CHAPTER 6

New Incantation

A Quiet Cry to Stop the Witch Hunts

Ye authors warn jurors, etc not to condemn suspected persons on bare presumptions without good and sufficient proofs. But if convicted of that horrid crime, to be put to death, for God hath said, thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.

—excerpt from the Connecticut Colony’s Grounds for Examination of a Witch

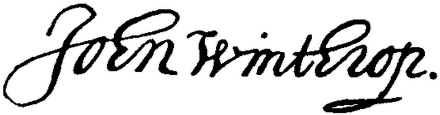

The word “witch” comes from the Old English word “wicca,” which was formed from the Germanic root “wic.” It means to bend or turn. By the very origin of their name, then, witches were those who used magic to bend or turn people and events. During the 1600s, Connecticut governor John Winthrop Jr. also used a form of magic to bend Connecticut colonists’ thinking about witchcraft, playing what undoubtedly was the most significant role in helping end Connecticut’s witch executions. He used the magic of reason.

A physician, alchemist and astronomer, Winthrop’s skepticism about the presences of witches came not so much from a disbelief in magic but a practical understanding of the difference between natural and diabolical magic. Intelligent, inquisitive and diplomatic, Winthrop was deeply interested in science and saw magical processes like alchemy as not just self-serving practices but philosophies that led to greater understanding of chemistry, physics, religion and other aspects of the world. Responsible for bringing the first telescope to New England, Winthrop was also famous for his medical skills, which included an innate ability to diagnose illnesses and prescribe the correct combination of herbs to cure what in some instances were never-before-seen ailments.

A respected physician and alchemist, Connecticut Colony governor John Winthrop Jr. believed people were too quick to attribute “natural misfortunes” to Satan or the occult and spearheaded efforts to end Connecticut’s witchcraft executions.

As curious as he was well spoken, Winthrop saw science and nature as complex, powerful forces that people both overestimated and unnecessarily feared. Magic and witchcraft, he believed, were viewed the same way.

Said historian Walter Woodward in Prospero’s America: John Winthrop, Jr., Alchemy, and the Creation of New England Culture, 1606–1676:

As a consultant on witchcraft cases in New Haven prior to becoming Connecticut’s governor, and then as chief magistrate in Connecticut witchcraft trials, Winthrop consistently refused to accept witchcraft charges, resisting both popular and ministerial pressure to convict witch suspects. He not only orchestrated acquittals in witchcraft cases, on at least two occasions he flatly refused to enforce convictions, ultimately overturning the guilty verdicts.

Elected governor in 1657 after five years as a legislative assistant, Winthrop, until his death in 1676, was an active player in all aspects of life in the Connecticut Colony, including its witch trials. However, it was his involvement in the trial of Katherine Harrison of Wethersfield that ultimately led to him turning people’s beliefs about witchcraft and helping halt what he was sure were unfounded executions.

THE WETHERSFIELD WITCH

Former servant Katherine Harrison married a prosperous farmer and trader named John who, when he died in 1666, left her an estate valued at £1,000. This made her a wealthy woman. The couple had three daughters, and it’s clear she had ambitions for both them and herself. Shortly after John’s will was read, she asked the courts to increase the “inconsiderate” inheritance her husband left their daughters, as well as guarantee Katherine’s use of the family house and farm for the remainder of her life.

Not uncommon for the time, her neighbors, it seems, were jealous and resentful of her new status as landowner. They filed lawsuits against her and began suggesting in public that she had a wicked secret to hide.

One former neighbor wrote the court saying that seven or eight years earlier, Katherine had stolen milk from his cows, but when he attempted to stop her, an invisible force held him stiff until Katherine was gone. Another neighbor named Michael Griswold sued her £150 pounds for slander on behalf of both himself and his wife, Ann. Katherine, he said, had told people that Michael had threatened to hang her and that his soul was damned. She also publicly called Ann “a savage whore” and “other expressions of like nature.”

