Spike.” James also confirmed some of the investments he held with Richard Hardisty, in this case, cattle. In the same letter, James noted that his brother Sam was looking after the herd for Richard and James.40

Like James after him, Richard Hardisty was never elected as a representative of the North West in the Canadian government (although Richard had run unsuccessfully in the 1887 election before receiving his Senate appointment). Rather, both men took advantage of political connections, and were successful in part due to the long fur trade history of the Hardisty family. In fact, when Richard was appointed to the Senate in 1887, he continued to hold the position of Chief Factor for the Northern Department, comprising all of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and the Territories.41 The fact that Richard could retain his post as an HBC man at the same time as serve in the Senate demonstrates the continuing importance of the fur trade company and its employees and their family networks during the transitional period.

As both chief factor and the area’s senator, Richard was well placed to monitor changing times and to identify political and financial opportunities. According to the man who would eventually become a business partner to James, Edmund Taylor (another HBC man), it was Richard who had encouraged the HBC to expand its operation to include “Flour Mills, Lumber Mills, and caused the company to become the pioneer cattle ranchers in the North after the buffalo made their last trek southward about 1870.”42 As the senior HBC officer when settlers began arriving on the western prairies, Richard was ideally situated not only to assess material needs but also to profit personally from land speculation.

After Richard Hardisty’s death, even though James soon assumed his uncle’s Senate post, James and Isabella relied on Donald A. Smith as the senior patriarch of the Hardisty family. Indeed, Smith was a good connection to have, given that he was not only a friend and confidant of Sir John A. Macdonald but one of the principal shareholders of the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Canadian Pacific Railway, and the Bank of Montreal.43 Not only had James stepped into the Senate seat of his wife’s uncle, but soon after his marriage he was appointed to serve as solicitor for these three companies, which helped propel Donald A. Smith to immense wealth. Thus, it was soon after his own Senate appointment on 15 October 1889 when James and Isabella’s status in the North West was truly and very publicly confirmed.44

When Senator Richard Hardisty died in 1889 as the result of a wagon accident in Saskatchewan, James, still only thirty-five years old, was considered to be his natural successor by people who were well placed themselves. In a letter to John A. Macdonald, Reverend Leonard Gaetz, Red Deer’s Methodist minister, who was a fairly wealthy land owner and fur trader by then, wrote,

James Lougheed is a gentleman of culture, ability and position, with a thorough knowledge of, and faith in, Alberta. He is a Conservative of Conservatives, a good address, and will make a first class representative.45

In reality, Gaetz’s first connection in the North West was not to James but to Richard Hardisty, who had helped Gaetz find a homestead in the agriculturally rich area surrounding the Red Deer River.

It is true, though, that in addition to Gaetz and the connection to the Hardisty family, Lougheed had managed to make some connections of his own. He was a personal friend of Minister of the Interior Edgar Dewdney and, while in Toronto, had also worked to help John A. Macdonald gain re-election in 1878, through his involvement with the Young Men’s Conservative Club.46 Although he followed the promise of success to what would become Alberta, it was said that James

never forgot the traditions of the staunch old Conservative East Toronto…and, while advocating changes, he always made it plain that in his opinion the Conservative party was a true friend of the North-West…Even before 1887, when representation was given to the North West in Parliament, a Conservative Association was formed in Calgary in 1884, of which Mr. Lougheed was one of the founders and active members.47

It should be no surprise, then, that James always remained loyal to Macdonald during the volatile times in the 1880s, and also that he became a prominent investor in the Conservative organ, the Calgary Herald.48

After Richard Hardisty’s death and his own political appointment, James acknowledged his new role as an up-and-coming patriarch in the Hardisty family, and the youngest man in the Senate chamber. In a letter to Richard’s widow, James thanked her for her congratulations on his new post as senator and noted that he hoped the

mantle of poor Mr. Hardisty, which has fallen upon me may be worn by me as worthily as it was by him. Should you ever consider that I can be of any service to you in my new position do not fail to command me in any way.49

Of course, it was not only James who became quite adept at picking up the mantle left by Richard when the North West experienced tremendous growth. According to news reports, both James and Isabella entertained on a regular basis from the very beginning of their married life. As Isabella recalled years later,

Those were the days of the real western hospitality. Every New Year the men called at our homes and we used to receive from 9 A.M. until midnight, sometimes having a hundred callers. There were many privations too but we were young and did not mind them.50

In this excerpt, Isabella refers to the custom of receiving guests on the first day of every New Year, a custom she experienced first as a young girl at the “Big House” in the North. She clearly remembered the privations of her early married years as well, though, as she had also remembered the privations she had faced in the North.

However, the privations for James and Isabella as a married couple in Calgary were relatively short lived. As a symbol of their role as members of the aristocracy of the new West, shortly after James’s appointment to the Senate in 1889, the couple began to plan the building of their grand home, Beaulieu, to which they moved in December of 1891. The sandstone mansion, located at present-day 13th Avenue and 7th Street SW, necessitated the services of Ottawa architect, James R. Bowes. It generated much attention, and, soon after its completion, the Lougheeds’ grand home was profiled in the Calgary Weekly Herald’s “The buildings of 1891.”51 The Calgary Tribune described the lavish housewarming held on 16 February 1892, when James and Isabella hosted 150 guests, the “cream of Calgary and Alberta society.”52

According to some assessments, the imposing mansion was to be an “ostentatious symbol of the new prairie wealth.” James and Isabella went to such extravagances as to seek out marble cutters from Italy to build the eight fireplaces housed in Beaulieu.53 Construction did what it was meant to do—boost the sophistication of not only the Lougheeds but also the new West. Beaulieu drew national attention, with detailed descriptions in both the Toronto Mail and the Toronto Globe.54 Whatever the reasons behind the naming of their new mansion as Beaulieu, the extravagance was very likely meant to demonstrate the importance of the up-and-coming aristocratic and soon to be “Lady” Isabella and “Sir” James. With its “rugged sandstone walls, irregular roof line, projecting towers, iron cresting, lacy balustrades and tall chimneys,” Beaulieu clearly had established new standards of elegance and sophistication, revealing not only how far the town had come in such a short time but also how far James and Isabella themselves had come.55

In addition to the establishment of a new mansion, James and Isabella’s family was growing. On 29 July 1885, they welcomed their first son, and his name, Clarence Hardisty Lougheed,56 served as notice of the continuing importance of the Hardisty connection.57 On 3 February 1889, another son, Norman Alexander, was born.58 Alexander may have been chosen as Norman’s second name in honour of James’s mother, Mary Ann Alexander. However, two of Isabella’s brothers also shared the middle name Alexander, and thus it seems the name held some significance for the Hardisty family as well. On 19 December 1893, the couple’s third son, Edgar Donald, was born.59 Again, the middle name was no doubt drawn from the Hardisty kinship network, and arguably a man who would become its most influential member, Donald A. Smith. On 22 August 1898, Isabella and James welcomed their first daughter, Dorothy Isabelle, whose middle name was chosen in honour of Isabella’s aunt, Lady Strathcona. A fourth son, Douglas Gordon, was born on 3 September 1901. In this son’s case, there is no known link to the Hardisty family for the second name. The final child, Marjorie Yolande, was born on 21 February 1904. “Yolande” is an interesting choice, given that it was more commonly bestowed upon French girls. 60

