Echoes from the Past

— By Jack Roth —

As we approached the Triangular Field on that cold, damp, misty morning, the only sounds that could be heard were the splatters of gentle raindrops deflecting off the moss-covered rocks and knee-high grass that saturated the landscape. It was six a.m., and the Gettysburg battlefield possessed a mystical quality, even more so than usual.

With heightened caution, we gingerly walked toward a wooden gate that acts as a landmark to where some of the bloodiest fighting took place in July 1863. We didn’t want to trip and fall on the soggy ground, so we stepped slowly down a rugged path. We reached a large rock under which we had placed an infrared camera and microphone the night before. They were wet despite the protection of the tarps we left covering them.

“A casualty of field work,” I thought, knowing that our technician would be less than pleased about the soaking of his equipment.

I carefully collected everything and handed it off to a fellow field investigator, who promptly took the equipment to the comfort of our heated car. We hoped the rain hadn’t destroyed whatever anomalies we may have captured on tape.

Confederate General James Longstreet, who led the Confederate assault on the second day of battle. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

I lagged behind, savoring the dreamlike atmosphere. I walked back up toward the wooden gate, thinking how great it felt to be on the battlefield without the usual hordes of tourists and busloads of noisy school kids. It was perfectly quiet, almost surreal. As peaceful as this felt, it was hard to believe that hell had once unleashed itself here.

And then I heard them …

The voices emanated from the bottom part of the Triangular Field by its northwest tree line. I initially deduced that I must have been hearing animals. I stopped in my tracks about thirty yards from the car in order to listen more carefully.

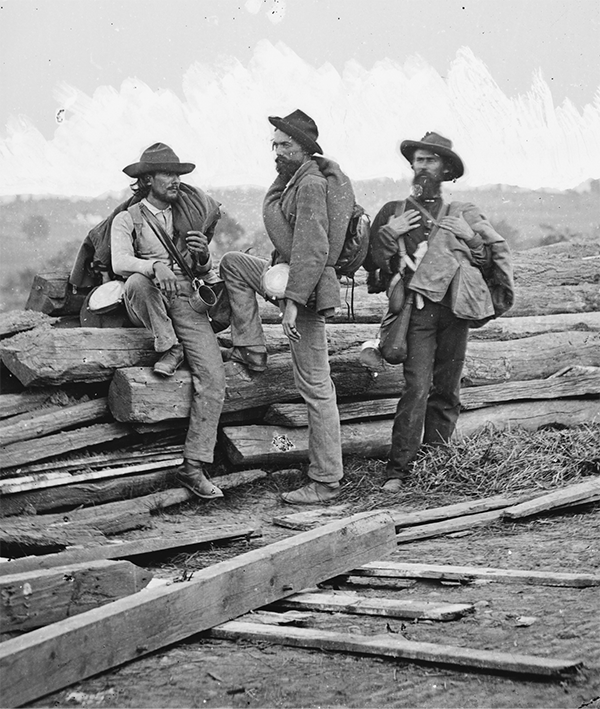

Did the wailing battle cries of Confederate infantrymen imprint themselves onto the battleground? Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

“Yip!”

“Hey!”

Silence for a few seconds and then more …

Muddled voices? Men screaming …

… coming up from the tree line toward where the Union line would have been holding ground …

“Yep!”

“Whoop!” “Whoop!”

Cows?

No way—maybe an angry farmer, but not cows.

School kids role-playing on the battlefield?

Not this early, and not in this weather.

I became unnerved.

I waited a few seconds to see if I could distinguish these sounds and pinpoint exactly where they were coming from.

They were getting closer, yet I couldn’t see anything. Once more I heard distant screams …

“Yep!” “Yip!”

And then silence.

I waited a few minutes to make sure the sounds had subsided. At this point, my fellow investigator opened the car window and stuck his head out.

“What’s up?” he asked. “Did you hear something?”

“Yes. I think I did,” I responded. “You’re not going to believe this, but I think I just heard rebel yells.”

