Some killers prepare for their big event by doing what they believe is necessary to occupy the center of attention nationally, if not around the world. These killers want to make the headlines, dominate the nightly news, and grace the cover of magazines—they want to go down in infamy. Charles Manson, who remained incarcerated decades after his role in the murders of seven people over two nights in 1969, once remarked that he was the most famous person who had ever lived. Thanks to the omnipresent news media coverage of Manson and his “family” throughout the decades, that may be only a slight exaggeration.

Yet, having a prominent position in popular culture is only one of the ways in which murderers can experience a surge of power. Some killers achieve feelings of dominance and control by “playing God” with the lives of their victims or causing tremendous pain and suffering, while others enjoy outsmarting police in a cat-and-mouse game. Still others get a high from terrifying an entire community, knowing that their frightening and unpredictable attacks have disrupted the mindset of a majority of the population.

In the planning stage, some killers construct the materials that will outlive their own mortality to give them a prominent place in history. They write diaries, manifestos, and autobiographies; they take photos and record video depicting an image of themselves by which they want to be remembered; and they communicate with police and members of the press. After a life lived in relative obscurity, poverty, or pain, they believe that they now have a chance to be important—to ensure that no one ignores, rejects, or harasses them ever again. For the first time in their lives, they feel special, perhaps like an anti-hero or celebrity who captures the attention of millions of people (Fox and Levin 2018; Lankford 2016; Wiest 2011).

Many serial killers have recognized the news media as an available outlet for fame, and some have intentionally sought recognition through media coverage. Keith Jesperson, a Canadian-American serial killer who murdered at least eight women in the 1990s, sent numerous letters to media outlets, both before and after he was apprehended. So did Dennis Rader, the notorious killer known as BTK (the letters described the killer’s modus operandi: “bind,” “torture,” and “kill”) who murdered ten people in Kansas from 1974 and 1991, as well as David Berkowitz, the so-called “Son of Sam” who killed six people in New York City in the mid-1970s.

Some killers have commented on the immense attention they receive even after they are convicted. After Rader confessed to his crimes in court, he said, “I feel like a star right now” (Smith 2006, p. 305). Ted Bundy, another serial killer who murdered dozens of women across the United States during the 1960s and 1970s, described himself like a celebrity even when he was a prisoner, saying, “They all want to see Bundy. A lot of ‘em do. ‘Where’s Bundy?’ I’ll hear. ‘Let’s go see Bundy.’ They’ll drift by. There’ve been a lot of ’em” (Michaud and Aynesworth 2000, p. 294).

Even in his early eighties—decades after his crimes—Manson continued to receive letters and phone calls from adoring fans. He sold his music online, where he also advertised the mission of an environmentalist program titled ATWA (an acronym for air, trees, water, and animals). Manson died of natural causes in 2017, but his name remains entrenched in the memories of generations of Americans. Manson likely will join the likes of departed killers Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer (who killed seventeen people, cannibalizing some of them, in Milwaukee from 1978 to 1991), whose names continue to appear in the press long after their deaths. (Bundy was executed in 1989, and Dahmer was murdered in prison in 1994.)

Oftentimes, infamous killers’ names are used as a kind of yardstick by which other apparently “bad people” can be measured. For example, the first line of a 1998 Associated Press story about filicidal mother Marie Noe compares her to Bundy: “A 69-year-old woman accused of killing eight of her infant children is a mass murderer just like Ted Bundy and should not be allowed back on the streets, prosecutors argued” (Hoffman 1998). More recently, an August 2017 airing of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert referenced Dahmer in a joke about U.S. President Trump receiving a compliment from a notorious white supremacist: “David Duke complimenting your courage—that’s like Jeffrey Dahmer complimenting your cooking. He means well, but it’s a little upsetting” (Hoskinson 2017). When a comedian includes the name of a person in a joke intended for a general audience, it’s safe to assume that the person is considered a household name.

