Lukin’s A Force advance alone into German territory

3

The Sandfontein reversal

BRIGADIER GENERAL HENRY LUKIN was the antithesis of Lieutenant Colonel Manie Maritz. For starters, he was English and the quintessential British officer. Born in 1860 into a family with a long military tradition, he was sent to the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, where, although proficient in the practical aspects, he found the exams too difficult and failed. Undaunted, he tried another tack. In early 1879, Lukin sailed for South Africa with the hope of volunteering for duty in the Anglo-Zulu War. He was drafted into a labour unit in charge of preparing roads into Zululand so that soldiers and wagons could move rapidly en masse. Luckily, a passing cousin and adjutant in the military persuaded his commanding officer to enlist Lukin as a fighting officer and he was immediately made a lieutenant in a mounted brigade. Lukin fought and was wounded at the Battle of Ulundi that saw the Zulus finally defeated.

After the war, Lukin remained in South Africa and served in the Cape Mounted Infantry, the only standing unit in the Cape Colony at the time. From then on he fought in skirmishes against the Basotho and the Xhosa. He was promoted to captain and sent to England where he did courses on artillery and the new Maxim guns. He returned to fight in the Boer War and became regiment commander of the South African Mounted Infantry shortly afterwards. In 1912, Smuts made him a brigadier general and put him in charge of the Permanent Force. In August 1914 he was given orders to muster troops in Port Nolloth. By September, he was in Steinkopf, commanding A Force and about to attack the German colony from the south.

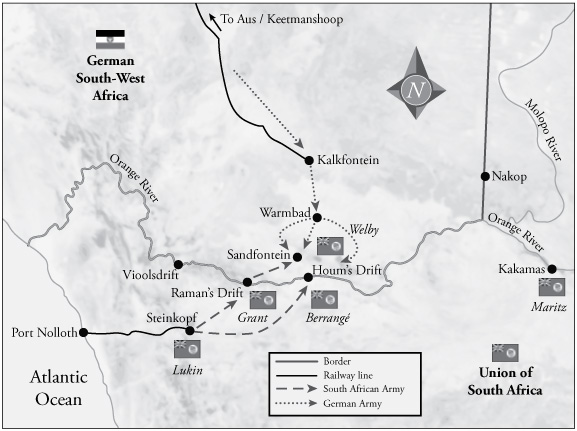

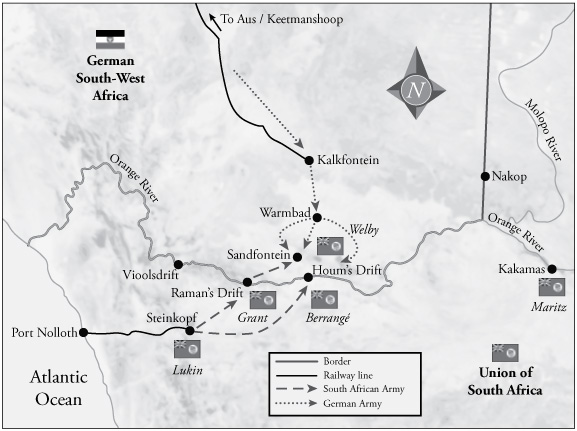

On 11 September, Lukin sent ahead a reconnaissance team to scout the near bank of the Orange River. The following day he received the order from Pretoria to proceed into German territory. Lukin immediately dispatched two squadrons of mounted riflemen under Colonels Dawson and Berrangé to occupy and secure the two fordable places on the Orange River, Raman’s Drift, about sixty kilometres north-east of Steinkopf, and Houm’s Drift, a few kilometres further upstream. On 14 September, they were secured after some light skirmishes, the small German units retreating quickly north into the mountains. On that same day along the coast, the Royal Navy bombarded Swakopmund. The Germans, according to their pre-war plans, evacuated the town without loss of life. Five days later, Lüderitz was also shelled and occupied from the sea.

