2

Organizing the past

Given the diverse intellectual and institutional origins of modern academic architectural history, it is hardly surprising that contemporary architectural historians would approach the task of analysing the past from any of a number of different perspectives. This chapter surveys some common strategies for considering architecture historically. Each evidences a form of (usually benign) historicism, a conception of the past’s relation to the present, and thus of the present’s historicity. Herder invoked this consciousness when he wrote, ‘A slender thread connects the human race, which is at every moment breaking, to be tied anew.’1 The division of architectural history by a chronology governed by style and period is one of the earliest, more traditional and most persistent approaches to this problem. The problems of defining specific styles and understanding the transitions that occur between one style and another (gothic to Renaissance; Renaissance to baroque) constitute the first disciplinary problems of architectural history. For these reasons we will consider it first, and in slightly greater length than other approaches.

During the nineteenth century, the confluence of stylistic, cultural, social and historical factors in the composition of contemporary buildings prompted architects and historians alike to align architectural styles, including proportional and ornamental systems, with their historical origins, which in turn bore a set of values. When a building could be designed in the manner of a historical style – classical, byzantine, baroque and so forth – the historian’s question of how to define a style assumed a greater importance for the theory and practice of architects. ‘In welchem Style sollen wir bauen?’ asked Heinrich Hübsch in 1828: ‘In what style should we build?’ Hübsch’s essay provoked a debate on the theme among German architects and academics of his time, during an era in which, to quote one of his respondents, architects could be found working ‘in every style or none’.2

A more pragmatic discussion on this same set of issues could be found centred on Cambridge around this time – echoing countless others elsewhere. Members of the Cambridge Camden Society (established 1839) held strong views on the appropriate style for Anglican churches in Britain’s new colonies and territories. Writing in their journal Ecclesiologist, George Selwyn, Bishop of New Zealand, in 1841 advised that ‘Norman is the style adopted; because as the work will chiefly be done by native artists, it seems natural to teach them first that style which first appeared in our own country.’3 For the nineteenth century, when stylistic decisions no longer seemed given, much thought was dedicated to determining the most appropriate appearance for a building in any specific setting. Where German architects appreciated the problem faced by their nineteenth-century contemporaries as concerning the choice of style among a relatively free range of options, the Cambridge Camden Society saw a more natural logic to the selection of a style appropriate to a place relative to the pace of its religious, artistic and technical progress.

The histories of architectural style that appeared in the nineteenth century thus contended with two kinds of problems. How, on one hand, could the past be known and represented? And how, on the other, could those architectural styles embodying recognizable values be taken up or set aside within a long process of cultural assessment and assimilation? As we shall shortly see, stylistic histories of architecture contributed to the nineteenth century’s larger cultural projects of knowing the world in its entirety (witness the world exhibitions, encyclopedias) and constructing taxonomies of all things, from insects, fish and the chemical elements to culture and its multiform expressions.4 Likewise, questions of style and stylistic transformation were fundamental to the disciplinary toolkit and cultural ambitions of architectural historians working at the end of the nineteenth century and thus steered, at least initially, the nascent academic field of architectural history.

Approach

The following pages consider a number of ways in which architectural historians have, from the later decades of the nineteenth century, addressed the task of writing about the past. We might think of this as an issue of method. Where methodological differences between one historian and another can seem marked in early cases, however, they tend to be more ameliorated in recent histories of architecture, to the extent that it is often unproductive to apply a methodological schema to the field of architectural history, or to understand the work of an architectural historian purely on methodological grounds. We might speak instead of methodological biases or allegiances, but these will rarely be doctrinaire.

The softer term ‘approach’ is therefore useful for attending to the various ways in which historians of architecture address the question of architectural history’s ‘unit’, while acknowledging that an individual will often use combinations of frame, material and method that best suit the subject of a historical study. The term ‘unit’ here refers to the way the historian divides into workable portions the ‘total history’ of architecture – the hypothetical but obviously impossible complete past of everything that has happened everywhere at all times as it can be understood from all perspectives. The question of the historian’s approach can also help us to appreciate how he or she deals with the management of architectural history’s apparent demand for infinite relativism, whereby all knowledge depends on the point of view from which it is generated and represented.

Aside from numerous anthologies that set out to group essays and extracts from books into methodological or theoretical categories, a number of monographic studies, mainly concerning art history rather than architectural history, will shed further light on the points raised throughout this chapter.5

Mark Roskill’s What is Art History? (1976) works through a series of conceptual and methodological themes, sticking close to the history of painting, but making a number of points of interest to a discussion on methods of architectural historiography.6 The Research Guide to the History of Western Art, by W. Eugene Kleinbauer and Thomas P. Slavens (1982), makes many pertinent observations on style, period and transition, as well as on interpretative frameworks.7 Again their subject is the history of art, but the methodological issues and examples they raise often parallel or overlap with those found in architectural history. Laurie Schneider Adams’s well-organized survey The Methodologies of Art includes discussion and examples of a range of media and positions on art-historical method.8 Likewise, Michael Podro’s The Critical Historians of Art (1982) is an astute biographically arranged study of perspectives and approaches. His book also principally concerns art historians, but many of these, as we have considered above, wrote on architecture and also fall in the remit of our interests.9 In his book Methodisches zur kunsthistorischen Praxis (1977), Otto Pächt works across artistic media, including architecture, to offer a personal but privileged insight into methodological problems shared by historians of art and architecture.10

In this chapter we consider six approaches to the organization of the past of architectural history: style and period, biography, geography and culture, type, technique, and theme and analogy. An architectural historian would not tend to follow one of these modes exclusively. As such, these headings are much less a methodological map of the field of architectural history than a limited survey of historiographical approaches, where one is often tempered through its combination with others.

Style and period

In an essay called ‘Style’, first published in 1962, James Ackerman observed that ‘for history to be written at all we must find in what we study factors that are at once consistent enough to be distinguishable and changeable enough to have a “story” ’.11 For the historian of art and architecture, ‘works … are the primary data; in them we must find certain characteristics that are more or less stable’. Style, he writes, is a ‘distinguishable ensemble of such characteristics’.12 Works of art, and works of architecture among them, are rarely preserved for their intrinsic artistic merit. This means that the facts and circumstances of a building’s conception and realization are susceptible to loss over time. The intentions, formation and even the identity of the artist, architect or mason can be obscured, or disappear entirely. In these circumstances especially, ‘style is an indispensable historical tool; it is more essential to the history of art than to any other historical discipline’.13 Nevertheless, style is a structure applied by historians to history rather than a logic extracted from the past. The question the historian must ask, Ackerman notes, is ‘what definition of style provides the most useful structure for the history of art?’14

When Heinrich Wölfflin, writing half a century earlier, posed the possibility of conceiving of an ‘art history without names’, he too proposed that one could understand architecture’s history on the basis of its appearance and visual character and the changes to which they were subject over time. Ackerman’s reflections on style soften the sometimes-hard formalism of Wölfflin’s approach, rendering style useful as an analytical category without requiring adherence to a doctrine. For both historians of architecture the evidence for a stylistic history would be the building itself. The stylistic makeup would include decoration, details and the visual organization of the building’s façade given by the architectural order used in its columnation, or its form and massing. How does a building balance stability and change within history? Why do styles change over time? How can we know one style from another? How can we name stylistic periods, and understand how they rise and fall, when architecture as a category of the arts is made up of individual works?