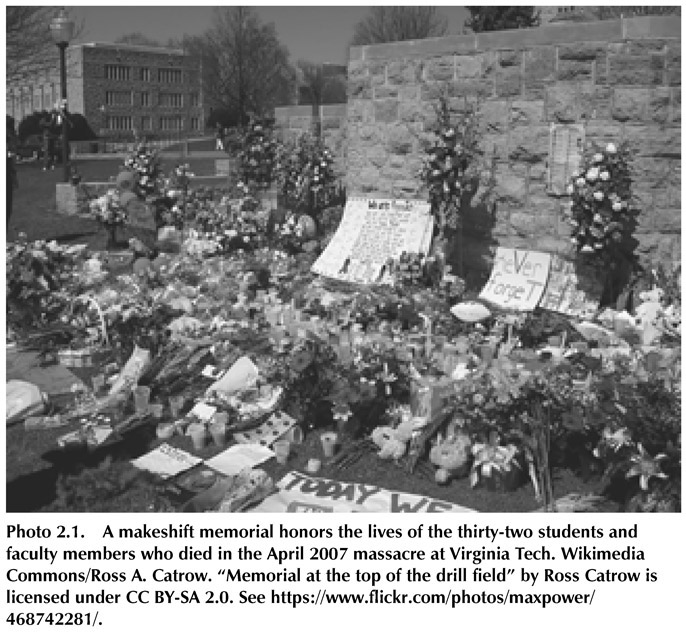

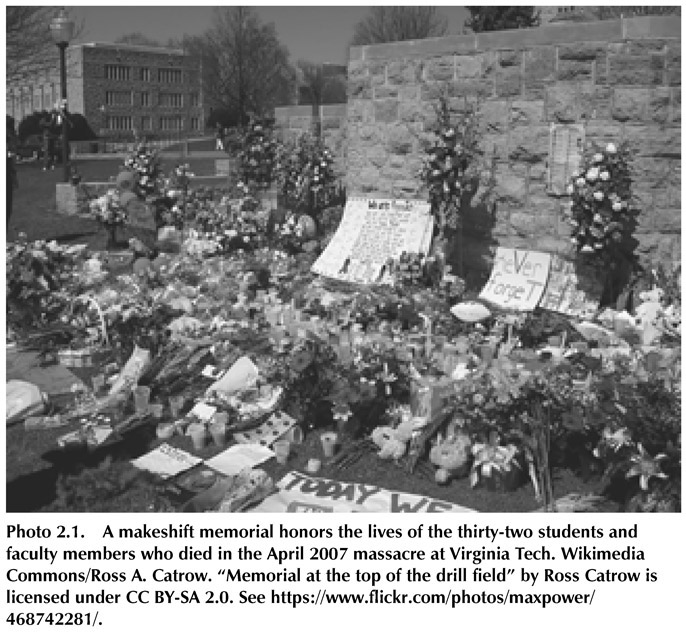

Some killers see the commission of murder as an opportunity to move from obscurity and ostracism to a position of immense importance, even posthumously. In April 2007, Seung-Hui Cho was a senior at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University and set to graduate in a few weeks. Instead of feeling excited or anxious, though, he was filled with rage—sick and tired of being mistreated by fellow students. He had been bullied, teased, and rejected throughout middle school and high school, and he thought his college classmates turned out to be no better than their younger counterparts. After being treated like “a piece of garbage” for too long, Cho was ready to show everyone just how powerful he could be. The subsequent Virginia Tech massacre perpetrated by Cho resulted in the deaths of thirty-two students and faculty members.

The killer’s preparations began in early February 2007, when he stopped at a pawnshop located across the street from campus and purchased a Walther P22, a relatively inexpensive semi-automatic pistol commonly used for target practice. Later that month, Cho bought ammunition at a local Walmart. In March, he purchased a semi-automatic Glock 19 pistol with a high-capacity magazine capable of holding thirty-three bullets, as well as fifty rounds of ammunition, at a Roanoke gun store. With weeks left before he would implement his plan, Cho practiced his marks-manship at a local firing range, worked on his body strength and stamina at the gym, and continued to attend classes.

During this time, Cho was also busy assembling the elements of his “press kit,” which included twenty-three pages of photographs and text, as well as forty-three videos he recorded of himself. In the videos, Cho posed with the two handguns, a knife, and a hammer—at times aiming the weapons threateningly at the camera and at himself—while discussing his reasons for the impending attack. He also rambled about his hatred of religion and wealthy people. In one of the videos, Cho spoke directly into the camera to address those he blamed for pushing him too far: “You had a hundred billion chances and ways to have avoided today. But you decided to spill my blood. You forced me into a corner and gave me only one option. The decision was yours. Now you have blood on your hands that will never wash off.”

