“The enemy must give me fight, or I will be in Nashville before tomorrow night.”

–John Bell Hood to Chaplain Charles T. Quintard, November 29, 1864 30

All the players were now in place. General John Bell Hood’s army was feeling its way north into Tennessee in three columns. To the west, Major General Benjamin Franklin Cheatham’s corps marched toward Waynesboro. He commanded three divisions under Major Generals Patrick Cleburne, John C. Brown and William Bate, with Cleburne’s division considered one of the Army of Tennessee’s best. In the center was Lieutenant General Steven D. Lee’s corps of three divisions led by Major Generals Ed “Allegheny” Johnson, Carter L. Stevenson and Henry D. Clayton, headed over backcountry roads to Henryville. On the right, on the road to Lawrenceburg, was the third corps led by Lieutenant General Alexander P. Stewart with divisions commanded by Major Generals Edward Walthall, Samuel French and William M. Loring.

On paper, the three infantry corps reported an “aggregate present” of just over forty thousand men, but the effective total (armed troops actually present for duty) was actually nearer twenty-eight thousand. In addition, Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest commanded three cavalry divisions, led by Brigadier Generals James R. Chalmers, Abraham Buford and William H. “Red” Jackson—about five thousand troopers. Chalmers was to the west while Buford and Jackson were on the Lawrenceburg road, sparring with Federal cavalry and screening the movements of the army. As he moved into Tennessee, Hood’s army’s effective strength was about thirty-three thousand men of all arms, plus another four thousand or so unarmed support troops.31

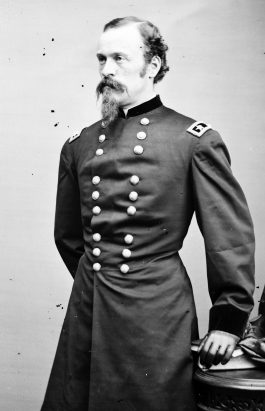

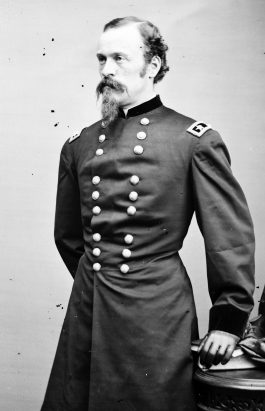

Major General James Harrison Wilson, commander of the Union cavalry during the Tennessee Campaign. Library of Congress.

The best of the roads were awful, with axle-deep mud in many spots, and the worst, the one assigned to S.D. Lee’s center column, abysmal, being a country lane barely able to carry local traffic let alone thousands of men, wagons and animals. The weather didn’t let up either. The cold wind, rain, sleet and occasional snow tormented the men, many of whom still lacked blankets, coats and footwear. General Cheatham had actually ordered his men without shoes to make them out of beef hides, turning the hair to the inside and stitching up the leather. They were said to be fine to walk in but didn’t smell too good after a few days.32 Still the men moved steadily on. Some of the Tennessee men were marching through familiar neighborhoods and were just glad to be back home.

The Federal army, whose job it was to watch the Confederates and delay, as best they could, any move they made to the north, had its infantry concentrated at Pulaski, Tennessee, which put them over fifteen miles east of the nearest Confederate column. The Federal 4th Corps, commanded by Major General David Sloane Stanley, had been the first on the scene. With three divisions commanded by Brigadier Generals Nathan Kimball, George D. Wagner and Thomas J. Wood, Stanley had been in place about two weeks. Just over a week ago, Major General John M. Schofield arrived with the 23rd Corps consisting of two divisions under Brigadier Generals Thomas H. Ruger and Jacob D. Cox. In addition, cavalry units under Brigadier Generals John Croxton and Edward Hatch were sparring with Forrest’s units east of the Lawrenceburg road and Colonel Horace Capron’s brigade was west of Mount Pleasant. Just as the Confederates began to move north, Major General James H. Wilson arrived to take over command of the scattered cavalry units. On November 13, Schofield assumed command of all forces, which his commander, General Thomas, estimated at twenty-five thousand troops of all arms.33

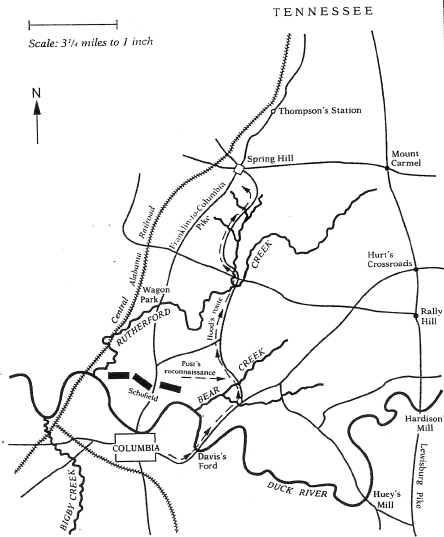

For three days, the Confederates marched north and the cavalry skirmished, with the Yankee riders being roughly handled by Forrest’s veterans. By the evening of the twenty-third, the Federal infantry had begun to fall back north from Pulaski to Columbia; Hatch and Croxton’s men were being pushed east from Lawrenceburg; and Capron’s cavalry had been driven north through Mount Pleasant. Early on the morning of the twenty-fourth, Capron was routed again and was soon in full retreat up the pike toward Columbia. Only the timely arrival of Schofield’s lead infantry division under Jacob Cox, who blocked the pike and turned back James Chalmers’s pursuing Confederate troopers, saved Capron’s men and kept Forrest from riding into Columbia, which was garrisoned by a single Federal brigade.34

