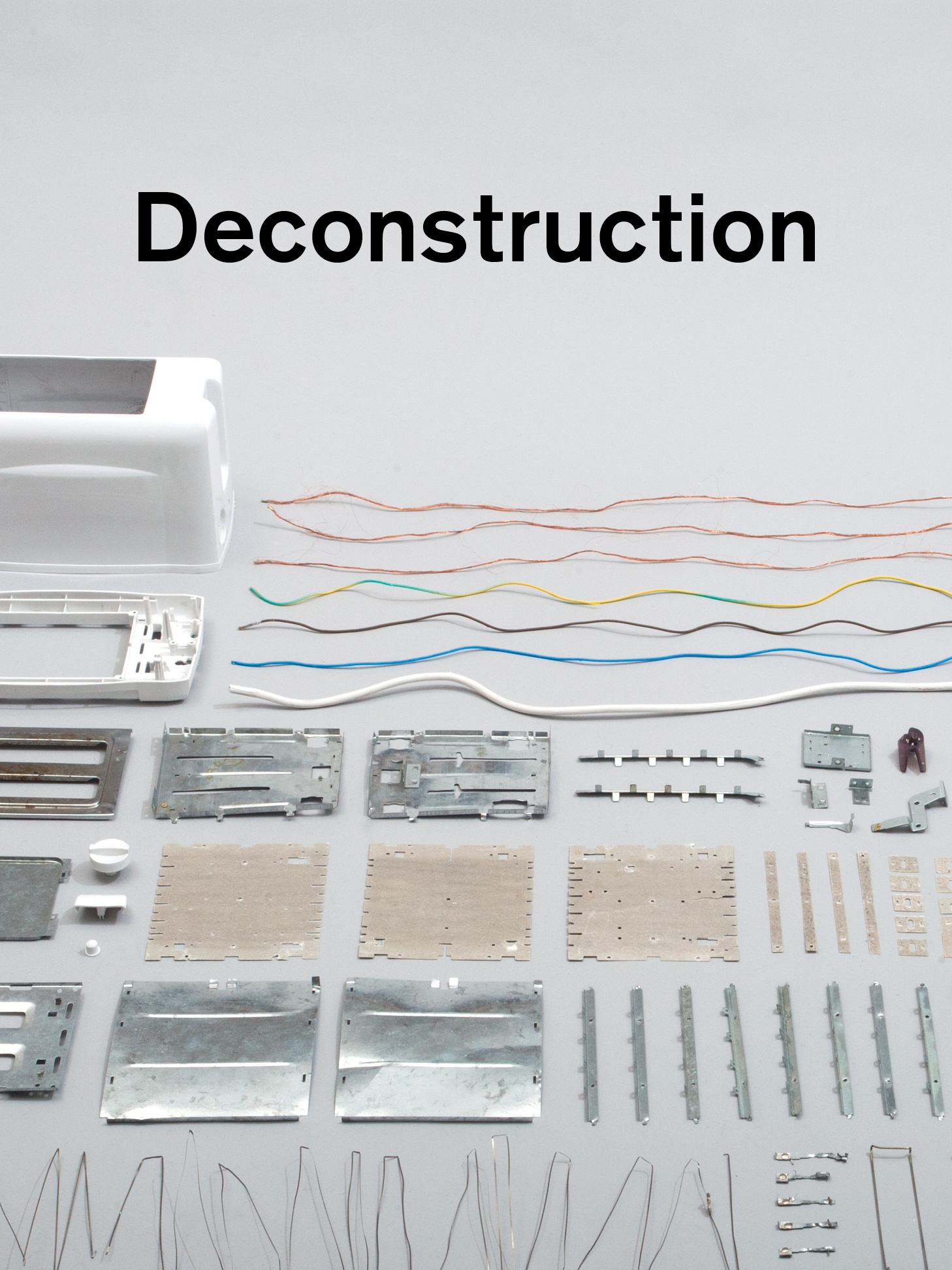

Deconstruction

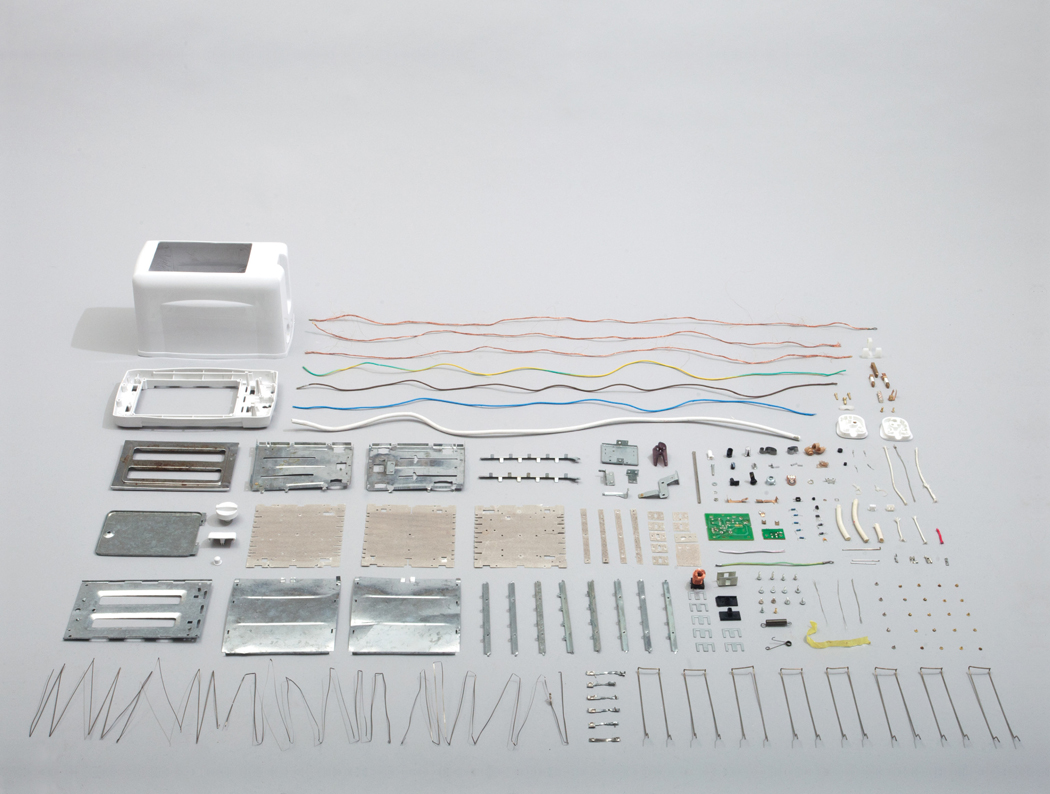

Reverse engineering is the process of deducing how something works by taking it apart. Using the potentially misguided rationale that the cheaper the toaster the fewer parts it will contain, and thus the simpler it will be to reproduce, I dismantle the cheapest toaster I can find: the Argos Value Range 2-Slice White Toaster.

So, let’s see what you get for your £3.94†...

