15 SALES OF REPRODUCTION RIGHTS

Commercial artists earn their livelihood by selling reproduction rights to clients. The art is often created on assignment for the client. Nonetheless, the artist will own the copyright (unless the assignment is work-for-hire) and the original art. What rights will the artist transfer to the client and what contractual protections will the artist require?

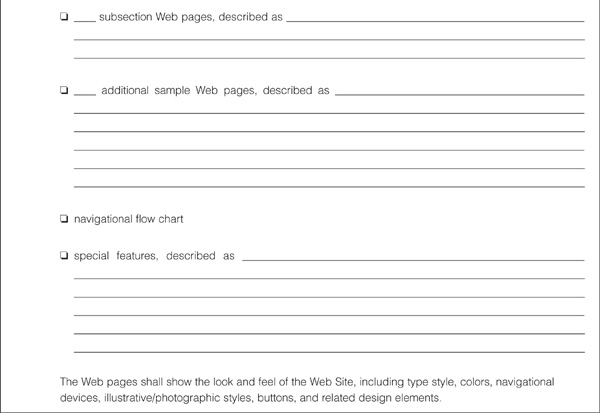

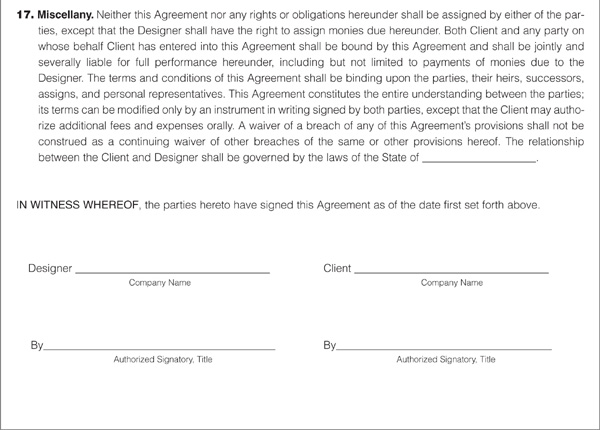

The artists’ professional organizations have created model forms for use in selling reproduction rights. This chapter includes model forms for photographers, illustrators, graphic designers, and textile designers that can be adapted to sell art to any market. In addition, syndication and other forms of commercial exploitation are covered. A contract for Web site design is also included. Sophisticated contracts for the sale of reproduction rights include the book publishing contract discussed in chapter 16, the video broadcast agreement discussed in chapter 17, and the multimedia contracts discussed in chapter 18.

Battle of the Forms

One pitfall to be avoided is the oft-encountered battle of the forms. An art director sends a purchase order that has one set of terms. The artist sends back a confirming letter (or form) with different terms, but starts work immediately because the assignment is on a deadline. When the assignment is billed, the artist’s invoice follows the terms of the confirming letter. But the client’s check has terms stamped on the back that conform to the terms of the client’s original purchase order. When all is said and done, neither party knows the actual terms of the transaction.

As the chapter on contracts pointed out, agreement must be two-sided. The moment a potential disagreement arises, the artist must deal with it. If a purchase order has unacceptable terms, it becomes especially important to obtain a signed contract with terms acceptable to both parties (or a client’s response accepting the terms of the confirmation form). If deadlines are tight, faxes or overnight delivery services can be used to speed the reaching of agreement. To continue working when agreement has not been reached is to invite disputes.

Such disputes can be avoided by using the model contracts at the end of the chapter, all of which cover certain basic terms.

Assignment Description and Due Date

There must be a description of the assignment and a due date. If the client is to provide reference material or take other steps that are necessary for the artist to perform, any delay caused by the client should extend the artist’s time for performance.