From Steinkopf, Lukin endeavoured to push his main force further north, but soon realised that the considerable distance over harsh terrain to the river was a great deal more challenging than headquarters in Pretoria had previously conveyed. He had been given only enough water and supplies for about a quarter of his force to move forward comfortably. Lukin requested a light train line to be laid from Steinkopf to the river in order to improve his supply issues, but he was denied on account of expense and time. His next request, that he be given three weeks’ grace until he had enough supplies and draft animals to move his whole force forward, was also denied. It was a grave mistake.

Lukin was instead ordered to rapidly push on to the first well on the German side of the Orange River, at a place called Sandfontein, about forty kilometres north-east of Raman’s Drift. This manoeuvre was designed to eventually take the strategic southern village of Warmbad, which lay a further sixty kilometres north-east. The plan devised in defence headquarters was for Lukin’s advance units to link up with the advance of Maritz’s B Force coming up from Kakamas on the right. Pretoria had assured Lukin that the Germans only had small detachments in the south. Their main force, it was believed, was still in Windhoek, hundreds of kilometres away. This, notes Collyer, was probably correct, but what Pretoria failed to understand was that the Germans could rapidly deploy their entire force, with the necessary supplies, from anywhere in the colony down the railway line to its southern terminus at Kalkfontein Station, just to the north of Warmbad, in less than a day.1

Lukin was undoubtedly aware of his overall predicament, he probably had been from the beginning, but he was not a man to question orders. He had tried to cooperate with Maritz on his right flank, his only support, by wiring the lieutenant colonel before occupying the river crossings, asking him to coordinate his attack. Maritz had replied that he was not ready to move, allegedly telling an adjutant that Lukin could ‘stir in his own juice’, such was his abhorrence for the British officer.2 Lukin, wise to Maritz’s questionable allegiance, was therefore non-committal with information about his own movements and relayed his concerns about Maritz to Smuts in Pretoria.

On 23 September, Smuts sent a telegram to Maritz ordering him to mobilise his detachment in two columns at Upington and Kakamas respectively, and to advance immediately on the border. Maritz’s long diatribe in response revealed that he had never had any intention of mobilising. He argued that the men of the Active Citizen Force under his command were of no military value and that his force was the only one of the three without artillery, and he could not therefore weaken it further by dividing it into two columns. He berated the South African government for moving against the German South West, which had made his ‘position very difficult’, and he threatened to resign should he be forced to take part.3 Lukin was on his own.

On 24 September, Lukin dutifully sent a squadron of 100 rifles from the 1st South African Mounted Rifles under Captain E.F. Welby to secure Sandfontein, while a second squadron under the regiment’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel R.C. Grant, replaced Dawson’s men at Raman’s Drift and prepared to follow Welby a few days later. A third squadron painstakingly made its way to the river from Steinkopf. Lukin himself arrived at Raman’s Drift later on the 24th to establish brigade headquarters.4 A drum telephone line was rolled out to Sandfontein, providing a direct link to Welby, who was ordered to gather intelligence from local Nama about the movements of the small units of German soldiers operating in the mountainous area north of the Sandfontein well. Berrangé, at Houm’s Drift, was also ordered to scout his front and report to brigade headquarters.

According to Collyer, the reconnoitring intelligence corps’ use of local Nama scouts had two chief faults.5 Firstly, while intimately knowledgeable about the landscape, the Nama were unable to provide reliable information from a military perspective. Numbers of soldiers and descriptions of materials were often not provided or deemed unimportant. Secondly, because they were at pains to please, they tended to provide answers that the questioners seemed to want to hear, at the expense of accuracy. Furthermore, the maze of mountains around Sandfontein made it virtually impossible for even the best scouts to gather an accurate picture of enemy troop movements and numbers. Lukin may as well have been operating blind.

