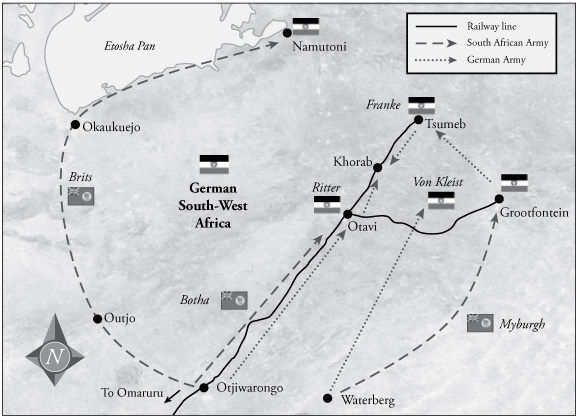

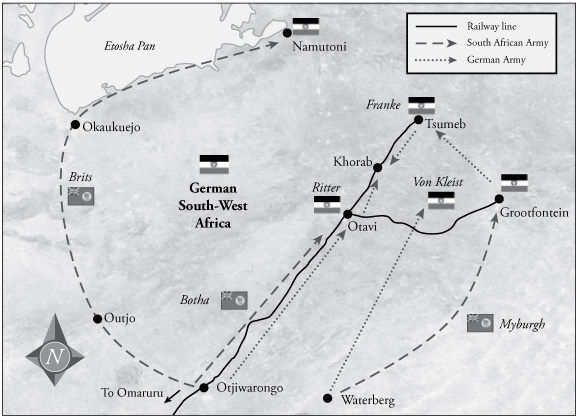

Pushing man and beast to the limit. Botha initiates great sweeping manoeuvres in an effort to surround the entire German force at Otavi and Tsumeb

12

In for the kill

GERMAN GOVERNOR THEODOR SEITZ was in no mood to adopt guerrilla tactics. Neither was his military commander. Unlike von Lettow-Vorbeck in East Africa, Franke, based on recent experience, believed that the South African commandos would easily overrun small isolated bands of German troops. Furthermore, he could not rely on African villages for supplies as his counterpart did in East Africa, because most tribes in the South West were unsympathetic to the German cause, especially after what had befallen the Herero and Nama. German-owned farms would not be able to supply all the troops, and even if they did, they would attract the wrath of the South African soldiers. As both Franke and Seitz were at pains to maintain the safety of civilians, they would not even consider this last option.1

The Germans’ air support had by now also ceased operations. Fiedler’s Aviatik had suffered permanent mechanical failure and Trück’s aeroplane was also damaged beyond repair. Von Scheele flew his last mission sometime in May, crashing into a thorn tree near Karibib. He survived, but his Roland did not. It was von Scheele’s eighth crash in the war and the fourth in which he sustained injuries.

Nevertheless, had Franke the inclination for guerrilla warfare, it may have lengthened the campaign considerably, a possibility that Botha could ill afford. It was arguably Franke’s best course of action and it certainly would have been Botha’s had he been in the German commander’s position. The Ovambo, for instance, had never liked the Herero and were relatively sympathetic to the colonialists, particularly after Franke routed the Portuguese in Ovamboland. A protracted guerrilla campaign using Ovambo bases in the north of the colony and in present-day southern Angola may have proved worthwhile. Franke did consider it, but a famine was raging across Ovamboland at the time and he may have felt it would be too much to test the fragile goodwill of starving villagers.2 He did not discount guerrilla warfare entirely, but he believed he still had one or two other options available to him.

With Botha busy mobilising the largest force of the campaign at Karibib, Seitz and Franke decided to sue for peace on terms that would favour continued German governance. The two men, like many of their compatriots, were convinced that Germany would succeed in Europe. Their objective in opening talks with Botha was twofold: firstly, they wanted to retain enough territory in the colony to uphold Germany’s claim to it when European peace negotiations commenced and, secondly, they hoped to sidestep their inexorable defeat.