Wölfflin belonged to the first generation of those who sought to systematise historical knowledge of architecture among the arts. In Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe he lent analytical criteria to stylistic divisions based on a comparative method of visual analysis, observing that styles followed a cyclical path from nascent, to classic, to baroque states. The nascent state held the promise of the classic, just as the baroque traced its deterioration. The question embedded in the introduction of Renaissance und Barock follows this logic: how did we go from Raphael and Michelangelo to Maderno and Borromini in a few short decades? For Wölfflin, ‘baroque’ is a stylistic epithet coloured by its derogatory heritage, denoting that which is overwrought and super-exuberant, just as ‘Renaissance’ takes on the celebratory tone given it by Burckhardt – the rebirth of an ancient model, sure of its principles and close to a beautiful ideal.

Wölfflin’s Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe goes much further than this judgement by codifying the methods for the kind of formalist analysis on which his own histories rest.15 He lays out a set of now well-known dichotomies to explain the differences between classical and baroque buildings, paintings and sculpture: linear versus painterly, plane versus recession, closed versus open form, multiplicity versus unity, and clearness versus unclearness. Wölfflin’s own lectures at the universities of Basel, Berlin and Zurich followed this comparative technique. He would show two slides at once in order to describe and explain the differences between one building and another, and hence between one stylistic category and another. Until the advent of digital projection, the paired display of slides was a common tool for teaching the history of art and architecture. It was initially bound to the formalist, rather than iconological, teaching of architectural history, but was later widely adopted by many teachers who paid little heed to its original methodological connotations.

For Wölfflin, style concerns deep structure as well as appearance. It is the device by which we can tell one architect or writer apart from others, but also families and generations of buildings. Just as in speech, writing and dress, we can with variable levels of confidence tell the difference between products of the seventeenth century and those of the nineteenth, between those of the twelfth and of the fifteenth. It is this concept of style of which Peter Gay wrote in 1974 (of styles of history-writing):

Style is the pattern in the carpet – the unambiguous indication, to the informed collector, of place and time of origin. It is also the marking on the wings of the butterfly – the unmistakable signature, to the alert lepidopterist, of its species. And it is the involuntary gesture of the witness in the dock – the infallible sign, to the observant lawyer, of concealed evidence. To unriddle the style, therefore, is to unriddle the man.16

Between Ackerman and Wölfflin, then, we have two different approaches to understanding style historically, each with connotations for the writing of history. Wölfflin maintains the idea that style is a visual revelation of the state of a work, which is a product (and therefore an index) of its time. The historian can understand a culture by understanding its art. The periodic division of historical time follows this logic, whereby the Renaissance, for example, is first a social, political and economic development, and secondarily a development in the arts. As we might expect to find with the passage of decades, Ackerman’s position ameliorates Wölfflin’s and comes closer to a flexible working definition of style.

The word style defines a certain currency – distinguishable in the work (or in some portion of the work) of an artist, a place, or a time – and it is inefficient to use it also to define the unique traits of single works of art; uniqueness and currency are incompatible. The virtue of the concept of style is that by defining relationships it makes various kinds of order out of what otherwise would be a vast continuum of self-sufficient objects.17

Many art and architectural historians of the last century found style a useful ‘protection against chaos’.18 In his guide, L’Art de reconnaître les styles, written around 1900, Émile Bayard considers style across architecture, decoration, monuments and (principally for him) furniture.19 Style, he suggests, is fundamentally physiognomic, and, for architecture and furnishings as for animals and vegetables, one can trace developments of new species and within species, each responding to the constraints of ‘nature’ and the inclination to ‘progress’. We can appreciate, of course, how the analogy of ‘recognizing’ styles as one recognizes the features of an individual in relation to categories is a product of nineteenth-century thinking in the natural sciences. It relies on a capacity for a rigorous taxonomy that most historians of architecture can no longer countenance, but which was an important aspect of stylistic architectural historiography in the first part of the twentieth century. This followed the nineteenth-century examples, especially, of Fergusson and Fletcher, and was manifest, for instance, in the global survey (from antiquity to the middle ages) of François Benoit.20

It is not enough to understand that with stylistic labels come fixed rules pertaining to proportion, decoration, colour or any other factor governing a building’s appearance. Whereas many have soundly rejected the notion of a stylistic system for the history of architecture, it has often been replaced awkwardly by chronological groupings that serve as stylistic epithets in disguise. Other debates have circled around the propriety of using stylistic and periodic terms that were later applied to historical phenomena as unifying devices (Romanesque, gothic, rococo) alongside stylistic labels under which architects grouped themselves contemporaneously (International Style, postmodernism, deconstructivism). Where one lends order to chaos, to again recall Ackerman’s phrase, the other manipulates the techniques of historians to historicize architecture as it is being made, and in these examples facilitate its entrance to the museum. This latter approach sets out tenets against which individual examples can be tested, and within which subsidiary groupings will appear. Dutch International Style can be distinguished from North American by the expert, as can that of California from that of New England. Progressive historians and theoreticians of architecture might treat postmodern historicism as conservative while ascribing to formal postmodernism and the neo-avant-garde the progressive tones of modernism.21

These examples are deliberately blunt and can be easily contradicted so as to expose the inevitable fallacies faced by schemes that set out to organize the history of architecture according to appearance. Any stylistic or periodic organization of past buildings and monuments will introduce the problems of reconciling the individual example with a normative rule against which very few cases can be measured without compromising either the single building or the norm against which it is measured. Where a label offers a useful visual trigger for the historian, it would these days be treated with a healthy dollop of scepticism, and, when deployed, viewed as a ‘soft’ rule, recognizing exceptions as being more than failed attempts to fulfil a perfect model. The relatively recent appearance of the stylistic term ‘Renaissance Gothic’ is a good example of historians recognizing the inadequacy of monolithic stylistic–periodic terms to describe historical examples.22

On this point we ought to turn briefly to one application of stylistic divisions in architectural historiography, namely, the process of arguing the representative character of a building in legal cases concerning architectural heritage, especially of the last two centuries. To what extent is the building at hand exemplary of Federation Style or of Georgian or of Neo-classical or of Modernism? Note the capital letters, denoting hard definitions of these styles. For the architectural historian giving evidence, this kind of assessment would seem outdated, but it has strong traction outside of the academic study of architectural history and remains a useful tool in the classification and protection of architectural heritage on formalist or aesthetic grounds.23

6 Renaissance Gothic: Stephan Weyrer the Elder, Church of St George, Nördlingen, nave and choir vaults, c.1500.

The formalist and taxonomic approaches to style that marked the work of architectural historians in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries have had a more productive afterlife than the staid identification of styles and periods, in many cases opening the work of architecture and its history to questions of philosophy and the deeper structures of culture. They have also allowed historians of architecture to pursue the relation of architecture to the visual arts (principally painting and sculpture) on chronological grounds other than biography, which we shall consider next. This connects artistic production to time and raises the loaded question of the degree to which time lends the architect the constraints of their practice. Do technology, religion, social mores, taste, economics and other external factors shape architecture’s appearance and inform its capacity to change, or does architecture govern its own formal laws according to its own body of theory? This question remains open to debate.

Those architectural historians who accepted Arnold Hauser’s invitation (1959) to write a ‘Kunstgeschichte ohne Namen’ based on the measure of society rather than style accepted that architecture’s appearance could be informed by factors completely external to the artistic workings of architecture and its traditions.24 The classicism of the Renaissance manifests the new economic, religious and political conditions of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries on the Italian peninsula. To take Renaissance architecture as a unit of analysis is not, therefore, to accept the stylistic unity of this architecture as a purely architectural phenomenon. From this point of view, it is rather to regard this architecture as evidence of historical forces unified by factors that remain relatively constant across the period marked by the emergence of a market economy from a feudal society, until to the Sack of Rome and the religious wars heralded another fundamental shift in the bases of society and culture.

