14

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF SANCTUARIES IN EARLY IRON AGE AND ARCHAIC ETHNE

A preliminary view1

Catherine Morgan

If it seems perverse to discuss ethnos sanctuaries in a volume devoted to the development of the polis in Archaic Greece, I beg two excuses. The first is that some of the richest bodies of sanctuary data from mainland Greece deserve centre stage. The extent of discoveries in a number of ethne, especially since the late 1970s, amply justifies a preliminary evaluation, risky as this is where excavation continues. To put this into perspective, in the three regions central to most discussions of early polis religion, Argos, Corinth and Athens, only the Athenian acropolis2 and the Argive Heraion3 have produced a range and volume of votives to compare with, for example, eighth-century Tegea, Pherai or even Kalapodi. In the Corinthia, one might expect the near-complete disappearance of grave offerings between 750 and 600 to release goods for dedication,4 yet the flow is meagre. Evidence from Isthmia is relatively slight before the construction of the first temple around the mid-seventh century,5 and while Perachora is richer in votives, the real escalation only begins in Early Protocorinthian and continues through the first half of the seventh century.6 In terms of architecture, two cult buildings at Asine date to the second half of the eighth century, but there is little else before the first temple of Apollo at Corinth (c. 680) followed by the temple of Poseidon at Isthmia.7 In these latter cases, the principal innovation is the use of cut stone, and although this implies refinement of technique, it is hardly revolutionary in a region where stone sarcophagi had been common for over fifty years.8 At Perachora, the eighth-century ‘temple’ of Hera Akraia may be an Early Helladic house, and it seems unwise to date the building described by Payne as the temple of Hera Limenia (but probably a hestiatorion) much before the end of the seventh century, since earlier seventh-century bases are re-used in its hearth. Instead, as Blanche Menadier has recently argued, a few, probably late seventh-century, architectural remains from the area of Payne’s third temple of Hera probably belong to the first cult building.9 Assessment of the eighth-century origins of mainland religious architecture thus draws increasingly on evidence from outside polis territory. This is not to imply an unduly negative view of polis evidence, merely to stress that, from the viewpoint of cult archaeology, the extent to which the polis continues to dominate analysis of the role of cult in the representation or creation of group identity is disappointing.

Second, and more seriously, the clarity with which distinctions between ethne and poleis are sometimes drawn may foster simplistic perceptions of the role of shrines within each. It is often noted that many sanctuaries become archaeologically visible from the eighth century onwards, supposedly coincident with the emergence of the polis.10 An increase in sanctuary numbers is indisputable, although one should not pass over earlier evidence, much of which comes from ethne, nor ignore the impact of previous practice upon eighth-century innovation.11 Nonetheless, in developing this link, emphasis has been placed on historical ties between poleis and their territories, with the implication that the gods of the political community are also tied to the spot.12 The developing social and political geography of the polis thus offers a direct lead into the material development of shrines. The observation that every sanctuary belonged to a community is unexceptionable; more problematic is the fact that the idea of community tends, implicitly or explicitly, to be conceived in polis terms as a community of citizens. If one couches this more broadly, in terms of the development of interest enactment through time, the results may be relevant to a wider range of political communities. The contribution made by polis-based studies is, of course, considerable, but it must be understood in a broader political context, recognising that ethnos data can also produce observations of general relevance.

At present, ethnos shrines of purely local significance most often appear in synthetic discussions of Greek cult during the Early Iron Age, receive little direct attention during the Archaic and early Classical heyday of the polls, and return to the fore only in the context of later Leagues. The major exceptions are inter-state shrines which attracted a variety of non-local interests via their roles as meeting grounds, landmarks etc., as well as serving local communities.13 The complex processes of evolution involved are not of primary concern here, however.14 More serious than the omission of ethnos data is the structuring of interpretative schemata from a polis viewpoint, which is at best one-dimensional, at worst distorting, since it creates bias and neutralises ethnos data as an independent control.

Very few scholars have considered early ethne as phenomena in their own right, let alone examined the role of religion within them. However, a summary of implicit and explicit impressions might run as follows: in its purest form the ethnos was the survival of the tribal system into historical times; a population scattered over a large and flexibly defined territory was united politically in customs and religion, normally governed by some periodic assembly, and worshipped a tribal deityat a common religious centre.15 There are two obvious difficulties here: first, this is a timeless abstraction, and second, as has long been recognised, the pure ethnos is just as elusive as the pure polis (neither ‘tribalism’ nor urbanisation are adequate indices). From the late fifth or fourth century onwards, certain ethnos shrines did host major regional gatherings; hence Polybius’ (5.7–8) description of Thermon as the acropolis of all Aetolia, an ideal location for meetings for cult, politics and trade. But to treat this as a constant or basic function is an assumption and a simplification. The processes by which federal organisations drew upon and manipulated earlier cult orderings are fascinating, but proper reconstruction of individual cases must rest upon close phase-by-phase study. To illustrate the difficulties involved, we may consider the development of the principal shrine at Pherai, on the border of the eastern Thessalian plain, northwest of Volos.

Figure 14.1 Early Iron Age Thessaly

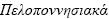

PHERAI

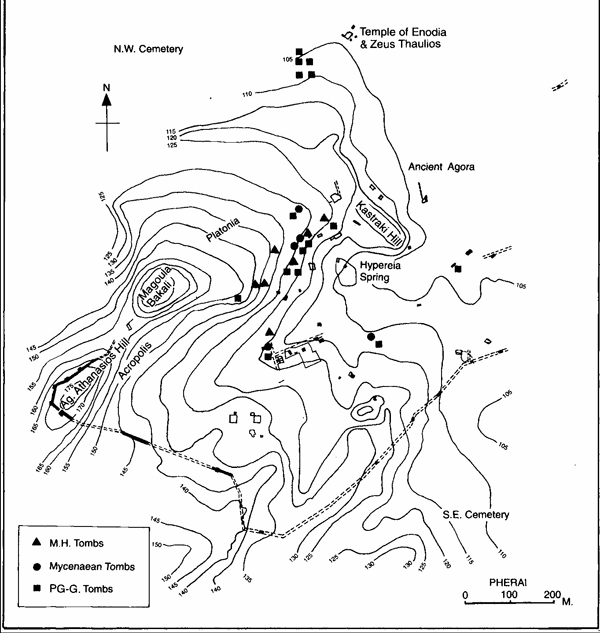

Ancient Pherai lies mostly under the modern town of Velestino, on an important junction of roads between Larisa, Pharsalos, Phthiotic Thebes and the Gulf of Pagasai (see Figure 14.1). Most public building dates from the fourth century onwards, but there is evidence of continuous settlement from Palaiolithic times. Among extensive traces of Early Iron Age activity (see Figure 14.2),16 the cemetery to attract most scholarly attention lies partially covered by the foundations of a monumental temple built c. 300 BC and probably dedicated to Enodia (a local deity later linked with Hekate and Demeter) and perhaps also Zeus Thaulios. This was not the first monumental temple; its foundations include elements of a late sixth-century structure, the site of which is unknown.17 Only forty cist inhumations contingent upon the temple were excavated, and much remains uninvestigated. Most graves contained few or no offerings, and despite later disturbance the impression of poverty is probably accurate.18 Of interest, however, is the placing of a shrine to a deity comparable to an Olympian (not a hero or ancestor), who came to share the temenos and perhaps the temple with Zeus, within a cemetery which may have had a tumulus still standing to mark the place.19 This is, however, highly appropriate for Enodia with her underworld connections. As her name suggests, she was also linked with roads, and in later times, the Thessalian practice of burying beside roads leading from settlements makes her attributes doubly appropriate. During the eighth century, however, Enodia’s cult was local to Pherai.20

Early votives, found redeposited in two favissae dug west and south of the temple during later cleaning operations, consist mainly of bronze and iron objects, mostly dating to the eighth and early seventh centuries, plus terracottas (largely female subjects) from the seventh century onwards.21 Setting aside material of uncertain provenance, Imma Kilian-Dirlmeier notes some 3,739 metal items as reasonably securely linked to cult. These include bracelets and rings plus bird and horse figurines, but almost half are fibulae,22 which imply concern with dress (since they largely replaced pins in Thessaly) and, given their use for fixing funerary clothing, may also have cult significance. The balance of items is echoed at Philia, the other major Thessalian eighth-century sanctuary, although with barely a third as many pieces over the same period, but the only other shrines to show the same pattern are distant Emborio and Lindos.23 At Pherai, therefore, a distinctive pattern may reflect cult needs. Similar bronzes occur in contemporary local cemeteries, but apart from a few rich, mainly child, burials, grave offerings are rare.24 There are thus symbolic links between the two contexts, reinforced by the character of Enodia, but an apparent bias in investment towards the shrine.25

Figure 14.2 Protogeometric and Geometric remains in Pherai (modern Velestino)

The shrine’s foundation date is controversial, but the most economical and widely accepted explanation remains primary deposition of votives somewhere within the earlier cemetery from c. 750 onwards. If the excavated sample of graves is representative, then unlike other city plots the cemetery may already have been abandoned for some 50–100 years (from c. 850–800, Thessalian Early Geometric). Allowing approximately 25–30 years per generation, this fits a three- to four-generation span of ancestral memory, and so the cemetery may have retained meaning for the living community. Were the unexcavated area to produce later graves, or the shrine to begin earlier, the association between cult and community ancestors would be yet more potent.26

Perhaps inevitably, given the quantity of votives and the later popularity of Enodia, the cult has been seen as holding pan-(Thessalian or even international significance from its inception. Certainly, by the fourth century Pherai was the centre of a cult attested across Thessaly, Macedon and beyond. Enodia appears on fourth-century, Pherai coin issues, for example, and was later worshipped at the altar of the Six Goddesses.27 Yet there is little to suggest that the earlier cult was of more than local significance,28 and its establishment is readily comprehensible in terms of regional settlement. Excavation and survey data from the southern part of the eastern Thessalian plain indicate activity at least from the eighth century onwards at the main city locations of later historical significance, and the spacing of these sites carries clear territorial implications (see Figure 14.3).29 This may, therefore, have been a time when reinforcement of local identity could appear advantageous; Arne (Philia) and perhaps Phthiotic Thebes30 also established or expanded their shrines at this time, and despite similarities in votives, local differences are strong. At the sanctuary of Athena Itonia at Philia, for example, evidence of sacrifice and dining and the sustained wealth of votives through the Archaic period contrast with the extant record of Pherai.31 The settlement structure within which these shrines operated remained largely unchanged until the fourth century, and until then significant developments concern fluctuations in investment between graves and shrines.

