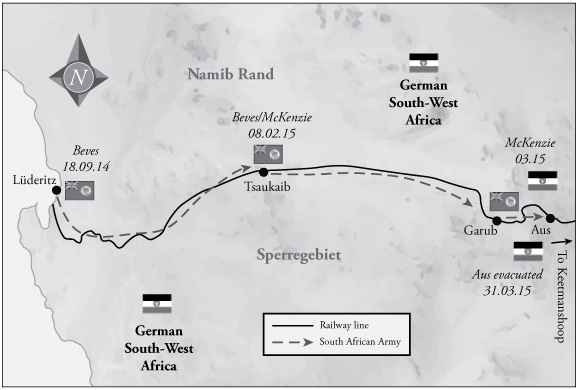

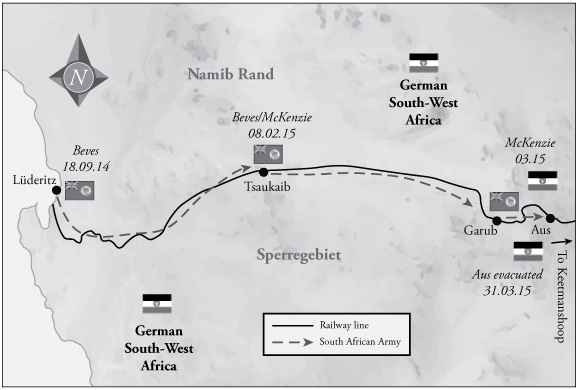

What began as B Force under Colonel Beves became Central Force under General McKenzie. It was tasked with painstakingly advancing 120 kilometres across the desert from Lüderitz to the German-held positions at Aus

6

Central Force

WHILE THE REBELLION raged across their home country, for an interminable five months Colonel Beves and C Force moved steadily into the desert from the rocky, windswept port of Lüderitz, doggedly sticking to their task. With the withdrawal of Forces A and B in the south and the subsequent rebellion, C was the only force now facing the Germans. Inch by inch they made their way into the hinterland following the railway embankment west towards Aus, re-laying the line destroyed by the Germans as they went.

From November to January C Force’s progress was hampered by the three German airmen in their rickety flying machines taking off from a new base at Aus. They began by dropping pro-rebellion propaganda pamphlets onto the troops below, but when this proved inconsequential (the force consisted primarily of English-speaking South Africans from units of the former British colony of Natal), the pilots decided to drop something a little more persuasive.1

It was the civilian pilot Willy Trück who designed the aircrafts’ crude but effective bombs. Made from refashioned ten-centimetre artillery shells, they each weighed about thirteen kilograms. Linen tails were attached to the bombs to enable them to fall nose down. To carry them, two metal tubes with lids fastened on the front end were fitted to the sides of the aircraft. As the pilots approached the target, they would nosedive and open the lids by pulling a string, whereupon the bombs would slide out and zigzag down to earth. The bombs, however, had one serious drawback for the pilots: they were always live. If the aircraft had to make an emergency or even a bumpy landing, the bombs could easily detonate. Every time the pilots climbed into the cockpits of their flimsy aeroplanes they were therefore risking their lives. It is a great wonder that all three managed to survive the campaign despite numerous crashes.

Initially, the German airmen had only marginal success with their bombs. They did, however, manage to kill the odd soldier and horse in return for some bullet holes in their fuselages.

C Force reached the station and water well at Tsaukaib, roughly halfway to their destination, in February 1915, as the rebellion was being brought to an end. There they were joined by their new commander-in-chief, Prime Minister Botha, and Beves’s direct superior officer, Brigadier General Sir Duncan McKenzie. It was time to resume the invasion.

Botha began by radically altering the strategy. He scrapped the three-prong approach in the south in favour of a broader four-prong attack on Windhoek, adding a main thrust from Walvis Bay/Swakopmund in the north, which Botha himself would lead. This new prong, called Northern Force, consisted of three mounted brigades, two artillery batteries, two infantry brigades, two unbrigaded battalions and one mounted regiment.

