CHAPTER TEN

THE OLD BEXAR COUNTY JAIL

On the cross streets of Commerce and Camaron lies a building that most people believe to be very haunted. The bars on the front windows and the old-style architecture whisper of another time when this building played an important part in San Antonito’s history.

In 1878, the City of San Antonio was in desperate need of a new jail to house its ever-growing population of prisoners. Alfred Giles was hired to be the architect, and he designed a two-story limestone building that held twenty cages for its occupants. Due to the location of the new jail, it was soon nicknamed “the Shrimp Hotel” (camarón is Spanish for “shrimp”). One year later, the jail was completed and ready to check in its very first “guests.”

Throughout the jail’s history, expansion for the building was continually necessary. After a few decades went by, San Antonio’s population had grown enormously, and with that growth had come the need for a larger jail. So in 1911, Henry T. Phelps was commissioned to build a third floor to the Bexar County jail, and in 1912, it was finished.

As he designed and built the third level, very original attributes were added inside that were not normally found in a jail of this time. For instance, the gallows were built inside the building, instead of outside, as was the custom.

The Holiday Inn Express and former Bexar County jail.

In those days, hangings were normally seen as a social event. Businesses would close, children were let out from school and the whole town would gather to watch. However, in the current design of Phelps, that form of amusement was left out. The gallows were redesigned to be on the third floor of the building, for a more private viewing. Only a select group of individuals (family, jury, etc.) would be permitted to watch.

With the new design, the prisoners were led up to the third floor and placed over a trap door. While on the trap door, a hood was placed over their heads and the noose around their necks. The lever would then be pulled, and the unfortunate soul would drop to the second level, where an audience of one hundred or more watched on. Also watching the hangings were the prisoners whose jail cells lined the area, perhaps to see the consequences of their actions.

In 1926, expansion was once again needed, and Atlee and Robert Ayres, a father-and-son duo, added on an additional two floors for a grand total of five floors. Also designed was the arched entrance porch that we see today.

The Bexar County jail shares much history as a building, but within its walls, the jail contains tragic stories of prisoners, riots and many hauntings. But there is one person and one event that stand out among the rest. This is the story of the last public hanging in San Antonio.

There is a popular phrase uttered by the aging generation in San Antonio: “la chansa de Apolinar.” What does it mean? It can be translated to mean “the luck of Apolinar.” Although that doesn’t seem to make much sense to most, in Texas—most commonly, in San Antonio—it does. We know it to mean, “Not a chance in hell.” The phrase was coined after Clemente Apolinar became the last person to be hanged inside the old Bexar County jail. The phrase came about due to people believing that Clemente should have been freed and had no chance of winning in court, or escaping the gallows. Some call the hanging an act of injustice, but on the other hand, some might believe he got what was coming to him. We will let you decide.

It was a hot summer day, August 16, 1921, when Clemente, a young Mexican American, was taking a route from a relative’s home in Floresville, Texas, to San Antonio. (Driving today, the journey is long, but on foot, his travel could have taken more than twelve hours.) The summer was hotter than usual, and he became very thirsty. Luckily, he knew the area quite well and had made this trip several times throughout his twenty-nine years of existence; he even had a favorite spot to rest where he could fetch some water to drink.

He came to a small spring that branched from the Salado Creek. (Today, we know this area to be where Interstate 10 crosses with Roland Avenue.) During those days, the creeks and rivers were filled to the brim and springs were plentiful. Where he stopped was his own personal oasis. He knew this spring to have the freshest and best tasting of all water in the area.

As Apolinar approached the bank, he kneeled down and quickly realized that the water appeared to be extremely muddy. Of course, he could not drink such filthy water and left the bank extremely angered, wanting someone to blame. He felt that someone got there before him and maliciously stirred up the riverbed, making the water undrinkable. So, swiftly Clemente went up stream to find that person and show him a lesson.

Not too far up, Theodore (fourteen years old) and Kirby (twelve years old) Bernhard, brothers, decided to take a rest as well. In the hilly East Side pasture near the old Bem Brick Yard, the boys were herding cattle and went down to the water to play. They were racing their little toy boats down the current, when out of nowhere Clemente appeared.

