XI.

North America since 1920

AMERICAN VOICES

Ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution on August 20, 1920, marked the culmination of decades of work by women activists. However, with the right to vote secured, the intensity of collective activity among American women diminished. According to historian Sara M. Evans, “The twenties formed an era when changes long under way emerged into an urban mass culture emphasizing pleasure, consumption, sexuality, and individualism.”1 These traits were present in the popular music, e.g., jazz and the Charleston, which emerged from black culture and spread into the dominant white culture. Perhaps even the plurality of styles within American music was an outgrowth of a social context focused on individuality and diversity within American life. Consider, for example, the various piano styles represented among the following performers and composers: Lovie Austin's accompaniments for blues singers, Lil Hardin Armstrong's performances and recordings with many leading jazz artists, From the New Hampshire Woods by Marion Bauer, and the piano preludes of Ruth Crawford Seeger.

Marion Bauer and Mary Howe

The musical language of Marion Bauer (1882–1955) and Mary Howe (1882–1964) remained strongly rooted in the Western European harmonic tradition. Rather than followers of the Second New England School, which favored abstract instrumental forms, Bauer and Howe are descendants of Edward MacDowell's emphasis on coloristic harmony, programmatic titles, and narrative, through-composed forms. Both women traveled in Europe during the early twentieth century, and Bauer was among the first American composers to study with Nadia Boulanger. In exchange for harmony lessons in 1906, Bauer provided English lessons to both Nadia and Lili Boulanger as well as to the daughter of Raoul Pugno, Bauer's violin teacher.

Bauer's From the New Hampshire Woods (1921) is firmly grounded in periodic rhythm, tertian harmony, and an integrated melodic-harmonic unit, yet it is colored with tints of impressionism. Written three years later, Turbulence for piano (1924) moves further away from functional tonality with more complex harmonies. Rhythmic energy, more than harmonic seduction, propels this work. Giving it a feminist reading, Ellie Hisama analyzes Bauer's Toccata from the Four Piano Pieces (1930) in terms of gender, sexuality, and shifting power relationships, based on the changing physical relationship of the pianist's hands.2 Characterized in the 1920s as the work of a left-wing modernist, by the 1940s Bauer's music was viewed as conservative, yet well-crafted.

Bauer was well recognized during her lifetime with publications and many performances, including those by such prominent soloists as Ernestine Schumann-Heink (alto) and Maud Powell (violin), as well as by the New York Philharmonic under Leopold Stokowski for a 1947 performance of Sun Splendor (1926; orchestrated 1944?). This was the only work by a woman the Philharmonic had performed for a quarter of a century. Mary Howe's orchestral tone poem Spring Pastoral (1937) was originally a setting of a poem by Elinor Wylie for women's chorus. In the orchestral version, lush string writing supports the soloistic treatment of French horn and woodwinds. Howe also composed character pieces for piano as well as other orchestral tone poems, including Dirge (1931), Stars (1927?), Sand (1928?), and Potomac (1940).3

Both Howe and Bauer produced many of their compositions at the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire. Howe spent summers there almost every year from 1927 onward. Bauer, who visited twelve times between 1919 and 1944, expressed her gratitude to Mrs. Edward MacDowell for founding “a haven where many other composers, writers, and painters have shared with me the extraordinary opportunity and privilege of doing creative work in peaceful, stimulating, and beautiful surroundings.”4 Along with a supportive atmosphere, the Colony also offered Bauer an opportunity to meet other important women composers such as Amy Beach, Ruth Crawford, and Miriam Gideon. For Howe, Bauer, and others, the MacDowell Colony was a very stimulating “room of one's own”—a necessary component for creative activity by women, according to Virginia Woolf.

Howe and Bauer also made substantial contributions to American musical life beyond composition. Howe, one of the founders of the Association of American Women Composers, was active in many artistic and philanthropic organizations. Bauer, a champion of American music, was active in many musical organizations and was frequently the only woman in a leadership position in groups that included America's most prominent composers. She was editor of the Musical Leader, author of many articles and five published books, and, for twenty-five years, professor of music history and composition at New York University.

Florence Price

In a self-conscious effort to find an American voice and to establish artistic independence from the Central European tradition, some composers in the 1920s and beyond cultivated musical nationalism, incorporating elements from vernacular or ethnic music. Florence Price (1887–1953)5 had ties with the Harlem Renaissance, which sought “the elevation of the Negro folk idiom—that is, spirituals, blues, and characteristic dance music—to symphonic form. This elevation could be accomplished through the fusion of elements from the neo-romantic nationalist movement in the United States with elements from their own Afro-American cultural heritage.”6 Price was the first black woman to gain recognition as a major composer. Her Symphony in E Minor (1931) was among the earliest by an African American to be performed by a major orchestra, receiving its premiere at Chicago's World's Fair Century of Progress Exhibition concert in the Auditorium Theatre (not at Orchestra Hall). While this symphony does not quote preexisting tunes, it promotes racial pride and awareness. It uses various Afro-American characteristics: incorporating a pentatonic scale, call-and-response, syncopated rhythm, altered tones (or “blue notes”), and timbral stratification, as well as the more obvious inclusion of a juba dance (in the third movement) and African drums (especially prominent in the second movement). Similar characteristics are found in many of Price's art songs, piano pieces, organ music, and the Piano Concerto in One Movement (1933–1934).

