7 MORAL RIGHTS

The Visual Artists Rights Act (“VARA”), landmark legislation creating moral rights for artists in the United States, was enacted on December 1, 1990, as an amendment to the copyright law and took effect on June 1, 1991. Copyright, the power to control reproduction and other uses of a work, is a property right. Moral rights are best described as rights of personality. Even if the artist has sold a work and the accompanying copyright, the artist would still retain rights of personality.

Prior to the enactment of VARA, the protections for American artists had been limited and often unsatisfactory. While some legal commentators argued that American laws relating to unfair competition, trademarks, right to privacy, protection against defamation, right to publicity, patents, and copyrights amounted to a satisfactory equivalent of moral rights, the better view was that this mélange did not at all approach the protections offered to creative people and their work under specially designed moral-rights provisions. Many artists’ groups recognized moral rights as an important issue and urged the enactment of legislation to guarantee this protection. A number of states responded by enacting pioneer moral rights laws, a trend that helped develop momentum for the enactment of VARA. This chapter will explore the provisions of VARA, compare it to foreign and state laws, and then review other legal theories that protect artists.

The Visual Artists Rights Act

Drafted and shepherded to passage by Senator Edward Kennedy, VARA gives a narrow definition of a work of visual art as “a painting, drawing, print or sculpture.” VARA covers unique works and consecutively numbered limited editions of two hundred or fewer copies of either prints or sculptures, as long as the artist has done the numbering and signed the edition (or, in the case of sculpture, placed another identifying mark of the artist on the work). The limited edition provision also applies to “still photographic images” as long as an edition of two hundred copies or fewer is consecutively numbered and signed by the artist.

This narrow definition limits the effectiveness of VARA. Explicitly excluded from protection under VARA are posters, applied art, motion pictures, audiovisual works, books, magazines, databases, electronic information services, electronic publications, merchandising items, packaging materials, any work made for hire, and any work that is not copyrightable. While VARA protects traditional fine art, it appears that it will have no impact at all on commercial art, which is created for the purpose of reproduction. Of course, one can imagine that a unique painting might be altered before reproduction, in which case the provisions of VARA might apply even though the intention in creating the art was to reproduce it in large quantities.

VARA gives an artist the right to claim authorship of his or her work, to prevent the use of his or her name on the works of others, and to prevent use of his or her name on mutilated or distorted versions of his or her own work, if the changes would injure his or her honor or reputation. In addition, the artist has the right to prevent the mutilation or distortion itself if it will damage the artist’s reputation.

If the artist wants to prevent the destruction of a work, it must be of “recognized stature.” This test for recognized stature is like that under the California law, which is discussed later in this chapter. However, the statute wisely gives artists rights in their own work regardless of recognized stature and reserves the stature test for works that should be preserved for the culture. As cases are decided under VARA, it will be interesting to see where the boundary is drawn to divide works considered to be of recognized stature from those that are not.

The moral rights of the artist cannot be transferred. However, VARA does allow the artist to waive these rights in a written instrument signed by the artist. The wisdom of allowing waivers is certainly open to question in view of the disparity of bargaining strength so often present when artists deal with larger entities. The written instrument of waiver must identify the work and the uses to which the waiver applies, and the waiver is limited to the work and uses specified. For a work created by more than one artist, any of the joint artists has the power to waive the rights for all the artists. The waiver of moral rights does not transfer any right of ownership in the physical work or copies of that work. Nor does the sale of a physical work, a copyright, or any exclusive right of copyright, transfer the artist’s moral rights, which must be exercised by the artist.

For art incorporated in or made part of buildings, VARA seeks to balance the rights of the building owner against those of the artist. If the art would be destroyed or altered by its removal, then the artist has a right to prevent such destruction or modification unless either (1) the art was installed in the building before the effective date of the law, or (2) the artist and owner signed a written instrument in which they specified that the work may be subject to destruction or modification due to removal. On the other hand, if work can be removed without destruction or mutilation, the artist shall have the right to prevent mutilation or destruction unless either the owner makes a “diligent, good faith attempt” to notify the artist of the owner’s intended action or, if the owner succeeds in notifying the artist, the artist does not either remove the work or pay for its removal within 90 days of receiving such notice. Of course, an artist objecting to the destruction of a work incorporated in a building would have to show that the work was of recognized stature.

VARA exempts from its coverage changes in a work of art due to the passage of time, the inherent nature of the work’s materials, conservation or public display.

The term of protection for works created after the effective date of VARA is the artist’s life. This certainly invites the criticism that the term should have been the same as the term of copyright protection. For works created before VARA’s effective date, the artist will have moral rights in works to which he or she holds title, and such moral rights shall last as long as the copyright in the work. This means that works created prior to June 1, 1991, and in which the artist holds title will have a longer term of moral rights protection (the artist’s life plus seventy years) than those works created on or after June 1, 1991. The term of moral rights protection when a work is created jointly by more than one artist is the life of the last surviving artist. All moral rights run to the end of the calendar year in which they would expire.

VARA also requires that a Visual Arts Registry be created in the Copyright Office. The Copyright Office regulations (section 201.25) allow either an artist or building owner to give and update relevant information with respect to art incorporated in buildings, such as the name and address of the artist or owner, the nature of the art (including documenting photographs), identification of the building, contracts respecting the art, and any efforts by the owner to give notice regarding removal of the art. The Copyright Office does not provide a form for giving such information. The fee is $105 for one title and an additional $30 for each group of not more than ten titles.

The enactment of VARA at least extends to visual artists, if not other creators, rights similar to those contained in the Berne Copyright Convention, which provides that “the author shall have the right to claim authorship of the work and to object to any distortion, mutilation or other modification of, or other derogatory action in relation to, the said work, which would be prejudicial to his honor or reputation.”

To understand how VARA will apply to particular situations, and to what degree the law of the United States has been changed by VARA, it is helpful to examine a number of European and American cases illustrating the likely impact of VARA.

VARA gives the artist the right to claim authorship of the artist’s work and to disclaim authorship of works by others. Known as the right of attribution (or paternity), this should prevent enforcement of a contractual provision by which an artist agrees to create work under a pseudonym. In a French case decided in 1967, for example, a painter named Guille agreed to deliver to his dealer his entire output for ten years. These works would either be unsigned by Guille or signed under a pseudonym. The court held the contract invalid, since it violated the painter’s right of attribution.