Cho’s 1,800-word, obscenity-laced manifesto (Langman 2017) reiterates his contention that his fellow students on campus had caused their own demise by their severe mistreatment of him. He wrote, “As the time approached, I wished for a last minute miracle and discard this mission you’ve given me. Heaven knows I wouldn’t hurt a single leaf of a flower. But when the time came, I did it. I had to. What other choices did you give me?” Cho’s writing also made it abundantly clear that he hoped his actions would inspire other would-be mass murderers. He saw himself as a powerful leader of Biblical proportions. He even literally compared himself to a divine being at one point, writing: “Thanks to you, I die, like Jesus Christ, to inspire generations of the Weak and Defenseless people—my Brothers, Sisters, and Children—that you fuck. Like Moses, I spread the sea and lead my people—the Weak, the Defenseless, and the Innocent Children of all ages that you fucked and will always try to fuck—to eternal freedom.”

On the morning of his April attack, Cho first shot to death two people in the West Ambler Johnston Hall residence hall. He then walked across the street to a post office, where he mailed his multimedia press kit—including the written manifesto, videos, and photographs—to NBC News, hoping that the media outlet would release its contents to the public. Next, about two hours after the first shootings, he entered Norris Hall, an academic building with classes in session, and chained shut the three main entrance doors. He then went from classroom to classroom, opening fire on students and faculty members. In the span of about ten minutes, he took the lives of thirty people and injured another seventeen. He then turned the Glock pistol on himself and committed suicide. The massacre was immediately declared to be the deadliest shooting by a lone gunman in U.S. history, establishing the record that Cho had badly wanted. Days later, NBC News released his press kit, assuring that Cho will take his place among the most notorious killers of his time.

It is conceivable that certain serial and mass killers who seek to go down in infamy are very much aware of previous murderous episodes and are motivated to set new records. They might regard their large body count as a tremendous accomplishment, rather than a hideous crime. Thus, it may not be a coincidence that the October 1991 massacre at Luby’s Cafeteria in Killeen, Texas, took the lives of exactly twenty-three patrons having lunch. In the aftermath, investigators who searched killer George Hennard’s home discovered that the 35-year-old had recently viewed a videotaped version of James Huberty’s 1984 mass murder at a fast-food restaurant in San Ysidro, California. In that incident, Huberty killed twenty-one customers and employees—just two fewer than attributed to Hennard.

A notorious Canadian multiple murderer, Clifford Olson was responsible for the murder of eleven children and young adults during the early 1980s. But, in an effort to achieve the status of the most prolific killer in recorded history, Olson was known to falsely confess to a number of other murders he had not actually committed. In most cases, he was securely incarcerated at the time the killings took place, making his participation in them all but impossible. As further illustration of his obsession with notoriety, while an inmate in Kingston Penitentiary, Olson would insist that his visitors refer to him as Hannibal Lecter, the fictional character featured in several novels and films who was a brilliant psychiatrist and cannibalistic serial killer.

The media’s habit of touting “records” related to heinous crimes—such as “worst mass shooting in U.S. history”—may give would-be killers something to strive for. In June 2016, 29-year-old Omar Mateen shot to death forty-nine patrons and injured fifty-eight others at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando before he was killed by police. By then, though, Mateen had already amassed the largest body count of any mass shooter in U.S. history at the time, and news media were quick to point it out. That record lasted just over a year. In October 2017, 64-year-old Stephen Paddock shot to death fifty-eight country music concert-goers on the Las Vegas Strip, aiming from the smashed window of his room on the 32nd floor of the Mandalay Bay Hotel, and the media once again swiftly named the new titleholder. For those keeping track, the number of fatalities in the worst of recent mass murder cases has increased dramatically.

Another approach employed by some killers who are desperate to feel powerful involves deciding who will live and who will die. Serial killer Ted Bundy took the lives of dozens of women during the 1960s and 1970s in states including Utah, Washington, Colorado, Michigan, and Florida. Before embarking on his killing spree across the country, however, Bundy worked on a suicide hotline in Seattle, where he took calls from profoundly depressed individuals who were on the verge of killing themselves. In addition, Bundy once rescued a 3-year-old boy who was drowning in Seattle’s Green Lake after the boy’s parents momentarily took their eyes off of him. Saving lives and taking lives—for some killers, they are two sides of the same coin, both offering similar feelings of power, control, and dominance. Unfortunately for Bundy, his good deeds never figured into jury sentencing decisions.

