Readings

from Principles of Necrophysics: “A Report on Certain Curious Objects, Believed to Be Words in an Unknown Language of the Dead”

For a long time the Founder believed that the cosmos had just two parts, life and death, pressed together like two palms in prayer.

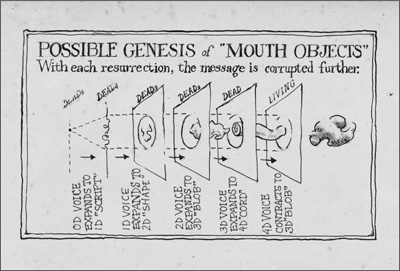

However, toward the end of her life, something began to happen that put this simple model into question. She—and, not long thereafter, some of her more talented students—began to cough, spit up, or find on the pillow in the morning those waxy, lumpen articles known today as ectoplasmoglyphs or, familiarly, glyphs, e-glyphs, or just “mouth objects.”

What were they? The dead were evasive when asked, and appeared uneasy with the topic. The Headmistress, in one of those intuitive leaps characteristic of her, decided that they were words, messages from a more corporeal realm of the dead. Where was this realm? Perhaps the dead also die, passing from their own plane to a yet deeper one. Death and life are not opposites, then, but graduations in a series. Thus it was the mouth objects that supplied the first and best clue to the complex structure of the necrocosmos. Yet in many ways they remain as great a mystery as when they were first documented.

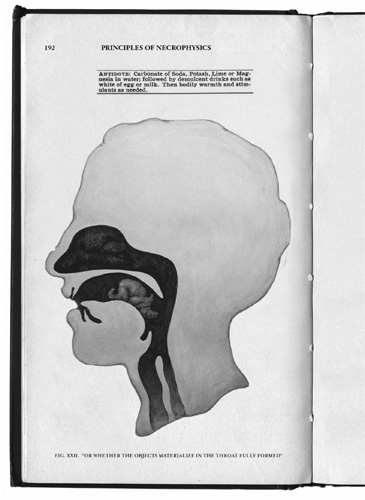

Ectoplasmoglyphs are translucent, waxen in appearance, gummy but firm in texture, and something between animal or vegetable in form, so that they really appear, not modeled by conscious art, but grown. We are lucky to have a description of “parturition” in the Headmistress’s own hand: She describes a stirring in the throat, then an “intricate rippling, gathering, pleating, and revolving.” She wonders whether this “kneading” by the deep muscles of the throat, muscles rarely subject to our conscious control, is what shapes the ectoplasm, imposing form on something itself formless, or whether the objects materialize in the throat fully formed, and the activity observed there is merely a sort of peristalsis, moving them forward. With her usual perspicacity she has hit on exactly the point of contention that rocks lecture halls today; science has not advanced one jot since her time.

In a magnified slice of a mouth object, you can see the reticulated structures reminiscent of honeycomb tripe, or cow stomach, that some researchers have described, and that have strengthened the claim that these objects are not merely excretions or accretions of matter, like ambergris in a sperm whale’s intestines, but three-dimensional hieroglyphs—a little squashed, perhaps, but still displaying the features by which they would communicate to a viewer possessed of their secrets.

Incidentally, the widely circulated report that in one mouth object researchers found a baby tooth and some coiled hair is almost certainly apocryphal, inspired by those teratomas in which a sort of anagram of a baby seems to be trying to get itself born. If true, however, it would suggest that teratomas and perhaps all tumors are special dispatches from the dead. It is not actually such a far-fetched notion: we all carry messages from our forebears, scrolled neatly in our cells. Indeed, we arguably are such messages.

It is regrettable that some of the best-known depictions of mouth objects are the work of J. T. Giesel, once a highly respected science illustrator, but since fallen out of favor for the degree to which wishful thinking (if not the deliberate intention to deceive) colored his work. In his rendering, the lumpen and even—why not admit it?—rather fecal word has acquired a delicate tensile strength, like a bridge.

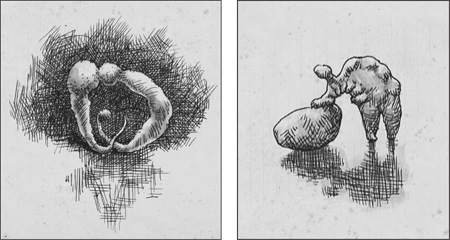

He is right, in one sense: The word is a bridge to the world of the dead—or to, I should say, another world of the dead. However, we should not so readily dismiss what is intimate, personal, and a little disgusting about mouth objects. Most things that come out of the human mouth are judged unclean. Speech is ordinarily exempt from this prejudice; we listen publicly to others’ words without a blush and even take them into our own mouths in mimicry or quotation. We have learned to unbuckle language from the gag reflex. It is our loss. The ectoplasmoglyph reminds us where the word comes from. Presented here, from the archives of the Vocational School, in an unknown hand, are some images of mouth objects over which no prettifying veil has been drawn.