The architectural histories of this period by Charles Burroughs, Manfredo Tafuri and Deborah Howard all engage the problem of architecture’s subjection to extra-artistic forces, but they do so within the traditions of cultural history, treating the Renaissance as a cohesive historical epoch containing the full range of its expressions.25 This division of architectural history according to major historical events and the various degrees of historical cohesion they allow historians to address is a legacy of the cultural histories of Michelet and Burckhardt. It accepts that architecture is a manifestation of culture, and therefore a form of historical evidence – traces of historical forces that are evidenced, too, by a range of cultural and social phenomena.

The bifurcation of historiographical positions during the 1950s and 1960s on the meaning of mannerism in sixteenth-century Italian art and architecture highlights a key difference between internal and external criteria for the cohesion of historical periods.26 Mannerism is itself a contentious term. Among those historians for whom it had some valency, however, some understood mannerism as an artistic, linguistic deformation within the classical tradition, while others positioned it as an expression of the uncertainties of the age, of the loss of surety and the universal values of the Roman church. One historiographical value (invention) is architectural and artistic; another (anxiety) is cultural, societal and religious. Particularly in more recent decades, architectural historians have shifted from the treatment of ‘internal’ historiographical categories of past epochs: the Roman Empire, the middle ages, the Renaissance, the Counter-Reformation, the modern world since the Industrial Revolution. The architectural history of politico-cultural periods, indicated in such epithets as Weimar Germany, New Deal America, Fascist Italy, Colonial Brazil, Soviet Russia, post-war Japan and so forth, take architecture as a trace of events and agendas that are not its own, but which nevertheless implicate its historical development.

The division of history by style and period is not, therefore, a monolithic approach, even if it has enjoyed a sustained role in organizing the history of architecture. Style and period open a door on the question of the extent to which architecture’s internal artistic forces balance those that shape it from the outside. Conceptually, style and period have some fundamental differences, but as categories that allow the architectural historian to begin arranging the drawings, buildings and ruins of the past they share an abstract approach to historical time based on variable unities within definable parameters. This returns us to Gay’s definition of style and the problem it has posed for historians of architecture. If style is, indeed, the pattern in the carpet, the markings on the wings of the butterfly, and the gesture of the witness in a court case, then the problem this leaves the historian of architecture is how to account for the origins of these patterns, marks and gestures. When they occur within the history of architecture, are they architectural in nature, or historical?

Biography

As we saw in the first chapter of this book, the tradition of writing biographical portraits of artists, including some figures we now identify as architects, offered one important model for an academic architectural history as it emerged at the end of the nineteenth century. This tradition indexed examples like Antonio di Tuccio Manetti’s biography (c.1480) of Brunelleschi and Vasari’s sixteenth-century Vite.27 It equated architectural history with the history of architects. However far contemporary architectural histories concerned with the architect might have moved from Vasari’s mode of writing history, they still owe to him the fundamental division of time according to lifespan, its trajectory and works, and its repercussions and relations with other biographical entities. The life-and-works genre of architectural history is a persistent way of accounting for the contributions of the individual to history.

We could spend a great deal of time on its mechanisms alone. The observations that follow, however, also pertain to a biographical organization of architectural history concerned with corporate entities and the activities of patrons, like emperors, popes and presidents. Architectural histories that plot the origins, intentions, influences and impact of a government or institution can likewise assume some of the characteristics of a biographical architectural history. Indeed, a building, or a city, can be said to have its own life, and the terms and structures of biography can inflect its histories: foundations, rise to prominence, height of influence or importance, and dénouement – literary strategies, indeed, dramatic even, but shared with biography nevertheless. The kind of architectural history with which this section is concerned is, therefore, an architectural history organized in relation to an entity that either is biological or sustains a biological analogy. Because the history of architecture has enjoyed a long and close association with the figure of the architect, we will focus our attention on the organization of historical time according to the life of the individual architect: the biographical architectural monograph as a genre of architectural history.

This kind of history treats architecture as evidence of the architect’s actions and intentions. From this perspective, one architect’s lifework connects to another’s by means of his or her formation, motives, influences (exerted by or on the subject), settings, opportunities and, more loosely, professional and artistic genealogies. This approach has in recent decades also allowed for the psycho-biographical interpretation of historical subjects. However a life is constituted historically, and however the historian might deal with the content of that life, a subject’s birth and death lend firm starting and finishing points to any given subject. (Against this observation one might substitute a partnership’s establishment and dissolution; or a government’s rise and demise.) These often determine the most immediate associations of a lifework to a period, style, type, geography and so on. They can also inform the way that one individual subject relates to another, or that subjects relate to the numerous contexts that shape or colour historical events. The facts and conditions of an architect’s birth and death lend architectural history an order determined by biographical progression – of the stages of life, and of the relationship of the architect as an individual and the external forces acting upon him or her.28

It is important to recognize that biography is inevitably, to a greater or lesser extent, a construction of its author. The historical treatment of biographical subjects will be informed by the historiographical trends of the time in which the work is written as it seeks to present what is known and can be known (and is relevant to know) of the individual concerned. Many major figures of the architectural canon furthermore index broader historical developments in architecture: Brunelleschi for the Renaissance, Borromini for the baroque, Thomas Jefferson for the Enlightenment, Le Corbusier for modernism, and so forth. To invoke one or other of these names is to recall the entire baggage of this association and the historical discourse that has already accrued around it.

Architectural history organized along biographical (and occasionally autobiographical) lines most commonly includes monographs, as well as the œuvre complète, which present a known body of an architect’s work and establish frameworks for its analysis. This is a favourite curatorial mode of the museum, because the facts of a person’s life can often be made to lend neat divisions for the interpretation of the subject’s work. These might include major life events, travel and migration, realization (or not) of significant works, and so forth. Even if those divisions can be called to account by an exhibition’s critics, a knowing reviewer or other literature in the field, they regularly establish a basic chronology and organizing structure.

A biographical organization of architecture’s history relies on a concept of architecture as an authored work, and of the architect as an artist or craftsman – an active agent in the work. This idea is relatively recent, enjoying continuity only since the Renaissance. Even when architectural history makes a claim on the city, it is feasible to name ‘authors’ against whom one can measure the unfolding of an intentioned plan, such as Albert Speer for the Third Reich’s Berlin, Robert Moses for modern New York, Ernst May for Das Neue Frankfurt, and – citing more obvious examples that evidence a heavier individual hand – Walter Burley and Marilyn Mahoney Griffin for Canberra, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret for Chandigarh, and Lucio Costa for Brasilia. In these instances, the plan can be understood to have the autonomy of an architectural work in order that it can be considered in light of the architect’s œuvre.

Two major exhibitions on Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) were staged concurrently in New York in 2001: Mies in Berlin at the Museum of Modern Art, and Mies in America at the Whitney Museum of American Art.29 Together they illustrate some of the points raised above. Here the architect’s work is organized along the clear division of his European and American ‘periods’, divisible by his 1937 emigration from Germany. How does Mies’s work change after his move to Chicago? What aspects of his work ‘belong’ to Berlin? And what property belongs to the US? What among his work and ideas transcend the place of his practice – or the intellectual and artistic context of the modern movement, for which he is customarily claimed? The trajectory of this story can be cast long – from earliest influences on the young Mies to his posthumous influence on others – or short – from the first building to the last. The bio-geographical division maintained by the two museums and curatorial teams (led by Terence Riley and Barry Bergdoll at the Museum of Modern Art and Phyllis Lambert at the Whitney) suggests a large subsidiary unit of ‘the life’ within which Mies historians find smaller sets of his architectural projects.