To ensure Swakopmund was still unoccupied, Botha had sent up an advance force from Cape Town in December. The advance was led by the imperiously named Colonel Percy Cyriac Brunnel Skinner, who was on loan from the British Army and tasked with setting up the general staff for Botha’s Northern Force. Collyer describes him as ‘a keen soldier of considerable nervous energy’, who ‘was well versed in his profession’.2 Under Skinner’s command, the force had entered the unoccupied town without resistance in the first days of January 1915 and begun preparations for the arrival of the main body of troops scheduled for a month later.

In Tsaukaib, McKenzie replaced Beves and C Force was renamed Central Force. McKenzie, with two mounted brigades and two batteries of field guns, was to abandon the ponderous process of rebuilding the railway line from Lüderitz and instead ride hard across the desert from Tsaukaib to attack the well-entrenched German positions at Aus.

The reconfigured southern attack was to continue under Brigadier General Jaap van Deventer, who was already advancing from Upington with twenty-nine mounted commandos and one battery of field guns. He was instructed to divide his men into five columns, which collectively would form Southern Force.

Lieutenant Colonel Berrangé was put in charge of the 1 200 mounted rifles and one 12-pounder quick-firing field gun that made up Eastern Force. He was to make a near-impossible crossing of the Kalahari from the distant mission town of Kuruman in the east and enter the German territory at the Baster border hamlet of Rietfontein. Preparations for the desert crossing had begun in December already, presumably originally under Smuts’s orders. Berrangé was to converge with Van Deventer at Keetmanshoop, and then together thrust north up the railway line towards Windhoek.

The Central, Southern and Eastern forces were essentially designed as a ruse to split the Germans while Northern Force rapidly advanced into the heart of the German colony to Windhoek, where they would destroy the wireless tower as instructed by the Committee of Imperial Defence subcommittee.3

Botha hoped that by keeping the Schütztruppe occupied in the south of the colony, he would dupe Franke, who, following in von Heydebreck’s footsteps, remained convinced that a South African invasion could only be achieved from across the Orange River. Collyer notes that, if successful, Botha’s multi-prong attack would effectively deny the German command their ability to rapidly concentrate their forces on a single enemy.4

If Botha were to occupy the capital, even if the German forces remained in the field, he would have achieved all three objectives set out by the imperial subcommittee. The fact that, with the radio tower in Togoland already out of action and the ports of Swakopmund, Lüderitz and Walvis Bay in South African control, the radio mast in Windhoek was essentially a lame duck did not deter him. He wanted to ensure that the objectives were met to the letter. And he wanted nothing less than a complete German surrender, an essential prerequisite if his plans to incorporate the German territory into the Union were to succeed. The southern diversion was pure genius in its simplicity and typical of Botha in execution.

His scheme was not without serious obstacles, however. The communication and supply lines that had hampered the previous plan of attack under Smuts were still a problem, now even more so given the additional front and increased manpower. The number of South Africans had quadrupled to nearly 13 000 in the wake of the rebellion and now outnumbered the German soldiers two to one.

Of greater concern to Botha was the rapidly rising cost of the campaign. What began as a simple expeditionary mission had, thanks to the Sandfontein reversal, turned into a nationwide mobilisation for a full-scale invasion. Botha knew that the longer the burgeoning South African force was in the field, the higher the national cost. As prime minister he knew he could not plunder the Union’s coffers indefinitely, especially since Hertzog had found his voice and was complaining in Parliament about the heavy burden the campaign was placing on South African taxpayers. It was therefore essential that Botha got the job done quickly. Events were already unfolding too slowly for his liking and, ironically, the biggest drag on his plan for rapid deployment was the very man tasked with speeding things along.

Sir ‘Dunc’ McKenzie was the beloved commander-in-chief of the former colony of Natal.5 Born in Africa but with hardy Scottish heritage, McKenzie was tough, gritty and dependable, well suited to the life of a colonial soldier in nineteenth-century Natal. A pioneer, hunter, consummate horseman and one-time transport rider, he spoke fluent Zulu and served in a number of minor campaigns to put down native uprisings before the Anglo-Boer War.