A limit to the right of attribution is shown in a bizarre 1977 case involving the Surrealist Giorgio de Chirico. He filed suit in France when a painting titled The Ghost and attributed to him was displayed at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. He claimed that the attribution was false and demanded the painting be destroyed. The court insisted that he pay an expert’s fee to examine the painting for authenticity. When de Chirico refused to do this and failed to prove by other means that the painting was a fake, the court not only refused to grant the relief requested but also required de Chirico to pay fifty thousand francs to the woman who owned the painting. The right of attribution would permit an artist to prevent false attribution of a painting, but it would not allow the artist to stop the exhibition of a painting that is correctly attributed.

It is open to question whether VARA would have changed the result in the famous American case involving the artist Alberto Vargas and Esquire magazine. Vargas created a distinctive series of drawings of women over which Esquire acquired complete ownership by contract. For more than five years, Esquire had given Vargas credit as creator of the illustrations, although the contract itself did not provide for him to receive any such credit. After Vargas and Esquire had a falling out in 1946, the magazine changed the title on the remaining drawings it owned to “Esquire Girls” and gave no credit line at all to Vargas. Vargas sued, but the court decided that Vargas could not claim an implied right to receive authorship credit, because the contract specifically transferred all rights to Esquire. It stated, “What plaintiff [Vargas] in reality seeks is a change in the law of this country to conform to that of certain other countries…we are not disposed to make any new law in this respect.” (Vargas v. Esquire, 164 F.2d 522.) Whether VARA would afford any relief in a Vargas-like case today might depend on whether the magazine altered the physical work or not. If the magazine scanned the physical work and left it intact, but altered the digitized image, it seems unlikely that VARA would apply.

Interview with Alberto Vargas

Laws granting moral rights may seem arcane to artists who have never experienced a denial of authorship credit or defacement of an artwork. What do such laws mean in terms of human emotions and the impulses governing creativity? Two cases from the 1940s were invariably cited as authority for the fact that artists in the United States lack moral rights and must protect their reputation and their art by contract. But how did these cases affect the artists, Alberto Vargas and Alfred Crimi, who dared seek legal recourse in vain attempts to gain moral rights? How might moral rights laws affect other artists who find themselves involved in such disputes in the future? To learn the answers to questions such as these, I interviewed both Crimi and Vargas in 1979, more than three decades after the cases that had made their names an enduring part of our legal history. The Crimi interview appears later in this chapter.

Alberto Vargas, well known for his portraits of women, became a pioneer in the field of artist’s rights by waging his famous legal battle against Esquire. While the Vargas decision is known to many artists and lawyers with an interest in the field of creator’s rights, the struggle between Vargas and Esquire is not known.

No problems developed between Vargas and Esquire under his first contract with the magazine, which lasted from June 1940 through May 1944. On May 23, 1944, however, Vargas entered into a new contract with Esquire that required fifty-two drawings each year for a period of ten and a half years. The contract provided, “The drawings also furnished, and also the name ‘Varga’, ‘Varga Girl’, ‘Varga Esq.,’ and any and all names, designs or materials used in connection therewith, shall forever belong exclusively to Esquire, and Esquire shall have all rights with respect thereto…”

In February 1946, Vargas sued in federal court to have the contract canceled. The court decided the contract had been fraudulently obtained and granted Vargas the cancellation, but Esquire later obtained a reversal in the appellate court. In March 1946, after cancellation of the contract, Esquire began calling the Varga Girl drawings by the title of the Esquire Girls. Vargas’s name did not appear with his drawings at all. Vargas then sued to prevent the reproduction of any more of his work by Esquire because Esquire was not giving him credit as the artist for the drawings. But the court refused to grant Vargas his right to receive credit for his work, stating instead that moral rights were not recognized in the United States.

Vargas briefly related his background, speaking with a slight accent, in a conversation frequently punctuated by laughter. Born in Peru’s second largest city, Arequipa, in 1896, Vargas came to New York City in 1916 and had immediate success when Florenz Ziegfield, creator of the fabulous Follies, commissioned him to paint nearly twenty portraits for an exhibition at the Ziegfield opening in June 1916. The fee would be $200 for each portrait; they sealed this agreement by shaking hands. Vargas remained with Ziegfield until the Follies closed in 1931. He called the experience, “the most fantastic thing in my life. From then I was on my way.”

After the closing of the Follies, Vargas worked for a time in Hollywood but in 1939 was blackballed by all the studios for joining in a union walkout. In 1940, Vargas returned to New York City and began working for Esquire Magazine. After leaving Esquire, of course, he was to meet Hugh Hefner and go on to great success in the pages of Playboy Magazine.

The interview with Alberto Vargas took place by telephone on April 9, 1979. Mr. Vargas was at his home in West Los Angeles, California, and I was in New York City. An excellent recounting of Vargas’s life and work is Vargas by Alberto Vargas and Reid Austin (published by Harmony House).

CRAWFORD: You didn’t have a lawyer for the first or second contract?

VARGAS: No, I never had a lawyer. Do you know who my lawyer was? My right hand…

CRAWFORD: Tell me a little bit more about the lawsuit itself. You began to have some troubles with Esquire about the credit for the pictures?

VARGAS: Yes, first of all, he [the Esquire executive] said, “You know, Alberto, I like the work you’re doing, but we must do something about your name.”

I said, “What’s wrong with my name?”

He said, “It’s not phonetic. The Vargas Girl is no good, you have to drop the s.”

I didn’t know why he was doing this. I learned it later to my discomfort. I did the worst thing in the world to let him change my name…

CRAWFORD: Did he think you were getting too much money?

VARGAS: Yes…

CRAWFORD: How long did you go along doing this?

VARGAS: In 1946 he couldn’t stand it anymore. He had a backlog of about two hundred pictures, so he could go on for three or four years without me.

CRAWFORD: So he fired you at that point?

VARGAS: Yes.

CRAWFORD: Was it then that they started changing the name from Varga Girls to Esquire Girls?

VARGAS: Not only that. He began to cut the name in pieces. I couldn’t sign this, I couldn’t put the name Esquire in the circle of my name, the signature of my drawing. My wife and I were bewildered. We didn’t know what he was up to…

CRAWFORD: Then he took your name completely off the pictures?

