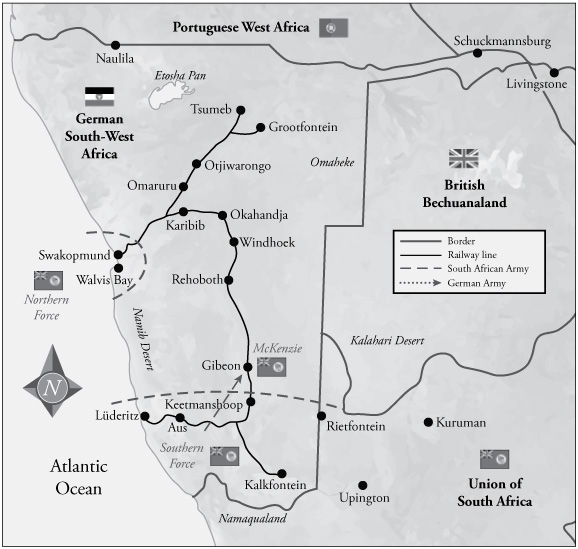

Botha’s multi-prong attack on the enemy positions in the week following 28 April 1915

11

Closing in

MAJOR VIKTOR FRANKE did not have time to rethink his strategy after the Trekkoppies affair, because Botha was ready to resume his offensive. The general had decided to double his force for the new push and had begun steadily concentrating a much greater mobile force at Riet since 25 April, which may explain why the Germans retreated without engaging, when they saw what they faced. The two mounted brigades that took part in the operations a month earlier were now combined into one large brigade under the overall leadership of Brits. Alberts remained in charge of the 2nd Mounted Brigade, while Colonel Lemmer took over from Brits to lead the 1st. Botha added the combined 3rd and 5th Mounted Brigade and placed them under the capable leadership of a newcomer to the campaign, Brigadier General M.W. Myburgh, who, like most of Botha’s commanders, had served with him during the Boer War. Before that, Myburgh had been with Botha in the short-lived Republic of Vryheid in northern Natal, a tract of land that the Boer mercenaries had been awarded for assisting King Dinuzulu in his fight to ascend the Zulu throne. Collyer describes Myburgh as tall and powerfully built, ‘broad-minded and tactful, determined and a good disciplinarian’, someone who ‘enjoyed the well-deserved confidence of his chief’.1 Like Alberts, Myburgh represented a constituency in the Transvaal.

The 3rd Mounted Brigade, led by Colonel Mentz, was made up of predominantly Afrikaans-speaking commandos – in fact, all the men on the left wing came from Botha’s and Myburgh’s country districts within the former Vryheid Republic. The 5th Mounted Brigade, commanded by the prime minister’s nephew, Hermanus ‘Manie’ Botha, was made up of Free State commandos, but since many Afrikaans Free Staters had participated in the previous year’s rebellion, at least half the commandos in this brigade were English-speaking. This was unusual given that the commando system was predominantly a Boer phenomenon.2

There was no better man to lead them than Manie Botha. Cut from the same cloth as his uncle, he had been a valuable young lieutenant in De Wet’s commandos during the Boer War and had led many daring raids in the latter stages of the conflict before his capture near Frankfort in the Free State in 1902. In 1915 he was still a young man in his thirties and, when faced with a do-or-die endeavour, his youthful exuberance allowed him to instinctively let go of the reins.

In all, Botha had almost 9 000 rifles and sixteen artillery guns under his command.3 In terms of men, his was a vastly superior force, but Franke still possessed superior weaponry and held a powerful defensive line. Botha’s attack had to follow the increasingly irregular terrain of the Swakop River, through an area still denuded of good grazing and water. The buttresses of the Tsaobis and Khomas Hochland mountains loomed further up ahead on the south bank, and the north bank was no less rugged. Provided Botha executed the predicted frontal attack, the Germans would have no trouble checking the South African advance with correctly positioned defensive lines.

The Khomas Hochland prevented any movement directly towards Windhoek, and so all Franke had to do was defend the Swakop and its north bank. The old capital of Otjimbingwe and the hamlets of Groot and Klein Barmen further upriver were already well defended to prevent the South Africans making directly for Okahandja, a town astride the railway line north of Windhoek. Franke knew that such a move, if successful, would cut him off from his capital. Kubas Station, on the old Khan–Jakkalswater railway, was heavily defended, as was Usakos on the main line. Franke himself, along with his main force and Governor Seitz, was based in Karibib, the principal German town along the main railway line between Swakopmund and Windhoek.