Having lost the sprint up the pike to capture Columbia, Hood spent the next two days bringing up the rest of his force. He sent S.D. Lee with two of his divisions to confront the Yankees directly in Columbia and held the rest of his force out of sight behind a ridge south of town. On the evening of the twenty-seventh, two things happened. General Schofield notified Thomas in Nashville that he was falling back across to the north side of the Duck River, and General Hood held a meeting with his commanders at Beechlawn, the home of Mrs. Amos Warfield.

General Hood explained that he wanted to swing most of his army around the Federal left flank, and to do this, they had to find a suitable crossing on the Duck River and move the Federal cavalry, which was now guarding the fords, out of the way. This first phase of the operation would be General Forrest’s job. By daylight, Schofield had crossed the Duck River and taken up positions on a ridgeline on the north bank, while Confederate cavalrymen began to move across the same stream at four different places east of town. All day, Forrest pushed the Yankee riders back from the river and northeast along Lewisburg Pike. General Wilson, the Federal cavalry commander, was convinced that Forrest was headed up the pike to Franklin and ordered a concentration at Hurt’s Crossroads. Meanwhile, Confederate engineers had found a crossing point for the infantry at Davis Ford, and with the enemy cavalry gone, they spent most of the day preparing the approaches and getting pontoons in position.

Forrest had done his job well. He had moved most of the Federal cavalry north and east and out of the coming fight. The Duck River was now unguarded east of town, and Schofield’s cavalry—his eyes and ears—were out of position to observe the Confederates’ next move.35

Reports of the fighting east of Columbia and north of the river had been coming in to Schofield’s headquarters in the afternoon, and he had sent word to Thomas in Nashville asking for instructions. As the sun went down on that Monday, there was the real sense in the Federal camp that Hood and his Rebels were up to something.

John Schofield finally heard from his cavalry commander in the early hours of November 29, and it wasn’t good news. General Wilson confirmed Forrest’s movements of the twenty-eighth, gave some reports from prisoners and advised Schofield to withdraw to Spring Hill as soon as possible. Forrest was across the river, and Hood, with the infantry, would be close behind. Still waiting to hear from Thomas in Nashville with instructions, however, Schofield hesitated.36

In many ways, Schofield and Hood were opposites. Hood was often impulsive and sloppy in his planning, while Schofield was much more methodical and careful and usually tried to hedge his bets, which is what he did now. He decided to wait a little while with part of his force in front of Columbia until the situation cleared up somewhat—or until he heard from Thomas—but he began pulling in his outposts. He also got his baggage and supply trains—eight hundred wagons long—moving north, just in case. About daylight he sent General David Stanley and two of his three divisions marching north toward Spring Hill, escorting his wagons and reserve artillery. Not having any cavalry available, he then sent an infantry brigade marching east up the north bank of the Duck River to check on the reports of Confederate infantry crossing there.37 To add to the confusion, just after sunrise, Steven D. Lee’s men opened an artillery barrage from the south side of the river, designed to convince the Yankees that the whole Confederate army was still facing them. Before long, however, Schofield knew that this was not true.

Before daylight, John Bell Hood had his battered body in the saddle. His engineers had worked all night laying the pontoon bridge at Davis Ford, and now Hood rode across with General Frank Cheatham at the head of three divisions, beginning his “end run” of Schofield’s army. Following immediately would be General A.P. Stewart and his three divisions, and finally, a division borrowed from Lee’s corps—at least twenty thousand men in all. In front of them lay over fifteen miles of twisting country lanes before they reached their objective, the little village of Spring Hill on the Nashville Pike. Soon, this long column of gray would be seen by the infantry reconnaissance patrol, and by 11:00 a.m., Schofield knew for certain that he was being outflanked, but where were they going? Were they going to turn and hit him here at his present position or move farther north? He didn’t know.

