6

Queen of the Jughandle

WHILE MARIE ROSE eventually referred to herself as “Queen of the Jughandle,” she and Charlie began their married life “following the treaties,” a phrase Marie Rose wrote was used by the fur traders who “followed the Government agents into Indian territory, as they paid the treaty money to the Indians.” While she had an intimate knowledge of the Indigenous perspective of the treaty-making process, Marie Rose also understood the perspective of Charlie Smith, “the trader, and many others [who] followed the treaty from place to place.”1 According to Marie Rose, “The traders obtained money easily from the Indians at such times, for any merchandise they had to sell.”2

However, Marie Rose expressed her disapproval of Charlie’s business practices, writing, “It was regular robbery! One pound of tea, we traded for one buffalo hide; one pound of sugar for one skin…Charlie had more liquor than his permit called for.” Marie Rose, describing her early days with Charlie, recalled that after loading their democrats with merchandise, they “travelled closely behind the commissioner, who paid the Indians their treaty money. Then we traded for cash or skins, some of the provisions from our loaded wagon.”3 The fact that Marie Rose would refer to Charlie’s practices as “robbery” suggests he did amass what must have seemed like great wealth, as did many of the traders. Norbert Welsh noted that, although there were no more buffalo at this time, there were muskrat, wolf, lynx, bear, marten, weasel, badger, and prairie dog skins to be traded. Welsh recalled there were days that he took in five hundred dollars worth of fur, and that he doubled his money on every transaction.4 In Charlie’s case, his wealth was perhaps even more than Marie Rose had witnessed of her father’s trading, who had not had the opportunity to follow the treaties and did not take in cash. Whether one saw it as robbery as Marie Rose did, by the time he decided to stop following the treaties, Charlie had earned enough profit that he was able to go to Montana, where he “bought a herd of cattle with the treaty money.”5

As his newly purchased wife, Marie Rose had accompanied Charlie to Montana, where they lived on the treaty money during the winter of 1879. With his treaty wealth, Charlie was able to assemble a herd of “fine stock, the pick of the country.”6 The indication was always that Marie Rose and Charlie were in Montana gathering a herd for themselves only. However, Charlie declared in a scrip application for his son, Charlie Jr., in January of 1880, that he was in Montana in that year when his son was born, and that the purpose of this trip was to buy cattle for Governor Dewdney “for the Indian Department.”7 He could have been acquiring his own cattle as well as some for the government, and this could have been a second trip to Montana, given that Marie Rose and Charlie were married in 1877. Jock Carpenter wrote that Marie Rose’s mother and stepfather also made the trip to Montana in 1880 when 250 head of cattle were purchased and first brought to a chosen homestead near Fort Edmonton. However, in the spring of 1881, after a bitterly cold winter, Charlie moved the herd to the Pincher Creek area.8

Whatever return trip from Montana Marie Rose referred to, she appeared to enjoy the journey back onto the southern plains of Alberta with the herd, writing that it was a

wonderful life…all kinds of wild fowls, what more could any one wish. It was real life. Game was plentiful…the lakes and ponds were black with feathered game…The North West Territories was a sportsman’s paradise.9

Around the campfire at night, according to Marie Rose, Charlie related his “interesting adventures” travelling the plains when the buffalo were plentiful.10 No doubt these memories evoked pleasant conversations between the couple, as it was a lifestyle both had experienced.

While Marie Rose mentioned the many interesting adventures that Charlie had, in comparison to her writing about new settlers, she wrote very little about Charlie. Thus, for the most part, he remains a man of some mystery prior to his appearance in the North West, when he first set his sights on the sixteen-year-old French-Metis girl who had just left the convent. There are conflicting reports, both in a book written by his granddaughter, Jock Carpenter, and in official documents, about Charlie’s background. While the 1899 census listed his nationality as German,11 Marie Rose described him as a Norwegian who left home at the age of twelve for a life on the sea.12 Like Marie Rose, Carpenter said that Charlie, who sported fair, shoulder-length hair and blue eyes that “twinkled under scraggy brows,” spoke with the “unmistakable brand of the Norwegian.”13 At times Charlie was described as having a German accent,14 but was also referred to as “Dutch Charlie.”15 His obituary declared he was born on the Mediterranean Sea, and he reportedly once even claimed he was Spanish.16 The 1880 census of Missoula, Montana, where Marie Rose and Charlie gathered their herd, noted Charlie was born in Greece.17 There are handwritten notes in granddaughter Shirley-Mae McCargar’s Bible that suggest Charlie was born in Hammerfest, Norway, to Anna Peterson and Maeroward Smith. Notes further down in the Bible indicate Charlie was born “on Coast of Mediterranean.”18 In short, no one knew with absolute certainty where in Europe, or in North America, Charlie had originated, but we do know his home in Pincher Creek was a place where “no stranger was ever turned away without a good meal, as Charlie’s hospitality was well known.”19

The original homestead Marie Rose and Charlie had staked and named Jughandle Ranch was located on the southwest quarter of section 2, township 6, range 1, west of the 5th meridian of what is now the Municipal District of Pincher Creek, Alberta.20 On this homestead the couple built their first home, which consisted of the one-room log cabin with mud floors, and was attached to the barn. Marie Rose’s first years of married life with Charlie were anything but dull, and Charlie was certainly not committed to presenting himself to the new community of settlers as one of the elites.

For a large part of Marie Rose and Charlie’s early lives together in the new North West, there were no saloons, which meant that drinking took place in people’s homes. At times, families were given permits that allowed them to purchase Jamaica Ginger from the local drugstore. However, at Charlie’s house, permit or not, there were often “barrels of beer, a few bottles of Scotch and some Montana Bourbon Whiskey.”21 As Marie Rose wrote,

In those days men were boss and women had to obey, right or wrong. I obeyed to keep peace in the family. I did not like my husband drinking but I had to put up with it…I did the cooking and the work…My married life was full of trials and tribulations.22

Although her neighbour Ben Montgomery transcribed a version of this same sentiment, in her own words, Marie Rose wrote that child care was not made any easier by the constant revellers in her home:

The only time I could properly feed my children was when all were asleep. I then prepared a big meal, fed them and let them sleep, too. Many, many nights, I sat on the end of my long cot, with the children lying crosswise of the bed, packed together like little sardines, watching for fear the boys might upset the lamps and burn my little ones to death, or in their stupidity wander to the bed and fall upon it and crush one that might be sleeping.23

She admitted she sometimes got “real angry,” but to no avail, since “Charlie was boss.”24 Although she acknowledged that in her own marriage she faced many frustrations, Marie Rose still denounced “Indian” husbands as a general rule. As a way to demonstrate the superiority of marrying a Euro-North American man, despite all of his faults, Marie Rose wrote,

The Indian didn’t always make a good husband. Chee-pay-tha-qua-ka-soon (blue flash of lightning), who was once married to a young buck and reared eight children from this marriage said, “Indian husband no good, lazy. He beat me, see,” as she showed us the marks of punishment on her head.25

Marie Rose continued her account of Blue Flash of Lightning, “Later she married a white man and of him praised, ‘White husband, good; his squaw, a lady!’”26

Despite her aversion to alcohol, which may have originated with her time in the convent, or simply because of the impact Charlie’s drinking had on her family, Marie Rose openly described Charlie’s “business practices.” She wrote that he often had “more liquor than his permit called for. It was carried in small oak barrels of two gallon size.” She remarked that, on one occasion,

police were stationed near by [sic] and when any trader arrived they searched his carts. When the police came to us, Charlie put the kegs in two large pails and said, “Go ahead and search the carts while I go for water, and I’ll give you a drink of whiskey when I come back.”27

According to Marie Rose,

While the police searched, Charlie buried his kegs in the water and brought back buckets of water and treated the police from the store of whiskey, to which he was entitled by his permit.28

Marie Rose became well versed on the techniques of the bootleggers, no doubt in part because her husband operated as one. As she wrote,

Some of these smugglers had a dugout near Pincher Creek. Here they diluted their liquor with a mixture of black tea, ginger, and a little red pepper. It was a profitable undertaking for them, but fraught with much danger.29

