10

A VIEW FROM THE TOP

Evaluating the Solonian property classes

Lin Foxhall

INTRODUCTION

Solon and his reforms have fascinated many generations of scholars, as a puzzle with many critical pieces missing, and we have all been keen to exercise our ingenuity in restoring them. But the picture on it is vitally important, for it flashes by at a crucial moment in Athens’ development, essential to our understanding of her subsequent history, politics and institutions. How we perceive the constitutional, economic and political formation of the Athenian polis depends heavily on how we reconstruct what Solon did, and to or for whom. And how we interpret Solon depends most on what we think the Athenian polis was in the early sixth century.

In this chapter I will start by reviewing what I hope is a representative selection of the vast scholarship on Solon and his city. Next I will explore what exactly the polis might have been in the late seventh to early sixth century. I will then move on to the agricultural economies and settlement data for Archaic Greece in general, with the aim of contextualising what little we know of the agrarian economy of Athens in the context of a human landscape. Finally, I will focus on the system of property classes (the tele) attributed to Solon in the setting of the agricultural economy, and the view they offer us from the top of Athenian society.

PERSPECTIVES ON EARLY ATHENS

The problems with the sources for this early period of Athenian history are well known.1 The extent to which Herodotos or Aristotle understood Solon’s verse, or his motivations, or the world in which he lived, is questionable. For most of our Classical (fifth- and especially fourth-century) sources Solon and his laws were a political football which belonged to their own times. By Plutarch’s era Solon was part of a world that was lost. Whatever ‘truths’ may be preserved in these later sources, they cannot be reliably extracted from the later moral and political contexts in which they are expressed. Solon’s own poetry, quoted only in decontextualised fragments, is probably our best source, however inadequate. The tele, Solon’s property classes, remained a living (though not unchanged) institution at least into the fourth century,2 though it is hard to be sure how accurately later tradition represents the way they worked in Archaic times. The poetry and the inscriptions provide perhaps the clearest insights into what or who the Athenian polis was early in the sixth century, while the broader context is illuminated by the archaeological record. These sources do at least have the advantage of being mostly contemporary with the events and come, as it were, from the horse’s mouth, even if it is not always clear what they are telling us.

The Solonian polis (like Archaic Greece in general) has been a prime testing ground for many different approaches to reconstructing the overall development of Greek society: variations on ‘primitivist’, ‘modernist’, formalist and substantivist theory have all been tried.3 Most have been evolutionist to some degree, by which I mean they have typologised Archaic Athens as a stage, usually a fairly early one, in a general schematic framework of social development widely applicable to many societies. The idea that societies go through some predetermined succession of set stages is highly problematic and deeply questioned by current social theory.4 An evolutionist perspective is certainly implicit in the categorisation of Dark Age and Archaic Greek societies as, for example, ‘simple societies’,5 ‘chief-doms’,6 ‘tribal’,7 ‘small sovereignties’,8 ‘primitive society without strong central authority’.9 I am dubious whether such developmental typologising is helpful for understanding early Greece.

A related problem is that the evolutionary impetus behind many studies has encouraged teleological thinking. We all know that Athens eventually became a democracy, and modern scholars have often been tempted to fix on Solon as the ‘father of Athenian democracy’.10 This idea is also linked to the assumption that Solon was a revolutionary, at the head of a revolt generated from the bottom end of society.11 Although Solon may have triggered off political processes which eventually led to the emergence of Athenian democracy, it seems to me ludicrous that Solon had any inkling of this—it is just that we know the end of the story. Indeed, in recent writing on the earlier (eighth-century) emergence of the polis there is a tendency to perceive the seeds of democracy, or at least some kind of broadly based egalitarian spirit, behind the notion of polis itself:12

The truly remarkable aspect of the polis was the notion that the state should be autonomous from dominant-class interests. The ideal of the polis was almost a classless society, where the state and the citizens were identical, protecting one another’s positions. The direct democracy as found in classical Athens was possible only in a society where such a notion of the state was widely accepted.13

I have quoted Morris as a particularly clear example of this line of thinking, but it is implicit in the work of many scholars.14 Surely this must be at least partly a mirage arising because we know the Athenian end of the story. It is demonstrable that neither Archaic nor Classical poleis were inherently egalitarian (much less democratic). In most, even amongst the citizen body (the only arena in which any notion of equality might be postulated), some citizens were always ‘more equal’ than others.

Focusing on the Solonian scholarship, generally (though this is an over-simplification), older scholarship tends to be ‘modernist’ in tone (even if that entails seeing Solon as a ‘modern’ statesman confronting an archaic and ‘primitive’ political system), whilst more recent scholarship, depending more heavily on ethnographic comparisons and substantivist-influenced approaches, frames Solon in the context of ‘simple’ societies.15

16 for example, envisaged Solon as an informed politician, perhaps carrying out an ancient version of the modern Chrimes, Greek agricultural census in order to establish criteria for the tele, implying a fully developed state bureaucracy. Woodhouse perceived the political economy of seventh-to sixth-century Attica as one dominated by ‘the aristocratic capitalist… out…to absorb the peasant and his land’.17 Though Woodhouse’s Archaic Attica was not straightforwardly modern, it was unashamedly British mediaeval (e.g. the title of Chapter 12: ‘From Yeoman to Villein’), and its ‘primitive’ elements (e.g. the ’underdeveloped‘ concept of private land ownership18) were implicitly part of this mediaeval/pre-modern character. French carried this line of analysis to a crude extreme, hypothesising a kind of pro to-industrial revolution in the early sixth century on the basis of ill-informed macro-economic analysis of Attic agriculture (see below). With Solon’s reforms, he argues, an out-dated system of feudal patronage in which peasant-serfs no longer obtained security in return for the bondage of patronage was eliminated in one fell swoop.19 This change also benefited landlords, for:

The Hektemor would thus become a free labourer, with all the advantages and disadvantages that this implies. It would be an advantage not only to the olive and vine-growing industry, but also to the merchant and shipping interests to have a pool of casual labour, to be employed when the needs of harvest or business required, and dismissed when they were not required.20

In a less extreme way, Andrewes,21 Forrest22 and Starr23 all interpret the period as a time of ‘agrarian crisis’ solved by Solon, who incorporated the discontented poor into the privileges of the Athenian state. Starr most closely follows a formalist/ modernist line similar to French. The tele have been generally perceived as the means by which the poor could claim a share of power.24