7 Mies and America? Jacqueline Kennedy chatting with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 12 April 1964, Hyannis Port, Mass.

Biographical architectural history raises a number of specific conceptual issues. The reasons for any biographical turn can be given as hard or soft, evidencing direct causality or the subtle influence of any number of circumstantial factors working together. An architect’s lifework might give rise to persistent themes, which take on the appearance of an intellectual or artistic project that demands interpretation as much as it defies it, or that justifies aligning the architect with others who appear to share his or her professional and artistic concerns. The degree to which a specific building, suburban plan, monument or unrealized design can be wholly explained by the architect’s enduring artistic, cultural or technological project; by the architect’s personality; by the cultural, historical and geographical circumstances of his or her life; or even by the explanations he or she might give for the work at hand: each is open to criticism by those who would put the external forces of economics, politics, religion, materials, building technology, intellectual formation and professional institutions into play as forces stronger than any one architect’s will.

Many architectural histories written in the biographical mode are openly hagiographic and set out to install an architect in the canon or to defend his or her place there. Many architects themselves have not proven averse to writing historical accounts of their own lives and practices, with the effects ranging from critical to advertorial. Even the most obviously biased and blinkered studies of individual architects can, however, serve the valuable function of documenting the relevant facts and sources relating to someone’s life in practice. Those books and exhibitions produced with the aim of introducing an architect to the world are often works of passion and dedication that are a fundamental foundation of materials upon which a later historian can build as he or she works back over the subject. Subsequent research will inevitably uncover new materials, revise chronologies and reassess the significance of individual projects. That does not diminish the importance of the first step of recording the architect’s life and work. Indeed, much of what we call ‘critical architectural history’ relies on this initial, often uneven layer of research and analysis.

Other architectural histories openly seek to strike a balance between intrinsic and external forces acting on the architect’s work, even if this results in a more ‘realistic’ (or compromised) portrait. The volumes organized and introduced by Marco De Michelis on Heinrich Tessenow, 1876–1950 (1993) and Johan Lagae on Claude Laurens (2001) tread this line to great effect.30 Each follows the rules of an œuvre complète, reflecting on the various meanings that one might impose on the biographical subject, between free agent and index. Like the books on Mies van der Rohe introduced earlier, they nevertheless treat their respective architects critically as well as historically, testing their work against themes and comparative cases that hold their subject accountable to the broader histories in which they take part, all the while retaining the clear limits imposed by life’s boundaries and trajectories.

Geography and culture

The characteristics of an architectural history shaped by biographical factors parallel those borrowing limits from national, imperial, regional, municipal and other geo-political borders, or those that map onto cultural and/or linguistic territories, extra-territorial groupings and geographies, or diasporas. The architectural history of a nation can be studied as a discrete field of knowledge, despite the obvious complications and compromises that inevitably arise from modern nations sharing borders that have been subject to varying degrees of permeability, or that are introduced by immigration and emigration. The architectural history of a contemporary nation, for example, might include formerly discrete territories, or discernible linguistic regions whose architectural history has developed coherently within a larger nationalist grouping. A twentieth-century nation might be subject to the mechanisms of colonization, connecting one territory and its history with that of the colonial party, and ultimately to its other colonies. The architectural histories of South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and Canada are distinct on any number of terms while sharing the colonial experience under British rule.31 So too for South Africa, Indonesia and New York in relation to Dutch colonization. Few historians of architecture would regard the concept of nation or territory to be so straightforward and passive as the lines of a map suggest. This is not to say that these lines do not offer a useful starting point for considering the architecture of a territory or culture.32

A history of Swiss architecture, to give one example, might be resolutely introspect or openly treat the problems, both practical and conceptual, of architects moving easily between one country and another, originating in Switzerland or moving there, or identifying strongly with one neighbour or linguistic community. A curious example of a history contending with this kind of geographical permeability is the American G. E. Kidder Smith’s modernist history and photographic survey Switzerland Builds: Its Native and Modern Architecture (1950). In a long preface, the Prague-born Swiss historian Sigfried Giedion offers a distracted reflection on the ‘character’ of the Swiss, which is extended in the content of Smith’s account. Giedion’s ‘Introduction to Native Architecture’ begins with this explanation:

The native, or vernacular, building shown on the following pages is comprised of the dwellings in which the people of the country live, and the buildings which they use in gaining their livelihood, such as barns and agricultural adjuncts. The book will not deal, except in passing, with the richer communal monuments or public buildings of derivative ‘styles’ – largely foreign – for these, even in remote districts, were almost always done under the patronage or influence of the church or local government, both of which were well versed in architectural developments abroad. Churches will be touched upon because they are so intimately tied up with the lives of the inhabitants, but not the cathedrals, nor the Renaissance, Gothic or Baroque as such. These forms can be seen in far finer examples in the countries of their origin on the four sides of Switzerland.33

The qualification for being included in Switzerland Builds is the demonstration of a native character. For Giedion this excludes those works of Swiss architecture that adopt and adapt styles, forms and types that originate elsewhere and thus speak to (for instance) the history of ecclesiastical architecture in Europe.

Published almost twenty years later, New Directions in Swiss Architecture (1969) is a book of comparable scope and intention. Its authors Jul Bachmann and Stanislaus von Moos take a more ambivalent stance to Smith’s qualification of autochthonous character. Although the country can lay claim to some clear identifications, namely ‘machines, chocolate, cheese, and watches, and beyond its famous “neutrality” ’, they ask ‘is there any value which could be defined as specifically Swiss?’34 The scope of Bachmann and von Moos’s book is close to that of Smith’s. Both concern modern architecture, but whereas the latter example seeks out that work demonstrating a real affinity with the place, the former considers the function of the territory as a setting for exchanges that work between Swissness and European internationalism.

At the risk of spending too long on this one national example, a third book, roughly contemporaneous with the previous two, illustrates one further stance available to historians concerned with the limits offered by geo-political borders. Eberhard Hempel introduces his authoritative contribution to Pevsner’s ‘Pelican History of Art’ series, Baroque Art and Architecture in Central Europe (1965), with a series of historical and conceptual observations.35 These concern economics, arts and letters, religion, the organization of arts practices, and patronage and style, before undertaking studies bordered on one side by territory and on the other by chronology. Hempel divides his book chronologically, with his history concerning (to cite his subtitles) Painting and Sculpture: Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries and Architecture: Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries.

Curiously, Hempel treats political territories as mobile categories in relation to the broader subjects of the book (architecture, painting and sculpture). Therefore, in the sections entitled ‘The Heroic Age, 1600–39’ and ‘The Years of Recovery after the Thirty Years War, 1640–82’, territorial cases fall under the heading ‘Architecture’ – Austria, Hungary, Bohemia and Moravia, etc., and Switzerland also. The two subsequent sections, entitled ‘The Baroque Period, 1683–1739’ and ‘Rococo and its End, 1740–80’, take their headings from these territories, which are then further divided up to three times: into ‘Architecture’, ‘Sculpture’ and ‘Painting’. Some miss a category. Prussia is considered for its contribution to the baroque period, while Silesia’s rococo arts rate merely a passing mention.

Switzerland participates in broader artistic and historical phenomena shared by Austria, Hungary and Poland, for instance, but lends to these broad developments grouped under the broader geography of Central Europe a cultural, historical, geographical and technical specificity that must (for Hempel) be balanced out with the general history of this period.

