CHAPTER 9

Bewitched

Myths and Mistruths About Connecticut’s Witch Trials

For conviction, it must be grounded on just and sufficient proofs. The proofs for conviction are of two sorts. Some be less sufficient, some more sufficient. Less sufficient, used in former ages, by red hot iron and scalding water. Ye party to put in his hand in one or take up the other. If hurt, to be convicted for a witch.

If not hurt, ye party cleared, but this as utterly condemned…Another insufficient testimony of a witch is ye testimony of a wizard…he [is] diabolical and dangerous, ye devil may represent a person innocent.

—excerpt from the Connecticut Colony’s Grounds for Examination of a Witch

Of course, the greatest mistruth about Connecticut’s witch trials is that none ever occurred, or that the Salem trials came first, or that the Salem witch trials were the only or most heinous in New England. But even among those aware that Connecticut experienced its own witch panic, there are many mistruths. The fact that so few documents exist from the time period only causes the line between reality and myth to blur that much more.

Most myths and legends are based in history. But as journalist Heather Whipps explains on the LiveScience website, they also offer insight into our fears, attempt to explain things we don’t understand and, maybe most importantly, can be great fun. “Life is so much more interesting with monsters in it,” University of Wales folklorist Mikel J. Koven told her.

Like many academics, Koven said he believes most myths and legends are at least partly based on truth. But problems occur when fictional stories start being taken as fact.

Searching seventeenth-century gravestones will lead to many that are engraved with a winged skull, symbolizing the ascension into heaven. However, under none of these stones will be the bodies of convicted witches. Connecticut residents executed for witchcraft were buried in unmarked graves. Their locations are unknown.

Hartford’s Trinity College in 1909. Many believe convicted witches were hanged at Trinity’s Gallows Hill. However, the only proven executions to occur there were of a handful of British Loyalists during the Revolutionary War.

An 1881 issue of a monthly magazine called Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly can be credited with perpetuating—or perhaps even creating—at least one false, though entertaining, story about a supposedly hanged witch named Juliana Cox from Glastonbury. According to the Popular Monthly article, a clipping from an 1823 Hartford Times was found in the scrapbook of a Glastonbury resident about Juliana, who in 1753 “was one of the few who were hanged in Connecticut.” Her death was part of the “witch business” begun “before Massachusetts,” said Popular Monthly editors, who wrapped their article around an illustration of a frightened Puritan woman cowering on the ground as a dog bites her shoulder and a man, pointing and yelling, arrives with a musket.

The article goes on to say Juliana Cox was executed on “Gallows Hill in Hartford…now known as the commanding trap-rock ridge by the stone-pits.” Likely referring to the steep stone cliff near the corner of Vernon and Summit Streets across from what’s now Trinity College’s St. Anthony Hall, this particular spot has for decades been wrongly identified as a location where witches were hanged, though a clarification is needed.

Gallows did once stand at Trinity College’s Gallows Hill, but not during Connecticut’s witch panic. One hundred years later, during the Revolutionary War, the Patriot army hanged three or four British Loyalists there—but no witches, just like there was likely no Juliana Cox.

“I feel pretty confident saying that if a witch lived in Glastonbury, and was executed as late as 1753, we’d have some kind of evidence,” said James Bennett, director of the Historical Society of Glastonbury. “Record-keeping in the mid-eighteenth century was much better than a century before” when the majority of Connecticut’s convicted witches were hanged.

