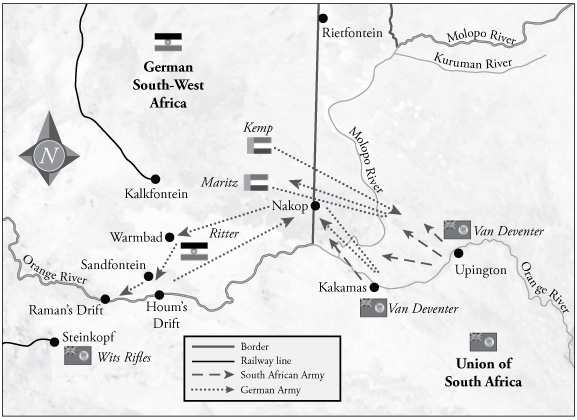

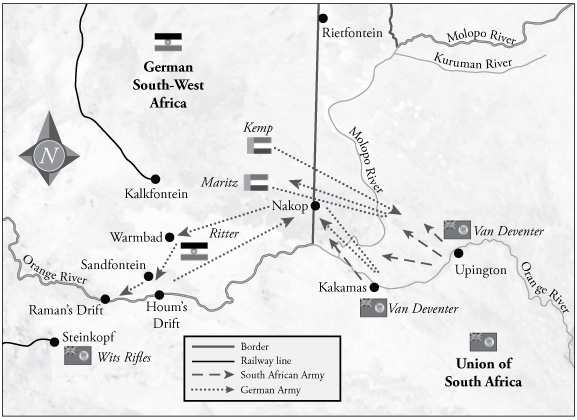

Major Ritter’s abortive incursion into the Union. It was the first and last time South Africa as a nation was ‘invaded’

4

Insurrection

ON 28 SEPTEMBER, TWO days after the battle at Sandfontein, and probably as a result, Botha personally took over Beyers’ position as commander of the Active Citizen Force, which he then amalgamated with Lukin’s Permanent Force, thus taking overall command of the Union Defence Force as commander in chief and relieving Smuts of the responsibility. Botha also appointed a real soldier, Brigadier General J.J. Collyer, as his chief of staff.

Botha called for more volunteers to bolster his meagre forces along the border, stating that if South Africa did not occupy German South-West Africa, Britain was ready to send in Australian (or worse, Indian) troops to do the job for them. That, he warned, would be in the nation’s worst interests, as it would both tarnish South Africa’s image among the Allies, especially if troops of colour showed them up, and be a lost opportunity for South Africa’s grand designs on the subcontinent.

Among the hundreds of volunteers eager to fight under the wily general was Deneys Reitz. Being from the Free State, where republican feelings ran deepest, Reitz’s decision went against the grain. Most volunteers came from former British territories within the Union – the Cape and Natal provinces – as well as Botha’s own sphere of influence, in the eastern and central Transvaal, where he enjoyed unprecedented Afrikaner support. The western Transvaal, where De la Rey was idolised, and the Orange Free State, from where De Wet hailed, were an entirely different matter.

What made Reitz different? During his self-imposed exile in Madagascar following the Boer War, the young Reitz contracted malaria. On his return to South Africa, he spent a lengthy convalescence in the Smuts household. During this period, he came to understand Botha’s policy of reconciliation and the importance of Britain in the Union’s future. Over time, Reitz, like Smuts, became a loyal Botha supporter, even though his fellow Free Staters held a different opinion.

De Wet publicly berated Reitz for supporting Botha when the two met on the streets of Reitz’s hometown, Heilbron, where De Wet was vociferously campaigning against Botha’s decision to invade.1 Reitz’s father, Francis William Reitz, was a former Free State president and a republican. When hostilities broke out, Reitz senior was president of the senate in Parliament. Although against the invasion, as a parliamentarian he preferred resistance through that democratic medium rather than armed protest. De Wet, being the rabble-rouser he was, accused the younger Reitz of not only turning his back on his country, but his republican heritage as well.