Many killers are selective in their choice of victims, opting to murder only those they hold responsible for their personal problems. For example, 42-year-old Michael McDermott in December 2000 shot to death seven co-workers at his Edgewater Technology worksite in Wakefield, Massachusetts, after the company began garnishing his wages to the IRS for unpaid taxes. A day before opening fire at work, he stored weapons under his desk, including an automatic rifle (a variant of the AK-47), a shotgun, and a handgun. The next day, McDermott walked around his workplace directing deadly gunfire only at employees in human resources and the payroll office whom he believed were conspiring against him, while sparing the lives of many others. McDermott was eventually convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison without parole.

Nearly all serial killers derive satisfaction from overpowering and controlling their victims. In fact, most target victims they believe can be manipulated relatively easily. The most-common victims of serial killers are members of vulnerable populations—including prostitutes, runaways, children, the elderly, and members of ethnic minority groups—who have less ability or fewer resources to resist. When serial killers do target members of higher-status groups, they often use methods that afford a larger amount of containment. Unlike torture, which is often an end in itself, their weapon distances them from their victims but is the means to an end. For example, Aileen Wuornos, who killed seven men in Florida from 1989 to 1990, used a firearm (in contrast to more common methods employed by serial killers like strangulation and stabbing), and she also relied on the element of surprise.

Further, serial killers frequently bind their victims before killing them, affording a large amount of control. Jeffrey Dahmer took the idea of control to an extreme, as he drilled into the skulls of some of his victims and poured acid inside in hopes of turning them into zombies that he could use as sex slaves and control indefinitely. Some refer to victims as their “property” or “possessions” and describe a sense of loss when victims’ bodies are discovered and removed from their dump sites (Wiest 2011). Others describe a desire to regain power that they feel has been taken from them. For example, Robert Berdella, who murdered at least six men in the 1980s, described how it felt when he tortured and killed a victim in this way: “Possibly the way I handled situations prior to this, I saw myself in a weak state. This was a way where I was no longer weak and helpless” (Jackman and Cole 1992, p. 257).

Serial killers who value their capacity for control sometimes permit certain victims to escape with their lives. In Pasadena, Texas, 15-year-old Rhonda Williams was elated when her 17-year-old friend Elmer Wayne Henley offered to help her escape the abuses of her alcoholic father. In August 1973, Henley brought Williams to the residence of his older companion, Dean Corll, thirty-three. Little did Williams know that her good friend was an accomplice of Corll, who had sexually abused, tortured, and murdered at least twenty-eight boys and young men. Henley and another teenage accomplice, David Brooks, would help lure victims to Corll’s residence, receiving $200 for each one.

At Corll’s house, Williams partied until she passed out. Upon waking, she found herself bound hand and foot, alongside Henley and another male teenager. Corll was furious that Henley had brought a girl to his house and ordered him to torture and kill Williams while he did the same to the other teenager. When Henley agreed, Corll untied him, and together they brought the two teenagers into Corll’s bedroom. As Corll began attacking his victim, Henley grabbed a gun that was lying nearby and shot him to death. In the process, he saved the lives of Williams and the other captive. When push came to shove, Henley was able to separate himself from his sadistic companion to do the right thing. He realized that he did not have to comply with Corll’s dictates; instead, he took charge and decided who would live and die that night. Henley then turned himself in to police and confessed to his role in six of Corll’s murders. Both Henley and Brooks are serving life terms in prison.

Sadistic killers feel a tremendous surge of power when they torture their victims. The louder their victims scream and the more they beg for mercy, the better these killers feel about themselves. It is usually not enough for sadistic murderers to witness the torture; they must exercise total control using their own hands to brutalize a victim. For this purpose, firearms usually won’t do, as they tend to feel too detached or impersonal. In many cases, sexual desire serves as the vehicle for sadistic killers’ feelings of power and control. In order to feel pleasure, though, they must inflict pain and see their victim’s terror first-hand in an up-close-and-personal manner.