Fig. XIX. “some images of mouth objects over which no prettifying veil”…

It is now generally accepted that these objects are indeed elements of a language of the dead. But questions remain. Are they the three-dimensional equivalent of logograms, in which representational elements can be made out in radically simplified form, as in the Japanese kanji? Are they composed of alphabetic elements, fused in a sort of three-dimensional script? Or do they, like the objects exchanged by the learned professors of the Grand Academy of Lagado, signify only themselves—in which case the task before us would be, not to determine what they mean, but to see what they are? (It is no small one!)

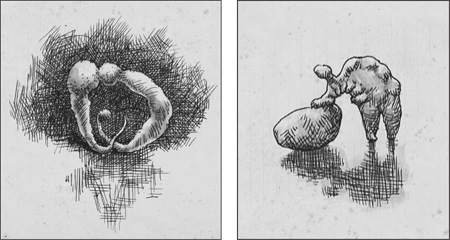

Do we even perceive them in their original form? Perhaps the once-featherweight word acquires mass through signal corruption in passing through successive regions of the dead. Perhaps a sort of Doppler effect shifts it farther along a spectrum of thingliness, the farther it goes.

Or perhaps these objects are a sort of pidgin, deliberately yet clumsily endowed with physical properties to establish rapport with a world where material things are held in high esteem. If so, they have largely failed, though it is true that students have found that some of these objects name new feelings for them, new thoughts, which once conceived cannot be described in other words.

Fig. XX. “a spectrum of thingliness”...

An understanding of the whole language, however, still eludes us. Scholars are cataloguing new words as they appear, in the hopes of discovering patterns that will unlock this language for the living. We at the SJVS would like to call all thanatomaths and interested amateurs to the work of translating these messages into English. Alternatively, some may wish to translate these objects into other material objects native to our world. We would also like assistance in translating our own languages into physical objects. Perhaps we can reply to these strange bulletins from the “dead dead,” if we learn their language.

The Founder was optimistic. “It may be that we already speak this language,” she wrote, “albeit not with our mouths.” After all, we too are material objects, ambiguously and temporarily haunted by voices. Able morticians and undertakers, we groom our corpses, daub blush on our cheeks, pink the lips. We look alive, but only for a little while.

Reasoning that they might communicate through any of their physical properties, not only their form, she performed many experiments on the objects: immersing them in water, then in distilled alcohol, heating and cooling them, rubbing them with wool, striking them with mallets. One word was given to a terrier to sniff, who was moved to urinate, another shown to an infant, who recoiled. One was allowed to air-dry until hard, ground fine, and mixed with ink. A greasy elastic pellicle formed on its surface, which the nib had some trouble piercing. The ink had the tendency to draw itself up into balls on the surface of the page and, when the paper was lifted, to roll away, leaving the paper perfectly blank in places. (This may be no more than a curiosity, but the portions of the text that vanished composed, without exception, pronominal forms and proper names.)

Fig. XXI. “to cough, spit up, or find on the pillow in the morning”...

Her account of one early experiment is worth quoting in full, and will conclude this brief report. “This evening I conducted tests on one of the words, though to destroy it seemed to me like savaging my own tongue. I first laid it on a glass tile I had wiped with rubbing alcohol. With a clean, very sharp knife I sliced it first longitudinally, then latitudinally. I noticed that I winced as the blade passed through the substance, which clung to it. I had to bring down the knife very slowly so as not to distort the word in slicing it. The cross-section revealed minute whorls and fault lines where the substance was whiter and more opaque, like wax that has been put under pressure. One part of the word I picked up with a pair of tongs and held over a low flame. This experiment was exceedingly distressing to me. I noticed with interest an increase in salivation; my mouth was flooded with sweet water. It would be interesting to try to determine whether this response is characteristic of all observers. The flame took all over the surface of the word, igniting with a soft pop. This flame very bright and mellow. The lump shrank without spattering or bubbling. I deduce from this that its substance is dense and pure. The effect was not unlike burning a candle of very fine wax, but brighter.

Fig. XXII. “or whether the objects materialize in the throat fully formed”...

“As the word shrank it performed several revolutions or convulsions too quick to follow with the eyes but disturbing and uncanny, especially as it seemed to me that it passed through several forms that were recognizeable and possibly of particular personal significance, through due to the rapidity of transformation I could not get my head around the business of recognizing them. Later I would try to record my impressions of the intermediate positions I had glimpsed and find it impossible.

“The consumption of the final morsel happened very quickly, and the word disappeared. As it did so it emitted a sound that is hard to describe. It might have been a very high-pitched or very fast declaration. It seemed to contain many sounds, though it was over in no more than an instant.

“If I could hear that sound again, it seems to me I would understand everything that is now obscure to me. But perhaps I should not strain, through an act of violence, to translate dead matter into sense. When I myself am dead matter, I will speak the language of things. Then at last I will understand what it is that the world has been trying to tell me, all my life.”