Botha received Seitz’s written request for a ceasefire from a dispatch rider who intercepted his motorcade as he was travelling back from Windhoek. At midday on 20 May, at the base of a hill called Giftkop, roughly midway between Karibib and Omaruru, Botha, Seitz and their respective staff met under the umbrella-like shade of an acacia tree. Collyer, who sat next to his commander-in-chief, says the meeting was ‘conducted virtually entirely by the Governor who was vehement, and even aggressive, in his bearing’.3 He describes Seitz as a small man who ‘made up for his lack of inches by occasionally impressive utterances, and once or twice threatened his auditors with the displeasure of sixty millions of Germans’.4 According to Meintjes, Seitz actually said something like:

Mr Botha you are not an Englishman. Your people were robbed of their country by the English. We wish to be your friends. Are you now prepared, on behalf of your people, to incur the hatred of seventy million Germans?5

Botha responded that he was. Echoing Reitz’s earlier sentiments concerning the attitude of the German civilians in Windhoek, Collyer notes that the governor’s bolshie demeanour clearly indicated he was bluffing and that in reality his morale was low.6

In contrast to Seitz’s ‘aimless discussion’, Franke, in full uniform with sword, medals and tassels, hardly spoke.7 Perhaps it was in deference to his governor or, more likely, to Botha, whom he had not met before but must have admired as a soldier.

The gist of Seitz’s diatribe was to cease hostilities between the two armies and maintain a status quo. The South Africans could remain in occupation of their recently conquered territory, while the Schütztruppe would be in charge of their section to the north until the end of the war when a European peace treaty would decide the fate of the colony. Botha listened patiently for a long time, ‘due mainly to his own reluctance to wound the feelings of Dr. Seitz’, once again displaying his characteristic conciliatory nature through calm and attentive conduct.8 When Seitz eventually ran out of steam, Botha simply and politely replied that unconditional surrender was all he would accept. The meeting terminated amicably and the men went back to their respective lines, Botha to prepare for his advance and Seitz for his retreat.

The South African lines of communication were finally running smoothly and Skinner, now a brigadier general, had been given charge of them. With his customary nervous energy, and with the help of the 3rd and 5th infantry brigades and the Cape Town Highlanders, he had completely overhauled and reorganised the supply lines. There were now enough horses, wagons and ammunition to enable each of Botha’s five advancing brigades.

It was during this period in Karibib that the South African Aviation Corps (SAAC), the forerunner of the South African Air Force, was deployed for its first ever operation. Back in 1912, General C.F. Beyers had told Smuts of the value of aircraft for military purposes. On Beyers’ advice, Smuts had immediately ordered the establishment of a military flying school in Kimberley. The first South African military pilot, Lieutenant Kenneth van der Spuy, graduated on 2 June 1914 and the SAAC officially came into being on 29 January 1915.9

Botha had been impressed with the reconnaissance and strafing results of the German airmen during the opening phase of the war and, as a result, had ordered some aeroplanes for himself. He was itching to counter the German monopoly of the vast Namibian sky. An airstrip was consequently built at Walvis Bay and the first South African military operational airfield was constructed at Karibib in early June 1915. The first aeroplanes to arrive at Walvis Bay were six French-manufactured Henri Farman HF-27s.10 The Farmans were chosen over British and American models as their steel-tube fuselages were deemed more suitable to the hot, dusty desert conditions than the wooden construction typical of Anglo-American aircraft.

The aeroplanes were practically obsolete in the European theatre of operations by the time they arrived in Karibib in June, the model having undergone a series of modifications to correct its reputation for being underpowered. Botha, however, was no longer concerned with power or manoeuvrability, since the three German aircraft were out of commission by then. He would use the aircraft primarily for reconnaissance and the odd (ineffectual, as it turned out) bombing raid, in which the pilot would drop hand grenades.