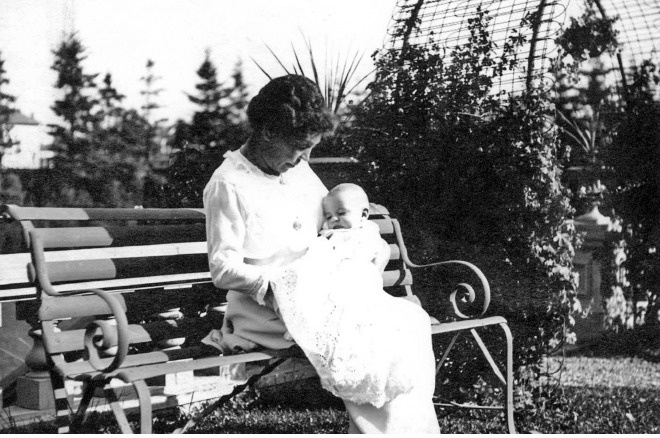

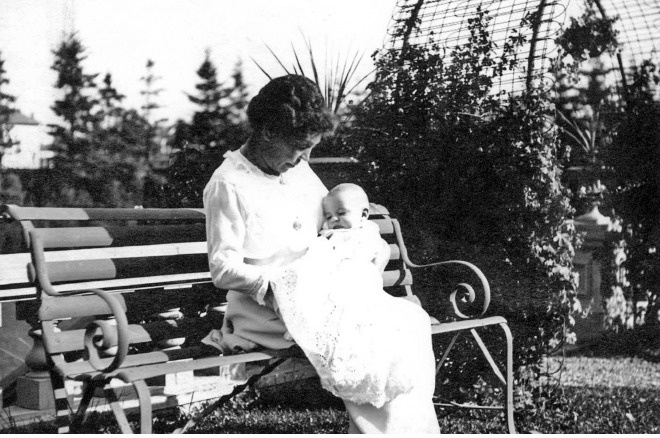

Isabella as a young mother. Photo undated. Lougheed House National Historic Site Archives.

The role of mother was one of many that Isabella assumed, along with wife, colleague, employer, patron, leader, and hostess. However, despite these roles, many of them very public, the first researchers with Lougheed House National Historic Site, Trudy Cowan and Jennifer Bobrovitz, observed that Isabella was a “private person,” and that knowing her “remains a challenge.”61 It is true that she left few personal documents and that there are no descendants remaining who have extensive personal memory of Isabella and James. However, by the time written records were more common, there were some family members who had specific memories. For example, the late Peter Lougheed (who served as Alberta’s premier from 1971 to 1985), while having no memory of James, did recall for a local newspaper in 2001, in an article appropriately titled “A Daughter of the West Who Made a Difference,” that his grandmother was an

“elegant woman in a rocking chair living out her last few years in the old house…She was elderly when we knew her,” says Peter who was only eight when his grandmother died. “My main memory of her is her comment on my name. ‘Peter. It’s funny you named him Peter. That’s the name of our dog.’”62

During the same interview, Donald, Peter’s brother and three years his senior, recalled Isabella talking to him about those who viewed Metis leader Louis Riel as a hero: “She told me about her brother who was killed at Batoche…I remember her talking about Riel…She would be terribly upset with all this talk of Riel today.”63 The reporter’s interview with Peter and Donald led him to Norman Lougheed Jr., who was eighty-six years old at the time and living in Sidney, British Columbia, and the oldest surviving descendant of Isabella and James.

Norman Jr. lived with Isabella at Beaulieu until her death, and thus was a good primary source of information. Norman’s mother, Mary Stringer Lougheed, was often present at the functions at Beaulieu, and knew Isabella fairly well.64 Norman recalled that Mary had observed that Isabella was an excellent and gracious hostess, who had a “profoundly beneficial effect” on the senator, “guiding him socially and culturally into new worlds.” Mary had even concluded that Isabella was the “driving force behind James.”65 Another family member, Flora, Norman Jr.’s wife, shared her opinion with the reporter at the time that Isabella

was a tyrant…She was definitely in charge. Mary talked a lot about her, and about how strict she was. Mary knew a lot about entertaining—she learned it from Granny, who was an excellent hostess, a gracious hostess. There’s no doubt she was made of good stuff.66

Perhaps it was Flora’s detailed memories that best described Isabella, the “gracious” woman in charge but no doubt made of “good stuff.”

Although Mary had told Flora that Isabella was the driving force behind the partnership, according to Bobrovitz, speaking to the Calgary Herald in 2001, James and Isabella worked as a team: “Individually, they could not have been as successful as they were collectively.”67 Bobrovitz’s assessment, though made by a popular journalist, is nonetheless useful in understanding Isabella’s history. James and Isabella were immensely successful as they worked collectively to build upon the prestigious position of the Hardisty family in the transitional economy.

In fact, it appears James always maintained an attitude of pragmatism when it came to marriage and the partnerships that would lead to the most success. As a young boy attending school in Ontario, James is said to have replied to a request to define marriage with the following assessment: “Marriage—ah—is a corporation of two persons, with—ah—power to increase its numbers.”68 Whether James ever did make this exact statement, or whether it was one of the many “tongue-in-cheek” comments attributed to James by Prairie satirist/journalist Bob Edwards, some did come to believe that marriage for James and Isabella was a partnership with a goal to increase its “numbers” in terms of family fortunes.69 Writing in the Calgary Herald in 2000, David Bly noted about James,

Everything he did seemed to advance his career and his fortune. He met Isabella Clarke [sic] Hardisty, daughter of the late William Lucas Hardisty, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s chief factor for the McKenzie [sic] district. Isabella embodied the Canadian West. She was born at Fort Resolution, an HBC post, and grew up under frontier conditions…Her mother was the daughter of a Metis woman.70

Certainly, James’s achievements in the world of politics and wealth accumulation speak to a man driven to succeed, and his marriage to Isabella contributed greatly to his ability to do that.

