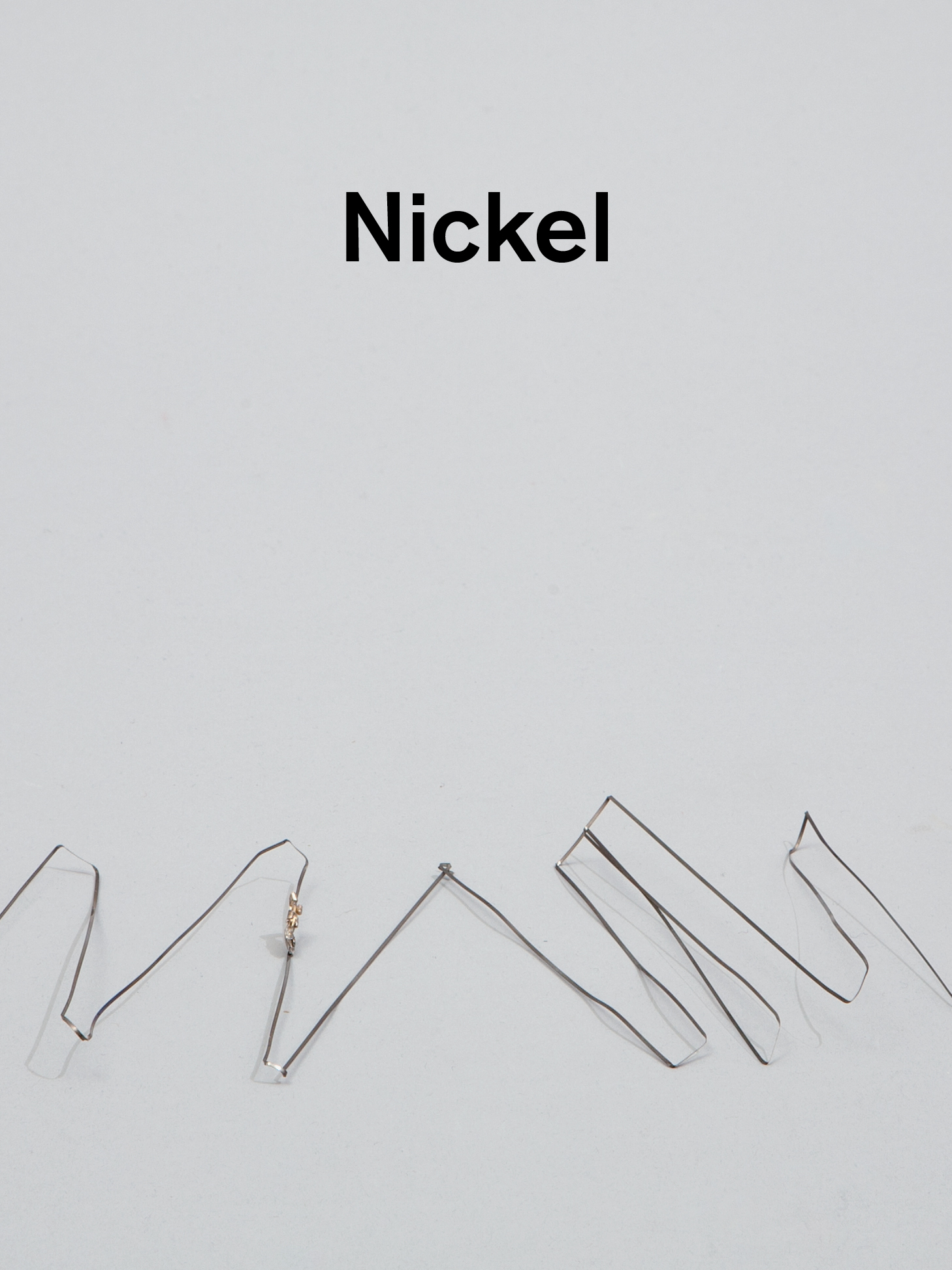

Nickel

I have a problem.

Nickel is essential to make the toaster element, but I can find only one site where nickel has been mined in the United Kingdom, and this mine has a big metal grate covering the entrance. There is scant information about it. My confidence hasn’t been buoyed by the responses I’ve been getting from people I’ve spoken to along the way when I ask them about finding some nickel ore within a sane distance of my house.