By the end of September 1914, Reitz could sense the growing militancy in the Free State.2 Despite assuring Botha that protests would be peaceful, De Wet was rushing about advocating armed resistance, and thousands of Free Staters were heeding his call. Beyers was apparently doing the same in the western Transvaal, but the prime minister was not overly concerned. It was tradition among Afrikaners to voice their displeasure through ‘armed’ protest. Sabre-rattling was the way the old Boers let off steam and settled their disputes. Besides, Botha remained in close and constant contact with Beyers, De Wet and Kemp, and he knew they had no real intention of firing upon their own brethren. A full insurrection was simply out of the question.

That was until the hulking Manie Maritz waded into the fray. With his replacement, Coen Brits, en route to Upington after the Sandfontein fiasco, Maritz effectively abandoned the Union Defence Force and moved all his forces to Kakamas to be closer to the German border. In early October he made overtures to von Heydebreck, expressing a desire to join forces with South Africa’s enemy. The German commander was somewhat mystified by Maritz’s wish to switch allegiances.3 He was no doubt aware of the anti-invasion sentiment in the Union, but to what extent it would manifest in armed rebellion was, at that stage, still unclear, and von Heydebreck did not want to get mired in the confusion that was South African politics. His mandate was simply to defend the colony, not to go on the offensive in foreign territory.

Militarily, a sound defence was the right thing to do. It was far safer and easier to defend than to stretch his dangerously meagre resources on an offensive, as the South Africans themselves had discovered to their peril at Sandfontein. In any case, von Heydebreck thought Maritz too much of a loose cannon. The German commander correctly assumed Maritz was liable to be more of a hindrance than a help to the German cause.

The veggeneraal, however, was determined to go over to the Germans. At a parade for his troops, he vilified the South African government in a fiery, if somewhat incoherent, rant and gave his men one minute to decide whether or not they were with him in throwing in their lot with the Germans.4 Most of the impressionable young men accepted, but fifty, including Reitz’s brother Joubert, refused and were stripped of their weapons and horses and unceremoniously marched across the border as prisoners of war.5 Maritz then promoted himself to the rank of general, raised the old Transvaal republican flag, the Vierkleur, and declared war on Britain. These eccentric antics would have been dismissed by the South African government had Maritz not also implicated Beyers, Kemp and De Wet in his act of treason.6

In truth, the three had nothing to do with the trouble-maker stuck away in a distant outpost on the Orange River, but Maritz’s claims prompted Smuts, as minister of defence, to declare nationwide martial law. De Wet interpreted Smuts’s action as an open threat of armed suppression of all republicans. Furthermore, martial law meant that defence-force recruitment changed from volunteerism to full conscription. It forced the Free State and Transvaal republicans to openly decide on whose side in the war they stood.7

On 19 October, despite misgivings of prematurity, De Wet, Beyers and Kemp called for republicans to ignore the declaration and consider full rebellion. The response was immediate. Thousands of young men saddled up to ride for the rebel cause, eager to fight with the famous Boer War generals.8 Those Afrikaner republicans already attached to the Union Defence Force prudently resigned their posts. The stalwart generals were now determined to unseat Botha and declare a South African republic, with the Free Stater Hertzog as their president.

Hertzog, however, was keeping uncharacteristically quiet. He voiced neither his support nor his opposition for the republican cause. He preferred to channel his political will peacefully, though vociferously, through Parliament. It was blatantly obvious that the fiery orator was sitting on the fence, possibly awaiting the outcome of the rebellion before he pinned his colours to the mast.

On 26 October, the rebellion was officially proclaimed. The South African public, and the Germans across the border, held their breath as the rebels fanned out from their strongholds in the Free State and Transvaal. Within days, almost the whole of the Orange Free State was under rebel control. Loyalists like Reitz just managed to escape with their lives. He and a handful of others made their way to Pretoria where they learnt that Beyers and Kemp had taken control of large tracts of the western and northern Transvaal.