The idea that the quantity and variety of metalwork imply an international role from the outset is also untenable. Quantity alone is no argument: Geometric Pherai was a big town (Argos may be an appropriate comparison), but it is hardly sensible to match levels of dedication to population. More pertinently, Imma Kilian-Dirlmeier’s analysis of the style of eighth- and seventh-century metal votives shows that only 2 per cent are non-Thessalian, and of these half are Macedonian or Balkan (the remainder range from Italy to Egypt); the contrast with, for example, Olympia is striking.32 The presence of imports is predictable; they occur at most Greek shrines, however local, and finds at Pherai are readily explicable in terms of contacts along major neighbouring land routes or via Euboia. In the case of Thessalian votives, it is impossible to prove their precise origin or that of their dedicators; many fibulae probably came from a local workshop, perhaps linked to the shrine, but thisneed not imply a closely defined style or local clients.33 Their likely context is, however, suggestive. Allowing for post-depositional disturbance and the circumstances of excavation, there is no clear evidence for dining.34 The deposition of small objects, many linked with dress, perhaps around an altar among the graves of community ancestors, must therefore have formed a key act of worship. This would make a strange regional panegyri, and, if the shrine played a wider role, one would have to assume the acceptance of a distinctive practice across Thessaly, yet no other manifestation for over two hundred years.

Figure 14.3Theoretical territories of poleis on the eastern Thessalian plain

In short, the shrine of Enodia at Pherai was probably a local cult place belonging to a large and rich settlement, closely related in its material development to local needs and values. From the late fifth century, the spread of the cult through Thessaly and beyond reflects Pherai’s contemporary political role. It is, however, interesting that the two principal cults later to play a pan-Thessalian role, Enodia and Athena Itonia, are the earliest archaeologically attested, and it may be that perceived ‘tradition’ influenced their subsequent development. Clearly, Pherai’s development sits ill with simple characterisations of a tribal state and over-rigid distinctions between poleis and ethne. There are indeed points of contrast. Ethne rarely express identity via strong regional boundaries, for example, and evidence for sacral marking of state and local territory is often complex. In general, though, Greek state organisation reveals a spectrum of strategies through space and time; most ethne saw synoicisms, dioicisms, the politicisation of tribal or urban identities, and domination and subordination within regions and in relation to neighbours. One might therefore expect a complex of shifting personal and communal statuses to be reflected in group representation at an ideological level. Sanctuaries are logical places to look for this, yet in certain regions, such as Achaia, they played a relatively small role during our period,35 and the decision to enact aspects of personal and communal identity through cult is but one of a range of possible strategies. In order to trace this process of choice region by region, one must set cult alongside mortuary and settlement evidence, considering such traits as the nature and role of iconography and the disposition of artefact types and media, to assess shifts in the balance between contexts and their attendant interests. Here archaeology offers a level of contextual and chronological control rarely available in literary sources. In the case of Kalapodi in Phokis, for example, literary evidence dating back to the fifth century has been used to great effect by Pierre Ellinger,36 but in Arkadia, as in neighbouring Achaia, we are heavily reliant on Strabo and Pausanias, and although both are fully exploited by Madeleine Jost and Athanassios Rizakis respectively, with the late exception of Megalopolis, real time depth is lacking.37 Two contrasting case studies, Kalapodi and the regional cult system of Arkadia, illustrate the potential of this approach.

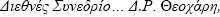

KALAPODI

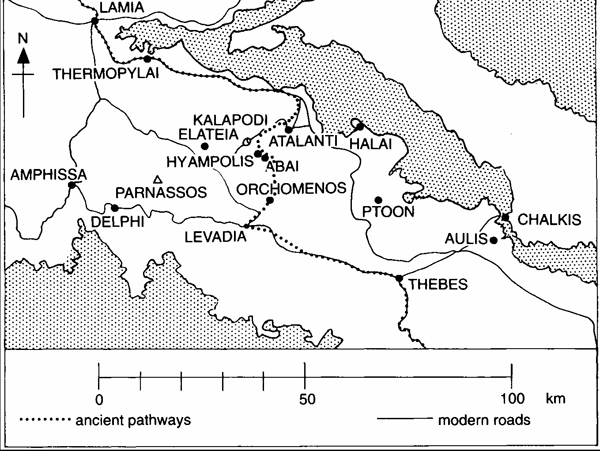

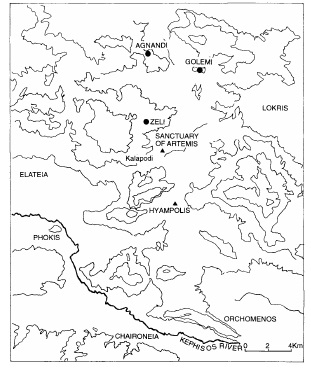

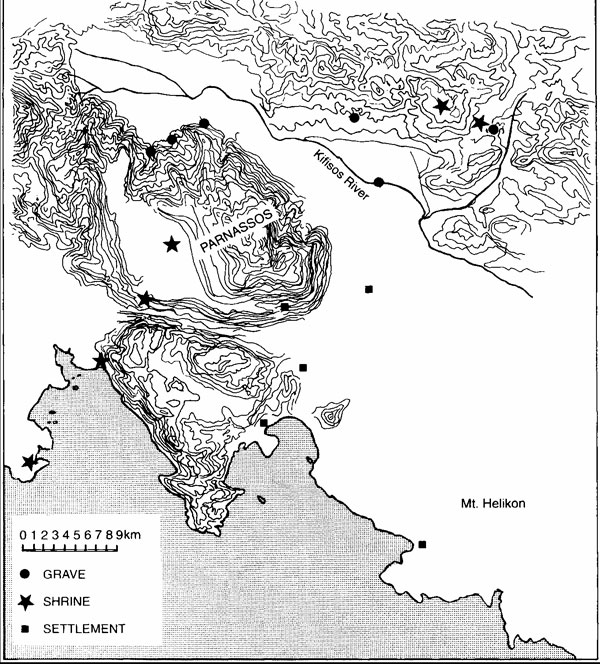

The sanctuary of Artemis at Kalapodi, the longest-lived of all mainland shrines, was founded in L.H.IIIC and continued into the fourth century AD. Strategically located on the border of Phokis and Lokris, it was controlled in Classical times by Hyampolis (see Figure 14.4).38 From later Archaic times onwards, the shrine’s pan-Phokian status was expressed in what isaptly dubbed the Phokian National Saga, recounting the often savage events of the Thessalian occupation of Phokis in Archaic times.39

Figure 14.4 The location of the sanctuary of Artemis at Kalapodi

In the Saga’s final act, the ‘Phokian despair’, the Phokians, faced with Thessalian threats to enslave their women and children and kill their men, threatened to burn their wealth (women and children included) on a vast pyre. Meanwhile, their men left to fight a final battle against the Thessalians at Kleonai near Hyampolis, their victory being marked by the celebration at Kalapodi of the Elaphebolia, the greatest festival of all Phokis. Archaeologically, evidence of Phokian domination of the shrine by the time of the Phokian League is plain,40 yet given Kalapodi’s marginal location, it is unclear whether this was always so, or whether it is even legitimate to speak of pan-Phokian interests before the sixth century, or of Kalapodi as a Phokian meeting place during the Early Iron Age. In order to explore these questions, it is necessary to work forward phase by phase through the shrine’s history.