The phantom sounds I heard that morning seemed to originate from the very landscape on which I was standing. Since my strange auditory encounter, I’ve become fascinated with the Triangular Field, an area of the Gettysburg battlefield that seems to retain a great deal of residual energy. Ringed in by stone walls and woods at the base and up the slope on the right, the field saw a lot of action because Confederate forces had to charge through it in order to take Houck’s Ridge and Devil’s Den.

There are several historical facts that support what I may have heard on that misty morning. The Triangular Field has become synonymous with the death and destruction associated with the whole of the Battle of Gettysburg. On the morning of the second day of fighting, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee believed that if he could simultaneously attack the Union flanks, he could drive the enemy from the field. Part of his plan was to send Gen. James Longstreet’s First Army Corps southward to overrun the Union left flank anchored on Little Round Top. In order to even reach Little Round Top, the Confederates had to endure some of the bloodiest fighting of the battle in terrain now referred to as the Triangular Field and Devil’s Den. Within just a few hours, thousands would be left either dead or wounded on these blood-soaked grounds.

As confederate brigades under the command of Gen. John Bell Hood made their way southward, they came upon a sloping, triangular field. Waves of Confederate troops from Texas, Arkansas, Alabama, and Georgia crossed this field, clashing with Union regiments from New York, Maine, and Pennsylvania. The Confederate forces were initially cut down by Union artillery posted on top of a small ridge adjacent to the large boulders of Devil’s Den, but the Confederates continued to push forward with repeated charges by the Fifteenth Georgia and the First Texas Infantry. Shouting the famous rebel yell, the First Texas charged up the Triangular Field to finally take the summit. The Georgians and Texans proceeded to overrun Devil’s Den and took three Union cannons as prizes.

Alexander Hunter, a member of Longstreet’s staff, later recalled in his memoirs how the rebel yell would adversely affect the enemy:

When our reserve, led by Hood’s Texas Brigade, the pride and glory of the Army of Northern Virginia, came on a run, gathering up all the fragments of other commands in their front, and this second line clashed straight at the enemy, then I heard the rebel yell with all its appalling significance. I never in my life heard such a fearsome, awful sound … I have often dreamed of it; above the uproar of a great battle it dominated. On those charging columns of blue it had a decided effect, for it portended capture, mutilation or death and brought eternity very near.

Indeed, the rebel yell was a battle cry used by Confederate soldiers during charges to intimidate the enemy and boost their own morale. Union soldiers, upon hearing the yell from afar, would guess that it was either the Confederates about to attack or rabbits in distress, suggesting a similarity between the sound of the rebel yell and a rabbit’s scream. The yell has also been likened to the scream of a wild cat, as well as similar to Native American war cries. One description says it was a cross between an “Indian whoop and wolf-howl.” Although nobody has ever actually heard the cries of the fabled banshees from Greek mythology, the rebel yell has often been compared to these blood-curdling wails simply based on their disconcerting effects on those who hear them.

Given the differences in descriptions of the yell, there may have been several distinctive yells associated with the different regiments and their respective geographical areas. Another plausible source of the rebel yell is that it derived from the screams traditionally made by Scottish Highlanders when making a Highland charge during battle. This was a distinctive war cry of the Gael—a high, savage whooping sound.

A great deal of documented eyewitness testimony supports the existence of paranormal activity in the Triangular Field. Confederate sharpshooters have been sighted on the rocks down at the bottom of the field, at the end of the woods, as if preparing to shoot. Strange sounds have been heard, including screams described as rebel yells, emanating from either the wooded area to the right of the wooden gate or down at the bottom end of the field. Artillery blasts have also been heard, as well as the screaming and moaning of wounded and dying soldiers. Union soldiers have been spotted at the left of the gate entrance of the field and have even been known to approach visitors.

Suffice to say, the Triangular Field remains a focal point in our research at Gettysburg. Although perhaps no more haunted than any other part of the battlefield, the smaller, more enclosed nature of the field makes it an ideal place in which to set up a triangulation (no pun intended) of recording equipment, thus making full coverage of the field plausible. In the end, the range and frequency of paranormal activity experienced in this small field cannot be ignored.