During the war he served with distinction in the Natal Carbineers, the only mounted British unit in the field not besieged at Ladysmith,6 and later in the Imperial Light Horse. It was said that due to his ability to move rapidly and his willingness to take risks – skills he had learnt as a transport rider – McKenzie was the only officer to have come close to capturing the elusive General de Wet,7 and he probably would have were it not for the dithering of his commanding officer. McKenzie was arrested on that occasion for venting his anger and using colourful Caledonian language in front of his astonished superior. A young Winston Churchill was met with the same colourful language when, as a news reporter, he timidly asked McKenzie for leave to break into Ladysmith to interview the besieged commander there. It was an action, McKenzie argued between oaths, that would unnecessarily endanger soldiers’ lives. Churchill in any event ignored the irascible McKenzie, to his own peril. Quite a few lives were endangered and the act led directly to Churchill’s much-publicised capture and imprisonment, which, incidentally, was effected by Botha’s own commando operating near Colenso in November 1899.8

McKenzie found real fame, or rather infamy, during the 1906 Bambatha Rebellion. Bambatha kaMancinza was a Zulu chieftain whose tribe lived in the Mpanza Valley near Greytown, coincidentally the birthplace of Louis Botha. Chief Bambatha, fed up with paying onerous taxes to the British colonial government, one day refused to pay any more. A pair of debt collectors was sent to recover the overdue funds, but they were murdered by some of Bambatha’s overzealous followers, prompting the Natal government to declare martial law. In response, the chief took up arms against the government. As commander of the colonial forces in Natal, McKenzie took a battery of howitzers and artillery and went to quell the insurrection. On 10 June 1906, he entrapped the rebels, who were armed only with spears, in a deep, wooded valley called Mome Gorge. The soldiers opened fire and massacred over 3 000 Zulus, including Bambatha, whose head was lopped off and put on a spike and paraded in front of the few survivors.

For his efforts, McKenzie received the adulation of the white colonialists, a knighthood from King Edward VII and, until recently, his name on a major thoroughfare in Pietermaritzburg, the one-time capital of Natal. King Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo, Bambatha’s king and Botha’s old friend and comrade, was imprisoned for tacitly backing his chieftain’s rebelliousness, and was released four years later when Botha became prime minister of the new Union of South Africa. It is probable that Botha disliked McKenzie for the latter’s treatment of Dinuzulu’s kinsmen, but, owing to his preoccupation with reconciliation, Botha must have found it necessary to appoint a renowned English-speaking soldier like McKenzie to relieve Beves at Lüderitz.

On 8 February 1915, before leaving for Walvis Bay, Botha held a brief war council with McKenzie. With Central Force now considerably reinforced, Botha wanted the general to live up to his reputation as a rapidly mobile commander and launch the quick-fire attack on Aus with immediate effect. It was a big ask, even for a man like McKenzie. Any functional railway terminated at Tsaukaib and there was still about sixty kilometres between there and Aus.9

Uncharacteristically, McKenzie baulked.

Tsaukaib is just outside of the coastal dune belt that separates Lüderitz from the world. From here one is able to look due east across the featureless desert plain all the way to the imposing wall of ochre mountains where the village of Aus nestles in its impregnable position behind the ridge. Besides a sign along the railway line, there is nothing at Tsaukaib today. Now that steam engines belong to a bygone age, trains no longer have any reason to stop here. The foundations of the old train station are still visible, but there is no evidence of the well that once supplied the trains or of McKenzie’s men who mustered here a hundred years ago. One can see how the prospect of crossing sixty kilometres of open desert on horseback without water or cover to attempt an assault on an entrenched German position behind a range of mountains must have alarmed the general. In facing such impossible odds, he must have felt the ghost of Chief Bambatha had come to return the favour.