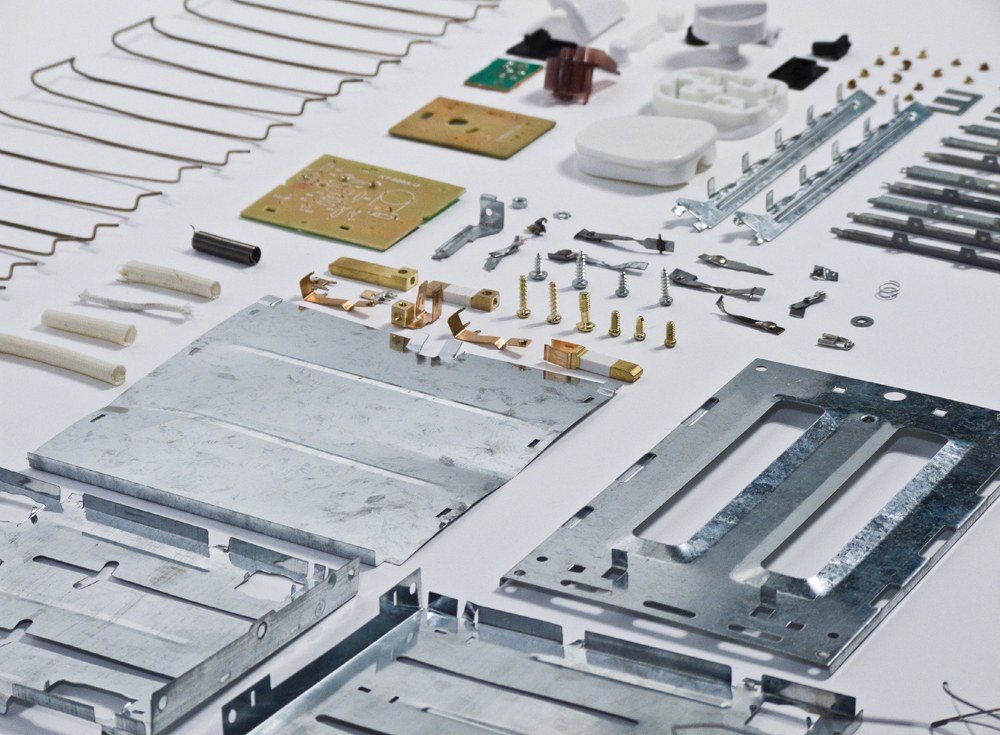

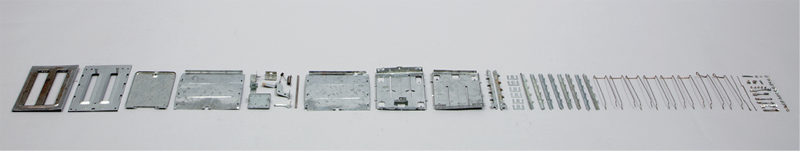

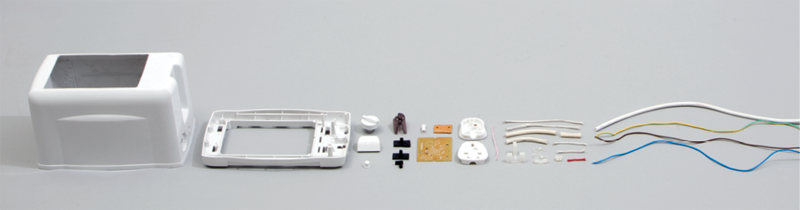

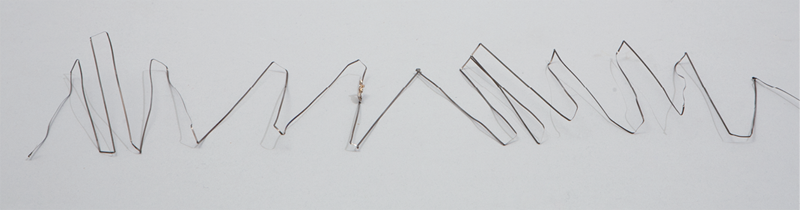

I dissect my patient into 157 separate parts, but these parts are made up of sub-parts, which are themselves made up of sub-sub-parts. Does the variable resistor that controls the toasting time count as a single part? But it’s made of eight sub-parts, so perhaps it should count as eight? Does a capacitor count as one part or eight? I peel open its thin outer plastic covering, open the inner metal casing, and rolled up inside are two very thin strips of metal with a metal pin clamped to each, with a strip of weirdly damp paper (soaked in some chemical perhaps?), and a rubbery bung through which the pins poke to be soldered onto the circuit board. And what about the live, neutral, and ground wires of the power cord, coated with colourful plastic and all contained within a white plastic outer sheath? What about the forty-two individual strands of copper, woven together to make up each of the live, neutral, and ground wires in the power cord? If I were to dissect all the components all the way down to their discrete “bits,” then I’ve calculated my toaster-part count would be 404 individual bits.

What’s inside . . . a capacitor?

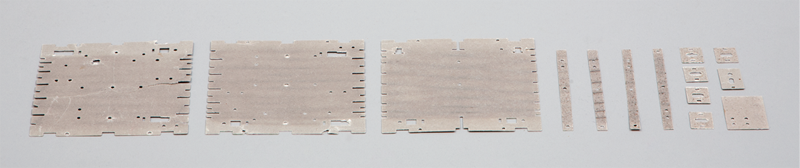

Things get even more difficult when you start trying to divide the bits according to their material. First, without some serious chemical analysis, it can be impossible to tell if two plastic parts are the same plastic, or in fact different plastics that just look the same. Ditto for the metals.

On top of that practical constraint is the more metaphysical question of what is “the same”? Presumably the brown, blue, and green and yellow striped insulating sheaths of the wires are the same plastic, but they must have different pigments added to colour them. Does this then make them strictly different materials?