VARGAS: Yes. He took it off entirely and called it the Esquire Girls…. [When my lawyer read the second contract] he said, “My God, you signed your death warrant.”

I said, “What do we do now?”

“Well, you have to fight now,” he answered. “You haven’t any money, but I’ll take it on the provision that if you get some, I get some. Otherwise I don’t see how to rescue you.”

CRAWFORD: Did you think that generous on the lawyer’s part?

VARGAS: Yes, he was honest, this lawyer, because he said, “He has put something on you that no man on earth can ever comply with. It said you are going to give him fifty pictures and he only had five. So you broke the contract,” that’s what he said. That I broke the contract for not producing fifty, only five. That was the whole thing…. He thought he had destroyed me then. But it wasn’t so, because we went and fought him. The lawyer went to work and he said, “There’s no way that I can do it, but I have to try at least.” But he [Esquire] had a slew of lawyers defending himself…

CRAWFORD: In what way did you win? What did the judge decide?

VARGAS: He decided that he [Esquire] had cheated me, that he had changed my name, that he had made up his mind to destroy me because no man on earth can have that—I don’t care what artist he had work at top speed. And he had three lawyers. I had none. [This refers to the suit for cancellation of the contract.]

CRAWFORD: But the decision that was finally published said that Esquire had won, because it said that in the United States there are no moral rights the way there are in Europe. Even though Esquire had taken your name off the work, they were not going to punish Esquire in any way…

VARGAS: The judge said, “This is a contractual matter. This has nothing to do with law. Nothing unlawful has been done to him. It is a contract that he has to live up to…” He [Esquire] saw the interest the other magazines had in me and he said, “My God, they are going to have what I just threw away.” Then he appealed…. He licked me also in the second court.

So I asked my attorney, “What can I do now? I cannot use my name. I have no money…”

“Oh, well, I tell you, Alberto,” [the lawyer answered], “you can go and dig ditches. That you can do without any name.”

CRAWFORD: He was being ironic?

VARGAS: Yes, purely. Then [the lawyer] was driving me to his home because his wife and my wife were waiting there for lunch when the decision came. And he was driving me and in the big yellow envelope was the decision. When we were six or seven blocks from the house, I said, “Do me a favor please. You go and give the bad news to Anna [Mrs. Vargas] and tell her that I’m coming later. I don’t want to face her. I don’t want to go and have to tell her, because this is awful.”

“And what are you going to do?” [the lawyer asked.]

“I’m going to kill that s.o.b.”

He said, “Are you kidding?”

I said, “Look in my eyes. Do you think I’m kidding?”

He said, “Don’t do anything foolish.”

I said, “That’s not foolish, that’s a pleasure. I got the idea just how to do it too…”

CRAWFORD: I’d like to thank you for this interview.

VARGAS: Will you send me your article on “Moral Rights and the Artist?” That is wonderful. Anytime that you need me, I would walk to Chicago or New York to help the cause because it’s my own…I want to help all the other artists. My time is passed already, but the newcomers are the ones that need a lot of help, believe me.

CRAWFORD: Thank you again.

VARGAS: The pleasure has been mine.

Right of Integrity

The artist’s right to object to any distortion, mutilation or alteration of art is known as the right of integrity. This right is illustrated by a leading French case involving six panels of a refrigerator painted by Bernard Buffet. It was Buffet’s intention that the refrigerator be exhibited as a whole. Accordingly, he signed only one of the six panels. Within six months of the first auction, however, one of the panels was offered for sale at a second auction under the description of a painting on metal by Buffet. He brought suit to prevent the sale of the panel separately and to have the entire work returned to him. In 1962, the court upheld him to the extent that it refused to allow the panels to be sold separately in either a public or private sale, but the private owner was allowed to keep the work. Buffet also received one franc as a symbolic vindication, the right to have the court’s decision published in three art journals of his choice at the defendant’s expense and the court costs.

On the other hand, prior to VARA, artists in the United States have not been notably successful in preventing the circulation and display of their work in altered or distorted form. Carl Andre, for example, lent a work to the Whitney Museum in New York City for its 1976 exhibition, “Two Hundred Years of American Sculpture.” Because the work was displayed near a bay window and a fire exit, Andre claimed these distractions distorted it and withdrew it from the exhibition. The Whitney Museum simply substituted another work by Andre from its permanent collection. Andre objected again, this time because the substitute work had been misinstalled by placing rubber backings under the copper floor pieces. He found, however, that he had no recourse against the owner of the work, whether the owner was a private person or an institution. While minimal art may test the understanding of courts, it would seem that an artist in Andre’s position today would be likely to be protected by VARA.

A recent case shows the interplay between VARA and state moral rights laws. Philip Pavia, an artist, sued defendants whom he claimed were improperly displaying his sculptural work. The work, titled The Ides of March and consisting of four separate parts, had been commissioned for a hotel but was later moved to a warehouse where only two of the four parts were displayed (Pavia v. 1120 Avenue of the Americas Associates, 901 F. Supp. 620). The court concluded that the sculpture’s four parts formed a single work that would be considered a “work of visual art” and therefore protected by VARA, but that VARA did not give the artist the right to stop post-enactment display of sculptural work mutilated before VARA’s enactment. On the other hand, VARA did not preempt the artist’s claim under the New York moral rights law for improper display of his sculpture occurring before VARA’s effective date and the artist’s allegations did state a claim under the New York law. In addition, the three-year limitations period applicable to artist’s claims under the New York law commenced to run each day the artist’s sculpture was improperly displayed in the commercial warehouse, rather than when the sculpture was first disassembled.