Finley represents a new departure, working under the influence of Polanyi’s substantivist body of economic theory. However, he was most interested in illuminating the nature of the debt bondage which might have existed in Archaic Athens, and contextualising it within a much broader picture of dependent statuses and the socio-economic and political relationships implied by debt bondage, which characterised the societies of classical antiquity and the ancient Near East (though he was well aware that such features could be documented in modern, non-western societies as well). For all that Finley’s approach, particularly his use of comparative economic and social theory, has had a tremendous impact on the most recent studies of Archaic Greece, Finley himself was not very interested in the broader agrarian picture: his focus was firmly on status rather than on agro-economic conditions, and on land tenure over the long term rather than on systems of cultivation.25 Finley was still working within an evolutionist framework, regarding debt bondage as ‘an age-old principle common to both Graeco-Roman and Near Eastern societies in their early stages, and to many other civilisations as well’.26 These ‘many other civilisations’ are non-modern and non-western—‘them’, not ‘us’.27 Finley also drew an interesting (though I think misguided) distinction between systems of dependency and debt bondage in the Graeco-Roman world and those of the Near East: in the former, he maintained, ‘abolition came…as a direct consequence of struggle from below, at times reaching genuinely revolutionary proportions’.28 Though he is by no means the only scholar to uphold such a rosy view of Solon’s reforms, Finley’s formulation has probably had the greatest impact on current scholarship, especially the notion that Solon’s reforms reflected ‘struggle from below’.29

Much recent work, as Murray30 has also noted, has been influenced by the demographic conclusions developed from the archaeological record by Snodgrass, who long upheld the view that during the eighth century huge population increases occurred throughout Greece, the immense impact of which heralded the rise of the polis. Although many criticisms have been levelled at Snodgrass’s conclusions (based largely on numbers of datable graves), the basic premises are still generally followed.31 Indeed, it has been widely accepted that population pressure, ‘land hunger’, pressure on agricultural resources, and similar eco-demographic causes played a significant part in the troubles which afflicted Attica at Solon’s time. It will become clear below why I do not believe this.

The most recent studies have attempted to take more ‘anthropological’ approaches, though these have not been without their pitfalls.32 Gallant33 has drawn heavily on development economics, notably the theories of Boserup and Sahlins. The result, ironically, has been a conclusion very similar to the work he sees as diametrically opposed to his own—that of French. Gallant argues that because of population pressure elite farmers appropriated uncultivated land which was then worked by poor farmers at peak periods seasonally (at sowing and harvest) in return for one-sixth of the crop. The poor farmers, however, also worked their own land as well for subsistence. Both parties benefited while the system worked, the poor obtaining access to extra resources and patronage while the rich acquired labour, but the system ‘got out of hand’ and broke down.35 All of these processes are envisaged as taking place within ‘simple’, village-based societies.36 Most of the theoretical underpinning is based on African and South-East-Asian case studies.

Rihll’s discussion is a variation on the same theme. She focuses much more on the problem of land tenure—another leitmotif in Solonian studies. Rihll too assumes a fairly ‘simple’ society—her comparisons are largely based on ‘non-state’ societies, and again most of the anthropological studies she cites are African.37 Her central proposal is that the land taken over by the rich is ‘public’ land—on the grounds that ownership of land in ‘archaic’, ‘simple’ societies is grounded in the community and that private land ownership was not yet fully established in Archaic Athens. This idea, though interestingly argued, seems problematic on two counts: first, it is not at all clear what exactly ‘public’ means in this period—almost certainly not exactly what it meant in Classical Greece (and most of her secure examples of public land are Classical or later),38 and second, it is unquestioningly evolutionist, and quite unjustified, to assume that the public (or kin-group) ownership of land represents a more primitive social stage and therefore pre-dates private ownership in Greece (or anywhere else).

Similar criticisms can be levelled at Manville’s analysis, the most recent large-scale treatment of Solon and his reforms in the context of the development of citizenship in Athens.39 Like Rihll he seizes on land tenure as the core of the problem for Archaic Athens in the wake of population increases, changing crops and agricultural techniques (e.g. the introduction of tree crops), and concomitant pressure on agricultural resources necessitating even the import of grain for food.40 Oddly, though he argues against Snodgrass’s assertion that population increases played a major role in the ‘rise of the polis’ in the eighth century, he envisages population pressure as a critical factor in Athens’ problems during the seventh century.41 He draws heavily on the literature of development economics and cultural and social anthropology, largely from African chiefdoms and other kinds of ‘stateless’ societies.42 And, like Rihll, he maintains that much land was ‘held in common by kinship and regional associations, controlled by powerful elites in each organisation’,43 and was fundamentally ‘public’.44 Although he is sensitive to the complexities of land tenure, his fundamental premise is that a move toward more ‘private’ ownership and less ’public/communal‘ ownership characterises the development of Archaic to Classical Greece.45 None the less, a view of seventh-century agriculture which sounds suspiciously modern and almost industrialised creeps in, within a bleak agrarian outlook in line with the traditional views about the agricultural economy at this time:

Thus market producers were now investing much more capital to develop their lands than were subsistence farmers….

The greater risks taken by these entrepreneurial farmers would have made them more eager to secure title to their properties. Among this group private ownership was growing…46

Older and traditional common lands were slowly broken up; fields became more fragmented as successive generations of fathers divided them among sons who worked smaller and smaller plots more intensively…. Marginal lands were opened up for cultivation; other plots were abandoned as unproductive…47

Manville’s picture of Solon’s reforms is also typical in its depiction of the tele as ‘an all-inclusive legal hierarchy that embraced the entire community’ on the grounds of wealth, not birth, incorporating even the poor thetes.48 Assessment in wet and dry measures, he argues, reflects the importance of oil and wine in the economy.49

Even more recently, Victor Hanson’s attempt to trace the history of the polis as the history of its small and medium-scale farmers bound together in an ethos of ‘agrarianism’ takes refuge in many of the traditional views of Archaic Greece.50 Solon, he maintains, is one of those in the middle (mesoi) of the socio-economic scale, whose reform measures reflect the growing power of this group of egalitarian, ‘middling’ farmers in a time of agrarian crisis.51 He envisages its ultimate cause as population pressure, as Greece emerges from a Dark Age characterised by pastoralism practised by dominant aristocrats,52 hence smaller farmers became ‘homesteaders’,53 moving out of valley bottoms and onto more ‘marginal’ hill-slopes.54 This process, he argues, coincides with the invention of grafting and the introduction of vine and olive cultivation on a substantial scale.55

WHO WAS THE ATHENIAN POLIS IN THE SIXTH CENTURY?

Who or what is the Athenian polis of Solon’s time, and what comparanda can help us visualise it? As noted, most studies from Finley onward have looked to anthropology for help in invoking Archaic Athens. This is not to say that social theory is not valuable, indeed I am certain it is essential, but ethnography needs a health warning for ancient historians. Anthropologists have never studied a society like the Greek polis which is neither a kingdom nor a chiefdom, a state which is not a modern state, a society not ‘primitive’, nor yet linked into any global system dominated by powerful modern nation-states (as most ‘primitive’, ‘simple’ societies have in fact been since the nineteenth century). Undoubtedly Archaic Greece has features in common with many non-modern, non-western societies, and comparisons are illuminating when they are controlled and contextualised. But typologising antiquity into societies of ‘big men’, ‘shame cultures’, gift-giving societies, rank/order cultures, or whatever does not explain it.