Maritz, however, was faring badly. Having foisted himself on the Germans, they diffidently bolstered his force with artillery and weapons, but von Heydebreck refused to go further to support the rebel cause and held back on lending Maritz any of his own soldiers, a move that Botha undoubtedly would have regarded as an act of aggression.

Undeterred, Maritz returned to the Union to face government loyalists who had moved opposite him on the river. The loyalists promptly routed his forces and the rebels had to scurry back across the border, to the obvious misgivings of the German command. Maritz realised he was too isolated geographically from the main theatre of the rebellion to be effective, and with loyalists solidly barring the way, there was no hope of linking up with the rebel forces in the Free State and Transvaal.

Despite their initial successes, the rebels were no match for Botha. He had confidently rejected Britain’s offer to supply detachments of Australian troops, cleverly ensuring that his loyalist ranks were made up mainly of Afrikaners. He did not want to strengthen the republican cause by deploying too many English-speaking troops. On 26 October, Botha took to the field accompanied by his bodyguard, which had been formed earlier in the year by Major H.F. Trew, head of the police force in Pretoria, after an assassination plot that implicated Beyers. Although Botha had initially ridiculed the idea of a personal bodyguard, he had since taken a keen interest in it, and it soon became a highly trained crack commando.9

Lieutenant Eric Moore-Ritchie, one of the policemen who had eagerly signed up to Botha’s elite bodyguard, records that they first headed west for Rustenburg, where Beyers and Kemp had established the headquarters of the Transvaal rebels. Within a couple of days, surprised at the speed of Botha’s manoeuvring, both commanders and their men were on the run. They evaded capture, but neither commanded an effective fighting force any longer. As in the Boer War, the two leaders separated and retreated into the hills, resorting to guerrilla tactics.10

In the meantime, Botha returned to Pretoria. He was well accustomed to guerrilla warfare and his men were equally adept at mopping up the scattered units. They successfully divided and isolated the small rebel commandos, and only a few skirmishes followed, including a couple of sharp ones against Major Jopie Fourie, a Union Defence Force officer in charge of a commando that was doggedly resisting capture. It is said that Fourie’s band was responsible for a third of the loyalist casualties in the Transvaal, although they were largely ineffective in the broader scheme of the rebellion and simply prolonged the inevitable. Botha’s bodyguard eventually captured Fourie in December. As he had neglected to resign his defence-force post before changing sides, he was the only rebel to be executed.

On 9 November, Botha turned his attention to the Orange Free State and De Wet. The cantankerous old general had a large force of over 5 000 rebels. On 12 November – incidentally, the same day von Heydebreck was unexpectedly killed in South-West Africa when an experimental grenade launcher he was testing misfired – the prime minister and his forces arrived at the central Free State town of Winburg, which De Wet had vacated the day before. Hoping to obtain intelligence on De Wet’s route out of Winburg, Botha resolved to telephone Smuts at headquarters in Pretoria. As he was about to pick up the receiver at the local post office, the phone rang. An orderly answered and a whispered voice on the other end told him that they were being held prisoner by De Wet on a farm called Mushroom Valley, a day’s march south of Winburg. De Wet had encamped with his entire force on the farm for the night and had locked some hostages in a room, failing to notice the telephone in the room or to cut the telephone lines outside.11 It is rumoured that at the probable time of the call, De Wet himself was casually leaning against a telephone pole smoking a pipe.

True to form, Botha wasted no time. He immediately got in touch via heliograph with Brits, who, after ensuring Maritz’s permanent immobility, had, together with Lukin (then at Steinkopf), raced east to assist the commander-in-chief against the greater threat of the Free State rebels. Botha instructed the two generals to converge on the farm by securing his right flank so as to prevent any possible escapes when he attacked. Even though it was by now nightfall, Botha ordered his forces to mount up. His aim was to surprise De Wet at sunrise. It was not an unexpected move. As Moore-Ritchie notes, ‘General Botha is celebrated amongst fighting men for many things … his night marching is one of them.’