About forty kilometres from Tsaukaib, just before the mountain range, the flat desert plain dips a little. Here, in a gigantic grassy bowl, was the train station of Garub and another well, the only other watering hole before Aus. Besides its good grazing, Garub was strategic as it was near enough to Aus to stage a final assault, yet far enough away from the fortified German position to be out of reach of any potential long-range shells. As far as McKenzie was concerned, their only hope of occupying the impregnable Aus lay in using the element of surprise. He thus proposed an all-night march from Tsaukaib to a place about ten kilometres shy of Garub. At dawn the infantry would advance to secure the well, while the mounted troops would continue on directly to Aus. This plan, McKenzie reasoned, had the greatest chance of surprising the enemy.

Botha disagreed. Besides the danger in splitting the troops, there was the obvious disadvantage of the infantry having to march a further ten kilometres to Garub in daylight and be exposed to a full attack on the back of an all-night march. Furthermore, if the Germans were prepared to hold Garub they might have machine-gun units sweeping the open ground. And in any case, Botha argued, the mounted men attacking Aus still had thirty kilometres of open plain to cross and would be spotted long before they made any significant ground, giving the German artillery gunners plenty of time to respond. Surprise was not possible.

What began as B Force under Colonel Beves became Central Force under General McKenzie. It was tasked with painstakingly advancing 120 kilometres across the desert from Lüderitz to the German-held positions at Aus

Botha thought it best to march through the night all the way to Garub and take it before dawn. This plan would give them more chance of securing the all-important well; a necessary, if not vital, manoeuvre after the long slog from Tsaukaib. Taking Garub first would also increase the morale of both men and horses. With its ample grazing and water, it would offer a welcome rest on their long march east.

Having thus re-laid the plan, Botha returned to Lüderitz and by evening was aboard a troop ship steaming towards Walvis Bay, where he arrived the following morning.10

McKenzie, following Botha’s revised orders, moved directly to Garub and occupied it easily, despite the fact that by now the German pilots had honed their skills to the point where they were able to drop their incendiaries with greater precision onto the Allied troops below. The German patrols at Garub preferred to retire rather than risk unnecessary loss of life and equipment. If men were killed, wounded or captured, and equipment destroyed or taken, they could not be replaced until the blockade on the ports had ended. The Germans thought it prudent, therefore, to conserve men and weapons rather than risk losing both. Before leaving, however, they poisoned the well.

Botha had planned to time his own advance on the German lines that had formed along the dune belt outside Swakopmund with McKenzie’s attack on Aus, thus preventing any possibility of the Germans redeploying men to Northern Force’s theatre of operations as they had against Grant at Sandfontein.

But McKenzie hesitated at Garub, despite Botha’s urgent appeals to keep moving. They had to dig a new well, his full force had only recently encamped and the new arrivals, having run the waterless gauntlet from Tsaukaib to Garub, were in no condition to advance. Central Force was not ready to attack, McKenzie bluntly stated in a telegram to Botha in early March.11 The restless prime minister would have to advance without a diversion from them.

In desperation, Botha pressed Smuts to wrap up the parliamentary session in Cape Town and make haste to Lüderitz to take overall command of Central Force and amalgamate it with Van Deventer’s force in the south and Berrangé’s force in the east. After a further two weeks of delay, Botha, who was by then making significant gains in his sector and could no longer wait for Smuts, abandoned his men on the front line and rushed back to Lüderitz in an effort to spark the obstinate General McKenzie into action.

In the meantime, the German aircraft based at Aus continued to harass Central Force. By now von Scheele had been recalled to fight Botha’s force in the north, and the main targets for the two remaining German pilots were the poor horses corralled at Garub. Once released, the bombs took a full twelve seconds to hit the ground. That usually gave the men below time to take evasive action, but not the penned-in horses. As with Sandfontein, killing the mounts was a strategic objective, the aim of which was to delay any advance. On 23 and 27 March, Fiedler and Trück bombed the corral housing McKenzie’s 1 700 horses.12 While only a few died in both attacks, the remaining horses on the 27th stampeded, broke loose and galloped off into the desert. Enough were rounded up and returned in time to carry out Botha’s latest stern directive to march on Aus, but many were never recovered.