Moreover, when we look at the comparanda most often used for the agrarian economy of Archaic Attica, the methodology appears alarmingly shaky. Most of the ethnographic case studies drawn on by Rihll, Manville, Gallant, Finley and others have come from tropical environments, usually Africa, South-East Asia, and the South Pacific. Generally they are societies which, though they may in themselves be ‘stateless’, have been studied at historical moments when they were either part of nation-states or the colonial possessions of large and powerful European empires. Not only are they linked into global systems, the like of which did not exist in the ancient world,56 but the agrarian and environmental conditions are totally different. For a start, many operate various kinds of tropical shifting-cultivation systems based on largely non-storable staples such as root crops. As used by Gallant, Rihll and Manville to understand early Attic land tenure, I would doubt that such analogies reveal much of the picture we aim to reconstruct.

I would argue that generally the poleis of Archaic Greece were little more than a stand-off between the members of the elite who ran them. The real question seems to be who constituted this elite and how did its make-up change over the course of our period? Obviously, individual cities and regions developed differently. And it is clear that in many parts of the Greek world we have good evidence of formalised magistracies, crystallising laws and other features of ‘state’ bureaucracies by the seventh century.57 But, even in Athens down into the fifth century, to what extent were offices differentiated from office-holders, and how much did particular office-holders shape the duties and privileges of the office they held?58

Magistracies and other state institutions might in many cases be little more than a means by which the elite took turns at power, giving some other group or person of equivalent status a turn, in order that they themselves might be guaranteed one later. Such groups might most likely be kin-, clan-, fictive-kin- and/or regionally-based, but the details for ancient Attica are lost in the mists of time and it is difficult to push the information which has come down to us about gene, phratries, orgeones, and phylai too far. However, the burial plots of competing groups (however they were constituted) scattered across the Greek countryside might also suggest such regional-/kin-based configurations of power.59 There is evidence (despite the unsatisfactory state of publication) for what seem to be such family-/‘kin’-based tomb groups in use throughout the Archaic period, not only in the large cemetery of the Kerameikos in Athens, but also throughout the rural landscape (e.g. at least two in Vari).60 The ethos of ‘the community of the polis’ perceived by Morris and others in early Greece might be only this: the egalitarianism of the equally powerful. The earliest known law, from seventh-century Dreros,61 seems to indicate precisely this sort of turn-taking amongst wealthy equals—no one is to be kosmos more than once in ten years. Even the later sixth-century archon list we possess from Athens,62 on which the surviving names date to well after Solon’s time, looks like rivals on the playground taking turns. Many more examples could be cited.

Such competing elite groups are pulled two ways at once: on the one hand, they aim to outdo their rivals, but, on the other hand, they share interests of group (virtually ‘class’) solidarity with them. Concomitantly oppressed groups of dependants are well documented in Archaic and Classical Greece. At one level the ragged bundle of institutions we call the ‘state’ in Archaic Greece is little more than the concrete outcome of the attempt to resolve these tensions.63 Tyranny is one logical outcome of such a system, for if one group becomes sufficiently more powerful than the others, then they can override the system: hence the tyrant Peisistratos was able to monopolise power by monopolising the archonship. Other members of the elite were most disadvantaged for their access to power was blocked.

Most early magistracies are non-specific in their duties, allowing considerable scope for office-holders to shape them according to their means and resources. Power, in these circumstances, represents a discourse between the expectations and threshold of toleration of peers, on the one hand, and the resources (in all senses) and cunning of the incumbent. Solon’s own poetry suggests that the man shaped the office:

Solon was not by nature a man of deep plots and clever counsels; when the gods gave him wonderful things he did not accept. He surrounded his prey but was so gobsmacked that he did not pull the great net to, and failed, stumbling in spirit and in sense. I wish I were strong and could seize wealth beyond the dreams of avarice and be tyrant of the Athenians for one day only, later to be skinned to make a wine-bag and my lineage wiped out.64

But another than I taking the goad, an avaricious man of bad judgment, he would not have checked the demos.65 …for if someone else chanced on such an office as this, he would not have checked the demos nor stopped it, before he had churned up the milk and taken away the butterfat, but like a boundary stone I stood fast in the disputed territory between them.66

Another man, says Solon, might have behaved differently when he had his turn at power at a critical moment.

The specific details of the changing social and political circumstances in seventh- and sixth-century Athens are beyond our reach. Solon’s poetry is enigmatic, and later commentators are muddled and meddling with the past for their own ends. Nonetheless, it is broadly agreed that Solon is portraying himself as, in his own words (fr. 37), the boundary stone (horos) between factions which he seems to categorise as men of means on the one hand and the demos on the other hand. This does, of course, make Solon look good—was this part of the aim, and can we therefore take this at face value? Most commentators, citing Solon’s own poetry, placed Solon firmly on the side of the demos: casting him as a revolutionary leader championing the cause of the poor.67 Exactly where in the socio-economic spectrum Solon himself originated is much debated and depends heavily on the theoretical perspectives of particular scholars: some kind of ‘middle-class’ birth is often postulated.68 However, the poetry can as easily be read as a viewpoint from firmly inside the elite, but with some sympathy (though I think he is rather patronising) for those outside the power-holding clique.69 Solon himself expresses the traditional values of the elite, for example: ‘Prosperous is he who has dear children, whole-hooved horses, hunting hounds and a guest-friend abroad.’70 This could have come straight out of Homer, and Xenophon, that landed gentleman of the fourth century, still felt much the same two hundred years later. On the other hand, many of his views of the demos could be read as positively paternalistic:

For I gave the demos as much reward as was sufficient for them, neither taking away privilege nor offering more.71

So best would the demos follow the leaders, neither let loose too much nor yet wreaking violence, for excess breeds insolence when much wealth follows for men whose mind is not perfect.72

insolence when much wealth follows for men whose mind is not perfect.For what reason did I gather up the demos only to stop before it happened?73

If it is appropriate to rebuke the demos openly, they have things now which they only saw in their dreams.74

The last is surely an echo in reverse of Macmillan’s ‘you never had it so good’. Indeed, fr. 24 offers a variant on this attitude, and mystifies the significance of wealth for wielding power, expressing the sentiment that ‘really, it’s just as nice to be poor if you are attractive’:

The one who has much silver and gold, plains of wheat-bearing land, and horses and mules is equal in wealth to the one who has this alone: that he is graceful in belly and ribs and feet. These things are resources for mortals, for no one with countless things ever came to Hades with them, nor paying a price could he flee death nor burdensome illness nor the evil onset of old age.75