A healer or “cunning woman” known for being outspoken, Katherine was found guilty of the Griswolds’ charges and ordered to pay them forty pounds. However, she appealed the verdict and, in the court follow-up, begged for leniency. Apparently as smart as she was sassy, she told judges she was “a distressed widow, a female, a weaker vessel subject to passion, meeting with overbearing exercises by evil instruments [that caused me to speak]…hasty, unadvised and passionate expressions.”

Moved by her seemingly sincere admission, judges reduced her fine to twenty-four pounds. But Katherine was not ready to move on. She complained to the court that she was the victim of angry and vindictive neighbors who had attacked her in countless ways. In recent months, she said, someone had beaten two of her oxen, leaving one useless. People had crept onto her property and broken the back and two ribs of one of her cows, destroyed much of her crops and brazenly assaulted a cow standing just outside her front door.

However, what Katherine didn’t know at the time she made these complaints was that her neighbors were also working behind her back to collect written depositions that would accuse her of witchcraft. Once completed, the stack of testimonies compiled over many months from both former and current neighbors accused Katherine of being a witch notorious for everything from lying to being a fortuneteller.

A Hartford man named Thomas Whaples said that when Katherine was living and working in Hartford, she used her supernatural powers, engaged in “evil” conversations and was named by convicted witch Rebecca Greensmith as being part of her coven.

A former co-worker claimed only witchcraft would allow Katherine to spin the amount of fine linen she was able to complete.

A tailor who once publicly said Katherine might be a witch said she came to him in a dream, threatening to get even and debating whether to slit his throat or strangle him before beginning to pinch and torment him. He also insisted she bewitched him at work, causing him to incorrectly sew sleeves on a jacket seven consecutive times and wrongly cut two halves of a pair of pants from different-colored cloth.

Another said she made a calf’s head vanish from the top of a cart of hay and used the strange words “Hoccanum! Hoccanum! Come Hoccanum” to call her cows, which would race toward the house with their tails on end.

One neighbor said he had seen her make bees fly back to their hives and that she afflicted people she was angry at with chronic nosebleeds and burning sensations in their heads and shoulders.

A twenty-year-old described how, over two months, the image of an ugly dog with Katherine’s face would appear in her bed at night, crushing her stomach and threatening to murder her.

Without a son, brother or father to stand up for her against these claims, Katherine was alone, at risk and in many ways defenseless, said author Carol Karlsen in The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England. Katherine was “vulnerable,” Karlsen said. “Within the [Puritan’s] patriarchal system, women were frequently drawn into lawsuits aimed at depriving them of their estates. For Katherine Harrison, it [led to charges of] witchcraft.”

By the time Katherine was brought to trial in 1669, dozens of claims of maleficium had been lodged against her, including those by former patients who said she used her knowledge of herbal medicine to hurt rather than heal. Despite the detailed testimonies submitted about her alleged actions, her formal court indictment was surprisingly nondescript:

Katherine Harrison, thou standest here, indicted by ye name, Katherine Harrison of Wethersfield, as being guilty of witchcraft for that thou, not having the fear of God before thine eyes, hast had familiarity with Satan, the grand enemy of God and mankind, and by his help hast acted things beyond and beside the ordinary course of nature and has thereby hurt the bodies of divers of the subjects of our sovereign Lord the King for which by the law of God and of this corporation thou oughtest die.

Katherine pleaded not guilty, and despite the number and scope of testimonies, the jury was unable to come to a verdict. Katherine was remanded to prison in Hartford until the case could be resumed, but within days, she was back home in Wethersfield. Seeing her there, thirty-eight outraged neighbors petitioned the court, demanding to know “upon what rightful ground she is at such liberty.” They also shared their fear of the “dreadful displeasure of God” and reminded magistrates that Katherine was willing to take the water test, which had not yet been administered.

The signature of John Winthrop Jr., published in 1889 in Appletons’ Cyclopædia of American Biography, volume 6.

When the trial resumed five months later, Katherine was found guilty. But instead of being sentenced, her case was put on hold at the insistence of John Winthrop who, as governor, also served the court as head magistrate.