We cannot understand James’s success without examining Isabella’s contribution. As was often the case with unions made during and immediately after the fur trade, success in business depended on a productive partnership. Writing about Elizabeth Boyd McDougall, second wife of Methodist missionary John McDougall, MacEwan noted that, after their marriage, “from this point forward, the husband and wife story become so interwoven that it was difficult to relate about one without talking about the other.”71 For James, the items of exchange became land, money, and legal services; and Isabella’s entries in the marriage’s accounting books balanced with fur trade family connections, hostess skills, mothering skills, boosterism, and networking, all of which are difficult to measure but yet equally important to the couple’s success.72

There is no way to accurately measure the value of Isabella’s contribution to the partnership, or the degree to which she was involved in business decisions. However, from the time of his marriage in 1884, when he had modest land holdings, which included a small log house to which he brought his bride, to the time when the value of his property reached $75,000 in 1889,73 making him Calgary’s largest landowner, the transformation of James’s social position was quite impressive. At least one family member believes (while noting he has nothing against James) that Isabella deserves to be known “in her own right.” Great-grandson Robert Lougheed continues that James’s decision to marry Isabella was a “very good decision politically and economically for him…The marriage certainly helped his law and political career.”74

Even his legal partner noted the importance of Isabella’s family to James’s career. Among John A. Macdonald’s papers, there is a note from Peter McCarthy, at the time James’s law partner, in which McCarthy indicated he was “writing to encourage appt of JAL to Senate.” McCarthy noted a number of attributes in favour of James’s appointment, one of the first of which is not related to James’s skills but that “he is a relative by marriage to Sir Donald A. Smith and also to the late Senator [Hardisty].” He continues,

He is a personal friend of the Hon. Edgar Dewdney and along with myself has spent a considerable sum in sustaining the only Conservative organ in Alberta…he and I have within the last two weeks been forced to purchase the plant and franchises of the Calgary Herald to prevent it [going insolvent?].75

Certainly, the press noted that when James served in the Senate, Isabella was making a contribution to the advancement of her husband’s career, both in the North West and in Central Canada. Quoting from the Montreal Star, the Morning Albertan noted in 1912,

Quite a loss has been temporarily sustained by the official social set at the Capital by the return to Calgary of Mrs. James A. Lougheed, wife of the government leader in the Senate, who has been one of the most active and most popular official hostesses since the Borden Government came into power. Mrs. Lougheed is the mistress of one of the largest and most beautiful houses, not only in Calgary, but anywhere west of the great lakes, and it is but natural that she would desire to return to her western home as soon as her duties at Ottawa would allow.76

The article in the Montreal Star demonstrated the importance of Isabella’s fur trade family, when it deemed to provide an “outline of the patriotic services of a woman whose family for two generations has contributed to the development of the Canadian west.”77 As a way to demonstrate her success, the Star (as reprinted by the Morning Albertan) continued to educate Central Canadians about Isabella’s links to the development of the North West, writing,

Mrs. Lougheed, whose maiden name was Belle Christine Hardisty, was the daughter of Lady Strathcona’s brother, the late Mr. William L. Hardisty, who, in the middle of the past century, spent thirty eight years in the wilds of the Mackenzie river district, in the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company…Mr. Hardisty’s family spent many years in the wilds…She is an ideal hostess, full of honest fun and unassuming.78

The article continued that Isabella intended to “return to Ottawa next session,”79 a plan suggesting she understood it to be to James’s advantage that she attend Ottawa regularly when Parliament was in session. Prior to the hardening of public/private spheres in the later 1800s, elite women in British North America “could play powerful roles, making or breaking the political careers of their male relatives…or promoting the political goals of their choice.”80

Unfortunately, not much is known about Isabella’s public activities until the time of her husband’s political career, when her involvement in many organizations and activities became more newsworthy. However, if we are to judge by later reports in newspapers, both were always involved, as a couple, in community boosterism and building. In early prairie society, churches assumed major roles as institutions of boosterism and building, and James and Isabella were always committed members of Calgary’s Methodist Church.81 As well as his church activities, James was active as a school trustee and member of the Calgary Board of Trade.82

Many of James’s political duties would necessarily involve Isabella’s assistance, not only in Ottawa but in Calgary. One example was his work on the organizational committee for the Calgary reception of Sir John A. and Lady Macdonald in July of 1886, when they were on board the first passenger train across the country that was meant to promote the North West as an important part of the new Canada. No doubt, Isabella was present during that visit, when one of Lady Macdonald’s official functions included laying the cornerstone for Knox Presbyterian Church.83

Because so many of James’s responsibilities necessitated Isabella’s hostess skills, they needed to have a home that was suitable to host dignitaries. As noted earlier, it was not long after James’s appointment to the Senate that he and Isabella made plans to build Beaulieu House. Not unlike the forts of the HBC, Beaulieu became the temporary accommodations for many visitors to the North West. Some of these visitors included members of the British royal family. According to some observers, James and Isabella considered themselves to be aristocrats like those they entertained, “remaining aloof, enjoying public esteem if not public affection.”84 James was even said to sport a British accent, despite the fact that he was born in Toronto’s Cabbagetown, and that he spent most of his adult life in the North West.85 James was not alone in emulating aristocracy, for it is said that many in the ranching community “tried to represent the standards of an established landed gentry.”86

Some of his contemporaries mocked James’s apparent attempts at aristocracy. H.F. Gadsby, writing for the Canadian Liberal Monthly, kidded,

One of Senator Lougheed’s chief qualifications as Senate leader…is his rich, crusted old English Stilton accent…If any other citizen of Calgary than the one who collects rent from half the town said “ahftahnoon” instead of afternoon he would be dumped in the Bow River. But Senator Lougheed gets away with it…You don’t look for an English accent with a Scotch name like Lougheed…It probably grew up with the Senator when he went to Calgary to grow up with the country. There were many remittance men in Alberta at the time, and accent was about the only thing they had to give away.87

Still, some took the aristocratic persona seriously. In 1921, when the Toronto Star Weekly described the Senator’s presence in chambers, it noted,

You would say that he was an English visitor, probably an army officer, or a hunter of big game…You will be surprised to learn that…the man you took for an English visitor has lived all his life in Canada.88

He may have begun a humble existence in Cabbagetown; however, after his marriage to Isabella, James was frequenting places such as the Roxborough Apartments, where he stayed while in Ottawa. The Roxborough, where many of the politicians and business elites stayed, was built in 1910 by Boer War veteran Colonel James Wood, and featured architecture that successfully portrayed “an air of British solidarity and respectability.”89

Aristocrat or not, James was sufficiently influenced by Isabella’s very social nature so that he shed aspects of the strict Methodist requirements of his early Sunday schools, such as that which forbid dancing.90 Although both James and Isabella hosted dances at Beaulieu, it was Isabella who was exposed to the arts at Miss Davis’s school and at Wesleyan Ladies’ College, and it was likely her influence that led James to invest in the Calgary arts scene throughout his life. In addition to Isabella’s very social nature, no doubt, the world of nineteenth-century politics, with the “noise, the whiskey, the laughter, the tobacco,”91 not to mention the patronage and scandals that often accompanied it, also had a somewhat relaxing effect on James’s strict upbringing.92

