WITH MY JOB AT INVERNESS—A WONDERFUL CLUB and wonderful golf course—waiting for me the next spring, I guess I was a little nervous going out on the tour that winter of 1940. I certainly didn’t get my game going very quickly. For some reason I can’t recall, I skipped several tournaments early that year. I didn’t play at Los Angeles, Oakland, or the Crosby Pro-Am; I lost in the quarterfinals at San Francisco, and finished out of the money at Phoenix. Not a very good start.

Back then the tour was different than it is now. A lot of us pros drove from tournament to tournament in a kind of caravan, and right after Phoenix, which happened to end on my birthday that year, we all headed for Texas. Ben and Valerie Hogan and Louise and I liked to stick together, so we’d follow each other pretty closely on the road. You kind of had to do that, because if you had car trouble, it was good to have a buddy nearby to help you fix a flat or whatever.

There was a place in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where we liked to stop for lunch. They had the best tamales and chili we’d ever tasted, with real authentic Mexican flavor. One particular time, we decided to ask if we could buy some to take along with us. The waitress told us, “Well, the tamales come in a can, and they’re made by the Armour Meat Company in Fort Worth.” All four of us just looked at her. Then at each other. Somehow, those tamales had suddenly lost their appeal, and we never ordered them again.

On that same trip, the wives of Ed “Porky” Oliver and Harold McSpaden weren’t along, so Ed and Harold were driving together. It was a good hard day’s drive from Phoenix to Van Horn, Texas, where most of us stopped for the night. McSpaden drove pretty fast, but Oliver was a lot more cautious. They were going along down this two-lane road and had to go through a tunnel at one point. Ed kept telling McSpaden to slow down, but Harold just kept saying, “I know this road like the back of my hand.” They got into this tunnel, and the tunnels then were always narrower than the road, and halfway through, barreling along at full speed, they met this fellow driving a wagon pulled by two big old mules. They just barely squeaked by, with McSpaden not slowing down hardly at all, and when they got through, Oliver yelled, “Don’t tell me you knew that wagon and those mules were going to be there, too!” I don’t know that they ever rode together after that, because it scared Ed pretty bad.

We all made it to Van Horn, including Oliver and McSpaden, and stayed at the El Capitan Hotel, which we always liked because they had wonderful hot biscuits and their food was very good. About dinnertime, we noticed that Oliver had disappeared. When he showed up about five hours later, everyone wanted to know where he’d been. He’d gone to a double feature movie the entire evening. Imagine—after sitting in a car from dawn till dark, he goes and sits in a theatre for four hours more. We couldn’t believe it. But it was all part of life on the road, and even though we had to do a lot of driving, we all stuck together and had a lot of fun.

As far as tournaments go, though, the first good thing I remember about that year was the Texas Open at Brackenridge Park. Ben Hogan and I tied at 271. I beat him in the playoff, 70–71, and broke 70 all four regulation rounds. It seems as if I played better against Ben on the average than I did against anybody else. I tried harder against him, because I knew I had to.

After we tied, we were told that a San Antonio radio station wanted to interview us. There wasn’t any such thing as a remote broadcast then, so they had to take us downtown to the station. I was asked how I felt about tying for the tournament and being in the playoff with Ben, and I said, “Anytime you can tie Ben or beat him, it’s a feather in your cap, because he’s such a fine player.” Then they asked Ben the same thing, and he said, “Byron’s got a good game, but it’d be a lot better if he’d practice. He’s too lazy to practice.” Ben never did think I practiced enough. But I did manage to beat him the next day, practice or not.

The next tournament was the Western Open at River Oaks in Houston. On the morning of the first round, my head hurt and I felt terrible. I shot a 78. The next day, I tried to play, because I hated to withdraw, but I shot 40 on the first nine and nearly passed out, and just had to quit. It turned out I had the flu and ended up in bed four days. I didn’t get the flu often, but whenever I did, it really laid me flat. Jimmy Demaret won the Western that year in a playoff with Toney Penna.

We went on to New Orleans, and I must have still been weak, because I finished fifteenth and won $146. I don’t remember much else about that week, except that we were staying at the St. Charles Hotel, and Louise and I were having breakfast in the dining room when she realized she’d left her aquamarine ring in our room. She went up to get it, but it was gone. We called in the manager and house detective and everyone, but it was never found. Louise was very upset about it. The ring wasn’t all that expensive, but I had brought it back from my trip to South America in ’37, and it had a lot of sentimental value for her.

The spring of 1940 was my first chance to play in the Seminole Invitational, one of the pros’ favorite tournaments. In the pro-am, if you won, you got 10% of the money in the Calcutta pool. The pros loved to get invited, because not only was it a wonderful golf course, but they had great food—a buffet every night that had more good food than any of us had ever seen before.

Next was the St. Petersburg Open. I made an eight-footer on the last hole for a 69, finished second to Demaret and won $450. Demaret was two years older than Ben and I, but he never would admit it until it was time for him to collect social security. He always claimed, in fact, that he was actually younger than we were.

In the Miami Four-Ball that year at the Biltmore Hotel golf course, McSpaden and I were partners. In the first round, we beat Johnny Farrell and Felix Serafin, 7 and 6, and then got trounced in the second round by Paul Runyan and Horton Smith, 5 and 4. They were a fine partnership team and outputted us that day. They were always wonderful putters, both of them.

In the Thomasville Open at Glen Arven Country Club in Georgia, I finished second again, this time to Lloyd Mangrum, though I broke 70 all four rounds. Next was the North and South, where I was defending champion. I finished second again at 2 under, won another $450, and lost to Hogan, who had two very fine first rounds and held on to win.

The Greensboro Open was played then at two courses, Starmount Forest and Sedgefield. I shot 68–68 the last two rounds and was third at 280. My philosophy at this point was not to have a bad round, and to have at least one hot round each tournament. I didn’t always do it, but that was what I knew I had to do to win or finish near the top.

Next was the Masters. Even then, just a few years after Bob Jones and Clifford Roberts started this wonderful tournament, it was a very prestigious one, and everyone coveted the title. I always loved going, seeing the flowers and Jones and Cliff. Just being at the Masters always got me excited and I nearly always played well there. That year, I finished third at 3 under and won $600. This was when the greens were not only as fast as they are today, but they were hard as rock, too. If you landed an iron shot on the green, it would bounce six feet in the air and roll off nearly every time. You couldn’t back the ball up no matter how much spin you put on it. Being able to back the ball up or land it on the green and stop it came about in later years.

Immediately after the Masters, Louise and I drove straight to Toledo. I was a little anxious about how I would do at Inverness. I felt I could handle it, but there were so many more active members compared to what I was used to. At Reading, I had less than a hundred sets of clubs to care for, and not all of those members were real active golfers. At Inverness, I had 365 sets of clubs, all quite active. I replaced Al Sargent, whose father was pro at Atlanta and had been Bob Jones’s pro when Jones was a young man. The golf shop at Inverness was in a separate building, about seventy-five yards from the clubhouse and right next to the first tee. In fact, it had been the clubhouse at one time. It was built when the original clubhouse had burned down years before, and served as a temporary clubhouse until the new one was completed. Then it became the golf shop. The caddies’ room was in the back, then there was my office, and then the shop itself. It was a nice building with high ceilings, though the shop was a little smaller than I would have liked.

One of the first things I did was to stock shoes. I brought in eighty-four pairs of men’s shoes, both street and golf, by Foot-Joy, selected with the help of my friend Miles Baker. Miles told me I was really the first pro to do this. Most pros would have sample pairs of different styles, but the members had to order them and then wait several weeks to get them. My eighty-four pairs covered all the styles in just about all the sizes and widths, which made it very convenient to sell the shoes on the spot.

Next, I talked to Mr. Carpenter and got his permission to put up an 8 × 8-foot square mirror on the wall across from the door. It not only made the shop look bigger, but when the weather was bad or I had time, I’d use that mirror to check my swing. When I had lessons scheduled during rainy weather, I’d put the students in front of that mirror and work with them, have them check their shoulder alignment, grip, stance, where they placed the ball, and so forth. It was really quite helpful.

When I arrived they gave me a locker upstairs, right where a group of the most prominent and influential members’ lockers were. That was a big help, because I got acquainted with them more easily. Another thing that helped me greatly was that Huey Rodgers, the caddiemaster, would stand at the door of the shop, and when he’d see the members coming from the clubhouse, he’d tell me who they were. That way, I got to know the members by name very quickly, and it impressed them that I could learn their names so soon—I don’t guess they knew Huey was helping me.

One of the first things I found to be different at Inverness was bookkeeping. At Reading, I had been fortunate in this regard. I just kept all the members’ charge slips and simply turned them in to the club bookkeeper each month. But at Inverness, it was a whole new world. It was so much busier, for one thing, and then I found I was expected to do my own bookkeeping, which naturally took quite a lot of time. Actually, I didn’t know how to go about it at all, and in about six weeks, I had all these boxes full of slips and charges and merchandise orders and no idea how to organize them. I was terribly confused. Finally I asked one of the members what to do, and he recommended Roy Bowersock, a fine CPA with the accounting firm Wideman and Madden, who got my books straightened out and taught me how to keep them myself. His firm was bought out by Ernst and Young some years later, and they moved Roy to Tulsa about the time I moved back to Texas in 1946. A year later, Roy was transferred to Fort Worth, and did all my bookkeeping and accounting for many years afterwards. I’ve been pretty good about it ever since—in fact, good enough to get me out of trouble with the IRS many years later.