There were a few published references to Charlie by others that offer more insight into his character and activities. These print references were made in regard to Charlie’s partnership with prairie character, Addison McPherson. Although Marie Rose does not mention the family connection, Charlie’s partner was a member of her Metis fur trade family. McPherson’s wife was Marie Rose’s cousin, Melanie McGillis, who was born at Saint François Xavier, on 18 August 1857, to Cuthbert McGillis and Marguerite Delorme, also known as Marguerite dit Hénault.30 Not unlike Marie Rose, Melanie McGillis was enrolled in the Grey Nuns School in Saint Boniface, however not by her parents. In Melanie’s case, it was her husband who enrolled her.31 By 1901, Addison and Melanie McPherson had moved further south to the Black Diamond area, where Addison operated a coal mine.32 It may have been Melanie McGillis, referred to as “Mrs. McGillis,” who accompanied Marie Rose on the trip to Winnipeg when she set out in the summer of 1882. On this trip, Marie Rose had hoped to meet up with Charlie, who had left some months earlier with the goal of taking advantage of a real estate boom in Winnipeg.33

When Charlie ventured out, either for wolfing or for some other activity, it could be for months at a time. During one of their wolfing expeditions, Addisson and Charlie “put up a cabin” in the Big Valley area. This suggests that the two would spend the winter there, setting up “hundreds of poison baits…already visioning a big harvest of skins.” Waiting for the spring thaw and the bounty of dead wolves ready for skinning, Addison and Charlie reportedly “settled down to feast on the abundant game, smoke, play cards, darn socks, try to out-lie each other in tall stories and live the ‘life of Riley’ generally.”34

During a poker game with Addison at their winter camp, Charlie was reportedly stabbed in the shoulder. Marie Rose mentioned the “crippled arm”35 that presented mobility problems for Charlie later. However, she did not describe the specific incident. She only wrote of the scars left behind from Charlie’s adventures: “Trading with the Indians oft times at the risk of losing his own life, the marks of such knives he carried to his grave.”36 No doubt the “crippled arm” of her much older husband forced Marie Rose to rely not only on her own abilities for survival but also on her kinship network.37

There are other references to Charlie that speak to the fact he not only carried on a nomadic lifestyle but was likely able to amass a fair bit of wealth at times, through fair or foul means. One reference to Charlie is found in the work of early local historian Edwin L. Meeres, who published one of the first local histories of the central Alberta district. He wrote of Addison McPherson and Charlie Smith’s involvement in many ventures, anything that could supplement their reported love of money and nomadic lifestyles. From trading in pelts and whiskey, to hauling mail between southern Alberta and Montana, to freighting from the Red River to the Rockies, McPherson is remembered not only for his humorous antics but for his ability to succeed in the new economy.38

According to Elizabeth Bailey Price, McPherson told her that he first came to the North West in 1869 in search of gold. Although he did not find gold, reportedly, one winter McPherson “traded merchandise for some seven to eight thousand buffalo skins.” He also related,

We took the trail to Whoop Up, then north to the Nose Hill, near the present site of Calgary, on the forks of the Red Deer River, then to Rocky Mountain House…From there, there was a good trail to Ft. Edmonton. In our gang, was the late Charlie Smith of Pincher Creek.39

In addition to ranching, these stories of trading upwards to eight thousand buffalo skins lend more credence to the argument that Marie Rose and Charlie were considered wealthy for some part of their lives, at least in comparison to some of Marie Rose’s Delorme family. There is a suggestion that Charlie’s wealth was gained not only through trading and ranching. In one interview conducted with Charlie in the early 1900s, he indicated that Marie Rose had inherited $10,000.40 If there was some inheritance, it likely came at the right moment, because freighting using the methods relied on by Charlie and Addison had come to an end. After the end of freighting between the Red River and the rest of the North-West Territories, Addison McPherson settled to a life of sheep ranching in the central Alberta area, and Charlie to part-time cattle ranching in southern Alberta.

During those times when Charlie was at Jughandle Ranch, it appears all were welcomed to his home. Marie Rose wrote often that, no matter who arrived at their doorstep, Charlie would tell her to put the potatoes on while he went for some fish. In fact, in the only audio recording of Marie Rose, produced a short time before her death, she still recalled this request by Charlie to “put on some potatoes.” Although many of the visitors to the ranch were no doubt Indigenous, Marie Rose made only brief references to these ongoing relationships. In one example, she wrote, “in groups of twenty or more” they would appear at her doorstep, and Charlie would say, “Mary, feed the poor Indians.” She explained that this is how she came by her buckskin:

Thus it was that I bought my buckskin from them, and I will tell you how I started to make buckskin gloves…I ripped the glove, cut a pattern from it and made my first pair of buckskin gloves, stitching them by hand. Then I branched out making buckskin shirts and bedroom slippers, drawing my own beaded designs.41

Whether out of appreciation for her beaded designs or because he recognized an economic opportunity, Charlie encouraged Marie Rose:

When my husband saw how interested I had become in the buckskin work, he gave me a wonderful surprise. On one of his semi-annual trips to Fort Macleod for supplies, he returned at the end of the two weeks and brought me—yes—a brand new sewing machine.42

Their continuing contact with Indigenous people likely led to little appreciation from both Charlie and Marie Rose of the panic that seized some new settlers during the fighting in Batoche in 1885. That year, when Charlie was called upon to protect the North West from anybody who took up arms along with the Metis, fellow volunteers in the Rocky Mountain Rangers reported,

A Dutchman by the name of Charlie Smith was our Lieutenant. Charlie would give the order—“Mount, Walk, Trot,” then when we got in front of the little log saloon—“Halt! Everyone dismount and have a drink.” That was all the drill we got.43

It is interesting to note that the order Charlie gave his troop, “Mount, Walk, Trot,” was the very same order given to Metis hunters by their captains during earlier buffalo hunts. The context, however, suggests Charlie was a more cavalier leader. Despite any new perceptions of Indigenous people he now encountered, Charlie (and many others) did not take their duties about protecting against Indigenous people very seriously at all. When Isabella Hardisty Lougheed’s brother, Frank Hardisty, also a Rocky Mountain Ranger, was interviewed in 1945, he reported that when the fighting broke out in 1885, he “had a damn good time—and I didn’t kill any Indians either.”44 A Winnipeg Tribune article represented Hardisty as having

organized the Rocky Mountain Rangers and their job was to persuade Chief Crowfoot, of the Blackfeet tribe, to keep his 8000 warriors out of the uprising. He succeeded in doing so, and was quoted as saying that “The chief was a fine man. If he had given his men the word Calgary would have been wiped out in half an hour.”45

Charlie’s role as one of the commanding officers of the Rocky Mountain Rangers, whose most common order appeared to be to “dismount and have a drink,” is somewhat farcical. In reality, we know the rebels that Charlie was ostensibly guarding against were the very rebels with whom he likely shared a closer affinity than members of his new community in Pincher Creek. For her part, Marie Rose seemed to see the activities of the Home Guard, the precursor of the Rocky Mountain Rangers, as farcical as well. She wrote that most of the duties for Kootenai Brown and his friends, the Rangers (one of which was her husband), consisted of being “fired up” with “Jamaica Ginger.”46 It appears that Marie Rose did not take the threat of danger by Indigenous people in 1885 any more seriously than her husband did.

Although Charlie appears only briefly in Marie Rose’s writings overall, most of her writing about her husband refers to the difficulties that she, as a young wife and mother, was forced to deal with due to his extensive drinking. Writing of their early years on Jughandle Ranch, Marie Rose noted that, despite having a houseful of children,

any time the mill closed down, the boys would stampede to Charlie’s place and wait for the next cargo of liquor to arrive. They would lie around anywhere, in the kitchen or out under the wagon…We never seemed to be alone in those early, pioneer days.47

In a rare moment in which Marie Rose shared with readers her disgust about the goings-on at the home she shared with Charlie, she wrote, in a segment appropriately titled, “Bits of My Home Life,”

One day I planned to get rid of the whole gang for good and the children and I would be free of all this nonsense. I emptied the barrels, hiding the liquor and replacing it with water, mustard, red pepper and purgative salts. Now do you think that made them sick? No, siree, they drank it all and never knew the difference.48

In another example, it appears that, in addition to writing about her situation, Marie Rose shared her distress about Jughandle Ranch with at least a few in her community. As her contemporary, Ben Montgomery, wrote when describing his conversation with Marie Rose in the late 1930s,

The only time when Mary could feed her children was when all the visitors were asleep. She had an awful time and she used to be mad but would not say a word because Charlie would be cross.49