While Lukin manoeuvred his troops, Colonel Beves landed with C Force at Lüderitz unopposed. The German command saw defence of the small port as futile – the vast natural fortification of the Namib would be C Force’s real enemy – so they wisely pulled back inland, making for Aus, a small village perched just behind an imposing wall of mountains with a commanding view of the waterless plains to the west. Behind them, on a higher elevation to the east, was plenty of grazing and water for their animals, as well as the railway track that branched from Keetmanshoop, so their supply line was well organised and efficient. The Germans meticulously destroyed the railway line behind them and poisoned or destroyed the few waterholes along the way. This left Beves the tedious and unenviable task of repairing the line as he advanced the 120 kilometres to Aus. He could only move as fast as the tracks were laid and even then had to keep doubling back to replenish his force. It was a case of two steps forward, one step back. In short, C Force was going nowhere, which left the Germans able to combine the forces facing C Force with those about to face A and B in the south.

With Maritz refusing to take action, rather than commit hara-kiri by advancing on Warmbad, Lukin concentrated on securing his own position on the river and his advanced position at Sandfontein. On 25 September, intelligence from Sandfontein reported that a squadron, two at most, of Schütztruppe had been seen about thirty kilometres north-east of Houm’s Drift. In addition, dust from an unknown body moving south from Warmbad had been observed, but no indication of size or strength was available. Lukin assumed he was facing a force of some 300 strong with the intent to attack his forward position at Sandfontein.6 On that same day, Welby telephoned to tell him that Sandfontein could not be defended against attack unless the surrounding heights were occupied. Welby was concerned that his rear was not sufficiently protected either. For this he needed more men. He also informed Lukin that he was on his last day’s rations and supplies were long overdue.7

After reassuring Welby that aid was on its way, Lukin ordered Grant to hurry north with two 13-pounder quick-firing field guns, a machine gun and three troops of his squadron to reinforce Welby’s squadron. Lukin also began to prepare another squadron to follow Grant in an effort to secure Welby’s rear.8

The urgency was such that Grant could not wait for his ponderous supply wagons. In the early hours of 26 September, he was ordered to push on ahead with the expectation that his supplies would arrive later that evening. The problem for Grant, however, was that all his reserve ammunition was with the supply wagons. Normally this would have accompanied him, but, given the scarcity of transport, Lukin could not spare extra mules to transport the reserve ammunition separately, even after Grant had implored him.9

Lukin’s A Force advance alone into German territory

Grant reached Sandfontein at 7:25 on the morning of 26 September. Silver-haired and regal, and a seasoned campaigner and fighting man, Grant knew his trade, and immediately upon arrival he realised that the situation was, as Collyer records, ‘extremely bad, difficult to hold against any superior force, and untenable against artillery’.10 Sandfontein, although important as a well point, was a weak defensive outpost.

The area is centred on a conical-shaped hill or koppie just less than 100 metres high, with a long spur jutting to the south-west. To the south, north and east, the koppie is dwarfed by an imposing semi-circular range of mountains, which would have been well within range of First World War–era artillery. To the west, an open plain rises gradually to dominate the koppie, which itself sits in a dip with a dry river bed sweeping past it to the south. In 1914, the well, situated at the western foot of the koppie, was accompanied by a single square stone kraal, where mules and horses were kept, as well as some sheds.

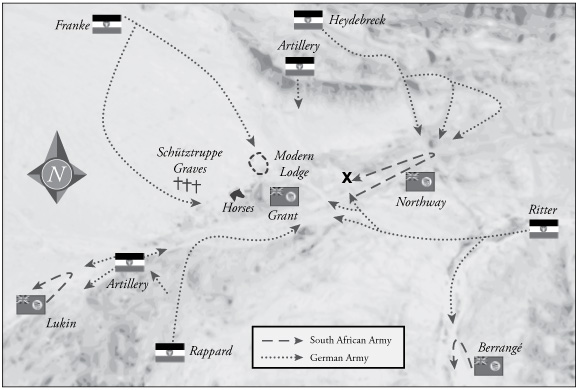

Grant requested an urgent meeting with Welby to discuss their untenable position. Since their arrival two days earlier, Welby’s engineers had built rows of protective schanzes at varying levels around the koppie, but the ground was too rocky to construct deeper trenches and there were no suitable gun positions. As the two men talked, a message came from the top of the koppie that a column of Schütztruppe was advancing rapidly from the direction of Warmbad in the north. Almost at the same time, news arrived that the telephone line in the rear had been cut.