G. Wiley Smith

G. Wiley Smith (b. 1946), an active flutist and teacher as well as a composer, grew up in Sapulpa, Oklahoma, and received her bachelor's and master's degrees from the University of Central Oklahoma in Edmond, Oklahoma, where she is currently professor of flute. A member of the Muskogee Creek Nation, Smith is also active in the Indian Education Program in the Edmond Public Schools. She has performed her music at the Indian Education Exposition in Norman, the Red Earth Artist Presentation, and the Seminole Nation Student Honor Reception. Smith's music preserves the sounds of traditional Native American flute playing while adding contemporary influences from her training as a Western flutist. The style of the opening and closing sections of Whisper on the Land for Western flute and piano is especially reminiscent of Native American flute playing. Smith says about this work, written to honor her father:

The piece reflects Native American music and is particularly reminiscent of the native flute. There gradually begins a battle between the cultures as more and more contemporary Western influences are introduced.

This conflict, which many generations of Native Americans have experienced, continues today. I personally have lived with many conflicting values and traditions. Although the Indian culture has all but been eliminated, it still remains a “whisper,” as heard in the closing measures.7

Smith's composition Legende, like Whisper on the Land, shows respect for the land as an important cultural value for her people, the Creek Nation. Smith offers the following description of Legende, written for alto flute (or flute) solo:

Whether passing information by spoken words, through paintings, or through music, Indians are natural storytellers. The story of Legende begins near water where an Indian flutist begins to describe the nearby scenery. The teller continues, reflecting on cultural heritage. One can imagine the wealth of proud experience from which the story unravels and fades in quiet melancholy.8

Depicting the American Scene

Works by white composers also included the experiences and music of African Americans. Mary Howe's Chain Gang Song (1925) for chorus and orchestra (originally for piano) was her first major composition to be performed publicly. It incorporates three tunes sung by a crew of black prisoners in the mountains of western North Carolina. In her autobiography, Jottings, Howe describes the experience that prompted this composition:

[I was] rounding a bend on horseback…and coming on a gang of twenty or so black convicts in striped clothes…iron ball and chain on many feet, and they sang while they drilled the hole for the dynamite charge. One man held and aimed the iron drill, and two more slugged at it with heavy shoulder weight iron hammers, rhythmically, so the three could know inevitably when the hammer blows would fall.9

White composers from other regions of the United States also participated in the American music movement through conscious inclusion of American themes in musical materials. Two Texans, Julia Smith (1911–1989) and Radie Britain (1899–1994), incorporated musical idioms typical of the rural West and Southwest—hoedowns, songs of the rodeo and range, Spanish-American elements, and desert themes. Smith's American Dance Suite (1936, rev. 1963), an orchestral work, sets folk tunes; it was later arranged for two pianos (1957, rev. 1966).10 Cynthia Parker (premiered 1939), an opera based on the fascinating and tragic story of a young white girl lovingly raised by Comanches and forcibly “repatriated” by whites, quotes Native American melodies. The descriptive titles of several of Britain's works for orchestra bring to life her native Texas: for example, Drouth (1939, also for piano); Red Clay (1946, later versions for piano and a ballet), which employs Indian rhythms; Cactus Rhapsody (1953, also for piano; 1965 arr. for two pianos; 1977 arr. for trio); and Cowboy Rhapsody (1956). Spanish-American rhythms are prominent in Rhumbando (1975) for wind ensemble.

Mary Carr Moore (1873–1957), active as an organizer of several societies to promote American music, employed materials from the Northwest and California, areas in which she spent most of her adult life. Two of her operas, Narcissa (1909–1911) and The Flaming Arrow (1919–1920), make extensive use of American themes and Native American materials. Moore and her mother, who prepared these librettos, worked hard to understand Native Americans—their music, their culture, and the shameful ways in which white Americans had treated them. Narcissa, based on the 1847 massacre of missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman in the Pacific Northwest, is original in presenting the drama through a woman's eyes. Both dramatically and musically, Narcissa's character is the most fully and deeply drawn within the opera. In Moore's opera David Rizzio (1927–1928), another strong woman is the focus: Mary, Queen of Scots.

AMERICAN EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC

Ruth Crawford Seeger

Ruth Crawford Seeger (1901–1953) took a different yet thoroughly American path: on the surface she separated her compositional activity from her work with folk materials. Yet as Judith Tick demonstrates, Crawford Seeger wove together the strands of her multifaceted careers with a process of “cultural mediation.”11

FIGURE 11.1. Ruth Crawford Seeger sings folk songs with children at a cooperative nursery school in Silver Spring, Maryland, ca. 1941–1942. Photo courtesy of Michael Seeger and the Estate of Ruth Crawford Seeger.

Because she [Crawford Seeger] remained first and foremost a composer, no matter what she did, all of her various activities as transcriber, editor, and arranger of folk materials reflected that sensibility. I began to see how she understood tradition through a modernist perspective, finding affinities that linked the very old with the very new. An ideology of opposition pervaded her work. Just as modernism flouted conventional practice, so did tradition. Just as modernism rejected Romantic excess, so did tradition. Decoding the ways opposition as a value informed her musical choices integrated the two parts of her musical identity.12

The ambiguities and tensions between the “stratosphere” of classical music and the “solid well-traveled highway” of folk song—as Crawford described them in a 1948 letter—were real but not insurmountable for this experimental composer, wife, mother of four children, transcriber and arranger of folk music, piano teacher, and music educator. During the late 1920s and early 1930s Crawford was one of the most innovative, ultramodern American composers, along with Henry Cowell, Edgard Varèse, and Carl Ruggles. Then, from the mid-1930s she concentrated on folk music, setting high standards of transcription with her work from field recordings. She worked with Alan and John Lomax, transcribing American folk songs found at the Library of Congress (Our Singing Country, 1941); created piano arrangements and accompaniments for folk songs (Folk Song U.S.A., 1947, with the Lomaxes and Charles Seeger); and compiled and edited materials for children (American Folk Songs for Children, 1948; Animal Folk Songs for Children, 1950; American Folk Songs for Christmas, 1953). In one composition Crawford did utilize folk melodies: Rissolty, Rossolty (1939) was written for a radio series on folk music, and it was her only concert piece composed between the birth of her first child in 1933 and her final composition, Suite for Wind Quintet (1952). Carrying on her legacy, two of Crawford's children, Michael and Peggy, became professional folk singers.13