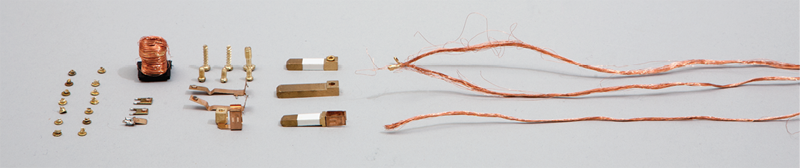

The metals, which I thought would be fairly easy to identify, also pose problems. I can pick out the copper OK (though even then some bits of copper appear more “copper” coloured than others), and the bits that are brass coloured are presumably made of brass.

Except that the brass-coloured screws are magnetic, whereas the brass-coloured pins of the plug are not. Steel I know is definitely magnetic. But while some of the silvery metal parts are magnetic and so could be steel, many are not. Depending on where in the toaster they’re found, two very similar-looking metals can have different properties, or parts that you’d expect to be made from the same material (like the two springs) are clearly not (they’re different colours, for a start).

The materials used in the electronic components are a whole other story. What’s the metal inside a transistor? What’s that white stuff inside the resistor? The six-coloured bands meticulously painted on every single resistor to show how much they resist the flow of electrons: what are the paints made of? Where do the pigments come from?

If I lump stuff together that roughly looks like steel, that looks like brass, that looks like copper, and so forth, without worrying too much about “slight” differences in colour or consistency, and put plastics together that feel the same, and don’t get too lost in all the different exotic materials in the electronics, then I estimate that my toaster is made of at least thirty-eight different materials. Seventeen of these are metal, eighteen are plastic, two are minerals (the mica sheet and talcum powder stuff inside the power cord), and one is just weird (strange wet papery rubber inside the capacitor).

If I got some kind of chemical analyst involved, then the materials count could easily rise to over a hundred.

Bugger.

I’d expected a toaster to be perhaps a little complex, but really, four-hundred-plus parts? One-hundred-plus different materials from God knows where? How could something with this much in it cost £3.94, the price of a hunk of cheese, and not fancy cheese either.

Steel

Mica

Plastic

Copper

Nickel

My life’s work stretches out in front of me... It wouldn’t be so bad, travelling the earth on a quest to extract the hundred materials I need to create my vision, searching for semiconductors amongst icy glaciers, exotic forests, and forgotten lakes. I could grow a beard. After a few years I might tell my story to a fellow traveller and become something of a legend. Eventually someone might start a Facebook group about me, “Fans of the mad bearded Englishman wandering around India trying to make a toaster.”

Hmm.

Alternatively, I could make a few minor material substitutions.

To start with, the element: the hot passion within every toaster. No element = no heat = no toast. After some research I discover that for most toasters, the element is made of nickel-chromium resistance wire, sold under the brand name Nichrome. Nichrome is used because it has a high electrical resistance, so it gets hot when an electric current is passed through it, but it’s also got a high melting point, so it doesn’t melt when it gets hot.

Unfortunately, after a little more research I find that to extract chromium from its ore, one produces a by-product called hexavalent chromium. If you’ve not seen the film Erin Brockovich, next time it happens to be on TV, have a look. It’s based on a true story, and it’s got Julia Roberts in it. She plays the peppy legal clerk who takes on the giant Pacific Gas and Electric Company, acting on behalf of some people suffering from a debilitating sickness caused by the hexavalent chromium used in the PG&E plant. If Julia Roberts says the stuff is bad, I think I should avoid it if I can.

Fortunately for my health, heating elements can also be made from Constantan, an alloy of copper and nickel consisting of about 55 percent copper and 45 percent nickel. I can replace the dangerous chromium with copper, which I need for the wires anyway, and kill two birds with one stone.

Brass, which I’d need for the plug pins, is just copper with a touch of zinc. Zinc sounds rather exotic. I don’t see much advantage to it, to be honest. I’ll lose the zinc and just use plain old copper. And so on... I pare down my materials to the bare minimum from which I think I can make a toaster that retains the essence of “toasterness.” These are: steel, mica, plastic, copper, and nickel.

I’ll travel to a mine where iron ore is found, collect some ore, somehow extract the iron myself, and then somehow change it into steel. The same for the mica, copper, and nickel. I’ll need to get hold of some crude oil from which to refine the molecules for the plastic case.

I’m going to need some advice...

† Price correct at time of writing. There must’ve been some kind of major upheaval in the value toaster manufacturing business, because since then the price has rocketed to £4.47 ($6.95).