Destruction of Art

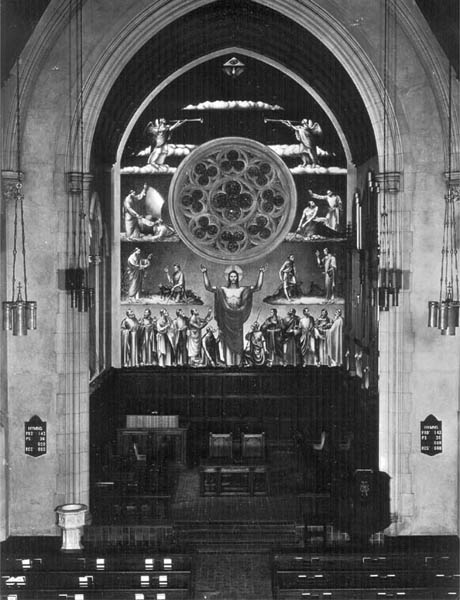

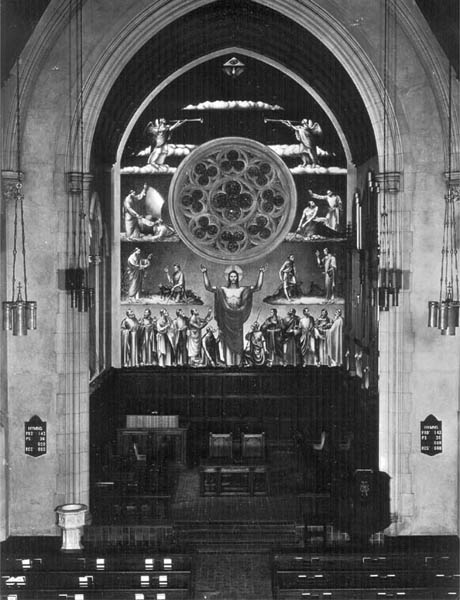

Prior to VARA, in the United States nothing prevented the owner of an artwork from destroying it completely. For example, in 1937, the muralist Alfred Crimi was selected by competition to create a fresco mural painting thirty-five by twenty-six feet for the Rutgers Presbyterian Church in New York City. The contract stated that the mural would be permanently affixed to the wall and that the church would also own the copyright. In 1938, Crimi completed the mural, but already some members of the congregation objected to it, complaining that the degree to which Christ’s chest was exposed emphasized his physical rather than his spiritual qualities. This protesting segment apparently increased so that in 1946 the mural was painted over in the course of redecorating the church. A black-and-white photograph of the mural is reproduced here.

Crimi sued, demanding that the mural either be restored, removed from the wall at the church’s expense and given to him, or that he receive an award of damages as compensation. The court held against Crimi, stating, “The time for the artist to have reserved any rights was when he and his attorney participated in the drawing of the contract with the church” (Crimi v. Rutgers Presbyterian Church, 194 Misc. 570, 89 N.Y.S. 2d 813). In the view of the court, the mural was merely property and could be destroyed at its owner’s whim.

Figure 10. Mural for the Rutgers Presbyterian Church by Alfred Crimi.

VARA would likely change the result if such a case arose today. If the artist and owner have not signed a written instrument stating that the work may be subject to destruction or mutilation by reason of removal, then the artist would have the right to prevent the mutilation of the work if the artist’s reputation would be damaged. The artist would also have the right to prevent total destruction if the work were of recognized quality. With respect to Crimi’s mural, there can be little doubt that the work would have been found to be of recognized quality. In addition to protecting art incorporated into buildings, VARA would also protect a privately displayed work from destruction if the work were of recognized quality.

Interview with Alfred Crimi

My interview with Alfred Crimi took place in his studio in Greenwich Village on February 3, 1979. He had contacted me more than a year earlier because of an article I had written on the subject of moral rights for American Artist. I stated that, “It is clear that in the United States nothing prevents the owner of an artwork from destroying it completely. For example, in 1937 a mural painter named Alfred Crimi was selected by competition to create a fresco mural painting thirty-five by twenty-six feet for the Rutgers Presbyterian Church in New York City…” Crimi’s letter chided me as follows: “I am Alfred Crimi who painted that fresco mural back in 1936, and so you touched a sore spot. [You say], ‘for example, in 1936 a mural painter named Alfred Crimi, etc.’-- you made it sound mythical and remote. I gather you are not acquainted with my status in the profession, except for what you have read in the law records. I can understand that. However, some research in the Who’s Who might have been appropriate. It behooves me, therefore, to identify and update myself from the remote to the living…”

Alfred Crimi looked far younger than his seventy-eight years. When we met he wore a white gown for painting and was neatly dressed in a black beret, grey flannel trousers, a pinstriped shirt, a sweater, and a bow tie. His manner was vigorous and, in addition to continuing to paint, he was writing his autobiography, which was published in 1987 and titled A Look Back–A Step Forward (The Center for Migration Studies, Staten Island, New York). He explained that he had achieved substantial success as a muralist, but had withdrawn from the world of galleries and dealers in 1959 so that he would not have to be a “peddler” as he pursued his own innovative “multidimensional” style (explained in his book, The Art of Abstract Dimensional Painting, published by Grumbacher Library). This withdrawal interested me, since it placed Crimi in the situation of many artists today, whether by choice or not, of pursuing art without connecting it to commerce. Crimi still felt the injustice of what had happened to his mural, and the interview began without my having to ask a question.

CRIMI:…Most of the traditionalist architects and archaeologists believe that a fresco is not good in the United States. It won’t hold out in the weather, in our climatic conditions. This was the challenge for me [in doing the mural at the Rutgers Presbyterian Church]…. So I would go every three or four months to check [the mural]. This time I was on vacation, it was right after the war and I spent a whole summer out of town in the country. I came back…and met a friend of mine I hadn’t seen in years…

He said, “By the way, do you know such and such a man?”—whose name I don’t remember.

“Why, what about him?” I said, “I don’t know him.”

“Well, he’s a member of the Board of Trustees of the Rutgers Church. He wants to know from me what kind of paints you used because they tried to wash it off and it won’t come out.”

So that put a bug in my head…I went up to Seventy-Second Street [on his way to visit his friend, the sculptor Carl Schmitz, in whose building he hoped to find a studio]. When I got there I decided to get off and I went to the Rutgers Church. For the first time they wouldn’t let me in.

CRAWFORD: Who was there?

CRIMI: The sexton.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Crimi,” [he said], “We’ve been given orders not to allow anybody in the church.”

I said, “Well, can I see Dr. Russell?”—who was the minister.

He said, “Dr. Russell had retired.”

I said, “Well, who is the minister now?”

I said, “Can I see Dr. Key?”

“Well, I’ll go upstairs and see.”

Dr. Key naturally had to be gracious and receive me. He said, “I’m very sorry, Mr. Crimi, the mural has been painted over.”