What followed was classic Botha. With unexpected sweeping, speedy long-distance manoeuvres, he once again completely flummoxed the German command. On the evening of 28 April, Botha’s four mounted brigades departed from Riet. Myburgh broke off to the south of the river and skirted the far side of the Tsaobis Mountain, making for Otjimbingwe from the south-west. Twenty-four hours later, Brits moved directly up the river. While Alberts and the 2nd Mounted Brigade carried on to Potmine, the 1st Mounted Brigade, moving north of the river, split into two: one infantry wing under Colonel Wylie marched up the Khan–Jakkalswater track towards Kubas, while Brits took a commando wing towards Dorstrivier for a frontal attack on Karibib.4 In the meantime, Botha brought Skinner in as a diversion, instructing him to keep the Germans guessing by making every effort to advance up the heavily defended main line.

Botha and his bodyguard followed closely on Myburgh’s heels as far as Kaltenhausen, then swung north down to Potmine to join Alberts on the river. Along the way, they were briefly cut off from the main body and ran into a detachment of retreating Germans. One of Botha’s bodyguards later quipped that ‘if the Germans had not been in such a tremendous hurry to save their skins, they might quite easily have bagged the Commander-in-Chief with the whole of the personal and general Staffs’.5 Botha established his temporary headquarters at Potmine to better control the widely separated commandos to his right and left.6

Moore-Ritchie reckons that these manoeuvres ‘broke all known marching records’. He describes the initial march from Riet to Kaltenhausen, one that would be repeated over and again in the coming week:

Left [Riet] at 8 p.m., trekked by moonlight along the Swakop River for three hours, outspanned till an hour before dawn, and made Salem at 6.45 a.m. on April 29. At 9.30 that morning the column moved on again, reached outspan at twenty miles by 1.35 in the afternoon, rested for an hour and a half and pushed on again till a quarter before midnight, when we rode into Wilhelmsfeste. But the water was at Kaltenhausen, some miles further ahead of this military post. We reached it at 1.15 on the morning of the 30th. Animals took two hours to water in the bitterly cold morning air. The guards had not taken two steps on their beat before the sand was littered with sleepers that looked like dead men. These sleeping columns, some ninety to a hundred miles from the coast, were now half way to Windhuk [sic].7

The route along the river was mined in places and Botha’s column sustained some casualties – three killed and others severely wounded – but on the whole the South Africans were alert to the common spots for mines and accordingly avoided them.

Some of the other commandos did more than 320 kilometres in five days, causing Moore-Ritchie to exclaim: ‘It was some trekking!’8 Myburgh’s mounted brigades, especially Mentz’s 3rd, were pushed to the extreme of their endurance. After consulting with them at Kaltenhausen, Botha immediately dispatched Myburgh on to Otjimbingwe, some forty kilometres further on. The men and horses had barely rested before they set off. Luckily for the exhausted brigade, Otjimbingwe was quickly evacuated as the South Africans approached, yet Mentz’s men went beyond the call of duty and gave chase, capturing an officer and twenty-three men. The rest just managed to escape, thanks in part to the condition of the South African mounts, as well as a lack of local knowledge of the terrain, which created a gap for the galloping Germans to break through.

Otjimbingwe provided grazing and plenty of water, but the respite was to be short. A day later, Botha ordered Myburgh on another epic ride north to Wilhelmstal, a small station hamlet on the main railway line between Karibib and Okahandja. Here Myburgh blew up the line and destroyed the telegraph lines from Windhoek,9 realising Franke’s worst nightmare and effectively cutting off the Schütztruppe from their capital. The road to Windhoek was now open.

Botha’s multi-prong attack on the enemy positions in the week following 28 April 1915

The brigade’s feat was all the more impressive given that the commandos were on tight food and water rations. They were remarkably resilient and self-sufficient: they could survive on a meagre diet of rusks and biltong for weeks without needing vegetables or vitamins. Such capabilities were first seen during the Boer War, when the British thought their scorched-earth policy would render the guerrilla commandos inoperable. Rusks and biltong could last weeks and even months. The latter could be generated on the hoof by shooting any variety of wild game, cutting the meat into strips and salting it. The hard sticks were then stuffed into pockets, coats or saddlebags and were continuously chewed like tobacco.

While Botha was at Potmine, Smuts came up from the south via Swakopmund to discuss tactics with his commander-in-chief. It was here that the decision was taken to disband the Southern Army.