I do not expect the bulk of hoipolloi would have agreed, then or now. This is a view from a comfortable house at the top. Who exactly he means by the demos is not at all self-evident. We have a reasonable idea what the term meant in fifth- and Who exactly he means by the demos is not at all self-evident. We have a reasonable idea what the term meant in fifth- and fourth-century Athens, but this does not guarantee that it meant the same thing in the seventh or sixth century, though many commentators assume it does.76 That it represents the poor in any kind of absolute sense, or even simply ‘the lower orders’, or (with Hanson), those of middle rank, cannot be securely ascertained. After all, we have evidence of the term demos in Mycenaean Greek, probably meaning something like ‘village’, but no one would claim that the meaning remained unchanged in historic times. Nor need the term demos in Solon’s time carry the same significance for the concept of ‘public’ which it does later on—indeed, the whole question of what ‘public’ might have meant in the early sixth century is problematic if I am right that offices and office-holders are not fully separable—if so, the ‘state’ certainly does not belong to the ‘demos’ as it did under Athens’ radical democracy of the fifth and fourth centuries. It is suggested by Solon’s poetry that at least part of the cause of strife is something to do with access to land, whatever the practical details of removing the horoi and freeing the black Earth might have entailed.77 What or whose land remain largely unanswerable questions.

AGRICULTURAL SYSTEMS IN EARLY GREECE: A REASSESSMENT

Solon’s arbitration of the troubles of his time must have amounted to (re)defining who the elite were so that the comfortable turn-taking of power might be re-established on a ‘new’ basis. This is epitomised by the tele. Why his ‘reforms’ were needed remains problematic: although many attempts have been made to outline detailed scenarios of the contemporary political situation, our information is inadequate for analysis at the level of historical event. On the other hand, the economic foundations and the agrarian structures of Archaic Greece can be profitably explored.

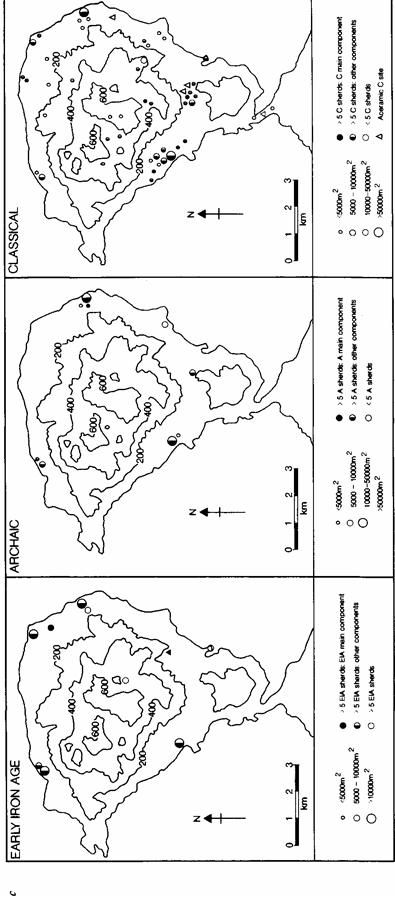

The archaeological record provides the most useful source material for this period, though it is by nature largely unsuitable for reconstructing political history. The evidence of increasing numbers of sites from the eighth century has generally been interpreted as a demographic phenomenon: it is also, of course, an economic one. We are, after all, talking about identifying datable graves and significant amounts of datable sherd material on surveyed sites, sanctuaries, and so forth (and Late Geometric pottery even in very small fragments is easily datable compared to Early Geometric, Middle Geometric and even most Protogeometric). Increased levels of material prosperity, whether or not this accompanies substantial population increase, will produce such an archaeological record. And the increase in datable material does not stop in the eighth century. Though firmly dated seventh-century graves are less numerous than eighth-century ones in Attica,78 there is abundant evidence for the production and export of seventh-century pottery (notably SOS amphorae), even if Protoattic fine-ware is problematic.79 There is plenty of activity at sanctuaries.80 In the absence of systematic intensive surface survey, difficult in much of Attica, I think it is impossible to determine whether the decrease in the number of non-burial sites in Attica between the eighth and seventh centuries81 genuinely results from economic or demographic phenomena, or whether it disguises some other political or demographic process (e.g. increasing nucleation, changes in the use of sanctuary sites, or whatever). By the early sixth century (whether before or after Solon is impossible to tell—the pottery dates cannot provide that level of fine tuning), black-glazed and black-figure Athenian pottery is everywhere.

Attica is a difficult area for multi-period archaeological survey. Much of the landscape close to the heart of Athens has been heavily developed from the Classical period onward. Lohmann’s survey work in a dry, indeed marginal, part of south-west Attica (the territory of the Classical deme Atene) reveals much Classical and Late Roman use of the landscape, but very little Later Bronze Age, Dark Age, and Geometric through Archaic exploitation. There is no evidence here for seventh- or even sixth-century expansion into the less productive parts of the Attic countryside: the exploitation of this area peaks in the fifth and fourth centuries.82 Nonetheless, comparative use of the archaeological record suggests Athens and the Attic plains were as least as heavily populated in the seventh and sixth centuries as other regions of Greece; and despite regional variations, overall trends in settlement and land use are reasonably consistent across southern Greece on the basis of survey evidence. Generally, it is fair to say, between the eighth and sixth centuries settlement sizes gradually increased along with the general level of material prosperity, but were not yet at the high level attained in the fifth and fourth centuries.

A brief overview of areas bordering Attica and the Saronic Gulf, where intensive archaeological survey has been carried out, indicates some interesting general patterns (see Figure 10.1 and Table 10.1). Elsewhere in Greece, Archaic activity is best documented on nucleated ‘village’ or ‘city’ sites not scattered throughout the countryside. So, for example, in the southern Argolid, after a rise in site numbers in the eighth century, the seventh and sixth centuries witness a consolidation of primary site centres and second-order (village/hamlet) sites. There is no evidence for dramatic changes in cultivation practices and most sites seem to be situated near the areas of best agricultural land. Nor is there evidence for the plethora of small isolated rural ‘farmstead’ sites which characterise some later periods (notably the Classical and Late Roman).83