“What?” I said. I couldn’t believe it. “Painted over. What for?”

He said, “Well, the main objection was the nakedness of the chest of Christ.”

I said, “You mean to say in the twentieth century they are so prudish? Even if he were naked, you could have called me and advised me and I could have done something about it. But instead you destroyed the mural. It’s an offense to me, because you are destroying my name which is there…. May I see the mural?”

He said, “I’m sorry, Mr. Crimi, but we cannot allow anybody there until the decorations are over.”

So naturally I went over to him and said, “I want to see under what shroud you buried this corpse.”

[Crimi went to see Carl Schmidt. They contacted Dr. Frankfurter, the editor for Art News, who suggested they obtain an injunction to prevent the Church from going ahead with its destruction of the mural. Press coverage was highly favorable to Crimi throughout his struggle to save the mural. Carl Schmitz helped Crimi find a lawyer, Milton Morrison, to take the case.]

CRAWFORD: How did he take the case? CRIMI: Without any charge. He thought the case was a rare case, an unusual case, and he took it.

CRAWFORD: What was his background as a lawyer? What kind of cases did he usually handle?

CRIMI: I have no idea. I was green myself. I was a babe in the woods, you see. I was grown up but I didn’t know anything about legality. And I wasn’t looking for trouble so I was unprepared for anything like that…

CRAWFORD: After what has been done to the mural, can it be restored?

CRIMI: I don’t know. It might be possible with an oil detergent, but it would be a very delicate operation because of the coat of aluminum bronze.

[Crimi said that the mural itself was to be a last gesture by Dr. Russell as a surprise for the parish before he retired. In discussing the history of how he was chosen to paint the mural, Crimi explained that he won an open competition sponsored by the National Society of Mural Painters in 1936 for the commission to do the mural. After he won the competition, he met all twenty or twenty-five of the Church’s Board of Trustees and the five or six members of the Decorations Committee to discuss his sketches for the mural. He pointed to the photograph of the mural as he recapitulated to me his explanation of the mural’s imagery.]

…I have a triangle here which is the Trinity. And the all-seeing eye, an old Egyptian symbol that was taken over by the Christians. And this is the Holy Ghost, the dove.

Now there was a lady there, one of the officer’s wives. And she said, “Mr. Crimi, is this a Communist symbol?”

[The woman pointed to the all-seeing eye. Crimi told them to look on the Church’s baptismal fountain where the same symbol appeared. This demonstration that it was not a Communist symbol cleared the way for his work to begin. But it also showed a bias against the mural that certain of the officers felt from the start of the project. Dr. Russell, who supported Crimi and the mural, wrote on September 18, 1946 to Crimi that:

I did everything in my power to prevent what has happened, but what I could do was practically nothing as the committee took council with no one and none save the committee know even now what is to go on the wall.…I am sorry beyond words that you have been so hurt. I’ve been hurt quite a lot myself. I try to remember One who said: `Father forgive them for they know not what they do.’” [Dr. Russell died of a heart attack three months after writing this letter.]

CRIMI: When I went back to the Church with my lawyer, we had a meeting with their lawyer. Their lawyer must have been an Irish Catholic. He didn’t know anything about it. He said, “Mr. Crimi, what is the problem?” And I told him that I was told that because of the nakedness of the chest of Christ, they had destroyed the mural. He said, “Oh, no, Mr. Crimi, that isn’t it. If you know the background of the Presbyterians, they don’t believe in murals.”

“The Presbyterians wanted the mural,” [I replied], “Why don’t they believe in it now? This is a contradiction.”

Then Mr. Etherington, the culprit [the President of the Board of Trustees], came to the rescue and he said, “Mr. Crimi, that isn’t it. To be honest, Dr. Key said that the mural interfered with his work during services.”

CRAWFORD: How could it have done that?

CRIMI: He was a poor speaker to begin with and the acoustics were not so very good.…So that the people were looking at the mural instead of listening to his sermons.… Now, when we sued, we didn’t sue for money. We sued for moral rights.… Eventually we also had to sue for money. That’s as far as the Church controversy got until we went to court.

CRAWFORD: There were no more negotiations? In other words, it has been painted over and after your meeting with the Church’s lawyer you had to sue?

CRIMI: That’s right…

CRAWFORD: Were you represented by a lawyer when you signed the contract to do the mural in 1936?

CRIMI: I had no lawyer, the Church had a lawyer when the contract was signed. And he really manifested the prejudice that had already been created. [Crimi’s statement contradicts the court’s decision referring to Crimi “and his attorney.” I checked this important point again with Crimi who assured me that he did not have a lawyer represent him when he signed the contract.] CRAWFORD: How would you describe the nature of the congregation in 1936?

CRIMI: Hypocritical…

CRAWFORD: These were well-to-do people?

CRIMI: Yes…

CRAWFORD: Can you describe the trial?

CRIMI: The judge was retired and they called him in for this case. The judge was very much interested in this case. And he was like a young boy. He got up from the bench and he came down and he fed the slides into the projector himself. I could see that his attitude was all for the artist. At the end…he asked the two lawyers to come into his chambers. In the chambers he told the lawyers to come to some settlement. If the judge said, “Come to some settlement,” he must have seen that I had some rights to be settled, otherwise he wouldn’t have said it. But the other lawyer stuck to the letter of the law. He didn’t have any compassion for the artist at all. And I think this is a damnation throughout the history of art in America and will continue to be.

CRAWFORD: So there were no settlement offers made at any time?

CRIMI: None. Then I got disgusted. You see, we didn’t believe it would ever go on the calendar at all, because my lawyer knew the law.…Our intention was to create enough publicity that…it would get support… [After losing the case, Crimi said that he couldn’t appeal because he had no money and didn’t feel he could ask the lawyer to continue working for free.]

CRAWFORD: But you wanted to present a bill in Washington?

CRIMI: Yes, we wanted to do that.… It was my own experience. I thought there should be a bill for the profession…and I believe there should be a bill for the profession on the inheritance tax…but I’m sort of a loner. I don’t participate anymore, since the 1950s. In 1959 I withdrew from the rat race on Madison Avenue. I haven’t given a one-man show on Madison Avenue since 1959.

CRAWFORD: What prompted you to make that decision?