It was a taxing sixty-four-kilometre ride in pitch darkness and freezing temperatures. Moore-Ritchie continues:

During the all-night trek from Winburg to Mushroom Valley I had a first thorough experience of the true horrors of sleep-fighting. It was bitterly cold as the Free State night on the veld knows how to be. And we could not smoke, could not talk above a faint murmur, and nodded in our saddles. The clear stars danced fantastically in the sky ahead of us, and the ground seemed to be falling away from us into vast hollows, then rising to our horses’ noses ready to smash into us like an impalpable wall. After midnight, outspanning in a piercing wind, we formed [a] square; main guard was posted over the General’s car, and those lucky enough to escape turn of duty huddled together under cloaks and dozed fitfully until two-thirty. From two-thirty till sunrise we trekked on.12

At dawn the fruits of the forced march were revealed. Botha’s column was on top of the unsuspecting rebels, who had not even posted sentries. They were literally caught napping. Botha brought up the artillery and opened fire on the sleeping camp. He then advanced and after two hours of fierce fighting the action was over, with Botha the victor.

But De Wet had escaped, thanks to Brits and Lukin who had been quarrelling during the night march and as a result mistimed their advance, leaving a gap for the old general and a few followers to get through.13 Yet, like Beyers and Kemp, De Wet was now just another fugitive with no army to command. He had abandoned most of his men at Mushroom Valley, along with his transport wagons with all his ammunition and supplies. Twenty-two rebels lay dead and the rest were taken prisoner. It was a resounding, although bittersweet, victory for Botha. It pained him to see so many of his old friends and comrades lying dead or wounded. ‘Life,’ wrote Moore-Ritchie of his leader’s sombre mood after the battle, ‘was not dealing too fairly by him.’14

After Mushroom Valley, Botha concentrated on mopping up the last pockets of resistance throughout the province. Beyers and Kemp were by now in the field somewhere in the Free State, but after De Wet’s defeat the cause was lost. Loyalist troops occupied the towns one by one, the citizens surprised by their Boer composition. Reitz records an incident in which an old Free State woman rushed to view the triumphant loyalist army and, on seeing only Afrikaners, shouted, ‘Waar is die verdomde Engelse?’ Where are the bloody English? To which a young scout replied, in Afrikaans, ‘Old lady, we are the bloody English.’15

On 1 December, De Wet, exhausted and broken, was captured on the fringes of the Kalahari just across the border in British Bechuanaland. Brits had commandeered a number of motor cars and gone after him. Tired from the relentless pursuit and mourning the loss of his son who had been killed just days before the defeat at Mushroom Valley, De Wet’s prodigious fighting spirit was finally extinguished. And so the glittering career of the shrewd general, who had never been defeated by the British, suffered an ignominious end at the hands of his own people. ‘At least the English never captured me,’ he said as he handed over his pistol to Brits’s men.16

Of the capture, Reitz notes with some sadness that the use of mechanised vehicles ‘spelt the end of the picturesque South African commando system’.17

Beyers, in the meantime, was trapped in the northern Free State. Seven days after De Wet’s capture, and hemmed in on all sides, he tried to swim with his horse across the flooded Vaal River. It was the last time anyone saw him alive; both man and beast drowned in the attempt. This left only Kemp, with a small band of men and horses, in the field. With Botha’s men pursuing him relentlessly, he made a heroic dash across the Kalahari in order to link up with Maritz, who was waiting sedately in the German colony. The rebels, struggling over dunes and stony ground, fought a continuous rearguard for what must have seemed like an eternity. They finally staggered across the border near present-day Nakop with government forces snapping at their heels. The Germans welcomed the exhausted men with some trepidation. The rebellion, in spite of providing a short respite for the German forces, had not worked in their favour.

By Christmas, Botha had cleaned up the Free State and Transvaal. Most of the rebel ringleaders were either dead or imprisoned, and the prime minister was happy enough with the state of affairs to take a well-earned holiday on his family farm in the eastern Transvaal. Just before Christmas, Maritz and a recuperated Kemp tried to launch a hare-brained surprise attack on Upington, where Brigadier General Jaap van Deventer had taken over from Brits earlier in the month.