Marie Rose (whom Montgomery referred to as “Mary”) went on to describe the lengths to which she had to go to keep her children safe during Charlie’s antics:

For the night, Mary used to put all the little folks in one cot against the wall, just like sardines and she would sit at the foot of the cot, watching so that the boys would not lay on her progeny.50

On more than one instance in her writing, Marie Rose indicated that she lacked agency as Charlie’s wife, telling her readers, “You will wonder why I did not object to having the house full all the time…It was no use, Charlie was boss.”51

The reality is that Charlie’s wife was of Metis ancestry, educated by Roman Catholic nuns, and thus had some appreciation for the Western patriarchal ideology the Church adhered to. Marie Rose understood the need to be seen to be obedient to her husband, as is evident in a letter she wrote to Archbishop Taché in 1893. In that letter, Marie Rose appealed, on Charlie’s behalf, and at his insistence, for an explanation of the remainder of her money willed to her by her father.52 It is not clear if the bishop granted Charlie’s request for money. However, perhaps this request had not yielded a favourable response, for Marie Rose made another inquiry in person. The journey she took to Winnipeg with Mrs. McGillis (referred to earlier) now produced a better response from the bishop, for both Marie Rose and her sister were able to withdraw a considerable sum, $1,500, from their father’s estate. Marie Rose used this money in part to replace her horses so she could make the return trip to Pincher Creek on her own, having failed to connect with Charlie.53

When it came to Charlie’s drinking, Marie Rose could not have missed the sentiments of her spiritual advisor, Father Lacombe. Lacombe was featured in the Pincher Creek Echo, explaining the need for a convent in Pincher Creek, the convent for which Marie Rose worked very hard to help raise funds.54 According to Lacombe, the convent was an absolute necessity to educate children, not only with books but also with “civilization,” since the children of ranchers learned the “rough” and “wild” life of the cowboy.55 Although Charlie was not technically a cowboy, those early prairie dwellers who typically led a nomadic life as hired hands, his frequent forays away from home likely rendered his lifestyle no different in Lacombe’s eyes. Marie Rose also wrote, “Father Lacombe often said that the greatest trouble-makers were the American whiskey traders…for the Indian becomes a savage under the influence of ‘fire water.’”56 Of course, the priest likely had no more tolerance for Canadian whiskey traders such as Charlie Smith.

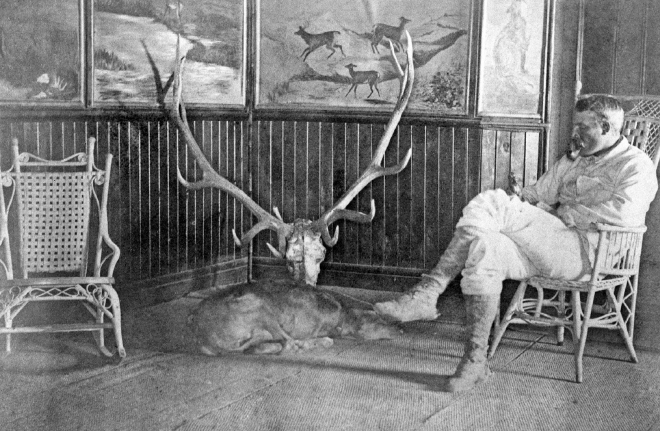

(L–R) Robert Gladstone, Mr. Dumont, Charlie Smith, and Kootenai Brown, in front of Brown’s cabin. Photo undated. Glenbow Alberta Museum and Archives, NA-62-1.

While Father Lacombe may not have held Charlie in high regard, many males in his community may have respected him, or at least felt beholden to Marie Rose’s generous husband. This regard is evident by the presence of other leading community members as pallbearers at Charlie’s funeral, among them the first Member of Parliament for the region, local businessmen, an author, a teacher, a retired police officer, and a land agent, all of whom were notably Euro-North American.57 Perhaps these pallbearers felt beholden to both Charlie and Marie Rose, for it was likely some of these old-timers helped pay for Charlie’s funeral.

It does appear that Charlie came to gain a reputation as somewhat of a folk hero. A publication that appeared in 1995, titled Humorous Cowboy Poetry: A Knee-Slappin’ Gathering, featured a poem by Jim Green with Charlie as the main character. Green was a rancher from southwestern Alberta who also offered his services as a guide.58 The poem, “Jughandle Smith Goes to Town,” poked good fun at the fact that Charlie often returned home in a somewhat unconscious state, but no matter, because his horses knew the way back to the ranch where his young wife always waited.

Charlie’s nomadic lifestyle presented challenges for Marie Rose, so she was no doubt very appreciative of the fact that Charlie had in reality joined the Delorme family. Documents confirm that her mother continued in the Metis fur trade tradition of keeping a close geographic proximity to family members. Although not confirmed in the census, other documents suggest that other members of Marie Rose’s Delorme family lived for periods of time in the Pincher Creek district after Marie Rose and Charlie had settled there. For example, Marie Rose’s brother Urbain does not appear on any of the census documents for the area. Two letters written in 1892 indicate that Urbain Delorme II was in Duck Lake and Batoche and was requesting funds from Bishop Taché, but, in 1894, Urbain wrote a letter from the Pincher Creek area to the bishop, again requesting money from his father’s estate. By this time, Urbain had sold his land grant in the Red River area to his sister Elise Ness.59 Also, on one occasion, Marie Rose wrote that her brother Urbain recovered her democrat after it was upset when her team of horses had spooked, leaving her to walk the five miles home.60 Marriage records also confirm that Urbain married Nellie Gladstone in 1892 in Pincher Creek.61

Marie Rose’s adopted brother, Charlie Ross, whom she had once referred to as the “full-blooded Sioux,” was also likely living in Pincher Creek in 1889, when his daughter was born.62 Marie Rose wrote that Charlie Ross eventually settled in the North, but the fact that his daughter was born in Pincher Creek suggests he also lived there at some point. Although it was not possible to confirm through census documents, Diane Payment wrote that Norbert Delorme, one of Marie Rose’s “rebel” uncles, also settled for a time in Pincher Creek. It is very likely that Norbert was in Pincher Creek, particularly since his wife was the sister of Cuthbert Gervais, Marie Rose’s stepfather. Although he may not have taken a homestead, Norbert could have lived with any one of several family members in the Pincher Creek area. Further, given there was a warrant issued for him after 1885, family members would not likely have been forthcoming with government census workers about Norbert’s whereabouts. Nor would Marie Rose have been forthcoming with this information in her manuscripts.

Marie Rose Delorme Smith and brother Urbain Delorme II, taken in Pincher Creek, Alberta. Photo dated 1900. Glenbow Alberta Museum and Archives, NA-102-12.

Another family member, Marie Rose’s cousin Véronique Gervais Fidler,63 lived for a time at Jughandle Ranch, no doubt contributing to the subsistence economy of the Smith household. Another of Marie Rose’s sisters, Madeleine, and her husband, Ludger Gareau, moved to Pincher Creek in 1886, after their home in Batoche was destroyed during the fighting in 1885.64 Like Marie Rose, Ludger and Madeleine established a ranch in the Pincher Creek district, where they raised cattle and horses.65 Another sister, Elise, who had married George Ness (the man who served as justice of the peace in Batoche in 1885), also settled for a time to ranch in the Pincher Creek district, filing a homestead application near Beauvais Lake on 1 October 1888.66 Apparently, when Ludger Gareau, a self-admitted “admirer of Louis Riel,”67 headed further west to Pincher Creek in 1886, George and Elise Ness joined him and Madeleine. This means there was a two-year span between the time when George and Elise came to the Pincher Creek district and when they filed for a homestead. Many of the Delorme family could have done the same—come to the district and stay with other family members so their names would not necessarily appear in homestead records.

Marie Delorme Gervais also settled in the Pincher Creek district with her husband Cuthbert. The couple had four children, Azelda Gervais Gladstone, Nancy Gervais LeBoeuf, and Joseph and Alex Gervais, all of whom remained in the district.68 Thus, quite a large family network eventually settled near Marie Rose and Charlie after they staked their first homestead in the late 1800s.