CRIMI: Because I know that they’re a bunch of crooks. They are opportunists. They treat an artist like a peddler. An artist is not a peddler, he’s someone who anticipates the future…

CRAWFORD: When you withdrew from the art world, did you feel a kind of freedom?

CRIMI: Yes, because I’ve been painting to please myself. I never paint a picture on commission, unless it’s a mural. I never paint to sell. My paintings are good or bad or indifferent. They are an expression of myself. I believe it’s a sincere expression. It’s not for the public to judge…

CRAWFORD: In 1946, when you found out what was going on, did other artists rally to support you?

CRIMI: In the beginning, some of them did.

[Crimi relates that the Salmagundi Club membership wanted to support him, but were dissuaded by a lawyer member. Instead of taking a moral position, they followed the lawyer’s strictly legalistic conclusion that Crimi had no chance to win in court. At the beginning, he received support from the National Society of Mural Painters, but they withdrew their backing from fear of preventing other churches from having murals painted. After this support ended, the National Sculptors Society and other artists’ groups also fell silent. Only the editors of the arts magazines gave unstinting support to Crimi throughout his struggle.]

CRAWFORD: What happened after the lawsuit was over and the publicity had quieted down?

CRIMI: Every now and then there was an article…on artist’s rights… But I was glad that I did sue them, because if I hadn’t I would never touch a brush again. I was so frustrated…

CRAWFORD: What do you feel is the lesson for people, artists today, who are thinking about moral rights and these kinds of issues to draw from your own experience?

CRIMI: I blame the artists because they’re not willing to fight for their rights.

In November 1988, the newsletter of the Rutgers Presbyterian Church ran a lengthy article about the dispute and excerpted from one of my essays about its battle with Crimi. The article, accompanied by photographs of the mural and Alfred Crimi, concluded, “Was it really only a ‘tempest in a teapot’ or a valid moral rights case? You be the judge.” If this was some vindication of Crimi and his mural, the best vindication was to come in 1991 with the passage of VARA. Crimi had testified in favor of both the New York State moral rights law and the federal legislation that ultimately became VARA. Senator Kennedy praised Crimi, a courageous pioneer whose legal struggle helped point the way toward the legislation needed to improve the rights of artists.

A Test of VARA

The protections offered artists by VARA with respect to the destruction of art were the focus of Carter et. al. v. Helmsley-Spear (71 F.3d 77, cert. denied, 517 U.S. 1208). Three artists worked under contract to create an environmental sculpture permanently affixed to the defendant’s building. When the defendant decided that it wanted to remove or destroy the art, the artists brought a lawsuit seeking a preliminary injunction to protect the work.

In creating the art the artists worked under contract with the defendant, though the defendant argued that the artists had done work-for-hire. In support of this, the defendant offered proof that it “provided plaintiffs with some tools, required that plaintiffs work on the Work for a minimum number of hours weekly, paid plaintiffs via a weekly check, paid some of plaintiff’s assistants, provided plaintiffs with some health insurance benefits for a portion of the time they worked on the Work, and withheld taxes from weekly checks issued to plaintiffs.” However, while the federal District Court concluded that the work was not for hire, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed due to its determination that the defendant had correctly defined the relationship as work for hire. While this narrow determination removed the art from the protection of VARA, it is worthwhile to follow the reasoning of the District Court since such reasoning is likely to apply to similar cases in the future when the artists are clearly not employees of the commissioning party.

The district court made a factual finding that the art was installed in the building in such a way that it would be destroyed if it were removed. This led to the issue of whether the art was a work of recognized stature under VARA, and whether its destruction would be prejudicial to the honor or reputation of the artists. Several experts testified in the artists’ favor on these points, leading the court to decide that serious issues existed that would make the artists’ claims worthy of being litigated. The existence of such serious issues is a threshold test in the granting of a preliminary injunction.

Next the court concluded that defendant’s arguments against the constitutionality of VARA—primarily on the ground that VARA allows an unconstitutional taking of property interests—were not likely to succeed. So the court granted a preliminary injunction to the artists to prevent the destruction or removal of the art.

However, the decision of the Court of Appeals makes the reasoning of the district court merely instructive rather than dispositive. Barring subsequent appeals by the artists, it appears that a landmark interpretation of VARA will have to wait for a future case.

Two interesting cases have been decided in the wake of the Carter decision. In Martin v. City of Indianapolis (982 F. Supp. 625), the court found a violation of VARA when the city contracted to have a stainless steel sculpture destroyed after acquiring the land on which it was located. Because the art was created on the artist’s own time as a personal project, the court determined that the sculpture was not work for hire subject to exclusion from the protection of VARA. The court also held that, although the sculpture was completed four years before VARA became effective, it was still protected because the artist established that he maintained title during the time between completion and enactment of VARA and beyond the effective date of VARA.

In the second case, English v. BFC & R East 11th Street LLC (1997 WL 746444), a group of six artists had created artwork in a community garden on East 11th Street in New York City. The artwork consisted of approximately five murals and five sculptures that the artists saw as a single work of art. The artists described the garden as “a large environmental sculpture encompassing the entire site and comprised of thematically interrelated paintings, murals, and individual sculptures of concrete, stone, wood, metal, and plants.” The lot, however, was owned by the City and was sold for development in May of 1997. The artists, hoping to stop the development and protect the sculpture garden, brought this action.

The court, in refusing to extend VARA’s protection to the works in question, held that moral rights encompasses two specific rights: integrity and attribution. Integrity is at issue here because the critical determination is whether the garden in question should be conceived as a single work of visual art, hence falling within the scope of VARA, or whether each mural and sculpture should be seen as an independent work and therefore not fall within VARA’s scope, as each work could be moved without being physically destroyed or mutilated. The court held the works to be independent and therefore not protected under VARA. Perhaps most importantly, the court held that VARA does not apply to artwork that is illegally placed on the property of others without their consent, when such artwork cannot be removed from the site in question.