Fee

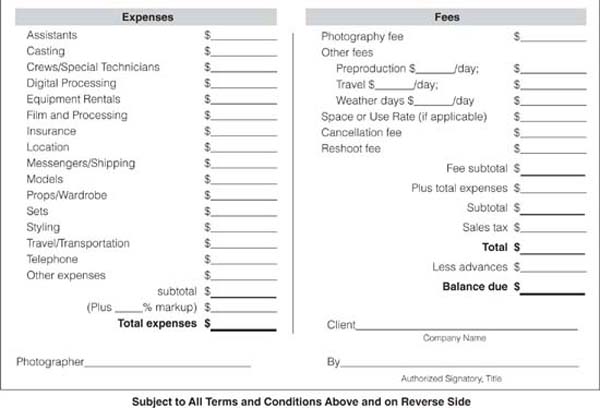

A basic fee should be specified for the assignment. For photography this might be a day, shot, or hourly rate, in which case any minimum guarantee as to the amount of time or number of shots should be specified. Alternatively, event photographers may charge by the event, estimating the price for all on-site and post processing work in advance. For sales to magazines the day rate will normally be an advance against the space rate in the magazine. For an advertising assignment, usage fees may be paid in addition to the day rate if a number of images are used, and sometimes even if a single image is used.

If work beyond the original assignment is required, such as overtime on a shoot for which the fee is modest or many additional sketches on an illustration, an hourly rate or per sketch fee may sometimes be agreed upon. Days spent on travel and preparation should be compensated, as should days on which it is impossible to work due to the weather, if that is relevant. Travel and weather days may be paid for at half the regular day rate, although this is negotiable. Payment for extensive amounts of preparation time is also becoming more common.

The surface/textile designer estimate and confirmation form provides a breakdown of estimated prices for different categories of work.

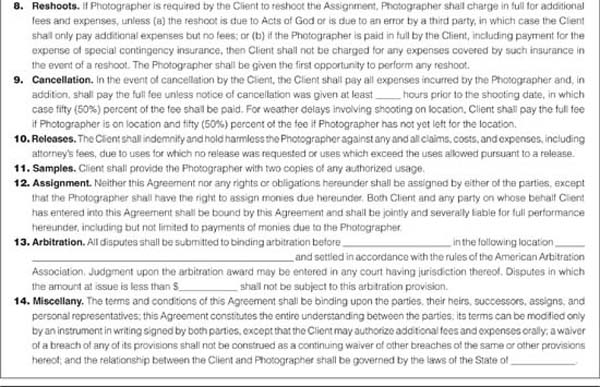

Cancellations

If an assignment is canceled, a cancellation fee should be paid. A cancellation fee is often referred to as a “kill fee,” though some artists consider “kill fee” to be pejorative, since it may reflect on the artist’s work. Of course some assignments are canceled prior to work even commencing. In this case, it is unusual to receive a cancellation fee, except that photographers may negotiate for such a fee if reasonable notice (such as forty-eight hours) of the cancellation is not given prior to the time the assignment was to start.

The contract for graphic designers requires payment for cancellation based on the contract price in relation to the degree of completion of the work, while the illustrators’ contract allows the filling in of percentages to be paid if cancellation is after sketches (perhaps 25 to 50 percent of the fee) or finishes (perhaps 50 to 100 percent of the fee). If the cancellation is due to dissatisfaction with the art, the fee will usually be lower than if the cancellation is for reasons unrelated to the art (such as a decision not to do the project).

In the event of cancellation, the artist would seek to retain the rights in the art that has been created. Cancellation implies that the client has no use for that art, so retention of the rights by the artist appears reasonable.

Usage

The fee is often based on usage. This makes it important to specify what use of the art is anticipated. The photographer’s contract does this by specifying category, media, and title. The contractual terms then give the following definitions: “‘Category’ means advertising, corporate, editorial, etc.; ‘Media’ means brochure, magazine, hardcover book, billboard, etc.; ‘Title’ means publication or product name.” By carefully limiting usage to the client’s needs at the time of entering into the contract, the fee can then be based on that usage. If the client later wishes to make greater usage, reuse fees can be agreed on (if such fees are not specified in the original contract).

The illustrator’s estimate and confirmation form limits usage in the same way, as does the graphic designers’ contract. However, these contracts contain additional limitations, since the geographic area of use, the time period of use, number of uses or the edition of a book can also be specified.