There is a large nickel mine in Siberia, in a place called Norilsk. This is Siberia’s northernmost city, sited on top of one of the largest nickel ore deposits in the world. For a city to exist in such a harsh climate (the average temperature is minus ten degrees Centigrade, with blizzards for 110 days a year) it needs a pretty good reason. The exploitation of the nickel deposit has provided one since the 1930s, though much of the exploitation until 1953 (perhaps even as late as the 1970s) was done by the forced labour of political prisoners, sentenced (either with or without a trial) to mine nickel in incredibly dire and often fatal conditions. Nowadays, Norilsk has the slightly less (or more?) dubious honour of being one of the ten most polluted places in the world (as listed by the New York environmental NGO, the Blacksmith Institute). The smelting of the nickel ore is done on-site, and because of the plumes of sulphur dioxide released in the process, allegedly not a single tree grows for fifty kilometres around the smelting complex, and the topsoil itself has become so contaminated with heavy metals that it would now be economical to mine as well. Sounds rather bleak.

It is a rather difficult place to go without a very good reason, and not just because it’s in Siberia. According to the internet, the Russian government has decreed Norilsk a “closed city” to foreigners.

My blog exposure has led to an interesting nickel contact however—someone with connections to the Talvivaara Mining Company, which is just starting to mine a large deposit of nickel ore in the far north of Finland. However (according to the Talvivaara PLC website), the extraction of nickel from the ore won’t happen in the usual way—that is, smelting it in a fur-nace and emitting plumes of acid-rain-causing sulphur dioxide-—but in a more environmentally benign way, using a process called “bio-heap leaching.” This involves heaping the crushed ore in a big pile and then using a variety of the same extremophile microbes that cause the water pollution problems at mines like Parys Mountain or Rio Tinto to actually extract the metal. A mixture of acid and extremophile, acid-loving bacteria, is sprayed onto the heaps and trickles through, the bacteria digesting the ore into more acid, sulphates, and nickel. The acid leaches out further nickel, and the whole nickel-rich liquid is collected in channels running under the heaps. One then has only to precipitate out the metal dissolved in the acid solution and voilà—all without so much unpleasant burning of fossilised trees and production of noxious gasses. Excellent, I think, bio-heap leaching is the kind of clever win-win solution us modern humans come up with these days: we get nickel for our toasters, and our bacterial partners and co-inhabitants of Spaceship Earth get a good square meal. Except, as it turns out, it’s not that simple. The metal products produced at Talvivaara still need to be smelted in the end. The reason bio-heap leaching had to be employed is because the ore mined at Talvivaara is of such a low grade—the concentration of metal is so low—that it wouldn’t have been economical to smelt, unless a cheap way was found to concentrate it first. This nascent technology of bio-heap leaching has found its first application in making un-exploitable ore worth exploiting.

Talvivaara has signed a ten-year contract to sell its nickel product (that is, concentrated nickel liquid) to none other than Norilsk Nickel. However, it’s not shipped all the way to the end of the world at Norilsk in Siberia. MMC Norilsk Nickel Group also own a nickel smelting plant at Harjavalta, in southern Finland. Unlike Norilsk, Harjavalta is not one of the ten most polluted places in the world. In fact, the smelting plant at Harjavalta has been studied as an example of an “industrial ecosystem.” Just as in natural ecosystems, where the waste products from one organism are the food source of another, the idea at Harjavalta is that the waste products of one industrial process form the raw material inputs for another. The idea of an industrial ecosystem is relatively new, and is an eco-system by analogy only, but it certainly seems like a move in the right direction. It’s interesting that although both are owned by the same company, Norilsk Nickel’s two smelting plants are polar opposites in terms of their environmental impact. Russia and Finland are also polar opposites in terms of their regulatory environments—one being one of the most corrupt countries in the world, the other one of the least.

Google says it would take me just thirty-six hours of continuous driving to get to Talvivaara from London. It’s also a good time of year to see the northern lights. But, I have two weeks before I need to toast at my degree show. I’m also at the very bottom of my overdraft. I consider my options:

A. Break into the alleged English nickel mine. However, as I’m carefully documenting the whole toaster-making process, this presents somewhat of a catch-22. If I break into the mine, which someone has taken such care to seal off, then I might find some nickel ore, or die. Either way I wouldn’t be able to tell anyone about it, because in the former case I would likely get done for criminal damage, and in the latter, well, it’s obvious.

B. Abandon my degree and travel to Siberia to get some nickel ore from Norilsk. (And possibly face arrest by a Russian policeman—what an exquisite irony however, if I was sentenced to hard labour in the nickel mines! Ha ha ha.) I also don’t have any money left to get there.

C. Hire a van and drive to the far north of Finland. Possibly see the northern lights, but possibly miss my degree show. Again, there is that problem of not having any money.