About this time I was advised I needed to have an official domicile for tax purposes, and I figured Texas would be the best place, because it was one of the few states that had community property laws to protect Louise in case anything happened to me. It was also my home state, and Louise and I had felt for some time that if I ever left the tour, we wanted to settle near Fort Worth, because my family was all there and her sister Delle had married and moved there by this time.

Just as important to me was the fact that I’d wanted to do something for my folks for some time. They were living in Handley, Texas, and my father was running a feed store there. My brother Charles, about fourteen, was helping out, lifting those hundred-pound sacks of feed and doing the deliveries, but it was still awfully hard work for my father. He had bought the feed store some time before from Mr. Magee, the banker, with whom he’d become good friends. Magee was a widower, and talked my mother and father into moving into his home where my mother could keep house and cook for him, and they had lived with him for a few years. But I wanted them to have their own place.

We eventually found a fifty-four-acre farm for sale southeast of Denton. We bought it, and they moved there in October of 1940 and lived there six years. It was a good place for them. The farm gave both my parents plenty to do without overworking them, and made it easier for Charles and my sister Ellen to go to college as well. Louise and I never actually lived there, though it was my official domicile for tax purposes until I left the tour in ’46 and moved back to Texas permanently.

But back to Inverness and golf. Naturally, I was so busy those first few months that between the Masters and the Open, I only played in one 72-hole tournament, the Goodall Round Robin. It was at Fresh Meadow Country Club in Flushing, New York; I tied for sixth at plus 2 and won $300. Hogan played beautifully and won with plus 23. Besides being busy, my contract only allowed me to be gone six weeks out of the six months I would be at the club, so unless a tournament was close by that summer, I couldn’t play in it. The pros’ club contracts differed quite a bit back then. Some pros could go play in tournaments every week, and simply “played out of” a certain club rather than working there every day, while others worked a full week, like me. But I was enjoying my new job and the club a lot more than traveling on the tour, and making more and steadier money most of the time besides. I did play in one local tournament, the Ohio Open at Sylvania Country Club just northwest of Toledo. I shot 284 and won $250, but it wasn’t an official PGA event, so it doesn’t count on my record. But it served as a nice warm-up for the National Championship two weeks later.

The Open was at Canterbury Country Club in Cleveland that year, about a two-hour drive from Toledo. Not quite close enough to commute. I tied for fifth with 290, but felt very good about how I’d performed, all things considered. Lawson Little and Gene Sarazen tied at 287, and Little won in a playoff. The week after, I played in the Inverness Invitational Four-Ball. I was paired with Walter Hagen, long after the peak of his career. The sponsors then did everything possible to get more people to come watch the tournament, and in those days they didn’t invite just the players on the tour, necessarily. Hagen was in his fifties and playing no tournament golf at all, but they invited him to help draw more gallery. Because I was the host pro, they had me play with Hagen because it would have been unfair for the other players to be paired with him as his game wasn’t very sharp. We had to walk, naturally, and Inverness was a tough course, so it was a bit much for Hagen. The ninth hole there comes right by the side of the clubhouse, the tenth tee is at the men’s entrance to the locker room, and the 13th hole comes back to the clubhouse again. So after we played the front nine, Hagen would say to me, “Play hard, Byron, and I’ll see you at the fourteenth tee.” This was the only tournament I finished last in after becoming an established player (we tied for last, actually, at minus 14), but it was all for a good cause and it was fun to see Hagen play even then, so I didn’t really mind.

The PGA was at Hershey in 1940, but busy as I was at the club, I hadn’t played in a tournament for two and a half months. I was playing well, however, playing quite a bit with the members and giving lots of lessons. I had arranged in my contract with Mr. Carpenter that I could play in fivesomes with the members. What that meant was on Saturdays I’d go play a few holes with one foursome and a few holes with the next and so on. It was a good way for me to get to know each of the members, plus I could see what condition their clubs were in and how they were playing, and help them decide what kind of clubs, putters, new bags, or whatever they needed. It helped my sales in the shop, and it helped the members, too. They seemed to like it that I played with them.

About a month or more before the PGA, I started to get in shape for the competition by taking on three members at a time and playing against their best ball. They gave me a one-putt maximum on the first green, so I always started with par or birdie, but after that, I had to really play hard. We’d play once a week. These fellows all shot in the 70’s, and their best ball would be 65 or 66. It was tough competition, but I held my own and won most of the time. Some of the fellows I played with were Ray Miller, Eddie Tasker, Bob Sawhill, Alan Loop, and Tony Ruddy. A great group of golfers and good friends.

So I felt I was in good shape when I arrived at Hershey. I did all right in the qualifying and early matches, and made it to the semis without too much trouble. I remember how difficult it was for me to play in the semifinal against Ralph Guldahl, who was a wonderful player and a tough competitor, but who was also very slow and deliberate, while I played very quickly. I had to work at staying calm and not becoming impatient, and I managed to do it, fortunately. Then, in the final against Sam Snead, on the third hole in our afternoon round, Sam laid me a dead stymie* and thought he had the hole won. But I chipped over his ball with my pitching wedge and holed it and we halved the hole instead with birdies. By the time we reached the 16th tee, I was one down with three to play. On the 16th, I hit a good drive and a fine iron and holed a six-footer for birdie to catch up with Sam. On the 17th, a short par 4, you drove out on to a hill and pitched to a small green. I pitched three feet from the hole and made another birdie to go one up.

Then we came to the 18th, a long par 3, and it was my honor. I’ll never forget it. I took my 3-iron, almost hit the flag, and went about ten feet past the hole; I’d be putting downhill. Sam put his tee shot about twenty-five feet to the left of the hole and putted up close, so he had three. So all I had to do was make three to win the match one up. I coasted that putt down the hill very gently and made my three to beat Snead and win the PGA Championship.

As a nice sidelight to that victory, a couple of years ago I received a very kind letter from a man named Charles Fasnacht in Pennsylvania. He wrote that the boy who had caddied for me at Hershey had been a good friend of his, and when I sank that last putt to win, his buddy tossed Charles the ball and he had kept it all this time. He felt bad about it and wanted to send me the ball, but I wrote and told him that if it had meant that much to him to keep it all these years, then I couldn’t think of anyone who deserved to have it more.

That PGA was where the story got started about my so-called nervous stomach. Mr. and Mrs. Cloyd Haas came over when I had to play Guldahl in the semifinals. Mr. Haas had gone to the locker room with me before this 36-hole match, and while he was there, I lost my breakfast. He went right out and told Louise and Mrs. Haas. Louise said, “Good!” which Mr. Haas at first thought was very cruel, but he later found out that it was a good sign, because it meant I would play well. I didn’t do it all that often, but somehow the story got started in later years that this was why I left the tour. Actually, it was a little more complicated than that, which I’ll tell you about later.

A few other members from Inverness had come with the Haases—Hazen Arnold, Mr. Carpenter, the Bargman brothers, and several others, and after I won, I learned they’d made reservations for me and Louise to return to Inverness on the train that night. After dinner, they gave us a wonderful celebration party in the dining car on the way home.

I’d now won every major American tournament plus the Ryder Cup, but had not won the Los Angeles Open, which was considered a big tournament then. But I just didn’t feel yet that I’d completed my record. I wanted to win the PGA again, and had hopes of winning the national championship again as well. So I still had some golf to play.

The week after the PGA, I played in the Anthracite Open at Scranton and was second, with Snead winning. Then it was back to Inverness and no more tournaments until after I left the club in the early fall and went back to Texarkana. I finished the year well, though, winning the Miami Open and $2,537.50 at Miami Springs. I shot 69-65-67-70—271 and beat Clayton Heafner by one shot.

One thing I should mention about that year was how I got Cloyd Haas started in the golf umbrella business. Golf umbrellas then were about as bad as golf shoes had been before Foot-Joy started making them for me and McSpaden. Our umbrellas were flimsy, the cloth they used wasn’t waterproof and would leak, and if it was windy, the things would turn inside out and the ribs would break all to pieces.

Mr. and Mrs. Haas had taken Louise and me in like their own children, and we went over to their home for dinner quite often. Summers in Toledo were famous for mosquitoes, but they had a nice big screened-in back porch where Mr. Haas and I would go after dinner to sit and talk. We’d talk about first one thing and another, and one evening, I said, “Mr. Haas, you make such wonderful street umbrellas. Why couldn’t you make a good golf umbrella, too?” He said, “What kind of a golf umbrella do you need?” I told him, and he got to thinking about it. A few weeks later, I was at the Goodall Round Robin tournament in Fresh Meadow, New York. Mr. Haas was up there in New Jersey at the same time, visiting the factory he ordered his umbrella frames from, so he asked me to come out and meet him there. We talked with the manager about what we needed, and we settled on a double rib design and birdcloth for the fabric. They used my size to decide how big to make it, and it was quite adequate. Those first ones turned out to be a little heavy, but they were so much better than what we’d had before. I had mine made up in British tan and brown, and had one made for McSpaden in green and tan. When we brought them out to the course, all the boys wanted to know where they could get one, too. So Haas-Jordan got into golf umbrellas from then on, and theirs are still the finest, in my opinion.