The depth of histories framed on geo-political grounds is also determined by the histories of the borders themselves. Hempel’s history of Central European baroque reconciles contemporary (for 1965) nations with former territories. The former state of Czechoslovakia, therefore, appears among his subheadings, but so do Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia, which formed part of that state from 1918 to 1993, and part of the Czech Republic to the present. Looking farther south, an architectural history of Austria, for instance, might expand and contract its geographical remit along lines determined by the influence of Vienna, from duchy to Empire to Republic. Such a history of Austrian architecture would, therefore, intersect with the architectural histories of Poland and Turkey, which are themselves subject to the same problem of territorial fluidity over time. For Austria, but also Poland, Germany, the Czech Republic and other contemporary states, the added complexities introduced by migration in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as well as by the mid-twentieth-century diaspora of Jewish architects, would allow some historiographical frameworks to claim buildings in the United States, South Africa and Australia as ‘Austrian’ (to keep to this example), or more specifically as ‘Viennese’, or at least bound to an Austrian or Viennese architectural patrimony.

What do the methodological divisions in architectural history of biography and geo-politics have in common? For one thing, they share the need to negotiate the balance of the general with the particular: how far can we read an individual architect’s work as an index of his or her generation? Or the architecture of a distinct state, kingdom or region as manifestations of broader transnational or international currents? Historians of the modern movement have, in particular, faced this problem, from both biographical and geo-political perspectives. How far can architectural historians press the specificity of their subject, the irreducibility of the biographical, or of the national?

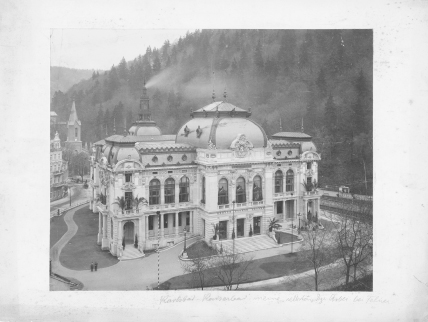

8 Whose heritage? Kaiserbad Spa (now Bath I) at Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic, architects Fellner und Helmer, Vienna 1895, atelierchef Alexander Neumann, photographer unknown.

In most cases, geo-political limits offer a useful and easy way to restrict an architectural history. These limits, though, are neither natural nor static. There is much to learn of the historian’s own context in the way he or she constructs a territory, geography or culture.

Type

The correlation between the form, character and organization of a building and the purpose it serves led observers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to regard architecture as analogous with any number of other phenomena, natural or cultural. Like birds, paintings, rocks and people, buildings could be divided into families that could be understood independently of history. A typological approach to architectural history married the values of intellectual pragmatism with the empirical division of buildings into categories shaped by how they appeared to work. In his Dictionnaire historique d’Architecture (1832), Antoine Quatremère de Quincy explains the nature of the term as applied to architecture:

The word type presents less the image of the thing than the idea of an element which must itself serve as a rule for the model. … The model, understood in the sense of practical execution, is an object that should be repeated as it is; contrariwise, the type is an object after which each artist can conceive works that bear no resemblance to each other. All is precise and given when it comes to the model, while all is more or less vague when it comes to the type.36

As a category, then, ‘type’ is substantially looser than ‘model’, allowing for broad groupings of buildings according to shared points of reference, commonly connected to the building’s purpose. Just as architecture as such can be thought to have a history, so too can its genres. Thus we can conceive of an architectural history of the hospital, the university campus, the basilica, the factory, the museum, the high-density housing block, the railway station, the opera house, the presidential library and the airport. Each family is both figural and functional in character, and further divisible according to categories that are often suggested by the type itself: ecclesiastical architecture as a type includes sub-genres shaped by liturgy, plan-form or period; likewise, convalescent hospitals, asylums for the insane, and hospitals for communicable diseases can lay claim to their own architectural histories.

Types can be intimately tied to nature, as Marc-Antoine Laugier argued in 1753: the ‘primitive’ hut reflected an ‘ideal of perfect geometry’.37 Trees lent columns; their boughs gave shape to a rustic pediment. In a seminal article of 1977, Anthony Vidler calls this the ‘first typology’.38 Architectural types can also relate to their use, such as the examples introduced above, where the type can be followed historically as a series of changes, in the first instance, to the organization of the building plan. This is Vidler’s ‘second typology’. These generic divisions tend to be extra-architectural in nature, generated from outside of architecture and applied or evidenced in buildings. As such, these first and second typologies run in the opposite direction to style, which, although (as we have seen) it responds to external forces and provocations, is basically internal to architecture.39 Typological divisions of one kind of ecclesiastical architectural history from another are largely determined by religious, cultural and social factors rather than architectural or aesthetic qualifications. Churches that are remarkably different in appearance and that follow distinct theories of architecture can be connected typologically on these grounds and treated as a coherent basis for architectural history.40

(In addition to the categories above, Vidler also posits a ‘third typology’. This concerns the autonomous, self-referential form of architectural design that gained international currency in the 1960s and 1970s most prominently through the architectural projects and writings of Aldo Rossi. This third approach to building type reduces historical works of architecture to ‘architectural elements’ that can be transformed into the material for design and composition. This process very directly demonstrates the operative utility of architectural history for architects, a theme to which we will later return. Conceived thus, as Daniel Sherer puts it, ‘[T]he type repeats nothing exactly, but reminds us, in a vague sense … of earlier urban patterns and experiences.’41)

In his introduction to A History of Building Types (1976), Pevsner suggests that the need for a typological knowledge of architectural history is connected to the widened scope of the architect’s activities in the nineteenth century. Where architecture was once the domain of ‘churches and castles and palaces’, runs Pevsner’s argument, the architect is now concerned with ‘a multitude of building types’. Quoting the American architect Henry van Brunt (in 1886), he adds to the types named above ‘churches with parlours, kitchens and society rooms’, hotels, school houses and college buildings, skating rinks, casinos, music halls and many others that give us cause to consider the architect’s expanded remit of the last two centuries.42 Pevsner lists a series of architectural histories of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that include ‘surveys of types which traditionally formed part of the architectural courses’, and a number of more recent studies to complement his own attempt to provide a first history of building types written as such.43 Carroll Meeks’s The Railroad Station (1956) is notable among his examples, as is Johan Friedrich Geist’s history of the nineteenth-century arcade, dating from 1969.44

9 Evolution of the temple type, Plate 1 of Les ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce, considérées du côté de l’histoire et du côté de l’Architecture, by Julien-David Le Roy, plate by Michelinot, after Le Moine.

Of course, Pevsner’s book does not exhaust the extent of architectural types, attending mainly to those of importance to architects of the nineteenth century. In the book’s foreword, though, he usefully observes that ‘this treatment of buildings allows for a demonstration of development both by style and by function, style being a matter of architectural history, function of social history’.45 Type, then, is in his presentation a combination of function, materials and styles, the histories of which intersect as a typological history informed by the demands made of architects by their clients and patrons, by the technical possibilities available to the architect, and by architecture’s internal artistic and conceptual developments.46

Most contemporary histories of architecture that follow cues of a typological nature do not do so in order to advance a strong theory of architectural genus. For most architectural histories type is a category of convenience that combines well with other framing devices. Michael Webb’s Architecture in Britain Today (1969) makes typological divisions in a history determined by geography and period, so that modern British architecture is further classified within a number of smaller genres: a series of educational and institutional types, houses and housing at various scales, shops and offices, sports venues and churches.47 Typological classification is not the end for which these histories are the means, but genre offers useful divisions to an otherwise unwieldy subject.