Thomas

From: Cilliers, Jan J l R <j.j.cilliers@imperial.ac.uk>

To: thomas@thomasthwaites.com

Date: 7 November 2008 07:16

Subject: Re: The Toaster Project?

Thomas,

This is utterly fabulous! Come see me whenever you can, I would be happy to help in whatever way I can.

Call me on 07 ———— first, or email.

Jan

The Royal School of Mines, Imperial College of Science and Technology, London

Professor Jan Cilliers, Chair in Mineral Processing and director of the Rio Tinto Centre for Advanced Mineral Recovery

The Royal School of Mines, Imperial College, London

Senior Common Room

Friday, 7 November 2008 (Lunchtime)

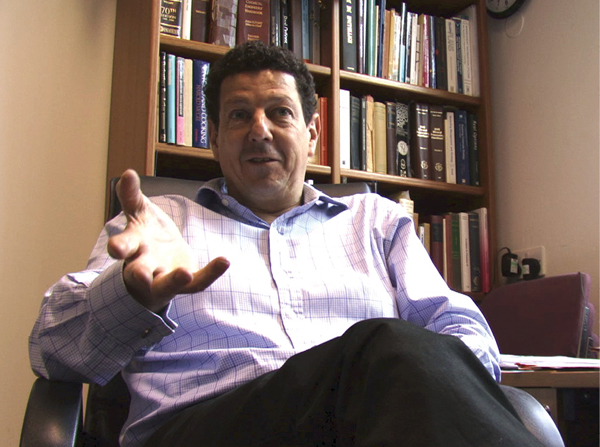

Professor Jan Cilliers holds the Chair in Mineral Processing at the Royal School of Mines at Imperial College and is the director of the Rio Tinto Centre for Advanced Mineral Recovery. He’s also a jolly nice chap; he bought me fish and chips at the Imperial College Senior Common Room. The following is a transcript of our conversation. For succinctness I’ve removed about a half hours’ worth of me saying “err,” “um,” “well,” and “you see.”

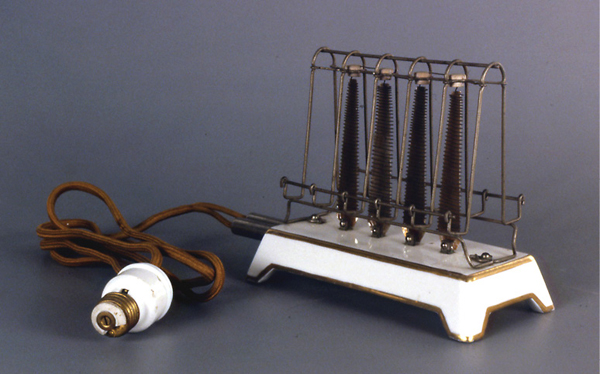

PROFESSOR CILLIERS: So, this toaster thing. In toaster terms I have lived through several generations of toasters. The first toaster we had in my house had little doors that opened up — and when you opened the door the bread turned itself. Do you remember those?

ME: Um, not really, no.

The reason I ask is that one of these toasters would be much simpler to do than a modern toaster. I assume it’s not going to pop up, right?

I would quite like to try and make it pop up.

Bloody hell.

I was even thinking, well at some point somebody made the first transistor or resistor or capacitor or something, so it must be possible to make these things yourself.

You’re going to plug it in and you want it to work? So are you going to make the cable or...?

[I nod my head.]

Really. Right, well. How much time have you got?

Until the degree show next summer.

I see. So, why a toaster?

Well, I guess because they break all the time. [This was not a brilliant answer. I knew it, and Professor Cilliers clearly expected more of an answer to a question quite fundamental to the project. At a loss, I played the artist card...] And well, you know, a toaster just feels right.

[Oh dear. A toaster “feels” right.]

SO, WHY A TOASTER?

What I didn’t say to Professor Cilliers at the time but have since discovered is something along the lines of the following. The reason that I want to create a toaster, specifically an electric toaster, is because the electric toaster, like no other object, seems to me to encapsulate something of the essence of the modern age. To understand how they achieved this status, we’ll have to look back at how they came to be such a mainstay of kitchen life for the peoples of the world who toast.

Toast: A Brief History

The first toaster, of course, is a bit of a grey area—probably being nothing more than a stick with a piece of bread on the end of it held over a fire. In ancient Rome toasting was a popular way of preserving bread; tostum is Latin for burning. Fact.

