“We will make the fight.” 51

–John Bell Hood about 2:00 p.m., November 30, 1864

In contrast to his plan for a sweeping, complicated maneuver at Spring Hill, Hood’s plan at Franklin was elegant in its brutal simplicity. He would simply hit them head-on with everything he had. At the beginning of the attack, he had available on the field two full infantry corps, each composed of three divisions—eighteen brigades made up of over 120 regiments: nearly 18,000 men. In addition, he had Forrest’s cavalry on each flank, something above 4,000 troopers. Finally, General Ed Johnson’s 2,700-man division of S.D. Lee’s corps would arrive after the attack was underway and be sent in after dark. During the next five hours, John Bell Hood would commit to battle, somewhere on the field, almost 25,000 men.

After the war, many would criticize Hood for his decision to send his army to attack the Yankees head-on at Franklin. As the commander on the field, the blame was rightly his, as would have been the glory if he had succeeded, and in retrospect his decision can be seen as tragically flawed, but not for some of the reasons others have given. It’s highly unlikely, for instance, that Hood was unbalanced enough to send his men forward just to “teach them a lesson,” and there is no evidence that he was acting under the influence of such painkillers as were available. By far the most reasonable explanation seems to be that Hood simply deceived himself as to what could be accomplished. His reasoning that he must strike at the Federal army before they reached the safety of the fortifications at Nashville was quite correct. To some extent, Hood’s attack was an act of desperation. Something had to be done at Franklin before sundown or he would lose his last chance at this Federal army. In fact, General Schofield had already issued orders to begin withdrawing the Federal infantry from the entrenchments and passing them over the river as soon as it was dark if no attack came.

What probably sent Hood’s men forward was the same sort of self-delusion that caused Robert E. Lee to send almost twelve thousand men across the field on the third day at Gettysburg, against the pleas of their corps commander, General James Longstreet, who, like Forrest, begged for the chance to try a flanking movement instead. Hood was now about to send over twenty thousand men on a similar mission. Like Lee, Hood had convinced himself, against all advice, that the Federal line would break if hit hard enough in the center. Both Hood and Lee committed cardinal sins of command: they made unreasonable demands on their own men, and they underestimated the strength and courage of their opponent. The price for their clouded vision was, of course, borne by the men on the field. For Lee’s part, he immediately realized his mistake and rode among the survivors of Pickett’s Charge telling them that it was all his fault. Both circumstances and Hood’s personality prevented him from being able to do the same.52

Hood’s plan would send A.P. Stewart’s three divisions forward on the eastern half of the field following the Lewisburg Pike and the Nashville & Decatur Railroad tracks. Covering the right flank next to the Harpeth River would be dismounted elements of Forrest’s cavalry. Next would come the division under Major General William Wing Loring. On Loring’s left was the division of Major General Edward Cary Walthall, and on Stewart’s left flank was the division of Major General Samuel Gibbs French.

Frank Cheatham’s corps would cover the western half, with Major General William Bate’s division’s left flank on the Carter’s Creek Pike and dismounted cavalry covering his left. Straight up the middle would come the divisions of Major General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne and Major General John Calvin Brown, with Cleburne on the right of the Columbia Pike, connecting with French’s division, and Brown on the left, connecting with Bate.

Some have suggested that Hood put Cleburne and Brown in the center to punish these two divisions for their part in the failed attacks at Spring Hill, but there is no evidence of that. The real reason is probably the most obvious—in spite of what may or may not have happened the day before, these two units were still Hood’s best. Between them, Cleburne and Brown could field almost seven thousand men. The point where the pike passed through the Federal works would be the critical spot, and if Hood was to have any hope of breaking the enemy line, his heaviest blow would need to fall there. The other obvious reason they drew the assignment was simply because they were there. Cleburne and Brown’s men were already on both sides of the pike. To move them anywhere else would have taken time that Hood didn’t have.

Franklin, Tennessee, November 30, 1864. Library of Congress.

By 3:30 p.m., Confederate units could be seen from Franklin, falling into line in the open fields to the south. Regimental and division flags were flying and bands were playing. From almost two miles away, it looked like a grand military review to the Federal troops manning the entrenchments on the south edge of town. Even so, everybody realized that this was no parade, so they watched with keen professional interest.

Major General John Schofield and Brigadier General Jacob Cox rode into the outskirts of Franklin, Tennessee, about 4:30 a.m. at the head of Cox’s division, the vanguard of the Federal army—almost two hours before sunrise. Cox and his men had covered twenty-two miles in ten hours. Cox stopped at the first house he came to, woke up Fountain Branch Carter and his family and established his division headquarters in their front parlor. General Schofield rode on into town in search of his engineering officer, Captain Twinning, whom he had sent on ahead. Above all, Schofield hoped to find railroad cars with pontoons on them. The county bridge over the Harpeth River was known to be out, so Schofield had twice wired General Thomas requesting that he send pontoons down to Franklin to be available for the engineers. Schofield had almost eight hundred wagons to move across the river, the last natural barrier before Nashville, and without pontoons he could well be stuck south of the river all day while Hood and his army caught up. The last thing he wanted was to have to fight with the river at his back.