In January 2013, from the bedroom of his modest West London home, 58-year-old Peter Fasoli begged for his life as he was attacked by a phony police officer during sexual role play, while a radio broadcasting classical music droned in the background. Fasoli had met his companion, 28-year-old Jason Marshall, through a gay dating app, and the two arranged their first encounter for that evening. Shortly after Marshall arrived, however, he stopped being flirtatious and friendly. Instead, he threatened Fasoli with a large knife and forced him to hand over his debit card and PIN. Then, Marshall tied him up, gagged him, and tortured him for six brutal hours. At one point, he smothered Fasoli with cling wrap while he gasped for air and begged to be released. The killer finally placed a plastic bag over his victim’s head and held it there for exactly one minute and forty-two seconds. Assuming his victim was dead, Marshall then calmly smoked a cigarette, set the place on fire, and walked out the door.

A pathologist later determined that Fasoli ultimately died from smoke inhalation—apparently he was unconscious but not dead when the killer left—and it was ruled an accidental death. Nearly two years passed before anyone realized that this was no accident. In November 2014, Fasoli’s nephew was examining his uncle’s fire-damaged computer as part of a genealogy project when he discovered a shocking seven-hour video. Incredibly, Fasoli—apparently intending to secretly record the anticipated sexual encounter—had set up a webcam that wound up recording the entire horrific crime.

By this time, Marshall had been incarcerated for several months in an Italian prison. After killing Fasoli, he had used the victim’s debit card to buy a plane ticket to Rome. Just a few weeks after arriving, he killed another man he met through the dating app, 67-year-old Vincenzo Iale. About a week after that, he tried to kill a third man, 54-year-old Umberto Gismondi, but fled after his victim was able to alert his neighbors to the attack. In July 2014, Marshall was convicted in an Italian court of murder and attempted murder and sentenced to sixteen years in prison.

British police then arranged with their Italian counterparts to have Marshall extradited back to London to face the murder charge in Fasoli’s death. Once he was shown the video, Marshall admitted that he did it but claimed to have no memory of the incident. Nevertheless, he was convicted and sentenced to life in prison with a minimum requirement of thirty-nine years served.

Jason Marshall was clearly obsessed with a need for power. Not only did he thoroughly enjoy controlling the bodies and lives of the men he tortured, but he regularly impersonated authority figures because it made him feel powerful. According to a news report about the British trial: “When asked about impersonating a police officer, he said he had been arrested ‘many, many times’ because of it but he did it because he liked the ‘respect’ the uniform gave him” (BBC News 2017).

Another method that killers have employed to enhance their feelings of power and dominance is to play a cat-and-mouse game with the police. Serial killers are particularly likely to strategically toy with authorities, especially if they have managed to stay on the loose for long periods of time. Despite taking multiple lives over a period of months or even years, they still may not even be a suspect. When they look over their shoulder, there is no homicide detective. Looking over their other shoulder, there is no FBI agent in sight.

For some longtime multiple murderers, the killing spree may begin to lose much of its ability to inspire a sense of dominance and control. Murder doesn’t have quite the same effect as it used to, and they may have become bored. After all, it is far more satisfying to win a game played against a worthy opponent. Convinced of their superiority over both victims and law enforcement, these killers may decide to start communicating with police—taunting them, daring them to get close, and maybe even leaving cryptic clues behind at murder scenes. Oftentimes, the killer will attempt to contact the police through the news media in hopes of taunting authorities while gaining some publicity at the same time. Dennis Rader, the BTK serial killer, did just that during the early years of his murder spree that took the lives of ten people in Wichita, Kansas, and he did it again more than a decade after he stopped killing.

Rader’s first act of murder resulted in the deaths of four people in January 1974 and nearly took the lives of an entire family, including a 38-year-old husband and father, a 33-year-old wife and mother, a 9-year-old boy, and an 11-year-old girl. The only family member to survive was a 15-year-old boy, who was only spared because he had already left for school the morning of the attack. He also was the first to discover the horrific scene when he arrived home that afternoon, an image that undoubtedly will haunt him for the rest of his life. A few months later, BTK struck again, killing a 21-year-old woman in her home and nearly killing her brother. He didn’t kill again until 1977, when he took the lives of two women in separate attacks several months apart. Then he took another several years off from murder.

From 1974 to 1979, however, Rader sent taunting letters from BTK to police and news media outlets. In some, he threatened to kill more people if he didn’t see sufficient coverage of his murders in the newspapers and nightly news broadcasts. Then the correspondence suddenly stopped. No additional letters came even when he began killing again, taking three more women’s lives from April 1985 to January 1991. At that point, Rader had killed a total of ten people—men, women, and children—and he apparently never killed again.