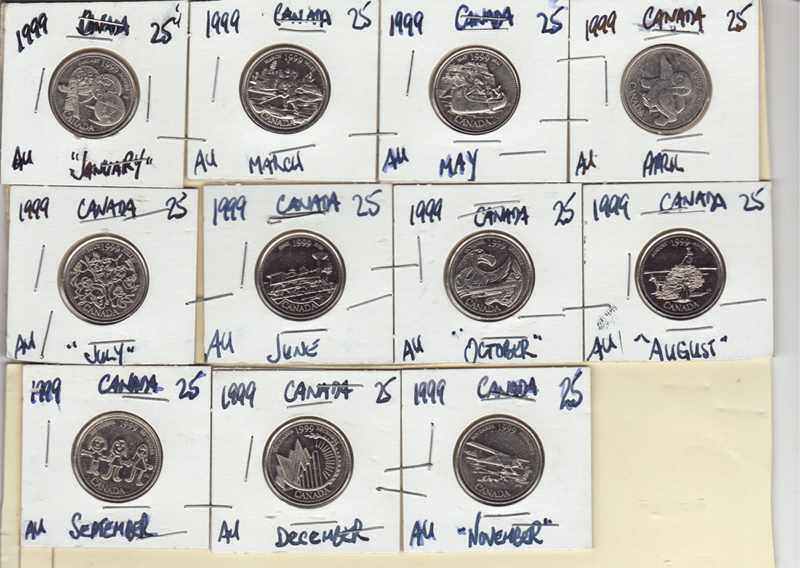

To be honest, none of the three options are particularly attractive/possible. In the interests of my future self I look around for other sources of nickel. I soon discover that the Canadian mint issued a special twenty-five-cent coin each month in the run-up to the year 2000. The twelve commemorative coins were made of 99.9 percent pure nickel.

Tempting. Especially when there’s a set of eleven being sold on eBay for only CAN $9.50.

Unfortunately, I may not avoid jail this way either, because, as the Royal Canadian Mint is at pains to reiterate, Section 11-1 of the Canadian Currency Act states:

No person shall, except in accordance with a licence granted by the Minister [of Finance], melt down, break up or use otherwise than as currency any coin that is current and legal tender in Canada.

The offence is not dependent on fraudulent intent. Oh well, what the heck. Unless I go to Canada, the mounties can’t touch me.