Crawford's compositions from the 1920s show influences from Scriabin's music, which she had studied with Djane Lavoie-Herz, her piano teacher and a Scriabin disciple. In nine preludes for piano, written between 1924 and 1928 (see HAMW, pp. 271–75 for Prelude No. 2), Crawford's use of melodic cells, dissonance, and irregular phrasing forecast her later stylistic directions. Suite for Five Wind Instruments and Piano (1927, revised 1929), an intense and dramatic work, is rhapsodic, presenting divergent musical ideas and a wide emotional spectrum. Crawford's demanding piano writing suggests her technical skill as a pianist and demonstrates her understanding of the piano's expressive capabilities.

Crawford's eight years of study in Chicago offered many opportunities for an emerging composer: participation in the new music circle that gathered at Madame Herz's salons, acquaintanceship with Carl Sandburg, and, perhaps of greatest impact, her professional relationship with Henry Cowell. Cowell published several of Crawford's works in his influential series, New Music. He is also credited with arranging her move to New York in 1929 and her year of study with Charles Seeger, whom she later married.

From 1930 Crawford's compositions realized in sound the ideas and theories that Charles Seeger articulated primarily with words. He called for a procedure that would reverse or negate tonal organization to allow greater importance for nonpitch parameters. Crawford first cultivated this approach, called dissonant counterpoint, in four Diaphonic Suites for one and two instruments and in Piano Study in Mixed Accents, all composed in 1930. Employing Seeger's principles, Crawford created independent musical lines, described by Seeger as “‘sounding apart’ rather than ‘sounding together’—diaphony rather than symphony.”14 Her innovative structures employed an economy of melodic material to create organic wholes; elevated the importance of rhythm, dynamics, accent, and timbre; and enacted a role reversal between consonance and dissonance. In parameters other than pitch, Crawford and Seeger defined dissonance (or “dissonating”) as the avoidance of patterns established through repetition and predictability.

Crawford used a serial rotation with a ten-note set in the fourth movement of String Quartet 1931 (see HAMW, pp. 285–90 for the third and fourth movements), coupled with a layered pattern of long-range dynamics and a palindrome structure. Dynamics are also the primary organizing element in the third movement, which Crawford described as a “heterophony of dynamics.”15 String Quartet 1931, which she considered her most representative work, was composed during the productive year she spent in Europe on a Guggenheim Fellowship, the first ever awarded to a woman.

Three Songs (1930–1932), for contralto, oboe, piano, and percussion (see HAMW, pp. 276–84 for “Rat Riddles”), is one of Crawford's most innovative works and employs experimental techniques that only decades later became widely used. In addition to her continued use of dissonant counterpoint and palindromic structures that govern the rhythm and dynamics, Crawford's compositional techniques include vocal performance in “somewhat (though not too much) of the ‘sprechstimme’ mode of execution”16 for the declamatory vocal line; tone clusters in the piano part; and optional instrumental ostinatos spatially separated from the primary performers. The level of independence among the four concertanti performers is remarkable, yet Crawford created an expressive musical whole consistent with the poems by Carl Sandburg that she set.17

Vivian Fine

Vivian Fine (1913–2000) continued in the experimental vein of her first theory teacher, Ruth Crawford. Fine studied with Crawford for four years, beginning at age twelve, and began composing at thirteen. Four Pieces for Two Flutes (1930) and Four Songs for voice and string quartet (1933) show an affinity with compositions by Crawford. In each of these early works Fine skillfully employs dissonant counterpoint. The third song, “She Weeps over Rahoon,” involves carefully planned serialized pitch sets that are not related to twelve-tone technique. According to Steven Gilbert, this song “shows a remarkable degree of pitch and timbral control—this in addition to its being a very moving piece.”18

Fine, an accomplished concert pianist, received a scholarship to study piano at Chicago Musical College with Djane Lavoie-Herz, one of Crawford's teachers, when she was only five years old. In 1931 she moved to New York to begin her career. In addition to premiering much new music, she earned her living as a dance accompanist. Her experience and success in this area led to collaborations with many leading modern dancer-choreographers, including Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, Hanya Holm, and Martha Graham. Between 1937 and 1944, when Fine was most actively composing for dance, her writing moderated to display a more diatonic style, as in The Race of Life (1937), a humorous and popular ballet score, and Concertante for piano and orchestra (1944).19 Fine identified this move toward tonal writing as an influence from her study with Roger Sessions, as well as a partial response to changing social conditions and a desire to communicate with listeners. Subsequent scores returned to atonality but with less sharp dissonances and an expanded expressive range. In the fourth movement of a 1960 ballet score, Alcestis (see HAMW, pp. 347–54), a prominent melodic motive rises in a succession of perfect fourths. Here an intervallic consistency and a rhythmic motive (a fanfare-like triplet) replace the hierarchical structure of tonality in providing unity to the composition. After the Tradition (1988), commissioned and premiered by the Bay Area Women's Philharmonic in celebration of Fine's seventy-fifth birthday, honors her Jewish origins, although the composer calls this a nonreligious work. The first movement is a Kaddish in memory of cellist George Finkel; the second movement takes its title (“My Heart's in the East and I at the End of the West”) from Yehuda Ha-Levi, a twelfth-century Spanish poet; and the final movement exhibits much vitality.