More than a decade passed without authorities hearing from BTK; there had been no more murders attributed to him and no more taunting letters. Most people assumed the killer was either dead or in prison. But then, in 2004, BTK resurfaced. He began contacting local media again and providing evidence of his complicity in the unsolved murders. Rader still harbored an intense desire for publicity, as he later admitted that the impetus for his reemergence was that he heard someone was writing a book about the BTK murders and simply could not allow someone else to tell his story.

In March 2004, reporters at The Wichita Eagle newspaper received a letter from “Bill Thomas Killman,” an anonymous writer with not-so-subtle initials who claimed responsibility for the death of a local woman whose case was unsolved. The letter-writer also enclosed crime scene photographs and a copy of the victim’s driver’s license as proof. Two months later, a local television station received a letter that included chapter titles for “The BTK Story” and a word puzzle that purported to contain clues to the killer’s identity. In December 2004, Rader left a package for the police in a Wichita park containing the driver’s license of another BTK victim, as well as a doll with its hands and feet bound and a plastic bag tied over its head. Although Rader hadn’t killed anyone in years, he clearly enjoyed the superiority he still felt over police, who were unable to capture him after all that time. Taunting them with that fact now only increased his satisfaction and sense of power.

Finally, in February 2005, Rader made a huge mistake. After asking police if a computer disk could be traced back to its owner—they falsely told him no—he sent his next correspondence on disk to a local news station who then turned it over to law enforcement. Unbeknownst to the killer, police investigators were able to find details in the saved document that revealed the source as “Christ Lutheran Church” and the writer as “Dennis.” Armed with that information, it didn’t take long to find an individual named Dennis Rader, who happened to be president of the church council at Christ Lutheran Church. BTK was caught at last.

In June 2005, when his trial was supposed to begin, Rader decided to plead guilty and offered detailed descriptions of all ten murders; he showed no remorse and made no apologies. He received ten consecutive life sentences for his crimes and currently serves his time in solitary confinement for his own protection.

A decade before BTK, a serial killer calling himself the “Son of Sam” was targeting young adults, taunting police, and generally terrorizing New York City. The killer, David Berkowitz, shot to death six people and wounded another eight from July 1976 to July 1977, but most of his enjoyment appeared to come from the attention he received from the police and news media. Berkowitz left handwritten letters at his crime scenes and sent others to news media that took credit for the murders, mocked law enforcement’s inability to capture him, and promised further killing.

One letter he addressed to NYPD Captain Joseph Borrelli closed with the following words: “To the people of Queens, I love you. . . . May God bless you in this life and in the next and for now I say goodbye and good night. Police—Let me haunt you with these words: I’ll be back! I’ll be back! To be interrpreted (sic) as—bang, bang, bang, bank (sic), bang—ugh!! Yours in murder Mr. Monster.” In another sent to Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin, he included the following postscript: “JB, Please inform all the detectives working the case that I wish them the best of luck. ‘Keep ’em digging, drive on, think positive, get off your butts, knock on coffins, etc.’ Upon my capture, I promise to buy all the guys working the case a new pair of shoes if I can get up the money.” Referring to the columnist by his initials, asking him to relay a message, and promising a favor to detectives are all obvious attempts by Berkowitz to demonstrate the power and control he believed he held.

Other content in the letters appeared to offer some kind of explanation for the murders. Berkowitz often wrote about someone he called “father Sam” or “Papa Sam,” who he said controlled him and commanded him to kill. In a letter he sent to a journalist, he wrote, “When father Sam gets drunk he gets mean. He beats his family. Sometimes he ties me up to the back of the house. . . . Papa Sam is old now. He needs some blood to preserve his youth.” These references are likely meant to support his later contention that it was his neighbor’s dog—which he said was actually a demon—that operated through him as the “son of Sam.” (Years later, Berkowitz admitted that the demon-dog story was nothing but “a hoax.”)

When Berkowitz was finally arrested, he readily confessed to the crimes. After being found competent to stand trial, he pled guilty and, in June 1978, received six sentences of twenty-five years to life in prison—one for each murder. The sentences were meant to run consecutively but still granted eligibility for parole after twenty-five years. He has so far been denied parole every two years since his first hearing in 2002.