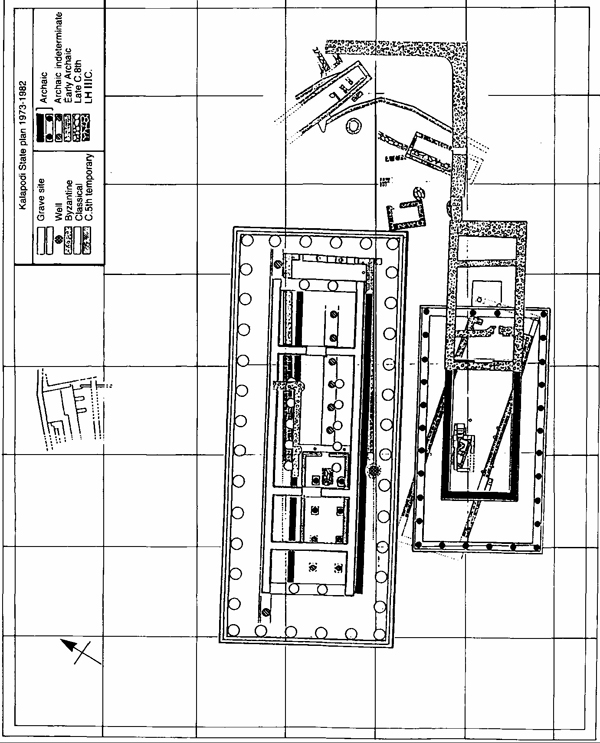

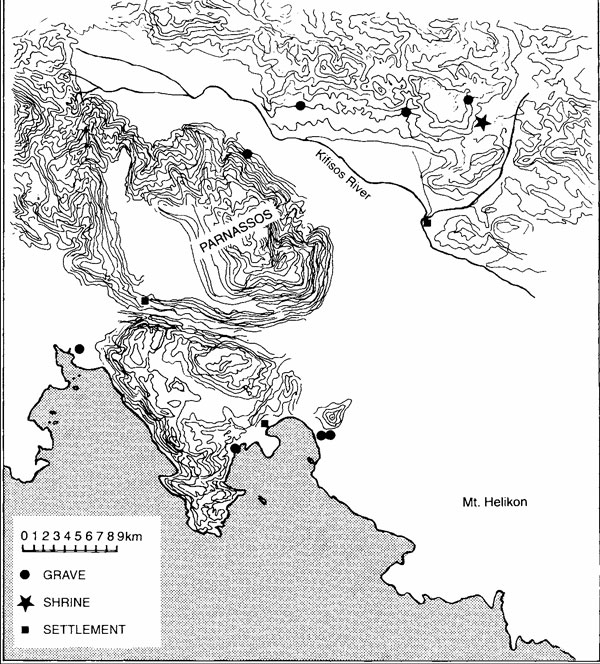

The first period of activity spans the life of the first altar, from L.H. IIIC Early until c. 950 (see Figure 14.5). Stratified deposits of sacrificial debris surrounding this altar contained votives (mainly seals, beads, and terracottas) and pottery, open shapes for drinking and dining, plus storage and cookwares, and miniatures. These deposits were dense and extensive from the beginning—the L.H. IIIC shrine probably covered some 400 square metres.41 The establishment of such a shrine at this time is comprehensible in terms of regional settlement. During L.H. IIIB, the surrounding area was densely inhabited, with, for example, numerous chamber tombs around the Exarchos valley.42 During L.H. IIIC, however, sites are fewer and are mostly extensive chamber tomb cemeteries (see Figure 14.6).43 These do, however, indicate that Kalapodi had a constituency on either side of the later Phokian border; and the presence of, for example, L.H. IIIC pictorial pottery may indicate links with Lokrian production centres (noting the rich collection discovered at Pyrgos).44 Furthermore, by contrast with the Peloponnese, the twelfth to tenth centuries in central Greece saw steady burial numbers and a peak in the wealth and diversity of offerings. Analysis of local cemeteries would allow comparison of the structure and manner of communal representation in burial and cult, but this must await the excavation of larger samples of extensive sites and the final publication of work in progress. At Elateia, for example, chamber tomb construction continued beyond Protogeometric times, with multiple burials of up to sixty individuals, perhaps in family tombs.45 Here classic Mycenaean-style chamber tombs with mass burials can be distinguished from smaller, less orthodox ones with one or two burials and poorer goods, but we cannot yet move beyond the obvious inferences. Certain comparisons can be made, however. Metalwork, for example, although present at Kalapodi, is concentrated in tombs; this bias affects the volume of material, especially weapons, and also the distribution of certain artefact types, such as extra-long ‘status’ pins, and is echoed in imported exotica such as scarabs.46

It therefore seems that when grave display was at its height, local communities within a restricted area set up a ritual meeting with sacrifice and dining. Noting the variety of grain types and quantity of pithos sherds present, Rainer Felsch suggested that the early celebration had an agricultural aspect,47 and the dominance of bulls among the figurine assemblage also implies economic interests and perhaps animal sacrifice.48 So far, the picture resembles that at other early shrines, notably the Amyklaion and Isthmia.49 Yet the focus on wild animals (especially deer) in the Kalapodi bone assemblage is lessusual than sheep, goat, or cattle. If deer relate to Artemis Elaphebolos, this may be a matter of cult.50 But especially as animal sacrifice also occurs at the Elateia cemetery, the cult itself may reflect local hunting practice, perhaps linked to status.51 In short, the local rationale for Kalapodi’s establishment is clear; central Phokis has as yet produced no contemporary evidence, and nothing in the early material record of southern Phokis indicates the existence of social or political ties with the north.52 Equally, the extent and nature of local cemetery continuity make it unlikely that the new shrine marked the arrival of newcomers.53

Figure 14.5 The sanctuary of Arternis at Kalapodi

A new phase of activity began c. 950 with the reorganisation of the shrine and the extension of the temenos. During the eighth century, two small mud-brick temples were built, one to the south by the previous cult centre, and one further north, on virgin soil, with a hearth altar which was to become a focus of future building.54 Among the votive assemblage, there was an increase in metal dedications, although the most dramatic escalation only began in the last quarter of the eighth century, when items such as arms and armour (paralleled in graves), tripods, and phalara became popular. Jewellery is most common, especially pins but also Thessalian fibulae; bronze figurines include bird pendants, horses, deer and lions appropriate to Artemis.55 From the second half of the eighth century there is also evidence of bronze-working on site, for the production of functional items, such as weapons, as well as votives.56 A further change concerns the bone assemblage, now dominated by sheep, goat and pig.57 The structure of the pottery assemblage remains the same; stylistically, Euboian connections are indicated by, for example, pendent semi-circle skyphoi, but eighth-century imports also include Cycladic and Early Protocorinthian wares.58

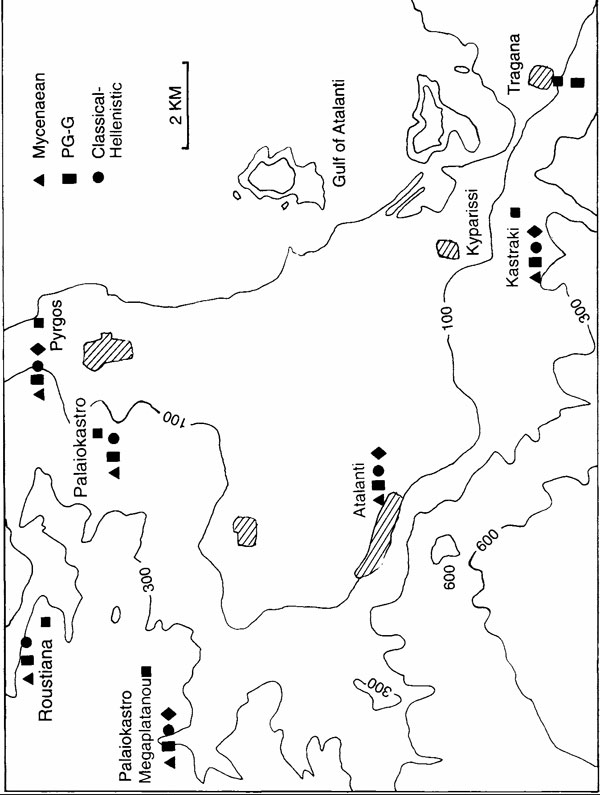

Equally striking are developments in the archaeology of the surrounding region. Later graves are found at or near a number of earlier cemeteries (Agnandi and Amphikleia, for example), but as yet, perhaps through a chance of excavation, only Elateiashows complete continuity.59 Here a few, tiny Geometric chamber tombs were built in the traditional way, and burials of all kinds continue into the early Classical period, but the focus of the Archaic and Classical cemetery probably lay elsewhere.60 Elsewhere in Phokis, Protogeometric and Early Geometric sites are few and widely spread (see Figure 14.7).61 In Lokris, activity now focused along the coast and on and around the Atalante plain, where cemeteries with a proportion of rich graves appear from Protogeometric onwards.62 The majority of acropoleis which continued into, or were occupied from, Archaic and Classical times are in this area, although many of the eight Lokrian cities mentioned in the Catalogue of Ships (Il. 2.531–3) remain to be found (see Figure 14.8).63 The attraction of connections with Euboia may have been important here, and this may also account for certain of the imports found at Kalapodi.