In Clemente’s hands, he held a large rock. Screaming and yelling at the boys, he chased them away from his water. Of course, Clemente felt that those two young boys were the culprits, and he was out to get even. After a small chase, Clemente caught up with Theodore. He took the large rock he was holding and smashed it over the young boy’s head. Over and over again, he smashed the boy’s skull, cracking his cranium until the boy was dead.

But Clemente was far from finished. Still going through the emotions of his vengeful rage, he began to savagely mutilate the body. He took out his knife and cut the boy ear to ear, down the bridge of his nose and around to the back of the neck, even cutting open the top and back of his cranium. He continued by opening up the boy’s head. With the lifeless corpse on its belly, Clemente began to remove the boy’s brain, scooping it out and smashing it on his back till it was mush, leaving it there and even putting some in the boy’s back pockets. He then filled the empty cranium with random debris he found near the bank: mud, sticks and small rocks.

Still, not completely done, he closed the boy’s head and turned the body over. Straddling the corpse, he cut off the ears, all while laughing maniacally. He decided that his revenge was not yet complete, however. He wanted to take a souvenir with him. So Clemente, with his bare hands, went to the boy’s head, burrowed his thumbs deep into the eye socket and gouged out one of the eyes, which he stuck in his vest’s breast pocket. This final act left Clemente completely satisfied.

While the murder was taking place, Kirby (the younger brother) was off to find help. Running from the attack, he went to a nearby road and stopped the first people he found, two old men driving their buggy. Kirby came out screaming, “A Mexican is down in the brush after my brother with rocks!” and “I want you to go down there and make him stop!” A.G. and L.P. Holmes, also brothers, were quickly led to the scene. One later testified, “He was mutilated as bad as anything I ever saw in the world. I never seen anything like it. I don’t want to see any more like it. His skull was broke all behind, plumb open on both sides.” There, still at the scene, was Apolinar, all covered in blood. He stood up, pulling back the bloody rock, and yelled for those men to leave. So they did.

While the Holmes brothers were down by the creek, Kirby was off searching for more reinforcements. Clemente was way too much for any two men to handle alone. He stopped a brick delivery truck in which an African American, Elijah Johnson, was driving. By this time, Kirby knew that his brother was already dead, so he shouted out to Johnson, “Oh, will you please stop. A Mexican has killed my brother!” Johnson jumped out of the truck, grabbing his sitting board—a piece of one-by-six-foot wood—and rushed down to the water. Kirby warned, “He’ll kill you!”

Johnson shouted back, “Oh, I’m not afraid of him.” At that time, Clemente was about to take off. Johnson came to the murder scene and saw him whistling and singing in the most lunatic way. By this behavior, Johnson was convinced he should go get his shotgun. By the time he returned, Clemente had vanished from the scene.

After leaving the scene of his gory deed, Clemente came to familiar homes and faces in the street. Bragging about killing the little white boy and still covered in blood with the same bloody rock he crushed the boy’s head with in hand, Clemente went up to people showing off his souvenir. Pulling out the boy’s eye from his vest pocket and holding it in his other hand, he forced people to stare at it. He bragged about the murder of the boy and said disgusting phrases referring to the eye: “Don’t it look like the eye of a dog?” or “Don’t it look like a little marble?” From person to person, he went through the area; he was very proud of what he had done.

Soon after, the police caught up with him; he was easily found, being covered in blood and raging. He told the arresting officer, “I’m crazy. The law can’t touch me.” They threw him into the old Bexar County jail, where he was to await his trial.

Indeed, Clemente was crazy, and all who met him instantly knew that. Early in life, he was seen as different. Developing slower than children of his own age, he identified himself with children years younger than he was. Often picked on, he fought with other children. Once, he was caught in a rock fight and took a violent blow to the head. Never treated, physicians believed his brain’s temporal lobe was damaged. Unknown in those days, the symptoms he had would have included seizures, violent rages, paranoia, lack of facial expression, schizophrenia and hallucinations. He was never the same after that. Throughout his life, he was committed to the South Western Insane Asylum located in Southeast San Antonio three times being found insane: 1907, 1909 and 1916. Whenever committed, he would always find a way to escape and often got into more trouble.