I worked with Haas-Jordan for several years after that. Mr. Haas made me vice president of marketing, and each tournament I’d go to, I’d visit the large department stores—Neiman-Marcus, Macy’s, Bullock’s—and give them my card, and just introduce myself. I didn’t really do any selling, it was more of a public relations thing. But I got $25 for each call I made, which was nice, plus a generous bonus check each year, which was even nicer. Mr. Haas also had special ties made up for his staff to wear, with all kinds of different designs of umbrellas. I soon became known as “The Umbrella Man,” and it stuck for quite a while.

My connection with the Haas family continues to this day. I gave some lessons to Mr. Haas’s daughter, Janet, when she was just a college student, and she and her husband, H. Franklin “Bud” Waltz, became two of our dearest friends. Bud has been on the PGA advisory committee for many years.

I started to teach right away at Inverness, and found that I was teaching more of the better players now. I gave lessons almost constantly while I was at the club, and I enjoyed it. It was much easier to make the better players understand what I was saying, because they had a better grasp of the basics of the game.

One of the first good young golfers I met at Inverness was Frank Stranahan, R.A.’s son. He was quite an admirer of my accomplishments, and as he got better at his own game, he began to think he was as good as I was, which led to some interesting stories.

At one point, Mr. Stranahan had signed Frankie up for some lessons with me. Well, I soon found out that this young man wouldn’t listen to anything I had to say. He just wanted me to watch him hit balls, and wouldn’t change anything or take any of my suggestions seriously. After a few weeks of this, I told him, “Frankie, I’m not going to give you any more lessons. You won’t listen to me, and you’re wasting my time and your father’s money.”

Naturally, it didn’t end there. A few days later, Mr. Stranahan came into the shop with Frankie in tow, and said to me, “Frankie says you won’t teach him any more.” I was really on the spot. I certainly didn’t want to get Mr. Stranahan mad, because he was very influential at the club. But I had to tell the truth, too.

“Mr. Stranahan,” I said, “that’s not exactly what I said. Frankie won’t listen to me or change anything about the way he plays, and he’s wasting your money and my time. That’s why I told him I wouldn’t teach him any more.” Mr. Stranahan looked at Frankie and asked, “Is that true?” Frankie nodded and said, “Yes.” So Mr. Stranahan said to me, “If you’ll continue to teach him, I’ll make sure Frankie does what you say.” I agreed to give him another try, and he fortunately changed his attitude as well as his golf swing, and became a very fine player.

I had three assistants during my time at Inverness—Tommy Sullivan, Herman Lang, and Ray Jamison, who I hired from Ridgewood. Ray was an excellent golfer and teacher, and after I left Inverness, he moved on to be head pro at Hackensack Country Club in New Jersey, where he worked for many years. Herman Lang was a wonderful pro too, and was later hired to be head pro at Inverness until he retired and was succeeded by their present pro, Don Perne, also a fine man.

I had quite a few bad last rounds in ’40 that cost me some tournaments. I became conscious of this, and it wasn’t because I was nervous or choking or freezing up, but I gave some thought to it, and changed my philosophy. Regardless of whether I was behind or ahead going to the last round, I tried to really charge and go all out—not foolishly taking chances, but building myself up for the last round mentally. That’s why I began to play the fourth round the best later in my career.

1940 was a little like 1938. I had won four tournaments and added another major, the PGA, to my record, but I couldn’t expect it to be as big a year as ’39 had been. I was enjoying life in Toledo and my job at Inverness. I finished second on the money list, and I felt very fortunate. It was really a wonderful year, considering how little golf I played.

Louise and I left Toledo for Texarkana at the first cool spell, about the middle of September. I left my assistant in charge of the shop until it actually closed around the first of October. In December, we drove to Miami for the Miami Open again, which I managed to win for the second year in a row. That put another $2,537.50 in the bank, so my total winnings for the year, according to my little black book, were $9696. No, we weren’t having to borrow from Dad Shofner any more.

I went deer hunting that November in Uvalde, Texas, with Hogan, Demaret, and the new Winchester rifle I’d received from the folks at Reading the year before. I bagged a beautiful buck with a twelve-point rack of horns, but the game warden decided that since I had an Ohio driver’s license and Ohio plates on my car, my official domicile in Denton and my Texas hunting permit didn’t count, so he confiscated the deer and I had to pay an $80 fine. It really upset me, because I’d obeyed all the rules, but this fellow didn’t agree. And $80 was a lot of money in those days, especially for us.

Very few people today realize what it was like to be on the tour then. You didn’t make enough money even if you were a fine player to make a living or ever accumulate anything just playing in tournaments, so it was necessary to have a club job. Certainly, the better you played and more tournaments you won, the better your chances of getting a job at a fine club. Especially if you were toward the end of your career and wanted to settle down and not travel any more, having a good tournament record was a really big help. Being a good player also helped you get more lessons, because people thought if you could play that well you certainly should know something about the game and be able to impart your knowledge to your pupils. That wasn’t always true, because some of the touring pros didn’t ever spend much time teaching or become good teachers. The best teachers in my opinion were those who had taught themselves how to play, and who also had the ability to take it slow and easy with amateurs and be very patient. A top touring pro could also help increase membership and playing activity. Ridgewood was pretty full when I arrived, but Reading wasn’t, because there were a lot of golf clubs in Reading and it wasn’t that large a town, so my coming there after winning the Masters and then winning the Open two years later really did increase the membership. Inverness was always a famous club ever since 1920, when they held the U.S. Open there for the first time, so Inverness was also full when I arrived, but I did give quite a few more lessons than the pro before me had done. A couple of other examples of fine touring pros getting jobs at good clubs were Craig Wood at Winged Foot and Claude Harmon after him. No doubt their playing ability helped a great deal, in both their getting the jobs and helping to improve the clubs as well.

There were a few pros, like Hogan and Snead, who were registered at a club such as Hershey for Ben and Greenbrier for Sam, but who never worked there full time, really, though the club got the benefit of their names and the prestige associated with their wins.

But my situation was more like the rest of the fellows out there. I was very busy at Inverness and extremely happy there. I did enough traveling during the winter in California and the southeast that by the time the Masters was over, Louise and I were happy to get back to Toledo and spend the relatively cool summer there. Plus, I was making more money at the club—from salary, lessons, and shop profits—than I could count on making on the tour anyway.

Still, it was hard to keep my game in shape, and essentially, my golf suffered the first three years I was at Inverness. For instance, I started out 1941 pretty rough. Played badly the first two events, with a 302 at the L.A. Open and a 290 at Oakland, and just plain failed to qualify for the San Francisco Match Play tournament. Then I tied for fifth at the Crosby Pro-Am and for second in the Western Open at Phoenix Country Club. On the last hole, I hit a high 6-iron to the pin, which was cut fairly close to the front, over a bunker. I made that eight-footer to tie for second.

We pros always enjoyed playing in Phoenix, because Barry and Bob Goldwater would invite quite a few of us pros out to Barry’s house for a steak cookout during the tournament. This was long before Barry ever became Senator Goldwater. In fact, the two brothers owned Goldwater’s department store, a wonderful store which they ran quite well. The Goldwaters were very nice people—Barry was a natural leader, a good thinker, and good at speaking. Louise and I always looked forward to that party, and since I had won the tournament in ’39, I was on the list of invitees the rest of the time I was on the tour. This must sound at times as though all we pros thought of was our stomachs. The truth is, traveling the way we did, sometimes the food we’d get was all right, sometimes it wasn’t very good at all, and once in a while, it would be excellent. We’d all had enough lean times that we really appreciated good food when we could get it, and that wasn’t any too often.

The Texas Open was next, and that year it was played at Willow Springs in San Antonio, a tough little course. We had terrible weather, both snow and hail, but we went ahead and played in it. Lawson Little shot a 64 the final round—none of us could believe that—and I tied for fourth, mainly due to my putting. I had streaks of poor putting then; I remember after I’d played in the British Open, someone said that if I had putted well, I could have set a new scoring record. Well, that may be or may be not, but as I’ve said before, we didn’t work on our putting much because of the inconsistency of the greens. We concentrated on getting our approaches close to the pin, which was a lot more effective.

I didn’t do too well in New Orleans, either, tied for eighth. Then we went on to Miami for the Four-ball. My partner was McSpaden again, and again we lost to Runyan and Smith in the second round. Maybe that’s why Jug and I were called the Gold Dust Twins—because we didn’t get the gold, just the dust.