Jacob Louis van Deventer, or Jaap as he preferred to be called, was a colourful, tough-as-nails and larger-than-life Boer commander, both in character and physique. He was a giant of a man, standing almost two metres tall, and an expert practitioner of commando tactics. As with most of his contemporaries, Van Deventer had served in the Boer War, first under De la Rey, then Beyers, and finally with Smuts and Reitz in the northern Cape. It is said that he was present when the first and last shots were fired, but was seriously wounded towards the end of the war. Reitz found him ‘huddled on the ground before his horse … Blood was pouring from a bullet wound in his throat, and his tongue was so lacerated that he could not speak.’18 For the remainder of his life, Van Deventer spoke with a stifled rasp as a result of his injury, and he commanded the utmost respect from almost all who met him.

Maritz and Kemp’s last-ditch effort to attack Upington failed dismally in the face of the increased numbers of Van Deventer’s government forces mustered along the river and a personality clash between the two rebel commanders. The calm Kemp refused to serve under the bellicose Maritz, who insisted on making himself supreme commander of the rebel forces. Nonetheless, they tried again a month later, on 24 January 1915. This time their forces were bolstered by German Schütztruppe and the Burenvreikorps, a group of irregular militia consisting exclusively of Boer War veterans who had fled South Africa to the German colony in 1902 and had settled on cattle farms along the Nossob and Auob rivers in the south-east.

The Germans’ eventual entry to the rebellion is somewhat puzzling. It was against both the late von Heydebreck’s sound advice and Germany’s mandate. As Major von Rappard, von Heydebreck’s like-minded second in command, had been killed at Sandfontein and the next most experienced officer, Major Franke, was on a mission against the Portuguese in the far north (see Chapter 5), the local German command in the south was handed to the inexperienced Major Hermann Ritter. Ritter, for reasons known only to himself, decided to throw all caution to the wind and join with Maritz and Kemp to attack the Union.

He supplied the rebels with four light field guns, a Pom-Pom gun and a company of mounted riflemen. The idea was to launch his own mounted column of 400 men with four artillery guns on Steinkopf. Taken in isolation this was not a bad move, since Steinkopf had been evacuated during the rebellion and only a small detachment of the Witwatersrand Rifles Regiment was left to guard it.19 However, in the bigger scheme of things it was of little value. Steinkopf by then had been jettisoned by the South African supreme command as a launch pad to invade the colony, and the railhead’s isolation would have little served the German cause. As it happened, Maritz and Kemp once again failed at Upington (they were successfully repelled by Van Deventer), prompting Ritter to redirect his attack in order to divert the South African forces away from the disorganised rebels. He turned his attention instead on the town nearest his position, Kakamas, more for want of something to attack than anything else.

As usual for forces operating in this sector, Ritter’s most immediate hurdle was his stretched lines of communication, one of the reasons von Heydebreck had refrained from such a move. In diverting their attack from Steinkopf to Kakamas, Ritter and his men had to pass through country devoid of water and fodder, a problem made even worse by the fact that there had been no time to organise supplies before they left. Nakop, on the border, had a well, which they reached on 1 February, but since the rebels had passed through a week earlier there was not enough water left for all the horses to satiate their thirst. Ritter was forced to move on to another watering point on the Molopo River, about fifty kilometres into Union territory.20 It was the first and last time South Africa was invaded. Technically it was not an invasion – it was more of an incursion – but nonetheless Ritter holds the accolade of being the only enemy commander to take a regular force of soldiers into South Africa.