Despite some softening, James never strayed from the attention to self-improvement that was inspired by his strictly religious mother. He carried on with many of the activities from his youth, such as helping to organize a Literary and Debating Society in Calgary in 1882, with fellow lawyer Paddy Nolan.93 It appears that 1882 was a “landmark” year for the arts in Calgary, when Nolan was also involved in organizing the Calgary Amateur Dramatics Association.94 In fact, James and Isabella were always on the forefront of philanthropic organizations in Calgary. As one historian notes,

Calgary’s business leaders were usually too busy to cultivate a lifestyle markedly different from that of their employees. Thus, social leadership generally came from churchmen, senior government officials and members of the professions. However, some individuals, like James A. Lougheed…were prominent in both business and social reform.95

A committed church member and government official, James fits the normal criteria of such early social reformers, and, as his wife, Isabella assumed some of that responsibility for social reform.

As a politically active and socially conscious couple, James and Isabella were the focus of much media attention, and also the consistent subjects of commentary by the popular Prairie satirist, Bob Edwards. During the twenty years of publication of his paper, the Calgary Eye Opener, Edwards used humour to draw attention not only to the Lougheeds and their contemporaries but to the social injustices of his times. As historian Sarah Carter wrote, Edwards made “merciless fun of the fox-hunting and pheasant-shooting society, class distinctions, privilege and aristocracy.”96 In July 1906, when rumour had it that Lougheed would be knighted, meaning that Isabella would also earn the title “Lady,” Edwards commented,

A knighthood is the infallible stamp of mediocrity nowadays, a sop thrown by royalty to pretentious four-flushers. Our beknighted senator will interject more “ohs” and “ahs” into his conversation than ever after he is Sir James.97

Edwards chided the opportunism of the Lougheeds, noting that, when James threw his support behind a new civic centre and post office, to be located at the “foot of First street west,” this would conveniently mean “a street car line down past the Sherman Grand and the new vaudeville house which the senator contemplates erecting shortly.”98

Whatever Edwards really thought of the Lougheeds, James and Isabella were clearly adept at political manoeuvring. In 1911, the first Conservative government was elected after a long hiatus in opposition that began in 1896. Soon after that election, James was appointed a member of Robert Borden’s Cabinet, as Minister without Portfolio. Then in 1915, James was appointed acting Minister of Militia and Defence, a key wartime responsibility. In July 1915, James became chair of the Military Hospitals Commission, a position he held under the Union government until 1918.99 It was a position that likely became more personal when James and Isabella’s son Clarence enlisted in 1915 for active service as a major with the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force,100 and again in 1916 when Edgar enlisted as a lieutenant. It was reportedly for his service during the war that James was knighted on 3 June 1916.101

In addition to the importance of being granted the titles “Sir” and “Lady,” in honour of James and Isabella’s positions in the new social fabric of the West, their names were eventually bestowed upon everything from remote islands to mountains. Perhaps the most fitting tribute, though, might be that which demonstrates the importance of the linking of the Lougheed family to that of the fur trading Hardisty family. In 1906, a small central Alberta town, situated on Highway 13, ten kilometres southeast of Sedgewick, assumed the name “Lougheed” in honour of Senator and Lady Lougheed. The CPR station directly to the east of this small prairie town, at the crossing of the Battle River in former Metis buffalo-hunting territory, held the name “Hardisty,” in honour of Isabella’s fur trade family.102

Perhaps the Calgary Herald stated it most appropriately in December of 2001, when it wrote, “Underpinning all of Sir James Lougheed’s achievements is the fact that he married well. Isabella Clarke [sic] Hardisty was truly a daughter of the Canadian West.” As the article continued, “With her connections, she could probably have done well in Toronto, Winnipeg or Montreal, but after her father died, she chose to live with her uncle in a muddy hamlet called Calgary.”103 As marriage and business partners, James and Isabella very soon witnessed this muddy hamlet transform into a showcase of boosterism for the new West, and they were themselves catapulted into the positions of Sir James and Lady Isabella.

The quotation in the Calgary Herald in 2001 demonstrates that James (more so) and Isabella have continued to be recognized as important community builders. However, even during their own time, many Calgarians felt they knew Isabella and James well. One of those, William Pearce, “one of Calgary’s oldest residents (who) has known Sir James longer probably than any other person in this city,” described James as “always very industrious and aggressive.”104 Yet, even when the political climate in the North West had changed drastically, James’s contemporaries recognized the wisdom of his choice for a wife in the daughter of fur trade aristocracy. In fact, far removed from the North West, James’s fortuitous marriage arrangement was recognized. An article in the Toronto Star Weekly in 1917 noted that, among his

Many Wise Moves…Two years after he left his home in Toronto he was wise enough to take a wife unto himself in the person of a Miss Hardisty, whose father was a Hudson Bay factor and uncle a member of the Dominion Senate…Five years after this happy event came his real entry in public life, when, on the death of Senator Hardisty, through an accident of a runaway, he was the choice of the Government as his successor…In the Senate the Hon. James Lougheed may not have proved himself to be amongst its most brilliant members, but he has certainly been one of its ablest.105

Perhaps he was not among the most brilliant members of the Senate, and it was true that he had married well, but it is also true that James was politically astute and knew how to invest wisely. According to historians Donald B. Smith and David Hall, authors of James’s online biography, the senator was a great supporter of business interests, and at one point he brought forward legislation that would limit the rights of workers.

Likely due in part to his business interests, James appeared to show little regard not only for the worker but for Isabella’s ancestry. For example, according to Smith and Hall, James

shared common western conservative views about Canada’s Native peoples. Canada, in his opinion, had by far the best record of any country of dealing with its indigenous peoples. He firmly believed that the First Nations required a strong paternal supervision by government. They must not be allowed to impede progress. While in opposition he had wanted the government to take power to sell Indian lands, especially when they were located close to settlements…In 1914 he strongly supported a government measure to do just that. In 1920 he vigorously advocated a bill to give government increased authority to forcibly educate and enfranchise natives.106

James did say, “The Indian has not those characteristics which make it proper to leave to his discretion whether he shall assume responsibility or not.” Two years after making this comment, James strenuously opposed as a retrograde and reactionary step “a measure to leave to the individual native the decision concerning enfranchisement.”107 Smith and Hall judged James’s opinion of First Nation people to be negative and paternalistic, referring specifically to a debate about a bill addressing game preservation in 1894. During the debate, James stated, “The Indians in my section of the country kill indiscriminately in the close season…The most destructive element we have in that country is the Indians themselves.”108

Whatever his sympathies, James may have been a more complicated man than many historians have acknowledged. In his role as a lawyer, James defended a range of clients, from women charged with being “keepers of houses of ill-fame”109 in 1889, to “Dr. Lovingheart” (aka Andrew Campbell) in 1893, when he was accused of performing an abortion for a Mrs. Maggie Stevenson.110 Charges were eventually dropped against Campbell, but he again came to the attention of police for failing to comply with the fire limit bylaw on his frame building.111 Given James’s conservative nature and that he was primarily a business lawyer, and that abortion was increasingly condemned in the nineteenth century,112 he clearly saw his practice in pragmatic terms and defined his responsibilities generously.