The trial began, and of course, he was found guilty. He never denied what he had done but, in fact, bragged about killing the little boy. The murder of young Theodore is considered to this day San Antonio’s most brutal murder.

At this time what would be done with Clemente was unknown. Most heard the sorrowful cries of a mother, “Won’t they do something to that man who took my boy from me?” Sides were taken, and the city became divided. One half of the city, the Mexican American population, wanted life for the insane and misunderstood man, while the other half of the city wanted Clemente, a symbol of evil, to be put to death for the brutal crime he committed. It was up in the air for the court to decide his mental consciousness and his fate.

Testimonies where made during a nine-day insanity hearing. Thousands of people swarmed the courthouse to hear what would be done, some to give support to Clemente. During the hearings, Clemente’s character was on the line. One physician declared that Clemente had a “mania to kill.” Most believed he would kill again. His brother and mother said a few words, stating he was not sane; he was haunted by ghosts and suffered hallucinations. But what caught the jury was the damning statement by Clemente as he explained that “I would have killed the other boy too if he wouldn’t have gotten away!”

Maybe no one knew what to do with him other than put Clemente out of his misery. But the all-white male jury found Clemente legally sane. They believed he knew and could distinguish the differences between right and wrong and should pay the price. The sentencing came immediately afterward. Clemente Apolinar would suffer the consequences of his actions and would hang until he was dead.

Many praised the judicial systems of Bexar County because justice would be served. But for many, the judicial system had failed Clemente. Those who believed that did not want the death penalty for Clemente but wanted him institutionalized for life. Petitions for a retrial made their ways to the governor of the state. Riots even took place in the streets, but still, nothing could change Clemente’s fate.

Almost two years went by, and finally, in 1923, Clemente sat in his jail cell of the old Bexar County jail awaiting his execution. For him and his family, February 23 came a little too soon. On the day of his hanging, Clemente was refused his final rites by the Catholic Church; he ate his final meal and said his goodbyes to his family. By 11:00 a.m., all was ready for his execution. Sheriff John W. Tobin had the family leave as he read Clemente his death warrant. Then, the prisoner was escorted to the gallows.

As he walked to the gallows, hands tied behind his back and shackles around his feet, the other prisoners sang familiar tunes to ease his heart, “Lord I’m Coming Home to Sin No More” and “Nearer My God to Thee.”

On the third floor, all awaited the moment Clemente would fall through to his death. That day, crowds of people came from all over. An estimated five thousand people gathered around the jail just to hear the slam of the trap door as he fell through. Some climbed buildings and trees just to get a glimpse of the lifeless body. This was a day most waited for.

As Clemente was placed over the trap door, the executioner gave him the option all prisoners were allowed: to wear the black hood or not. On record, Clemente was the only prisoner to reject wearing it. The noose was then placed around his neck.

At 11:07 a.m., he faced the crowd and said his final words: “Adios. My Jesus, mercy; Mary, my mother, help me.”

The lever was pulled, the trap door slammed open and Clemente disappeared from the third floor’s view. The audience became hushed as it watched him fall through to the second level.

Most were horrified when his body came into view. Something horrible had happened that had never been seen before. The force of gravity had snapped his neck and the rope tightened, crushing the larynx—death was almost certainly instant. But what happened during that instant would be remembered forever. The rope severed the neck, almost decapitating the head from the body. The jugular vein and the carotid artery were sliced and people up to eight feet into the audience became covered in Clemente’s blood. People screamed and ran for the doors. This was not supposed to happen.

News of Clemente’s hanging spread like wildfire throughout the city, and people from all over South Texas could not stop talking about Clemente Apolinar and the awful fate he suffered.

