Not long before my first confession, my father had taken me aside and told me there was no point in my trying to keep secrets from the priest. A secret was just an unforgiven sin, he said, and besides, while I might fool the priest, I could never fool God, who knew even my most secret thoughts. I had seen the machine room at The Daily Chronicle, he said. Well, there was one just like that in heaven, except much bigger. There were thousands, millions of machines in it, just like the ones that automatically typed out the wire-service stories at The Daily Chronicle, the stories you saw in the paper with headings like Paris (AP), London (CP). On heaven’s teletype, he said, my heading was St John’s (DD). The entire record of my mind was being transcribed by some teletype machine in heaven. As soon as God saw the heading, St John’s (DD), he knew that what followed would be the secret thoughts of Draper Doyle.

For a while, I believed this, and dared not keep even my most embarrassing sins from the priest. I imagined God in some celestial machine room, reading my most secret thoughts the minute I thought them, receiving urgent bulletins from the mind of his St John’s correspondent, Draper Doyle. For all I knew, God was reading my mind aloud on some television newscast in heaven. The CBC. The Celestial Broadcasting Corporation. And now, the CBC news. With God. This just in: A reading from the mind of Draper Doyle. Or my secret thoughts were appearing on the front page of heaven’s equivalent of The Daily Chronicle. Imagine the readership. Imagine what an ad would cost.

As time went on, I had become more tickled by this notion than frightened by it, a fact my father somehow sensed, for he soon abandoned it in favour of another. I had been born, he said, with the black mark of original sin on my soul, which was otherwise pure white. It was the kind of black mark the puck leaves on the boards. Each time I sinned, another black mark was made. What I had to watch out for, he said, was that my soul did not go black before my time on earth ran out. For if it did, if it became what he called ‘puck black’, so black that no amount of time in the fires of purgatory could cleanse it, I would have to go to hell. The only thing that would keep my soul from going black before my time on earth ran out was confession. If, throughout my life, I made honest confessions, my soul would go to purgatory, he said, from which, when the cleansing process was complete, it would rise to heaven, with the souls of all those people whose sins had been forgiven. I imagined a host of white pucks, floating up like ash from purgatory.

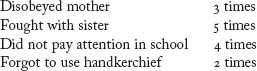

Even this notion, however, had not been enough to keep me forever honest in confession. In fact, by the time my father died, I was well advanced in the art of insincere confession. I had found that the best way to avoid blurting out the details of some real and possibly mortal sin was to compile, before going to confession, a list of imaginary sins, the rule of thumb for which was ‘venial and vague’. My list always looked something like this.

My ‘sinventory’, Uncle Reginald called it, when I showed it to him one day. It included only those kinds of venial sins that I knew grownups could imagine me committing – violations, in other words, of what Uncle Reginald called ‘the junior ten commandments’, most of which had to do with hygiene and obedience.

By the time Aunt Phil and Sister Louise intervened that November, I could compile a convincing sinventory in a matter of minutes. It turned out that displaying my stained underwear on the bulletin board in the kitchen was not revenge enough for Aunt Phil – perhaps she thought the real culprits, Mary and my mother, had gotten off scot-free. Though it was quite clearly Aunt Phil’s idea, it was Sister Louise who suggested that from now on my mother, Mary and I go to Father Seymour for confession. Sister Louise and Aunt Phil were already doing so, but the rest of us had been going to the parish priest. Going to Father Seymour, Sister Louise said, might help us get over our father’s death more quickly – she was only sorry she hadn’t thought of it before.

‘It’s been seven months now,’ Sister Louise said, ‘and, if anything, the three of you seem worse than ever.’ She looked pointedly at me when she said ‘the three of you’, then gave my mother a conspiratorial wink, as if to say that it was really only me that needed help, but that it might be hard to convince me to go to Father Seymour unless she and Mary did so, too. Once again, I looked to my mother to put a quick stop to what was clearly a bad idea. She seemed about to speak when Aunt Phil broke in.

‘I think it’s a wonderful idea, Sister,’ Aunt Phil said, as if, because we were living in her house, the final decision was more hers than ours. She got up and, before anyone realized what she was doing, phoned Father Seymour. ‘Would it be all right if Linda and the children went to you for confession from now on?’ She said, as if this was some special favour that our mother had been too shy to ask of him herself.

Aunt Phil soon after announced that, from now on, we would all go together to confession, the way another family might have gone for haircuts. We went once a week, on Wednesday, which became known as ‘Confession Wednesday’.