A man of science and reason, Winthrop was uncomfortable with the jurors’ verdict. Much of the evidence presented against Katherine was spectral, which Winthrop and supporters like the Reverend Gershom Bulkeley of Glastonbury believed was unreliable. Just one person witnessing a diabolical event was no more than hearsay, they believed. “A plurality of witnesses must testify to the same fact” for it to be reliable, Winthrop stated.

CHANGING SPIRITS

Gradual realizations about the need for changes in how witchcraft cases were tried—and Winthrop’s determination to help make it happen—had been brewing for several years.

Although Winthrop was not a magistrate for the 1665 trial of Elizabeth Seager of Hartford, he deliberately involved himself in the case, which represented the third time Elizabeth was accused of witchcraft. Three years earlier, when Elizabeth was first charged, Winthrop was away in England, working to negotiate an official charter for the Connecticut Colony. Then, although more than half the jurors on the case believed she was guilty, there was not enough consensus to execute her, so she was freed. Brought back to trial a second time in 1663 for witchcraft, speaking blasphemy and adultery, jurors only found evidence to convict her on the adultery charge.

For this third case in 1665, Winthrop was also not in the courtroom when the indictment was read:

Elizabeth Seager thou art indicted by the name Elizabeth Seager, the wife of Richard Seager, not having the fear of God before thine eyes, thou hast entertained familiarity with Satan the Grand Enemy of God and mankind and hast practiced witchcraft formerly and continuest to practice witchcraft for which, according to the law of God and established law of this corporation, thou deservest to die.

As governor, however, Winthrop paid careful attention to both the trial proceedings and its effects on the community. What was it that caused neighbors to make public accusations against this woman three different times? Observing the proceedings, he heard claims from Hartford residents who said they had seen Elizabeth pray to the devil. A neighbor, Mrs. Mygatt, said that on at least four occasions, she had seen Elizabeth behaving “strangely,” including a day when Elizabeth came up behind Mrs. Mygatt as she was feeding her calves, grabbed her arm and said, “How do you? How do you, Mrs. Mygatt.” There were claims that Elizabeth had said it was good to be a witch and that the fires of hell would not burn her.

Also not lost to Winthrop was Mrs. Mygatt’s testimony that one night, while she was sleeping next to her husband, Elizabeth appeared in the room, seized her hand and struck her in the face. As had occurred at earlier trials, another neighbor claimed he had seen Elizabeth fly through the air.

What Winthrop heard within these testimonies was ignorance, anger and annoyance toward an unpopular and outspoken woman and, though he might not have defined it this way, intolerance for a woman who was clearly different. He also saw how this trial, as others had done, was causing the community to fracture and was creating fear. As writer and historian Carolyn S. Langdon explains in the January 1969 Bulletin of the Connecticut Historical Society:

[Several men], Governor John Winthrop Jr. among them, had served previously at witchcraft trials, had listened to similar superstitious testimony, had seen accusation lead to accusation as the imaginations of these often unlearned townspeople became fired. Their seemingly frightful accounts were not novel—throughout European history the black cat (or occasionally dog) had been the inseparable mid-night companion of the witch; she had always been able to change her head or her body into animal shapes; to become visible or invisible at will. At her command demons or imps had clutched her victim by the legs and held them fast; she had been familiar with a book from which she derived her unholy knowledge. Such happenings had been commonplace testimony in the hundreds of trials in the English counties from which these people had come. There, as here, in their fear, hatred or envy, neighbors had accused their victim of receiving help from the Devil.

For the testimonies brought against her this third time, Elizabeth Seager was found guilty. Unconvinced, Winthrop asked magistrates to postpone sentencing until they could clarify what he saw as “obscure” and “ambiguous” proof of Elizabeth’s guilt. At Winthrop’s urging, a final decision was delayed for three months, and then another eight months, while he shared his concerns and encouraged other magistrates to do the same. At last, in May 1666, Winthrop called a special session of the Court of Assistants that delivered what would be the final decision in Elizabeth’s case, ruling that the indictment should be “discharged” and that Elizabeth should be set “free from further suffering or imprisonment.”