An article that appeared in the 19 March 1903 edition of the Medicine Hat News, and again on 26 March 1903, might have potentially harmed James’s reputation. The headline read,

King vs Lougheed: Defendant was charged with seduction under promise of marriage. On the application of the Crown, the hearing was postponed to secure necessary evidence. C.R. Mitchell for Crown. P.J. Nolan and D.G. White for accused.113

The story was also reprinted in the 23 March 1903 edition of the Calgary Herald, with a note that Chief Justice Sifton would preside shortly over the case at the Supreme Court in Medicine Hat. Again, few details were provided, other than that “King vs Lougheed Defendant was charged with seduction under promise of marriage.”114 Two months later, the Medicine Hat News, under the headline “The King vs Jas. A. Lougheed” reported,

The accused was charged with seduction under promise of marriage, and resulted in a conviction. On the application of the Counsel for accused the Chief Justice reserved the case for the opinion of the Poll Court. C.R. Mitchell for Crown. P.J. Nolan and D.G. White for the Defence.115

While it turns out that the Jas. A. Lougheed in question was twenty-three years of age,116 and thus could not have been Isabella’s husband, the local press did not appear to make the distinction.

Nonetheless, the reported conviction of a man bearing the same name appears to have had little effect on James’s career, as his pragmatism, his political influence, and his law practice continued to grow. Yet it was his junior partner, R.B. Bennett, who achieved his lifelong dream of becoming prime minister, even though James may have had that same dream. If James did have any such aspirations, as some news reports suggested, they went unfulfilled. One report claims that James “was passed over for Arthur Meighen, it is said, because his wife’s half-Native ancestry was too exotic for the Tory hierarchy.”117 Brian Brennan, reporting for the Calgary Herald in 1997, appears to have relied to a great extent on an interview with Donald Lougheed, James and Isabella’s grandson, when he indicated that family members generally agreed that James wanted to become prime minister, and they even believed that Isabella had been referred to as an “Indian wife.” Brennan wrote,

Due to the integrated nature of frontier society at the time, most found nothing unusual in what was nevertheless considered an interracial marriage because Belle was one-quarter Metis. But later, as James Lougheed’s position grew, he had to face taunts about his “Indian” wife. If it bothered him, he never let it show. Belle was hailed as “first hostess of the West” as she contributed to her husband’s career.118

Whether there were concerns about his wife’s ancestry, James’s marriage strategy was likely the most prudent, even if it did eliminate him from the competition to lead the national government. Certainly, James chose the politically expedient path of accepting executive appointment to the Senate and a wartime appointment as Minister without Portfolio, rather than seeking election. James may have learned political expediency from his wife’s uncle, Donald A. Smith (Lord Stathcona). It has been suggested that Lord Strathcona, married to the Indigenous Isabella Hardisty Smith, turned down an offer of a second peerage for fear of scorn over his own country marriage. So fearful was Smith of the gossip about his marriage as attitudes toward interracial marriages hardened that he arranged a private and “proper” European ceremony in New York when he and his wife were in their seventies.119

It is not clear whether his wife’s ancestry was ever a matter of concern for James Lougheed. However, as noted earlier, he certainly seemed to pay Indigenous people little regard when the matter of their rights might interfere with business interests. In 1906, during debate in the Senate chambers, James again defended business interests over Indigenous rights, arguing that the government ought to be

taking to itself larger power to dispose of many Indian reserves contiguous to settlement, rendering it undesirable that the Indian should be there in the first place, and in the second place that the lands should be held from settlement…That, I might say, is becoming a matter of considerable importance to growing centres in the new provinces. Very large tracts of land are tied up immediately adjoining important centres of civilization and settlement, and it is both prejudicial to the Indians and prejudicial to settlement.120

Immediately after James’s argument that favoured settlement by newcomers over treaty rights, the Senate adopted Bill 194, which amended the Indian Act.121 In 1911, James supported another motion to amend the Indian Act by way of Bill 177, in which it was deemed “a good thing for Indians to be moved from the vicinity of towns where they are exposed to vice drunkenness and immorality.” This was also the amendment that made reserve land available for annexation and purchase.122 In 1920, James defended the British Columbia Indian Lands Bill, arguing, “No other Indians have been as well looked after as the Indians of Canada.”123 He continued that British Columbia had “looked after the Indians with a parental attention.” James further stated that the federal government was at no fault either, for “the treatment of the Indians by the Government of Canada has been proverbial for sympathy, for generosity, and for all that parental solicitude could do for any section of the population.”124 Later in the debates, James continued, “The Indian has not those characteristics which make it proper to leave to his discretion, whether he shall assume responsibility (i.e., accept franchise) or not.”125

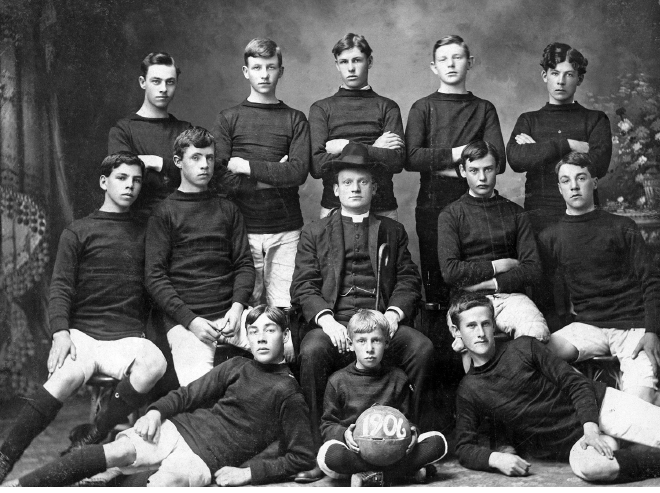

Western Canada College football team, Calgary, Alberta. Front row (L–R) : Norman Lougheed, C. Smith (mascot), —. Centre row (L–R) : R. Oakley, H. McInnes (captain), Dr. Archibald Oswald MacRae, A. Thomas, G.E.H. Johnston. Back row (L–R) : Ronald Freeman, W.J. Sharpe, M. Jaffray, H. White, W. Simpson. Photo dated 1906.