It isn’t only political and religious extremists who terrorize communities. Knowing that a serial killer is on the loose is often enough to throw an entire population into a state of panic. Many serial killers, especially those who hold a steady job, have a spouse and children, or otherwise appear to be an ordinary person, will closely follow news coverage of their crimes. The larger their body count, the greater the likelihood that they will receive national publicity and live in (secret) infamy. Publicity is, in the killer’s mind, nothing but pure power.

From June 1962 to January 1964, the Boston Strangler was on the loose, entering the apartments of women across Boston and its suburbs on the pretense of being a maintenance man who had been called to do repairs. Thirteen women opened the door to their apartments and all of them lost their lives. The first six victims were older women, most sixty-five and over, who lived alone in the city. The rest of the victims, though, tended to be much younger, typically women between ages nineteen and twenty-three. During this time, Boston was awash in collective anxiety. Women would not walk alone after dark, and female college students kept their doors double-locked. Some residents bought pepper spray for protection, and others left the city entirely. Conversations were filled with speculation about the identity of the killer and the likelihood of his apprehension. In other words, Boston’s residents were terrified.

Eventually, 33-year-old Albert DeSalvo confessed to committing the Strangler murders and in 1967 was sent to the maximum security prison in Walpole, Massachusetts, to serve a life sentence. Six years later, he was stabbed to death in the prison infirmary by an unknown assailant, and no one was ever convicted of his slaying. Many people, including some renowned criminologists, long believed that the wrong man had been convicted for the Strangler murders. Some even believed that there had been more than one killer. But fifty years after the murders, crime scene investigation techniques had vastly improved and were used to match DeSalvo’s DNA to seminal fluid recovered at the site of the Strangler’s last victim, 19-year-old Mary Sullivan. It is now known for certain that DeSalvo committed at least one of the brutal murders—and probably all of them.

On the other side of the United States about twenty years later, Californians were terrorized by Richard Ramirez, a rapist and serial killer the news media had dubbed “the Night Stalker,” who began killing in the Los Angeles area in 1984. Ramirez took the lives of thirteen people, but the manner of his criminal activities impacted hundreds of thousands more. The avowed Satanist would invade the residences of his victims, usually while they were asleep in bed or relaxing after work. He climbed through windows and hid in closets, striking when the residents least expected it. He made most pledge loyalty to Satan and beg for their lives. He stole items from the homes and left drawings of pentagrams on the walls.

The man who considered himself an all-powerful “servant of Satan” appeared to receive the most pleasure from the terror he inflicted on his victims and the entire community. That is likely why he allowed several victims to live, a highly unusual act for killers who want to avoid capture. For Ramirez, it was more important for his victims to recount in detail all of the brutal acts of torture he inflicted on them—so that they would have to relive it and so that others across the region would live in a constant state of fear and anxiety in their own homes. That did happen, of course. Residents all over the Los Angeles area were so terrified that they modified their lifestyles in any way they thought might reduce the possibility of becoming the next victim of the Satanic madman. They moved furniture against doors after dark, double locked their windows, slept with the lights on, and only left the house during the daylight hours.

By the summer of 1985, 25-year-old Ramirez, who had been closely following news coverage of his crimes, realized that law enforcement officers were starting to make connections between the murders. Fearing that he may be captured soon, he headed north and began killing in the San Francisco area. He returned to Los Angeles a short time later, though, and made several mistakes that eventually got him caught, including leaving his fingerprint in a stolen car that he was seen driving and allowing a female victim to live, instructing her to “tell them the Night Stalker was here.” The woman had gotten a good look at him and was able to provide a description to the police for a sketch. The police released the sketch along with the suspect’s name—which they determined from the finger-print, as Ramirez had been arrested numerous times for theft, traffic, and drug crimes—to the news media, which published and broadcast the information far and wide.

Ramirez’s murder spree came to an end when he was recognized in public and an angry mob of residents chased him down in the street. They beat him badly and kept him subdued until the police arrived. Richard Ramirez was eventually convicted of thirteen counts of murder and eleven counts of sexual assault. He was sentenced to death but died in June 2013 from complications of lymphoma at age fifty-three.