Library and Internet searches for the Hartford Times article that Popular Monthly cites also lead to nothing. But even if the Popular Monthly article was meant to be a joke, it’s easy to see why many might have taken it as truth. Names, dates, times and places are written as if they were gospel, and descriptions of Juliana’s words and actions are similar to those that occurred at several actual trials and hangings. The piece is also written with journalistic authority, with details that go as far as listing the names of official “committee members” charged with examining Juliana for witch marks. Here is the article:

In the beautiful town of Glastonbury, in Connecticut, the following remarkable event occurred in 1753: In March of that year, one Julius Perry went out with his dogs to hunt. In the depths of the forest, he discovered (as he alleged) an old gray fox, and his dogs gave chase. After chasing this fox upward of two miles, the animal was holed. When Mr. Perry came up, he heard a strange noise over the other side of the hole, and going to the spot, he found Juliana Cox lying and panting for breath. Her left shoulder was bleeding, and had on it the marks of the dog’s teeth. This was just the spot on the gray fox’s shoulder where the dogs had seized hold. Upon this testimony, Miss Cox, a maiden lady of forty-four, was brought to trial for the capital offense of being a witch. On her arraignment, she pleaded not guilty, and it was determined that a committee of selectmen should examine her person for witchmarks, in order to introduce confirmatory proofs against her. She was, therefore, remanded to prison.

The following persons were appointed on the committee: Eben Brewer, Alexis Jones, and Samuel Cutworth. These men proceeded at once to the prison, and stripping Miss Cox, they began their examination. For a time, exceeding an hour, they could find no marks, and Miss Cox submitted to their examination with tears and sobs. Finally, when they had pricked many places on her body without success, she confessed to two marks—one a little below the right hip and one on the left arm. The committee now became satisfied that there were true marks, as the flesh was thereon discolored in a slight degree. They thereupon made their report to the court appointed to hear the trial.

This evidence, confirming that of Mr. Perry, was thought to be conclusive, and on the 3d of April the trial took place. It was thought unnecessary to resort to further tests, and Miss Cox was found guilty of witchcraft on the evidence already quoted, and sentenced to be hanged. Strange noises and demons haunted the jail at Hartford up to the time that her execution took place, which was on the 7th of April, at five o’clock in the morning.

There was a large concourse of men and women attending her execution, and, although she declared that she was unjustly accused and that she confessed to the witchmarks to stop the pain of being so cruelly pricked by the committeemen, yet every person present believed her to be a true witch, and in league with the devil. She further declared that Julius Perry accused her wrongfully. She said she was in the forest gathering herbs, and that Julius Perry came along and would have his will of her; that, she constantly refusing, he set his dog upon her, and the animal bit her shoulder; and that he, fearing to be detected in this bad act, had laid the charge of witchcraft against her. This she said under the gallows. Whereupon a shout was made among the people to “burn the witch!” as hanging was way too easy a death for so foul a strumpet of the devil. While the people went to fetch wood to burn her, the sheriff hung her up, so that she died on the gallows before the wood could be brought.

The story of Julius Perry and Juliana Cox is convincing and entertaining but entirely untrue. But thanks to the fact that all of Popular Monthly’s nineteenth-century issues exist online in digital form, it exists in perpetuity for anyone to find, believe and share with others. And it’s not the only lasting source of mistruth.

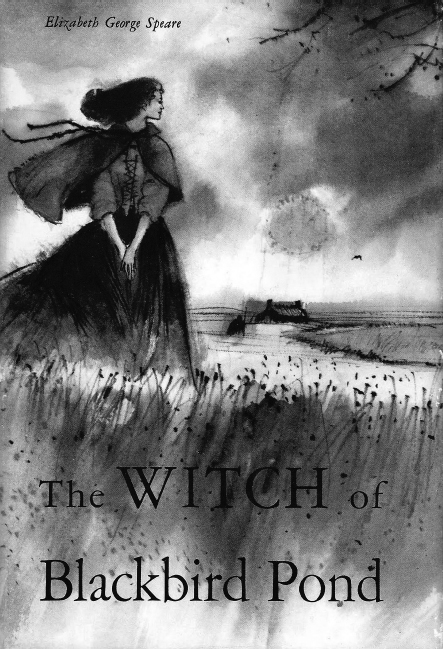

The Newbery Medal–winning children’s novel The Witch of Blackbird Pond by Elizabeth George Speare is based on accused witches from Wethersfield. Published in 1958, it’s still part of many school curriculums. Houghton Mifflin Company.