Yet, even when an artist creates work at the behest of a property owner, courts are reluctant to treat the location of the work as inherent to the overall integrity of the art. In other words, relocating a sculpture or mural does not trigger VARA protections, even if the artist insists that the location is essential to appreciating the work. One case that illustrates this point is Phillips v. Pembroke Real Estate (459 F.3d 128). In that case, David Phillips, a sculptor well known for his “environmental” sculpture, tried to prevent a developer from moving his artwork. Phillips’s sculptures were part of Boston’s Eastport Park, and were deeply interwoven into the overall layout and structure of that park. In 2003, Pembroke Real Estate sought to totally redesign the park layout, and their plans called for moving a number of Phillips’s sculptures. Phillips sought an injunction, arguing that the location of the sculptures was an important element of the overall work, and that any attempt to shift or move the pieces would violate his rights of artistic integrity as protected by VARA. The court of appeals rejected this argument, however, holding that VARA did not protect the “site specific” quality of a particular work. Similarly, the Massachusetts State Court also held that Massachusetts’ moral rights protections did not protect the site-specific character of an artist’s work. These holdings reaffirm a pre-VARA decision in which a separate federal appellate court refused to recognize any right to artistic integrity in the particular location of an “environmental” sculpture. See Serra v. United States General Administration, 847 F.2d 1045 (2d Cir. 1988). Hence, while VARA may protect individual, standalone pieces from mutilation, alteration, or destruction, it does not protect the artist’s right to have those works remain in any particular place.

Right of Disclosure

In France, the moral right of disclosure gives the artist sole power to determine when a work is completed and ready to be disclosed to the public. This has led to some interesting decisions in French courts. In the Whistler case in 1900, the artist was dissatisfied with a portrait he had done on commission. Lord Eden, who had commissioned the portrait, was satisfied and demanded delivery of the work. Application of the right of disclosure gave Whistler the right not to deliver the work until such time as he considered the work completed, despite the fact that the work had been publicly exhibited. The Camoin case in 1931 involved a painter who had slashed and discarded several canvases. The slashed canvases were found and restored by another person who sought to sell the works. The painter intervened, based upon his right of disclosure, and the French court seized and destroyed the canvases in accordance with the artist’s original intent.

The Rouault case in 1947 was a dispute between the artist and the heirs of the artist’s dealer. The artist had left 806 unfinished canvases in a studio in a gallery of the dealer. Rouault, who had a key to the room and would occasionally work on the paintings, had agreed to turn over all his work as created to the dealer. The dealer died and the heirs of the dealer claimed to own the 806 works. The court held that Rouault owned the works, because the right of disclosure required the artist himself determine the work to be completed before any disclosure of the work to the public by sale could occur. Any agreement to the contrary would be invalid. Finally, the Bonnard case ultimately resolved that paintings only become community property upon completion to the artist’s satisfaction. The estate of an artist’s wife would, therefore, have no right in works the artist had chosen not to disclose. The right of disclosure, like the other moral rights, was enacted as legislation in France on March 11, 1957.

VARA does not deal with the moral right of disclosure. While it may be argued that our copyright laws provide similar protection, it is not clear that copyright or other laws would, for example, protect unfinished artworks from the demands of a bankrupt artist’s creditors or from a spouse in divorce proceedings in a community property state.

Duration and Enforcement

Moral rights in a country such as France are perpetual. If the moral rights are perpetual, the question arises who will enforce such rights after the artist’s death. In France, the right of disclosure is enforced by the artist’s executors, descendants, spouse, other heirs, general legatees and finally by the courts. The rights of attribution and integrity can be transmitted to heirs or third parties under the artist’s will for enforcement.

VARA is an amendment to the copyright law, which provides for damages, injunctions, court costs, and attorney’s fees if a copyright infringement claim is successfully prosecuted. However, the criminal penalties that can be visited upon a copyright infringement defendant are not available to punish those who violate an artist’s moral rights. VARA also provides that copyright registration need not be made by an artist in order to bring a lawsuit for the violation of moral rights. In addition, registration prior to the violation is not required for the artist to be eligible for an award of attorney’s fees or statutory damages in a moral rights case.

State Moral Rights Laws

Prior to the enactment of VARA, a number of states pioneered by enacting their own moral rights statutes. While the copyright law preempts state laws that cover the same subject matter, certain aspects of the state laws that are beyond the scope of VARA will presumably be found to remain in force. There are now eleven states with moral rights laws in force: California, Connecticut, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island. Utah has enacted moral rights for works commissioned under its percent-for-art law. These state laws tend to be modeled on either the moral rights laws in California or New York.

Moral Rights in California

Former State Senator Alan Sieroty acted as a great friend to artists in California. He sponsored almost all of the art legislation that has made California the preeminent state in protecting its artists. His sagacity and concern for the artist is evidenced by the Art Preservation Act that he guided to passage in 1979 and which took effect on January 1, 1980.

The law protects, “…an original painting, sculpture, or drawing, or an original work of art in glass, of recognized quality, but shall not include work prepared under contract for commercial use by its purchaser.” The fine artist is protected by this law, but the commercial artist is not. Under the California law, art is recognized to have quality based “…on the opinions of artists, art dealers, collectors of fine art, curators of art museums, and other persons involved with the creation or marketing of fine art.” Presumably a similar determination will be made as to recognized quality for purposes of VARA.

California does not focus its protection on the artist, but protects art of a certain quality. Thus, the law does not necessarily connect the artist to his or her art, but instead preserves for society certain pieces of art that have an agreed-upon significance.

Only an artist may alter, deface or destroy his or her art (provided, of course, that not even the artist may do this unless he or she owns the art). The artist retains, “… at all times the right to claim authorship, or, for a just and valid reason, to disclaim authorship of his or her work of fine art.” However, the California law allows the artist to waive these moral rights by an express written instrument signed by the artist.

The protections in the law last for the artist’s life plus fifty years. After the artist’s death, these rights may be enforced by the artist’s heir, legatee or personal representative. (such as an executor or administrator).

A special provision of the law deals with art affixed to buildings. If the owner of the building intends to remove art that can be removed without substantial harm, the artist has rights to the art if the owner intends to alter, deface, or destroy it. In such a case, the owner would have to make a diligent effort to give notice or actually give written notice of the planned removal to the artist or the artist’s successor-in-interest. If the artist fails within ninety days of receipt of notice to remove the art at the artist’s own expense, the owner may alter, deface, or destroy it. An artist who removes or pays to remove art from a building in this situation becomes the owner of the art.