Grant rushed to the top only to discover three more columns moving at a gallop from the east, west and south-west respectively. The German column to the east was under the command of Major Hermann Ritter, while that to the west was led by Major Viktor Franke, who would later feature prominently in the campaign. On the rise to the south-west, Major Emil von Rappard’s mounted column – which had somehow gone undetected by Grant on his approach from Raman’s Drift – bore down on them at full tilt. In Grant’s own words, ‘Within twenty minutes of my arrival it was evident that my detachment was completely enveloped by a greatly superior force.’11

The Germans’ northern column under the command of Major von Heydebreck was being slowed somewhat by the brave fighting retreat of a scout patrol under Lieutenant Northway, which Welby had sent out to reconnoitre the area less than an hour earlier. Northway was forced to dismount in order to better check the advance, but he and his men were effectively pinned down and cut off from the main body on the hill.12

At 8 a.m. Grant ordered both his 13-pounders to open fire on von Rappard’s southern column, which had the immediate effect of halting their advance. The barrage was answered, however, by four German light field guns from the mountains to the north, and later by another four from the south-west. With a total of eight artillery pieces firing on Grant and Welby’s central position, it was a most unequal artillery battle. It was not long before the two South African 13-pounders ceased firing: a direct shell hit killed the entire crew of the one, while the other was abandoned after sustained shelling, but not before being put out of action by the heroic efforts of Lieutenant Adler, the young officer in charge of the gun crew, who, along with most of the other men, was witnessing battle for the first time.13

With the 13-pounders gone, the koppie was raked at will by enemy artillery and machine-gun fire as lines of dismounted German soldiers slowly advanced. The Schütztruppe concentrated their fire first on the poor mules and horses tethered in the kraal at the foot of the hill, and in minutes only one or two fatally wounded animals remained standing.14 They then enfiladed the heights. Grant was severely wounded at the top of the koppie and ordered command to be handed over to Welby, who was at the northern foot. It is not known if Welby received the order, which had to be shouted by Grant’s adjutant. In any case, with the searching fire it was impossible for Welby to ascend and effectively take command.15 Nevertheless, the South Africans courageously held their defence, beating off repeated waves of attack with well-placed rifle shots.

There was a distinct lull in the fighting at around 1 p.m., when the Germans took their lunch.16 The South Africans had no such luxury. They had been without food and water for a day already. The sun beat down relentlessly on the exposed hill, fuelling the discomfort of Grant’s squadron especially, which had not slept since departing Raman’s Drift in the early hours of the morning.

At 3 p.m. the Germans moved their artillery in closer and started exacting a heavy bombardment on the weak redoubts. Northway and three others who had been pinned down all day decided to make a dash for the koppie. All three were cut down by machine-gun fire, and the remainder of the patrol surrendered.17

The only hope now lay in a relief force from either Lukin at Raman’s Drift or Berrangé at Houm’s Drift. In fact, at midday Grant’s men had heard distant fire in the direction of Houm’s Drift. Berrangé had gallantly tried to come to their rescue, but had been held back by enemy detachments placed in defensive positions in the mountains along the dry watercourse of the Hom River specifically to counter such efforts. At Houm’s Drift, the main channel splits into a series of narrower ones, making it easy to ford. As a result, the Germans had not bothered to line their defences at the crossing, preferring to hang back in the mountains from where they could pick off the approaching South Africans.

At the Battle of Sandfontein, the South African advance troops are completely surrounded and cut off from the main body

Lukin, too, had tried to relieve the men at Sandfontein. He had activated the entire force for the rescue as soon as he heard the first salvos, but because of the supply problems he only arrived the following day. Then, on seeing the superior size of the German force blocking his path, he had prudently fallen back on Raman’s Drift.

The wounded Grant was under no illusions as to their situation. He knew Lukin did not have a big enough relief force to break the German lines. His own ammunition was running low (his reserve ammunition, with the supply train, had barely progressed beyond Raman’s Drift when the fighting began); his men were hungry, thirsty and exhausted; and, although the enemy had been held in check, the approach of evening meant there was no hope of repelling an attack under the cover of darkness. Surrender was their only real option.