Most magazines purchase only first North American serial rights (sometimes called first rights), the right to be the first magazine to publish the work in North America. After such publication, the artist is free to sell the work elsewhere. A variation of first serial rights would be first North American serial rights, whereby the artist conveys to the client the right to be the first magazine publisher of the work in North America. Another grant of rights would be second serial rights—the right to publish artwork that has appeared elsewhere. A different grant of rights would be one-time rights—the right to use the work once but not necessarily first and certainly not exclusively. Another way of expressing this could be the grant of simultaneous rights: granting the right to publish to several magazines at once.

The artist should keep in mind the possibility of limiting the grant of rights with regard to exclusivity, types of uses, duration, and geographical scope. The artist who wishes can define exactly the nature of the permitted publication. If possible, the artist should avoid selling all rights (sometimes called exclusive world rights in perpetuity), which would mean the artist retained no rights to the work. Prior to 1978, magazines sometimes purchased all rights with the understanding that certain rights would be transferred back to the artist after publication. In such a case, the artist should have had a written contract setting forth precisely which rights the magazine would transfer back to the artist. Since 1978, this trust arrangement has become obsolete because contributions are protected by the magazine’s copyright notice (although it is best to have copyright notice for the contribution in the artist’s name).

The surface/textile designer’s estimate and confirmation form leaves the limitation of rights to be filled in under special comments, but the approach to limiting rights is the same as in the other contracts.

It is important to state that only the specified usage is granted to the client. A more formal approach would be to recite, “All rights not hereby transferred are reserved to the Artist.” Usage should also be limited to images actually purchased. Many photographers, for example, profit by using out takes from assignments to create stock files for sale. This is an accepted practice as long as the photographer does not sell the outtakes to a company competitive with the original client.

Electronic Rights

Electronic rights cover many of the ways in which images will almost certainly be marketed in the future. The ability to digitize images, store vast numbers of images, and deliver such images into homes and offices around the world is part of the electronic revolution. While multimedia contracts are discussed in chapter 18, the artist working for print or other nonelectronic media should not sell electronic rights. The value of these rights can be difficult to determine, since this is a rapidly evolving frontier. Nonetheless, the growth of the Internet makes it especially important to retain rights to profit from it. As with any right the client does not intend to use, and therefore is unlikely to be paying for, the artist should reserve electronic rights to him-or herself. Conversely, if electronic rights are being licensed, nonelectronic rights should be reserved to the artist. In addition, the nature of the electronic license should be carefully spelled out as to type of use, medium of use, duration of use, territory, and similar limitations. The artist should try to negotiate out of any contractual provision that seeks rights in media that don’t as yet exist but may be discovered in the future.

Advances and Expenses

Photographers and designers are paid for their expenses as a routine matter. An issue arises as to whether these expenses should be marked up. For example, should a 15 or 20 percent charge be added to the expenses when billing the client? The justification for such a charge is the bookkeeping cost involved, the overhead expense to make such outlays on behalf of the client, and the cost (in lost interest) of paying money for the client and then having to wait to be reimbursed. There is no general rule, but some photographers and virtually all designers markup expenses when billing the client.

Illustrators often do not bill for expenses because the expenses are minimal. If such expenses are not minimal, the illustrator is certainly justified in requesting a reimbursement (perhaps, for example, if the assignment requires hiring a model).

Sometimes, an advance against expenses can be negotiated. Such an advance provides part or all of the money estimated for the expenses. When an advance is paid, the justification for marking up expenses is lessened. The artist is no longer in effect lending money to the client, although extra overhead costs are still incurred in keeping track of the expenses and billing them to the client.

Changes and Reshoots

If changes are necessary, the artist should be given the first opportunity to make such changes. If the changes are due to a change in the assignment, of course, additional fees should be paid. Likewise, a reshoot might be done on the basis of expenses plus half the regular fee when the client changes the assignment.

Authorship Credit and Copyright Notice

The contracts provide for such credit when the use of the art is editorial (such as for magazines or books). If the art is for corporate or advertising use, authorship credit is less common and would have to be added into the contract form.