Several of Fine's compositions highlight feminist issues: for example, Meeting for Equal Rights 1866 (1976) and the chamber opera The Women in the Garden (1977). Meeting, for chorus, soloists, narrator, and orchestra, sets excerpts from nineteenth-century debates on women's suffrage. Although the work is highly complex (it requires three conductors), it still received favorable audience response. One reviewer described it as

a stirring and timely piece devoted to the unhappily still struggling cause of Equal Rights. Taking a feminist viewpoint that is full of righteous rage—which is understandable—and compassion—which is more important—Meeting for Equal Rights 1866…augments and dramatizes the conflicts and hopes of countless generations.20

Fine's libretto for The Women in the Garden brings together on stage Emily Dickinson, Isadora Duncan, Gertrude Stein, and Virginia Woolf (quoting from their writings) to create an evocative drama through their interaction.

After her retirement from Bennington College in 1987, Fine remained an active composer and generally wrote on commission. The following works suggest the variety of mediums for which she composed and exemplify the importance of lush string sound in Fine's compositions: Asphodel (1988) for soprano and chamber ensemble; Madrigali Spirituali (1989) for trumpet and string quartet (revised for string orchestra in 1990); Portal for violin and piano; Songs and Arias for French horn, violin, and cello; Hymns (premiered in 1992 for two pianos, cello, and French horn); and the chamber opera Memoirs of Uliana Rooney (1992–1994). Fashioned as a newsreel and including film sequences, Memoirs traces the long life of a woman composer who changes husbands several times as her musical style changes. In this chamber opera, which quotes extensively from her own earlier scores, Fine brings humor and satire to a feminist work.

SERIAL MUSIC

Many American men composers who reached prominence before World War II produced at least some serial compositions during the postwar years (e.g., Roger Sessions, Arthur Berger, and Aaron Copland), and many men composers of the mid-1950s and 1960s established their reputations using serial procedures (e.g., Milton Babbitt, Charles Wuorinen). In composer Jacob Druckman's assessment, “not being a serialist on the East Coast of the United States in the sixties was like not being a Catholic in Rome in the thirteenth century. It was the respectable thing to do, at least once.”21 However, as the twentieth century waned, many composers who began as serialists abandoned this process, and few young composers now take up this approach.

Louise Talma

Louise Talma (1906–1996) was among the composers who shifted to the path of twelve-tone writing.22 Talma, whose early compositions were neoclassical and tonal, first adopted twelve-tone serialism in Six Etudes (1953–1954). In a general way, she perhaps took her cue from Igor Stravinsky's gradual incorporation of twelve-tone procedures after the death of Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951). As a long-time student of Nadia Boulanger and as the first American to teach at Boulanger's Fontainebleau School in France (1936–1939), Talma was strongly influenced by Stravinsky's music. Like Stravinsky's twelve-tone works, Talma's music retains tonal qualities, and serialism is absorbed as an additional unifying factor. Further, Talma indicates she was influenced by Irving Fine's handling of twelve-tone materials in his String Quartet, composed in 1952, the same year that Stravinsky made his first move toward serialism in Cantata. Stylistically, music by Talma and Stravinsky share other common elements: melodies created from short motives, establishment of tonal centers by assertion, nonfunctional harmony, ostinatos, and shifting accents.

Initially, Talma's handling of the row was quite strict. After The Alcestiad (1955–1958), an opera written in collaboration with Thornton Wilder, her approach to twelve-tone ordering procedures became increasingly flexible, and her music often exhibited focus through an emphasis on subsets, intersecting rows, and combinatoriality. She utilized this process in various mediums: the choral work La Corona (1954–1955; see HAMW, pp. 321–32), The Alcestiad, and Textures (1977) for piano. Typical of the writing in her late style, she based Seven Episodes for flute, viola, and piano (1987) on a twelve-tone row, yet also employed traditional tonal relationships. In an analysis of The Tolling Bell (a cantata for baritone and orchestra, 1967–1969) Elaine Barkin concluded that:

Although the work may indeed be “freely serial” [Talma's description], it is not casual, not “indeterminate”; very carefully determined junctures are articulated, critical constraints have been imposed upon all dimensions of the work at “initiating moments” and “points of arrival,” the text-music associations are quite clear—neither overstated nor concealed.23

The text of Have You Heard? Do You Know? (1974–1980), like the libretto for The Alcestiad, offers ample opportunity to critique gender stereotypes and to raise larger feminist issues. During its seven scenes, we meet Della and Fred (a white, middle-class, suburban couple) and their neighbor Mildred. Analogous musical treatment for Fred's concern about the ups and downs of the stock market and Della's similarly moving hemlines gives parity to traditional male and female experiences. Their desire for a “quiet place” is also handled nonhierarchically, with closely related music. However, the work as a whole reinforces gender stereotypes, seems uncritical of the emptiness of the characters' conversations, and glorifies the desire for material things. Accompanied by a mixed chamber ensemble, Have You Heard? returns stylistically to neoclassicism with melodic recurrence, tonal referents, and ostinatos reminiscent of Stravinsky.