At 6 p.m., after ten hours of heavy fighting, Grant resumed command to raise the white flag. He was escorted off the field of battle on a makeshift stretcher carried by Nama bearers. South Africa’s first battle as a united nation had ended in defeat.

It was not an ignominious defeat, though. The South African defenders could hold their heads high. Almost seventy were killed, about 25 per cent of their total number at Sandfontein, but they had had to contend with an enemy force ten times as large and an artillery four times as powerful.

When the white flag went up, both sides dropped their weapons and rushed towards each other to the well directly in between their lines. Here, amid frenzied gulps, the combatants mingled freely like the players of two exhausted teams at the end of a gruelling rugby match. Von Heydebreck personally congratulated the wounded Grant on his gallant defence and ensured he got the correct medical treatment.18 Grant and the walking wounded were immediately dispatched to Warmbad along with all the unwounded rank and file. They would sit out the rest of the campaign, languishing in prisoner-of-war camps at Otavi and Tsumeb in the north of the country. The severely wounded were sent back to their own lines at Raman’s Drift and both sides assisted in burying the dead.

No one could argue with Grant’s decision to surrender. Lukin’s report on the battle states:

[Grant was] a thoroughly good Commanding Officer, who takes the keenest interest in everything pertaining to the efficiency of his Regiment and the welfare of those serving in it. He is in no way responsible for the regrettable incident at Sandfontein, where his Command put up a fine fight against overwhelming odds.19

While Lukin, sensitive to those under his command, personally accepted a large portion of the blame, no one could hold him at fault. He was simply acting on orders from his superiors in Pretoria, who, it must be said, accepted their responsibility. Lukin should instead be commended. His cautious military mind prevented him from bringing his entire force forward to Sandfontein. Given the enemy’s strength, he may have lost far more than a single detachment if his whole force had been surrounded and either killed or forced to surrender. As it was, Lukin was still able to hold the river as the German commander was loath to cross into South African territory. In the end, the Union troops suffered relatively few losses.

Back at defence headquarters, Smuts realised his insistence on moving forward had been ill-advised. Furthermore, he had underestimated the Germans’ use of the railway system to rapidly concentrate the Schütztruppe on desired targets. What is worse is that Pretoria had got wind of a concentration of German troops in nearby Kalkfontein beforehand. A staff officer had then posted this information to Lukin, who received it ten days after the Sandfontein reversal. Had the information been relayed by telegraph, Lukin would have known that the bulk of the enemy force was swooping down on him and he would never have dared push beyond the river.20

Credit must go to the German commander, von Heydebreck, who utilised his natural defences to nullify the threat from C Force and direct his full attack on Lukin’s A Force. He also used the terrain around Sandfontein to his advantage and correctly predicted the movements of the South Africans, who only realised their mistake after they had occupied the koppie. Had Grant been given just a little more time, he most certainly would have abandoned the hill for a stronger position, possibly a section of the surrounding mountains. Von Heydebreck’s rapid deployment revealed the cracks in the Union’s reconnaissance system as well as in their lines of communication.

Von Heydebreck had the upper hand, however. As early as 1911, he had provided a full report on the advantages of aircraft in both reconnaissance and offensive manoeuvres and, as a result, acquired pilots and aeroplanes that were tested in the months before the war. The colony’s three planes included an Aviatik flown by Lieutenant Paul Fiedler and an LFG Roland biplane piloted by Lieutenant Alexander von Scheele. The third was an unidentified craft (probably a Taube or a Roland) flown by its civilian owner, a factory pilot named Willy Trück. All three planes were modified for war, and were equipped with a compass, a camera and a signal mirror for emergencies. They all had a range of between thirty and fifty kilometres, although the Aviatik had a steeper rate of climb and was easier to maintain. The pilots were provided with food rations, water bags, tools, tents and a rifle with ammunition, as their planes were prone to crash, and often did, but usually with no serious consequences for the pilots or the aircraft.