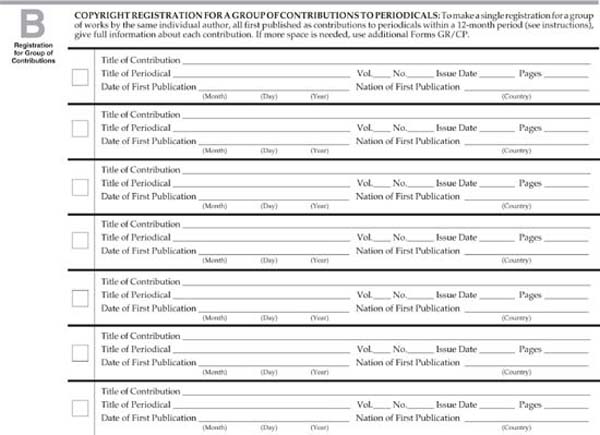

Copyright notice does not accompany art unless the artist requires such notice. Often the name credit can simply be elaborated by adding the copyright symbol and the year date. A common mistake in magazines had been a photograph with a copyright notice that lacked the year date. Such a notice would have been acceptable prior to 1978, but from January 1, 1978, until March 1, 1989, a notice lacking a date was the same as no notice as all. Of course, the notice in the front of the magazine protected all contributions (except for advertisements, which require their own notice), but the photographer’s protection was reduced because a person who received a license from the magazine to use the photograph would have a defense against the photographer (who would be able to collect from the magazine).

After March 1, 1989, no copyright notice is required, so a copyright notice without a year date should not present any problems. Copyright notice in the name of the magazine will protect contributions in the sense that innocent infringers will not be eligible to ask for mitigation of damages due to the infringer’s reliance on the absence of copyright notice for a contribution. In addition, the infringer’s having obtained a license from the magazine in reliance on the absence of copyright notice with the contribution will no longer be a defense.

Return of Originals and Samples

Original art should be specified to remain the property of the artist. After the art has been used for reproduction, it should be returned to the artist. If clients expect to keep originals and are paying a sufficient fee, this should be stated. For photography, the client may expect to keep shots that are used, but not outtakes. Stock sales for photographers and sales of originals for illustrators depend on the proper retention of ownership of rights and art. These can provide yet another source of residual income (in addition to reuses by the client beyond the usage originally agreed on and paid for). Also, if art is never used by the client, the contract may specify that after a certain amount of time passes, the original art and any rights granted will revert to the artist.

The artist will also want copies of the art in its reproduced form. So the contract should provide that a certain number of copies of the art as reproduced will be provided free of charge to the artist. These samples are helpful for updating portfolios and related promotion.

In addition, the textile designers’ contract requires that the client provide insurance covering the fair market value of the art when it is being shipped.

Releases

If the client is supplying reference materials, the client should guarantee that use of these materials will neither violate anyone’s right of privacy nor infringe any copyright. If this guarantee (called a warranty) is breached, the client should agree to pay any judgment as well as legal fees and court costs resulting from a lawsuit. Artists may also be asked to give warranties and indemnities for images they create, as is discussed with respect to book publication contracts on pages 169–177.

Payment

The contract must state a time for payment, usually within thirty days of the submission of an invoice (although some clients take sixty or even ninety days to pay). Some artists include a contractual term charging interest for late payment. While rarely enforced by the artist due to the desire to keep the client’s good will, such provisions may encourage timely payment. Some magazines pay on publication, rather than on acceptance of a contribution. This is not a desirable practice, since the artist is simply loaning money to the publisher. It also raises the risk that there will be no payment, since the magazine is under no obligation to publish the contribution. Payment on acceptance is best, but certainly payment should be required if publication does not occur with in a reasonable time (such as six months after acceptance).

Estimates

If an estimate is given for an assignment, it should be specified whether or not the estimate is binding. For example, the designer’s contract states than any estimate is a minimum only. However, the billing may not be increased more than 10 percent above the estimate without the client’s approval. Any estimate must leave flexibility unless the scope of the work can be very precisely delineated.

