When they think of homicide, most people conjure up an image of an evil or deranged criminal who leaves a bloody trail of human remains. It is true that homicide generally refers to the taking of a human life, but not all instances of homicide are criminal. Non-criminal types, known as justifiable homicides, include killing in self-defense, killing in wartime, and state-sponsored killing via capital punishment. Criminal homicides are separated into degrees that are primarily based on the amount of evident malice and forethought.

Involuntary manslaughter describes a homicide in which the perpetrator lacks malice but behaves in a negligent manner that a reasonable person would know was likely to cause serious bodily injury or death. For example, a drunk driver who causes a fatal accident is often charged with this type of homicide. One degree worse, voluntary manslaughter refers to a perpetrator who kills with malice, but only in a split-second decision and within a situation that a reasonable person would find extremely emotionally or mentally disturbing. For example, a man who suddenly snaps when he arrives home to find his wife in bed with another man, whom he immediately beats to death, may be charged with this crime. Another step worse is second-degree murder, which describes a perpetrator who kills with malice and limited forethought—the person has had time to develop an intention to kill but has not actually planned it out.

Premeditated murder is different. It refers to a perpetrator who kills with malice and plenty of forethought. In its extreme versions, this type of murder is well thought out, prepared over time, and committed after rational consideration of the timing and method of taking a life. Premeditated murder is typically considered a form of first-degree murder, which also includes felony murder and capital murder. (The differences among these terms mostly relate to variations in the language of state laws.)

First-degree murder is the rarest form of homicide, but these killings are frequently premeditated. For example, Alachua County, Florida, which includes Gainesville and the University of Florida, has a murder rate that is similar to the overall U.S. rate. An examination of the Florida Department of Corrections’ inmate population database in May 2018 showed that, out of all the current inmates who had committed their crimes in Alachua County, only about 9 percent were serving time for some form of homicide, with first degree murder accounting for less than half of the convictions. Of those murders, however, most had been planned for one week or longer.

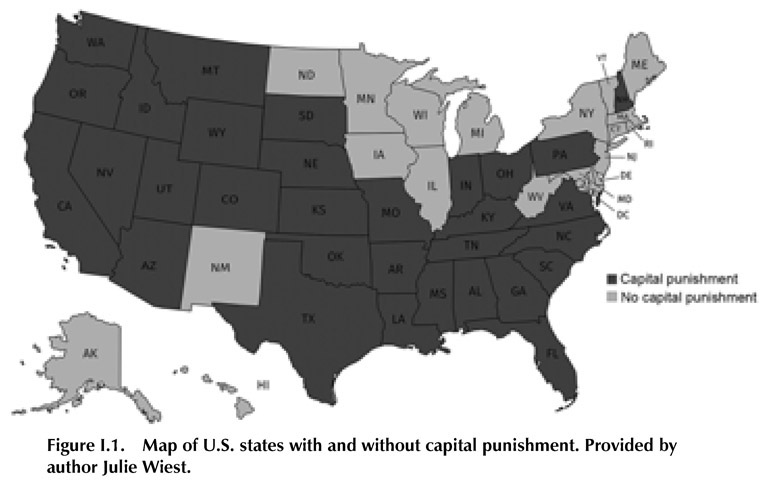

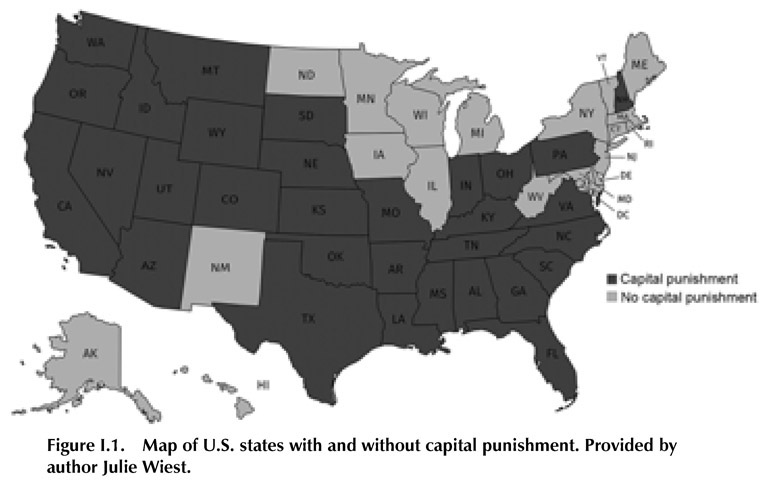

In the event of a conviction, the degree of criminal homicide is substantially related to the subsequent sentence imposed. In most societies, premeditated murder is considered the most hideous and deplorable form of killing someone. Thus, it typically carries the harshest penalties, including life in prison without parole or even the death penalty. Capital punishment is currently legal in thirty-one U.S. states (see Figure I.1), with most of those employing the method of lethal injection. Fifteen of the capital punishment states—Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Kentucky, Missouri, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, Washington, and Wyoming—also maintain secondary methods of execution, available in some cases at the condemned prisoner’s request, including electrocution, lethal gas, hanging, and firing squad.

Roughly a dozen capital punishment states at any given time have in place a temporary or governor-imposed moratorium on its use, often in response to legal challenges in particular cases or because of previously botched executions. When Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf announced such a moratorium in 2015, for example, he said it was “in no way an expression of sympathy for the guilty on death row,” but instead a resolution “based on a flawed system that has been proven to be an endless cycle of court proceedings as well as ineffective, unjust, and expensive” (Berman 2015).