Marie Rose also always maintained close contact with the nuns and priests in Pincher Creek. Numerous accounts in the local newspaper confirm that Marie Rose was one of the devoted workers who raised funds so that a convent could be built in Pincher Creek. Descendants still have photos of Marie Rose with various members of the church, and recall that her close relationship with Father Lacombe allowed her to use his rail pass to access medical care. Reporting on her return visit to southern Alberta in 1955, the Pincher Creek Echo still drew attention to the fact that Marie Rose was a “close friend of Father Lacombe, famous missionary among the Indians in Alberta for many years.”69 Although her husband was a whiskey trader and perhaps even a one-time cattle rustler, Marie Rose continued to be held in high regard by Roman Catholic priests and nuns. However, it clearly became important to develop a wider circle of acquaintances as newcomers settled in the area.

In 1955, Marie Rose reminisced that she and Charlie were among the first settlers to the area; the only others she could recall being there were the police.70 Marie Rose wrote that it was 1886 before the first Euro-North American women settled in the district.71 Eventually, more settlers came and some no doubt shared the views expressed by Mary Inderwick. In 1884, this Pincher Creek rancher’s wife wrote to her family in Ontario to say that she encouraged the local men to “go east and marry some really nice girls” as a way to prevent unions with the “squaw,” who was described as the “nominal wife of a white man,” near her ranch.72

While men who married Indigenous women eventually encountered racism like that expressed by Inderwick, Marie Rose indicated that, in 1882, six years after her marriage, “most of the white men had squaws for wives…There we all lived contented as lords.”73 Some of these men who had married “squaws” formed part of Marie Rose’s community of friends in Pincher Creek. However, perhaps because of newcomers like Inderwick, Marie Rose eventually broadened her circle by associating with those who she perceived to be of “aristocratic” or noble birth. Included in her new circle of acquaintances was the British remittance man whom locals referred to as “Lord Lionel.”74 When Lionel Brooke arrived in Pincher Creek in the early 1880s, corporate ranches such as the Waldrond, Oxley, and Cochrane were already operational, as well as many family-based ranches. While he had partnerships in several ranching endeavours, Brooke eventually acquired the Chinook Ranch near Jughandle Ranch.75 Although he seemed determined to “establish himself as a gentleman rancher,” Brooke spent a good portion of his time “traveling around, hunting, fishing, rambling, and camping with the Stoney Indians.”76 Brooke reportedly commented that he “would rather be with the Stony [sic] Indians. To me they are ‘whiter’ than the White man.”77

While they often struggled, these aristocratic remittance men still retained a sense of their own importance. In the new society of the North West, those wishing to achieve some semblance of a higher station in life often sought the company of these remittance men. In Brooke’s case, there were reportedly many of the “rough and ready cowboys” who poked fun at Brooke and his “free-spending ways with money.” However, many hostesses in the ranch country were apparently eager to include Brooke among their guests, likely believing he added a “flavour of aristocratic elegance to a party, for he could be very distinguished looking dressed in his best tweeds with his monocle fixed in one eye.”78

Marie Rose appears to have been just as smitten as most local hostesses, writing that Brooke was involved in the establishment of the aristocratic sport of polo, and that he was a “big man…big Nina among the Indians.” Even more importantly, Brooke had reportedly, according to Marie Rose, “traveled to different places such as Japan, South Africa, Honolulu, West Indies, China, Iceland, Norway, Bermuda, Italy, California, and many other places.”79 Marie Rose may have heard about these travels first-hand or she may have been writing directly from Brooke’s obituary, which appeared in the Lethbridge Herald on 16 January 1939, and which noted some of these travel destinations.80 Most likely, some of her esteem for Brooke came not from what he was and what he was able to produce in a market economy (a standard that many applied at the time) but from his family associations and his connection to distant places.

Lionel Brooke, Pincher Creek, Alberta. Photo dated 1890s.

Glenbow Alberta Museum and Archives, NA-1403-1.

While some of the prairie characters Marie Rose identified as historical figures, such as Lionel Brooke, are not particularly familiar to historians now, to Marie Rose, they appeared worldly. Although she must have had many boarders in her rooming house in Pincher Creek, for this is how she eventually supported her family, she does not name a single boarder other than Brooke, who spent his last years in her home. In addition to the aristocratic air they provided, free-spending remittance men such as Brooke were very important to local boosters, given that many relied on the barter and credit systems, and injections of new money were welcome news for local, rural settlements.81 Undoubtedly, Brooke paid for his room and board, thus he and Marie Rose helped each other through the barter and credit systems. However, perhaps Marie Rose also received the benefit of a sense of heightened status, for it was her home that Brooke chose for his “retiring life” and where he died in 1939, at “well over 80 years of age.”82

Marie Rose also wanted readers to know that among her community of connections was a man who has become somewhat of a folk hero, Kootenai Brown. Impressed by Brown’s “courtly manners,” she wrote in her unpublished manuscript, “Eighty Years on the Plains,” that she wanted to devote “a full chapter to John George Brown, better known as Kootenai Brown.”83

Brown was born in Ireland and immigrated to Canada after serving in the British Army in India. He first travelled to the Waterton Lakes area in 1865, settling there in 1877. He was active in the Caribou Gold Rush, and often traded with the Kootenay people, a habit that likely led to his name. When the nomadic trading lifestyle no longer proved economically sound, Brown settled in the Waterton Lakes district, often predicting to friends that the area would one day be a major tourist destination. When the Dominion government created Kootenay Forest Reserve in 1895 as a way to preserve the Waterton Lakes and surrounding parkland for future generations, Brown became its first acting superintendent. Aside from his worldliness, there was even more reason for Marie Rose to forge her connection with Kootenai Brown, for his first wife was Olive D’Lonais, a Metis woman who had also attended the St. Boniface convent. Marie Rose was proud to refer to Olive, not because she identified her as a Metis woman but as a member of her “Alma Mater.”84

Although she had a connection to Olive, it was on Kootenai that Marie Rose focused more of her attention. She noted that Brown was a clever, well-educated man who was to become one of the first homesteaders before the time of surveys.85 As she wrote, Brown was a “great reader and no fool…It was interesting to listen to this man, he was well posted on any subject.”86 She pointed out that Kootenai was not merely an acquaintance but “a great friend to Charlie and me. We visited him many, many times and he came to stay with us so often.” Demonstrating some admiration, Marie Rose wrote of Kootenai, “Like the rest of the oldtimers, he liked the wild life of the plains, though he never lost his gentlemanly ways and might be called a regular ‘Ladies man.’”87

In addition to clearly enjoying his company, Kootenai Brown provided Marie Rose the opportunity to feel like one of her community’s important citizens. Relating his memories also allowed her to write about Indigenous customs from the perspective of a third-person observer, as she did with her own mother’s stories. According to Marie Rose, Brown and Ni-ti-mous (the Indigenous woman he married after Olive’s death) would sometimes be away for “three or four weeks…On one of these trips they were compelled to go right through to Flat Head country, and they stayed with these Indians for a week.”88 According to Marie Rose, Brown

often witnessed the slaughtering of buffalo by the Indians. Out of big logs they built a round corral, very high, and on each side, at the entrance, were built wings, also very high, through which the buffalo were coaxed to enter. An Indian, called a “coaxer,” dressed himself in a buffalo hide, horns and all, to resemble a buffalo as much as possible, and mingled with the herd, bellowing like one of them, and endeavouring to get them to follow him, and lead them to the entry of the corral. Buffalo run in single file, and as they followed the false leader, many riders came behind making a great deal of noise to keep the animals advancing. When all have been coaxed into the trap, a gate, made of heavy logs is dropped into place. The Indians got on top of the corral and began their slaughter. They used flint lock gun if possible, but since few had these and ammunition was scarce, they resorted to the bows and arrows to carry on the killing…The Indians called the corrals, “Buffalo ponds,” and as the slaughter continued, the frightened animals ran about and piled upon one another until the last one was slain.89

(L–R standing) Mrs. Scheer, Ed Larkin, Marie Rose Delorme Smith. (Seated) Ni-ti-mous, Kootenai Brown’s wife. Photo dated 1910s. Glenbow Alberta Museum and Archives NA-2539-10, copied from Provincial Archives 385-2.

This detailed accounting of the buffalo hunt suggests Marie Rose witnessed it herself, but she preferred to tell it as she heard it from Brown.