Igea Troiani’s history of the bank buildings of Australian architect Stuart McIntosh is clearly concerned with that type of work within McIntosh’s œuvre.48 She studies the evolution of his approach to the problem of designing banks, of reacting to client demands, of exploring the possibilities afforded by this kind of commission for his own thinking about architecture. These questions are thus partly biographical, partly contextual and partly periodic, relating to the history of modern architecture in general, and its Australian path in particular. Again, it would make little sense to insist on calling Troiani’s approach to architectural history typological, yet in her article on McIntosh’s banks she uses the tools of a typological division of architectural history, and of the architect’s biography, to manage a subdivision of the larger histories to which McIntosh’s case contributes.

To suggest, though, that a typological organization of individual architectural histories is often commonsensical, as in Webb’s book, is not to overlook more complex historiographical manoeuvres that are likewise predicated on a typological identification.

In Bouwen voor de Kunst? (2006), for instance, Wouter Davidts addresses a sub-genre of the museum type, the museum of contemporary art, while conducting a critique of typological and critical categories.49 Davidts’s book reverses a simplistic typological reading while upholding the ‘natural’ frame suggested by his subject. He acts against the tendency of architectural histories concerned with institutions to pay too little attention to the extra-architectural forces that help to shape the building. The art gallery is for him a building and an institution, and the programme of one shapes that of the other. Davidts’s study pays close attention to the workings and imperatives of art institutions while offering a historical account of the building types on which they rely.50 This counters the tendency among architectural histories to privilege the building above the institution – reflected, of course, in those institutional histories that regard architecture and architectural decisions as incidental to the functions and ambitions of the institution being housed.

Setting aside these observations concerning overtly typologically organized architectural histories, the vast majority of histories of architecture organized along typological lines treat the functional division of one building type from another much more pragmatically, where a type is a convenient way to limit a historical study rather than constituting a fixed and defensible unit.

Technique

Earlier in this book we encountered a basic failure of architectural historians to agree on what architecture has been, historically. As we have seen, this failure has allowed for vibrant discussions and important conceptual differences that have informed a broad and rich approach to the study of architecture’s past. The fact remains, though, that where some think that architectural history encompasses all building ascribed to human culture from all time, others treat it as a European tradition of mere centuries’ depth.

In the last essay published before his death, Reyner Banham considered how this problem gave rise to a historiographical premise: that there is something particular to architecture of which histories can be written. Or rather: one can write histories of the things that architects do that others do not.51 This latter distinction allows us to include proto-architects in this definition of a pretext for architectural historiography, which is to say, include those master-masons, sculptors or proti who would not have had the present-day concept of ‘architect’ available to them through historical circumstances. The question therefore becomes: what have architects done over time, which now defines them historically as architects, and their work as architecture, and of which histories can be written? Histories of this kind see coherence in the way that architects have put concepts into play over time, knowingly or not. Such histories as these might regard this as the basis of architecture’s disciplinarity, rendering productive the anachronistic application of the terms ‘architecture’ and ‘architect’ to buildings that, and individuals who, were not considered as such in their own time. It links the present to the past, and allows the historian of architecture to tell a story about architecture without the burdens of that term’s more recent history as a concept and an institution.

Following the lead offered by Michel Foucault, we can think of these architectural histories as histories of technique, where technique is a product of discourse. Architectural histories need not be Foucauldian in their approach or tenor to take advantage of the historical divisions that his thinking has allowed the last few decades of historiography: the history of technique within architecture, and of architecture as a technique.52

Consider, as examples of this broadly constituted approach, architectural histories of drawing, of tectonics, of construction, of designing for a world seen as if in pictures, of writing instructions for other architects (the Italian word trattazione best captures this technique), of ordering reality along architectural lines (the Italian, again, progettazione), or simply of making windows, doors, corners and pathways. These can equally be subject to such historicization as the long durational history of architecture allows. Giedion’s Space, Time, and Architecture (1941) is a model of this approach to writing history: identifying in their abstraction the values and activities of the modern architect and retrospectively constructing their history.53 His two-volume work The Eternal Present (1962) is likewise a classic instance of an art history of ‘space-making’, delving deep into Mesopotamian and Egyptian examples in order to activate a modernist teleology with a lengthy run-up.54 Giedion’s student Christian Norberg-Schulz offers a parallel example in his books Intentions in Architecture (1965), Existence, Space, and Architecture (1971) and Meaning in Western Architecture (1975).55 The technique with which these are concerned is ‘place-making’, a phenomenological concept that acquired significant currency and historical authority through Norberg-Schulz’s work. Whatever the stripe and tenor of the content of a history of technique in or as architecture, the historiographical mechanism of the longue durée owes a great deal to the trajectory of French historiological thought that spans from Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch to Foucault. In the hands of Giedion and Norberg-Schulz, to give two instances drawn from many possible examples, these technical histories are less histories of architecture than of practices. These are not always, and in fact are rarely, specific to architecture. And the identification of the ‘techniques’ of which these historians make histories is itself a product of history. These histories would be inconceivable outside of the moment in which they were written.

More recently, John Macarthur and Antony Moulis have argued for a history of plan-making (or architectural planning) as a basis for such a long-durational history of architecture. The plan, like any other technique in architecture, is a historically shaped construction of architectural historians. For architects to think planimetrically is not a given of architecture, but rather something acquired through transmission and habit. In a paper delivered to the 2005 conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand (SAHANZ), Macarthur and Moulis observe one of the complications of relating the history of the architectural plan to the history of architecture: ‘The plan has been an integral, general tool for architecture across diverging socio-historical circumstances, in which the concept of architecture has also varied greatly. It is difficult, then, to imagine a history of the plan that is premised on a solid concept of architecture.’56 Even to limit the history of architecture to a Western tradition, the qualifications, skills, knowledge, tasks and status of the figure of the architect have all changed dramatically over the centuries. Beyond a loose definition of ‘architecture’ as ‘the art or science of building’, there is no unified definition of the term that has survived changes in society, technology or institutions. Macarthur and Moulis thus ask, ‘what bases are there of a longitudinal history of architecture?’57

The plan offers an example of the kind of historical subject that might operate across other forms of historical change. It can be understood literally and conceptually. It can be found in drawings and diagrams as well as in buildings themselves. From a drawn plan the historian can extrapolate a ground plan of a building, either as a reality subject to scale or as a figure reacting to the experience of a building by its inhabitants. (The classic historical problem of this kind is to understand the building represented by Piranesi’s complex, multi-level plan of the fictional Ampio Magnifico Collegio of 1750.58) Conversely, from an extant building the historian can diagrammatize the building at scale or in abstraction. Colin Rowe’s famous historical comparisons of Renaissance and modern buildings in his essay ‘The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa’ are exemplary of this possibility.59

Historical knowledge of the plan operates between these two approaches. Planning forms a ‘technique’ of architecture that, while independent of the various contexts that shape any given plan (drawn or derived), can nonetheless learn from those historical contexts while overcoming the specificities of any building to understand how architecture has been sustained historically and historiographically. The plan therefore presents architectural history with the problem of whether this field of study is a branch of history or an expression of historical consciousness intimately tied to the work of architects.

10 Ampio Magnifico Collegio, by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, first published in his Opera varie di architettura, prospettive, grotteschi, antichità (Rome: Bouchard, 1750).