Figure 14.6 Principal sites in the vicinity of Kalapodi

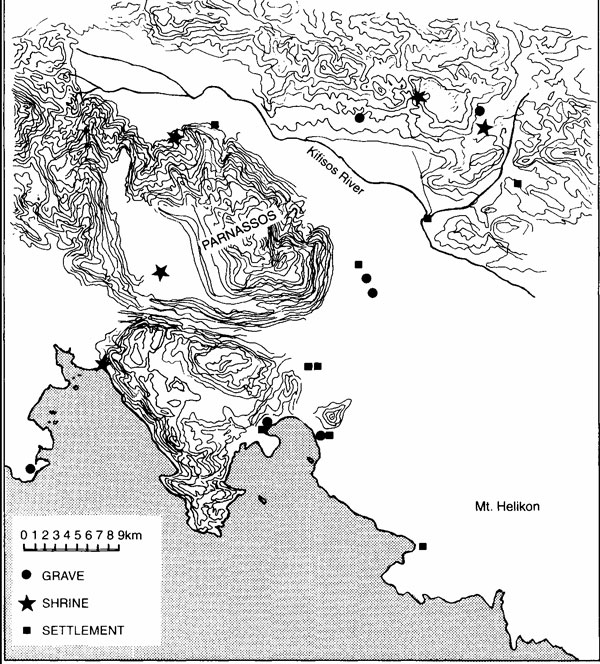

In Phokis, by contrast, slower settlement change may reflect more complex links between north and south; none the less, by the late eighth century a chain of sites extended to the south coast, and the basis of the Archaic city structure was established (see Figure 14.9a).64 Links between north and south are reflected in ceramic imports and in the balance of central and southern bronze styles at Kalapodi and in graves (e.g. at Amphikleia and Polydroso).65 This structure was consolidated through the Archaic period, and by the sixth century at latest is reflected in a network of shrines, notably at Elateia,66 Polydroso,67 Exarchos,68 Kirrha,69 the Corycaean Cave and Delphi,70 which vary in their physical appearance and patron deities.

In short, one can understand how, in terms of local Phokian and Lokrian settlement, Kalapodi could come to be perceived as a frontier shrine, especially when one considers possible Thessalian hostilities in Phokis, the main ‘event’ distinguishing the Archaic history of the two regions. Parallel strands in local myth-history may reflect aspects of this process. Strabo (424–5.9. 3.17) preserves a tradition whereby the settlement of east Lokris was attributed to Phokian expansion northwards from Elateia towards Daphnous. By contrast, the Lokrian king lists emphasise local (specifically Opountian) toponyms, and a border dispute between the Hyampolitans and their Lokrian neighbours is reported in scholia to the Iliad and Euripides’ Orestes.71

Figure 14.7 Protogeometric and Early Geometric settlement in Phokis

During the first half of the seventh century, Kalapodi underwent a major, probably Phokian-initiated, building programme. Two new temples and an outside altar were erected, and terracing provided a larger assembly area to the east.72 This was a substantial aggrandisement, although the dubious conjecture that it could not have been undertaken by Hyampolis alone is hardly evidence for a religious proto-league.73 The later Phokian League was intimately connected to independence from Thessaly, and as Ellinger argues, the ‘Despair’ bonfire, which symbolically incorporated the wealth of the nation, was central to its myth-charter. Equally striking, however, is the poverty of votives and the shortage of imports,74 which Ellinger tentatively relates to Thessalian occupation.75

Further expansion during the second quarter of the sixth century saw the construction of a still larger terrace plus two peripteral temples. Pottery imports reappear, but metal votives related to dress cease almost entirely, being replaced by weapons, body armour, and solid bronze rings.76 Felsch plausibly links these changes to the liberation of Phokis (dated, albeit controversially, around the time of the battle of Keressos c. 571), and the foundation of the Phokian League and the Elaphebolia.77 From this time onwards, Kalapodi’s place in Phokian history and national identity is clear, and materially, the shrine far outstrips the Phokikon, the physical centre and communal hearth of the Phokians (although limitations of excavation must be noted).78 There is, however, one footnote. Early in the fifth century Kalapodi was again ravaged by fire, perhaps by the Persians in 480 (Her. 8.32–3).79 After the Greek victory, a temporary cult structure with a hearth altar and a votive bench was built in the ruins of the north temple. Such was the desire for physical continuity that the Classical temple, begun in the mid-fifth century, physically entombed this building, which as a final act was burnt and the debris capped beneath the temple floor. Indeed, as the excavators note, some of the votives found in situ on the bench are types more common as grave offerings, effectively tributes to the entombed building.80 This is a remarkable sequence of events: continuity of altars is well attested in the Greek world, but the treatment of the temporary temple is exceptional.81

In summary, only relatively late in its history was Kalapodi adopted as the national, ancestral shrine of Phokis, stressing the liminal role of Artemis. It is possible to understand how and why the shrine was founded, to relate changes in votive offerings to circumstances in Phokis and Lokris, to see how a border might become meaningful through the eighth and seventh centuries, and to trace the politicisation of Phokian control from the seventh century. But this may only have been in place for a century at most before victory over the Thessalians fossilised the shrine in Phokian consciousness, and from this point we find a mania for continuity and tradition.82

Figure 14.8 Protogeometric and Early Geometric settlement in Lokris

In considering Kalapodi, I have chosen to set a single sanctuary within its regional context, and to consider how developments in group representation among its likely constituency fit those at the site itself. Here we have the advantage of the tongue durée, but Kalapodi is not unique in this respect, and comparable study of, for example, Isthmia, within the more stable ambit of Corinth, presents a different picture.83 A parallel approach, relevant where continuity is lacking, is to examine regional systems in terms of shrine location, votive practice and local differentiation. Here we may consider evidence from Arkadia.

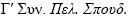

ARKADIA

By the fourth century at the latest, the Arkadian federation encompassed communities which, although distinct in their development and form, were in many cases explicitly described as poleis.84 Arkadian tribes are also attested,85 but although there is scant evidence for their political role during the Archaic period, it was probably not great. As Thomas Heine Niels en has shown, only in three minor cases do Classical historians report tribal affinities,86 and the majority of Roman attestations occur in Pausanias’ report (8.27.3–4) of the Arkadian Confederacy decree listing participants in the synoicism of Megalopolis. Major poleis such as Tegea usually stood alone as primary points of identification, and there is much to recommendthe view of Nielsen and Mauro Moggi that in Arkadia poleis did not develop within early tribal states but rather the reverse (a view which accords with the strong local focus of the archaeological record).87

Figure 14.9a Eighth-century settlement in Phokis

Shrines are particularly important contexts for material display in Arkadia, since by contrast with most other regions of Greece, Early Iron Age and Archaic graves are few.88 Although large cemeteries may remain undiscovered, burial customs probably did not emphasise material marking and formal burial of any sort may have been unfashionable. The main exception is Kynaithon, where burials around the Manesi and Kalavryta plains continue from the late eighth century into Classical times. But Azania was perceived as wild and remote, and as will be shown, connections with Achaia may be significant here.89

From the sixth century onwards, the material expression of cult across Arkadia appears increasingly uniform, with, for example, architectural emulation between temples, the assimilation of local deities to Olympians, and greater similarity in votives.90 Local identity could still be expressed within this framework; hence, for example, literary references to tombs of local heroes, such as Iphikles, brother of Herakles, at Pheneos (Paus. 8.14.9–10),91 self-consciously rustic symbolism (e.g. bronze shepherds from the shrine of Pan near Berekla),92 and unusual ritual, notoriously the human ‘sacrifice’ on Mt Lykaion, pushing the wild and unacceptable away from the civilised centre of Megalopolis.93 Yet this is very different from the material variation evident during the eighth and seventh centuries. Study of the nature and distribution of Arkadian shrines founded before 600 (on haphazard excavation evidence) permits us to look behind this regional pattern (see Figure 14.10).94

In Arkadia, relationships between town and chora vary greatly, and the evolution of complex ritual ties falls beyond our period. One should emphasise, however, that in a region mostly too high for easy wheat and olive cultivation and reliant on herding and barley and garden crops, and where cities often lay in close proximity to their neighbours, the variability of what constituted territory for particular purposes has rarely been considered.95 Thus Madeleine Jost has warned against simple distinctions between urban and rural shrines, highlighting instead geographical imperatives such as the avoidance of flood zones.96 Equally, since late Archaic and Classical Arkadian political rivalries were often constituted in terms of outside powers, it is worth considering the extent to which this may also be true of earlier sanctuary location, if only in the indirect sense of heightened self-awareness encouraging elaborate display combined with access to imported goods.