Modifications

It would be ideal to have any modifications be written, but to keep work progressing smoothly oral modifications may be unavoidable. Such changes should be promptly confirmed in writing, especially if the fees or expenses will be increased due to the change.

The contracts require that the client object to terms either immediately on receipt or within ten days of receipt. If the client complies with this, it will help to achieve a meeting of the minds.

Invoices

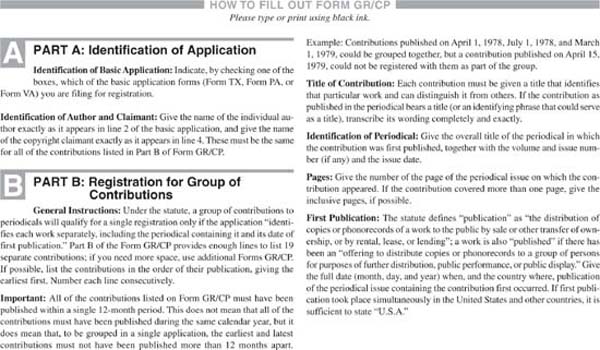

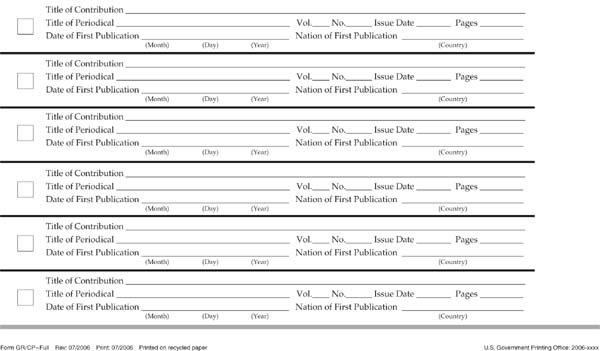

The form for photographers is designed to serve as an estimate, confirmation, or invoice. On the other hand, the forms for illustrators, graphic designers, and surface/textile designers are for use only as estimates or confirmations. The Guild has created separate invoice forms for each of these disciplines. Since the invoice forms are very similar to the estimate and confirmation forms, only the Guild’s invoice for illustrators has been included with the forms at the end of the chapter as a sample of how an invoice differs from an estimate and confirmation form.

An estimate is used in seeking an assignment, a confirmation after an assignment has been received, and an invoice after the assignment has been completed. The invoice specifies the fee and includes most of the terms that appeared on the confirmation form, including the payment terms. It usually accompanies delivery of the finished assignment or is sent on acceptance of the assignment. If extra charges have been incurred that did not appear in the confirmation form, the invoice can include such charges. The invoice would also bill for the sales tax, if any were payable.

Syndication Agreements

A syndicate gathers marketable features for distribution on a regular basis to markets, such as newspapers. Cartoon strips are commonly syndicated. The basic considerations are similar to those of the book contract discussed in the next chapter, but the creation of unique characters can have some special implications. For example, the creators of Superman sold all their rights and benefited hardly at all from the phenomenal success of Superman as a comic strip and as a character in numerous other commercial ventures.

The Cartoonists Guild in their Syndicate Survival Kit (now out of print) states that the artist selling greater rights (such as “all rights” instead of only “first North American rights”) should receive a greater payment. But the Guild strongly urges that the term be limited to no more than one or, at most, two years. This is to enable the artist either to negotiate a better contract, if the comic strip is a success, or to stop working on an unprofitable venture, if the comic strip is not popular. Since automatic renewal would defeat the purpose of a short term, the artist should refuse any such renewal provision.

The artist is normally paid in the form of a percentage of the receipts earned by the strip. But again, the artist should be careful that the percentage is taken against gross receipts, not net receipts (which might also be phrased as “gross receipts less expenses”). The Guild suggests 50 percent of gross receipts is usually fair payment to the artist, but indicates a minimum payment should always be specified. The Guild urges the artist to reserve a fair percentage of gross receipts—75 percent, perhaps—from all subsidiary rights, particularly since book, television, radio, periodical, and novelty rights can be so valuable when cartoon characters are successful.