Joan Tower

Before 1974, the music of Joan Tower (b. 1938) employed various serial procedures. Prelude for Five Players (1970) opens with twelve pitch classes, subsequently handled as an unordered aggregate. According to Tower, Prelude “is divided into six sections which are differentiated by changes in tempo, texture, register and dynamics which, for the most part, are associated with various hierarchizations of the twelve-tone set structure.”24 During the early 1970s Tower gradually moved away from serial procedures: Hexachords for flute (1972) is based on a six-tone, unordered chromatic series, and Breakfast Rhythms I and II for clarinet and five instruments (1974–1975) complete the shift. Many of the works that follow are more lyrical and accessible, carrying image-related titles to “open a tiny window into the piece”25 for audiences. For example, Amazon I (1977) reflects on the almost constant flow and motion of the music and the Brazilian river; Wings (1981) draws on the flight patterns of a large bird, paralleled in the hovering and swooping lines of the solo clarinet; and Night Fields (1994) has a title selected to provide a setting consistent with some of the moods of this string quartet. Tower rarely begins with a title or image, but rather allows the title to emerge from events and gestures in the music. Her music is often characterized by vivid orchestration and energetic rhythms, which Tower attributes to eight years of growing up in Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. After focusing on sonority during the 1970s, Tower gave more attention to rhythmic aspects of music in the 1980s. Petroushkates (1980), for example, not only quotes from Stravinsky's ballet but paraphrases the very fabric of his score, much in the manner of a sixteenth-century parody Mass.

Tower's early works were primarily chamber music, and many were composed for the Da Capo Chamber Players, which she founded in 1969 and in which she performed as pianist for fifteen years. In 1981 the American Composers Orchestra under Dennis Russell Davies presented the premiere of Sequoia (1979–1981), a commission by the Jerome Foundation. It was subsequently performed by the San Francisco Symphony under Davies, by the New York Philharmonic under Zubin Mehta, and by several major orchestras under Leonard Slatkin. After the St. Louis Symphony (directed by Slatkin) recorded Sequoia in 1984—the first of several recordings of her compositions—Tower was named composer-in-residence with this orchestra (1985–1988).26 Her increased visibility since 1981 demonstrates the career importance of writing symphonic works that receive performances by major orchestras led by established conductors. Since the success of Sequoia, her first orchestral composition, Tower has focused on this arena in such works as Music for Cello and Orchestra (1984); concertos for piano (Homage to Beethoven, 1985), flute (1989), and violin (1992); Concerto for Orchestra, a joint commission with premieres in 1991 (St. Louis), 1992 (Chicago), and 1994 (New York); and Duets (1994), premiered by the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra in 1995. Tower won the 1990 Grawemeyer Award, a $150,000 prize for a large orchestral work, Silver Ladders (1986). Tower's Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman (1986) began as a tribute to Aaron Copland and is now generally perceived to be a feminist response to his Fanfare for the Common Man. In less than a decade its popularity spawned four additional fanfares, including one for the centennial of Carnegie Hall (No. 3, premiered by the New York Philharmonic in 1991). By 1997 more than two hundred ensembles had performed the first fanfare. According to Tower, the series of fanfares aims “to honor women who are adventurous and take risks.”27 In May 1998 Tower herself was honored with induction into the American Academy of Arts and Letters for her outstanding achievements in music.

Barbara Kolb

Barbara Kolb's (b. 1939) handling of serial techniques in Appello (1976) for piano shows how a personal style can emerge from this compositional procedure. Each of the four movements of Appello is based on a series from Book 1a of Pierre Boulez's Structures (1952), and the third movement “involves a strict time-point organization for control of the rhythmic acceleration that progresses throughout the movement.”28 Appello, however, stands in sharp contrast to Boulez's Structures. Kolb's composition is a rich, often dense, expressive work in comparison to the sparsely pointillistic Structures. Kolb integrates serialism into a larger stylistic repertoire that combines the performer's freedom (in dynamics, pedaling, and indeterminate clusters) with the composer's control. As in many of Kolb's compositions, texture and timbre in Appello remain extremely important expressive means. Her choice of title, which means “call” in Italian, and the poetic references at the beginning of each movement suggest a focus on expressive import, while Boulez's title and subdivisions are pointedly abstract. According to Kolb, each movement is a different call—one that is “reaching and enticing, rather than insistent or demanding.”29

SOUND-MASS

During the first several decades of the twentieth century the domination of music by functional tonality was challenged in a number of ways. Initially these procedures preserved pitch as the foreground compositional element, but gradually compositions refocused attention on other parameters. Sound-mass minimizes the importance of individual pitches in preference for texture, timbre, and dynamics as primary shapers of gesture and impact. As part of the exploration and expansion of sonic materials, soundmass obscures the boundary between sound and noise. Emerging from tone clusters in piano works of American experimentalists in the early twentieth century, sound-mass moved into orchestral composition most noticeably by the late 1950s and 1960s. Many works that involve sound-mass also include other aspects of sonic exploration, such as the extensive use of muted brass or strings, flutter tonguing, wide vibrato, extreme ranges (especially highs), and glissandos (a form of microtonal writing). Early choral explorations of sound-mass occur in Sound Patterns (1961) by Pauline Oliveros and From Dreams of Brass (1963–1964) by Canadian composer Norma Beecroft (b. 1934). Beecroft blurs individual pitches in favor of a collective timbre through the use of vocal and instrumental clusters, choral speech, narrator, and a wash of sounds from an electronic tape. Both Barbara Kolb and Nancy Van de Vate have written compositions that rely heavily on soundmass; however, their compositions also include an array of sources melded into personal stylistic syntheses.

Barbara Kolb

Continuing the American experimental tradition, Kolb has focused her more recent compositional activity on unconventional ensembles as much as on unorthodox styles. Although she has written for solo piano (Appello, see above) and occasionally for full orchestra, many of her compositions are for nontraditional chamber ensembles, some with voice. She has also created a series of works combining prerecorded (nonelectronic) sounds with various instruments: for example, Spring River Flowers Moon Night (1974–1975), for two live pianists and a tape that involves an unusual group—mandolin, guitar, chimes, vibraphone, marimba, and percussion; Looking for Claudio (1975), with guitar and tape of mandolin, six guitars, vibraphone, chimes, and three human voices. Stylistically, both her stimuli and her creations are diverse. Three Place Settings (1968) offers unusual wit and humor in a three-movement work for violin, clarinet, string bass, percussion, and narrator; Trobar Clus, to Lukas (1970) borrows a repeating structure from the eleventh or twelfth century; Solitaire (1971) uses quotations from Chopin; Homage to Keith Jarrett and Gary Burton (1976) draws on jazz and improvisation; Cantico (1982) is a tape collage for a film about St. Francis of Assisi; and Millefoglie (1984–1985)30 combines computer-generated tape with chamber orchestra.