Figure 14.9b Archaic settlement in Phokis

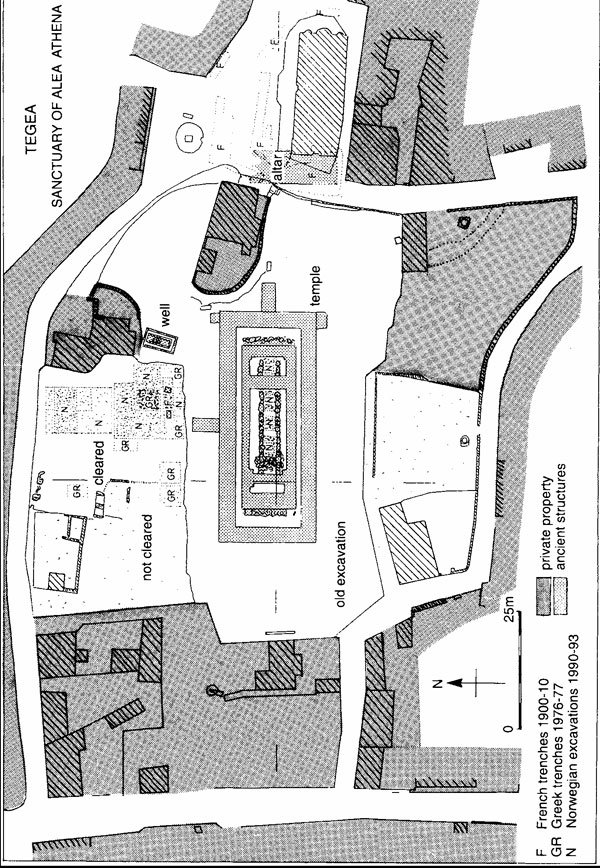

On present evidence, the earliest shrines appear in the north, south-east and south-west of Arkadia. To begin in the southeast,(the shrine of Alea at Tegea lies in the south of the Tegean plain, close to major routes into Lakonia and the Argolid.97 In Pausanias’ time (8.45.1), the local population was divided into nine demes. Tegean synoicism is usually dated between the end of the seventh and the mid-fifth century (Strabo [337.8.3.2] puts it c. 478–473),98 but most public building is fourth-century, including the city walls which probably encompassed the Temple of Alea, and there seems much to commend the view that the town annexed the shrine after synoicism.99

The early origins of the Alea cult were revealed by votives found in Charles Dugas’ excavations in the 1920s.100 More recently, the ‘first‘, late-seventh-century, temple has been shown to rest on the debris of a series of earlier structures (see Figure 14.11).101 Two successive buildings of the second half of the eighth century have been investigated, and further pestholes exist beneath them.102 In addition, there is evidence of unusually elaborate provision probably for the display of offerings.103 Sacrifice and dining are represented by burnt animal bone and a pottery assemblage focused on open shapes and pouring vessels,104 so some form of meeting seems to have been combined with dedication. Votives include pottery plus lead figures similar to those from the shrine of Artemis Orthia at Sparta, but small bronzes form by far the largest category. A massive range in a variety of local, Peloponnesian and central Greek styles is related iconographically to the cult and the interests of dedicators:105 animals (mainly horses and deer), humans, pendants (including some which may have served as seals, perhaps to mark goods passing though the shrine), jewellery, and an eclectic collection of miniatures, notably arms and armour (fewer and less realistic than the later hoplite equipment from Bassai, but an early representation of military interests).106 Since Geometric metalworking pits have been found in the area of the Classical temple pronaos, much may have been made in situ.107 Only monumental bronzes (especially tripods) are absent, and most terracotta figurines date from the late sixth or fifth centuries onwards, following the assimilation of Alea to Athena.108

Cult activity at Tegea dates back to the tenth century, but there was a major increase in the volume and range of dedications from c. 750.109 External pressure may have been a catalyst, but it cannot explain the richness of the votive symbolism or the long building tradition which must answer to local needs. More persuasive is a link between the late-seventh-century temple,110 the rise of Lakonia, and perhaps also Tegean synoicism. Certainly, the temple as local history store, containing thehide of the Calydonian boar, the Spartan fetters and Endoios’ sixth-century wooden cult statue (Paus. 8.46.1, 4, 8.47.2; Her. 1. 66.4), would make a more impressive statement than the small bronze votives which were by then slipping out of fashion.

Figure 14.10 Arkadia 800–600 BC

Slightly later is a shrine on the summit of Psili Korifi above modern Mavriki, which may be that of Artemis Knakeatis mentioned by Pausanias (8.53.11).111 The first temple here is sixth-century, but Late Geometric finds show close links with Alea and probably came from the same workshops.112 Historically, the shrine lay in one of the villages of synoicised Tegea, although its status when founded is unclear. Yet if Mavriki did belong to an independent community, it would be unique (the next evidence, a seated female statue probably from a Demeter shrine at Hagiorgitika, dates c. 630)113 and its votive record exceptionally restricted. It therefore seems that it should be related to Tegea, stressing its location by a major route of communication.

Since the plain of Mantineia and its acropolis (Gourtsouli) lie immediately north of Tegea within the same plain complex, it is perhaps not surprising to find evidence of a shrine here, again probably dedicated to Artemis.114 Unlike Tegea, however, where the Alea shrine was separate from the acropolis, here the Mycenaean acropolis (Ptolis) was adopted for cult after a long hiatus. Just as there is no evidence for settlement here thereafter, so no rural shrines have yet been found before the end of the Archaic period.115 The peak of dedications at Ptolis in the late sixth to mid-fifth century, including such offerings as unique large terracottapeplophoroi, coincides with the most likely (if disputed) date for the synoicism of Mantinea.116 Yet walling of the late eighth or early seventh century on the west slope belongs to the first of a series of five cult buildings,117 and early offerings include local pottery (stylistically distinct from that of Tegea), Archaic terracotta figurines and personal items, such as jewellery.118 Unfortunately, there is no evidence for the nature of cult practice. Theodora Karagiorga may be optimistic in referring to the aristocratic character of dedications before the formal foundation of the city, and the range ofinterests expressed may be more restricted than at Tegea, but as she stresses, this is no rustic shrine.119 So although there is a clear rationale for self-expression via cult at both Tegea and Mantineia, it varies in nature between the two communities.

Figure 14.11 The Sanctuary of Athena Alea at Tegea.

In northern Arkadia the picture differs again. Lousoi, in the Chelmos mountains, is best known for its Hellenistic settlement and sanctuary of Artemis Hemera.120 Here too, although the first temple dates around the end of the seventh century,121 bronze votives begin during Late Geometric, and most, as Ulrich Sinn and Mary Voyatzis have argued, are probably products of a local workshop.122 The range of Late Geometric and Archaic jewellery and figurines echoes that at Tegea, but styles vary and numbers are lower (although the site has been plundered). Local terracottas, mostly dating from the seventh century onwards, include distinctive subjects such as dance groups, which raise questions about the role of performance in local ritual.123 By contrast, Late Geometric and Archaic pottery is rare, and there is no direct evidence for ritual conduct.124

Why a shrine should have been established here at this date is problematic, especially as there is scant evidence of local settlement.125 The geography of the marginal territory of Azania and southern Achaia may, however, be significant, in terms of communications and expressions of communal identity. It is interesting to compare Lousoi with the Achaian roadside shrine, perhaps of Apollo and Artemis, established by c. 750 at Ano Mazaraki-Rakita beside the Meganeitas valley.126 Here an extensive votive deposit included granary models, imports like scarabs, and personal items like stamps, jewellery and weapons, reflecting a range of gender, economic, and status interests close to that at Tegea. The deposit also includes pottery, and a concentration on open vessels combined with burnt bone implies sacrifice and dining. This is no simple roadside altar; whether there was a local settlement is unclear, but links with sites to north and south are evident in the ceramic record.127 Most striking, however, is the temple, which may tentatively be dated to the second half of the eighth century,128 and which continued in use, with no radical alteration, until its destruction by earthquake and fire early in the fourth century. Thereafter activity continued until the third century AD, but if a temple was built elsewhere it remains to be found, and the pottery distribution indicates continuing activity beside the ruin.

The shrine’s primary link with Aigion is clear129, and its location, close to the southern border of this meros along a busy road, seems significant. This is, however, the only case of territorial use of cult in eighth- and seventh-century Achaia, an interesting absence in a region whose organisation into twelve mere might imply concern with internal divisions. The other possible early sanctuary, on the Aegira/Hyperesia acropolis, is quite different in appearance and at least until the construction of Temple B, c. 650, less securely identified as a shrine.130 Within Aigion itself, no evidence of cult pre-dates an inscription on a bronze oinochoe of c. 450–440 which may refer to a local hero.131

Ano Mazaraki lies north of two flanking and politically distinct zones, the Pharai Valley in Achaia, and the plains of Manesi and Kalavryta in Arkadian Kynaitha; to the south lies Lousoi, and the area is cut by main roads. That its temple shows such continuity and conservatism through a period of expansion at Aigion and probably synoicism too, surely reflects particular concerns surrounding marginal territory. The archaeological records of these intervening zones contrast markedly; indeed, the environmentally circumscribed conditions of inland valleys are liable to produce extreme responses in terms of integration or demarcation of local identities. In the Pharai valley, the form and contents of eighth-century burials, and the grouping strategies employed, are highly eclectic. Of all areas of Achaia, the marking of local identities in burial is most complex here, and the sharpest discontinuities in the quantity and form of material evidence occur here also, since Archaic and Classical evidence is very slight indeed. It is possible that the synoicism of Pharai happened early, but further exploration is required to test this idea. By contrast, scattered burials are found on the plains around Manesi and Kalavryta from c. 700 onwards, some, like the renowned Ag. Konstantinos panoply burial, rich in offerings. Clearly, these two systems constitute a marginal zone for materially different groups. In such an area identity could matter greatly, and the coincidence of the establishment of the Lousoi shrine and the Kalavryta-Manesi burials is suggestive. In time, Lousoi acquired a range of functions (pasturing flocks from Chelmos, for example),133 but we cannot tell when these originated.