On 18 June, with the airfield now on line, Botha rode out of Karibib. Brits was ahead of him with 1 500 rifles and four 13-pounder quick-firing artillery guns, making directly for the German lines at Omaruru. Lukin, now back in action, was to leave his base at Usakos with 2 200 rifles and another four 13-pounders, and move in a sweeping arc from the west via Erongo to slot in on Brits’s left flank. Newly promoted Brigadier General Beves was to follow Lukin’s 6th Mounted Brigade with the 1st Infantry Brigade of 2 550 rifles, a further four 13-pounders, a number of Howitzers of various calibres and the Royal Navy armoured car division. Brits’s right flank, far to the east, was to be manned by Myburgh with the 2nd Mounted under Alberts and the right wing of the 3rd Mounted under Lieutenant Colonel Jordaan. Equipped with some 13-pounders and two 12-pounder naval guns, they were to chase down von Kleist, who was moving in the direction of the Waterberg mountains. Between Myburgh and the main body was another newly promoted brigadier general, Botha’s nephew Manie and his 5th Mounted Brigade of Orange Free Staters.11

By the time Brits arrived in Omaruru on the morning of 20 June, the Schütztruppe were gone, having retreated along the railway line but not before blowing up the bridge spanning the river. Over the next twelve hours, Botha, Lukin and Beves joined Brits at Omaruru, while Manie Botha and Myburgh had minor engagements with the retreating Germans as they pushed north in their respective sectors. Each lost a man in the fighting.

It was while he was at Omaruru that Botha ordered the first South African–piloted military aeroplanes to take to the skies. He was thrilled with the reconnaissance results, exclaiming ‘now I can see for hundreds of miles’.12 It was a welcome change for the commander-in-chief, who had spent hours peering through binoculars from the tops of sun-exposed rocks.

The aeroplanes were a timeous addition, for the battle was about to move into thick, undulating bushveld, which made accurate ground surveillance of enemy movements almost impossible. After their very first mission, the pilots were able to accurately report that the Germans were not digging in at Kalkfeld as expected.

On the evening of the 20th, after Botha spent the day on the hill just outside Omaruru reconnoitring the land to the north with his trusty binoculars, the advance resumed.13

Today, in contrast to Karibib, Omaruru is quite pretty. It has a broad avenue lined on either side with large shady trees and old colonial buildings. Apart from the modern petrol stations and the tar on the main road, the place has changed little since 1915. If Louis Botha were to see it now, he would recognise most of its features, including the old railway bridge and Franke Tower, a tall stone tower with a castellated top. European in its design, it is dedicated to Erich Viktor Carl August Franke, commander of the Schütztruppe in German South-West Africa.

Franke was something of a hero in Omaruru, having come to the town’s rescue when it was besieged during the Herero uprising in February 1904. It seems he conducted a Botha-style march from Gibeon, covering 400 kilometres in just over two weeks, to relieve the town with numerically inferior numbers. In recognition of this feat, the town fathers erected the strange tower in his honour.

Kalkfeld is a settlement between fifty and sixty kilometres up the railway line from Omaruru. According to Moore-Ritchie, ‘It had been predicted with the utmost confidence that the Germans would here put up a fight.’14 Indeed, Collyer notes: ‘If the German Commander intended to make a stand anywhere, nature had furnished him with a position at Kalkfeld ideal for the purpose.’15 Botha could therefore hardly believe his airmen’s report that the Germans had abandoned yet another strong defensive position. It was nevertheless confirmed when his nephew occupied Kalkfeld on the morning of 24 June, having rapidly swept in from the east ahead of Lukin in an unsuccessful pincer effort to cut off the retreating Schütztruppe.

An exasperated Botha abandoned his bodyguard at Omaruru, got in a car and drove to meet Manie at Kalkfeld, arriving later that morning. He decided then that a far wider and faster sweeping manoeuvre was required if the South Africans were to catch the slippery Germans before they decided to entrench themselves behind their last available natural defences at Otavi or Tsumeb, or ran out of railway line and were forced into using guerrilla tactics.