Smuts was appalled to learn of the prime minister’s continued disregard for his own personal safety. Botha was often at the front lines of the fighting so he could get a clearer picture and take charge of procedures. This had certainly been the case at Riet, when he had moved up to the front to reorganise Brits’s defence and protect his artillery. On hearing about Botha’s brush with the Germans on the road to Potmine, Smuts demanded that Major Trew, the commanding officer of the prime minister’s bodyguard, never allow Botha to unnecessarily endanger himself again, to which Trew replied, ‘That’s all very well sir, but will you tell me what to do when the Commander-in-Chief tells me to go to hell?’10

At Potmine, Botha and Smuts received intelligence that Colonel Wylie had arrived at Kubas unopposed. This prompted Botha to redirect Alberts further upriver to the defensive positions at Groot and Klein Barmen, where they discovered the Germans hastily retiring north to Karibib. The enemy no doubt appreciated the value of Botha’s outflanking move and made the precautionary dash for Karibib lest they be cut off from Franke. Botha was now in a position to concentrate all his forces, currently spread across a 320-kilometre arc, on Karibib.

Skinner moved up the line from the west, Wylie and Brits from the south-west, Botha from the south and Myburgh down the tracks from the east.11 Franke’s only option was to retire north along the Otavi line towards Omaruru, allowing Botha’s forces to enter Karibib unopposed on 5 May. The town was the cherry of the campaign. As Collyer neatly puts it:

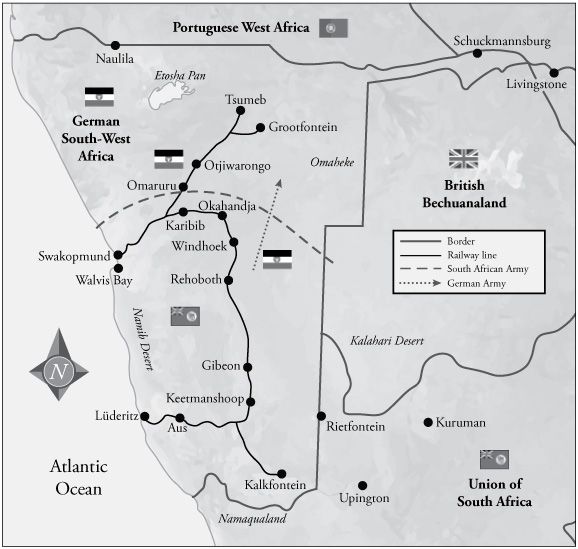

Botha held a small portion of German territory on 28 April 1915

On April the 28th the German commander held by far the greater part of the protectorate and held and covered the capital, Windhoek, and the railway, which gave him power to concentrate and take the initiative. His opponent controlled merely that small portion of the country that lay behind their outposts. A week later General Botha’s movements had deprived the enemy of the capital, of his power of concentration for attack, of the initiative and of two-thirds of the settled portion of the Protectorate.12

A week later and a much altered picture. On 5 May, Botha is in control of two-thirds of the territory

On 6 May Botha himself rode triumphantly into Karibib. Here the South Africans came into contact with the German civilian population for the first time during the campaign. Botha was met by a nervous delegation headed by the mayor, who formally handed over the town and asked if the people could remain in their homes and not be deported. Of more importance, he asked if they could keep their own food supplies. There was a desperate shortage of food among the large bodies of troops moving into Karibib from all directions. Many of the soldiers were on their last rations and were doubtless expecting the population to provide. Botha, however, agreed to the request and issued a directive forbidding any member of his hungry army from looting food from the civilians.

Much has been made of the ‘stoical grit’ of the starving soldiers at Karibib.13 Lieutenant Commander Whittall describes the weeks following the initial occupation: ‘To say that a virtual famine existed does not exceed the truth. Everyone was on the shortest of short rations. Even the hospitals were living from hand to mouth.’14

The food shortage was not unexpected. The lines of communication stretched some 250 kilometres from Swakopmund, up the Swakop River, to Karibib. The wagon mules were completely worn out and for the next three weeks only driblets of food made it through. The repairs to the Khan–Jakkalswater railway were still 100 kilometres short of Karibib. Communications were eventually switched back to the main line through Usakos, but that took a further two weeks to repair. Considering the dire supply circumstances, Collyer makes special mention of Lieutenant Colonel Collins, whose indefatigable energy in charge of the South African railway engineers helped to finish the line by mid-May, relieving Botha of a persisting logistical headache.15

Still, it was five weeks before rations and supplies began to arrive in sufficient quantities. The conduct of the South African troops during this time could not be faulted. Moore-Ritchie writes:

The very confidence of these German townspeople that they had nothing to fear from the hated troops of the Union of South Africa was eloquent … The news of the Lusitania massacre on the high seas reached Karibib just after occupation. Did one Teuton in the place have to suffer as a consequence even the insult of a word? No … General Botha’s forces had crossed a desert through which it was the open boast of the enemy that it was strewn with mines and with every well poisoned. Was a single defenseless citizen of Karibib the worse for it after the occupation? Not one. The greater part of General Botha’s forces were on a half – a quarter – an eighth rations when they made Karibib … they lived until all supplies could come up on less than one biscuit a day, a pinch or two of meal, and fresh meat. How much looting occurred in these towns? There was none worthy the name.16