Finally, on 31 March, a nervous McKenzie gave the order to attack. Their advance was hampered somewhat as the Germans had randomly mined the roads and paths leading up to Aus. But they eventually reached their target … only to find that Aus had been abandoned.13 As Botha had feared, his thrust in the northern sector had prompted the undermanned Schütztruppe there to recall all available resources. Aus was deemed too isolated to defend and the garrison had made the smart choice to retreat.

Major Franke had initially fallen for Botha’s feint, assuming incorrectly that the main South African attack would come from the south. But when Botha began to storm inland from Swakopmund in mid-March, Franke realised his mistake and ordered all personnel facing McKenzie, Van Deventer and Berrangé in the south to abandon their forward positions and fall back along the railway lines to bolster the forces facing Botha without delay. From there they were to gather all troops, horses, weapons and artillery and fall back in an orderly fashion towards Windhoek. Von Heydebreck had devised this emergency plan before the war in the event that the forward defences were ever breached or threatened. The retreat was ostensibly a good idea, as the Germans were effectively retiring onto their own supplies and ought to have been capable of defending the north and south of the capital. In the south, where the railway passed through the town of Rehoboth, the Germans could once again form a strong defensive position, as here the endless plain from Mariëntal suddenly rises into another set of imposing mountains.

The command to retreat from Aus was effected by Major von Kleist, the German officer in charge of the southern forces and seemingly no relation to Paul von Kleist, who encircled the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk in 1940, or Ewald von Kleist, who was implicated in masterminding the Hitler bomb plot in 1944. This von Kleist pulled back from Aus just before McKenzie attacked and was thus able to make good his escape with all his personnel, artillery and the two aeroplanes.

It is easy for historians to blame McKenzie for his uncharacteristic inactivity, but in truth he was facing insurmountable odds against an impregnable mountain position. If the Germans had not timeously pulled back, Central Force could have suffered severe casualties. The Germans enjoyed an extremely powerful defensive position at Aus, one that also allowed them the luxury of carrying out various attacking raids on the South African forces concentrated in the grassy valley below. This made life extremely uncomfortable for McKenzie and his men. And although Garub was too far for long-range artillery, for the first time in their military history, the South Africans were met with attacks from the air, something with which they had no prior experience.

These days the landscape around Garub is exactly as it was a hundred years ago. Driving into the bowl-like plain from the direction of Lüderitz, the first thing one notices is the unusual presence of yellow grass, after the seemingly interminable naked dunes. But before one has time to reflect on the sudden change in vegetation, the eyes are drawn to the dozens of grazing horses. Garub’s desert horses have become something of a tourist attraction.

Most tourist brochures refer to the Garub horses as ‘wild’ – even the road sign announces ‘Garub Wild Horses’. This is not technically correct. The only wild horses in Africa are zebras. These are feral. The same brochures state that no one really knows where the horses came from. Some guidebooks speculate that they escaped from a ranch – not that there are, or were, any nearby. Others say they may be survivors of one of the numerous shipwrecks, but Garub is too far away from the coast, separated from it by inhospitable land. The horses would have met certain death if they had ventured inland. Ditto for the theory that they are escaped draft horses from the old diamond works at Kolmanskop, a coastal ghost town just outside Lüderitz.

The most plausible explanation for the presence of these horses is the war that was fought here and, more specifically, the two German bombing raids on the South African corral in March 1915. It was natural instinct that made the terrified horses bolt into the desert. One could be forgiven for thinking it was certain death for any animals lost in that harsh environment. Deneys Reitz certainly came to that conclusion.