Three years later, Winthrop felt the same unease and anxiousness when a guilty verdict was issued for Katherine Harrison. But this time around, he wasn’t the only one publicly expressing concern. Like Winthrop and Reverend Bulkeley, other magistrates began to publicly question the types of evidence that should be accepted as clear and actual proof of witchcraft. Determined to use this spark of dissent to affect needed change, Winthrop developed a plan that he hoped would save both Katherine from being hanged and the Wethersfield community from tearing further apart.

Winthrop’s answer? Reach out to Katherine, who he asked to respond, in writing, point by point to every charge made against her. He then requested the court appoint a panel of ministers and magistrates to review her responses and consider not just how they should impact Katherine’s sentencing, but also how they should impact the way future witchcraft cases were tried.

The panel’s answer, though ambiguous in places, sent an overwhelmingly clear message that change was needed. Written by Bulkeley, the panel stated the need for more concrete evidence and shifted the burden of proof from the defendant to her or his accusers. No longer would one witness’s testimony of an event be accepted as fact. For future trials, at least two witnesses to every diabolical event would be required. Panel members also questioned the validity of spectral evidence and issued the following statements:

Moving forward, “a plurality of witnesses [must] testify to one and ye same individual fact; and without such a plurality there can be no legal evidence in it.” Scripture from John 8:17 was cited as the reason for this change, which says: “It is also written in your law, that the testimony of two men is true.” While this first change was not groundbreaking—the need for two witnesses was already an established part of British law—the second was. No longer would claims of specters or apparitions appearing in the form of the accused be allowed as evidence: “It is not the pleasure of the Most High to suffer the Wicked One to make an undistinguishable representation of any innocent person in a way of doing mischief before a plurality of witnesses.”

The panel also argued that God would not permit the devil to create an undistinguishable replica of an innocent person: “This would evacuate all human testimony. No man could testify that he saw this person do this or that thing for it might be said that it was ye Devil in his shape.”

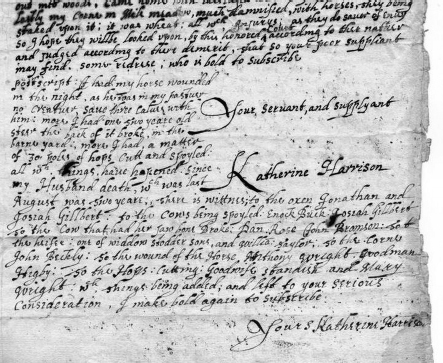

Part of the confession of Katherine Harrison of Wethersfield, who was tried in May 1669 and, among other charges, was accused of bewitching a cap that caused its wearer to be “afflicted by a burning sensation.” Samuel Wyllys Papers, Brown University Archival and Manuscript Collections.

Their final points tackled whether fortunetelling or “discerning secrets” about the future was an unquestionable sign of association with the devil:

Those things, whither past, present or to come, which are indeed secret, that is cannot be known by human skill in arts or strength of reason arguing from the course of nature or…by divine revelation…nor by information from man must needs be known (if at all) by information from ye Devil…the person pretending the certain knowledge of them seems to us to argue familiarity with ye Devil.

Predicting the future was indeed a sign of diabolical involvement, the panel said. Yet as many historians have written, these changes, coupled with opinions formed over Katherine Harrison’s case, in many ways marked the beginning of the end of Connecticut’s witch trials. For Katherine, they also meant she would not face the noose.

Similar to what occurred at the end of the Elizabeth Seager trial, Generall Court magistrates in May 1670 called a special session of the Court of Assistants to meet in Hartford and, with Deputy Governor William Leete presiding, issued the final decision on Katherine’s sentencing:

This Special Court having considered the verdict of the jury respecting Katherine Harrison cannot concur with them so as to sentence her to death or to longer continuence in restraint do dismiss her from her imprisonment, she paying her just fees. Willing her to mind the fulfillment of removing from Wethersfield which is that which people will be the most to her own safety and contentment of the people who are her neighbors.