In Crosswinds for wind ensemble (1968) Kolb makes extensive use of sound-mass as she explores the metaphorically loaded title. The work unfolds after the opening segment presents the principal gestures of the whole. Relatively stable blocks of sound (later with more flutter and motion) alternate with soloistic lines suggesting chamber music. The use of mutes creates greater unity between brass and woodwind timbres, contributing to the indistinct plurality of the sound-mass and highlighting timbre and density as the primary compositional elements. The release after the first major climax exposes a single saxophone, reminiscent of the opening bassoon solo in Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring. Here again Kolb writes for an ensemble outside the musical establishment.

During the 1990s Kolb has composed more frequently for larger ensemble, and her style is sometimes more accessible—a shift common to many composers in the United States. In Voyants for Piano and Chamber Orchestra, premiered by Radio France in 1991 and subsequently revised and expanded for publication, Kolb creates a musical narrative with the piano functioning as the seer or prophet mentioned in the title.31 All in Good Time, commissioned for the 150th anniversary of the New York Philharmonic in 1994, was premiered under the baton of Leonard Slatkin, who has led subsequent performances with major orchestras. Texture and timbre remain important elements, along with rhythmic development and a hint of jazz, especially apparent in the central section for saxophone solo decorated by vibraphone and bass clarinet. Coupled with minimalism, jazz elements are more apparent in the ballet score New York Moonglow (1995), premiered by jazz notable Lew Tabackin on tenor sax and flute, along with five other musicians. Kolb's dense textures in the outer sections were supported by multilayered choreography, and Tabackin's improvised solo was matched by choreographer-dancer Elisa Monte's own improvisation. Music for the ensemble is fully notated, whereas Tabackin's part is both notated and left to improvisation.

Nancy Van de Vate

Nancy Van de Vate (b. 1930), whose catalogue is large and varied, has pursued an active career as a composer, educator, and promoter of contemporary music. In the mid-1950s she redirected her plans to be a professional pianist when she moved to Oxford, Mississippi, with her husband and child. She felt performance opportunities were limited there and that she could not commit to the necessary daily routine of practice: “I changed to composition, then became so totally engrossed in it that I never again wished to direct the major part of my time and energy to any other aspect of music.”32 Van de Vate taught piano privately and then at several colleges and universities throughout the southern United States and in Hawaii. After leading the Southeastern Composers League for a decade, she founded the League of Women Composers in 1975 (renamed the International League of Women Composers in 1979) and served as its chair for seven years. While living in Hawaii and then in Indonesia for nearly four years (1982–1985), Van de Vate developed an enthusiasm for Asian musics, which can be heard in the colorful orchestrations of works such as Journeys (1981–1984) and Pura Besakih (Besakih Temple, Bali; 1987). In addition to massive textures, Journeys combines minimalist aspects, a melodic focus of the soloists' lines, extended string sonorities, an enlarged percussion battery (especially mallet instruments), and the development of motivic material (C, B, C, Db). Like Kolb, Van de Vate integrates many different techniques and styles. Van de Vate, who in 1985 took up residence in Vienna, Austria, has expressed a desire to communicate with a broad public and has worked toward this not only in her compositions but also through her involvement as artistic director for Vienna Modern Masters, a recording company that produces an extensive catalog of contemporary music.33

Chernobyl (1987)34 and Concerto No. 2 for Violin and Orchestra (1996) are among Van de Vate's works for orchestra that utilize sound-mass. According to Van de Vate, Chernobyl was written “to express universal feelings about that event [an explosion at the Soviet nuclear power plant at Chernobyl] and its meanings for all peoples…. [It] is not intended to tell a story, but rather to evoke images and feelings.”35 The first half of the composition layers coloristic, dense, static clusters; the second half is more diatonic and conventional in the treatment of harmony, rhythm, and melody. A descending minor second, which Van de Vate calls a “weeping motif,” is prominent during the second section. It evokes the closing of the Revolution Scene in Modest Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov, where a similar string figure of repeated pairs frames the short conclusion sung by the Simpleton. In a prophetic lament, the Simpleton, alone on stage, warns of the impending disaster of war for the Russians. The affinity between these musical gestures is strengthened through the similarity of timbre, rhythm, pace, and range along with contextual links: the setting in Russia and the potential devastation. Van de Vate's Violin Concerto is a virtuosic work based on a symmetrical four-note cell (G, Ab, Bb, Cb) and reveals much contrast within the unified one-movement form. During the late 1990s Van de Vate has concentrated her compositional activities on opera, another large form.

In addition to her commitment to large-scale works, Van de Vate has composed for other mediums. Two trios offer considerable contrast with the orchestral works just discussed: Music for Viola, Percussion and Piano (1976) and Trio for Bassoon, Percussion and Piano (1980, rev. 1982). Timbre remains an important compositional consideration—occasional clusters occur in the piano parts, the bassoon's upper range is explored, and percussion batteries add coloristic elements. However, tuneful melodies and periodic metrical organization also play important roles, and texture is not a primary component.