The eleven Canadian twenty-five-cent coins I won on eBay

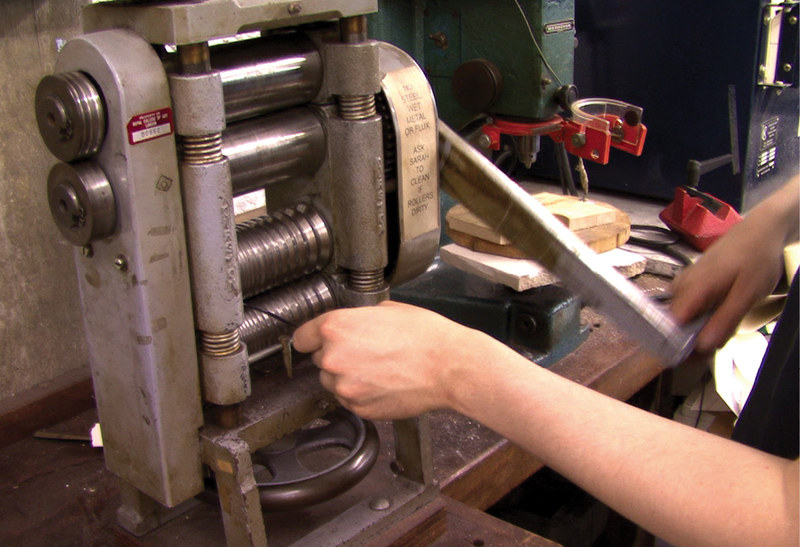

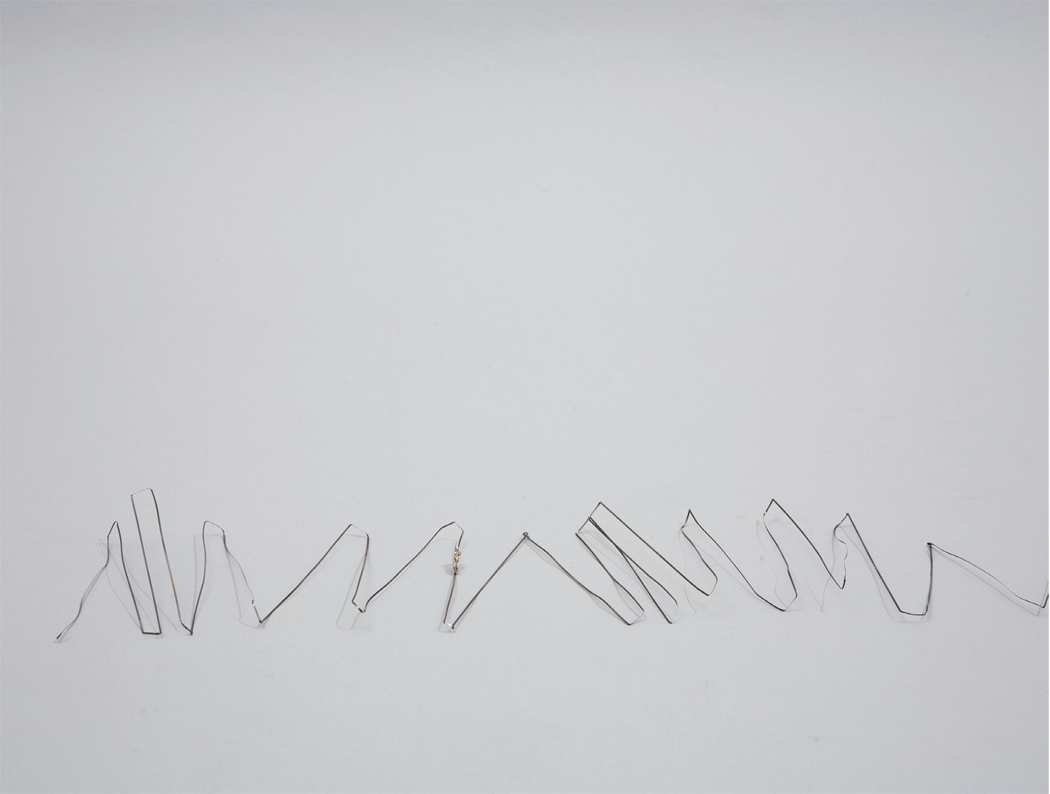

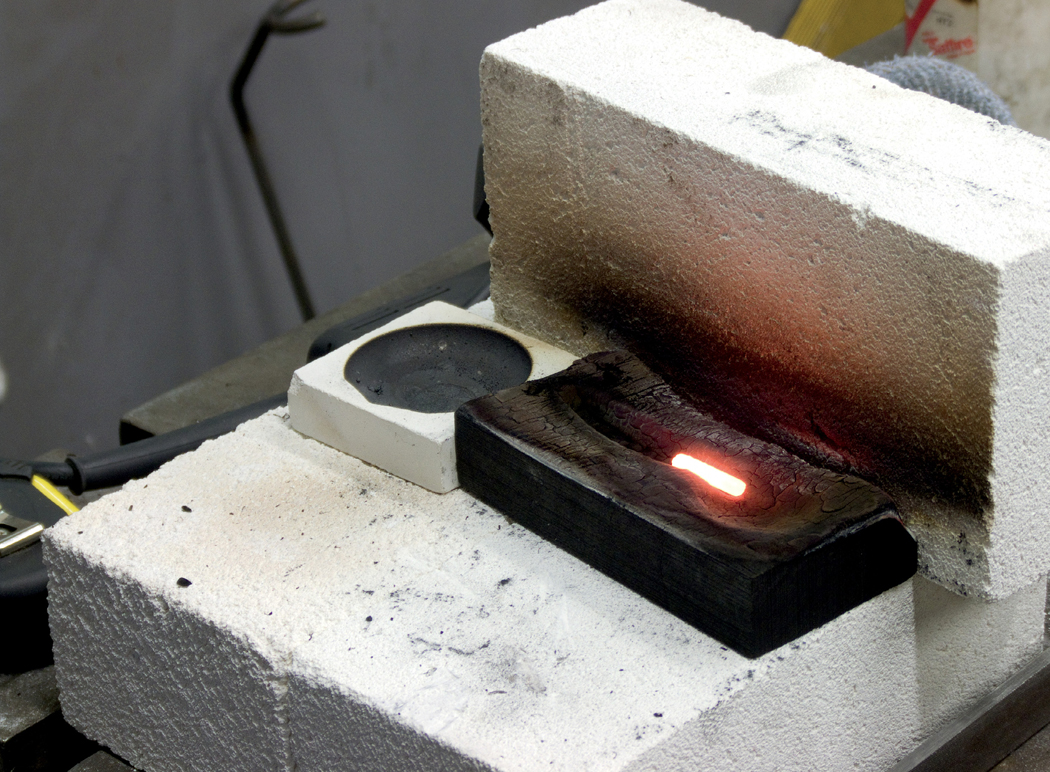

A melted Canadian nickel quarter ready for rolling into wire for the element