Although Marie Rose was smitten by newcomers, such as Lionel Brooke and Kootenai Brown, one Indigenous woman did merit some mention in her manuscripts. Kootenai Brown’s “squaw wife,” Ni-ti-mous, who stayed at Jughandle briefly, is the only Indigenous person Marie Rose openly identifies as part of the new network she cultivated during the transitional period. Marie Rose admired Ni-ti-mous’s abilities, writing, “Mrs. Brown…made many rabbit robes which commanded a high price and I was honoured to receive one as her very good friend.”90 Despite her admiration for Kootenai, Marie Rose supported his Indigenous wife over him on at least one occasion. When Ni-ti-mous was told to leave the home she shared with Brown in favour of two Euro-North American women with whom he had been keeping company, Marie Rose encouraged her friend to stand her ground.91

On another extreme, but equally representative of the eclectic company she kept, Marie Rose wanted readers to know that her neighbour was Colonel James Macleod, the North West Mounted Police officer.92 Macleod had taken a homestead near Marie Rose in the Pincher Creek area, and she often wrote about visiting his home, relating that she and others in the district referred to Macleod’s “colored” housemaid as “Auntie.”93 “Auntie” was actually Annie Saunders, who served as nanny to Colonel Macleod’s children after meeting Mary Drever Macleod on a steamboat travelling the Missouri River from Fort Benton, Montana. Annie lived with the Macleods from 1877 to 1880. She then became one of Alberta’s earliest business people of any gender, operating a laundry, restaurant, and boarding house in Pincher Creek.94

Another connection to somebody who is now a well-known historical character, but who was not so widely recognized when Marie Rose knew him, was Frederick Haultain. Marie Rose gives the sense that Haultain, as premier of the North-West Territories, was a regular visitor to Jughandle Ranch, and that he “would come up to these reunions as one of the boys.”95 Haultain was actually a highly educated man who had studied Classics and went on to achieve political success. Haultain remained a respected public figure his entire life.96

In another evident moment of name-dropping, Marie Rose could not help letting readers know that she knew “the Honorable Justice Ives of the Supreme Court of Alberta…from [her] youth.”97 One of the other important visitors to the ranch worthy of mention was D.W. Davis (Marie Rose spells his name “Davies”) who, according to Marie Rose, was the first representative of the district in Ottawa. Interestingly, Marie Rose wrote about Davis that, although he had married a “squaw” and had three children, “Davies was very proud of his family.”98 It was on this occasion that she observed, “White blood mixed with red makes strong and healthy people.”99 It is perhaps ironic that Davis was a former whiskey trader, like Charlie, and a notorious one at that. Reverend John McDougall reportedly said of Donald W. Davis that he was “the wildest type” of trader who had promised to flood the country with whiskey.100 Davis was an American veteran who had eventually landed at Fort Whoop-Up, and who later reworked his image so he could profit in the new era as a merchandise trader in Calgary.101 No doubt it was this reworked image that led Marie Rose to “drop” his name in her manuscript.

Marie Rose loved to tell the stories of those she called her “true friends,” who were likely seen by contemporaries as having achieved some success and notoriety. Among them was a man she called Henry Riviere, who most knew better as “Frenchy.” Marie Rose repeated stories Riviere had related to her about joining the gang of “one of the most notorious cattle men in Montana, Pat Dooley, whose outfit was known as the Dooley Gang.” Although she related the story as though it was personally told to her by the well-travelled Frenchy, there is a letter in her files in which Henry Riviere responds to Marie Rose’s written request for details of his life. While there is no record of Riviere making the claim, Marie Rose wrote that he was a descendant of French aristocracy.102

Nonetheless, Marie Rose indicated that, after cutting ties with Dooley, Riviere settled in Pincher Creek, taking jobs as a park ranger, an actor in Hollywood movies, and an entertainer of tourists at the Prince of Wales Hotel in Waterton, where he told them “wild west stories of the plains in the pioneer days.” Although Marie Rose referred to Riviere as “Frenchy,” he had apparently openly adopted some of the Metis culture, for Marie Rose described Riviere as

wearing mostly buckskin garments, one of those Hudson’s Bay sashes and a fire bag all beaded and heavily fringed hanging in front, his cap is made of some wild looking fur and beaded moccasins. He has travelled extensively in the country and talks French, English and Cree.103

These new acquaintances to whom Marie Rose devoted so much attention in her manuscripts—Lionel Brooke, Kootenai Brown, and Frenchy Riviere—were men who most often followed a nomadic lifestyle but who garnered the respect of the transitional society of Pincher Creek.

When describing some of the activities her new community of acquaintances enjoyed, Marie Rose mostly refered to them as French rather than Metis customs. For example, she described the traditions of New Year’s Day, when her family and friends in Pincher Creek followed the

old French custom for children to visit their parents and receive a blessing from the head of the household. There is much kissing and hand shaking as we greet one another and shout, “Happy New Year,” before we sit down for breakfast…Many friends and relatives were there; toasts were drunk to the heads of the household and we were soon enjoying a real French New Year’s breakfast.104

In the published version of this excerpt, Marie Rose interjected that the Chinook winds that melted the snow one particular New Year’s Day produced the sentiment, “C’est pas croyable.”105 While this New Year’s tradition was a French one, there are many instances of the custom being followed by the HBC men, many of who were actually country-born and who were stationed at the various northern trading posts.

Although the persona she was constructing was that of an English-speaking pioneer, Marie Rose still assumed many duties that were no doubt similar to those she had witnessed of her mother on the trail. While she may not have been skinning buffalo like her mother had, Marie Rose continued to tan the hides she received from Indigenous people in exchange for food. With these hides, Marie Rose made clothing, both for her family and for sale to Euro-North American settlers, men who worked the rail lines and the ranches, and for tourists.

Marie Rose had seventeen children (no doubt influenced by her Roman Catholic beliefs), and her descriptions of child care suggest her economic situation was hardly equal to some Metis women such as Isabella Hardisty Lougheed. While she did have hired help at times, Marie Rose explained her more traditional techniques of child care, how she

raised [her] babies in the early days…I always had a hammock made of two ropes, stretched by a piece of rawhide, then we would put a blanket between the two ropes and a pillow. We never took the baby out of the hammock to feed it, we would stand near the hammock.106

Marie Rose continued “When through feeding, I would give the hammock a push and go back to my work.” Marie Rose wrote that, just as her mother had done,

We also used what we called a baby bag, laced with strings, into which we put the baby. When we untied him, about three times a day, the little fellow would stretch for all he was worth…The reason we used these bags, we had no safety pins in those days.107

In some instances, Marie Rose expressed the same sentiment as many around her may have. For example, she wrote, “With the coming of the settlers, coal oil lamps were introduced to us, but we would not use them as we were afraid they would explode, and moreover lamps were costly to buy.”108 Consequently, Marie Rose continued to use animal grease and rags for lamps and candles.

When she was first married, because the economy remained in transition for such a long period, Marie Rose was able to move between seasonal occupations quite successfully, and thus she had access to many items that would have been appealing for trade. During the summer, there were berries to pick and gardens to cultivate and many other duties. Most early ranchers, including some of the larger leaseholders, let their cattle graze on the open prairie, or, as historian Warren Elofson puts it, they allowed their “livestock to roam the wilds, fending for themselves most of the time.”109 Still, though, in the summer and fall, wild hay had to be gathered for winter feed. Cattle brought in from Montana were normally sold to local men such as police officers110 or traded with Indigenous people.

Also in the fall, Marie Rose would trade with First Nation people for the material needed to maintain her cottage industry of Metis handiwork. The people she most likely traded with on a more regular basis than the Kootenai, mentioned earlier, would have been the Blood, who occupied the Milk River Ridge and the foothills southwest of Lethbridge; the Peigans of the Porcupine Hills northwest of Fort Macleod; the Stoney (likely the Bearspaw, Chiniki, and Wesley of the Nakoda nations) from the foothills west of Calgary; or the Blackfoot along the Bow River near Gleichen.111

Given her knowledge, experience, and extended network of connections, Marie Rose enjoyed more independence than did many new women to the area. It may seem a trivial occurrence, but given that she spoke little of her personal feelings, one moment in particular speaks to Marie Rose’s increasing independence. She wrote,

When we came into this country and settled…I had no neighbors of any kind around me so sometimes I would get very lonesome. One day I thought I would go to visit some friends who were living at the head of Mill Creek cutting logs. I asked my husband, Charlie Smith, to let me have a gentle team.