Perhaps no other city has been afflicted by more terror-motivated serial killers in recent years than Phoenix, Arizona. In January 2018, officials there announced their prime suspect in the deaths of seven people who were all killed in separate, mostly random attacks during the prior November and December. Authorities said they were able to link those cases using ballistics and other evidence to a December double murder, for which a 35-year-old career criminal—the son of one of the victims—was already being charged. Police say that man, Cleophus Cooksey Jr., is now facing at least eight counts of murder and a host of other charges.

That news came on the heels of the arrest in May 2017 of a suspect in a different series of murders that occurred in Phoenix from August 2015 to July 2016. In that case, dubbed the “Serial Street Shootings,” the killer randomly shot at pedestrians in predominantly Hispanic residential neighborhoods, killing nine people and wounding three others. A 23-year-old man, Aaron Saucedo, has been charged in that case and is awaiting trial. In both recent cases, Phoenix residents were terrified that they or someone they loved could be the next victim, and most altered their behavior significantly in response.

These cases also reminded many Phoenix residents of a nightmarish period ten years earlier, when two other serial killers, acting independently of one another, were on the loose in their city. The cases made national news, and a story in the New York Times included an especially apt description of the sentiments at the time: “For many months now, two serial killers who are thought to be responsible for dozens of murders, rapes, robberies and shootings have frustrated scores of detectives and frightened thousands of residents across a wide swath of central Phoenix and its suburbs” (Giblin 2006). The area remained gripped with fear for more than a year.

One of the serial killers, known as the “Baseline Killer” because many of his earlier crimes were committed along Baseline Road, was active from August 2005 to June 2006. His usual pattern was to abduct women from the street—often in broad daylight—and take them to a secluded location, where he raped some and shot to death others. When police arrested 41-year-old Mark Goudeau for the crimes in September 2006, a total of nine deaths, fifteen sexual assaults, and dozens of other crimes had been attributed to the killer. In October 2011, Goudeau was convicted of all nine murders, as well as many of the other charges. He was given nine death sentences, which the Arizona Supreme Court upheld in June 2016.

The other serial killer, dubbed the “Serial Shooter,” was active from May 2005 to August 2006 and would shoot people from a vehicle, mostly targeting those he thought were homeless, prostitutes, or immigrants. When the shooting ended, eight people had been killed and another nineteen were wounded. As police got close to an arrest, they determined that the murders actually had been committed by two people. Roommates Dale Hausner, thirty-three, and Samuel Dieteman, thirty-one, were arrested in August 2006 and charged with the “Serial Shooter” crimes. Hausner was convicted of six of the eight murders, while Dieteman was convicted of the other two. The pair also were convicted of dozens of other crimes, including attempted murders, conspiracy to commit murder, aggravated assaults, and firearms charges. At trial, Hausner clearly enjoyed the attention he received and the sense of power he felt during the shooting spree, even comparing himself to Charles Manson at one point. In March 2009, Dieteman was sentenced to life in prison without parole and Hausner got the death penalty. The state would never execute him, however, as he was found dead in his prison cell in June 2013 from an apparent suicide.

BBC News. 2017, August 3. Jason Marshall killed man in Italy after “bondage sex murder.” Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-40813798.

Fox, J. A., J. Levin, and E. E. Fridel. 2018. Extreme Killing: Understanding Serial and Mass Murder. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Books.

Giblin, P. 2006, July 18. Two serial killers, acting independently, terrorize Phoenix. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/18/us/18phoenix.html.

Hoffman, K. 1998, August 7. Accused baby killer, 69, compared to Ted Bundy. Associated Press. Retrieved from http://www.southcoasttoday.com/article/19980807/news/308079970.

Hoskinson, J. (Director). 2017, August 16. The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. New York: CBS Television Studios.

Jackman, T., and T. Cole. (1992). Rites of Burial. New York: Pinnacle Books.

Langman, P. 2017. Seung Hui Cho’s “Manifesto” [Uploaded document]. Lang-man Psychological Associates, LLC. Retrieved from https://schoolshooters.info/seung-hui-cho.

Lankford, A. 2016. Fame-seeking rampage shooters: Initial findings and empirical predictions. Aggression and violent behavior, 27, 122–29.

Michaud, S. G., and H. Aynesworth. 2000. The only living witness: The true story of serial sex killer Ted Bundy. Irving, TX: Authorlink Press.

Smith, C. 2006. The BTK murders: Inside the “bind, torture, kill” case that terrified America’s heartland. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Wiest, J. B. 2011. Creating cultural monsters: Serial murder in America. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.