The opening phase of the war provided an opportunity to test these aeroplanes’ capabilities and von Heydebreck used them effectively to gather information on troop movements, specifically Lukin’s A Force at Steinkopf. These aircraft held the accolade of being the first, and last, to violate South African airspace. It was also the first time aerial photographs were used to record ground information, which von Heydebreck was then able to use with surprising accuracy. This may explain the ease and speed with which he attacked Sandfontein.

The German commander also had forewarning from Maritz that B Force would not be a threat. If anyone is to blame for the reversal, it is Maritz: for failing to lend support to Lukin and for his complicity with the Germans. His two attacking columns could have weakened the Schütztruppe by splitting their force in three. Despite this, however, Collyer argues that it is uncertain whether B Force’s involvement would have made much difference against a numerically superior German force. Maritz knew this, as did the South African commanders, who were forced to reassess their position. Smuts immediately sent General Brits to replace Maritz and then went back to the drawing board to re-evaluate the campaign.

These days the area around Sandfontein and the two crossings, Raman’s Drift and Houm’s Drift, is remote, even by Namibian standards. You will not find Sandfontein on any printed map. Today it is the site of an upmarket game lodge that forms part of the Sandfontein Nature Reserve. At 76 000 hectares, it is the third-largest private reserve in Namibia and is home to some 4 000 animals, including the rare black rhino. Activities include hunting, horse riding, game and scenic drives, rhino tracking, canoeing on the Orange River, and relaxing at the lodge’s twenty-metre swimming pool. It is not a cheap destination. In 2014, a bungalow cost about R3 000 or €200 a night.

Looking up from the lodge towards the koppie today, one can see just how exposed to machine-gun and shell fire the South African troops were. There is precious little shelter from top to bottom. At the foot of the western slope, a shed that looks to be original is dwarfed by a new, large and ostentatious house – apparently a shareholders’ holiday residence. When they dug the foundations for the new building they found a lot of equine bones, most likely those of the horses and mules that were mowed down by the Schütztruppe at the beginning of the battle. The local Nama believe the house is haunted.

Climbing to the top of the koppie, one passes row upon row of redoubts, the very ones that Welby had his men construct. They are the physical monuments, the obvious reminders of the battle. It seems that not a stone has been removed; even the rifle holes are still visible. One can picture South African soldiers hunkering down behind their schanzes, careful to keep their heads low, swarms of bullets whizzing past and pinging into the rocks all around them, then the whine of a shell, an awful explosion, rocks and metal flying about, shouts, screams, cries …

Bits of rusted metal litter the ground. They are mostly old beer cans, presumably left by farm labourers over the decades, but some are the older and much thicker rusty fragments of artillery shells. From the top of the koppie, the view to the north-east is dominated by the high buttress where four of the German artillery guns were positioned, raining hellfire on the hapless defenders. To the east, a dry riverbed sweeps past and joins another heading south towards the Orange. Beyond that, clothed in deep ochre, are the mountain ranges that dominate the position on three sides.

Visible on the wide plain to the west are the white marble gravestones of German soldiers. Fourteen were killed that day, including Major von Rappard, who was commanding the column advancing from the south-west. Exposed on a rocky path that descended to the riverbed, it was they who Grant’s 13-pounders found first. They took a heavy toll. Von Rappard’s death especially was a huge blow to the German military endeavour and would prove to have a negative impact on Germany’s overall defence of the colony. A Prussian aristocrat with a fine military background, he was astute and popular among his men. He was also von Heydebreck’s second in command.

The view from the koppie south of Sandfontein is dramatic. The twisted mountains reveal how difficult it must have been for Berrangé to attempt to relieve Grant. They formed an effective cover for the encircling German force. Although Houm’s Drift is not an official border crossing today, it is often used for illicit cross-border activities. The area on both sides remains remote, making it easy for the illegal flow of alcohol, drugs, weapons and other contraband. These days a different kind of armed invader is attempting to cross into the former German territory: poachers going after Sandfontein’s black rhinos.