Whatever the larger conceptual implications of this choice might be, the architectural history of planning as conceived above describes the kind of approach to historical research and working that overcomes the historical specificities of architecture’s status as an art, craft, trade or profession, and thus positions continuities where other forms of history (framed by style, geography, architectural theory, society or culture) would recognize the historicity and the limitations of a general theory of architecture of which architectural historians could write histories. In this sense, the technique of planning sits alongside other techniques that have been treated historically. Each offers new filters for the subject of architecture while overcoming the limitations imposed by what we might understand as ‘classic’ historiographical tools and perspectives.

Theme and analogy

This sixth and final grouping of approaches to architectural historiography runs against the grain of the preceding headings. Whereas architectural history as the history of architectural style, type or technique relies on a historical continuity that can be constructed as internal to architecture, an architectural history organized along thematic or analogical lines references the relationships, concrete and abstract, between architecture and its ‘exterior’. A history of architecture organized thematically concerns coincidences between architectural activity and other kinds of historical activity, between buildings and the uses to which they are put or the significance they accrue, and it also engages the realm of architectural ideas and themes, such as inhabitation and representation, which themselves have repercussions well beyond architecture. Conversely, an analogous architectural history explores the conceptual devices available to architectural historians that allow that field to contribute new perspectives on issues beyond architecture, which once seemed beyond the architectural historian’s remit. How, such histories ask, is architecture analogous to technology and information systems, to politics, to society, to medicine and so on? Which of the architectural historian’s tools and techniques might usefully contribute to the study of those other fields?

Architectural histories organized along these lines align with the writing genre of late-twentieth-century architectural culture usually called architectural theory. Among thematic histories we would count those that identify architecture’s role in extra-architectural historical and theoretical themes, or the coincidence of architectural interests and developments with those beyond architecture. They are often recognizable by the pairing of the term ‘architecture’ with an external corollary: domesticity, language, the body, politics, religion, society, science, utopia, dystopia, hygiene, technology, advertising, consumption, memory, literature, film and so forth. The list is long, flexible and comprises a substantial bibliography that has dominated architectural publishing in recent decades. These histories treat the intersections and analogies to be found with and in the architectural subject. For histories conceived with these objectives in view, architecture becomes both evidence of the world of phenomena exceeding architecture itself and a player in that world.

This category might seem like a catch-all for those histories not easily associated with the preceding classifications and indeed it is the most difficult to isolate, since it opens out into a large number of disciplines beyond architecture and architectural history. Although there are indeed plentiful examples of thematic architectural histories, especially since the 1980s, they allow for an important conceptual distinction. If the longue durée history of architecture evidences a ‘technical’ or disciplinary consciousness, then thematic and analogous histories of architecture demonstrate an interdisciplinary consciousness whereby one understands where architecture sits in relation to its various physical and conceptual settings. Whereas technique concerns the core, theme and analogy pertain to the edges, and thus to the borders between architecture and other things.

An influential early example of such a thematized, theoretical architectural history is Tafuri’s Progetto e utopia (1973), which historicized and politicized the interaction of architecture and ideology after the Enlightenment.60 In addition to Tafuri’s own books on political and ideological themes, which concern settings as diverse as Vienna, the Soviet Union, Venice, Rome, the United States and Germany, a steady stream of publications have followed his cues or established new entries to this subject.61 It is reasonable that politics would present an early locus for thematic histories of architecture. A thematic approach, as it was first tested, had a political mission in relation to the traditional techniques for researching, organizing and writing architectural history.62 Organization along thematic lines permitted historians to account for evidence and analytical perspectives for which a history of style, for instance, or type simply did not allow. The historical studies presented in the American journal Oppositions (1973–84) explored many of the implications of this historiographical theme (alongside, notably, the theme of language). In its uptake of the Oppositions project, the later journal Assemblage (1986–2000) advanced this theme through its preoccupation with representation.

William J. Mitchell’s City of Bits (1995) might now seem naïve as a study in the architectural parallels offered by the ‘Netscape’ generation of internet life (‘Now, I just said that wjm@mit.edu was my name, but you might equally well [or equally inappositely] claim that it was my address’63). His book was, nonetheless, one of the first to open architectural theory to this theme, and to explore problems of the newly broadened experiences of networked life. It also offers a useful example of a strategic dislocation of architectural themes and theories from architecture qua architecture. Mitchell trades physical space for virtual space, studying the manner in which online communities were built and maintained in parallel to communities contingent on the occupation of land and three-dimensional space. Within a theoretical-critical approach he seeks to understand the nature of the infrastructure necessary to conduct business, communicate and otherwise interact virtually, all the aspects of a way of life that quickly became the norm. Positioned thus, architecture and its theory had a new role in bridging existing and emerging phenomena critically, theoretically and historically. Mitchell’s City of Bits might now be a historical record of this turn in its own right, sitting alongside Jean-François Lyotard’s Moralités postmodernes (1993) or Douglas Coupland’s Microserfs (1995) as evidence of a mid-1990s fascination with this techno-cultural theme.64 Importantly, though, Mitchell demonstrated the conceptual and historical availability of architecture and its lessons for problems beyond architecture.

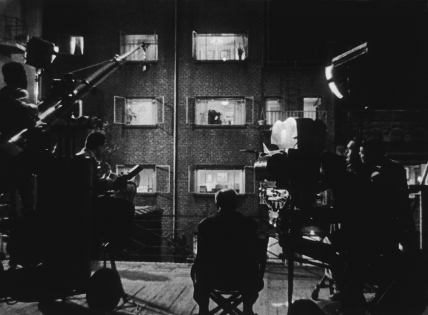

Other examples illustrate how architecture and the tools of its historians offer new takes on existing themes. Dietrich Neumann’s book Film Architecture (1999) explores the cross-pollination of the two terms of his title over the lifespan of modern film. Steven Jacobs pushes this theme further in his study The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock (2007), where modern architecture and the Hitchcock filmography together consider the themes of psychology and space along historical and critical lines, and within the history of techniques of cinematic production.

A number of anthologies have, similarly explored questions of gender in architectural history: Sexuality and Space, The Sex of Architecture and Stud, to name some 1990s classics.65

11 Jeffries apartment and courtyard, West 10th St, Greenwich Village, New York, depicted in Rear Window, directed by Alfred Hitchcock (1954). Production photograph.

None of these books’ editors or authors would unconditionally position these as volumes of architectural history, especially given their shared mission to open up knowledge of the canon with the tools developed by post-structuralist and postcolonial theory imported into the historiography of architecture and theorization of historical architectural works and themes. As a result, these works and themes definitively extend their historical subjects by the use of new critical and theoretical perspectives, all the while cutting through the chronological divisions established and maintained in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Architectural histories that take their subjects as participants in a broader, extra-architectural theme, or that offer analogies with other historical phenomena, can extend the canon by reinstalling figures and works overlooked and then forgotten by previous critics and historians of architecture. They often do this by addressing an existing canon with new analytical tools that render an established historical subject even more complex, thereby valorizing its importance while questioning the mechanisms of the canon itself.

Doubtless there are further approaches to the problem of organizing the past of architecture into historical units to which I could devote space here. Some of the choices available to contemporary historians of architecture have endurance on their side; others are relatively new, bound to the increasingly relativist and contextualist tendencies of all kinds of historiography during the latter part of the twentieth century. As strong strategies, they are all subject to intellectual fashion. As softer frameworks or approaches to the writing of architectural history, tempered one by another, or by others, they describe a good number of the organizational devices used by historians to convert the vast, heterogeneous past of architecture into coherent histories. Where this chapter has considered the terms on which historians can enact this translation, the next will turn to the stuff of that past. What of the past survives to the present as the material of architectural history? We are speaking now of the content of architectural history, and inevitably, therefore, of its relation to evidence.