In south-west Arkadia, votives at the sanctuary of Apollo at Bassai, by contrast, date from c. 700 onwards, but increase in quantity only from c. 650. At this time, local and Elean pottery appears, and the first temple dates to the late sixth or early fifth century.134 In its early years at least, the shrine appears isolated, and as Nicholas Yalouris suggests, the predominance of lead and iron figures may reflect locally available materials.135 Miniature arms and armour are the most plentiful and iconographically significant bronze dedications, and whether one sees them as offerings by Cretans or by local mercenaries, they reflect the strongest single interest at any Arkadian shrine of this date.136 Elsewhere in Phigaleia, although Late Geometric pottery is found at Cretea on Mt Lykaion, most dedications here, as at the nearby altar of Zeus Lykaios and Pan, are seventh-century and later; the shrine of Pan at Berekla dates from the sixth century, as do the earliest offerings on Mt Lykosoura.137 Likewise, at the shrine of Athena in neighbouring Alipheira, an isolated hill site north-west of Andritsaina on the Triphylian border, a few small bronzes date to the late eighth century, but the majority are contemporary with the construction of the temple c. 550.138 The relatively late date of shrines in south-western Arkadia is striking, and it may be that a special interest served as a catalyst for their expansion if not establishment—mountain sites are favoured, for example, and the military interest at Bassai is notable.

As this brief survey shows, both the diversity of material expression and the geographical distribution of early shrines in Arkadia seem significant. All are in border areas of sorts, so may reflect external pressure, although at least at Tegea, the complexity of votive symbolism and early date of cult activity demand wider explanation. Given the limitations of excavation, negative argument is unwise; the lack of evidence in central Arkadia may, however, be significant. At present, the only early evidence, a unique eighth-century bronze group of masked dancers, comes from the probable shrine of Poseidon Hippios at Petrovouni; this may depict a ritual performance, and if, as Voyatzis suggests, the masks represent horses, a cult link seems likely.139 The next secure evidence comes from the late seventh- or early sixth-century shrine at Glanitsa in the chora of Tripolis, where the dominant iconography of shepherds and hunters echoes earlier observations about the expression of rusticity within the Arkadian sacral landscape.140 Clearly, there is no correlation between the existence or date of shrines, the presence of Geometric settlement, and the date of appearance of city ethnics.141 Equally, the majority of new seventh-century shrines cluster around the areas noted, but remain distinctive in form; Temple A at Pallantion, for example, is perhaps the strongest candidate for a bouleuterion temple on the Greek mainland.142 Only from the sixth century onwards can one trace the formation of a structured cult landscape encompassing the whole region.143

CONCLUSION

In summary, the manipulation of individual shrines and the evolution of regional cult systems are diverse processes, and the interests involved in shrine location and patterns of dedication complex. Nothing fits easily into simple models. Indeed, if, the most common trait is local idiosyncracy, this throws new light on the few cults, notably that of Demeter, characterised by greater material uniformity.144 It is often argued that the polis forged its identity through religion.145 Yet if poleis are perceived simply as basic unitary states, then, by comparison with ethne, one might expect their domestic religious organisation, and codes governing access between poleis (xenia) and between poleis and inter-state sanctuaries,146 to have been relatively simple. Ethne, by contrast, are multi-tiered, and their cult development fits complex processes of community and state evolution. Indeed, the evidence presented here runs directly contrary to the notion of the ethnos as Stammstadt.147 Clearly much more could be said; the role of shrines in synoicism varied greatly, for example, and the absence of certain cult forms is interesting. Thus the absence of ancestor cult has been cited as an argument against kinship as central to political structure in early ethne, but cults, as ideological statements, say less about the existence of aspects of structuring and identity than their politicisation, and in this respect, the absence of ancestor worship is less revealing than its presence in certain poleis.148 Above all, it is characteristic of ethne that the complex expressions of identity which they require are not necessarily made via cult alone or even primarily. Under such circumstances, we are forced to consider the complexity of the total ideological context and its evolution through time, issues equally relevant to the polis.149

NOTES

1 I am grateful to Peter Rhodes and Lynette Mitchell for their invitation to the Durham conference and for editorial assistance, to Blanche Menadier for helpful discussion, and to the British Academy for a Research Leave award which assisted my work on this topic. Detailed examination of the issues raised will appear in my book, Ethne: Early Greek States Beyond the Polis.

2 Notably bronzes: A.G.Bather, JHS 13 (1892–3), 232–71. C.Rolley, Fouilles de Delphes, v.3, 135 n. 7; E.Touloupa, AM 87 (1972), 57–76; Touloupa, in Buitron-Oliver (ed.) New Perspectives in Early Greek Art, 241–69.

3 Most recently, I.Strøm, Proc. Dan. Inst. Ath. 1 (1995), 37–127.

4 Dickey, ‘Corinthian Burial Customs, ca. 1100–500 B.C.’, 101–8.

5 E.R.Gebhard and F.P.Hemans, Hesperia 61 (1992), 9–22; Morgan, Isthmia, viii, forthcoming.

6 I.Kilian-Dirlmeier,  19 (1985–6), 369–75.

19 (1985–6), 369–75.

7 For an overview, see A.Mallwitz, AA (1981) 599–642. B.Wells, in  ii. 349–52.

ii. 349–52.

8 A.C.Brookes, Hesperia 50 (1981), 285–90; R.Rhodes, Hesperia 56 (1987), 229–32.

9 Hera Akraia: Payne et al., Perachora, i. 27–32, noting E.H. remains pp. 51–3; Menadier, ‘The Temple and Cult of Hera Akraia at Perachora’. Hera Limenia: Payne, op. cit. 110–15, 187; R.A.Tomlinson, BSA 72 (1977), 197–202; Menadier, op. cit., states fully the case for this chronology; Immerwahr, Attic Script, 16.

10 For example, A.Schachter, in Schachter (ed.) Le Sanctuaire grec, 8–10; Snodgrass, Archaic Greece, 33–4; de Polignac, Cults, Territory and the Origins of the Greek City-State, Chapter 1, and pp. 152–3 for summary.

11 C.A.Morgan, in Hellström and Alroth (eds) Religion and Power in the Ancient Greek World, 41–57.

12 For example, Alcock and Osborne (eds) Placing the Gods.

13 For example, Schachter, op. cit (n. 10).

14 Some are discussed in Morgan, Athletes and Oracles.

15 Snodgrass, op. cit. (n. 10), 42–4; Ehrenberg, The Greek State, 3–25; Daverio Rocchi, Città-stato e stati federali della Grecia classica, 107–12.

16 Di Salvatore, La città tessala di Fere in epoca classica; Béquignon, Récherches archéologiques à Phères de Thessalie; A.Dougleri Intzesiloglou, in  , 71–92; O.Apostolopoulou Kakavoyianni, in

, 71–92; O.Apostolopoulou Kakavoyianni, in  , 312–20.

, 312–20.

17 Béquignon, op. cit. (n. 16), 43–55 (attributing the temple to Zeus Thaulios); E. Østby, O.Ath. 19 (1992), 86–8. P.Chrysostomou, in

339–46.

339–46.

18 Béquignon, op. cit. (n. 16), 50–5; P.G.Kalligas, in  300 fig. 1.

300 fig. 1.

19 Béquignon, op. cit. (n. 16), 87–8, no. 52.

20 Chrysostomou,  (see, e.g., West Cemetery, 62–8); O.Apostolopoulou Kakavoyianni, in

(see, e.g., West Cemetery, 62–8); O.Apostolopoulou Kakavoyianni, in  57–70.

57–70.

21 Béquignon, op. cit. (n. 16), 57–74; Kilian, Fibeln in Thessalien, 6–8; Chrysostomou, op. cit. (n. 20), 29–61.

22 I.Kilian-Dirlmeier, JRGZ 32 (1985), 216–25.

23 Kilian, op. cit. (n. 21), 8–10, 168–9; and PZ 50 (1975), 105–6.

24 Apostolopoulou Kakavoyianni, op. cit. (n. 16), 313–17.

25 Two rich P.G. tholoi with multiple burials, north-east of Chloe near Velestino, may, however, reflect a pre-sanctuary pattern of investment. Alternatively, the practice of burying wealthy citizens beside roads leading out of town (and in a different grave-type) may have early origins. We cannot yet determine whether they were isolated cases: P.Arachoviti, in Èåóóáëßá, 125–38; Dougleri Intzesiloglou, op. cit. (n. 16), 78–9 n. 44; V.Adrymani Sismani, AAA 16 (1983), 23–42.

26 Vansina, in General History of Africa, i; Antonaccio, An Archaeology of Ancestors, 252–3.

27 Chrysostomou, op. cit. (n. 20), 29–75, part B section 2.1; Moustaka, Kulte und Mythen auf thessalischen Münzen, 30–6; S.G.Miller, CSCA 7 (1974), 231–56.

28 With the possible exception of a late Archaic/early Classical temple at Pharsalos (AD 19 [1964], â. 261; Chrysostomou, op. cit. [n. 17], 94–9), an inscribed stele of the third quarter of the fifth century from Larissa is the earliest attestation elsewhere: Chrysostomou, op. cit. (n. 17), 80–8; IG ix.2 575.

29 M. di Salvatore, in  93–124.

93–124.

30 Phthiotic Thebes: PAAH (1907), 166–9.

31 Philia: AD43 (1988), â. 256–7; 22 (1967), ß. 295–6; 20 (1965) P. 311–13; 19 (1964), â. 244–9; 18 (1963), â. 135–8; Kilian in Hägg (ed.) The Greek Renaissance of the Eighth Century B.C., 131–46; A.Pilali-Papasteriou and K.Papaeuthimiou, Anthropologika 4 (1983), 49–67. Athena Itonia: N.Papahatzis in  321–5; C.Bearzot, CISA 8 (1982), 43–60.