The soldiers were falling out on either side of the road, filling up Mr. Carter’s yard, starting fires and cooking coffee. Jacob Cox and his staff were sprawled all over Mr. Carter’s rug in the parlor, trying to catch a few winks of sleep, when General Schofield reappeared and woke him. He had just returned from the river. Over thirty years later, Cox wrote of their conversation:

In all my intimate acquaintance with him, I never saw him so manifestly disturbed by the situation he was in…that morning. He spoke with a deep earnestness of feeling he rarely showed. “General,” he said, “the pontoons are not here, the county bridge is gone, and the ford is hardly passable. You must take command of the 23rd Corps and put it in position here to hold Hood back at all hazards till we can get our trains over and fight with the river in front of us. With Twinning’s help I shall see what can be done to improve the means of crossing, for everything depends on it.”53

So began what was probably Jacob Cox’s finest day in a Federal army uniform. General Schofield’s engineers would rebuild the washed-out wagon bridge, plank over the railroad bridge and finally begin crossing the wagons over the river that afternoon, but by then, all Jacob Cox’s attention would be focused in the opposite direction.

When the war began, Jacob Dolson Cox was thirty-three years old, married, the father of six children and in poor health. Because of political connections, however, he was able to obtain a commission as a brigadier general in the Ohio militia, but unlike some political appointees, Cox turned out to be a solid, dependable soldier. After the war, he would go on to several careers as a public servant, educator, lawyer and writer, but that was all in the future. Today, his job was to defend John Schofield’s bridgehead over the Harpeth River.

Around the south edge of Franklin, there were some old entrenchments, dug by the Federal forces a year or so ago, and Cox decided to use them as the basis for his defense. As the troops arrived from Spring Hill, Cox turned them out into this old line and ordered them to improve it as best they could. Cox began with his own division. They were already on hand, having marched in with him, and they were the troops he knew best.

Starting on the east, with their left flank on the Harpeth River, was Cox’s third brigade, Indiana men commanded today by Colonel Israel N. Stiles.54 They stretched from the riverbank and railroad bed on their left to the Lewisburg Pike, covering a front of about 250 yards. Next came the second brigade under Colonel Joseph S. Casement, running from the Lewisburg Pike to a point just in front of Mr. Carter’s cotton gin, about 400 yards. Finally, Brigadier General James W. Reilly’s first brigade covered the critical area from the cotton gin to the Columbia Pike with two regiments on the line and three more in reserve—a front of about 160 yards. Because of Cox’s temporary promotion to corps command, Reilly, as senior brigade commander, took over command of the division as well. Incorporated in this line were eight artillery pieces with twelve more a few hundred yards in the rear.

As Thomas Ruger’s division arrived, short one brigade, they were set to work on the fortifications west of the Columbia Pike. Colonel Silas A. Strickland’s brigade went in with the 50th Ohio Regiment on the pike linking up with the 72nd Illinois to the west. Sixty-five yards in their rear, running from the pike, behind Mr. Carter’s farm office and smokehouse, and down the western slope of Carter Hill, two new regiments began digging a second fallback line. In the two days that the 44th Missouri and the 183rd Ohio had been with Schofield’s army, all they had done was march, and they dragged into Franklin having covered twenty-two miles since sundown the day before. Because they were untested and late in arriving, they were put along this second line, the 44th beginning just east of the pike and the 183rd extending the line to the west. Completing the front line from Strickland’s brigade to the Carter’s Creek Pike was Colonel Orlando H. Moore’s brigade, the line west of Columbia Pike being about the same length as the eastern part. This section of the line was supported by ten artillery pieces firing from Carter Hill and four more near the Carter’s Creek Pike.

The balance of the Union infantry—the 4th Corps under Major General David S. Stanley—was divided into three sections. One division under Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood was sent across the river via the ford and the railroad bridge to act as a covering force, able to protect the bridges and guard the wagons after they had crossed. Brigadier General Nathan Kimball’s division was sent to extend the front line west of Carter’s Creek Pike on to the Harpeth River northwest of town, throwing up barricades using whatever material was at hand, while Brigadier General George Wagner’s division acted as the army’s rear guard. Finally, General Wilson and the cavalry had reestablished contact and were on both sides of the river east of town, ready to counter any flanking move by Forrest. Of these troops, almost all of the heavy fighting would be done by the two divisions of the 23rd Corps in the mainline and George Wagner’s division from the 4th Corps, almost fifteen thousand men in all.55

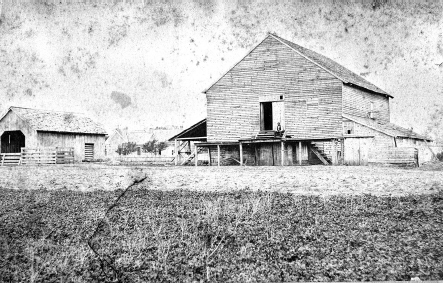

The Carter cotton gin and press house as seen from Columbia Pike, circa 1880. Cleburne’s division attacked up the road in the foreground. Major General Patrick Cleburne was killed between the fence and the gin house. U.S. Army Military History Institute.