One morning, Reitz, who arrived in Aus just after it was occupied, rode up from the railhead, which by that stage had reached Garub. He was on his magnificent black thoroughbred called Bismarck, one of the best-bred horses in South Africa, or so Reitz claimed. At some point they came upon an infantry column of reinforcements marching to Aus. Reitz relates what happened when one of the men stepped on a German mine:

I rode chatting to the officer at their head when suddenly there was a roar in the midst of the soldiers and a column of smoke and dust shot a mile high, whilst fragments of metal went whizzing in all directions. When the air cleared, two men lay dead and a dozen wounded, and many others were temporarily blinded by the spurting sand. My horse, stung by flying grit and pebbles, reared and plunged, and when I dismounted to help the injured, he gave a snort of terror and, wrenching free, headed straight for the waterless desert … By the time we had made the wounded men comfortable and I procured another horse, Bismarck was a mere speck on the distant horizon, and he was steadily making deeper into the sandy waste. I followed him for hours, for I hoped to save him from the certain death from thirst that awaited him, but in the end the animal that I was riding gave in, and I was obliged to retrace my steps on foot, leading him behind me, and when I last saw my poor misguided horse, he was still going to his doom.14

In actual fact, the plain around Garub was and still is abundantly grassy, providing enough fodder for generations of warhorses to survive to this day, despite successive droughts. That Boer commandos bred their horses for endurance could be further proof of the Garub horses’ ancestry.

The animals are fine specimens – lithe with classically equine heads in chestnut, black, bay and grey – definitely not the progeny of heavy draft animals from Kolmanskop, nor transport mules or ponies. Here and there one can detect the flared tail of an Arab, the broad face of a boerperd and the graceful movement of a thoroughbred. It is a wonder that no one has tried to round them up. This may be because Garub falls under the protection of the large NamibRand and Sperrgebiet exclusion zones, meaning that no one is allowed to move off the bisecting highway to Lüderitz without a special permit. The area was deemed off-limits thanks to the expansive alluvial diamond deposits in the southern Namib, which prompted the authorities to restrict entry as early as 1908. This inadvertently allowed the feral horse population to remain isolated and flourish without the interference of ranchers and hunters. Nowadays there are man-made waterholes to see the horses through times of drought, courtesy of concerned humans. The Garub horses are most certainly a living legacy of Botha’s campaign.

Another legacy are the rusty and bent single-gauge tracks of the original re-laid railway line that now lie half-buried in the sand. The tracks begin a few metres from the modern highway embankment and run at a slight angle, about thirty degrees, away from the current railway line in the direction of the horses’ man-made waterholes. It is possible that these are the restored original wells. The old Garub railway station still stands, the German architecture evident but otherwise dilapidated. The stump of an old tree stands guard.

Outside Aus, a few kilometres off the main road, is a wartime graveyard. Many of the graves are German, which is at first surprising, since there were no German casualties at Aus thanks to their prudent retreat before the South Africans even began their advance. The sign reads ‘Commonwealth War Graves’, but the Commonwealth of Nations, a term coined by Jan Smuts, was not yet in existence in 1915; and besides, Germany was never part of the Commonwealth. There are a few South African graves dated 1915. These men were probably killed by mines or booby-traps as they entered Aus.

The German graves date from some years after Aus was abandoned. These men either would have been killed elsewhere in the campaign and were residents of Aus or, more likely, would have died in the South African prisoner-of-war camp that was established there after the campaign and midway through 1915. Upon defeat, the main body of the rank-and-file Schütztruppe was interned. The interns probably died from festering wounds sustained in battle or from diseases. Many of the headstones – both German and South African – are engraved with the years 1918 and 1919. It was during this period that the Spanish flu killed almost 500 million people worldwide. When the flu raged through the camp it spared neither guard nor prisoner: about sixty soldiers of each side died in Aus between October 1918 and April 1919, just before the prisoners were finally released.

The rest of the graves, both German and South African, indicate deaths at different periods after the war, thus explaining the use of the term ‘Commonwealth’. As a mandate of South Africa, South-West Africa became by default a member of the Commonwealth until South Africa declared itself a republic in 1961. In 1917, the Imperial War Graves Commission was set up in Britain to honour service personnel who died during the First World War. It was later expanded to include all those who died in later conflicts involving Commonwealth nations, regardless of rank, race, religion or allegiance, hence the inclusion of Germans in the cemetery at Aus. Renamed the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, it still functions to this day. Each South African gravestone near Aus is engraved with a springbok head, while the German graves typically carry the Maltese cross.