According to Federal Bureau of Investigation (2017) data, there were approximately 17,787 murders in the United States in 2016, which translates to a rate of about 5.46 murders per 100,000 members of the population. That is a slight increase over 2015, but the overall U.S. murder trend has been a steady and collectively substantial decrease over the last twenty-five or so years. Of the 2016 murders, about two-thirds were cleared, meaning a suspect had been identified by the time of reporting. Looking back decades, the clearance rate for murder was over 90 percent in 1965. One possible explanation for the substantial decline in identifying a murder offender now involves the growing number of strangers committing homicide. Arrest is vastly more likely when the relationship between offender and victim is known—when, that is, the killer is a family member, friend, neighbor, co-worker, or classmate—and particularly when that relationship has recently soured.

Any murder causes pain and suffering that ripple through families and communities—of both the victims and the perpetrators—but premeditated murders cause the worst kind of damage. Why an individual would plan, plot, and scheme to kill another person can be difficult to understand. Even though stranger homicides may have increased, many premeditated murders are still committed by people who are known to their victims, often intimate partners, family members, and close friends. In a way, that makes sense, as it generally requires a great deal of emotional investment and energy for a rational person to plot the death of someone else. On the other hand, it can be difficult to understand how someone could take the life of another person with whom they have a close personal relationship, whose humanness and humanity they know first-hand. Other premeditated murders are committed by and against complete strangers. These are even more difficult to understand, as their senselessness and sometimes randomness provide few answers.

Second-degree murder and manslaughter may be despicable, but those acts are also understandable, as they tend to align with common human weaknesses like selfishness, innate impulses, desperation, and emotional outbursts under extreme stress. Most people can relate to someone who impulsively loses their temper and becomes violent in a fit of uncontrolled rage. But the killer who plots over time to take a life—whether for fun, love, money, feelings of grandeur, or no reason at all—that’s more of a mystery.

On occasion, a killer makes plans to take multiple lives. In July 2012, a 24-year-old graduate school dropout shot to death twelve innocent people attending a midnight showing of the latest Batman film at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado. In October 2017, a 64-year-old gunman opened fire on a crowd of 22,000 concert-goers at a country music festival on the Las Vegas Strip, leaving fifty-eight people dead and more than 500 injured. In a January 2018 mass shooting, a 15-year-old student walked into a Benton, Kentucky, high school carrying a semi-automatic handgun, which he used to shoot to death two 15-year-old schoolmates and injure another thirteen. In February 2018, a 19-year-old former student with a history of behavioral problems killed seventeen students and staff and injured another seventeen at a high school in Parkland, Florida. And over a four-day span in the spring of 2018, a 56-year-old Arizona man killed six people, four of whom he associated with his divorce from years earlier.

This book is about the benefits and advantages of those hideous homicides from the perpetrator’s viewpoint. Killers motivated by hate, power, desperation, jealousy, and revenge. Murderers who kill in groups, annihilate entire families, and indiscriminately take the lives of innocent strangers. Sadists who abduct, torture, and literally hunt their victims as if they were animals. The cold, calculated murderers who target loved ones for inheritance and insurance money. And those who kill for seemingly senseless reasons born out of boredom or in search of adventure. It’s about the worst kinds of premeditated homicide in which the perpetrator plans an attack over a period of days, weeks, or months—and leaves behind massive carnage and unspeakable suffering.

In the process of examining the characteristics of premeditated murder, we also address those questions that are commonly asked but usually unanswered, concerning the most enigmatic aspects of this crime. For example, how could a killer have enjoyed his murderous rampage when he committed suicide right afterward? How could anyone in their right mind claim to execute their family members out of love? Why do sadistic killers sometimes regard their murders as great accomplishments? How does premeditated murder provide a sense of power and dominance to its perpetrators? Why don’t gun control measures and background checks for mental illness have a significant influence on the rate of premeditated murders? What can be done to effectively reduce the likelihood of this kind of homicide?

In the 1980s, sociologist Jack Katz (1988) examined the psychological rewards of crime in his seminal work, The Seductions of Crime, which focused on the criminal’s point of view. Decades later, we now investigate the broader range of uses—psychological, sociological, and economic—from the perpetrator’s perspective. Unlike Katz, we take a very broad view of what motivates a killer; we do not examine crime in general but only the worst kinds of murder. Times have changed, but Katz’s thinking about criminal behavior remains embedded in our consciousness.

Examining the killers’ motives for these vicious murders can hopefully lead to better understanding about why they occur. Focusing on the horrendous consequences for victims will do little to explain the causes of such violence. We must explore the range of benefits and advantages—from the viewpoints of the killers—that attract them to commit such brutal acts often with moral impunity. Understanding the allure of premeditated murder is the clearest path toward learning how to prevent its occurrence. Thus, this book explains the common motivations of the most grotesque and hideous kinds of premeditated murder by juxtaposing them with practices of everyday life. In this way, the distance between the inexplicable and the ordinary—indeed, between murderers and the rest of us—is reduced, opening the door for real understanding and the possibility for real solutions.

Berman, M. 2015, February 13. “Pennsylvania’s governor suspends the death penalty.” The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2015/02/13/pennsylvania-suspends-the-death-penalty.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2017. “Crime in the United States, 2016: Murder.” Uniform Crime Reports. Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2016/crime-in-the-u.s.-2016/topic-pages/murder.

Katz, J. 1988. Seductions of crime: A chilling exploration of the criminal mind—from juvenile delinquency to cold-blooded murder. New York: Basic Books.