321–5; C.Bearzot, CISA 8 (1982), 43–60.

32 Kilian-Dirlmeier, op. cit. (n. 22), 216–25.

33 Chrysostomou, op. cit. (n. 17), 47 n. 44, suggests commercial exchange at the festival; K.Kilian, AKB 3 (1973), 431–5, offerings of transhumant pastoralists. Metalwork: Dougleri Intzesiloglou, op. cit. (n. 16), 78 fig. 8.

34 Béquignon, op. cit. (n. 16), 73–4; Kilian, op. cit. (n. 21), 186 notes Protocorinthian pottery.

35 Morgan and Hall, in Hansen (ed.) Introduction to an Inventory of Poleis, 164–232, for pre-Classical Achaia.

36 Ellinger, La Légende nationale phocidienne.

37 M.Jost, REA 75 (1973), 241–67; Jost, BCH 99 (1975), 339–40; Jost, Sanctuaires et cultes d’Arcadie; Jost, in Alcock and Osborne, op. cit. (n. 12), 217–30; Rizakis, Achaie, i.

38 R.C. S.Felsch, in Hägg and Marinatos (eds) Sanctuaries and Cults in the Aegean Bronze Age, 81–9; Felsch, in Hägg, op. cit. (n. 31), 123–9; Felsch, in Etienne and le Dinahet (eds) L’Espace sacrificiel dans les civilisations méditerranéennes de I’antiquite, 85–91; R.C. S. Felsch, H.J.Kienast and H.Schuler, AA (1980), 38–123; R.C. S.Felsch et al.,AA (1987), 1–99.

39 See Ellinger, op. cit. (n. 36), for discussion and analysis of the sources.

40 For example, in the coin assemblage: Ellinger, op. cit. (n. 36), 32, citing Felsch, personal communication.

41 Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 46–7; Felsch, op. cit. (n. 38, 1981); Felsch et al., op. cit. (n. 38), 3–5, 26–40.

42 Hope Simpson, Mycenaean Greece, 78–81; Felsch, op. cit. (n. 38, 1981), 81–2; Ph. Dasios,  4 (1992), 18–97; AD 34 (1979), â. 186.

4 (1992), 18–97; AD 34 (1979), â. 186.

43 In addition to reports in AD from 1970 onwards, see F.Dakoronia,  5 (1993), 25–39; Schachermeyr, Die ägäische

Frühzeit, iv. 319–22.

5 (1993), 25–39; Schachermeyr, Die ägäische

Frühzeit, iv. 319–22.

44 F.Dakoronia, in 2nd Symp. Ship-Construction, 117–22; Felsch et al, op. cit. (n. 38) figs 50, 51.

45 Dakoronia, op. cit. (n. 43).

46 F.Dakoronia, in  292–7; Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 54. Pottery styles belong with a common local tradition, but open shapes dominate at the shrine and closed in graves: Felsch et al., op. cit. (n. 38), figs 55, 56.

292–7; Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 54. Pottery styles belong with a common local tradition, but open shapes dominate at the shrine and closed in graves: Felsch et al., op. cit. (n. 38), figs 55, 56.

47 AR 29 (1982/3), 32.

48 Morgan, op. cit. (n. 5), ch. ii.4.

49 Demakopoulou,  Morgan, op. cit. (n. 11).

Morgan, op. cit. (n. 11).

50 Ellinger, op. cit. (n. 36), 27, 33.

51 Morris, in Hägg and Nordquist (eds) Celebrations of Death and Divinity in the Bronze Age Argolid, 149–55.

52 S.Müller, BCH 116 (1992), 445–96 on L.B.A. Delphi and environs (the relationship between S.M. and later finds is unclear); Vatin, Médéon de Phocide. Material similarities exist between Kalapodi and Delphi (e.g. Felsch, op. cit. [n. 38, 1981], 84), but are not strong.

53 Ellinger, op. cit. (n. 36), 34, 36–7, rightly doubts that Artemis’ link with frontiers and military victories was a Classical creation, but there is no reason to push it back this far at Kalapodi.

54 Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 47–63; Felsch et al, op. cit. (n. 38), 5–13.

55 Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 54–63; Felsch, op. cit. (n. 38, 1983); Felsch et al., op. cit. (n. 38), figs 13–14, 15–19.

56 Felsch, op. cit. (n. 38, 1983), 123–4; C.Risberg, in Linders and Alroth (eds) Economics of Cult in the Greek World, 36, 39–40. Cf. Philia: Kilian, in Hägg, op. cit. (n. 31).

57 Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 65.

58 Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 48 (comparing Lefkandi); Felsch et al., op. cit. (n. 38), 41–9.

59 Agandi: AD 25 (1970), â. 235–7. Amphikleia: Dasios, op. cit. (n. 42), site 12. Kalapodi area: AD 42 (1987), â. 234–5.

60 AD 29 (1973/4), â. 582–3; 34 (1979), â. 193–4; 43 (1988), â. 233; 36 (1981), â. 221–2; Paris, Elatée.

61 Dasios, op. cit. (n. 42), sites 51, 90, 100, 115 (site 66?); Vatin, op. cit. (n. 52), 59–68. Delphi: L.Lerat, 567/85 (1961), figs 40, 41; BCH 117 (1993), 619–31: secure settlement from the mid-tenth century onwards, twelfth- and eleventh-century sherds in lower layers.

62 For example, Tragana: A.Onasoglou, AD 36 (1981), a. 1–57; 41 (1986), â. 74; 38 (1983), â. 157; Fossey, The Ancient Topography of Opountian Lokris, 50–1. Atalante: AD 42 (1987), â. 226–8; F.Dakoronia, Hesperia 62 (1993), 119–20; Fossey op. cit., 68–74. Veryki Megaplatanou: AD 39 (1984), â. 135–6.

63 Megaplatonos: AD 36 (1981), â. 221; AD 33 (1978), â. 140; Dakoronia, op. cit. (n. 62), 123–4; Fossey, op. cit. (n. 62), 22–6, 33–5, 44–5, 62–5, 79–80. Kyparissi: AD 34 (1979), â. 187; 33 (1978), â. 139–40; C.Blegen, AJA 30 (1926), 401–4; Dakoronia, op. cit., 117–19; Dakoronia, Hesperia 59 (1990), 175–80. Halai: H.Goldman, Hesperia 9 (1940), 381–514; H.Goldman and F. Jones, Hesperia 11 (1942), 365–421; J.Coleman, Hesperia 61 (1992), 265–77; AD 42 (1987), â. 228–31. Catalogue of Ships: Dakoronia, op. cit. (n. 62).

64 See Dasios, op. cit. (n. 42).

65 Amphikleia: BCH 78 (1954), 132–3. Polydroso (Souvala): X. Arapogianni-Mazokopaki, AAA 15 (1982), 76–85.

66 Paris, op. cit. (n. 60), 73–118, 139–77, 257–98; for the dating of 286 no. 8 see Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 57.

67 AD 27 (1972), â. 384–8; P.G.Themelis, ASAA 61=n.s. 45 (1983), 227–8.

68 V.W.Yorke, JHS 16 (1896), 298–302; contra Philippson, Die griechischen Landschaften, i.2, 716–17; Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 39; Ellinger, op. cit. (n. 36), 25.

69 J. -M.Luce, in Bommelaer (ed.) Delphes, 263–75.

70 Antre corycien, i-ii.

Philologus71 W.Oldfather, Philologus 67 (1908), 411–72; Fossey, op. cit. (n. 62), 7; schol. Il. 2.517b (Erbse); Or. 1094 (Schwartz).

72 Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 63–7; Felsch et al, op. cit. (n. 38), 13–9; Felsch, op. cit. (n. 38, 1991), 86.

73 Ellinger, op. cit. (n. 36), 34.

74 Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 66; Felsch et al., op. cit. (n. 38), 54.

75 Ellinger, op. cit. (n. 36), 34.

76 Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 67–8, 78–83, 112–14; Felsch et al., op. cit. (n. 38), 19–25, 54–5.

77 Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 83–5; Ellinger, op. cit. (n. 36), 18–21.

78 E.French and E.Vanderpool, Hesperia 32 (1963), 213–25; P.Ellinger, in Felsch et al., op. cit. (n. 38), 98.

79 Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 84–5.

80 Ibid. (n. 38), 68–70, 85–99; Felsch, op. cit. (n. 38, 1991), 88–91.

81 See also Felsch, Kienast and Schuler, op. cit. (n. 38), 98–9.

82 A related issue is the impact of Delphi’s inter-regional role, culminating in the First Sacred War: Morgan, op. cit. (n. 14), ch.4.

83 Morgan, op. cit. (n. 5), Part III.

84 Federal interpretation of fifth-century Arkadikon issues: Williams, The Silver Coinage of the Phokians; Kraay, Archaic and Classical Greek Coins, 97–8; contra T. Heine Niels en, in Hansen, and Raaflaub (eds) More Studies in the Ancient Greek Polis, 39–61. Confederacy, e.g. Dušaniæ, The Arcadian League of the Fourth Century, J.Roy, Phoenix 26 (1972), 334–41.

