CHAPTER 2

Conjuring Hysteria

Beliefs About Witchcraft in the 1600s

A witch, a witch…Goody Garlick is a double tongued woman. Because I spoke two or three words against her, now she is come to torment me. Did you not see her last night stand by the bedside, ready to pull me in pieces? She pricked me with pins. She pricked me with pins. She pricked me with pins.

—from the Records of the Town of East Hampton, 1658

Perhaps one of the saddest aspects of the witch panics that occurred in Connecticut, and elsewhere, is how they divided communities. Neighbors testified against neighbors. Children testified against parents. Husbands testified against wives and vice versa. This is well-illustrated in the case of Connecticut’s Elizabeth Garlick, who in 1658 was accused by her sixteen-year-old neighbor Betty Howell of being a “double tongued woman,” torturing her with pin pricks and sending a “black thing” to stand in the corner of Betty’s bedroom. When Betty died the next day, her family and neighbors blamed Goody Garlick.

Fifty-year-old Garlick must not have been popular in East Hampton, which today is part of Long Island, New York, but then was a part of the Connecticut Colony. Thirteen villagers testified at Goody Garlick’s indictment hearing, telling stories about her involvement with black cats, “threatening speeches,” a fat sow and piglets that died, an ox with a broken leg, a man who turned up dead and a child “taken away in a strange manner.” Neighbor Richard Stratton told judges he had heard another neighbor, Goody Davis, “say that [Goody Garlick’s own] child died strangely…and she thought it was bewitched, and she did not know of anyone…that could do it unless it were Goody Garlick herself.”

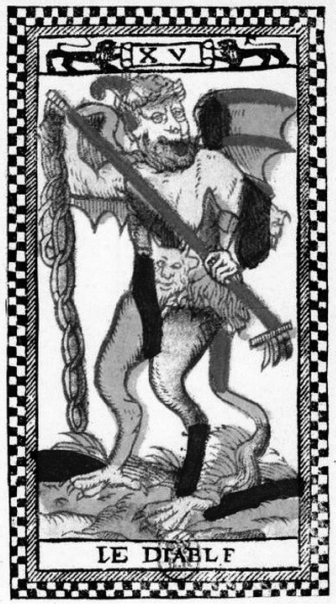

Colonists believed that Satan could affect not just people’s actions but also their health, crops and farm animals. This made his supernatural powers a very real threat. Though it was believed the devil could take many forms, a common image is depicted on this tarot card from the “Tarot de Marseille” deck, created in Italy in the fifteenth century.

Convinced that this “naughtie woman” should stand trial for witchcraft before capital offense magistrates in Hartford, East Hampton judges sent her to the Connecticut Generall Court with a harsh indictment:

[Goody Garlick], that not having the fear of God before thine eyes, thou hast entertained familiarity with Satan, the great enemy of God and mankind, and by his help since the year 1650 have done works above the course of nature to the loss of lives of several persons (with several other sorceries) and in particular the wife of Arthur Howell…for which both according to the laws of God and the established law of this commonwealth thou deserveth to die.

For unknown reasons—no known records exist—Hartford jurors disagreed and found Goody Garlick not guilty. Yet among the many stories that make up Connecticut’s witch trials, hers is a too-familiar one: an older woman unjustly accused of maleficium as a way to explain, or blame someone for, suspicious, tragic or baffling events. Indeed, going as far back as the sixth century—the start of the Middle Ages—almost all of the witches persecuted and expelled from European cities for their “unclean spirits” and “foulness” were women.

For most of history, the stereotypical witch was an ugly and old woman; a hag-like crone with warts, snaggle teeth, a pointed nose and sunken cheeks. It’s an image that no doubt was brought to New England by the roughly twenty thousand Puritans who left England during the “Great Migration” of the early 1600s for greater religious freedom away from leaders of both the Anglican and Catholic churches. Many of these settlers came from eastern England’s Essex region, where for centuries, witches were especially feared and fiercely hunted. Like their diabolical master, witches were hideous creatures, these Puritans believed, inside and out. They were women and men who “signed the devil’s book,” giving the devil permission to take their shape and use them to inflict disease, spoil crops, summon drought and perform any other imaginable and detestable acts.

The purpose of witches was to destroy everything Christians held sacred: their souls, families, communities, churches and lives. Out of this centuries-old certainty came witch hunts that peaked and waned over a period of several hundred years throughout Europe, including Germany, France, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal and England. Pope Gregory XI and Pope Innocent VIII in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were particularly zealous witch hunters, declaring all magic done with the help of demons to be heresy—punishable by burning—and condemning witchcraft as Satanism.

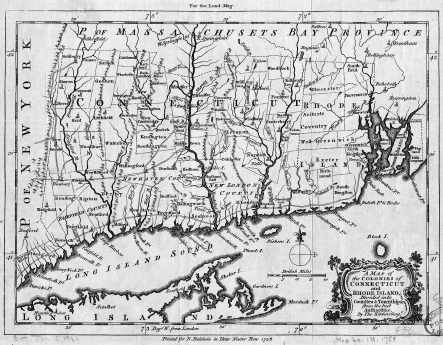

Three Connecticut colonists accused of witchcraft—Elizabeth Garlick and husband and wife Mary and Ralph Hall—were from East Hampton and Setauket. These towns are now part of Long Island, New York. But in the 1600s, they were part of the Connecticut Colony. This early map by Thomas Kitchin and Richard Thomas was published roughly sixty years after Connecticut’s last witch trial occurred.