The Guild suggests that the artist retain copyright in the work, in which case copyright notice should appear in the artist’s name. The artist should require powers of consultation and approval with regard to any changes to be made in submitted material. Also, the original artwork should be returned to the artist.

The Guild stresses the importance of promotion for the success of a cartoon strip. The promotional plan should, ideally, be agreed upon in advance. The burden of promotional costs and the rights to use the work for promotion without additional payments should be resolved at this stage too.

The artist should have a right to periodic accountings showing the source of all receipts and the exact nature of any expenses. The artist should be able to inspect the books of the syndicate. Package deals, in which several features are sold together, should be forbidden. Each feature should stand on its own merit and be paid for individually. The Guild also suggests that legal fees and liabilities should be equally divided between the artist and the syndicate.

The artist must not relinquish the right to sell other creative work. The syndicate has received a license with regard to the comic strip at issue, so work that is too similar will infringe that license. But the artist should not agree even to refrain from marketing similar work because of the problem of defining what may be similar. Any option provision giving rights over future work of the artist to the syndicate should also be struck from the contract.

The Guild suggests that, in the event of the artist’s death, controls be present in the contract that ensure payments for the comic strip will continue to be made to the artist’s estate. One possible way to do this would be to require minimum payments to the estate after the artist’s death. Another way might be to have the estate pay for a replacement artist, who would continue the comic strip.

Commercial exploitation through the reproduction of artwork can take the form of jewelry, t-shirts, posters, prints, and even useful household objects (such as lamps with decorative bases). The artist who is offered an opportunity to exploit copyrighted or patented work can limit the rights licensed with regard to use, duration, and geographical scope. The artist will want to be certain that the entrepreneur seeking the license is financially stable, respected for honesty, and capable of creating and distributing quality products.

The entrepreneur would normally bear the cost of reproducing the work, possibly under a binding schedule for production. The artist would want the right to approve the quality of the product at the various stages of manufacture. Promotional budgets and approaches might be specified in advance along with channels of distribution. Appropriate copyright, trademark, and patent notice; the right to artistic credit; the artist’s ownership of the original work; the artist’s right to free copies; and any warranties given by the artist would all be included in the contract.

The artist might be paid either a flat fee or a royalty. If a royalty is to be paid, the issue of gross and net receipts again becomes significant. The artist will want a stated percentage of the gross receipts, not the net receipts (or gross receipts less certain expenses). Nonetheless, the typical deal is to give the artist 5 to 12 ½ percent of the net wholesale price received by the manufacturer from its distributors. The artist would want the right to both periodic accountings and inspection of the entrepreneur’s books.

The entrepreneur might request that the artist either refrain from creating competing works or offer an option on the artist’s next commercial creation to the entrepreneur. The artist should not agree to these provisions, however, for the same reasons discussed in the next chapter with regard to book contracts.

The contract should provide for termination in the event the entrepreneur fails to exploit the work or becomes bankrupt or insolvent. The rights would then revert to the artist who might be entitled to purchase stock on hand at the cost of the stock to the entrepreneur.

The commercial exploitation of art is merely a more general application of the principles that guide the artist in the specific exploitation of art involved in a publication contract. For the artist considering such a commercial venture, the principles discussed for the book contracts will be a helpful guide. An excellent guide to this area is Licensing Art and Design by Caryn Leland (Allworth Press).

Model Contracts

The photographer’s assignment agreement form is reproduced here by permission from Business and Legal Forms for Photographers by Tad Crawford (Allworth Press). The graphic designer’s estimate and confirmation form, the surface/textile designer’s estimate and confirmation form, the illustrator’s estimate confirmation form, and the illustrator’s invoice were all drafted by me for the Graphic Artists Guild. They are reproduced here by permission of the Guild. The Web site design contract is reproduced here by permission from Business and Legal Forms for Graphic Designers by Tad Crawford and Eva Doman Bruck (Allworth Press).