Next was the Seminole Invitational Pro-Am—not an official PGA event, but we loved the course and the food and loved to get to go. My partner that year was a fine amateur named Findlay Douglas. He was sixty-six years old and the 1898 National Amateur Champion. He still carried a 6 handicap, and he was a pleasure to play with. On the last hole, we needed a 3 to win, and a 4 to tie. Well, I made the 3, so that made Findlay pretty happy. Interestingly enough, though my winnings weren’t considered official, I did get $232.50 for my two rounds of 64-71, and $571.79 for my share of the Calcutta pool for a total of $803.29. Not bad pay for two rounds of golf, back then.

Then Louise and I headed back to Toledo so I could get things ready in the shop. The golf course wouldn’t really open until the middle of April, and there wouldn’t be much activity until after Decoration Day—what’s now called Memorial Day. But I needed to get things ordered and see that things would be running right when I did return after the Masters.

The next tournament was the North and South at Pinehurst. I played all right, tying for fourth, but had a bad last round of 76. I don’t remember what caused it now—sometimes it’s a blessing not to have a perfect memory. But the Greensboro tournament started the very next day, and I did better. I had a hot second round of 64 and won, so I was real pleased. A round of 64 can almost make you forget a 76. Another reason I was pleased to win there was that the weather was real bad, and the courses weren’t in good condition at all. Playing well in conditions like that gives you confidence. Of course, we pros didn’t complain about course conditions then—we were just glad to get to play.

You know, looking over my record for ’41, I’m surprised to see how many bad last rounds I had. It’s understandable that I didn’t win much until I got those last rounds turned around some. The next week at Asheville, North Carolina, I tied for tenth on a very hard course and never scored better than 72, though at the Masters I played very steady and finished three shots back of Craig Wood, who won.

Because my contract limited me to six weeks away from the club, I skipped the Goodall Round Robin in favor of playing in the U.S. Open, which was at Colonial in Fort Worth. They had put new sod on two greens and the course was in terrible shape. There had also been a lot of rain, which didn’t help anything. People didn’t know what to do then for golf courses like they do now, so we all just played and tried our best. I had another terrible final round of 77, tied for seventeenth, and won $50. You could say I was disgusted with myself. So the next few weeks I worked hard and finished second three times in a row, at Mahoning Valley, the Inverness Four-Ball with McSpaden, and the PGA at Cherry Hills.

A couple of interesting things happened at that PGA championship. I remember in my second match, with Bill Heinlein, I was coasting along through the front nine. Then all of a sudden he got hot and pretty soon I was 2 down going to the 13th. I managed to pull myself together and won 2 up. Next, I dispensed with Guldahl 2 and 1, and faced Hogan in the quarterfinal. I was 1-up going to the final hole. He had a fifteen-foot putt and I had a twelve. He missed his, I made mine, and that was the match. Remember, all of these were 36-hole matches, and the qualifier was thirty-six holes as well.

Next was the semifinal against Gene Sarazen, always a tough competitor. Fortunately I won, 2 and 1. Later he came over to me in the locker room and said, “Nelson, you double-crossed me.” Surprised, I looked at him and said, “How did I do that, Gene?” He said, “I’ve been playing my irons so well, I decided I’d let you outdrive me, then put my ball close to the pin and it would bother you. But you just put yours inside me all day!”

Next came the final against Vic Ghezzi, and one of the most unusual things happened that I ever saw or heard of in golf. I played wonderfully well the first twenty-seven holes and was leading 3 up going to the back nine. But I’d had such tough matches before this one, all of a sudden I just felt like all the adrenalin went out of me. I tried to fight it, but it didn’t do any good. After thirty-six holes Vic and I were dead even.

The playoff was sudden death. On the 2nd hole, we drove, then hit our approach shots close to the green. We both chipped past the hole about forty-six inches, and our balls were fairly close together, though mine was about a half-inch further away and his was about eight inches to the left. The referee, Ed Dudley, asked if Vic’s ball was in my way, and I said no. But when I took my stance, I accidentally moved his ball one inch with my foot. Well, of course, that was a penalty. In match play, it meant loss of the hole and in this case the match. Naturally, I conceded.

But Vic said he didn’t want to win that way, and there was quite a discussion. They decided that I should go ahead and putt, but I knew the rules. In my mind I’d already lost the match and knew it wasn’t right to let me putt. I didn’t want anyone ever to say I’d won by some sort of fluke. So of course I wasn’t concentrating real well and missed the putt, and Ghezzi won, which was only right.

The next tournament I played in was the St. Paul Open at the end of July. It was a six- or eight-hour drive from Toledo, so it was reachable. I tied for seventh and won $278. You see, I really did make more money at Inverness than I could count on on the tour. With my salary, all the income from my lessons, and shop profits, I did pretty well, with the exception of winning the occasional big tournament. This was why, with my commitment to Inverness, I had to pretty much concentrate on the majors and big money tournaments, because anything less would cost me time at Inverness, plus lesson fees and shop income. And if I didn’t play well, I could end up losing even more.

So I worked until the first week in September, when I drove to Chicago for the Tam O’Shanter. This was a new tournament put on by George S. May, a “business engineer.” That meant he advised other companies how to run their businesses. He was the first to put up a lot of money for a tournament. The first year, 1941, the first prize was $2000, the next year $2500, and it kept going up.

I played well in that first Tam O’Shanter and won the $2000. No, I didn’t make that much each week in the shop, but that was just one tournament of four or five that had big purses, and I sure couldn’t count on winning all of them. I always did well at the Tam, though. I wish the course were still there—it was turned into a development some years after George May died. The course was fairly hard, and the fairways were narrow. I played well there for two main reasons: one, it was a big money tournament so I tried harder, and two, I played those clover fairways well. Not that they planted the fairways in clover, but there was a lot of it on the course, and there were no chemicals to control it back then. Having learned to play on Texas hardpan, I always clipped the ball off the fairway and didn’t take much turf like some of the other boys. That clover had a lot of sticky juice if you hit very much of it, which would cause you to hit fliers. Fliers have little or no spin and you never can be sure what they’ll do, except it’s usually something you don’t want.

After the Tam, I played in a couple of little events near Inverness, the Hearst Invitational and the Ohio Open just outside Toledo, where I had a final-round 62, one of my lower scores in competition. Then Louise and I took our annual trip back to Texarkana. In December, we drove to Florida again, where I won the Miami Open for the second year in a row. That brought me $2000 prize money, plus an extra $537.50 in pro-am and low-round awards. It was a tough little course and the greens were stiff bermuda with a lot of grain. But in the practice round, I noted which way the grain ran on each hole, and most of the time, I didn’t pay as much attention to where the pin was as to which way the grain ran on that green and where I wanted to be when I putted. I was hitting my irons well, so I was able to place most of my approach shots where I would be putting downgrain, because that was the easiest putt you could have on that type of grass.

Right after Christmas, I played in the Beaumont Open and tied for seventh, then won the Harlingen Open with 70-65-70-66. The Beaumont course had the narrowest fairways of any course I ever saw. They were lined with trees, and Chick Harbert, who had trouble keeping his drives straight anyway, would tee his ball up as high as he could and hit toward wherever the green was. He’d say, “If I’m going to be in the trees, I’d rather be closer to the green.” Even as straight as I was, I had trouble staying in the fairways. They were the talk of the week.

I finished up 1941 playing in 27 tournaments, and my black book says I won $11,819.12, though Bill Inglish’s records say it was a little more, $12,025. The difference wasn’t enough to worry about, that’s for sure.

Of course, the whole year of ’41, there had been a lot of talk and worry over the situation in Europe, and we knew it was just a matter of time before the United States would get involved. Sure enough, that December we jumped in with both feet, and everyone’s lives changed almost overnight. Most people thought we’d lick both Germany and Japan in six months, come home victorious, and get on with business as usual—but of course, it didn’t turn out that way.

All of the men who were able to signed up for the draft, and then we tried to go about our business whatever way we could until our number came up. You know, it’s a good thing we really can’t see into the future, because if we’d been able to back then, I don’t think many folks could have stood it.

Starting out in ’42, I tied for sixth in Los Angeles, which kept the L.A. Open on my list of important tournaments I still wanted to win. Then in Oakland I did win, by five shots. This is how I did it: The greens there were quite soft, and all eighteen had a definite slope from back to front. I noticed that we were all hitting at the flag, and our balls were spinning back, sometimes off the green. I changed tactics after the last practice round, and aimed for the top of the flag. Then, when my ball spun back, it ended up closer to the hole. That’s the main reason I won. I remember the pro there was Dewey Long-worth, brother to my good friend Ted Longworth from Texarkana. He was a good player and a nice man, just like Ted.

Our next stop, the San Francisco Open, was played at the California Golf Club where my friend Eddie Lowery was a member. I played well but putted very poorly and finished eighth. I’ve already said that most of us pros didn’t spend much time on putting, because of the difference in the greens and so on, but I had another reason. I had originally learned to putt on stiff bermuda greens, where you had to hit the putt rather than roll it. I never really got over that, and I didn’t work on it enough because we tend not to work on things we’re not good at, and that certainly was true for me. I didn’t three-putt much, but my bad distance was eight to fifteen feet. Those were the ones I didn’t make as often as I should have.