‘If sin was hair,’ said Uncle Reginald, who went to neither mass nor confession, ‘you’d all be bald.’

If sin was hair, Sister Louise said, Uncle Reginald would look like Rip van Winkle, with hair down to his ankles, using his beard as a scarf to keep him warm in the wintertime.

Why did it have to be our uncle who heard our confession? I asked Aunt Phil. Surely there was a rule against this sort of thing, people pouring out their sins to relatives, priests hearing the confessions of relatives with whom they would soon have dinner. Mightn’t a priest, in such circumstances, show favouritism, assigning less penance than was called for, doling out extra forgiveness to his inlaws? It might have been only this that worried me, to hear me talk, the possibility that we might have an unfair advantage over other people. At any rate, none of my arguments could sway her. We were lucky, she said, to have our own uncle to confess to – look at all the children who had to confess to total strangers. ‘Lucky them,’ I said, at which she flicked my earlobe quite painfully with her finger.

I was so distressed at the thought of going to Father Seymour, having to withhold from him such things as Momary dreams and buying my own underwear, that Uncle Reginald devoted a whole session of oralysis to confession. Why did I have to go to confession at all? he said. Why couldn’t I just mail my sinventory to Father Seymour and have him mail me my penance? That way, instead of having confession once a week, we could have it once a year. There could be a special form you had to fill out, just like the income tax form. ‘Sincome tax’ we could call it, he said.

Father Seymour, of course, would require signed receipts from all those people who had suffered at my hands. Uncle Reginald imagined me beating someone up, then asking for a receipt. ‘Received from Draper Doyle. One punch in the head’, signed, ‘Young Leonard. November 17, 1966’. I could send all my sins to Father Seymour once a year, to be audited by him. Then I would keep checking the mailbox for his reply, which would go something like this: ‘Please say this amount of penance – two thousand Hail Mary’s. (Please note the self-defence exemption clause. See Form 2A.)’

Despite oralysis, however, despite all my complaints, we went to Father Seymour. Every Wednesday, after Aunt Phil and our mother came home from work, before we had even sat down to dinner, we went to confession, all of us plodding guiltily to church where Father Seymour was waiting for us, all of us walking with heads bowed – and no wonder, said Uncle Reginald, with a whole week’s worth of sins on our shoulders, he was surprised we even made it to confession. Wasn’t it possible, I said, that we were overdoing it a little bit? – you couldn’t get balder than bald after all.

Aunt Phil assured me that you could never go to confession too often. Did I know, she asked me, that before I had even finished saying penance, sin was re-accumulating on my soul? Uncle Reginald was right, she said, in saying that sin was like hair. Even as the barber was cutting it, she said, your hair was growing, and even as the priest was forgiving you, even as you were saying your penance, sin was re-accumulating on your soul.

While Aunt Phil and our mother took Sister Louise to the sacristy where Father Seymour would hear her confession before he heard ours, Mary and I would kneel side by side in the pew. ‘Mary,’ I’d whisper, ‘we shouldn’t have to go to him,’ and Mary, as if she was fighting the urge to agree with me, to rebel against something her elders had deemed to be right, would make a face and put her hands over her ears. How well I remember them, our mother and Aunt Phil, coming out from the sacristy to take turns genuflecting, then kneeling together in the pew outside the confessional, waiting their turn with the rest of us. When Father Seymour had heard Sister Louise, he would come out across the altar, his confession stole about his shoulders, and hurry down one of the side aisles, taking great care not to look into the pews, acting as if he didn’t know that it was Wednesday, that among those penitents who were waiting for him was his entire family with whom he would have dinner afterwards.

Aunt Phil always went in first, then our mother, then Mary, then me. I remember my mother waiting with head bowed for Aunt Phil to finish, getting up to take the door which Aunt Phil held open for her. And I remember best of all that awkward moment when they met, the exchange of the door, Aunt Phil holding it until my mother had ducked beneath her arm, then releasing it and walking away as my mother closed the door behind her, closed it as silently as it was possible to close it, as if she wanted neither Aunt Phil nor Father Seymour to hear her, pulling the door shut by slow degrees and thereby drawing more attention to herself than if she had slammed it with all her might. It would go on for some time, that excruciating fidget with the door, after which, with the final click, the church was once again silent.

Minutes later, my mother would emerge to join Aunt Phil at the altar rail, where once again the two of them would kneel side by side, doing the penance which Father Seymour had assigned them, waiting each other out, it seemed, as if Aunt Phil, despite having several minutes’ head start on her penance, didn’t want to seem less devout by leaving first, and my mother did not want to make Aunt Phil’s penance seem shamefully long by finishing ahead of her.