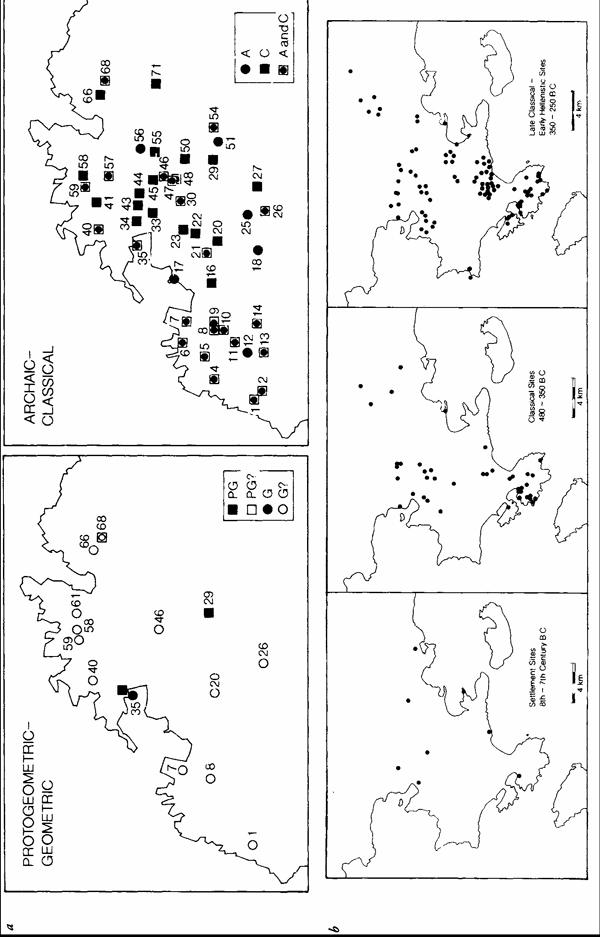

Figure 10.1 Site densities and distribution in a Kea, the b S. Argolid and c Methana between the Early Iron Age and the Early Hellenistic periods

Figure 10.1 Site densities and distribution in a Kea, the b S. Argolid and c Methana between the Early Iron Age and the Early Hellenistic periods

In Kea, the real boom in the exploitation of the countryside seems to come in the sixth century, though not at as high a level as in the Classical period. There is little evidence of expansion into the countryside in the eighth or seventh century.84

On Methana, Geometric and Archaic settlement is centred largely on the polis and two ‘village’ sites. The pattern of dispersed small ‘farmsteads’ exploiting the upland sector of the peninsula belongs to the Classical period (and the Late Roman, but that is another story).85

Finally, in Boeotia, the same general trend is evident. On the urban sites surveyed, the peak expansion was during the Classical period: Geometric and Archaic levels of occupation are much more restricted. This trend complements the evidence for the intensive exploitation and occupation of the countryside in the Classical period, notably during the fifth and fourth centuries.86

This pattern hardly suggests over-population or a landscape approaching its carrying capacity in the Archaic period. The assertions that this is a period of extensification into marginal agricultural lands, or Hanson’s elaboration, that farmers in Archaic and Classical times lived largely on isolated ‘homesteads’, receive little support from archaeological survey evidence.87 Rather, such extensification seems to start no earlier than the late sixth century, and is more generally a fifth- and fourth-century phenomenon across Greece, obviously with local, regional variations, but dating to roughly the same time as the Classical literary sources which postulate an Archaic period agrarian crisis. The evidence of survey suggests anything but an overcrowded countryside in the Archaic period. There is little Archaic evidence in Attica or elsewhere for the small isolated rural sites which characterise the more densely populated and intensively farmed countrysides of Classical Greece.88

Such an assessment does not tally with the bleak picture of Attic agriculture generally presented. Looking closely at the landscape of Greece as it might have been farmed in the seventh and sixth centuries, the available archaeological evidence suggests that the basic techniques of cultivation and the core crop plants were fully established in Greek agricultural systems in the Bronze Age and, I have argued elsewhere, continued in use throughout the Dark Ages and into the Archaic period.89 This does not mean there were no changes in farming systems and practices, nor that crops were not grown in different ways at different times by different farmers. But the fundamental repertoire of crops and techniques available to farmers in the Late Bronze Age was also there in the eighth century and the sixth century and the fourth century, and many variations and combinations were possible. Farming systems are highly flexible and resilient, and very sensitive to changes in the sociopolitical(and economic environments.

It is unnecessary to postulate some kind of large-scale agricultural or economic catastrophe,90 or to seek recourse to major innovations in technologies or crops91 to explain the agrarian conditions and the political history of Archaic Greece.

Over the course of the Archaic period, we see wealth increasing throughout Greece, despite local hiccups. I would guess that in Athens by the early sixth century not only were the wealthy wealthier, but more people might have had a claim to taking turns at power on the basis of newly acquired wealth (however that wealth was acquired)—others have certainly suggested this.92 These processes might have germinated the seeds of discontent which we find in Solon’s poetry.

The archaeological evidence suggests farmland was not under pressure in any absolute sense during the Archaic period, but relationships to land are mediated by social and political systems. Land was always the primary means of production in classical antiquity, but the social and political channels of access to it were frequently disputed. Whatever the terms of those disputes in early Athens, the cause was not overpopulation, exhausted soils, deforestation, a transition from pastoralism to arable agriculture, or the introduction of arboriculture. In any case, as Gallant has asked,93 if the land was depleted in the seventh century, how did it support later, higher levels of population and farming?

The question of land tenure raises interesting issues which cannot be fully resolved. But there is no a priori reason for asserting the primacy of some kind of ‘communal’ ownership of land over private land ownership of individuals within families, except that evolutionary logic has suggested that it ‘ought’ to be the case. In fact, most of the available evidence suggests that some notion of private property was at the heart of Greek concepts of land tenure well back into the dim and distant past—but how far back is anybody’s guess.94 Homeric kings and heroes seem to think they own their land and can pass it on to their offspring,95 in ways which would have been comprehensible to Classical Greeks. Hesiod’s Works and Days focuses on a dispute over land ownership which plainly concerns ‘private’, heritable land.

In the mixed agricultural regimes of southern Greece dry-farmed cereals and legumes, a range of permanent tree crops, and animal husbandry have been bound together and set within a diverse landscape in varying combinations since the Early Bronze Age. The notion of private, heritable tenure, especially for land permanently planted in trees, is perhaps a logical outcome, especially in tandem with a bilateral kinship system. This does not mean that systems of land tenure do not vary over the course of Greek history, nor that private tenure always means the same set of relationships to a piece of property, nor that all land has the same status vis-à-vis individuals and communities in any particular period (let alone over time). Perhaps we should not be looking for ‘the emergence’ of private land tenure in Archaic Greece, because it was always there as a fundamental principle in some form or other. Certainly there is nothing in Greece comparable to the shifting cultivation systems of Africa and the South Pacific, under which notions of the community as a whole ‘owning’ the land fulfil the logic of agrarian regimes where individuals and households do not permanently occupy or work the same plots for a lifetime, nor pass the right of permanent tenure on to their children.

