Left to his own devices he couldn’t build a toaster. He could just about make a sandwich and that was it.

—Douglas Adams, Mostly Harmless (1992)

For Merle, Bette,Vito & Felix

Published by

Princeton Architectural Press

37 East 7th Street, New York, NY 10003

For a free catalog of books call 1-800-722-6657

Visit our website at www.papress.com

© 2011 Thomas Thwaites

All rights reserved

14 13 12 11 4 3 2 1 First edition

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Editor: Sara Bader

Designer print edition: Paul Wagner

Special thanks to: Bree Anne Apperley, Nicola Bednarek Brower, Janet Behning, Fannie Bushin, Megan Carey, Becca Casbon, Carina Cha, Tom Cho, Penny (Yuen Pik) Chu, Russell Fernandez, Jan Haux, Linda Lee, John Myers, Katharine Myers, Margaret Rogalski, Dan Simon, Andrew Stepanian, Jennifer Thompson, Joseph Weston, and Deb Wood of Princeton Architectural Press

—Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Thwaites, Thomas, 1980–

The toaster project, or A heroic attempt to build a simple electric

appliance from scratch / Thomas Thwaites. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-56898-997-6 (alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-61689-119-0 (digital)

1. Thwaites, Thomas, 1980—Themes, motives. 2. Manufactures—Miscellanea. I. Title. II. Title: Heroic attempt to build a simple electric appliance from scratch.

NK1447.6.T49A35 2011

683'.83—dc22

2011006094

Where do the products that fill our lives come from? “China” is, of course, the standard answer to this question. The “dragon economy’s” mammoth factories are high in our consciousness, drawing the attention of environmentalists worried about the effects of breakneck industrialisation and Western politicians troubled about competition.

But “China” is an inadequate answer. Where do our things really come from? What lies behind the smooth buttons on your mobile phone or the elegant running shoes on your feet? What is involved in extracting and processing the materials that give themselves up from the earth so reluctantly? Where does the copper in your “Made in China” kettle come from? Were the electronic components and integrated circuits in your TV remote control assembled by machine or by hand? And what exactly has been integrated in that circuit anyway?

We rarely ask these kinds of questions. Perhaps the nature of our consumer culture makes us averse to them. Consumer goods play a clever game of “hide and show” with us: they call our attention, promising to satisfy our wants. Yet, at the same time, they veil their origins. Appearing to have no history or past, they materialise on the shelves of our shops as if by magic. This is what Walter Benjamin described as the “phantasmagoria” of commodity culture. Modern societies, it seems, not only forget the material and practical origins of the commodities they consume, they seem to have elevated them to minor deities.

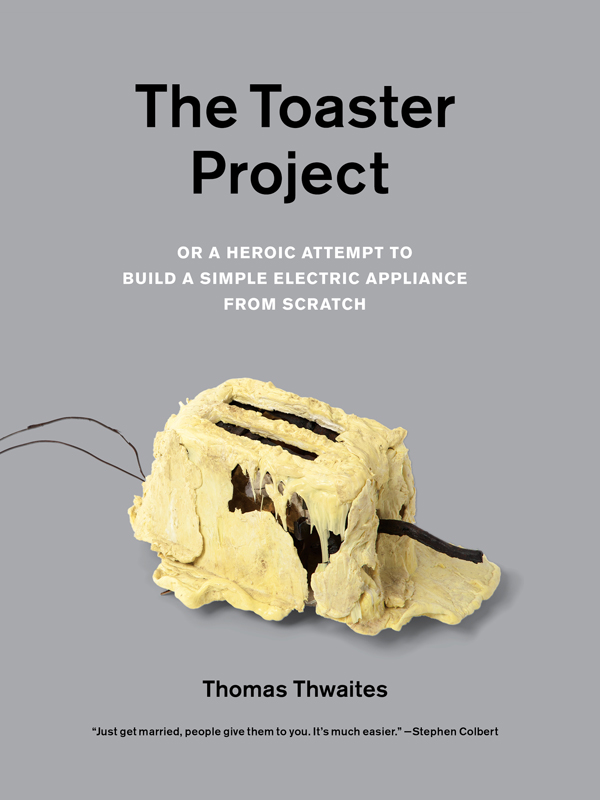

In The Toaster Project Thomas Thwaites set himself the task of making one of the most commonplace consumer goods from scratch. This meant not assembling this modest appliance from other existing components but extracting and processing the materials from which the parts of a toaster are made. This book records his major failures and minor triumphs.

Thwaites begins his mission by dismantling the cheapest toaster on sale in the shops. This is an exercise in reverse engineering, the dark art practiced by military engineers trying to learn enemy secrets and copyright lawyers attempting to track down patent infringements. Thwaites’s project rapidly becomes another kind of reverse engineering. Acting alone and eschewing the armoury of techniques available to modern industry, he finds himself in the position of late-medieval man with a limited repertoire of skills and expertise. His most effective guide to the task of smelting iron from ore is, for instance, not the latest issue of International Journal of Material Sciences but De re metallica, a sixteenth-century treatise.

Modern myths of omnipotence come to seem like hubris when Thwaites is defeated by the task of smelting metals, something first practiced eight thousand years ago. We know more now, don’t we? We are more expert than our ancestors, aren’t we? Yet, at the same time, we are also reliant on the knowledge they produced. This is pointed out by the philosopher Michel Serres, in Conversations on Science, Culture, and Time (1995), when he asks us to consider a new car:

Submerged in our toasters are layers of hard-won and deeply practical knowledge—if only we could tap it.