Despite Vatican 11, Aunt Phil kept her head covered in church, and my mother, at her insistence, did the same. And though it was ten years since her husband’s death, Aunt Phil still dressed in black when she went out. My mother did, too, though it was understood that, come the first anniversary of my father’s death, she would stop doing so. Aunt Phil begrudgingly allowed that it was ‘acceptable’ for a widow to stop wearing black after a year, but her tone implied that a woman of real resolve and devotion would wear black forever. There they were, the two of them, each week, kneeling at the altar rail, wearing their bandannas, dressed so much alike that they might have belonged to the same order, or formed their own, an order of two, the Order of Philomena Clark and Linda Ryan. They would kneel there, far longer than it took anyone to say their penance until, finally, by some sort of signal of body language imperceptible to other people, they would get up at exactly the same time, genuflect together, then go back to the pew and wait for us to finish. Every Wednesday afternoon, this silent set of actions was repeated, exactly, ritually, as if it was part of the sacrament itself.

As for me, I dreaded what Uncle Reginald called my ‘two minutes in the box’ with Father Seymour. I hated the waiting. I remember the murmuring voices from inside the box, the church dark except for a trace of late-afternoon November light coming through the stained-glass windows, people going gloomily about. I didn’t always go in right after Mary – the rule was that any adults who were waiting went in ahead of children. But Father Seymour always recognized my voice – I could tell by the tone of his voice, in which there was a warning against my being in any way familiar with him. The worst part of it for me, aside from the sheer embarrassment of confessing to a relative, was that I was now forced to confess some real sins, for I had to include in my sinventory those sins he had seen me committing, or those he was likely to have heard about from someone else, be it one of the boys of Father Seymour’s Number, or Aunt Phil, or even Sister Louise. ‘Anything else?’ he kept saying, ‘anything else?’ whenever I paused on the sinventory, as if there was some particular sin he was waiting for, as if he had his own list on which there were still some sins I had yet to confess, still some not crossed off.

In this manner, he teased from me a confession of wetting the bed those first two times. It hardly seemed possible that this was the ‘sin’ he was waiting for, since even by the loosest definition of the word it wasn’t one, but when I mentioned it he seemed satisfied, and then gave me my penance. Every week it went like this. ‘Anything else?’ he’d say, and I’d rack my memory in search of what other sins he might possibly have heard of me committing.

Even worse than confession was the meal that followed it, to which Father Seymour was always invited; his reward, it seemed, for forgiving us our sins. It was clear from the way he carried on that Aunt Phil had not told him about the underwear episode. No man, no priest especially, in the company of a woman who had worn his underwear on her head, would have been as cheerful as Father Seymour. He acted as if we should all have hearty appetites and be in an especially good mood because we had just been to confession. As far as I could see, the only one in an especially good mood was him, which was understandable, for I would have paid any amount of money for the chance to sit around, having dinner with people who had just poured out their sins to me. I’d have been certain to get the upper hand in conversation. Father Seymour made such a show of not taking advantage of the situation that he made matters worse, his joviality only serving to remind us of what he knew, what he had on all of us, so to speak. We might all have been stark naked except for him.

Each week, I stared at my mother, wondering what she had told Father Seymour. Did she worry, too, about what Aunt Phil might or might not have told him? Did she confess things because she believed he already knew about them? Did she worry that if she told him something, he would tell Aunt Phil? Surely not, it seemed to me. Surely, between grownups it was different, altogether different. I stared at Mary, too, for she always seemed especially mortified. I tried to figure out which trap had claimed her this time. Had she foolhardily confessed to some embarrassing sin and was now regretting it, or had she given so glowing an account of herself that Father Seymour had guessed that she was lying?

I never felt more guilt-ridden than I did when leaving the confessional, what with all the lies I told while I was in there.

‘Nothing whets the appetite like a clear conscience,’ said Father Seymour. ‘Yes,’ I felt like saying, ‘and nothing dulls it like liver and onions,’ which was the standard menu on Confession Wednesdays. It must be true that virtue is its own reward, for every confession day Aunt Phil served liver and onions, with either bread pudding or what Uncle Reginald called ‘the spookie cookies’ for dessert. After the last day of a wake, Aunt Phil would bring home whatever snacks had been left behind in the kitchen at Reg Ryan’s. (Though the kitchen was provided by us, the snacks were provided by the mourners.) ‘No sense letting good food go to waste,’ she said. Sometimes there were sandwiches, but mostly it was cookies which, for the next several days, would constitute our dessert. The spookie cookies always filled me with revulsion. I could never quite put down the notion of the dear departed getting up in the middle of the night and going to the kitchen for a snack. It was bad enough eating food that you knew had been pawed over by the living.