Hogan won at San Francisco, though he was still hooking quite a bit then. On the 18th, which was a dogleg right, Hogan hooked a 4-wood high up over the trees and back into the fairway, because he just couldn’t fade the ball or even count on hitting it straight then. Though he hooked it, he used the same swing and did the same thing every time, so he got to be pretty consistent.

At the Crosby and the Western I didn’t do very well. I’d occasionally have several weeks when I wasn’t chipping or putting well, either one. But I practiced some, and by the Texas Open, I was doing better, finished eighth, then sixth at New Orleans, and second at St. Petersburg. Still couldn’t make much headway in the Miami Four-Ball, though—got knocked out in the second round again, this time with Henry Picard as my partner. But at least it was someone else beating us—Harper and Keiser instead of Runyan and Smith.

My game was getting better all along, but of course, so was everyone else’s. Our on-the-job training was working for quite a few of the players, from those who had loads of natural talent to those who had some talent and a lot of persistence. There still were no real teachers to go to like the boys have today. Most of the older club pros were still making the transition to steel shafts, or even teaching the old way of pronating and all, so they really couldn’t help anyone much. We had to figure things out on our own for the most part, and some fellows were better at it than others. But it was getting more and more important to have most of your rounds under 70, if you wanted to have a chance to win.

After Miami, I played in the Seminole Invitational again, enjoyed all their good food and being with the other players, and won $50. Well, at least the food was free, there was no entry fee, and my caddie only cost $8, so I had $42 more when I left than I did when I arrived.

I did better in the North and South, but had a bad last round of 73, tied for third, and won $500. At Greensboro, I had another poor last round of 74 and tied for fourth. Back then, they sometimes had prizes for low round of the day, and I tied in the third round with a 68, so I got another $25. Then I finished third at Asheville, and won $550. In my last five tournaments, I’d finished second once, third twice, and fourth once. I was definitely getting steadier, despite final rounds I wasn’t very happy with.

During that Asheville tournament, I realized there hadn’t been any pictures or publicity about me. It seemed the articles were all about the other players. I figured the press had gotten tired of writing about me, and I had gotten just enough used to all the attention that I kind of missed it. Anyway, about the third round, I was playing just so-so and was tied for the lead or leading. On the 16th hole, I put my ball in the left bunker, which was over six feet deep. I got in there and was trying to figure out how to get out and close enough to one-putt, and stuck my head up and looked over the bank to see the pin. Right above the bunker, on the green to my left, was a photographer, getting ready to photograph me as I played my shot. I said to him, “Where have you been all this week? Just get out of my way!” I did get up and down, but I felt bad about what I’d said, so I looked the fellow up afterwards and apologized, and he said, “That’s no problem, I shouldn’t have been where I was.”

Along about this time, McSpaden and I were on a train together, talking about the money to be made on the tour. We figured then that with an interest rate of about 10%, if we could make $100,000 during our careers, we could retire and live quite comfortably on that annual interest of $10,000. That seemed quite reasonable at the time, but it’s a ridiculous idea now.

Next was the Masters, but before the tournament started, I played a match there with Bob Jones against Henry Picard and Gene Sarazen. We were all playing well that day, including Bob, and on the back nine, Henry and Gene made seven straight birdies—but never won a hole from us. Jones shot 31 on the back nine that day. Amazing.

Then the tournament began, and fortunately, I played very well, ending the first round with 68. Paul Runyan led nearly the whole first round, and ended up tied with Horton Smith at 67. Sam Byrd was tied with me at 68, and Jimmy Demaret was behind us with 70. The second round, Horton led by himself for one hole, then I tied him with a birdie at the second hole. It was kind of huckledy-buck between Paul, Horton, and me for the next five holes, but I pulled ahead of them both with a birdie at the par-5 eighth. I was leading then for the rest of the second round, when I shot 67, and all through the third, but lost a little steam in the fourth when I bogeyed six, seven, and eight. Hogan had caught up with me when he birdied the eighth himself. He was several groups ahead of me, of course, so I couldn’t see how he was doing. I birdied 9 to lead again, and led till the last hole despite bogeying 17.

When I stepped up to hit my drive on 18, I noticed the tee box was kind of soft and slick. As I started my downswing, my foot slipped a little and I made a bad swing, pushing my tee shot deep into the woods on the right. By now I knew Ben had shot 70, and I had to have a par just to tie. When I got to my ball, I was relieved to find I had a clear swing. The ball was just sitting on the ground nicely, and there was an opening in front of me, about twenty feet wide, between two trees. I took my 5-iron and hooked that ball up and onto the green fifteen feet from the pin and almost birdied it—but I did make my par. So you can see why I felt very fortunate to tie.

Then came the playoff. This was one of the rare occasions when I was so keyed up my stomach was upset, even during the night. I lost my breakfast the next morning, which I thought might be a good sign, because I had always played well when I became that sick beforehand, and it always wore off after the first few holes. When I saw Hogan in the clubhouse, he said, “I heard you were sick last night,” and I said, “Yes, Ben, I was.” He offered to postpone the playoff, but I said, “No, we’ll play.” I did have half of a plain chicken sandwich and some hot tea, which helped a little, but you can see in the picture that was made of Ben and me when we were on the first tee that I was very nervous and tense.

This was probably one of the most unusual playoffs in golf, in that at least twenty-five of the pros who had played in the tournament stayed to watch us in the playoff. I don’t recall that ever happening any other time. Ben and I were both very flattered by that.

Flattered or not, though, I started poorly. On the first hole, I hit a bad drive into the trees and my ball ended up right next to a pine cone, which I couldn’t move because the ball would move with it. On my second shot, the ball hit more trees in front of me, so I ended up with a 6 while Ben made his par. We parred the second and the third. Then, on the fourth, a long par 3, I thought the pin was cut just over the bunker, but my long iron was short and went in the bunker, so I made 4 while Ben made 3. We’d played four holes and I was 3 down.

The 5th hole had a very tough pin placement at the back of the green, but we both parred it. The par-3 6th, I began to come alive a little and put my tee shot ten feet away, while Hogan missed his to the left and made 4. I put my ten-footer in for birdie, so I caught up two shots right there.

We both parred the 7th. Next, I eagled 8 and Ben birdied, so now we were even. I picked up three more shots on the next five holes, including a shot on 12 that rimmed the hole and stopped six inches away. But Ben didn’t get rattled much. Though his tee shot stopped short on the bank, his chip almost went in for a 2.

Byron Nelson, about eight months old.

At age 5 ½.

Byron with his mother, Madge Nelson, and her parents, M.F. and Ellen Allen.

Byron in 1934.

Louise Shofner Nelson.

Louise and Byron on their wedding day in 1934, leaning against Byron’s 1933 Ford roadster.

Byron leading in the first round of the Texas Open at San Antonio’s Brackenridge Park. He finished second behind Wiffy Cox.

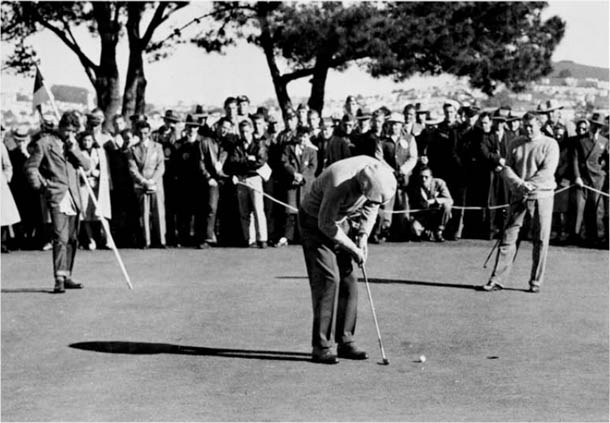

Byron playing Lawson Little at San Francisco’s Presidio in January 1935.

Taking a lunch break on the final day of the 1936 Metropolitan Open, which he eventually won.

A locust swarm during an exhibition at the Jockey Club in Argentina in 1937. After 3 holes the match was called off.

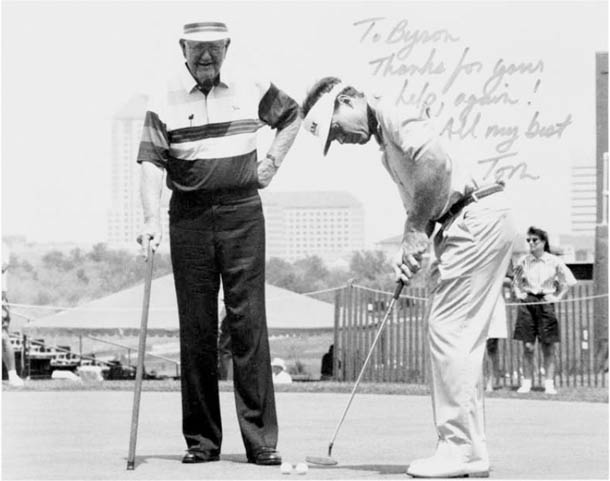

Byron with winner Tom Watson sometime in the late seventies at the Byron Nelson Classic . . .

. . . and in May 1992 at the same event.

A publicity shot taken in 1981 at Augusta.