On the other hand, if substantial harm will of necessity be caused to the art by its removal, the artist must obtain a written instrument signed by the owner of the building and providing for the protection of the art. This instrument must be recorded, presumably in a registry where other real estate documents such as deeds would be recorded, in order to be binding. Otherwise the artist will have no rights in the art and it may be destroyed by the owner.

An action under the law must be brought within the longer of either three years from the act complained of, or one year from the artist’s discovering that act.

The artist’s remedies include injunctive relief, actual damages, punitive damages, reasonable attorneys’ and expert witness fees, and such other relief as the court considers appropriate. Since punitive damages are awarded to punish wrongful acts rather than compensate the artist, any punitive damages awarded under the law are paid to an organization selected by the court to be used for charitable or educational activities involving the arts in California.

The California law appears to be preempted in large part by VARA. However, a crucial aspect that ought not be preempted is the extra fifty years of protection afforded by the California law, since its term is life plus fifty years while VARA’s term is, in general, only the life of the artist. It is instructive to contrast the provisions of the California law with those of the New York law described in the next section.

Moral Rights in New York

On January 1, 1984, a landmark law benefiting artists took effect in New York State. Due to the passage of VARA, an issue now exists as to whether or to what degree the New York law may have been preempted by the passage of VARA. One case, Board of Managers of Soho International Arts Condominium v. City of New York (2003 WL 21403333), held that the New York law is preempted, but this decision is controversial. For VARA to preempt a state moral rights law, the rights granted in that law must be the same or equivalent to the rights granted in VARA. As the court observed in the Pavia case, “[W]hether the rights conferred by VARA are equivalent to those of [New York’s moral rights statute] will occupy courts for years to come.” In view of this, it is interesting to explore the history and scope of the New York law, especially the ways in which the statute is more extensive than VARA and therefore should not be preempted. The following discussion assumes that at least some parts of the New York law are not preempted.

Sponsored by Assembly Majority Leader Richard Gottfried and known as the Artists’ Authorship Rights Act, this law entitles artists to name credit when their work is displayed or reproduced and protects artists against alterations or mutilations of their work (but not against complete destruction). Working closely together, the Assembly’s Committee on Tourism, Arts and Sports Development, the Graphic Artists Guild, and the American Society of Magazine Photographers brought about the passage of the law. As the main author (along with Wendy Feuer of the Committee’s staff) of the original draft of the New York bill, I sought to broaden the scope of protection to include reproductions of art, photography, and design, even if these reproductions were prepared under a contract for commercial use. After much lobbying and numerous revisions, the New York law protects “any original work of visual or graphic art of any medium,” including reproductions of such art. However, the law does not protect works prepared under contract for advertising or trade use. Thus, the art or photography for a point of purchase display or product packaging would not be protected. Art prepared for magazines, books, and other public interest uses would be covered.

No one, other than the artist or a person acting with the artist’s permission, may publish or display an original work or a reproduction in an altered or defaced form if damage to the artist’s reputation is reasonably likely to occur. If a violation takes place, the artist has the right to have his or her name removed from the work. If a work is published without the artist’s name, the artist has the right to insist that his or her name accompany the work.

By protecting the reputation of the artist, the law protects the integrity of the art itself. Cropping for publication will undoubtedly become an issue. Is the cropping done in such a way that damage to the artist’s reputation is reasonably likely to result? This test is flexible, so that unobjectionable cropping can continue. However, if a user fears that cropping or other alteration might damage the artist’s reputation, it would be best to obtain permission from the artist for the form of the image to be disseminated. Other changes in the art, such as additions or deletions to the image, may risk violating the law and require the precaution of obtaining the artist’s consent.

The law’s name credit provisions would have affected the result of the famous Esquire v. Vargas case. Under the law in New York, Vargas would have had a much better chance to win his case. The law does not appear to permit a waiver by the artist of the right to claim or disclaim authorship credit, since it states, “…the artist shall retain at all times the right to claim authorship or, for just and valid reasons, to disclaim authorship of his or her work of fine art.”

A limitation in the law provides that, “a change that is an ordinary result of the medium of reproduction does not by itself create a violation.….” For example, a reproduction of a painting that appears in a magazine will not be identical to the painting itself, but the law will not be violated if the alterations are those that ordinarily accompany such a change of medium. At what point changes are no longer “ordinary” will have to be decided on a case-by-case basis.

The law does not apply unless a work is “knowingly displayed in a place accessible to the public, published or reproduced in this state.” The work must be made public before a violation occurs. A painting defaced in a private home or an unprinted template or layout file containing an altered image are not violations until the work reaches the public. Also, a person who does not know an image has been altered will not be liable for making it public, since the violation would not have been done “knowingly.”

The law applies to any work published or displayed in New York. However, the true impact of the law is national. Since most published works eventually are sold in New York, the law will undoubtedly affect publishers in other states. Compliance with the law will be a necessity for publishers who plan to market in New York.

For original art, conservation is not a violation of the law unless it is done negligently. Also, changes caused to originals by “the passage of time or the inherent nature of the materials” will not be a violation of the law, unless such changes were the result of gross negligence in protecting or maintaining the art. Gross negligence is an intentional failure to perform a required duty with utter disregard for the consequences.

The protection of the law lasts for the artist’s lifetime. The right is personal to the artist, who is the only person who may sue to rectify violations. Any lawsuit must be brought within three years after the violation occurs or within one year after the artist should have found out about the violation, if that would be a longer time period.

If an artist’s rights have been violated under the law, he or she may sue for damages. The amount of the damages will be based on the nature of the injury suffered. Expert testimony about the significance of a good and growing reputation for success in the field will probably aid in establishing the amount of damages. The law allows for a suit to prevent a potential violation from taking place as well as to prevent any existing violation from continuing.

The New York law is preempted in large part by VARA. However, the New York law protects art in books, magazines, and other public interest uses, while VARA does not extend to published works. So with respect to these and other rights not similar to those protected by VARA, the New York law may continue in force and extend the scope of protection provided by VARA.

The fact that so many states enacted moral rights laws suggests the wisdom of VARA, which will ensure uniformity of treatment (except insofar as some parts of the state statutes are not preempted by VARA). In addition to rights granted by VARA, the artist in the United States can also seek additional protection by the use of avenues such as unfair competition, trademarks, trade dress, the right to privacy, protection against defamation, the right to publicity, and patents. Each of these is considered separately in the next chapter.