RESHAPING TRADITIONS

Julia Perry

Julia Perry's extensive catalogue reveals her familiarity with two worlds: the vernacular music of her African-American heritage and Western (neo)classical practices. Born in 1924, Perry linked her early works with their roots in spirituals and blues to the rural past of a colonized people (e.g., the vocal solo “Free at Last” [pub. 1951] and Prelude for Piano [1946, rev. 1962]).36 During the 1950s, while Perry lived in Europe, she abandoned the outward signs of African-American identity and shifted her artistic attention to European models, especially that of her teacher, Luigi Dallapiccola. Perry avoided the twelve-tone system but followed Dallapiccola's focus on motivic unity and the transformation of small melodic cells, using them as her central organizing principles (e.g., in Short Piece [1952, reorchestrated in 1962 and 1965] and Symphony No. 1 for violas and double basses [1961]).

With growing racial awareness emerging from the Civil Rights struggles of the 1960s, Perry returned to a focus on conspicuous issues of the black experience, transformed and reshaped to reflect her social reality. Contemporary urban referents are found in her programmatic titles and in the incorporation of rock 'n' roll and rhythm and blues styles. In the explicit racial components of Bicentennial Reflections (1977) for tenor and six instrumentalists, for example, she draws the audience's attention to race with visual and textual elements, which seem to be supported by the musical gestures. For example, Perry's manuscript prescribes that the three percussionists should be an “American Negro (dark complexion),” a “Chinese American,” and an “American-Aryan or Jew.” In the closing moments of this piece the percussion parts suggest the potential for violence and self-destruction in U.S. race relations, following the final line of text: “By the fountain of dreams flowing in red.”

Hailed as an individual of great promise, Perry was favorably recognized during her twenties with major awards, international study opportunities, publications, and favorable reviews. The 1960s, perhaps her most productive decade in terms of the quantity of large-scale compositions, brought Perry distribution of her music by established publishers and the release of three works on separate recordings by CRI. Although she had some major performances, including one by the New York Philharmonic, her public visibility and press coverage seem to have diminished. Sometime during the 1960s Perry developed serious physical health problems including acromegaly and later, probably in 1971, was struck by another grave tragedy: a paralytic stroke affecting her right side. Although she learned to write with her left hand and continued to compose, she lived her last years in seclusion and with diminished ability to work.

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich

In the midst of much experimentation and a proliferation of styles in the late twentieth century, the music of Ellen Taaffe Zwilich (b. 1939) continues the American symphonic tradition, with ties to neoclassicism and the great American symphonists of the 1930s and 1940s. Zwilich updates this tradition, yet she retains a primary focus on pitch, relies on recurring and predictable patterns, and employs developmental forms. Discussions of her music frequently mention both her craft and the music's appeal to concert audiences and musicians. Although handled conventionally, Zwilich's orchestration is often vivid, as heard in Celebration for Orchestra (1984), and her string writing virtuosic, as in Prologue and Variations for string orchestra (1983). Describing her recent works, K. Robert Schwarz wrote that Zwilich's “music has become increasingly tonal and consonant. Today it is neo-Classic in concision but neo-Romantic in intensity.”37

After completing a master's degree in composition at Florida State University, Zwilich moved to New York and worked as a freelance violinist. A year later, in 1965, she began a seven-year tenure with the American Symphony Orchestra, gaining important experience for her compositional activity. In 1975 she became the first woman awarded a doctorate in composition from Juilliard, where she studied with Roger Sessions and Elliott Carter, the most important influences on her music. Zwilich has developed a high-profile career with numerous commissions from large, prestigious musical institutions and performers. In 1995 she became the first appointee to the Carnegie Hall Composer's Chair.

In 1983 Zwilich won the Pulitzer Prize for music for her Symphony No. 1 (1982), becoming the first woman to receive this important recognition. The first movement of Symphony No. 1 (see HAMW, pp. 377–401), an organic elaboration of the initial fifteen measures, establishes tonal stability through motivic reiteration, decorated tertian harmony, and pedal points. The intervallic persistence of thirds (especially minor thirds) also contributes to its coherence. String Trio (1982), written at the same time, is noticeably more angular, abstract, dissonant, and virtuosic. A similar contrast between a large-scale public work and a more intimate composition is also apparent in a comparison between Symbolon (1988) for full orchestra and Double Quartet (1984) for two string quartets. Symbolon unfolds in broad, simple gestures, in contrast to the darker, more intense Double Quartet, which explores the concept of duality. Tension between D minor and D major persists until the final moments of the work, when D major is finally confirmed.

Since the mid-1980s Zwilich has created a substantial series of concertos, both for the standard instruments (piano in 1986; the Triple Concerto for piano, violin, and cello in 1995; violin in 1997) and for instruments infrequently featured as soloists with major symphonies (trombone in 1988; bass trombone, strings, timpani, and cymbals in 1989; flute in 1989; oboe in 1990; bassoon in 1992; French horn in 1993). According to Zwilich,

the concerto is an inherently dramatic situation with many analogies to the theatre. For instance, a soloist (protagonist) may have a cadenza (soliloquy) in which to voice his or her essential nature, but the full development of a character requires a dialogue with other strong characters. For this reason, I very much enjoy choosing a special orchestration for a particular solo instrument, aiming for strong but complementary orchestral forces.38

Her approach to the solo writing has been to work closely with each of the soloists—often prominent performers—who would premiere these works in an effort to combine virtuosity and idiomatic capabilities of each instrument and performer.