When Charlie objected, Marie Rose wrote, “Determined to go, I said, ‘I will follow the tracks…I prepared for my wild trip, putting up a lunch for the children.’”112

The fact that Charlie agreed to let his young family venture into conditions that would have been seen as “primitive” by their new neighbours suggests that he either had confidence in Marie Rose’s survival skills or he felt she would do what she wanted despite his objections. On this particular occasion, Marie Rose eventually found her friends, but not without mishap. The roads had been muddied since her last trip, and Marie Rose became disoriented on the rudimentary trails. She had to leave the children in the democrat and walk the final miles until she found the log camp. Men were sent out to recover the democrat and the children, and Marie Rose expressed relief, fear, and some degree of pride in having survived her ordeal.

For the most part, though, Marie Rose stayed on the ranch and managed the couple’s livelihood in Pincher Creek. However, in 1882, she again took to the open trail without the help of her husband. The situation that led to this trip began when Charlie left in the spring to travel to Winnipeg, leaving Marie Rose with her three boys and a hired man to look after the cattle and horses. Carrying on for some time independently, Marie Rose grew “lonesome with only my small children.’’ She decided she would “rather suffer hardships of the trail than be subjected to the ugly attentions of this hireling.”113 Clearly feeling less vulnerable on the trail than on the ranch, Marie Rose

made ready for the trip, heading toward Winnipeg, with a covered democrat, five head of horses, a tent, the necessary clothing and food enough to last until I would meet my husband, some where on his route back.114

This was the trip mentioned briefly earlier in which Mrs. McGillis joined her.

Marie Rose never did meet up with Charlie, but she made it to Winnipeg, some nine hundred miles across country. This was a journey that few “new” pioneer women to the West would have survived. Although accompanied for part of the journey by a local man who was also headed in the same direction, that Marie Rose would undertake such a journey without her husband suggests an enduring confidence in her own abilities. On the way back at the end of the summer, her mother and stepfather, who had yet to settle in the district, accompanied Marie Rose to Jughandle Ranch. When she arrived, Marie Rose was greeted by a worried husband, clearly relieved to have his family back home safely.

Despite his methods, or perhaps thanks to them, there was a time when Charlie and Marie Rose formed a part of southern Alberta’s ranching elite, at least if we are to judge by material wealth. Their proceeds allowed them to take a homestead and to amass a fair sum of property at one point. According to an interview given on his one hundredth birthday, J.R. “Bob” Smith claimed that his parents, Marie Rose and Charlie, once “ran a herd of 1,000 head of cattle on the Jughandle.”115 The one thousand head of cattle that Marie Rose and Charlie reportedly had at one time was not necessarily large compared to some of the early companies that were granted leases of land by the Canadian government. For example, shortly after the government announced a program to lease rangeland for the extremely low rate of $10 per year for every one thousand acres,116 Senator Matthew Cochrane of Quebec leased his first 134,000 acres west of Calgary, to which he brought a herd of over 6,600 head.117

While their holdings were nowhere near those of absentee leaseholders like Cochrane, the 1906 census confirmed that Charlie and Marie Rose held considerable property for an individual couple compared to other Metis people in the Pincher Creek area.118 For example, this census listed Marie Rose and Charlie’s property as including two hundred horses, five milk cows, two hundred horned cattle, and four hogs. In comparison, that same year, Marie Rose’s stepfather and mother, Cuthbert and Marie, had nine horses, four milk cows, six horned cattle, and four hogs. The smaller amount of stock could have been due to the fact that her parents were older and perhaps not as capable of managing a larger herd. Yet, at the same time, Marie Rose’s stepsister Zilda and her husband, Robert Gladstone, had only eleven horses, eight milk cows, sixty horned cattle, and no hogs.119 In fact, the average for new, individual homesteading couples on the prairies, a few years after the 1906 census, was still forty or fifty head of cattle.120

That Marie Rose and Charlie had two hundred head of horses suggests they were also likely involved in a breeding program of some sort. While some breeders exported their horses overseas, Charlie was involved in horse racing (a custom very familiar to his Metis wife) and may have been breeding horses for the local market as well. In one instance, in approximately 1902, when Charlie was making application for the adjacent homestead he had been using as pasture land, he stated that he owned four hundred horses.121 Horse racing was a common activity for the Metis during the fur trade and Charlie’s close association to the Metis would have given him some familiarity with it. Although Marie Rose did not speak at great length about Charlie’s involvement in race horsing, she did say that, in a severe snowstorm in 1903, many horses and cattle were lost, including “two race horses belonging to Charley [sic] Smith…beautiful well-bred horses named Flying Fox and Wolf, both had taken good money on several occasions.”122 She also once wrote of the “splendid breeds of horseflesh, for which Pincher became noted.”123

Conversations with Marie Rose’s granddaughter, Shirley-Mae McCargar, indicate that most descendants believed her grandparents were “wealthy” when they ranched.124 Yet Charlie and Marie Rose had settled on land that would not easily guarantee continued wealth and success. Cattle ranchers endured many setbacks due to prairie conditions, not the least of which were the extremes of weather. The particularly bad winter of 1886–1887 was referred to by some cattlemen as the worst experienced to date in southern Alberta, where some losses were especially high. Ranchers in the Pincher Creek area lost 20 to 25 per cent of their herds that year.125 Elofson noted that years like these taught larger operators to emulate smaller operators, like those in the Pincher Creek district, who had “put up sufficient supplies of hay and had fenced in their herds,” and thus “minimiz [ed] their losses.”126 While the practice of fencing and putting up hay helped, more bitter weather continued to wreak havoc on prairie stock. In 1892, ranchers endured what was later referred to as the “bitterest blizzard in twenty years.”127

Another challenge for homesteaders in the Prairie West such as Marie Rose and Charlie was the persistent fires that often followed new rail lines. These fires were destructive to the wooden buildings of the new towns on the prairies, and could be equally devastating to cattle ranchers. With no gravel and asphalt roads or cultivated fields to serve as fire guards, early prairie fires, set off by anything from lighting to sparks from steam-driven trains, could consume much-needed pasture and ranch stock in very little time.128 Charlie and Marie Rose would have suffered other severe losses along the way, as did most cattle ranchers. In the example mentioned above, during the winter of 1886–1887, when many in the Pincher Creek district lost the majority of their herds, Marie Rose and Charlie were surviving primarily by cattle ranching.129

In addition, for the better part of his life, Charlie had been a hard-drinking man. While we have no real specifics regarding the changes in their financial situation until after Charlie died, Marie Rose and Charlie may have fallen upon hard times while still on Jughandle Ranch. In 1906, a local newspaper reported that Charlie was summoned to appear before a court to answer to the charge of stealing a cow, and then released on bail of $1,500, a considerable sum at the time.130 This charge occurred only four years after Charlie had stated in his application to claim the adjacent homestead that he owned four hundred horses. Attempts to determine whether Charlie was ever found guilty of cattle theft were unsuccessful.131 Nevertheless, it may also be that Charlie was still operating under the rule of law of earlier ranching days, in which unbranded maverick cows were open game, a practice discussed by Marie Rose in her manuscript, “Adventures of the Wild West of 1870.” Despite this example of foolhardiness, and perhaps of criminal activity, Charlie was still recognized in his obituary as one of the leading members of Pincher Creek society,132 no doubt in part because of Marie Rose’s ability to build relationships with many of the leading members of that society.

Certainly, stealing one cow did not equal the major thefts that went on in the early cattle business of southern Alberta. As Elofson found, “There was in fact so much rustling going on that it can be categorized into several clearly recognizable types.”133 Marie Rose spoke about the extensive rustling: “In those days everything looked bright and prosperous. Whereever [sic] you went, you saw riders looking for mavericks in a bunch of cattle.”134 She went on to explain,

Some of the readers may not understand the meaning of “maverick.” It means calves without a brand. The law was not very severe those days. Rustling a maverick was a joke.135

According to Elofson, even larger operators sometimes took possession of unmarked animals by quickly branding them.136

Although any suggestion of cattle theft by Charlie would be difficult for Marie Rose, there was an aspect of family life she spoke of fondly—that of being a mother. She wrote, “My happiest days were when they were all small, contented to see them around me, working for them and labouring for them.”137 As she wrote of the years raising her large family,

I scarcely had time to pick my babies up, even to nurse them, but would stand beside the high hammock until the baby nursed his fill, then covering my breast and giving the rope a push, I went about my work while the swinging cradle lulled the baby to sleep.138

Aside from following the pattern of obedience in Metis families, Marie Rose also followed a pattern identified by scholars in regard to childbearing among Roman Catholic women.139 Marie Rose’s first child, Joseph, was born one year into her marriage on 12 July 1878, at Chicken Prairie, North-West Territories.140 The 1881 “Household Census of the Bow River, North-West Territories District” indicates that Charlie and Marie Rose had two sons at that time, Joseph, aged three years, and Charles, aged one year.141 By the time of the 1901 census, the family in the Pincher Creek district had grown to include seven sons and two daughters.142 Marie Rose assumed the role of new mother every successive year from 1878 until 1904.