In the spirit of many recent endeavours to limit the techno euphoria of twenty-first-century modernity, Thwaites set some sharp restrictions on his project. Famously, Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg called for filmmakers to return to first principles in their “Vow of Chastity.” The obligation to shoot on-site with actors, using natural sound and handheld cameras, would, they argued, ensure a cinematic purity that has been lost in the age of CGI (computer-generated imagery) and lowbrow cinema. Thwaites’s particular holy “vows” seem simple—“I must make all the parts of my toaster from scratch” and “I must make my toaster myself”—but like most rules, they require interpretation. Making a toaster “on his own” means not employing other people, but in the world today, can anyone ever really be entirely independent, forgoing the expertise and services of others? Surely that’s the lonely territory of antimodern hermits like Theodore Kaczynski, author of another vow of chastity, “The Unabomber Manifesto.” The Toaster Project—over time—becomes a social one: in the course of his quest, Thwaites makes willing conscripts of professors, press officers, and even amiable drunks.

In one regard, Thwaites’s Toaster Project seems closer in spirit to von Trier’s Five Obstructions (2003) than the “Vow of Chastity.” In this documentary the Danish filmmaker set his friend and mentor, Jørgen Leth, the task of filmmaking under five impossible conditions. Failure was guaranteed, but what made the project worthwhile was Leth’s resourcefulness and imagination (as well as his attempts to stretch the rules). Making a toaster from scratch is surely an impossible task, but not a pointless one. Thwaites’s project reveals much about the organisation of the modern world, not least the extent to which Britain’s industrial capacity has been dismantled. The country’s mines, foundries, and factories have become, it seems, another form of phantasmagoria.

Hello, my name is Thomas Thwaites, and I have made a toaster.

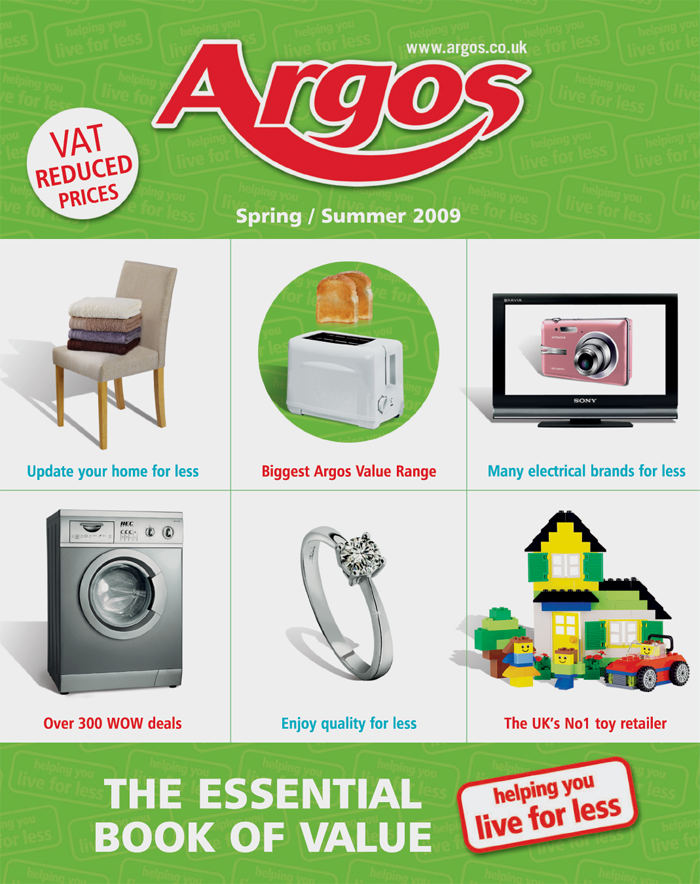

It took nine months, involved travelling nineteen hundred miles to some of the most remote places in the United Kingdom, and cost me £1187.54 ($1837.36). This is clearly rather a lot of time, effort, and money expended for just an electric toaster, but when I say, “I have made a toaster,” I mean really made it, literally from the ground up; starting by digging up the raw materials and ending with an object that Argos sells for only £3.94 ($6.10).

Argos Spring/Summer 2009 catalog

Actually, this is just a version of the truth. An alternative version would be that I tried and failed to make a toaster. That’s not to say I haven’t got a rather odd-looking appliance that kind of toasts bread sitting on my kitchen worktop, which cost £1187.54 and caused me to travel around the United Kingdom for nine months. No, what I mean is that although I set out to make my toaster completely from scratch, I realised along the way that there can be no such thing as “from scratch.”

As I sit writing this in a café in London, everything I can see, except maybe some woolen clothes and some wooden furniture, began life as a collection of rocks and sludge, buried in different parts of the world. It’s not that this café has a geological theme or something, it’s that the rocks and sludge have been transformed in some extremely clever ways, becoming this laptop, or the tasteful wood-effect plastic flooring, or that electric toaster.

How the hell do some rocks become a toaster?

This fundamental question motivated my, let’s face it, faintly ridiculous quest to make one from scratch. But I also wanted to explore the grand-scale processes hidden behind the smooth plastic casings of mundane everyday objects, and to connect these things with the ground they’re made from. I’m interested in the economies of scale in modern industry, the incremental progression of science and technology, and exploring the ever-widening gulf between general knowledge and the specialisms that make the modern world possible. The point at which it stopped being possible for us to make the things that surround us is long past. Well, that’s what it feels like, but is it?

My toaster took me on a journey not only around the United Kingdom, but on a trip through civilisation’s history as well, from the Bronze Age to today.

The following pages are the story of that journey, and that toaster.