The Eternal Battle

— By Jack Roth —

Nestled on the crest of the southern slope of Little Round Top, the patch of ground where Union Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and the Twentieth Maine repulsed Confederate attempts to collapse the Union left flank appears inconspicuous enough. In fact, when we attempted to find this location during our first-ever visit to the battlefield, we struggled to find it. Once we did, paranormal activity began in earnest before we could even unpack any of our equipment.

We arrived at the battlefield on a beautiful fall afternoon, drove around and eventually headed toward the two rocky hills that marked the locations of Little Round Top and Big Round Top. Winding roads lined with memorials guided us around the Valley of Death and Devil’s Den, and finally to the base of Little Round Top.

As we drove, we felt overwhelmed by the significance of the location. We were in Gettysburg, where for three days in 1863 some of the most vicious and costly fighting ever experienced by armies took place on American soil; where more than 51,000 casualties accumulated like snowflakes during a winter storm as armed men fought to the death over political and moral issues that many of them didn’t bother to comprehend. The events that played out on this patch of land signified the turning point of the Civil War, which on a larger scale was a critical turning point in the history of our young nation. Before 9/11, everything we knew about this country could be categorized in terms of “before the Civil War” and “after the Civil War.” We were in arguably the most significant place in U.S. history, where tens of thousands of young men experienced the hellish and indescribable nature of warfare.

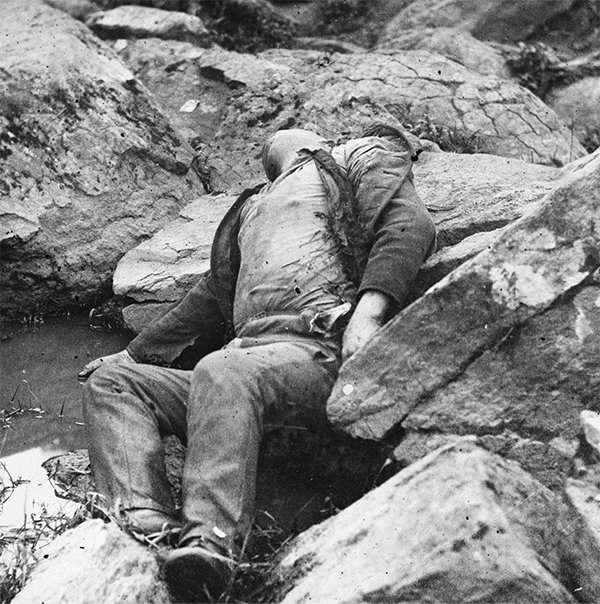

Dead soldiers from both armies were strewn all over Little Round Top. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The summit of Little Round Top—like the rest of the battlefield—is strewn with monuments dedicated to various individuals, companies, regiments, and corps. The fighting on and around Little Round Top on July 2, 1863, was both intense and strategically critical. Union Gen. Strong Vincent’s brigade held off wave after relentless wave of Confederate assaults as a number of Alabama and Texas regiments from Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood’s division attempted to flank the Army of the Potomac. Chamberlain’s Twentieth Maine successfully defended the end of the Union line on the southern slope (the extreme left), with the engagement culminating in a dramatic downhill bayonet charge that essentially ended the Southern advance.

The significance of this action cannot be overstated: If Chamberlain and his men had faltered that day, Southern forces would have flanked the Union left and crushed the Federal army in a rout. Instead, the failure to break the Union’s defensive line forced General Lee into attempting an ill-advised assault (Pickett’s Charge, see chapter 22) on the Union center the following day, which led to a devastating Southern defeat and the end of the Battle of Gettysburg. Many historians believe it also marked the beginning of the end for the Confederacy.

Thirty years later, Chamberlain received a Congressional Medal of Honor for his conduct in the defense of Little Round Top. The citation read that he was awarded for “daring heroism and great tenacity in holding his position on the Little Round Top against repeated assaults, and carrying the advance position on the Great Round Top.” Col. William C. Oates of the Fifteenth Alabama, who lost his brother John during those series of charges, strongly believed that if his regiment had been able to take Little Round Top, the Army of Northern Virginia might have won the battle, and possibly marched on to take Washington, D.C. He concluded philosophically that: “His [Chamberlain’s] skill and persistency and the great bravery of his men saved Little Round Top and the Army of the Potomac from defeat … great events sometimes turn on comparatively small affairs.”