While records were not located for all of Marie Rose’s children, those that were indicate she and Charlie relied on both fictive and blood kin as godparents, no doubt as a way to extend their family connections. For Jean Theodore, born in 1894, Marie Rose chose two members of her Delorme family, Ludger Gareau and Azilda Gervais, as godparents. For her younger son, Charles Frederick, Marie Rose chose James Gilruth, a local Euro-North American resident.143 These choices suggest that, during the earlier transitional phase of the Prairie West, Marie Rose continued to rely on the fur trade connections of the Delorme family, but as more settlers arrived, she began to incorporate people other than family members as godparents.

Other than who the children’s godparents were, it is difficult to learn much about her children from Marie Rose’s manuscripts, so it is challenging to understand how they fared in the new economy of the North West. However, she provided some details about the deaths of three of those children, which helps us understand the family dynamics. She had consented to send one child, Mary Ann, to a convent in Valleyfield, Quebec, at the suggestion of the man who was described as her close confidant for most of her life, Father Albert Lacombe. In 1897, shortly after being enrolled by Lacombe in the Convent of Holy Names in Valleyfield, Quebec, young Mary Ann fell ill.144 A letter dated 20 November 1897 from the nuns to Mr. and Mrs. Smith confirmed that, on 18 November, “Mary Ann was taken sick with the croup.” The Sisters continued that Mary Ann’s illness came on so suddenly there was no opportunity to warn the family of the “danger that threatened her life.”145 According to Jock Carpenter, Marie Rose vowed, after Mary Ann’s death, that she would never again send a child away to school.146 Most of the other children did not attend school until they could be accommodated in Pincher Creek.

Although Carpenter wrote that Marie Rose vowed to keep all of her children at home, one daughter, Françoise Josephine, was later enrolled in a school away from home at the Sacred Heart Convent in Calgary. At fifteen years of age, Françoise Josephine was older than Mary Ann had been when she was sent to Quebec, but both girls were enrolled by Father Lacombe.147 Another daughter, Mary Hélène, was also later a resident of an institution operated by the church, albeit not far from home in the town of Pincher Creek, at Kermaria convent. This convent was a project of Father Lacombe’s, for which Marie Rose helped in fundraising efforts.148

Charlie Smith, Marie Rose Delorme Smith, and daughter Mary Ann, taken in southern Alberta. Photo dated 1890s. Glenbow Alberta Museum and Archives, NA-2539-1, copied from Provincial Archives 385-15.

Marie Rose never expressed any sort of remorse toward Father Lacombe for having advised her to send Mary Ann away, although it appears the decision was not totally hers. She wrote that she “had to send a nice girl to school in [the] east.”149 Marie Rose would have understood how much it would mean to Father Lacombe that her daughter be educated at a convent in the same way she had been. Despite her extreme sorrow about the loss of the young girl she felt she had to send away, in her written texts, Marie Rose continued to demonstrate an unquestioning admiration for the priest, writing that no other man had “done as much for this country as Fr. Lacombe…in heaven he still prays for us.”150 In fact, Lacombe felt quite strongly about the need for Christian education for Indigenous children, particularly those on reserves. In 1885, he had gone so far as to urge the government to allow the industrial school near High River to remove children forcibly from reserves, because parents were “determined not to give up their younger children, unless compelled to do so.”151

Marie Rose also spoke about her two sons, whom she lost to the First World War. She introduced readers to the fact that her sons had enlisted in the army shortly after describing the death of her husband, her “comrade of thirty-seven years,” and the death of her eldest son and that of her nine-year-old daughter, all three to illness. Despite these devastating losses, Marie Rose described “her greatest sorrow” as that felt when her three youngest sons “proudly entered the house wearing red ribbons,” signalling their eagerness to serve as soldiers.152 Marie Rose wrote, “I never dreamed that I had raised boys to go to so cruel a war.” She continued that she would “never forget that awful wicked war…I still carry a sore spot in my heart, will carry it to my grave.”153

The fact that the boys enlisted in the war shortly after Charlie’s death, leaving her to fend for her family alone, may have given Marie Rose even more cause to be concerned for the welfare of her sons and the stability of her family. She was in the midst of dire financial conditions and was unable to sell her land for some years after Charlie’s death.

It is not clear why the three sons decided to enlist, but it may have been partly due to economics. Despite any connections that Marie Rose was able to foster, her sons were still Metis men, whose parents were no longer as wealthy as her descendants believe they once were. Other than the two sons lost to war, her other sons all pursued labouring work. Given the changing conditions of the Prairie West, there were few other options for young Metis men than to pursue labouring jobs, and often times those jobs put them at risk of physical harm. Had he not fallen from a moving train and been killed, one son, Michael, may have been following the path of “itinerant cross-border labourers” who rode the rails between Montana and western Canada, serving the natural resource industries of mining, lumbering, and grain and livestock production from 1870 and 1920.154

There were several factors that speak to the likelihood that Charlie was not able to assist his sons in establishing themselves: he was almost twenty years older than his wife; he was a whiskey and robe trader in a changing economy; he lacked skills to function well in a society increasingly reliant on paper transactions; and he appeared at the least inattentive to obtaining proper documentation that would ensure his family was cared for upon his death. Thus, Marie Rose’s sons likely felt a need to embark on risky careers, such as riding the rails or enlisting in war. As for Marie Rose’s daughters, it appears they fared at least better than the boys. One daughter, Eva, married a member of the Royal North West Mounted Police and, according to Jock Carpenter’s genealogical chart155 and other family documents, the other daughters all married Euro-North American (and, perhaps not coincidentally, non-French) men connected to the new economy.

Although it was necessary to accept independence when her older husband was ill or away, Marie Rose always described the circumstances of her married life as though she had little say in the decisions, at least in the first years of her marriage. She wrote,

He decided to take up land to homestead. After scouring the province from north to south, he decided on a sheltered spot on the banks of Pincher Creek…To this spot he brought two hundred and fifty head of cattle. He brought these from Montana, thinking he would live a quiet, independent life with his family. He called it the Old Jug Handle Ranch…“Jug Handle” was the mark on the neck of the cattle; the loose skin was cut left hanging like a handle. To all friends or foe, strangers or neighbors were welcome day or night and no one ever left the spot hungry, Indian or white man.156

Yet Marie Rose lived almost a lifetime, forty-six years, as a widow in a new economy increasingly removed from the fur trade. It is understandable, then, that not only would her children have to establish themselves with little parental assistance but Marie Rose, herself, would have to become fairly independent. In fact, there were traces of independence throughout her married life that belie the simplistic conclusion that she was always an obedient wife without agency. Indeed, these traces of independence likely inspired Marie Rose to refer to herself in her manuscripts as Queen of the Jughandle.

It is informative to understand how Marie Rose managed while Charlie was away for extended periods when they were still on the ranch by relying on skills that enabled her to survive as a widow. It appears the largest herd Marie Rose and Charlie may have had was approximately one thousand head. In the days of open-range grazing, relatively little labour needed to be expended, given that “Cattlemen simply allowed their herds to roam the open range summer and winter…For the most time this required a work force of only one man per thousand head of cattle.”157 Given that Marie Rose and Charlie’s family would grow to include seventeen children, and that many of her Delorme family lived nearby, farm labour would have been plentiful. Furthermore, the scarcity of women on the prairies likely gave those that were there a sense of their own stature and potential.