How I dreaded those spookie cookies. They bothered me so much that Uncle Reginald devoted a full session of oralysis to Aunt Phil’s menu. He told me that I should not be surprised that Aunt Phil took better care of our souls than she did of our bodies, the soul being so much less expensive to maintain. He claimed that Aunt Phil was keeping the ‘good food’ for herself. When I looked dubious, he asked me if I thought it was pure coincidence that Aunt Phil was exactly as many pounds overweight as the rest of us combined were underweight. ‘The very fat of others on her bones,’ he said.

One of the worst Confession Wednesdays was Ash Wednesday, which happened to fall on my parents’ wedding anniversary. We, or I should say the others, ate dinner with what Aunt Phil called ‘the mark’ still on their foreheads. They were not allowed to wipe it off, but had to wait, Aunt Phil said, until it ‘faded naturally’. ‘Remember Man that thou art dust and unto dust thou shalt return.’ What I remembered was Father Seymour’s thumb, making the sign of the cross in cold ashes on my forehead. Ashes, Young Leonard had told me, from the Protestant crematorium. Only in death, it seemed, only when reduced to ashes, were Protestants of any use to Catholics. We were walking around with human remains on our foreheads, Young Leonard said, a thought which seemed to please him to no end.

Well, I decided that the others could do as they wanted, but I was not about to wait until some dead Protestant ‘faded naturally’ from my forehead. After confession, just before dinner, I put my head beneath the bathroom tap and washed some poor soul down the drain. Then I got one of those magic markers and dabbed the sign of the cross on my forehead, hoping that this would pass for ashes. I felt even more guilty than usual throughout dinner, waiting for someone to notice that I had magic marker on my forehead. There we sat, just back from confession, all with black smudges on our foreheads, guilt vying with a kind of morbid gloom for the upper hand, the six of us (Uncle Reginald was there, but Sister Louise could not make it) eating our liver and onions, after which Aunt Phil came out of the pantry with an especially mouldy-looking batch of spookie cookies.

‘I’m not eating them,’ I said. ‘No way. The liver and onions were bad enough. Why do we have to have liver anyway?’

‘It’s good for you,’ Aunt Phil said. ‘There’s iron in it.’

The iron, said Uncle Reginald, was what made it so hard to chew. And being hard to chew made it good for boxers, for it built up the muscles in their jaws, thereby increasing their ability to absorb punches in the face without losing consciousness.

‘Great,’ I said, ‘that’s all I need. An iron jaw.’

‘Eat your cookies, Draper Doyle,’ Aunt Phil said.

‘No,’ I said, ‘I don’t want to.’

She then launched into a lecture on Father Francis, who lived, she said, ‘below the equator’, making it sound like he was underground, or below the world’s paraline perhaps, where everything was dead or dying. ‘Not everyone in this world enjoys the advantages that you do, young man,’ she said. ‘Look at poor José.’

Poor José – that seemed to be his name, for it was never just José – was a boy my age who lived in the village in South America where Father Francis’s mission was located. I was sure it was no coincidence that, ever since I had started seeing my father’s ghost, Father Francis had been writing to Aunt Phil about poor José, describing the awful conditions in which he lived. Getting up from the table, Aunt Phil went to the sideboard and came back with several of Father Francis’s letters. She looked pointedly at me. ‘Father Francis wrote directly to you, young man,’ she said, as if this fact alone should shame me into eating all my food.

‘My dear Newfie Nephew,’ Aunt Phil read. ‘How are you? I am feeling fine.’ There followed yet another instalment of the miseries of poor José. (The Miseries of Poor José. It sounded like the title of some wretched novel, said Uncle Reginald. The Miseries of Poor José by Father Francis.) His life had not changed much since the last letter. Poor José never got enough to eat, had so few clothes that he had to wander around half naked all the time, had no school to go to, no church to attend, no home to speak of. Poor José, Aunt Phil said, had to use the bathroom outdoors while all sorts of wild animals were watching. I told her that, while all of this might be true – and I stressed might, for I suspected that poor José was a product of Aunt Phil’s imagination – none of it was my fault.