Byron and wife Peggy at a local charity tournament in 1992.

Vice president Dan Quayle, Sam Snead, Gene Sarazen, Peggy Nelson, and President George Bush watch as Byron putts on the White House lawn in May 1992.

The 1992 Masters Champions Club Dinner. First row: Byron, Tom Watson, Gene Sarazen, Jack Stephens, Ian Woosnam, Henry Picard, Herman Keiser, Sam Snead. Second row: George Archer, Nick Faldo, Doug Ford, Gay Brewer, Billy Casper, Bob Goalby, Art Wall, Ray Floyd, Bernhard Langer, Arnold Palmer, Seve Ballesteros. Third row: Ben Crenshaw, Craig Stadler, Larry Mize, Tommy Aaron, Sandy Lyle, Jack Nicklaus, Gary Player, Fuzzy Zoeller, Charles Coody.

Byron after shooting a course-record 66 at the 1937 Masters.

The 1937 Ryder cup team. Standing: PGA President George Jacobus, Ed Dudley, Byron, Johnny Revolta, Horton Smith, Henry Picard. Sitting: Gene Sarazen, Sam Snead, Ralph Guldahl, Denny Shute, Tony Manero.

Harold McSpaden (with seat cane) accompanies Byron on his way to victory in the 1939 U.S. Open in Philadelphia . . .

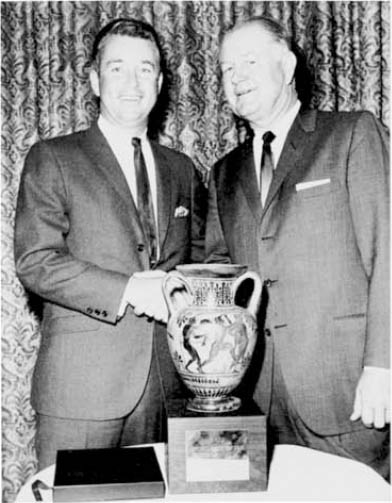

. . . and Byron accepting the trophy from USGA President Archibald M. Reid.

Teeing off at the 1939 PGA Championship in Flushing, New York. Byron lost to Henry Picard on the 37th hole of the finals.

A sand shot on the 7th hole on the way to winning the 1939 U.S. Open.

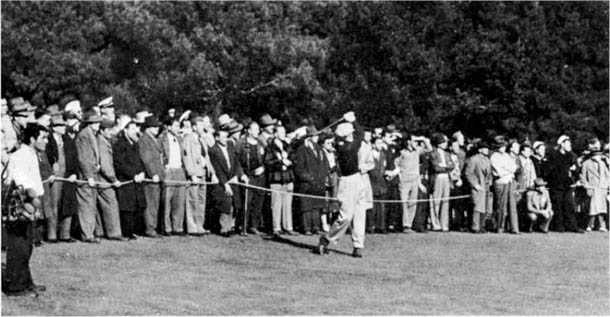

Sam Snead waits his turn at left as Byron drives from the third tee in the final round of the 1940 PGA Championship in Hershey, Pennsylvania. Byron won on the last hole.

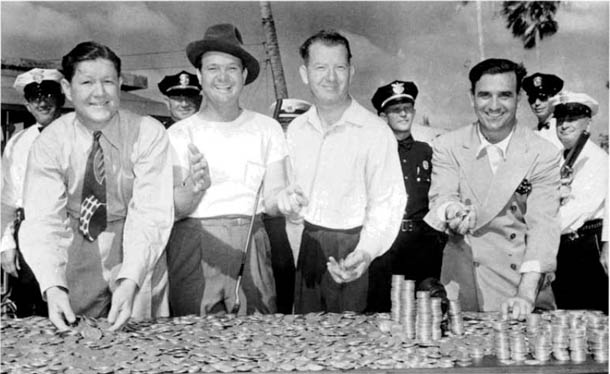

Byron, Jimmy Demaret, Jimmy Hines, and Tony Penna look over the $10,000 prize money at the 1940 Miami Open, won by Byron.

Playing in a 1941 exhibition match for British relief, Byron nearly holed out after Olin Dutra picked up his ball and placed it on a pop bottle lying nearby.

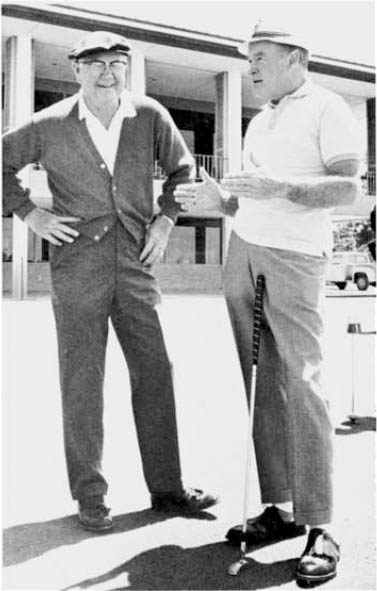

The Gold-Dust Twins: Byron with his longtime golfing partner, Harold McSpaden, in the early 1940s.

Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, Byron, Johnny Weissmuller, and Jimmy Demaret have a little fun in Houston during a wartime Red Cross/USO tour.

(Left to right) Ben Hogan, Byron, Bob Jones, and Jimmy Demaret at Augusta National Golf Club in 1942.

Playing out of the rough on the way to victory at the 1945 PGA Championship.

Celebrating a world record 259 at the 1945 Seattle Open.

At the 1944 Tam O’Shanter in Chicago, Byron holes one in a playoff win over Clayton Heafner.

Teeing off at the San Francisco Open in 1946. Byron won by nine.

Byron with his mother and father on his Denton farm in the early forties.

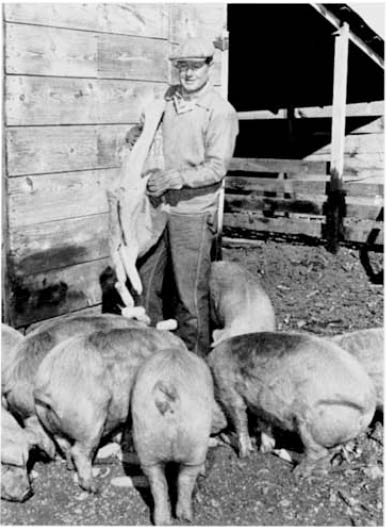

Feeding the hogs in Denton.

This Ford tractor from the 1940s is still running.

The Masters Champions for the first dozen years, excluding the war years: Horton Smith, Byron, Henry Picard, Jimmy Demaret, Craig Wood, Gene Sarazen, Herman Keiser. (Ralph Guldahl is missing.)

The 1947 Ryder Cup team. Standing: Dutch Harrison, Lloyd Mangrum, Herman Keiser, Byron, Sam Snead. Sitting: Herman Barron, Jimmy Demaret, Ben Hogan, Ed Oliver, Lew Worsham.

Byron putting in good friend Eddie Lowery’s office in San Francisco.

Byron with Babe Didrikson Zaharias in 1946.

Ben Hogan, Byron, and Herman Keiser at Augusta in 1946, just before the final round.

Byron and Louise with two half-Tennessee walkers presented to them by the mayor of Denton on the courthouse steps in 1946.

Byron receiving some tips from Ed Sullivan in the early fifties.

With Bob Hope at Pebble Beach in the late sixties.

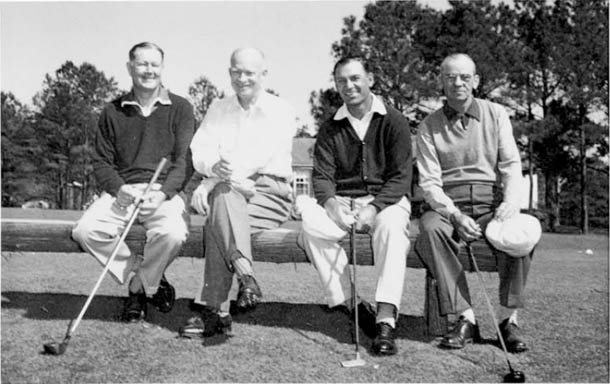

Byron with President Eisenhower, Ben Hogan, and Cliff Roberts at Augusta in the late fifties.

Arnold Palmer, Byron, Doug Sanders, and Gene Littler at the 50th anniversary of the LA Open in the mid-seventies.

Presenting Ken Venturi with the Sportsman of the Year award after he won the U.S. Open in 1964.

Byron with longtime ABC “Wide World of Golf” partner Chris Schenkel doing a Masters tournament broadcast in the early sixties.

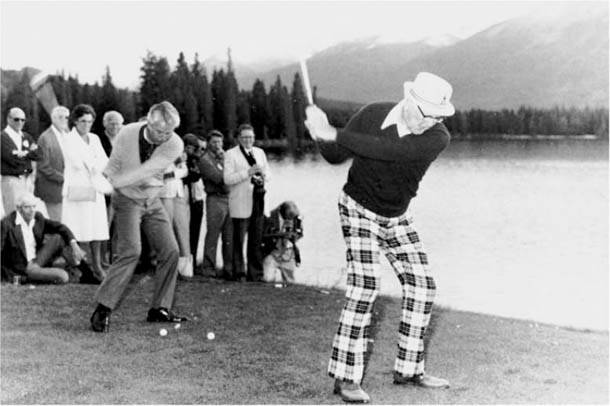

At President Ford’s tournament in Vail, Colorado. The president’s birdie putt has just lipped out.