Even the Germans acknowledged the behaviour of their captors. A local newspaper reported that the South Africans behaved ‘properly and courteously’ and ‘in such a way as becomes civilised soldiers’.17 Indeed, the civilian population benefited from the occupation by selling their own food rations at ridiculously high prices, and the soldiers paid without so much as a mutter, such was their respect for their commander-in-chief’s orders.18

Karibib was a strategic centre as it commanded the main railway line from Swakopmund all the way to Windhoek, as well as the junction of the narrow-gauge track north to Tsumeb, up which the Schütztruppe and Seitz’s governmental entourage had hastily retreated as far as Omaruru.

Most German citizens realised they were fast losing their grip on the colony, but they hoped that the war in Europe would go in their favour. To deny the South Africans, Windhoek was abandoned by all military personnel, who joined Franke at Omaruru. The move paralleled that made by the Boers against the British over a decade earlier, when they abandoned the capitals of their two republics to fight a protracted guerrilla war.

Nevertheless, Windhoek remained a glittering prize. Botha sent Alberts from Barmen to join Mentz at Okahandja in order to secure his own route to the capital. Thanks to Smuts’s intelligence gathered after the battle at Gibeon, Botha knew von Kleist was moving somewhere to the east of Mentz, trying to link up with Franke. The prime minister set out to make that task more difficult and ordered some of Mentz’s commandos to go after von Kleist and push him wide of Omaruru, forcing him towards the Waterberg mountains. The commandos managed to capture 157 soldiers, although they were not part of von Kleist’s unit, belonging instead to a group retreating north after leaving Windhoek a couple of days earlier.

Without any German soldiers to defend it, Windhoek was ready for the taking. Botha ordered Alberts and the remainder of Mentz’s brigade to surround the capital and then took a motorcade to the outskirts of town. At 11 a.m. on 12 May, Botha met the mayor, who was ‘betraying symptoms of considerable nervousness’.19 Under the shade of an acacia tree, Windhoek was ceremoniously handed over. An hour later, it was swarming with South African troops.

The wireless station was intact, but the Germans had removed or destroyed the working parts before the South Africans arrived. That they had left the mast revealed the Germans were convinced the occupation was just temporary.20 They were sure their troops in Europe would defeat the Allies and the colony would be regained. Reitz, who was fluent in German, noted this sentiment when he and his motoring comrades entered Windhoek from the south a day after the occupation. The German newspapers ran daily articles hinting at the temporary nature of the situation. One reads:

The early occupation of Windhoek by the South African forces is unavoidable … The occupation can at most continue for a week or two as dire calamity has overtaken the Allies in Europe … we may say with confidence that the enemy’s banner will not long float over us.21

The civilians were polite yet aloof, says Reitz. They were seemingly confident that the South Africans would soon pay dearly for having challenged the might of imperial Germany. But Reitz knew from his own bitter experience in the Boer War that they were just trying to keep their chins up.22

By occupying Windhoek, Botha had achieved all the strategic objectives laid out by the subcommittee of the Committee of Imperial Defence. By all accounts, he had done his job and could now pack his bags and go home. But Botha had his own ideas. ‘Botha’s aims were patently South African rather than imperial,’ notes Hew Strachan.23 The prime minister could now focus on his own plans. But he worried that the Schütztruppe would resort to guerrilla warfare, just as he and the other Boer generals had done so successfully against the British. The land to the north, where the Germans had retreated, was conducive to a protracted guerrilla campaign, as the region was vast, included large, unexplored tracts of Portuguese territory, and provided better grazing and game than the south of the colony. Botha knew that hunting down small bands of Schütztruppe in this thickly bushed environment would be near impossible.

Yet for him it was essential that the Germans be completely defeated, and quickly. He did not want them to retain sufficient territory to uphold Germany’s claim to the colony if peace negotiations were to take place in Europe. He was also mindful of the effect of a drawn-out campaign on the South African public back home. When Reitz arrived in Windhoek, Botha expressed to him his concern that Hertzog and the nationalists were ‘conducting unceasing propaganda against the expedition’.24 He was keen to wrap things up as soon as possible.

Thus, with Mentz’s 3rd Mounted Brigade duly installed to mind the capital and its civilians, and Berrangé’s 5th Regiment of Mounted Riflemen policing the southern sector of the colony, Botha hurried back to Karibib to plan his final move.