‘I never said it was your fault,’ Aunt Phil said. ‘But imagine if poor José knew about all the food that you were wasting.’

‘But he doesn’t know,’ I said. ‘Not unless Father Francis tells him. In which case, it’s Father Francis’s fault, not mine.’

‘Young man,’ Aunt Phil said, but Uncle Reginald came to my rescue.

‘What possible difference will it make to poor José,’ said Uncle Reginald, ‘if Draper Doyle eats all his food?’ He went on to wonder if it would comfort poor José to know that I stuffed myself to bursting night after night. Were bulletins being sent to the poor people of South America by the hour, keeping them up to date about what percentage of their food the children of the Western world were eating? Was there a giant score board, perhaps, by which the starving masses of South America kept track of their favourite eaters in North America? To hear Aunt Phil talk, he said, I had my own following in South America, a kind of fan club that watched my meals the way people in our own country watched sports events, deriving some strange, vicarious satisfaction from every morsel I managed to force myself to eat. ‘What do you think poor José would be like,’ said Uncle Reginald, ‘if he was in Draper Doyle’s shoes?’

‘He’d thank God he had shoes,’ Aunt Phil said.

Aunt Phil had often tried to convince me to answer Father Francis’s letters, telling me that his work was so hard that his spirits were often very low. About all I knew about Father Francis was that the rules of his order required that he keep his hood up all the time, even indoors. I couldn’t imagine what it would be like in the heat of South America to have to keep my hood up. There were twenty priests at the mission, and all I could picture, when Aunt Phil mentioned Father Francis, was twenty grown men with hoods up, having dinner. I was sure that nothing I could say to a man living in such circumstances would cheer him up.

‘Maybe you’ll answer this one,’ Aunt Phil said, when she finished reading.

I said nothing.

Aunt Phil put the letter back in the envelope and looked at Uncle Reginald. ‘The child’s impudence I can understand,’ she said. ‘But you should—’

Just then, without warning of any kind, my mother put down her fork and started to cry. As if this was the prearranged signal that the meal was over, Aunt Phil got up and began to clear the table. We sat there, Father Seymour, Uncle Reginald, Mary and I, trying very hard to look as if it was entirely normal for someone to burst out crying at the dinner table, or perhaps as if no-one was crying at the dinner table. When our mother leaned her ash-smeared forehead on her hand and continued to cry, Mary pushed back her chair, stood up, and raised a glass of water in front of her. It might have been something that, all throughout the meal, she had been trying to work up the nerve to do, at first waiting for the right moment, then, having allowed all the right moments to pass, waiting for the least inappropriate moment. Finally, at exactly that moment when to stand up and propose a toast would be the worst, most mortifying thing to do, she had jumped to her feet and, all but weeping with embarrassment, blurted out, ‘A toast to Mom on her anniversary.’

‘No, Mary,’ our mother said, shaking her head and motioning for Mary to sit down. She began to wipe her eyes and, as if to prove that she had stopped crying, she smiled, but Mary pressed on.

‘A toast to Mom,’ Mary said, looking about in panic for someone to join her. She looked beseechingly at me, as if to say that for me to let her down at this moment would be unfair, even by the standards of the war that we had been waging against each other since I was born.

I looked around the table. Aunt Phil, who seemed not to have noticed that Mary was in mid-toast, went on clearing the table. At last Uncle Reginald stood up and solemnly held out his glass of water, winking at my mother as he did. Then Father Seymour rose, and, smiling indulgently, as if to say that toasting your mother with a glass of water was a lovely gesture, raised his glass, at which my mother reddened and, once again starting to cry, asked Mary to sit down.

Mary looked at me again, at which point I stood up, held up my glass, and said, ‘A toast to Mom.’

When I tried to touch my glass to hers, however, she pulled away and, smiling, said, ‘Not yet, Draper Doyle.’

Our mother sat there, staring at her plate.

‘Mom,’ Mary said, ‘I’d just like to say—’

Her voice broke and she paused, concentrating on the glass of water. ‘I’d just like to say—’

Her voice breaking once again, she stopped. Her bottom lip began to quiver and her eyes welled with tears.

‘Mom, I’d just like to say that you’re—’

Before she could say another word, Aunt Phil reached out and, quite matter-of-factly, as if Mary was extending it to her, plucked the glass of water from her hand. The tears that Mary had been holding back came flooding forth, and as, with considerable embarrassment, the rest of us sat down, she went running to her room, our mother following soon after.