In recent years, there have been questions raised as to Hood’s real motive for his flanking move. Some say that he intended from the start to trap the Union army and destroy it at Spring Hill, while others contend that he simply meant to outrun them to Nashville. To do either one, however, he had to gain possession of the pike at Spring Hill, and that was today’s objective.38

Major General James Wilson, with most of General Schofield’s cavalry, had been engaged with Nathan Bedford Forrest’s troopers all the previous day and had been pushed north and east up the Lewisburg Pike, going into camp at Hurt’s Crossroads after dark. In fact, Wilson had little hope of holding the place, so before sunup, he began withdrawing farther north to Mount Carmel. This was just what Forrest wanted, since he had a surprise in store for the Yankees that morning. Leaving just enough of a force to press the Federal cavalry up the pike, Forrest took another group around behind them, and just as Wilson reached Mount Carmel, he got hit from two sides. The Federal troopers were able to fortify the place and hold off the Confederates, but after a sharp little fight, the gray riders disappeared. Wilson was now convinced more than ever that Forrest was trying to get around him and make a dash up the pike for Franklin and Nashville, so he continued to fall back trying to prevent it. This was, in fact, exactly what Forrest had been working for since yesterday. Wilson had now taken himself and most of Schofield’s cavalry out of the real fight, which would begin soon, several miles to the west. Forrest left one brigade to keep encouraging the Bluecoats up the pike and then turned west with the rest of his men on the Mount Carmel Road toward Spring Hill, only five miles away.

Spring Hill, Tennessee, was a small village about halfway between Columbia and Franklin, on the main road and railroad south from Nashville, but it had already seen its share of the war. There had been a battle near there in March 1863, and then it became the headquarters of Confederate cavalry commander General Earl Van Dorn until he was killed in his own office by a jealous husband a few months later.

Approach to Spring Hill. Carter House Archives, Sword collection.

When November 29, 1864, dawned, Spring Hill was just an outpost on the pike manned by the 12th Tennessee Cavalry, a new Federal unit with no combat experience. Their job was to maintain pickets on the local roads and run a dispatch service between Franklin and Columbia, a distance of about twenty-two miles. This morning, however, the town began filling up. Dribs and drabs of different units began to come in from several directions.

By late morning, the head of the long wagon train from Columbia began to arrive, escorted by several companies of Illinois and Ohio infantry. Trotting up the pike alongside the wagon train also came elements of the 3rd Illinois and 11th Indiana cavalry who had been pulled back from picket duty on the Duck River fords west of Columbia. Finally, from the east came a wandering company of the 2nd Michigan Cavalry, who had been separated and cut off during the fighting with Forrest the day before along Lewisburg Pike. Somehow, they had managed to work themselves west during the night and rode into Spring Hill just happy to be alive. It was a grab bag of small detached units, many searching for their larger commands, but Lieutenant Colonel Charles C. Hoefling, in charge of the tiny garrison at Spring Hill, would very soon thank his lucky stars for every one of them.

About 11:00 a.m., just as the last of these units was trying to work its way through the traffic jam of wagons and teams in the town, word came to Lieutenant Colonel Hoefling from his pickets out on the Mount Carmel Road that a large force of Confederate cavalry was approaching. Hoefling frantically gathered up all the bits and pieces of the units in town and sent them east to defend as best they could. Nathan Bedford Forrest had arrived.

About two miles east of town, Forrest’s skirmishers began to encounter the Federal pickets but were able to move them back with relative ease, causing Forrest to think that the town might only be held with a small force. Hoping to “keep up the scare,” as was his motto, he formed up Frank Armstrong’s Mississippi Brigade and parts of two other units and ordered an attack up the road. As they chased the pickets up some high ground, however, they got a nasty surprise. Lieutenant Colonel Hoefling’s little ragtag army had moved quickly into a good position on the hill, and many of the Yankees latecomers were combat veterans with breechloaders or Colt revolving rifles. As the pickets ran into their lines, the Federals with their superior weapons opened fire and stung the pursuing Confederates badly, causing them to fall back and regroup.

One little setback, however, didn’t slow Forrest down in the least. He immediately sent another unit around to flank the Federal position, only to have them get a bloody nose as well. The wayward Company “M” 2nd Michigan Cavalry, which had escaped capture the day before, now arrived on the scene and pitched into the flanking Confederates with their seven-shot Spencer repeaters. The thrown-together defending force was giving a good account of itself, but it couldn’t last. Forrest had over four thousand troops, so the best the Northern soldiers could do was fall back slowly, hoping that the men back in town were using the time wisely. As it happened, they were.

By noontime, Spring Hill was alive with activity. General George Wagner had his division, which had been with the wagon train, double timing the last mile or so into town. Two brigades would be there within a few minutes—Emerson Opdycke’s to the north to protect the wagon park and John Q. Lane’s stretching the line east of town. These two units arrived just in time to drive off the Confederate skirmishers who were following the Mount Carmel defenders as they fell back into town. It had been a near thing. A few minutes later, and Forrest would have been among them for sure, but in the end, he lost the race to Spring Hill.

For the next few hours, all Forrest and his troopers could do was skirmish and probe the Federal position, which grew stronger with the addition of Wagner’s third brigade under Brigadier General Luther Bradley and most of the army’s reserve artillery. Bradley covered the southeast sector, which included Rally Hill Pike, the most likely avenue of approach for Hood’s infantry.

Forrest had done all he could. His men were exhausted, and since they had to leave their supply wagons back in Columbia, they were almost out of ammunition. After fighting for the last day and a half, most units were down to just three or four rounds per man. All he could do was hold on and wait for the infantry.