As journalist Chris Pagliuco said in a 2007 article in the Hog River Journal (now Connecticut Explored Magazine), it’s ironic that one of the most prominent sources of information about Connecticut’s witchcraft history is also the source of much misinformation. His comment refers to the much-beloved 1959 Newbery Medal–winning novel The Witch of Blackbird Pond, which for decades has been required reading for middle-schoolers around the country.

Written by Massachusetts author Elizabeth George Speare (who in 1962 won another Newbery for her children’s novel The Bronze Bow), the book tells the story of orphan Kit Tyler, who, after her grandfather dies, travels by ship from her home in Barbados to live with her Aunt Rachel and Uncle Matthew in Connecticut’s Wethersfield Colony. The only place she feels free in this strict, Puritan community are the meadows, where she makes friends with an old Quaker woman known as the Witch of Blackbird Pond. When Kit’s friendship with the “witch” is discovered, Kit is accused of witchcraft.

Comparing fiction with fact, the latter occurrence makes much sense. Being a “companion…of a known or convicted witch” was one of the colony’s “Grounds for the Examination of a Witch” and often came into play. Other details and circumstances, however, don’t add up to reality, said Wethersfield Historical Society volunteer Martha Smart, who for fourteen years worked at the Connecticut Historical Society as a reference librarian.

“Although it happens in the book, no one accused of witchcraft in Wethersfield was actually tried in Wethersfield,” said Smart, who several times a year leads historical tours of downtown Wethersfield that include a stop at the Buttolph-Williams House on Broad Street, which is featured in the novel. She and other docents there also tell the story of Mary Johnson, the Wethersfield woman and first colonist to admit to witchcraft, who is the focus of Chapter 3.

Smart continued:

Unlike the “witch” in The Witch of Blackbird Pond, no woman in any Puritan community would be allowed to live alone, even if she were considered strange or an outcast. Married women were required to live with their husbands, and unmarried women to live with family members. Also, Quakers and Puritans did not mix. They lived in separate communities. But even though Puritans saw Quakers as dissidents, they would not persecute them as witches on religion alone. Remember that the Puritans left England for religious freedom, so even though they did not agree with the Quakers, they certainly did not attack them. Blackbird Pond is a great story, but it needs to be treated as such—as a story. It doesn’t portray the truth of Connecticut’s struggles with witches, though it can be used to teach tolerance and the need to be more accepting of those who are different.

Old women are frequently portrayed as crones or witches—even in young children’s books. This Victorian-era image, whose artist is unknown, is believed to have accompanied a little-known Mother Goose nursery rhyme that goes like this: “There was an old woman tossed in a basket/Seventeen times as high as the moon;/But where she was going no mortal could tell,/For under her arm she carried a broom.”

Also important is the fact that The Witch of Blackbird Pond is set in 1687: the last year of what state historian Walter Woodward called “a quarter-century of silence where witch hysteria faded and not a single witchcraft execution occurred.”

To combat these and other myths—especially those that have to do with broomsticks and pointed hats—Lisa Johnson from Farmington’s Stanley-Whitman House urges research, particularly related to individuals affected by the witch trials. “We know that on the state level, documents don’t exist anymore. That makes research on individual people critical. I’m sure that hidden in boxes and attics and cellars are letters and diaries that can give us details about at least that particular person involved. And the more we known about each individual person, the better we will be able to put together the overall story.”

So what fanciful facts about Connecticut’s witch trials are true? Sir Winston Churchill, former English prime minister and one of the most significant world leaders during World War II, is a descendent of Mary Staples of Fairfield. Mary was accused of witchcraft in 1654, exonerated and may have been charged again in 1692, though records are inconclusive.

Lexicographer and textbook creator Noah Webster, whose name in the United States has become synonymous with “dictionary,” is a descendant of Lydia Gilbert of Windsor, who was tried and hanged in 1654.