Few Civil War battlefields offered such an unrestricted view of the ground in front of the defenders as Franklin. Open fields with only a few groves of trees stretched out in the Union army’s front for two miles, and it was over this ground that any attacker must pass. Having troops in the open for so long was an artilleryman’s dream and would shortly become the Confederates’ nightmare. To make matters worse, while the field started out almost two miles wide, as an attacker got closer to the Federal lines, the Harpeth River began to pinch in on the east so that units on that flank were obliged to shift to their left, crowding others off their original line of advance and mixing regiments and brigades together. It was like marching down into a funnel. When they finally reached the Federal entrenchments, Hood’s entire attacking force would be compressed onto a front barely 1,600 yards wide. So many men packed into such a small space, and all fighting for their lives, would shortly produce a level of horror, bloodshed, violence, brutality and hand-to-hand combat beyond the experience of even the most hardened veterans on either side. One Federal officer, defending the line about two hundred yards west of the Columbia Pike, would later simply say, “I thought I knew what fighting was.”56

Many modern innovations made their appearance in the Civil War, but some things about military engineering hadn’t changed in centuries. The Federal entrenchments were classic in design—the best protection for the defender and the most obstruction for the attacker. Julius Caesar had built very similar defensive works two thousand years before in Gaul. For the most part, they consisted of two ditches dug parallel and several feet apart. The dirt from the ditches was thrown to the center. When finished, you had a dirt berm maybe five feet high with a ditch three feet deep or so on the outside and a slightly more shallow one on the inside. This made an eight-foot obstacle for an attacker and a secure shelter for the defender. Trees were cut down to provide timber to put along the top, and underneath these head logs firing slits were dug out. In front of the works, more obstructions were built out of whatever was available. On the eastern end of the line, a long hedge of Osage orange trees (also called Bois D’Arc) ran less than fifty yards in front of Stiles’s brigade. These trees, which contained long thorns on their branches, were cut off about four feet above the ground and the tops used to extend the line of thorn bushes to the right, in front of Casement’s men. Any attacker would have to stop within easy rifle shot and, in full view of the men in the trenches, work their way through a thorny thicket before being able to storm the works.57

Carter cotton gin circa, 1880. Some of the fiercest fighting of the battle took place around this building. It was torn down a few years after this picture was taken. Carter House Archives.

On the west side of Columbia Pike, a grove of locust trees served much the same purpose—anything to break up the momentum of an attacking force and make them an easier target. Only in the center, from in front of Mr. Carter’s cotton gin west to the locust grove, was the ground relatively unobstructed all the way to the mainline of entrenchments.58

Shortly after noon, the work on the Federal lines was largely finished, and the men began to relax, cook rations, smoke or sleep. At Fountain Branch Carter’s house, two families of neighbors had come with their children, knowing that Carter had a basement for shelter in case of trouble. One of the families lived on the other side of Columbia Pike just north toward town. German immigrants Johann Albert Lotz and his wife Margaretha had bought the house lot from Mr. Carter, and Johann, a master carpenter who did intricate woodwork and built fine pianos, had done most of the work on their house himself. Feeling that Mr. Carter’s brick house would be a better shelter than their frame one, however, Johann and Margaretha had brought their three children, Paul, Matilda and Augustus, across the street to weather the storm, if it came. This proved to be a good decision because before long their house would suffer substantial damage from small arms and artillery fire, some of which can still be seen. The Lotz House would also serve, along with the Carter House, as a hospital after the battle. Both houses still stand on Columbia Pike today.

The Lotz House. Home of Johann Albert Lotz, a German immigrant and master carpenter. Lotz and his family lived across the street from Fountain Branch Carter and took refuge, along with other civilians, in Carter’s basement during the battle. Lotz House.

At least three members of the black families who worked for Mr. Carter were there also. A Carter family story says that all the Carter slaves were freed in 1859, but no documentation exists to support that. The 1860 census shows Fountain Branch Carter as owning twenty-eight slaves. Whatever their status, several black families still worked for Carter and lived on his property. He was farming almost three hundred acres of land as well as operating his cotton gin, so dependable labor was essential. By 3:30 p.m., at least twenty-seven civilians were inside the Carter House, probably half of them children.59