So what is the problem for Solon’s Athens? My guess is that ‘privately owned’ land (whatever that meant at the time, and however one acquired the right to ‘own’) was essential for partaking in the polis and sharing in its power (however exactly political processes operated). In other words, membership of the elite group which constituted the state was synonymous with the land-holding group. Those outside this circle, at any socio-economic level, gained access to land only through them, via the dependency relationships for which so much confused evidence abounds in the classical sources (the hektemoroi and all that).

If I am right, the tele and the ‘land reforms’ may well represent a formalisation of access to land for those with sufficient wealth, circumventing any dependency relationships. This need not entail the ‘democratisation’ of land-holding to any significant extent, though a broadening of the land-holding base has generally been assumed.96 The name of the top class unquestionably implies the possession of agricultural produce (and therefore access to the primary means of production and labour), and the rest of the quantitative qualifications passed on to us, and perhaps invented, by later writers do as well.97 Does this then mean that partaking in the polls and its power structures was entangled with land ownership from the start? I think they were. It may be that the thetes who counted as part of the polis, at least at the beginning of the system, were those with at least some land: the landless citizen may well be a later development (he did not exist at all in the cities where there was always a land-owning qualification for citizenship).

THE SOLONIAN TELE: A VIEW FROM THE TOP

Finally, I will examine the economic implications of the Solonian property classes: an exercise also attempted by others.98 In fact, Starr’s calculations are not wildly different from mine, though I think mine have a stronger basis:99 the information and assumptions Starr was using were old and flawed even when he was writing.100 However crude the figures, this exercise puts the quantitative assessment of the tele in an interesting perspective, and highlights implications which the evaluations of Starr’s figures have not explored.

In Table 10.2 the figures given by Aristotle and Plutarch for the different assessment levels of the tele have been converted into grain equivalents. The question of how the quantitative assessments actually operated either in theArchaic period or later has been much debated: the arguments are nicely summarised by Rhodes,101 and his conclusion has been generally accepted102 that no one normally bothered to measure produce, but households classed themselves in an atmosphere of competitive peer pressure, so that measurement might take place if status were challenged.

Table 10.2 Property requirements and subsistence potential of the Solonian property classes

It is very likely that the tele might have been based originally on straightforward grain measures. Cereals were the major staple in all periods and how much a household produced and/or stored would probably be the most obvious reliable indicator of their wealth and standing in a non-monetary economy. The notion of ‘wet and dry measures’ mentioned in Aristotle,103 like other elaborations of and speculations on the system in later writers and lexica, might perhaps be either a confusion or a later development.104 The name of the pentakosiomedimnoi suggests grain was intended as the measure or standard.105 It may well be that the numbers associated with the three bottom classes were inventions of Classical times, extrapolated from the name pentakosiomedimnoi (see note 97). Even if that is right, the number 500 is embedded in the name, which seems to be genuinely Archaic. Moreover, it must certainly refer to dry weight, for which medimnoi were always reserved. In ancient Greece wine and oil were never measured in medimnoi, but in liquid measures (choai, amphorai).

Land areas are difficult to determine from production figures, since productivity is highly variable both inter-annually and in different locations (they probably did not think in terms of land areas anyway). Hence the use of a high productivity figure per hectare in Table 10.2: the aim is to determine near-minimum land holdings, since the use of a lower productivity figure would suggest larger holdings of land.

What emerges strikingly is that the top three classes must have been very wealthy indeed, if these are the levels to which they produced and stored cereals in most years.106 These figures also suggest that they not only have good land available, but also that they could mobilise the labour to work it. Such households would have been rich even in Classical Greece. Even after Solon’s reforms, office holding, restricted to the top two classes for the most part, must still have been limited to a very narrow elite. What the formalisation of the tele must have achieved was to fix rules for belonging to that elite, perhaps along new lines. That the system was in any sense ‘egalitarian’, or that it allowed those at the bottom greater access to land and power, I think must be highly questionable.

So, if, as is generally accepted, hoplites were from the zeugite telos,107 we are hardly seeing a broadly based military force composed of sturdy yeoman peasants or free farmers. Whatever hoplites became by the middle of the fifth century, in this period they were something different. The most likely possibility is that they were wealthy in relative terms in comparison with their socio-economic position in the fifth century.108 If the name refers to the ownership of a yoke of cows or oxen, this would suggest that the category covers comfortable, rather than poor farmers: draft animals were expensive to own and maintain even in Classical times.109 Another possibility is that in some circumstances their armour was supplied by another party in this early period.

And what of the thetes? The most striking thing is that, at least in this early period, this telos must have covered most of the population. Is this what Solon meant by the demos in his poetry?110 If so, then a goodly chunk of the demos may have been ‘poor’ only in relative terms, and their poverty was very much a perspective from the top looking downward. Clearly the thetes must have included everyone from those with a tiny scrap of garden to substantial kulak-like landholders, and the odd hoplite. To show these are not unrealistic numbers pulled out of thin air, I have included figures (in Table 10.2) on the subsistence production of wheat on Methana in the 1970s. Methana farmers produce much more than just wheat on their average holdings of 3.5 ha: this includes the land used for other arable crops, fallow and trees. If they grew barley, productivity would be even higher: they have the luxury of being able to grow all wheat because of the use of chemical inputs. Though Methana has good moisture-retentive soils, the peninsula, on the western side of the Saronic Gulf, has rainfall as low as Attica and is much steeper. Productivity on average to good land in Attica would be at least as high as on Methana, and it is largely this better land which was farmed during the Archaic period. A modern Methana household would be somewhere near the bottom of thetes, on the basis of the figures which have come down to us.

The tele, then, offer a view of the Athenian polis conceived from the top. Whether the full range of numerical assessments is genuinely Archaic, or a later invention, does not alter the fact that some kind of measured ‘yard-stick’ for membership related to food production, probably grain, is embedded in the very name of the top class. The amount highlights the considerable agrarian wealth of this group even by Classical or modern Greek standards. The Solonian ‘system’ most probably reflects the contests for access to power within a very small elite, entangled with the contest for access to land, and perhaps also the ability to mobilise labour. Solon’s ‘mythical democracy’, as Mogens Hansen111 reminds us from the point of view of the fourth century, was a democracy of the lawcourt, the magistracies and the Areopagos, it was not ‘an assembly democracy in which power was exercised directly by the demos in the ekklesia’, like the fifth-century democracy of Perikles. And for those at the top, including Solon himself, the great heap of hoi polloi at the bottom was largely irrelevant.

NOTES

1 For example, Murray, Early Greece, 2nd edition, 184; Hansen, The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes, 296–300.