Toasting really took off, however, with the invention of the electric toaster at the beginning of the 1900s. The years before had seen electricity begin to change people’s way of life. The Edison General Electric Company established the first central power station in New York in 1882 to power the eight hundred electric bulbs of its subscribers. The same year the first power station in London (near Holborn viaduct) was switched on, providing electricity for some electric streetlights and a few nearby private houses. Twenty years later, and electricity suppliers faced a problem: there were pronounced peaks and valleys in the demand for their electricity. Electrical consumption rose slightly in the early morning, fell to almost nothing during the day, and then peaked again as it got dark in the evening.

However, to meet morning and evening demand, suppliers had to continue generating at peak level output throughout the day. Big power stations can’t be adjusted up or down from hour to hour, and storing the quantities of energy they generate wasn’t (and generally still isn’t) practical or economical. Thus, a way to increase demand outside of peak hours was needed, and electrical appliances proved successful at doing just that. If you can’t, or don’t wish to, cut back production, then try to manufacture demand—the story of the twentieth century?

In the early 1900s, AEG (now known as the house-hold appliances manufacturer AEG-Electrolux) was primarily a generator of electricity. In 1907 Peter Behrens, perhaps the first industrial designer, was hired as a consultant to find ways to increase demand for electricity during the day. His solution? The first electric kettle, developed for AEG and produced in 1909. That year is also considered by those in the know to be when the first commercially successful electric toaster was launched by the Edison General Electric Company, the model D-12. When this toaster hit the shelves, I imagine it would’ve been regarded as a rarefied luxury, purchased by those early adopters at the forefront of the technological wave. Something like the iPhone is now—though making this comparison will quickly age this book. By the time you read this, the iPhone will of course have been superseded by the super-iPhone or somesuch, just as early toasters were superseded by the dual-side toasting, self-timing pop-up toasters, which in turn will also likely be superseded by as yet undreamt of toasting sophistication (unless, to use Doors front man Jim Morrison’s memorable phrase, “the whole shithouse goes up in flames,” or people just stop liking toast).

Anyway, at the time of the first toaster’s development, the additional convenience it provided would’ve been a boon. Toast without stoking the coal-fired range? How terribly marvellous! One doesn’t even require one’s butler! A hundred years on, however, and the electric toaster is mundane and common throughout much of the world. Amongst the jumble of products and services we are now surrounded by, the humble toaster’s function seems inconsequential.

Toaster production, however, is no longer inconsequential. The industry that produces them (and all of our other stuff) has grown such that the ability of the natural environment to accommodate it is being strained in a whole variety of ways. Even on a planet-sized scale, its effects are no longer trivial. The contrast in scale between this globe-spanning industry and many of the inconsequential products we use it to make seems a bit absurd—all of this, for toasters?

Are toasters ridiculous? Close up, a desire (for toast) and the fulfilment of that desire are totally reasonable. Perhaps the majority of human endeavour can be reduced to the pursuit of additional modicums of comfort—like being slightly less tired, being slightly less bored, or just an evenly crispy piece of toast—small trifles, to which we quickly become accustomed. This millennia-long striving to better our lot has thus far enabled more people than ever to buy a toaster (amongst other notable achievements). I really appreciate being comfortable and living when and where I do, and I’m also generally quite a fan of technology. But it feels like some things make such a marginal contribution to our lives that we could do without them and not even notice. This begs the question of what goes and what stays, and I can already imagine the arguments over whether hair straighteners are more or less essential than electric shavers. So far we’ve settled things by simply voting with our wallets, and it seems the clear winner at the ballot box is more rather than less. But what if some of the things we’re voting for aren’t being entirely candid about their origins? What if much of the cost of making them is hidden from us, or falls unequally on someone else? What if the vote is distorted?

The toaster serves as a symbol, my figurehead for the stuff that we use but is maybe unnecessary, but then again is quite nice to have, but we wouldn’t really miss, but is so relatively cheap and easy to get that we might as well have one and throw it away when it breaks or gets dirty or looks old.

So that is “why a toaster.”

Well that, and because I really like Douglas Adams: “Left to his own devices he couldn’t build a toaster. He could just about make a sandwich and that was it.”

This quote is taken from Mostly Harmless: The Fifth Book in the Increasingly Inaccurately Named Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Trilogy.