Ken Venturi and Byron doing a clinic at Jasper Park Lodge in Canada in 1980.

When we arrived at the 18th tee. I was leading by 2, and Ben’s approach shot ended up way at the back of the green, with the pin way at the front. I played short of the green on purpose, not wanting to take a chance on the bunker, because in those days, a ball landing in the bunker would bury, and then you really had your hands full. But I figured I might chip up and make par, or no worse than 5, while I was pretty sure Ben couldn’t make his putt from up on the top ledge. I was right—he two-putted, I made 5 and won by one shot.

Louise and Valerie had stayed together up at the clubhouse during the playoff, and they were both very happy for me. Valerie was a very gracious lady, and Ben was always fine whether he won or lost. It was a great victory for me, and more so because I’d been able to beat Ben, who by then was getting to be a very fine player. The fact that he had come from well behind everyone else here showed that he had a lot of determination and persistence.

Then it was time for us to head back to Toledo and Inverness, where we stayed for six weeks before I played again. The PGA that year was at Seaview Country Club in New Jersey, and I was up against Jim Turnesa, one of the wonderful Turnesa brothers, in the semifinal. Jim was in the service, and naturally, the gallery was pulling for him, which I could well understand. I was 1 up when we came to the 18th hole, and I was short of the green, but chipped up two feet from the hole. Jim putted his stone dead and I gave it to him. The gallery gave him a tremendous round of applause because he’d played so well, and I thought it was one of the nicest things I’d ever seen a gallery do, to applaud like that when they thought he’d lost. I felt I had taken enough time over my putt, but maybe I hadn’t waited long enough for the noise to die down and lost my concentration. Anyway, I missed my putt, so we were tied. On the first playoff hole I hit a terrible drive and pulled it into the sticks. I made bogey, so Turnesa won, but ended up losing in the final to Snead. I was very disgusted with myself, feeling I’d just thrown the match away.

Back home, the Inverness Four-Ball was two weeks later, and my partner was Jimmy Thomson. We made a pretty good team, because I was playing well generally, able to make pars most of the time, and he was a good partner because he was so long. I’d hit a good drive and he’d be twenty to forty yards ahead of me. We managed to finish fourth and won $454.

The next week was the Hale America Open at Ridgemoor in Chicago, where I finished fourth and won $475. I skipped the Mahoning Valley tournament the next week in favor of the Tam O’Shanter again, and managed to win it—but just by the skin of my teeth. I was leading by five shots going into the fourth round and playing very well in beautiful weather. It seemed I had the tournament won, though I certainly didn’t feel that way. Anyway, on the first hole, I left my approach shot short and the green had a ridge on it with the pin on top. I three-putted for a 5. On the second hole, I hit an excellent drive that landed in a divot. But it was sitting all right and I was sure I could reach the green in two, though there was a creek just in front. Well, I hit it thin, it went in the creek, and I three-putted for a 7. The 3rd was a par 3 with a lake in front of the green; I hit a 6-iron that landed on the edge of the green but rolled back into the water. I’d made one bogey and two doubles, and was five over after three holes. I was out in 42—just terrible. But I pulled myself together and played the back in 35, which put me in a tie with Clayton Heafner after starting the day five shots ahead of the field. You think I don’t feel for the boys today when the same thing happens to them? I surely do.

We had the playoff the next day—all playoffs were eighteen holes in medal tournaments, and there were just about as many playoffs then as there are now. But the beautiful weather had gone—it was windy, rainy, and miserable. However, I was steamed up enough to play well, shot a 67 to Heafner’s 71, and won the Tam again. That was a good comeback for me, particularly because of the way I’d lost in the PGA just a few weeks before.

I won two other small tournaments that year, the Ohio Open and the Charles River Invitational, but neither of them were official events, so they don’t count on my record, though they were good experience for me, and it never hurts to win, even if you’re just playing a casual round with friends.

What did happen that year—in fact, the next month—was my professional baseball debut. Growing up, I liked to play baseball and was a good outfielder. At one point, I thought quite a bit about which one I wanted to concentrate on, and chose golf. But I still loved baseball and went to watch a game whenever I had the chance. In Toledo, that meant the Mudhens, a farm team for the St. Louis Browns. Fred Haney was their manager, and he and I had played golf some at Inverness. The Mudhens had an exhibition game coming up against the Browns, and Fred got the idea of having me play in it to get more people out to the game, which was going to benefit the Red Cross. He advertised it as “Golf Night,” and gave me ten days to practice with the team. I remember that catching the ball in the type of glove we had then was making my hand really sore. He told me I could fix it by sitting and tapping my palm with a pencil over and over to toughen the skin, and it worked.

In the practice sessions, I did all right on everything but batting. You just can’t believe how fast that ball went past the plate. You really had to be ready to hit before it left the pitcher’s hand, and I never quite caught on. Then they got me suited up, and Fred told me it was fortunate I was the size I was, because I wasn’t too hard to fit.

The game began, and I started in right field in place of a fellow named Jim Bucher. Milt Byrnes was the center fielder, and he said, “Byron, if you get the ball, just toss it to me and I’ll come running and throw it in,” because he knew I’d have trouble throwing accurately the distance to second or third or home. Well, the first thing you know, someone hits a grounder right at me. I scooped it up and threw it to second, which kept the runner on first and got me a big round of applause from the fans.

Then it was my turn to bat, and I whiffed. The fans started hollering, “Better stick to golf, Nelson!” and “Put Bucher back in!” Fred kept me in till the fourth inning, though, and then he said, “Byron, you’ve had enough fun, and I really would like to win this game, so I’m taking you out.” That was fine with me. So Bucher goes back in, and strikes out his first time at the plate. Now the fans start yelling, “Put Nelson back in!” And then when we took the field, Bucher tried to catch a fly ball and dropped it, which really got the fans yelling even louder, “Put Nelson back in!” It was a lot of fun for me, but not so much for Bucher.

There’s a good follow-up to this story, though. The Ohio Open was a few days later in Cleveland. Marty Cromb, the pro at Toledo Country Club, rode on the train with me to Cleveland, and was criticizing me severely for being so foolish as to play baseball. “You could have hurt yourself—broken a finger, ruined your career,” he said. When we got to Cleveland, we were met by a friend of his, Bertie Way, a Scottish pro. Marty got to telling Bertie how crazy I was to play baseball, and how it was going to hurt me playing in the tournament.

Well, Bertie got all fired up and went to see some buddies of his, making bets against me, even though I was the favorite. We had no time to play a practice round, so I went out when the tournament started, scrambled around on the first hole and made par, scrambled again on the second, then settled down and started playing. To make a long story short, I birdied 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12, shot 63, and won the tournament. Bertie was so mad at Marty I thought he was going to kill him. He really thought Marty had set him up.

By this time the war was getting worse, and many of the pros were already in the service. It was becoming more difficult to put on tournaments, and at the end of ’42 the tour just plain stopped.

There would be no Masters or U.S. Open for the duration of the war, and none of the regular events were played for all of ’43. We did have just a couple of tournaments that had pretty good fields, but most of the boys were either in the service in some capacity or doing exhibitions for the Red Cross or war bonds.

Back in the spring of ’42, when the draft was in full swing, I’d had a conversation with Colonel Woolley from the artillery training base at Camp Perry, near Toledo. He had played golf with me several times and thought I had a great eye for judging distance. He knew I had registered for the draft, and wanted me to let him know when my number was coming up, because he wanted to get me to teach his men how to judge distance. I went down to enlist soon after he talked to me, but I failed the physical because of my blood condition. It was not hemophilia, but what was called “free bleeding”—my blood didn’t coagulate within the normal amount of time. Later that year my number did come up, and I failed the physical again for the same reason. They could have put me in a desk job of some sort, of course, but I still would have to go through basic training, and the Army didn’t want to take a chance on me getting hurt out in the field and not being able to get help soon enough. After I failed the physical the second time, they didn’t call me any more. So I was out of it. McSpaden was rejected too, because he had severe allergies and sinusitis. So there we were, looking as healthy as could be, but not in uniform like the rest of the boys. It was an uncomfortable feeling, believe me.

But it wasn’t too long after we were rejected that Ed Dudley, who was president of the PGA then, asked if we could do some exhibitions for the war effort, visiting rehab centers and so on. He and Fred Corcoran, who had been managing the tour, wanted golf to do its part. So Jug and I began in late ’42 and did exhibitions all through ’43 and part of ’44. David Fay, president of the USGA, told me recently that we did 110 of them, traveling back and forth across the country. We actually criss-crossed the United States four times doing Red Cross and USO shows, and going to the camps where they had rehabilitation centers for the soldiers. A lot of the camps had putt-putt courses and par-3 courses for the boys. Sometimes we’d go on military planes, sometimes on trains. We got no money, but MacGregor helped pay my expenses and Wilson paid some of McSpaden’s. The people at Inverness really supported me during that time too, making sure my shop was being run right while I was gone.