85 J.Roy, A. Ant Hung. 20 (1972), 43–51.

86 T.Heine Nielsen, in Hansen (ed.) Introduction to an Inventory of Poleis, 117–63, especially 132–43.

87 M.Moggi, RFIC n.s. 119 (1991), 59–62.

88 AD 22 (1967), â. 217; 37 (1982), (â. 118; Holmberg, The Swedish Excavations at Asea in Arcadia, 112–13; S. and H.Hodkinson, BSA 76 (1981), 291–4; Jacobsthal, Greek Pins, 7–9.

89 I.A.Pikoulas, in  . ii. 269–81; M.Petropoulos, Horos 3 (1985), 63–73.

. ii. 269–81; M.Petropoulos, Horos 3 (1985), 63–73.

90 F.E.Winter, EMC 10 (1991), 193–220; E.Østby, in  . ii. 65–75; Jost, op. cit (n. 37, 1985), 368–70; Voyatzis, The Early Sanctuary of Athena Alea at Tegea, 239.

. ii. 65–75; Jost, op. cit (n. 37, 1985), 368–70; Voyatzis, The Early Sanctuary of Athena Alea at Tegea, 239.

91 Jost, op. cit. (n. 37, 1985), 534–40.

92 U.Hübinger, in Palagia and Coulson (eds) Sculpture from Arcadia and Laconia, 25–31; Jost, op. cit. (n. 37, 1975); W.Lamb, BSA 27 (1925/6), 133–48.

93 Cf. Burkert, Homo Necans, 84–93; Hughes, Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece, 96–107; Jost, op. cit. (n. 37, 1985), 258–67.

94 Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90).

95 Hodkinson and Hodkinson, op. cit. (n. 88); Fields, ‘The Anatomy of a Mercenary’, 52–6.

96 Jost, op. cit. (n. 37, 1994).

97 Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 10–20; Callmer, Studien zur Geschichte Arkadiens, 109–35.

98 Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 11 and n. 14; Moggi, I sinecismi interstatali greci, i. 131–9.

99 V.Bérard, BCH 16 (1892), 547–9; Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 12–13. Theatre: R. Vallois, BCH 50 (1926), 135–73. Agora: Pausanias 8. 49.1; Voyatzis, op. cit. (no. 90), 13–14; Jost, op. cit. (n. 37, 1985), 146–7 (if, as she speculates, Athena Polias’ was an open-air cult, it would contrast markedly with that of Alea). Gymnasium (at Palaio Episkopi): V. Bérard, BCH17 (1893), 16–23; Callmer, op. cit. (n. 97), 121. Pausanias (8.47.4) describes the stadium as close to the Alea temple. The citadel is not securely identified, although later votives come from the hill of Ag. Sostis: Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 16–17; Jost, op. cit. (n. 37, 1985), 154–6.

100 C.Dugas, BCH 45 (1921), 335–435; Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), passim.

101 E.Østby et al., O.Ath. 20 (1994), 98–107.

102 E.Østby, personal communication.

103 Østby et al., op. cit. (n. 101), 101, 111–12.

104 Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 62–84; Østby et al, op. cit. (n. 101), 99 n. 46, 101, 126–32.

105 Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), passim; Østby et at., op. cit. (n. 101), 117–32; M.E. Voyatzis, BSA 87 (1992), 259–79; Kilian-Dirlmeier, Anhänger in Griechenland, 40–1; Dugas, op. cit. (n. 100), 369–74 (votive loom-weights or amulets).

106 Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 198–202.

107 Østby et al., op. cit. (n. 101), 133.

108 Ibid. (n. 101), 117–19, 123; Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 239–42.

109 E.Østby, personal communication.

110 E.Østby, O.Ath. 16 (1986), 75–102.

111 Jost, op. cit. (n. 37, 1985), 159–61; Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 28–30.

112 Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 300–3, 305–7, 315, 317, 339.

113 Athens, N.M. 57; Jost, op. cit. (n. 37, 1985), 163.

114 T.Karagiorga Stathakopoulou, in  . ii. 97–115. Topography: Hodkinson and Hodkinson, op. cit. (n. 88).

. ii. 97–115. Topography: Hodkinson and Hodkinson, op. cit. (n. 88).

115 Karagiorga Stathakopoulou, op. cit. (n. 114), 108–9. Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 101 n. 177 (P.G. and G. from the chora). Archaic cult: Jost, op. cit. (n. 37, 1985), 132–4, 136; Fougères, Maritime et l’Arcadie orientate, 106; K.Lehmann, Hesperia 28 (1959), 153–61.

116 Karagiorga Stathakopoulou, op. cit. (n. 114), 107–8 figs 3, 4; Moggi, op. cit. (n. 98), 140–56 (c. 478–473).

117 Karagiorga Stathakopoulou, op. cit. (n. 114), 101–2, 104–5.

118 Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 87–9, 220–2; AD18 (1963), p. 89.

119 Karagiorga Stathakopoulou, op. cit. (n. 114), 107.

120 Reports of the Austrian Institute excavations appear in JOAI from 1981/2 onwards; W.Reichel and A.Wilhelm, JOAI 4 (1901), 1–89; Jost, op. cit. (n. 37, 1985), 46–51; Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 35–7.

121 Dating based on acroteria: Reichel and Wilhelm, op. cit. (n. 120), 61 fig. 128; Cooper, The Temple of Apollo at Bassai, 197–8.

122 U. Sinn, Jb. Ku. Samml. Bad.-Würt. 17 (1980), 25–40. Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 104–217 passim; cf. M.Weber, Städel-Jahrbuch I (1967), 7–18. The long-known Lousoi-Olympia group of animal figurines is often attributed to Olympia, but Lousoi may have been a centre: Heilmeyer, Frühe olympische Bronzefiguren, 99–109, especially 103; H.-V.Herrmann, JDAI 79 (1964), 22–4; cf. Zimmermann, Les Chevaux de bronze dans l’art géométrique grec, 91–113.

123 These also occur at Petrovouni and Olympia: Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 242–4; AD 18 (1963), â, pl.146a.

124 C.Schauer, in  forthcoming.

forthcoming.

125 Known Geometric sites probably lay in Kynaithan territory: Petropoulos, op. cit. (n. 89), 65–6.

126 M.Petropoulos, in  . ii. 81–96.

. ii. 81–96.

127 A.Gadolou, personal communication.

128 M.Petropoulos, in  . 141–58.

. 141–58.

129 See, for example, the distribution of impressed ware from Aigion: PAAH (1982), 187–8 pl. 125b; I. Dekoulakou, ASAA 60=n.s. 44 (1982), 230 figs 20–1; P.Amandry, BCH 68–9 (1944/5), 37 fig.3; M.Petropoulos, personal communication. (1982), 230 figs 20–1; P.Amandry, BCH 68–9 (1944/5), 37 fig.3; M.Petropoulos, personal communication.

130 For summary, S.Gogos, JOAI 57 (1986/7), 108–39; W.Alzinger, Klio 67 (1985), 394–426.

131 D.Robinson, AJA 46 (1942), 194–7.

132 For details, Morgan and Hall, op. cit. (n. 35).

133 U.Sinn, in Hägg (ed.) The Iconography of Greek Cult in the Archaic and Classical Periods, 177–87.

134 N.Yalouris, in Coldstream and Colledge (eds) Greece and Italy in the Classical World, 91–6; Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 125–6, 138– 9, 156–7, 201, 203, 206–7, 217, 244; N.Kelly, Hesperia 64 (1995), 227–77.

135 Ergon (1959), 109.

136 Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 218–20; A.M. Snodgrass, in Levi, Antichita cretesi… in onore di D.Levi, ii. 196–201; Jost, op. cit. (n. 37, 1985), 487–9; Cooper, op. cit. (n. 121), 17–28; N.Fields, in Sheedy (ed.) Archaeology in the Peloponnese, 101–12.

137 Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 43–4; cf. Jost, op. cit. (n. 37, 1985), 180–1, 185–7.

138 Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 37, 198, 201, 203–4, 207, 213; Orlandos,

139 Voyatzis, op. cit. (n. 90), 118 pl. 65.

140 Jost, op. cit. (n. 37, 1985), 217–19.

141 I.A.Pikoulas, Horos 4 (1986), 99–123; Pikoulas, Horos 8–9 (1990–1), 135–52; Heine Nielsen, op. cit. (n. 86).

142 Østby, op. cit. (n. 90); Østby, ASAA 68–9 (1990–91 [published 1995]), 109–18.

143 Noting here the potential role of Olympia as a broker between Arkadian communities: Morgan, op. cit. (n. 14), 79–85; Østby, op. cit. (n. 110), 93–102 (Arkadian architectural links with the temple of Hera).

144 S.G.Cole, in Alcock and Osborne, op. cit. (n. 12), 199–216.

145 C.Sourvinou-Inwood, in Marinatos and Hägg, Greek Sanctuaries, 11.

146 C.Sourvinou-Inwood, AION (archeol.) 10 (1988), 259–74; Sourvinou-Inwood, in Murray and Price (eds) The Greek City, 295–322. 147 F.Gschnitzer, WS68 (1955), 120–44.

147 F.Gschnitzer, WS68 (1955), 120–

148 Antonaccio, op. cit. (n. 26), 254.

149 For Athens, for example, see S.Houby-Nielsen, Acta Hyperboreia 4 (1992), 343–74; Houby-Nielsen, Proc. Dan. Inst. Ath. 1 (1995), 129–91; F. de Polignac, in Viviers and Verbanck-Pièrard (eds) Culture et cité.