Our hero, Arthur Dent, a typical man from twentieth-century Earth, is stranded on a planet populated by a technologically primitive people. Arthur expects he’ll be able to transform their society with his knowledge of science and modern technology, like digital watches, internal combustion engines, and electric toasters, and thus be acknowledged as a genius and worshipped as an emperor. However, he realises, that without the rest of human society he can’t actually make any of it himself. Except, of course, a sandwich, one of which he happens to make himself one afternoon. This never-before-seen advance in eating technology so stuns the villagers that they promptly elevate Arthur to the high office of Sandwich Maker, whose sacred duty it is to hone and research the advanced art of the sandwich.

I read this book when I was about fourteen. The passage must’ve had a great effect on me to linger in the synapses of my brain only to resurface a decade later as the inspiration for my second-year master’s project.

My god. What would I do if I crashed on a strange planet? How would I even make a knife? What Adams draws on—a remarkable lack of knowledge about the basic technologies that underpin our modern existence—is true for most of us today. The idea that modern society divorces people from practical ability is not new, and usually carries negative connotations. Imagine a sci-fi film on the topic: Toast. Plot: The dust settles and surviving United Kingdom residents realise that although well versed in the health and safety implications of improper typing ergonomics, they don’t actually know how to make anything. How would people toast bread in this post–apocalyptic world?

Is it possible I could avert this disaster by reverse engineering a toaster, examining its constituent parts and materials, and recording my attempt to construct a duplicate from raw materials, using only the tools that might be available in post-crash civilisation?

And that is another reason why I want to build a toaster.

The Royal School of Mines, Imperial College, London

Senior Common Room

Friday, 7 November 2008 (Lunchtime)

My meeting with Professor Cilliers continues . . .

PROFESSOR CILLIERS: OK. So can you have some people doing stuff for you, or do you insist on doing it all yourself?

ME: Well, I want to make it myself...

And how set are you on the materials being comparable to modern materials?

[Silence... I’m quite set on it.]

Right. Well, if you use metals that are different they’ll be more expensive but much easier to produce. So iron and steel, everyone uses iron and steel for everything because they’re cheap, they’re produced in such vast quantities. For you to make iron and steel it’s going to be, err, a real bitch. But if you were to use copper, well that could be quite feasible because you don’t need high temperatures. That’s why we went through the Bronze Age first, because it’s piss easy to do.

Right.

Well the other thing is... you can say, well, can I use electricity? Do I have to make that myself? Can I use acid, do I have to make that myself? Just how far are you going to the root of the problem?

Well, I’ve got these rules...

THE RULES

The rules of the project are all-important. Of course I could make a toaster by going down to the Maplin Electronics shop, buying some Nichrome wire to bend into an element, buying an electric cord and a plug and wiring the whole lot together. Or I could make a toaster by sticking a piece of bread on the end of a stick and holding it over a fire. But that would be cheating...

Rule 1.

My toaster must be like the ones they sell in the shops.

What is a toaster? An object that toasts bread. A fire toasts bread. A fire is not a toaster. Why is a fire not a toaster? A fire is not a toaster because when you ask in a shop for a toaster, they don’t sell you a fire. Thus,

A. It must be an electric toaster that plugs into the mains electricity supply.

B. It must be capable of toasting two slices of bread, at the same time, on both sides at once.

C. It must be what is commonly known as “a pop-up toaster.”

D. It must toast bread for varying amounts of time.

Of course the ones they sell in the shops come in a wonderful array of shapes and colours (except they don’t, being mostly some variant on white or silver, and some kind of rounded cuboid roughly the size of a small terrier dog). They do come in a wonderful array of prices however, from £3.94 to £166.39 ($6.10 to $259.33)—which is quite a price range for a single type of product in the same shop.

Guided by my (evidently misguided) belief that cheapness begets simplicity, I chose as my exemplar toaster the:

Argos Value Range 2-Slice White Toaster

Cat. # 421/9608 £3.94

—

Which includes:

• Coolwall

• Variable browning control

• Mid-cycle cancel

• Cord storage

—

A great value toaster, which embodies the centuries

of incremental technological development, rising material wealth, and diverse global supply chains on which modern life depends. A must for any well-appointed kitchen!

It doesn’t have a crumb tray, though.

Rule 2.

I must make all the parts of my toaster starting from scratch.

What does from scratch mean? From scratch means making something starting from the very beginning. What does starting from the very beginning mean? Starting from the very beginning means starting with nothing. Oh dear, my mind wanders...