We started in the early spring, working with the Red Cross and the USO to help the boys’ morale. There were very few golf facilities, so we didn’t do a lot of exhibitions, but we did visit the hospitals and camps and shook hands with the soldiers and told them how much their sacrifices meant to us and to the whole country. Most of the patients were ambulatory, so when there were golf facilities available, we’d show the soldiers the fundamentals of grip, stance, and so forth, or hit some drives and other types of shots to demonstrate the basics. One time we went to a camp near a rocket-testing site in New Mexico, I believe, and they shot off a few rockets for us to see. It was impressive—and scary.

Because of all the gas rationing, we traveled on restricted types of orders. We’d be put on troop trains or planes where they’d always feed the servicemen first, which was only right. We weren’t neglected, you understand—just hungry a lot. Once, I remember they ran out of food before they got to us, so when we stopped at a little station near El Paso, Jug and I jumped out and ran in to see if we could get a sandwich. Well, the man said, “These are for the soldiers,” but after we explained what we were doing and why we were on the train, he finally let us have one sandwich apiece.

It was tougher on McSpaden than on me in a way, because he really did love to eat and could eat a lot more than I could. Once, in Seattle, we stayed at a hotel and at breakfast, McSpaden had half a cantaloupe with ice cream, ham, eggs, toast, and tea. I had what you’d call a more normal breakfast. When he was done, he asked the waitress to bring him another half cantaloupe with ice cream. The waitress said, “Are you kidding?” and Jug replied, “That’s what I ordered, isn’t it?” She brought the cantaloupe, put it down on the table very carefully, and then backed away like she was expecting him to explode any second. That fellow really could eat.

On the trains, once in a while we’d have a berth to sleep in, but mostly we just slept sitting up like a lot of the soldiers. Even though we were pretty young ourselves, most of the servicemen seemed like kids away from home for the first time. But their morale was quite good. I’d have to say the whole experience was enjoyable for us, but very tiring with all the travel, and it wasn’t easy to see those young boys going off to war or coming back all busted up.

In the middle of July, we did have a tournament called the All American, played at George May’s Tam O’Shanter course. The purse was $5000. I tied for third, thanks to a final-round 68, and won $900. I was one shot back of McSpaden and Buck White, a pretty good player who wasn’t around too long on the tour. McSpaden beat Buck in the playoff. In August, I played in the Chicago Victory Open. I started off with a 68, then did three 72’s in a row and finished fifth. I didn’t win any money because they paid only the first four places. Then there was the Minneapolis Four Ball at Golden Valley, which I played with McSpaden. We finished second at plus 8. They also had the Miami Open in December, but I didn’t play in it, most likely because I was doing an exhibition somewhere to raise money for the war or the Red Cross.

I did, however, play in and win the Kentucky Open that year. It was played at a course called Whittle Springs, and I remember it well because I was presented with my winning check by Sergeant Alvin York, the much-decorated hero of World War I. That was quite an honor for me.

We also had sort of a substitute Ryder Cup tournament that summer, called the Ryder Cup Challenge. I was selected to be on the Ryder Cup team, and Walter Hagen captained the “Challengers.” We played at Plum Hollow in Detroit. McSpaden and I tied Willie Goggin and Buck White in the foursomes, plus I beat Goggin in the singles, 4 and 3. We beat Hagen’s team overall 8½–3½.

Sometimes we’d pick up other people who’d play these exhibitions with us—people from golf or the entertainment field like Bob Hope or Bing Crosby. We didn’t always play eighteen holes, usually only nine, but they’d build a platform near the clubhouse at whatever course we were at, and whoever was in charge of raising the money for the Red Cross or selling the war bonds would get up on the platform, and it would be almost like an auction. A man would say, “I’ll give ten thousand dollars if Bing will sing ‘White Christmas.’ ” Or “I’ll give five hundred if Hope will tell a joke.” We’d raise tens of thousands that way. It was exciting at times, and I really believe we contributed more to the war effort that way than if we’d been accepted for service. Another benefit was that it kept my game in tiptop shape for when the war was over and the tour started again. Fortunately for some of the pros who were in the service, they had the opportunity to play quite a bit, too. Sam Snead was in the Navy, stationed at La Jolla, California, and he played nearly every day with the admirals and such. Horton Smith, Ben Hogan, and Jimmy Demaret also had quite a few opportunities to play—not just at the bases where they were stationed, but in whatever tournaments there were, too. By the end of ’43, we’d played at quite a few camps where our fellow pros were stationed. So despite the fact that the tour was canceled, we did get to see the fellows from time to time and play with them a little.

Once we did nineteen days in a row with Hope and Crosby, who were great. Bing would sing and Bob would tell jokes, and the crowd loved it. They were both just as you imagine them, born entertainers. Bob was always telling jokes, and Bing was quick-witted, too, plus he was completely natural at all times. The people loved them both. On one of these stops we were staying at a hotel and to avoid the crush of autograph seekers they ushered us in through the back door and up the elevator. But some of the fans had seen the elevator going up and where it had stopped, and they all trooped up six flights of stairs to our floor. Bob and Bing were so impressed with the fact that these kids would climb all those stairs just for an autograph that they signed every single one of them.

One other time, I was with Hope and we were on an Army plane. Sometimes there wouldn’t be any seats—we’d sit on a bucket or a box or just on the floor. Anyway, they had picked us up in Alabama and we were going to Memphis. Ed Dudley was going to meet us and we were to put on a show there. When we landed, the runway was very narrow, plus it had rained a lot, the ground there was very muddy, and the plane slipped off the runway and into the mud up to its hubcaps. It took forty-five minutes for them to get a vehicle big enough to pull that plane out of the mud. But we got there and did the show just a little late and everyone seemed happy.

I did have one pretty scary experience during this time. I was with Bing Crosby in San Antonio, and a man picked us up at the train station and took us to an army base—I don’t quite remember which one—where Bing was to perform. There were a lot of restrictions then, and when we arrived at the gate, there were two sentries with rifles guarding it. But this fellow who’d picked us up just drove past them without even stopping. There was another pair of sentries a little further on, and when they saw us drive past the first sentries they immediately raised their rifles and ordered us to stop. I was in the front seat and Bing was in the back, and when we saw those rifles go up, Bing hit the floor and I ducked as best I could. We truly thought we were going to get shot at. Of course, the driver had to stop then and explain who we were and what we were doing there, and they finally did let us through, but they really gave that fellow a tongue-lashing for not stopping at the first gate. And you know, that man never did even apologize to us. Just acted like nothing had happened at all.

I’ve been asked whether we got much criticism for not being in the service, and I have to say we got far less than I expected. Mainly, I think it was because what we were doing for the war effort with our Red Cross and USO exhibitions and so forth got plenty of publicity, and every write-up that I can recall was sure to mention that we had been rejected for military service for physical reasons. We were fortunate to have that kind of positive press; there were plenty of other men who had also been refused for physical reasons that no one else could see who were unfairly criticized.

The only complaints I did get were about gas rationing. I was still the full-time pro at Inverness all through 1944, but because I had to travel so much to do all these exhibitions, I needed more gas stamps than most people. Fortunately, I was able to get them without too much difficulty, because the people in charge of the various exhibitions would take care of it for me most of the time. But sometimes people would see me driving along here and there and think I was doing something wrong. Once the rationing board called me in about it because a man in Toledo had complained, but when I explained what I was doing and showed them my stamps, which were all legal and proper, they said it was all right.

Naturally, Louise couldn’t be with me on any of these Red Cross or USO exhibitions. She mostly stayed at her folks’ place in Texarkana, her sister Delle’s in Fort Worth, or else in Denton at the farm I’d bought for my parents in 1940. It was a difficult time for her, and I sure didn’t appreciate the separation myself, but fortunately it didn’t last forever.

By 1944, the tour was alive again with twenty-three events, not quite as many as there had been before the war. Still, many of you who read this will be surprised that there were even that many. I was, too, really. The PGA had used golf in any way they could to help the war effort, but the people interested in golf had reached a point where they were hungry for news of any sports, including golf. Ed Dudley and Fred Corcoran deserve a lot of credit for not only what they did during the early war years, but for getting the tournament back on its feet again in ’44. Many of the tournaments in ’44 were renewals of ones that had been going on before the war, but a few were new ones, and some of the older and bigger ones still weren’t back in operation, including the Masters and the U.S. Open. What Louise and I were happiest about was the fact that we could travel together again. McSpaden was okay as a traveling partner, but I definitely preferred Louise.

As I said earlier, my game was in good shape because of all the work I’d done during 1943, so I started out in ’44 with some good pro-ams. We still played pro-ams then with just one partner and used no handicaps, which meant we always got good partners. Just like today, your partner would be someone who had helped sponsor the tournament. Anyway, at the pro-am at Hillcrest I won with 65. Then I won with 67 at San Gabriel Country Club in Los Angeles, and with 64 in Phoenix.