Union Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain received a Medal of Honor for his extraordinary heroism on Little Round Top. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

We finally came upon a small plaque that directed us to the spot where Chamberlain formed his defensive line, and we slowly made our way down a narrow path to the remnants of a line of earthworks. We couldn’t help but feel a profound sense of respect as we stood in the footsteps of hundreds of brave soldiers who never made it off Little Round Top alive.

Instinctively, we began to canvass the area. My fellow investigator, Sean, immediately headed down the slope on which Confederate forces had relentlessly attempted their uphill attack. As darkness began to fall, I found myself sitting on a rock along the Union line, contemplating what it must have been like to be one of Chamberlain’s men, facing a continuous onslaught of bullets. Two other investigators, Sean and Scott, were walking around taking temperature and electromagnetic energy readings.

“Very funny, guys!” Sean snapped suddenly.

I asked what in the heck he was talking about.

“Was that you, Scott?” Sean asked.

There was no answer, as Scott had walked back down the path toward the viewing station at the summit of the hill. Obviously, Sean believed Scott was trying to scare him.

Sean, now even more annoyed, continued, “That’s just not cool.”

I had to set the record straight. “Sean, Scott’s not here, and I’m sitting about twenty yards above you on a rock along where the Union defensive line formed. What happened?”

“Are you serious?” asked Sean in an obvious state of excitement. “Somebody just walked right passed me and breezed by my left side. I saw a guy walk right toward me and I thought it was Scott. It had to be Scott.”

Now he had my attention. “I’m coming down there. Don’t move.”

I moved quickly down the hill. As I hurried toward Sean, I heard the shuffling of leaves to my left, as if someone was scurrying along beside me … and then I heard rustling to my right. I stopped a few feet from Sean, becoming very still and observant. Sean stood frozen, as if paralyzed by some type of ray gun.

“Did you hear that?” I whispered.

“Yes … loud and clear,” said Sean. “What the hell was that?”

“I have no idea,” I answered. “What did you see?”

I listened for more footfalls on the slope, but heard nothing.

“I was walking along slowly, trying to get a feel for what it must have looked like to the Confederates attacking uphill, when suddenly I saw the shadowy figure of a man—who at the time I thought was Scott—walking from that tree [points to his right] toward me,” Sean started explaining. “I turned back around and suddenly felt as if somebody brushed up beside me, but there was nobody there. That’s when I assumed Scott was trying to rattle me.”

“Can you describe the figure?” I asked.

“The man looked to be about 5-foot-8, thin, and I could have sworn he was wearing a cap on his head,” he continued. “Not like a cowboy hat or baseball cap, but more like a kepi or bummer. I couldn’t make out a uniform, just the outline of the body and the small cap on his head. He was moving from right to left if you were watching from the bottom of the hill, and he was moving pretty fast.”

This was getting good, so I continued to ask for details. “You felt him brush by you?”

“Yes, like a breeze, but definitely a tangible feeling of somebody whisking by me,” explained Sean. “There was a real sense of urgency with this guy, like he was trying to get somewhere fast.”

“Frantic, like during a battle maybe?”

“Exactly. Like he was running for his life, but I feel like my movements precipitated his movements, if that makes sense.”

Union earthworks on Little Round Top at the time of the battle. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

I knew exactly what he meant, because when I rushed down the slope to get to him, we heard the shuffling on either side of me, like others were running alongside me. We stood for a few minutes, listening for any sounds, and straining to see in the low-light conditions. It soon became too dark, and we didn’t have any equipment with us, so we decided to call it a night and check into our bed and breakfast. As we walked back up the hill, we saw Scott walking down the path toward us.

“This place is amazing,” he said. “You can see a good portion of the battlefield from that viewing tower. Anything interesting happen here?”

Sean looked at me with a wry smile and said, “You have no idea, Scott.”

As we left the battlefield, I wondered if the spirits of the soldiers who died there could react to our actions as if the battle was still in progress. If we made any sudden movements, for example, would they instinctually—as a result of having become emotionally attached to the location—spring into action, fighting on that hill as if it was still a hot afternoon in July 1863?