2 Rhodes, Commentary on the Aristotelian Athenaion Politeia, 142, 145–6; Hansen, op. cit. (n. 1), 88.

3 For a good summary see T.W.Gallant, BSA 77 (1982), 111–24.

4 Fabian, Time and the Other.

5 Start, The Economic and Social Growth of Early Greece, 161.

6 Starr, Individual and Community.

7 Snodgrass, Archaic Greece, 28.

8 T.E.Rihll, JHS 111 (1991), 114–15.

9 Manville, The Origins of Citizenship in Ancient Athens, 67.

10 For example, Murray, op. cit. (n. 1), 199–200; Woodhouse, Solon the Liberator, Forrest, The Emergence of Greek Democracy.

11 Forrest, op. cit. (n. 10), 150–1, 160–1, 168–74; Andrewes, The Greek Tyrants (hereafter=Andrewes, Tyrants), 85, and in CA.H., 2nd edition, iii.3, 387; Finley, Economy and Society in Ancient Greece, 162.

12 For example, Morris, Burial and Ancient Society, 3–8.

13 Ibid., 216.

14 Forrest, op. cit. (n. 10); Starr, op. cit. (nn. 5, 6); Snodgrass, op. cit. (n. 7), 91, 93–4; Hanson, The Other Greeks, 27, 45 and passim; cf. I.Morris, in Doukellis and Mendoni (eds) Structures rurales et sociétés antiques, 49–53.

15 Gallant, op. cit. (n. 3), categorised the work on Solon as formalist-Marxist, formalist-capitalist, substantivist: overlapping but not fully congruent categories. Hanson, op. cit. (n. 14), idiosyncratically modernising, goes against this general trend.

16 K.M. T.Chrimes, CR 46 (1932), 3.

17 Woodhouse, op. cit. (n. 10), 155–6.

18 Ibid., 83–4.

CQ19 A.French, CQ n.s. 6 (1956), 19–20.

20 Ibid., 20.

21 Andrewes, Tyrants, 84–9; CA.H., 2nd edition, (n. 11).

22 Forrest, op. cit. (n. 10), 150–64, 168–74.

23 Starr, op. cit. (n. 5), 180–6; Starr, op. cit. (n. 6), 77–9.

24 Andrewes, Tyrants, 87–9, CA.H., 2nd edition, (n. 11), 384–8; Forrest, op. cit. (n. 10), 161–3, 168–70; Starr, op. cit. (n. 6), 78–9; Starr, op. cit. (n. 5), 185; more recently restated by Murray, op. cit. (n. 1), 194–5 and Hanson, op. cit. (n. 14), 111–12, 122–5, who also takes a traditional line on the ‘agrarian crisis’ of Solon’s time, but sees the tele as benefiting ‘successful mesoi’ who were ‘middling farmers’, 123–4.

25 Finley, op. cit. (n. 11), 62–3, 76, 156–60; The Use and Abuse of History.

26 Finley, op. cit. (n. 11), 160; similarly see on the evolutionary development of the alienability of land, Finley, op. cit. (n. 25), 158–9.

27 For example, Finley, op. cit. (n. 25), 161 cites Apa Tanis, ‘who live in a secluded valley in the eastern Himalayas, untouched by European administrative intervention when they were first studied in 1944 and 1945’.

28 Finley, op. cit. (n. 11), 162.

29 Snodgrass, op. cit. (n. 7), 124–5; Gallant, op. cit. (n. 3); Morris, op. cit. (n. 12), 216; Morris, op. cit. (n. 14); Rihll, op. cit (n. 8); Manville, op. cit. (n. 9); Hanson, op. cit. (n. 14), xi.

30 Murray, op. cit. (n. 1), 191–2, and see, most recently, Hanson, op. cit. (n. 14), 82–5 and passim.

31 Hanson, op. cit. (n. 14), presents the most recent recycling of Snodgrass’s ideas, see also Morris, op. cit. (n. 12); Manville, op. cit. (n.

9), 89–92; Foxhall, BSA 90 (1995), 239–50. For Snodgrass’s most recent views, see his paper in Hansen (ed.) The Ancient Greek

City-State,30–40.

32 Even Starr, op. cit. (n. 6), 42–6, by 1985 felt the need to incorporate ‘anthropological models’.

33 Gallant, op. cit. (n. 3).

34 Ibid., 122–3.

35 Ibid, 124.

36 Ibid, 119–rank/order cultures driven by reciprocity.

37 Rihll, op. cit. (n. 8), 105 and n. 23.

38 Ibid, (n. 8), 104–10.

39 Manville, op. cit. (n. 9).

40 Ibid, 121.

41 Ibid, 89–92, 119–20, 122.

42 Ibid, 96–105.

43 Ibid, 112.

44 Ibid., 108–11; for an earlier version of the argument see N.G. L.Hammond, JHS 81 (1961), 76–98.

45 Manville, op. cit. (n. 9) 109–10, 119, 123, 129.

46 Ibid., 119.

47 Ibid., 123.

48 Ibid., 144–6.

49 Ibid., 119 n. 81.

50 Hanson, op. cit. (n. 14), 7–8, 108–12, 126.

51 Ibid., 112, 123.

52 Ibid., 28–9, 32–3, 36–40, 113–14.

53 Ibid., 49, 52–5, 96–7.

54 Ibid., 40–1, 79–85.

55 Ibid., 41–2, 78–9, 123.

56 There were global systems, but unlike modern ones, they were not dominated by powerful nation-states: cf. Champion (ed.) Centre and Periphery; Rowlands, Larsen and Kristiansen (eds) Centre and Periphery in the Ancient World.

57 Although establishing a fixed threshold between ‘states’ and ‘non-states’, and the existence (or not) of a ‘state’ is probably not crucial for interpreting and understanding societies like those of Archaic Greece.

58 For Classical Greece the case of Perikles, repeatedly elected to the generalship, comes to mind. Even in highly institutionalised and formalised modern bureaucracies, whether governmental, industrial or whatever, there is a considerable amount of flexibility in how different individuals fill specific posts— more than we recognise most of the time.

59 Documented for Athens in the seventh century: R.Osborne, BSA 84 (1989), 297–322; Morris, op. cit. (n. 12); S.C.Humphreys, JHS 100 (1980), 96–126; cf. Lefkandi: Popham, Sackett and Themelis, Lefkandi, i; M.R.Popham, P.G. Calligas and L.H.Sackett, AR 35 (1988/9), 117–29.

60 Humphreys, op. cit. (n. 59), 105–10.

61 Meiggs and Lewis, 2.

62 A fifth-century copy, ibid., 6.

63 For similar discourses of elite power cf. M.Gilsenan’s work on the elite in the Lebanon from the Ottoman to the present, in Gellner and Waterbury (eds) Patrons and Clients in Mediterranean Societies, 167–83.

64 Solon, fr. 33 West. All translations of Solon’s poetry are mine.

65 Solon, fr. 36.20–2.

66 Solon, fr. 37.6–10. On this fragment see also Salmon and Mitchell, p. 68 with n. 73 above and p. 33 below.

67 For example, Forrest, op. cit. (n. 10), 168–74; Andrewes, Tyrants, 84, C.A.H., 2nd edition, (n. 11), 377; Starr, op. cit. (n. 5), 173–85; Murray, op. cit. (n. 1), 186–95.