Glenbow Alberta Museum and Archives, NA-3899-2.

In this regard, James held the same views as those of Dr. Archibald Oswald MacRae, the principal of Calgary’s Western Canada College, the very school James and Isabella’s son Norman attended. According to MacRae, “The Red Man of the West has always been a difficult individual, he does not care to work, to beg he is not ashamed. In consequence he tends to become shiftless and vagrant.”126 It is reasonable to assume that both James and Isabella were aware of Dr. MacRae’s views.

Given James’s own expressed views of Indigenous people, it should be no surprise that Indigenous activist Fred Loft’s appeals to James while he was Minister in Charge of Indian Affairs, so well-articulated, were all for nought.127 Later, when the Conservatives were out of power and the Liberals brought forward amendments to the Indian Act, effectively doing away with forced enfranchisement, Lougheed defended his party’s policies, saying,

It seems to me that the law of 1920, which we are not altogether repealing, but which we are weakening, was a very salutary statute. The policy of that law was that the Government, of whom the Indians are the wards, would determine whether an Indian should be enfranchised…Upon every reserve there are always a certain number of restless and dissatisfied spirits who will attempt to make trouble…They want to continue in the position of wards of the nation…if we give recognition to that spirit of dependence on the Government, we shall never be able to develop our administration of Indian affairs to that stage at which we shall finally solve the Indian problems of Canada.128

Clearly paternalistic in some of his political views, which might suggest the same in terms of parenting style for James, there is evidence that Isabella had a somewhat more relaxed parenting style.129 There was one very public example of the differing views on parenting that might have been embarrassing for James’s political career had he been an elected official. This example occurred shortly after James had departed for Ottawa on one of his frequent trips. Despite a warning from James that Isabella and their sons should not undertake such a trip, James had no sooner left than his family took the automobile for a road trip to Banff. According to the Banff Crag & Canyon, Norman Lougheed had arrived in his “big automobile, this being the first car to enter the National Park over the coach road.”130 Indeed, the Lougheeds had undertaken their road trip at a time when vehicles were prohibited inside the park, thus their vehicle was promptly seized.131

Years later, Mary Stringer Lougheed, who had been along on the joyride, recalled the “hectic venture of driving through swamp, rut, and bog to get to Banff.” She confirmed the trip went ahead despite the fact the senator had “put his foot down calling it foolhardy! ‘The impulse of a bunch of kids and poor old granny!’” Mary noted that, after James left, the boys and Isabella immediately got busy. The car was made ready with an extra can of fuel, the tires inflated with hand pumps, and the family cook put up a “huge hamper of food, for of course there were no restaurants on the way.” Mary recalled that things

breeze [sic] along wonderfully for the first ten miles. We had our hats tied on with a mile of veil. Norman wore big gauntlets and a driving cap with goggles. The motor veils streamed behind in the wind. It was wonderful: a lovely sight as we approached the Rockies.132

Along with two other vehicles, the motorcade “roared by at 15 miles per hour to follow the old Indian and wagon trail west.” When the two other cars lost steam, the Lougheed car “roared on alone.” Dealing with eight-inch ruts and bears, the car slowed to three miles per hour, when “in front loomed an Indian wagon loaded with small fry in the back.” Despite the challenges, Isabella and her sons made it to the village of Banff, where

soon eager citizens crowded round and offered congratulations. The triumph of being the first car, however, was short lived…An RCMP officer on a horse came along with a summons. The stunned Calgarians saw their car impounded. It was wheeled into Brewster’s livery stable and locked up.133

Not deterred by the impounding of their car, and apparently not in the least bit concerned about any political implications for her husband, Isabella and her sons

took in some of the loveliest scenery in the world on horseback. They drifted in gaily painted canoes across lakes and down picturesque rivers. They rode through pine forest, beside swift mountain streams.134

Apparently, there was some leniency granted for whatever reason because, after their time enjoying the scenery, “the authorities said they could have their car back if they went directly out of town.”135

All might have gone unnoticed by the senator, hard at work in Ottawa, had a tire not blown near Kananaskis on the way back to Calgary, when the car “veered to the right, ran off the road down a slope, and smacked into a tree.”136 After the mishap with the tire, according to Mary Stringer Lougheed, “Granny” (Isabella) showed her “pioneer heritage” by walking back the seven miles to the tiny station on the rail line. According to daughter-in-law Mary, though suffering swollen feet, Granny “surprised everyone with a tremendous show of energy,” making it to the station, where they boarded a train back for Calgary.137 According to the same article in Golden West Magazine, to which Mary granted the interview in 1977, “The Hardistys had battled the frontier for generations so Lady Belle was in her environment.”138 At least one researcher, who spent time reading between the lines of correspondence about Isabella, observed she had a “wild” side that eschewed the restraints placed upon her by the rigours of public life as a gracious woman in the new West.139

Reportedly, Lady Lougheed commented with some pleasure after the trip that “we looked like a bunch of tramps.” A few days later, a train crew dragged the stranded auto onto a flatcar, leaving it on a sideline beside the main track in Calgary. Suspecting nothing, James returned home from Ottawa on the train, when, upon his approach to Calgary, he “looked out the window he could hardly believe his eyes. There, on the sideline, looking lonely and forlorn, was his prized Pope-Toledo, battered and bent!” The senator arrived home to find a “rather chastened family admitting that they had disobeyed his wishes and ended up a crocker.” However, “Lady Belle soothed things down and finally the whole thing ended up with a big laugh.”140 It appears that the patriarchal attitude James displayed publicly was, at least on this occasion, shed at the doors of Beaulieu.141

Commenting on the difference in world view between James and Isabella, Lougheed House researcher Jennifer Bobrovitz wondered if Isabella’s background as a child of the fur trade might have contributed to her desire to push the boundaries of protocol in the new North West.142 Regardless of what contributed to it, pushing boundaries no doubt contributed to Isabella’s reputation as one of the most successful and fun hostesses of the new North West.

Isabella may have had a desire to push the social boundaries, but she did work as a team with James toward realizing the goal of boosting family fortunes. Together, James and Isabella were involved in the early stages of most social initiatives and community organizations in Calgary. However, there were some clubs the couple could not join together, such as the elite Ranchmen’s Club, fashioned after the British gentlemens’ clubs that originated in the 1600s. For a long time Calgary’s club forbade the membership of women.143 Even though Isabella could not join the club, in February 1914, son Clarence joined James when he was also elected as a member.144

Although she could not join all of the same clubs as James, Isabella took her role as first lady of the transitional society seriously. One of the duties she assumed was that of greeting newcomers to Calgary. As Christian Helen Drever, one of the Drever sisters from St. John’s Parish in Red River, related, when she arrived in Calgary on the train in 1886, Isabella was her first visitor.145 Christian married J.P.J. Jephson, “pioneer barrister,” while her sisters also married Calgary pioneers and community builders, one the Anglican bishop, Cyprian Pinkham, and the other, Colonel James Macleod.146 The Drever women would join Isabella in many of her philanthropic endeavours. While Isabella made it a habit to welcome new arrivals, there is a good possibility she knew of the Drever girls already, given their attendance at Miss Davis’s school in Red River.