In order to understand how phenomena like this can occur, we must first examine a few of the basic laws of biology and thermodynamics. First and foremost, the fact that everything in the universe is energy has significant relevance as it applies to the possible existence of ghosts. Science has confirmed that energy exists everywhere and when in motion creates an energy field that allows energy to be absorbed, conducted, and transmitted. Our bodies radiate, absorb, and conduct frequency waves of energy, and each of our senses works through energies at specific frequency bands along the electromagnetic spectrum. Most surprisingly, if we magnify the cells, molecules, and atoms of which we’re composed, we can see that at the most basic level we’re made up of subtle energy fields containing little, if any, matter. We aren’t merely physical and chemical structures, but beings composed of energy.

As such, let’s look at the first law of thermodynamics, which is an expression of the principle of conservation of energy, which states that energy can be transformed (changed from one form to another), but cannot be created or destroyed. Based on these principles, we can now make an educated assumption that a transformation—not the destruction—of energy occurs at the time of physical death. At this point, the second law of thermodynamics takes effect. This law states that energy is dispersed from a core source and radiates outward in a symmetrical pattern until “acted upon.” This happens as a consequence of the assumed randomness of molecular chaos, and it’s also where the final pieces of the puzzle with regard to the creation of ghosts remain unidentified.

The second law dictates that upon death of the physical body, human energies generally disperse in a natural manner. This suggests that fragments of our conscious (or subconscious) thought can—at least for a while—interact with the surrounding environment in which bodily death occurred. What if this energy is “acted upon” in a way that either slows down or stops dispersal altogether? A traumatic death, for example, could create a “shock wave” that affects energy in such a way as to bind it to a specific time and place.

If you consider ghostly behavior, it makes sense. For the most part, haunting phenomena tend to be fragmented in nature. You hear footsteps, see a shadow out of the corner of your eye, or hear a disembodied voice calling out your name … but whatever transpires only lasts momentarily. When sentient behavior manifests, it’s as if the ghost is suffering from dementia or some stage of Alzheimer’s disease. They exist in a haze, as if coherent thought is difficult. When you capture EVP, it’s usually a sound, a word or two, or in rare instances a short sentence. Examples of EVP we’ve captured over the years include “cold,” “mommy,” a giggle, the rebel yell, a bouncing ball, and a gunshot. The most complete sentence we’ve ever captured was, “Won’t you help me?” and the most compelling EVP I’ve ever heard from Gettysburg was, “I knew George Pickett.” Truly profound, but only four words, not exactly the Gettysburg Address.

The bouncing ball and the gunshot can be categorized as residual in nature, but when a form of consciousness seems to be present and interaction of some kind occurs, we’re left with more questions than answers. As it applies to what happened to us on Little Round Top, we can see how the scientific laws mentioned above might corroborate the existence of the shadowy figure and the rustling of the leaves on the ground.

Here’s one explanation of what happened: On July 2, 1863, soldiers die on Little Round Top. Their deaths are traumatic in every sense of the word. When their physical bodies expire, their energy fields survive and transform, dispersing in a random way into the environment. Because of the emotional and sudden nature of the transformation, the last conscious thought gets stuck, thus remaining in the moment it was created just before bodily death. More than fourteen decades later, we arrive at Little Round Top and start walking around. One of these fragments of consciousness recognizes—on a purely instinctive and reactionary level—a man (Sean) walking down the slope of the hill. This particular energy field springs into action as if the battle is still raging, brushing past Sean as either a comrade in arms or mortal enemy. Sean sees the shadowy figure of a man and feels him brush by his shoulder, but then the event stops. Sean calls out, and I start walking down the hill toward him. Other energy fields present on the hill also react, following me down as if participating in Chamberlain’s counterattack. I hear the rustling of leaves and twigs around me as I head down the hill. When I reach Sean, the ruckus around us stops. The paranormal event ends, and we leave the area having had our first paranormal experience at Gettysburg.

So what happened? Is it plausible that fragmented thought forms—which once existed in whole form as living, breathing human beings—still wander about the battlefield, reacting to their surroundings in a purely random and chaotic manner? This is only a theory, but a theory based in some part on accepted scientific laws. By simply continuing along a line of logic, you can easily come to the conclusion that, at the very least, consciousness survives death. What happens to us when we die can be debated, but the fact that we continue on in some form appears obvious to those who experience such events.