Pushing his men and horses to their limits, Botha hurried a further fifty to sixty kilometres up the track, making for Otjiwarongo. Denied rest and time to consider their position, the Germans were forced to shift up the line to Otavi. At Otjiwarongo, the South Africans encountered surface water for the first time on the campaign, but Botha was not about to hang around to water and rest his troops.16 He ordered them on after less than a day.

After Omaruru, the geography flattens out and is overtaken with low dense shrub. Even though the vast area is densely wooded, it is not quite good enough for agriculture, as there is not enough water to sustain major crops. It is not suited to cattle ranching either. The cattle, although ‘Africanised’ as semi-browsers, still prefer to graze and this is exclusively browsing country. One can understand Botha’s wish to pass through the region quickly. Apart from the dams around Otjiwarongo, there is little food and water for horses.

Botha had lost contact with Myburgh, now far on his right flank, but was unconcerned. He knew that his dependable general was probably well on his way to the Waterberg. In fact, Myburgh was already there, having chased von Kleist’s haggard troops from that mountain range, incidentally the scene of the Hereros’ last stand against the Schütztruppe in 1905. When communication was eventually established with Myburgh, Botha ordered him to ride on quickly to Grootfontein, east of Otavi.

In the meantime, Brits was instructed to encircle the Germans from the west with the 1st Mounted Brigade. It was to be an epic ride: Botha expected them to cover some 400 kilometres of thick bush, moving in a large arc from Otjiwarongo via Outjo and Okaukuejo to the German fort of Namutoni. Located on the south-western rim of the giant Etosha saltpan, these days Okaukuejo is a sprawling rest camp complete with lawns and a swimming pool. From there, Brits was to ride due east to the eastern rim of the pan and attack the white-walled fort, which is today also preserved as a rest camp in the Etosha National Park.

The capture of Fort Namutoni had long been part of Botha’s plan.17 As early as April, he had learnt from wireless interceptions that the fort held a large number of prisoners of war who had been convalescing there since the reversal at Sandfontein; but, more importantly, the fort was a vital link in the German line of escape should they decide to flee to Ovamboland. With Namutoni in Botha’s hands, guerrilla warfare would be even less appealing to Franke. Furthermore, if Franke were to somehow check Botha’s advance up the railway line, he would also have to contend with Brits, who would threaten his rear, as would Myburgh if he was successful in taking Grootfontein.

It was essential that the outflanking move on Namutoni be conducted with the utmost secrecy, otherwise Franke would clearly detect the ruse. This explains Brits’s early breakaway from the main body at Otjiwarongo. The manoeuvre was so wide that the Germans would not be able to see the dust column from their positions along the railway line.

Brits’s ride was an extreme test of endurance for both man and horse, one that equalled if not bettered T.E. Lawrence’s overland journey with Arab rebels to take the Turkish-held port of Aqaba two years later. Interestingly, the only casualties of Brits’s epic ride were not the horses but the armoured cars of the Royal Navy attached to his brigade. The rough roads and heat proved too much for the Rolls-Royces and they were returned to Botha, who was able to make better use of them along the relatively graded wagon track that ran alongside the railway line.18

By 27 June, according to Botha’s aerial reconnaissance, the Schütztruppe had halted at Otavi, eighty kilometres from Otjiwarongo.19 It was here that Franke decided to make use of the natural features and dig in. The track was running out, yet Franke was determined to hug the umbilical cord of his railway line, which terminated at Tsumeb thirty kilometres ahead. If he was to buy any more time, it would have to be here.