Indeed, newspaper reports confirm an extensive social schedule for Isabella, and there are a few private details that also confirm this busy schedule. During the restoration work at Lougheed House in the 1990s, one of Isabella’s dance cards was found behind the baseboard. Although the card appears to have been used later by a child to scribble on, there is a name filled in next to all twenty of the dances listed on the program, suggesting Isabella may have been on the dance floor the entire evening.147 When the Calgary Daily Herald reported that Isabella was to attend the state ball in Ottawa, it made sure to mention she had been “asked to dance in the state quadrille.”148

No doubt, it was a great pleasure for the fun-loving Isabella when, in October 1912, a young Fred Astaire and his sister Adele introduced the tango to Calgary during a vaudeville act at the Lougheed’s Grand Theatre.149 Despite concerns expressed by local clergy150 and the officials from the local university’s administration, who forbade students to take part in the tango, it was rumoured that Isabella had organized a “dansant” at Beaulieu for her daughter Dorothy on 1 January 1914, where guests reportedly partook in the tango.151

Clearly, Isabella, who likely did host the “dansant” for Dorothy and her friends, enjoyed playfully teasing the media. While many minute details were confirmed, such as the choice of “large yellow mums and yellow and white tulips…tea was served at 4 o’clock,” as far as the tango, the Albertan was forced to conclude, “whether or not the tango was danced the young people had a merry time and are looking forward to another similar event this afternoon.”152 It appears that Isabella continued to host many “dansant” at Beaulieu, despite warnings such as that given by Rev. C.C. McLaurin in 1915, during an address to a Baptist convention, where he described the West as “dance crazy,” and cautioned that “such worldliness and pleasure-seeking” were a “curse to the community.”153 Isabella’s networking skills must have been exemplary, for there is no evidence that her reputation suffered, even though she enjoyed activities deemed a “curse” by some community leaders.

While William Hardisty had expressed concerns about Wesleyan, and it appears Isabella was lonely there, it seems she did enjoy at least some aspects of her education, which served her well as a young married woman. Clearly, she was able to apply the skills she learned at Wesleyan to enriching the social fabric of Calgary. By all accounts, Isabella was an accomplished pianist and certainly supported all aspects of Euro-North American cultural activities in Calgary throughout her life. It was no doubt her interest in the arts, garnered at Wesleyan, that inspired Isabella to establish the Grand Theatre with James in Calgary and to entertain world-renowned performers, such as Kathleen Parlow.154

Equally adept at official functions as she was at entertainment, Isabella attended the ceremonial laying of the cornerstone for Alberta’s legislative building in Edmonton in 1909, perhaps fittingly on the site of the former home of her uncle, Chief Factor Richard Hardisty.155 Press coverage of the event noted that the former HBC post, which overlooked the North Saskatchewan River, was perhaps one of the “most important trading posts of the Hudson’s Bay Company in the then North American wilds.”156 One official commented about the continuation of HBC tradition and the importance of the site for the transition of the new West, saying,

we are after all only aiming to establish for our people the most important and imposing structure in the province upon a site, in our judgement, well suited for the purpose, and in doing so following in the footsteps of the officers of the historic trading company who established themselves upon the same ground some two generations before.157

Like her uncle, Chief Factor Richard Hardisty, all indications are that Isabella came to be regarded as an important public figure. Before her attendance at the Alberta Legislature, “Mrs. Senator Lougheed” had stood in for her uncle, Lord Strathcona, when the cornerstone of the new Methodist Church was laid on 12 May 1904 on the corner of what is now 7th Avenue and 1st Street East in Calgary. After a telegram was read from Lord Strathcona, “Mrs. Lougheed stepped forward and ‘with trowel in hand declared the stone well and truly laid.’”158 Isabella performed this function despite the fact that Senator Lougheed was also present. While it would not have been unusual for women of some standing to perform official functions, James was the one with the official designation, not Isabella.

In part due to her marriage to the new senator and in part due to her membership in the Hardisty family, Isabella’s activities came to be closely monitored by the local press. While there was a good deal of attention devoted to her philanthropic activities, readers seemed just as interested in her private life. One such example was the 1907 report in the Calgary Daily News, which advised readers that Isabella and a Mrs. Grott were to holiday in Laggan.159 In September 1908, the Calgary Daily Herald informed readers that Isabella was “At Home” for the first time since the renovations at Beaulieu, commenting that the dining room had been enlarged and redecorated, while the “roses are grown with wonderful success in the rosary opening off the dining room.”160

In typical booster fashion, newspapers referred to the “delightful tea hour reception” hosted by Isabella in honour of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, followed by an evening dinner at the Ranchmen’s Club, where James proposed the toast to the king.161 Reports were always peppered with tremendous detail, such as the description of the grounds at Beaulieu during the prince’s visit:

Masses of vivid flowers against the borders of green trees and foliage were an effective background for pretty light-colored summer frocks worn by the women…the reception was therefore a very informal and intimate tea party, permitting of pleasant chats with the prince and the members of his entourage. By a coincidence, it was for the most part a gathering of “old-timers” of the city—a majority of the guests having been contemporaries of Sir James and Lady Lougheed in this city for the past fifteen or twenty years.162

Not only does this excerpt confirm Isabella’s hostess abilities (and her position as an old-timer) but it also speaks to her astuteness in contributing with a magnificent garden to the “City Beautiful” movement that swept North America in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

In addition, it surely was no “coincidence” that the majority who were invited to greet the prince were fellow “old-timers,” referred to as “contemporaries of Sir James and Lady Lougheed.” It was also likely no coincidence that the entire Lougheed family was on hand to greet the prince. This included young Dorothy, dressed in a “very effective gown of black with a smartly-draped tunic heavily brocaded with gold,” along with Captain Edgar Lougheed and brother Douglas.163 Bobrovitz muses that James and Isabella may have sought to extend their kinship network to include British royalty by manipulating situations that might inspire the dashing young prince to take a shining to Dorothy.164

Local writer Jean Leslie also suggests that Isabella and James sought to boost the importance of their own family unit by encouraging a romance between their daughter Dorothy and Prince Edward. According to Leslie, “one evening…Edward, Prince of Wales, danced into the wee hours of the morning with Lougheed’s daughter Dorothy, who was an excellent dancer.”165 It is not clear if Dorothy joined Isabella when she later travelled to Banff, as did the prince, where Isabella attended the ball given there in his honour.166 Whether or not there was a desire to expand her family network to include the prince, Isabella’s connection to him certainly boosted her own social network, as did the fact that she lived in a house suitable to entertain royalty.