Whatever it was, it was unsuccessful. The water situation at Molopo was the same as at Nakop, and the tired and thirsty mounts were pushed further south towards the Orange River. By this time all excess baggage had been sent back to lighten the load of the thirsty beasts, but it meant the soldiers were on severe rations, too.21

Before reaching the river, Ritter and his men captured an oxwagon and its Baster driver. The Basters are the descendants of Cape Colony Dutch and indigenous African women, and live largely in and around the town of Rehoboth. The man told them there were two ferries on the river at Kakamas, a kilometre apart. He also maintained that there was an exposed enemy encampment on their side of the river. Based on this information, Ritter split his meagre force into two columns. First Lieutenant Friedrich von Hadeln was to take a division directly to Kakamas to attack the enemy contingent and secure the ferry downriver, while Ritter and the others encircled to the east as the left flank to take control of the ferry stationed upriver before attacking the enemy on its flank and rear.

The columns eventually reached the Orange River on 4 February, having covered a staggering 175 kilometres from their base at Warmbad in a week, and realised they had been misinformed. As Lukin had previously discovered, the local man was more concerned with providing intelligence that would please his interlocutors than conveying actual facts. While there were indeed two ferries, they were in fact five kilometres apart. And the exposed enemy encampment was in reality well entrenched with artillery and on the other side of the river. Since the ferries were much further apart than expected, contact between the two columns was lost, and, as the enemy was on the far bank of the river, the element of surprise and encirclement was mitigated, rendering a coordinated attack impossible.22

Kakamas itself lay on the south side of the river and consisted of isolated houses surrounded by gardens, spread along the riverbank for a number of kilometres. Ritter decided that crossing the river was pointless because any enemy reinforcements arriving from Upington along the north bank would cut off their retreat. Instead, he ordered his artillery to fire on the houses and the few enemy soldiers in the vicinity. Damage was limited, although there were a few South African casualties. Ritter then sent a company to find von Hadeln’s column, but they came under fire from some South Africans who had crossed the river, and were forced to retreat after losing an officer and three men.23

Major Ritter’s abortive incursion into the Union. It was the first and last time South Africa as a nation was ‘invaded’

By now Ritter had received a message that von Hadeln required artillery support. He had come under fire from a strong South African contingent occupying the heights across the river and had become pinned down. Von Hadeln was well aware that his unit would be massacred if they tried to withdraw without artillery support to cover their retreat. Ritter, though, was now panicked by the prospect of the main South African force swooping down from Upington and refused to lend von Hadeln the support he requested. Instead, Ritter hastily retreated back from the river through a narrow pass, leaving his first lieutenant to his fate.

Against all odds, von Hadeln managed to safely extricate himself and his men, but he was unable to properly water his horses before moving away from the river. As a result, most of the mounts died on the return journey, during which the South Africans continually harassed their rear. Wrote one soldier of the pursuing commandos: ‘Their marksmanship, even at far distances, was good, resulting in heavy losses of horses and mules.’24

Von Hadeln apparently won an Iron Cross for his leadership, yet the whole escapade had been fruitless. By the time they reached German territory, the Schütztruppe had lost seven men, with six wounded and sixteen captured. Another dejected trooper summed up the raid: ‘We had achieved … nothing.’25

While the Germans retreated across the desert, Kemp, who was somewhere near Upington, was desperately ill, as well as dispirited. He had always known that without Beyers or De Wet the rebel cause was lost. On 4 February 1915, he meekly surrendered to his opposite number, Jaap van Deventer, as did most of the rank-and-file rebels. While the leaders were imprisoned, many of their men immediately switched sides and joined Van Deventer’s commandos. He welcomed them into the fold, but only after first getting permission from Botha.

De Wet and Kemp were given relatively light sentences. They were imprisoned for the remainder of the war and then released. Maritz, however, scurried back across the border to evade capture, but the Germans wanted nothing more to do with him. He spent the remainder of the war in Portuguese West Africa and then lived in exile, first in Portugal and then in Spain.

It is estimated that about 13 000 South African men took up arms in the rebellion.26 The uprising left Botha deeply shaken. His long preoccupation with reconciling English- and Afrikaans-speaking South Africans had led to an irreparable split in Afrikanerdom. He desperately tried to patch things up in the aftermath, but for most republicans his gestures were too little too late. The rebellion left a lasting bitterness among Afrikaners and was to have profound consequences for their collective psyche.