Otavi was strategic for the defenders for two reasons: it had good natural defences, especially to the east of the railway, and it had plenty of water in the rear for the defenders, with none in front for the attackers. Collyer calculated that the Germans had to check the South Africans for just two days before the attackers would be forced to return to Otjiwarongo for water.20 Franke entrusted Major Ritter with securing the defences and gave him seven companies with ten machine guns and a staggering thirty-six artillery pieces, including one of the 13-pounders captured at Sandfontein.21 This was a considerable amount of firepower compared to what the South Africans had. The latter had been forced to sacrifice their heavy artillery for greater mobility.

Leaving Ritter in charge, Franke retreated to the rear at Tsumeb, where he made his headquarters. Here he could rely on another considerable munitions arsenal, as well as two regular and three reserve companies at Khorab Station in between himself and Ritter’s forward position. Franke believed he could hold back the South African horsemen, at least long enough for Botha to reconsider the peace terms. He also believed he had left enough space between himself and Botha to prepare his defences. But, like von Kleist at Gibeon, Franke underestimated the speed of the South African advance.

For the umpteenth time, the Germans wrongly assumed that the South Africans would make exclusive use of the railway line, which they would have to repair as they advanced. But Botha once again proved that horsepower and speed were king in this environment. Galloping along the road parallel to the damaged tracks, early on the morning of 1 July – less than forty-eight hours after the German forces arrived in Otavi – the first South African troops appeared on the horizon, with Botha among them. The Germans were flabbergasted.

Ritter had not had adequate time to prepare his defences.22 Before they could even set up machine-gun and artillery positions, let alone build schanzes or dig trenches, the South Africans swooped in on the German positions. Manie Botha’s 5th Mounted Brigade led the charge directly up the railway line, while Lukin’s 6th Mounted branched off to the right to attack the positions on Elefantenberg, an oblong mountain jutting perpendicularly east of the railway. Botha, following his nephew’s Free Staters up the line in a car, brought up the immediate rear. His motorcade had to exercise some caution because the Germans had managed to lay a few mines on the roads. Lukin had to contend with the bulk of them on the eastern road, but he prudently kept his horses off the worn defiles as they steadily encircled Elefantenberg.

Botha was just minutes from his front lines, which had already begun to engage the first German outposts.23 After pausing briefly to learn the name of a mortally wounded young Free Stater on the roadside, he continued hot on the heels of the 5th Mounted, who had by then brought up their light artillery to fire on the half-entrenched Germans on the western spur of Elefantenberg. The dense bush hampered proper communication between the forces converging on Otavi and so Botha decided to position himself between his two brigades to manage the operation more effectively, even though it put him dangerously close to the action. Ingeniously, he used motor-cyclists to dispatch messages to both generals.24 It was another first for South Africa. Until then, these messengers were nicknamed ‘gallopers’ for the horses they used.

Botha was concerned about the excellent natural defences and thick cover that the area offered the defenders, and was convinced he was pitted against the full might of the Schütztruppe. Despite not having all his guns in place, Ritter could still conduct a partial artillery assault and disrupt the South African attack, which was already disconnected by thick bush and dust. But the Germans were erring on the side of caution. Instead, Ritter deployed in depth by staggering and splitting his lines between Lukin and Manie Botha. His objective was to enact a fighting retreat away from Otavi and off the Elefantenberg back towards Otavifontein and the protection of the Otavi Mountains.

Pushing man and beast to the limit. Botha initiates great sweeping manoeuvres in an effort to surround the entire German force at Otavi and Tsumeb

Ritter was, in fact, retiring to a far stronger defensive position. The Otavi Mountains in the north and the Elefantenberg in the south formed a neat horseshoe on three sides of a valley that opened to the west where a secondary railway line branched off for Grootfontein. Naturally, the spirited commandos of Manie’s 5th Mounted Brigade gave chase and charged straight into this enclosed valley before Ritter was able to properly prepare his artillery positions. If he had had even an hour, the South Africans would have been blown to pieces.25 But Manie, astutely aware of their predicament, had made a choice – to charge in rather than retreat. Says Collyer admiringly:

The 5th Mounted Brigade had become committed to their tactical enterprise in the manner in which commando units often entered a fight induced by the instinct of the individual to take a sudden line of action.26

The speed of the attack sent the Schütztruppe into a panic and they bolted, leaving three dead, eight wounded, twenty bewildered prisoners and the last of their natural defences defenceless. Botha and his chief of staff were baffled as to why the Germans fell back this last time. Although the number of South African soldiers facing them was approximately equal to theirs – about 3 500 rifles – the Germans held the high ground and had considerably more heavy guns. Why not choose to stand and fight?

The South Africans were not complaining. When Manie Botha pushed Ritter off the Otavi Mountains, he secured the best water of the whole campaign for the Union forces.27 The train station at Otavifontein was the source of a clear, strong-flowing rivulet. It would have been a useful base for the South Africans had the campaign been prolonged.

Ritter’s retreat from Otavi should have pushed the Germans into the wilderness, but when Brits suddenly appeared and took Fort Namutoni from its astonished defenders without firing a shot, Franke could no longer see a way to guerrilla warfare. And when Myburgh, nipping at the heels of von Kleist’s ragged column, appeared at Grootfontein, equally out of the blue, the German commander gave up on the idea entirely. Grootfontein was actually captured by a lone signaller, Captain Poole. Customarily ahead of the main column, he was offered and accepted the surrender of the small town.

Franke failed to recognise that he still had one roll of the dice left. Thanks to continued air reconnaissance, Botha was aware that the combined German force directly facing him was far stronger numerically and in terms of firepower than his own two brigades. Brits and Myburgh were too far away to lend any immediate assistance should the Germans have chosen to counterattack.28 In addition, at that stage Botha had not yet received word from Brits at Namutoni and had no idea where he was, while Beves’s four infantry battalions and the heavy artillery were still five days behind. The 1st Infantry Brigade’s gamely march at an astounding average speed of twenty-two kilometres a day for sixteen consecutive days is a world record by some accounts.29 Nevertheless, Botha still had to wait for them to catch up before they could be brought into action. Furthermore, after days continually on the move, the horses of the 5th and 6th Mounted were in no condition to press home their advantage, and both brigades were forced to remain at Otavi and Otavifontein to recuperate.

All of this gave the Germans more than enough time to regroup for a counterattack, and indeed, on 2 July, air reconnaissance revealed that Franke had gathered almost all of his forces at Khorab Station. It certainly appeared as if an attack was imminent. But it never came. Collyer believes that had Franke counterattacked at that moment, he almost certainly would have pushed Botha’s two exhausted brigades back. He would then have been able to deal with Brits and Myburgh one at a time.30 Oddly, there was an intention to counterattack. The South Africans at Otavi picked up a written order left behind by the retreating soldiers. Issued by Franke, it read: ‘The time to retire and avoid the enemy is now past. We have arrived at the stage where we must and will fight.’31

For some reason, instead of fighting, on 3 July Franke persuaded a reluctant Seitz to send a message to Botha requesting a cessation of hostilities. At their second meeting, Seitz again hailed the strong position of the German armies in Europe and proposed to maintain the status quo. Botha flatly refused, aware that his position was becoming less tenuous by the hour with Franke’s reluctance to act decisively.

Brits’s capture of Fort Namutoni ultimately prompted Franke to begin persuading Seitz to surrender. The Schütztruppe were surrounded and, he believed, irretrievably hemmed in. It would be a fruitless exercise to continue to fight and unnecessarily waste men’s lives. It was an unusual argument in a war made infamously iniquitous by decisions that cost hundreds of thousands of lives.

Botha, in the meantime, sent a motor car with a message for Myburgh. He was to move on Tsumeb and attack it from the north. Unbeknown to Botha but known to the German command, after releasing the detachment of prisoners at Namutoni, Brits had begun probing south towards Tsumeb as well.