Given the fact that the Lougheeds lived in the “Big House,” it was only natural that their home would be the venue from which the new North West welcomed many visiting dignitaries. Given the importance of Beaulieu to promoting the West, Isabella assumed an important role in the marriage partnership, as she managed the social capital that was Beaulieu House. There are many examples found in the local newspapers, reporting Isabella’s superb “hostess” skills in particular. One such example was the occasion when Isabella and James hosted Nicholas Flood Davin, at which time Davin delivered a “most eloquent speech.” As well as commenting on the speech, the reporter noted,

A most enjoyable and instructive evening was wound up with a cordial vote of thanks, which called forth enthusiastic cheers to Senator and Mrs. Lougheed for the courtesy and hospitality shown by them to the members of the Liberal Conservative association.167

In fact, the Herald positively “gushed” in its 1 February 1900 edition, writing,

Beaulieu…was last night the scene of a brilliant society event, when the Senator and Mrs. Lougheed were “at home” to their wide circle of friends and acquaintances. Entertaining at Beaulieu is the synonym for all that is best and most hospitable in Calgary’s social history. Not even Government House at the territorial capital at its palmist could exceed Beaulieu as it appeared last night with its gay company of handsome women and their escorts. What less, indeed, could be expected? The appointments were in every respect perfect, the music bright and crisp, the supper unsurpassed, the dresses such as would have graced a London ballroom, and the host and hostess doing everything they could [to] conduct to the enjoyment of their numerous guests. Dancing began shortly after 9:30 to the music of Mons. Augade’s orchestra and was sustained with the utmost interest until an early hour. In the spacious billiard room, gentlemen who were no longer devotees of Terpischore enjoyed whist, billiards, cigars and mellow conversation. The spacious rooms, admirably designed for dancing, looked most brilliant in their floral decorations of pink and white carnations, white Roman hyacinths and palms.168

Readers could not help but be impressed by the transformation of former fur trade country into a space that now boasted venues equivalent to London ballrooms.

In another report speaking to Isabella’s skill as a hostess, the Calgary News Telegram confirmed that Isabella often relied on her children for assistance when she threw open her

magnificent home to the many charitable organizations of the city, and [its] spacious ballroom is thronged several times during the season with the many friends of her sons. In early January 1914 Belle held a Saturday afternoon dance jointly for her 15 year old daughter Dorothy and her 20-year old son Edgar and their friends in the Lougheed House tea room.169

With James away so often attending to Senate work in Ottawa, the social calendar, so crucial to successful business networking and boosterism in the early Prairie West, was left in Isabella’s capable hands.

Often, Isabella was accompanied in her leadership and hostess role by her son Clarence, and at times other dignitaries. For instance, when their Sherman Grand Theatre opened its doors in Calgary, Isabella had Clarence by her side. Later, it was Mrs. Arthur Sifton who joined Isabella.170 If James happened to be in Calgary, he stepped right into the events that were pre-arranged by Isabella, as evidenced by the report in the Albertan that “Senator Lougheed, who returned to town last night from Ottawa, was able to be present.” Despite James’s presence, the Albertan still noted that it was “Mrs. Lougheed who was entertaining a box party.”171 This description does not imply that James was irrelevant, for it was noted by one newspaper that he was “not an aggressive fire-eater, but, as an executive and as a diplomat, he has few equals at Ottawa.”172 These examples do suggest, however, that it was Isabella who directed much of the couple’s commitments and their role as social leaders in Calgary.

Isabella Lougheed (front row on the left) and James Lougheed (back row, third from left). Photo undated. Lougheed House National Historic Site Archives, LHCS 2-1.

In addition to opening Beaulieu to many social events, as a member of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE), Isabella often opened her home for causes such as that which saw 150 guests raise funds for the Boy Scouts. All indications in the local newspapers are that Isabella enjoyed a reputation as a fun-loving hostess, in whose home guests always had a “merry” time and were left in the “happiest mood.”173 While most gatherings in the homes of Calgary’s “upper” set were described as “delightful,” Isabella’s were most often described as “lively” events, where, for example, “Music and animated conversation were followed by several lively contested games of cards.”174

Often, the music enjoyed at the Lougheed mansion was provided by the woman known to service men and women as “Ma Trainor.” Josephine Trainor was actually a serious pianist,175 who, after playing at Beaulieu, once recalled, “A cheer went up after the first waltz and next thing I knew the Lougheed boys had talked their mother into hiring me for their next dansant.” Again speaking to the social events that Isabella organized, in 1914, the Calgary Herald reported that the “dansant” given by Isabella in honour of her daughter Dorothy proved to be “one of the smart and delightful events of the season.”176 Over seventy guests reportedly had such a “merry time” that they looked forward to another similar event very soon.177 Isabella also helped organize a winter club, to “encourage figure and fancy skating as well as other winter sport in Calgary.”178 At the fifth annual Pioneer Association Ball in 1913, Isabella and other guests enjoyed moose steak and the orchestra’s rendition of the “Red River Jig.”179

Equally at home with old-timers or royalty, the Lougheeds were always centre stage, even opening their home so the Duke and Duchess of Connaught could make it their residence. In fact, when in Calgary, the duke and duchess, “contrary to the usual custom…requested that their host and hostess should not leave their home during the royal sojourn.”180 This unusual request by Arthur, Duke of Connaught, son of Queen Victoria, was likely the result of the time he had spent with Isabella earlier in Ottawa. It was reported in March of 1912 that Isabella “was singled out for the distinction of the Duke’s company” at a dinner reception. Reportedly, at this dinner, “the conversation was turned almost immediately to western topics,”181 and was surely a wonderful opportunity for Isabella to share some of the successes of the new North West. Demonstrating the boosterism common at the time, during this September visit by the royals, the Calgary News Telegram noted,

Nowhere in the east can be found gardens that surpass those surrounding the Lougheed home…The sight of these gardens will put an end to that Eastern fallacy that it is impossible to grow flowers in the West.182

Isabella’s importance to boosterism of the West is evident in the 1913 Special Souvenir Issue of the Calgary paper, the Western Standard Illustrated Weekly. In this issue, the Calgary Women’s Press Club claimed,

The Last Best West is the women’s west. Nowhere else in the world is the evolution worked by the great feminist movement of the last century demonstrated more strikingly.183

The women of Calgary used the special issue to “call upon western men to be ‘fair and generous,’” and highlighted successful women who ran their own businesses and farms, or who held professional jobs. Despite the fact she did not operate her own business or hold a “professional” job, Isabella was featured in the article as one of these women of success. Although her ancestry was not mentioned, Isabella was listed as one of the few “western born women.”184