68 See citations in n. 67, and Hanson, op. cit. (n. 14), 112, 123, 125, who argues that Solon was a man of middle rank working in the interests of ‘middling’ farmers.

69 Cf. Mitchell, pp. 137–47 below.

70 Solon, fr. 23, assuming it is correctly attributed to Solon; an identical couplet is preserved in the Theognidea, 1253–4.

71 Solon, fr. 5.1–2.

72 Id., fr. 6.

73 Id., fr. 36.1–2.

74 Id., fr. 37.1–3.

75 Id., fr. 24.

76 For example, Forrest, op. cit. (n. 10), 168–74; Starr, op. cit. (n. 5), 181–5.

77 Solon, fr. 36; and see Harris, pp. 104–7 above, and Stafford, p. 164 below.

78 Morris, op. cit. (n. 12); Osborne, op. cit. (n. 59), 299–303.

79 Osborne, op. cit. (n. 59); S.Morris, The Black and White Style.

80 Osborne, op. cit. (n. 59), 307–9.

81 From 19 to 11 according to ibid., 305–6 maps 3 and 4.

82 H.Lohmann, Jahrbuch Ruhr-Universität Bochum (1985), 74, in Wells (ed.) Agriculture in Ancient Greece, 29–57, and his Atene.

83 Jameson, Runnels and van Andel, A Greek Countryside, 372–7.

84 Cherry, Davis and Mantzourani, Landscape Archaeology as Long-Term History, 331–3, 339–40.

85 Mee and Forbes (eds) A Rough and Rocky Place.

86 J.Bintliff and A.Snodgrass, JFA 12 (1985), 123–61; Antiquity 62 (234) (1988), 57–71.

87 Gallant, op. cit. (n. 3); Manville, op. cit. (n. 9), 123. Hanson, op. cit. (n. 14), 52–4, attempts to use survey data to prove the ubiquity of isolated residence for farmers. However, he has not fully understood, first, that many of the small rural ‘farmstead’ sites which crop up in survey (and excavation) are occupied only for very short periods, sometimes with long gaps in occupation; second, that the vast majority are fifth- to fourth-century or Late Roman in date; and, finally, that there is no reason to assume that all were occupied simultaneously, indeed, there is every reason to think that only a relatively small proportion were inhabited at any given moment (in which case the absolute numbers of the rural population for most poleis was probably quite low). For more detailed analyses of these issues see Foxhall, Appendix 1 in Mee and Forbes, op. cit. (n. 83); T.Whitelaw, in Proceedings of the International Scientific Symposium: Kea—Kythnos.

88 Indeed, there is considerably more evidence for the exploitation of the Greek countryside in the Late Roman period than in the Archaic.

89 Foxhall, op. cit. (n. 31).

90 For example, French, op. cit. (n. 19); Starr, op. cit. (n. 5), 156–60; Forrest, op. cit. (n. 10), 151.

91 For example, Sallares, The Ecology of the Ancient Greek World, 406–8.

92 Cf. Forrest, op. cit. (n. 10), 154; Murray, op. cit. (n. 1), 192, on the basis of Fustel de Coulanges, The Ancient City; Hanson, op. cit (n. 14), 123, 125.

93 Gallant, op. cit. (n. 3), 116. Cf. Foxhall, in Shipley and Salmon (eds) Human Landscapes in Classical Antiquity, 44–67; Foxhall, op.

cit. (n. 31).94 Fustel de Coulanges argued this long ago albeit it via a rather skewed reading of the Classical textual sources and from a completely different political point of view from mine (op. cit. [n. 92], 251–7); Hanson’s agenda of ‘agrarianism’ also highlights private property as a core feature but dates the rise of private ownership to the eighth century: op. cit. (n. 14), 39–40.

95 For example, Alkinoos, Od. 7.105–33; Odysseus’ estate from his father, Laertes, 24.336–44, which he will pass on to his son Telemachos, 23.138–9.

96 Manville, op. cit. (n. 9), 145–6; Forrest, op. cit. (n. 10), 168–9; Murray, op. cit. (n. 1), 193–4; Andrewes, CA.H., 2nd edition, (n. 11), 382; Rihll, op. cit. (n. 8), 124–5; Hanson, op. cit. (n. 14), 114–19.

97 Arist. Ath. Pol. 7.3–4; Plut. Sol. 18.1–2; see also Rhodes, op. cit. (n. 2), 137–8. I am grateful to Robin Lane Fox for the suggestion that later writers extrapolated the quantitative qualifications for the bottom three classes from the name (pentakosiomedimnoi) of the top class.

98 Starr, op. cit. (n. 5), 154–6; cf. Murray, op. cit. (n. 1), 194.

99 L.Foxhall and H.A.Forbes, Chiron12 (1982), 41–90.

100 A.Jardé, Les Céréales dans l’antiquite grecque.

101 Rhodes, op. cit. (n. 2), 141–2.

102 For example, Manville, op. cit. (n. 9), 144–5 n. 53.

103 Arist. Ath. Pol 7.4.

104 Cf. Manville, op. cit. (n. 9), 144–5 n. 53; Rhodes, op. cit. (n. 2), 141.

105 Generally assumed to be one class which was added as part of ‘the Solonian reforms’, for example, Forrest, op. cit. (n. 10), 161; Manville, op. cit. (n. 9), 145 n. 54; cf. Andrewes, C.A.H., 2nd edition, (n. 11), 385.

106 Did criteria for the tele, or telos, if we are only talking about a one-class system, include stored cereals, if a household’s assessment were challenged? Cf. Rhodes, op. cit. (n. 2), 142.

107 For example, Andrewes, Tyrants, 88; Murray, op. cit. (n. 1), 194; Hanson, op. cit. (n. 14), 111–12.

108 This might be analogous to the way in which features of economic well-being such as house and car ownership have trickled down the class system since World War II, as standards of living have risen and western societies have become more prosperous overall. On this point, that zeugitai do not represent subsistence peasants, but comparatively well-off farmers, I am broadly in agreement with Hanson, loc. cit.

109 The derivation of the term has been much debated in the scholarly literature. That zeugites refers to the owner of a yoke (zeugos) of oxen is most generally accepted, but a popular alternative still upheld by Hanson, loc. cit., is that it was a military designation, referring to men ‘yoked together’ in the phalanx. See D.Whitehead, CQ n.s. 31 (1981), 282–6; and Raaflaub, p. 55 with p. 59 n. 31 above.

110 Forrest, op. cit. (n. 10), 168–74, and see above.

111 Hansen, op. cit. (n. 1), 299.