For her part, Marie Rose functioned quite well as a young married woman, and she prided herself on being an able rancher. In reality, many early homesteaders and ranch women simply did what had to be done. If that meant operating the ranch while one’s husband was away, as Charlie so often was, then that would simply seem a natural undertaking. Yet, even if it may have been the natural thing to do, Marie Rose noted a heightened sense of her own abilities, writing,

With my buckskin work of shirts, gloves and all wearing garments; tents for habitation; cooking in my boarding house; and running a homestead, you will think that I never hesitated to lay my hand to any work that called for my attention.158

Marie Rose’s relative independence, recognized by even the Roman Catholic Church authorities, was an anomaly, not only in Roman Catholic teachings at the time but in a society increasingly oriented to Victorian values. According to her granddaughter, Jock Carpenter, although Charlie was still alive at the time, it was Marie Rose who was approached by the Roman Catholic priests in Pincher Creek about investing in property in the townsite near the church, and it was Marie Rose who made the decision to do that.159 This decision-making role is not only unusual for the times but also for Marie Rose and Charlie’s own relationship because, according to Carpenter, “Charley [sic] did not like her [Marie Rose] trying to boss him. He was boss, even though she now did all the business for the ranch.”160 There is a possibility that the money to purchase the property next to the church was drawn from the inheritance of her father’s estate, and this partly explains why the priests would have approached Marie Rose.

Yet it may have been her growing independence and her Roman Catholic teachings on the sanctity of marriage that inspired Marie Rose to take a position against a practice that had been common during the fur trade, that of “turning off” Indigenous partners.161 As mentioned briefly earlier, when Kootenai Brown, a man whom she clearly admired, told his partner, Ni-ti-mous, that she would have to leave her home so he could continue keeping company with two Euro-North American women, Marie Rose came to her defence. She encouraged Kootenai’s country wife, telling her, “He can’t quit you, nor can he marry again…that’s your home he can’t put you out.”162 Marie Rose delighted in telling the story that Kootenai soon came to his senses, and that he had to give Ni-ti-mous ten dollars, his “bunch of horses,” as well as his brand and “a wagon and a load of grub” to convince her to return.163

Marie Rose also commented on other marital arrangements she observed in her community. For example, she wrote that, even during the early years of settlement, in 1883, when “white men lived with squaws,” many of these Indigenous women enlisted the help of a local dressmaker, who made “good money”164 dressing them in ways that would be fitting for the new settlers to the area. She observed that many of these young “squaws” were “proud to dress like their white sisters.”165 While it may be so that Indigenous women were beginning to “dress like their white sisters,” practicality during the early transitional period would have necessitated a continued reliance on traditional garments. It was the continued reliance on these traditional garments that allowed Marie Rose some independence and “pocket money.”

Indeed, because of the many diverse ways in which she participated in the economy, Marie Rose was always able to say she had “pocket money” for herself and her children. While seamstress work was common by the nineteenth century and increasingly catered to women in the upper classes, Marie Rose also profited from seamstress work, but for the most part her work was not intended to meet the needs of the upper classes. According to her documents, she worked primarily for the men working the range and the rail lines, and to satisfy the needs of a growing tourism industry by making traditional garments.

While there are few details about Marie Rose’s own clothing, there are traces that suggest some of the traditional Metis garments continued to be worn by her children; thus, she was not only producing items for sale. In one example, Marie Rose wrote that, on her way to church with three of her children on a very stormy winter Sunday, the children were “covered with badger robes.” According to Marie Rose, the robes were more than adequate to keep her children warm. On the other hand, a “poor unfortunate” newcomer to the area, working in the Christie mine down the road from her home, was deemed not “very well dressed for this kind of weather.” The newcomer turned down her offer of assistance when she came upon him on her return trip from church and was later “found frozen in a coulee.”166

Jock Carpenter explained that, in addition to relying on traditional skills to feed and clothe her family, Marie Rose “let it be known that she would take in boarders and ladies-in waiting. Women, feeling that their time to deliver was near, moved into the big house.” Carpenter continued,

Marie Rose’s midwifery, carried on while she was at the ranch, and increased later when she had moved the family into the town of Pincher Creek. The Indians too, came to town as they had done on the ranch, seeking treatment for eye infections.167

Describing traditions that were no doubt relayed to her by her own mother, Carpenter wrote, “Boiling a herb the way Mother Gervais [Marie Delorme Gervais] taught her, Marie Rose bathed the infected eyes with the cooled liquid and soon the redness and draining disappeared.”168

Eventually, the growing reliance on Euro-North American health care in the new society of the North West led the government to order Marie Rose to stop using some of her traditional skills. According to her granddaughter,

Marie Rose had put in many years of midwifery and the doctors were disgruntled at not being called to deliver the babies. Soon Marie Rose had a letter from officials in Edmonton telling her that she must desist from this practice.169

It is very likely that, despite pressure from government officials, Marie Rose continued in her role as healer, given that she maintained a book filled with samples of Indigenous-inspired natural remedies until her death in 1960. While her descendants could no longer locate the medicinal book Marie Rose kept throughout her life, they recall that the book even contained samples of natural products she used when practising traditional healing.

Marie Rose did not reveal directly to readers that she relied on traditional skills to help feed her family, but the history that Mary Hélène Parfitt shared with her daughter Jock Carpenter confirms that she did. Carpenter wrote that her mother remembered being told that Marie Rose had learned many of the Metis customs from her own mother and that she carried on with those customs. Mary Hélène also recalled that her mother, in addition to her work as a midwife, “spent countless hours making buckskin articles.”170

Mary Hélène confirmed the economic importance of Marie Rose’s work when she observed that the skills Marie Rose learned “at her Mother’s knee,” such as “beading, cooking with native roots and herbs, tanning skins, making soap, drying meat,” helped to keep the family fed and well looked after.171 Just a few years before her death in 1960, Marie Rose was interviewed, and subsequently introduced by Harry Baalim as “this old gal…Buckskin Mary.”172

Without the oral testimony of her descendants, we would not know that Marie Rose was a respected healer and a midwife. In fact, she wrote primarily from the third-person perspective about the childbirth experience of the first Euro-North American woman in her district, saying that Mrs. Schoening, the wife of the local blacksmith, gave birth with the help of “kind neighbor women.”173

It is possible that Marie Rose used methods similar to those described for researcher Martha Harroun Foster when she interviewed Spring Creek Metis families. One woman had vivid memories of traditional remedies that consisted of rubbing an afflicted person’s chest with “terrible-smelling goose grease, a favourite Metis remedy.”174 There are similar stories among Metis women in Ontario, including using goose grease to heal coughs, weak tea for snow blindness, black bear bile as liniment, beaver castors for poultices, oil from boiled and strained beaver castors to prevent hemorrhaging after childbirth, and brews from certain plants for various aches and pains.175 In order to have access to the items needed to carry on as a healer, Marie Rose’s social and trading network would have had to be extensive for most of her life.

Although Marie Delorme Gervais had five daughters, some of whom also settled in Pincher Creek, Marie Rose was the only one singled out by locals as having inherited the skill of working with hides. According to Marie Delorme Gervais’s contemporary, she was “quite skilled at tanning hides…Wilbur Lang recalls seeing a beautiful coyote robe she had made. (This talent was inherited by a daughter, Mary Delorme Smith).”176

As she became more renowned for her skills, Marie Rose hired other Metis women to help meet her various contracts with the CPR and the Prince of Wales Hotel. Many of these women may have been family members, for there is some evidence from the oral testimony of her descendants that she did pass on some traditional Metis skills to her own children.177 Family members still retain photographs of Marie Rose’s handiwork, with written notations on the back indicating the models were wearing her garments. There is even one photo of a man wearing traditional First Nation clothing identified by family members as “uncle Dick playing Indian Chief.”178

One of the most important venues at the time for Marie Rose to display her distinctive Metis handiwork may have been the Calgary Stampede. Although she did not say she had participated, Marie Rose wrote that each year the Stampede offered prizes for the “best decorated Indians and Squaws on horse back, the beaded harness aiding in the judges’ decision. It would be difficult, indeed, to match the wonderful display shown there.”179 Immediately after noting this about the Stampede, she wrote, “Much of this work I learned from my mother, and enjoy making original designs on all my buckskin work.”180 The oral testimony of her descendants suggests that Marie Rose’s garments were used for venues such as the Stampede.181

(Back) Mary Hélène Smith (Parfitt). (Front, L–R) Kathleen Victoria Parfitt, Marie Delorme Gervais, Frances Theodora Parfitt, Marie Rose Delorme Smith, Helen Dora Parfitt (baby on lap), Alice Loretta Parfitt. Photo undated. Shirley-Mae McCargar and Donald McCargar.