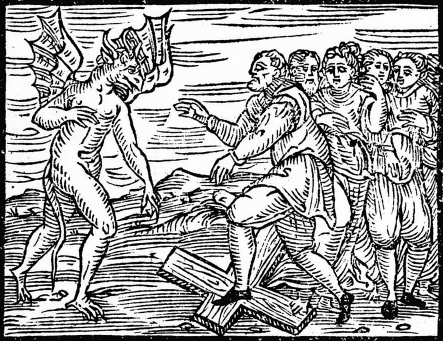

An image from German Catholic clergyman Heinrick Kramer’s fifteenth-century Malleus Maleficarum, which in English means “The Hammer of Witches.” The book is designed to discredit those who believe witchcraft doesn’t exist and details how to identify, trap and prosecute witches.

The fifteenth century also saw the publication of a book in Germany called the Malleus Maleficarum. Translated into English, The Hammer of the Witches provided ministers and magistrates with suggestions on how to best find and convict witches, most of whom, it claimed, were women more susceptible to demonic temptation because of the “weakness of the gender.” Women, the Malleus Maleficarum said, were more carnal and weaker than men. Especially susceptible, asserted Malleus author Heinrich Kramer, were women who tended to overstep the lines of proper female decorum.

The book also accused both male and female witches of infanticide and cannibalism, among other evils, as well as gave women witches the power to steal men’s penises. Through magical attack, the book said, witches could make men’s genitals disappear. They could make them “hidden by the devil…so that they can be neither seen nor felt,” often storing the removed parts in a bird’s nest or boxes, where “they move themselves like living members and eat oats and corn.”

Widely read and deemed by historians to be one of the most influential books of its time, the Malleus Maleficarum played a huge role in shaping New England Puritans’ beliefs about the power and heinousness of witches.

If there were any doubters about the dangers of witches among those who settled Connecticut in 1636, it’s safe to say English witch hunter Matthew Hopkins most likely changed their minds. Letters from family and friends in England told stories of Hopkins, a young man in his twenties who had developed what seemed to be a foolproof strategy for getting accused witches to confess. He outlined his methods in The Discovery of Witches. Published in 1647, the same year Connecticut hanged its first convicted witch, Alse Youngs, the book describes the benefits of “searching” and “waiting,” which requires the accused to sit in one specific position, usually with legs crossed, for twenty-four hours. If the accused was a witch, an imp or devil’s familiar would appear to feed off the witch’s teat.

An engraving from the 1613 pamphlet Witches Apprehended, Examined and Executed, for Notable Villainies by Them Committed Both by Land and Water. The image shows the water test—one of the trials used to prove whether an accused was a witch. A person who sank was considered innocent; a person who floated was guilty.

Other techniques Hopkins used and recommended included sleep deprivation and cutting the arm of the accused with a blunt knife. If no blood appeared, she was a witch. He also used a version of the water test that required the accused be tied to a chair and thrown into water. Those who floated and were rejected by the “pureness” of the water were deemed witches. Those who sank were innocent but often drowned. When an accused did not appear to have any kind of “devil’s mark”—a mole, birthmark, extra nipple or other body mark that all witches were believe to possess—Hopkins shaved off all her body hair and pricked the skin with knives and needles to see whether invisible ones would appear.

The result of these methods was more people being hanged in England for witchcraft over a three-year period than in all the previous one hundred years combined. Between 1644 and 1647, more than three hundred women in England were executed by this self-titled Witch-Finder General.

Letters describing these deaths made their way to Connecticut and elsewhere in the colonies. So did copies of The Discovery of Witches. Journal entries written in May 1648 by Massachusetts Bay Colony governor and Connecticut founder John Winthrop Sr. explain how Massachusetts magistrates followed Hopkins’s “searching” and “waiting” technique to gather evidence on a woman named Margaret Jones and, within that twenty-four-hour period, saw an imp appear “in the clear light of day.” The following month, Jones, a midwife, became the first woman in Massachusetts to be executed for witchcraft.

Although there’s no proof Hopkins’s book played a role in Alse Youngs’s hanging, the timing of its publication and Winthrop’s connection to the Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut Colonies’ judiciaries can’t be overlooked. New England ministers also played their part in stirring up certainty that any threat of witches must be extinguished. Each week from the pulpit of churches in Connecticut and throughout the New England colonies, clergymen warned that even the most righteous were at risk of falling to the devil’s temptations and that those who fell were doomed.

Elizabeth Reis, author of Damned Women: Sinners and Witches in Puritan New England, wrote about these sermons for the Organization of American Historians’ Magazine of History. It’s important to consider their effects:

Ministers make it perfectly clear that intimacy with Satan ended one’s chance of attaining saving grace and damned one to an eternity in hell. They preached that unreformed sinners—those who served the devil rather than God—would be doomed, and they peppered their sermons with images of hell’s dark abyss…In weekly sermons and written tracts, ministers repeatedly admonished their congregations not to fall prey to Satan’s methods. While the devil could not force one to lead a life of sin and degradation, he possessed a frightening array of persuasive tools and temptations and would go to any length to lead people into sin, thereby possessing their souls. Perhaps unwittingly, the clergy’s evocative language and constant warnings about the devil’s intrusions reinforced folk beliefs about Satan, in the minds of both ordinary church-goers and the clergy. The violent battle between Satan and God described in glorious detail in the ministers’ sermons became, during the witchcraft crises, a vicious confrontation between the accused and her alleged victim.