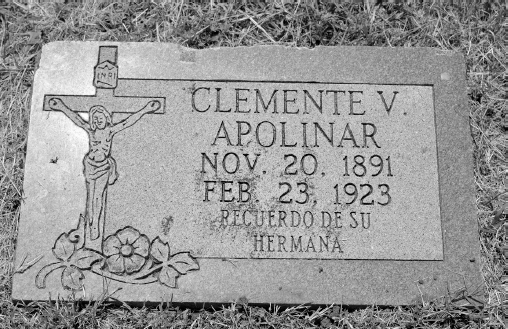

Tombstone of Clemente Apolinar located in San Fernando Cemetery 1.

During his funeral service, more than eight thousand people filed by to see Apolinar’s body. He was buried the Sunday after the hanging in the San Fernando Cemetery 1, where just as many came by to show their respects. There at his grave, flowers were piled waist high for weeks.

Whether you believe justice was served or not, Clemente became a legend. Known for viciously murdering that little boy and for what some believed to be an unfair trial of the mentally insane, his story will remain known forever here.

Because of what had happened to Clemente, hangings were seen as inhumane and soon were abolished. However, not much later, the electric chair was invented and introduced inside the jail as a more “humane and effective way of execution.”

In 1962, due to overcrowding, the original Bexar County jail closed. The city had grown so rapidly over the near century of the jail’s existence that the building was found to be obsolete, and a new jail was built. However, the building did not remain dormant. It was bought and used as a county polling site for years until 1983, when the Bexar County jail started using the building as an archival storage facility.

Years passed by, and our once famous jail began to be overlooked and unnoticed. Thoughts, stories and memories of the old Bexar County jail began to dissipate.

In 2002, the building was restored to life. The Comfort Inn Hotel chain was looking for a new building to place a hotel close to the River Walk. It was directed to the old jail and decided its location would be perfect. Comfort Inn purchased the building for over $800,000 and soon began preparations to completely change it. However, the San Antonio Conservation Society reminded the hotel chain that this was an historic building. Therefore, the company could not change the exterior, only the interior. So the original bars and outside façade still look very much the same as they did so many years ago. Today, it is a Holiday Inn Express and attracts thousands of visitors a year. Very few of these guests know the history and events that once took place inside of this hotel.

Ghost sightings and unexplainable experiences seem to haunt the hotel today. Guests often complain about their rooms being extremely cold, even during the summer heat. Some have tried turning on the heater in an effort to warm the room, but it doesn’t seem to help. Other guests are scared to come back to their rooms because their windows have been opened and lights turned on while they were away. This is strange, for the windows are very old and original to when it was a jail. There are signs posted everywhere stating not to open them because of their age.

Recently a mother and son stayed at the hotel, and they related to us an experience they had while they were there. They had come back from a long day of sightseeing and were exhausted. They went up to their room and found that everything had been cleaned while they were away—everything, that is, except for the bed. She thought it was strange that the staff had forgotten to make it. As she was looking closely, she suddenly noticed an indenture in the bed, as if a person were on it. She reached out her hand to touch the place, and suddenly, the indenture disappeared. As if someone or something had just gotten off the bed. She also noticed that when she had touched the bed, she felt body heat, as if someone was just sleeping there. Scared by this experience, they asked to change rooms.

People who stay at the original jail have complained to the front desk in the morning about hearing whispering and voices in their rooms. When they awake and turn on the lights, the voices disappear. Some have even awoken to the sound of men singing in their ears.

The breakfast area in the lobby sometimes has to be placed back together. During the night, furniture and chairs are rearranged, flipped over and placed in odd spots. We were told by the front desk that the original noose that hanged Clemente was once hanging from the lobby wall. Some people were offended by this, and they had to take it down. Today, it hangs inside a local sheriffs’ office.

One night, when a security guard was on duty in the lobby, he said a young man came running down the stairs carrying his luggage and only wearing his boxer shorts. He looked terrified, and it took him a while to speak. When he did, he said we wanted to leave the hotel. He said while he was working late on his laptop computer, it was suddenly lifted out of his hands and thrown violently against the wall. He sensed a dark presence in the room and grabbed his stuff before he took off running. He checked out of the hotel and vowed he would never come back again.

So the next time you are in San Antonio and looking for a place to stay on a budget, you know where to choose, the Holiday Inn Express, our former Bexar County jail.