Notes

1 Johann Gottfried Herder, Reflections on the Philosophy of the History of Mankind, trans. Frank E. Manual ([1784–91, 4 vols.] Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1968), esp. 79, in ‘Humanity the End of Human Nature’. Compare Peter Kohane, ‘Interpreting Past and Present: An Approach to Architectural History’, Architectural Theory Review 2, no. 1 (1997): 30–7.

2 Carl Albert Rosenthal, ‘In What Style Should We Build?’ in In What Style Should We Build? by Heinrich Hübsch, Rudolf Wiegmann, Carl Albert Rosenthal et al., trans. & ed. David Britt ([1829] Los Angeles: Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1992), 114.

3 George Selwyn, ‘Parish Churches in New Zealand’, Ecclesiologist (1841), cited in Robin Skinner, ‘Representations of Architecture and New Zealand in London, 1841–1860’, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Auckland, 2007, 163–224, 168.

4 As a symptom, see Jean Étienne Casimir Barberot, Histoire des styles d’Architecture dans tous les pays, depuis les temps anciens jusqu’à nos jours, 2 vols. (Paris: Baudrey et cie, 1891).

5 For a longer list of additional anthologies, monographs and themed issues of journals concerned with approaches to architectural historiography, see the ‘Further reading’ section.

6 Mark Roskill, What is Art History? 2nd edn ([1976], London: Thames and Hudson, 1989).

7 W. Eugene Kleinbauer and Thomas P. Slavens, Research Guide to the History of Western Art (Chicago: American Library Association, 1982).

8 Laurie Schneider Adams, The Methodologies of Art (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1996).

9 Michael Podro, The Critical Historians of Art (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1982).

10 Otto Pächt, Methodisches zur kunsthistorischen Praxis, ed. Jorg Oberhaidacher, Arthur Rosenauer & Gertraut Schikola (Munich: Prestel, 1986); Engl. edn, The Practice of Art History: Reflections on Method, trans. David Britt (London: Harvey Miller, 1999).

11 James S. Ackerman, ‘Style’, in Distance Points: Essays in Theory and Renaissance Art and Culture (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1991), rev. from ‘A Theory of Style’, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 20, no. 3 (1962): 227–37.

12 Ackerman, ‘Style’, 3.

13 Ackerman, ‘Style’, 3–4.

14 Ackerman, ‘Style’, 4. Artistic style has been subject to much theorization. See, for example, Beryl Lang, The Concept of Style, rev. edn ([1979], Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1987); Caroline van Eck, James McAllister & Renée van de Vall (eds.), The Question of Style in Philosophy and the Arts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995); Andrew Benjamin, Style and Time (Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 2006).

15 Compare David Summers, ‘Art History Reviewed II: Heinrich Wölfflin’s “Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe”, 1915’, Burlington Magazine 151, no. 1276 (July 2009): 476–9.

16 Peter Gay, Style in History (New York: Basic Books, 1974), 7.

17 Ackerman, ‘Style’, 4.

18 Ackerman, ‘Style’, 4–5.

19 Émile Bayard, L’Art de reconnaître les styles (Paris: Librairie Garnier Frères, 1900).

20 François Benoit, L’Architecture, Manuels d’histoire de l’Arte, 4 vols. (Paris: Laurens, 1911).

21 On this problem, see Mark Crinson & Claire Zimmerman (eds.), Neo-avant-garde to Postmodern: Postwar Architecture in Britain and Beyond, Yale Studies in British Art 21 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2010).

22 Ethan Matt Kavaler, ‘Renaissance Gothic: Pictures of Geometry and Narratives of Ornament’, Art History 29 (2006): 1–46. A conference at the Institut national d’histoire de l’Art (Paris, 12–16 June 2007) considered this pairing in some detail under the title ‘Le Gothique de la Renaissance’.

23 This point draws on comments made to me by John Macarthur, who has served in this capacity. Compare Paul Walker & Stuart King, ‘Style and Climate in Addison’s Brisbane Exhibition Building’, Fabrications 17, no. 2 (December 2007): 22–43, esp. 23–8.

24 Arnold Hauser, Social History of Art, 4 vols. ([1951– ], London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962); and Philosophy of Art History (London: Routledge; New York: Knopf, 1959), esp. ‘Wölfflin and Historicism’, 119–39.

25 See, for example, Charles Burroughs, From Signs to Design: Environmental Process and Reform in Early Renaissance Rome (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990); Manfredo Tafuri, Venezia e il rinascimento. Religione, scienza, architettura (Turin: Einaudi, 1985); Engl. edn, Venice and the Renaissance, trans. Jessica Levine (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995) – compare Tafuri, Humanism, Technical Knowledge and Rhetoric: The Debate in Renaissance Venice (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Graduate School of Design, 1986); Deborah Howard, Venice and the East: The Impact of the Islamic World on Venetian Architecture, 1100–1500 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2000).

26 Hessel Miedema, ‘On Mannerism and maniera’, Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 10, no. 1 (1978–9): 19–45. Compare the panel dedicated to this theme and chaired by Ernst Gombrich, ‘Recent Concepts of Mannerism’, in Studies in Western Art: Acts of the Twentieth International Conference of the History of Art, vol. II, The Renaissance and Mannerism, ed. Ida E. Rubin (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963), 163–255. This included contributions by Craig Hugh Smyth, John Shearman, Frederick Hartt and Wolfgang Lodz. Franklin W. Robinson & Stephen G. Nichols, Jr (eds.), The Meaning of Mannerism (Hannover, NH: University Press of New England, 1972). Compare Craig Hugh Smyth, Mannerism and Maniera (Locust Valley, NY: J. J. Augustin, 1962) and John Shearman, Mannerism (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1967).

27 Antonio di Tuccio Manetti, The Life of Brunelleschi, ed. Howard Saalman, trans. Catherine Enggass (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1970).

28 Compare Focillon’s observation in La vie des formes that the division of historical time by century lends the century itself a biographical character.

29 Terrence Riley & Barry Bergdoll (eds.), Mies in Berlin (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2001); Phyllis Lambert (ed.), Mies in America (New York: Harry S. Abrams, 2001).

30 Marco De Michelis, Heinrich Tessenow, 1876–1950 (Milan: Electa, 1993); Claude Laurens, Architecture. Projets et réalisations de 1934 à 1971, ed. Johan Lagae, Vlees en Beton 53–4 (Ghent: Vakgroep Architectuur en Stedenbouw, Universiteit Gent, 2001).

31 One recent book that attends to this complexity from the perspective of a New Zealand case is Justine Clark & Paul Walker, Looking for the Local: Architecture and the New Zealand Modern (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2000). For Clark and Walker, New Zealand architects operate between processes of reception and invention, and the idea of the local enters a relationship with the anti-local.

32 Compare Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, Toward a Geography of Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

33 G. E. Kidder Smith, Switzerland Builds: Its Native and Modern Architecture (London: Architectural Press; New York & Stockholm: Albert Bonnier, 1950), 21. See also Giedion’s introductory essay, ‘Switzerland or the Forming of an Idea’, 11–17.

34 Jul Bachmann & Stanislaus von Moos, New Directions in Swiss Architecture (London: Studio Vista, 1969), 11.

35 Eberhard Hempel, Baroque Art and Architecture in Central Europe: Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland. Painting and Sculpture: Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries; Architecture: Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries, trans. Elizabeth Hempel & Marguerite Kay (Harmondsworth: Pelican, 1965).