I cycle to some remote woods with a deep lake, dismount my bicycle, and throw it in the lake. Then from my pocket I take a box of matches containing a single match, and a small bottle of petrol. I take off my shoes and all my clothes, pile them in a heap on the ground, pour on the petrol, carefully light my single match, and . . . I’m naked in the woods and I’m making a toaster, from scratch. As anyone who’s paid the slightest attention to Ray Mears’s BBC series Extreme Survival knows, the first thing to do in a survival situation is find shelter and water. Then food. Once those essentials are sorted out, I can begin the long process of making clothes and the first tools that eventually will lead to the creation of my electric toaster.

But perhaps even this isn’t enough—the apple pie recipe of noted astrophysicist and archetypal 1980s science documentary presenter Dr. Carl Sagan rings in my ears: “If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.” The enormity of my task freezes me in my tracks.

Luckily, my naked contemplation of Dr. Sagan is interrupted by some startled ramblers, who report me to the local constabulary. I’m apprehended and receive a caution for breaching the peace and a small fine for contravening bylaws by starting a fire in a national park. They do, however, give me a lift in their police car back to the real world...

I’m making a toaster from scratch, and I live in London, in the United Kingdom, in the twenty-first century. I still want to sleep in my own bed, watch TV occasionally, and use the web to find stuff out, so I decide that from scratch means from the basic ingredients; that is, from the materials as they come out of the ground.

Rule 3.

I will make my toaster on a domestic scale.

I must make my toaster myself using tools that aren’t fundamentally different from those that were around before the Industrial Revolution. This is because if I went and collected a bunch of ore from a mine, took it along the road to a smelting plant and had it smelted, then took the refined metal to a wire maker to have it made into wire . . . well, I wouldn’t be making a toaster myself, would I? I’d be paying other people to use their very expensive and very complicated tools to make me a toaster. Besides, I don’t have the money.

I want to make my toaster myself, on my own. This means I’m making an object that’s usually produced in huge numbers in huge factories, singularly: a domestic object made on a domestic scale.

Thus, I decide:

A. Travelling overland is allowed because cars are just modern versions of horses. Flying is not allowed because human flight is a complete break from the past, with no pretechnological equivalent.

B. Using some domestic hand tools is allowed, even, say, an electric drill, because it just replicates a manual drill but is a lot quicker. Of course, using 3D-design software and a robotic milling machine is not.

So, with my rules logically infallible and set in stone I can begin.

The Royal School of Mines, Imperial College, London

Senior Common Room

Friday, 7 November 2008 (Lunchtime)

Professor Cilliers continues to ask his difficult questions...

PROFESSOR CILLIERS: When you look at what the old miners did, they smelted rock, but they started with a very high-grade ore. High-grade ore just doesn’t exist anymore. You’ve got to understand that typical ores have half a percent copper in them. So say we want a kilogramme of metal, we’ve got to treat a tonne of ore. Even for small-scale stuff you need quite a lot of rock. Can we find a lump of ore that has enough copper in it... there are mines that are rich in copper... if you go to Finland. The north of Finland. It’ll take you a week. So you get the copper, and you plate it out into sheets and hammer it into the shape for the casing.

ME: The toaster I had in mind has a plastic casing.

And you need plastic for what?

To make it look like a toaster.

Well, I’m a metal man.

Well, the internal bits are metal.

The problem with plastic is that it’s from oil. That technology is quite hard. That’s why we didn’t go through the Plastic Age before the Bronze Age, you know.

Right. I see.

If you look at those really groovy toasters, the handle comes out... um...

Dualit!

There we go, yeah. See, if you make a Dualit one, you need very little plastic. Lots of metal.

I sort of decided to model my toaster on a cheap one from Argos. They have a plastic casing, you see.

OK, so, you need a casing of some kind. Then you need an element.

Toaster elements I heard, or actually read, are made out of an alloy of chromium and nickel. And I looked around and I think there’s a nickel mine in Siberia...

The nearest high-grade mine is probably in Turkey. But then you’ll need a tonne, so... Anyway, then you need to get electricity to the element.

Copper wires.

And you need something to wrap the element around so it doesn’t catch fire, basically.

I think in toasters they have some sort of mineral or something.

Yes, it’s mica. Well it used to be, I don’t know if they still use mica or some modern synthetic substitute now.