Libby Larsen

In the past twenty years, Libby Larsen (b. 1950) has become one of the most important and successful composers in the United States, with works for orchestra, dance, opera, chorus, theater, chamber ensembles, and soloists. Larsen, whose works are widely written about and commercially recorded, studied at the University of Minnesota with Dominick Argento and co-founded the Minnesota Composers Forum (now the American Composers Forum) in 1973. In addition to giving many performances throughout the United States and Europe, Larsen has served as composer-in-residence with the Minnesota Orchestra (1983–1987) and with a consortium of musical organizations in Denver, including the Colorado Symphony Orchestra (1997–1999). She won a 1994 Grammy for the CD The Art of Arleen Augér on which Larsen's song cycle Sonnets from the Portuguese (1989) for soprano and chamber ensemble is featured.39 Larsen, who claims Gregorian chant, rock 'n' roll, stride boogie piano, and music from radio and television are all among her musical influences, has frequently sought to update the traditions and sounds of the concert hall through the inclusion of vernacular music. For example, in Ghosts of an Old Ceremony (1991) for orchestra and dance, written in collaboration with choreographer Brenda Way, Larsen focuses on migration, from the physical westward movement of American pioneer women to the migration of sound between the early 1800s and the late twentieth century. This composition not only challenges the expectations of orchestral players and audiences, but it also contests stereotypic, romanticized views of westward expansion and brings to attention the particular hardships and losses faced by these courageous women. According to Larsen,

Sound, and the groups of musicians who represent it, have migrated as surely and strongly as all the other aspects of our culture. Sound, which began in monodirectional presentation in the concert hall, is now heard mixed through speakers coming from multi-directions. Noise has migrated into the domain of musical sound by means of the sampler. At the end of the 1800s, sound was dominated by the high registers of the violin sections. Throughout this century sound has relocated to the bass…with the proliferation of speakers, electric basses, electric drums and digital mixing.40

The dancers take center stage, while members of the orchestra perform from both sides of the stage, the side tiers, and the back of the hall. Some of the musicians remain in place, others relocate, and some disappear amid sounds that range from an old hymn tune to readings from diaries of pioneer women to electronic music.41 Piano Concerto: “Since Armstrong” (1990), premiered in 1991 by pianist Janina Fialkowska and the Minnesota Orchestra, is another example of Larsen's blending of styles. She describes this piece as a dinner party whose guests include Louis Armstrong, Maurice Ravel, Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, Jelly Roll Morton, and blues guitarist Robert Lockwood.

In a 1996 interview Larsen discussed the importance of rhythm for her style: “I believe that music springs from language of the people. I am intensely interested in how music can be derived from the rhythms and pitches of spoken American English.”42 Although applicable for all mediums, this approach is especially relevant for her vocal and choral works, many of which are settings of texts by women or about strong females. Some examples include The Settling Years (1988) for mixed chorus, woodwind quintet, and piano;43 Songs from Letters (after Calamity Jane) (1989) for soprano and piano; Eleanor Roosevelt (1996), a dramatic cantata for mezzo, speaker, mixed chorus, clarinet, cello, piano, and percussion; and Mary Cassatt (1994) for mezzo, trombone, and orchestra.

Chen Yi

Like the other composers in this section, Chen Yi (b. 1953) is committed to composing music that people wish to hear and musicians wish to perform. In addition to fusing music of the East and West, her main goal has been described as “the desire to create ‘real music’ for society and future generations.”44 Chen,45 the daughter of two medical doctors, began piano and violin lessons at age three. During the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s she practiced in secret and then spent two years doing forced labor in the countryside as part of her “reeducation.” When Chen was allowed to return to her home city of Guangzhou, China, at age seventeen, she became concertmaster and composer with the Beijing Opera Troupe, which specialized in westernized socialist-realist style. She also began studying Chinese traditional music and music theory. Finally, in 1977, Chen was able to enroll as a student at the Beijing Central Conservatory, and in 1986 she became the first woman in China to receive a Master of Arts degree in composition. That year she also arrived in the United States as a participant in the Center for United States–China Arts Exchange at Columbia University, which composer Chou Wen-Chung directs.

In 1993 Chen received her D.M.A. from Columbia and was appointed composer-in-residence with three San Francisco musical organizations: the Women's Philharmonic (which she helped overcome a serious fiscal crisis), Chanticleer, and the Creative Arts Program at Aptos Middle School. In addition to having a busy schedule of composing, Chen taught composition at Peabody Conservatory (1996–1998). In the fall of 1998 she joined the faculty at the Conservatory of the University of Missouri at Kansas City as the Lorena Searcey Cravens Missouri Endowed Professor in Composition.

Discussing her compositional style, Chen stated:

I want to speak in a natural way in my own language, and that is a combination of everything I have learned from the past—what I learned in the conservatory, and what I learned in the field collecting folk songs. It's all a source for my imagination…. If you just put them together as Eastern and Western, then it sounds artificial—they don't sound together. But if you can merge them in your blood, then they sound natural together.46

Reviewers consistently cite her success in bringing these musical traditions together and the exciting timbres she achieves. Duo Ye No. 2 (1987) for orchestra draws on pentatonic material and was influenced by a traditional song and dance form of the Dong minority in the Guangxi Province. After it was performed at Avery Fisher Hall by the Central Philharmonic Orchestra of China, JoAnn Falletta became the first American conductor to program Chen's work with her performance of Duo Ye No. 2 at the Kennedy Center in Washington. Other works that demonstrate Chen's vivid orchestrations include Sparkle (1992) for a mixed octet; Ge Xu (Antiphony, 1994) for orchestra; and Golden Flute (1997) for flute and orchestra. Chinese Myths Cantata (1996) for male choir, orchestra, and Chinese dance—a joint project between Chanticleer and the Women's Philharmonic—emerged as the culmination of Chen's residency program. A poignant and theatrical setting of three Chinese creation myths, it includes four traditional Chinese instruments: erhu (fiddle), yangqin (dulcimer), pipa (lute), and zheng (zither). During the second movement, the audience is encouraged to participate with nonsense syllables to contribute to the climax.47

SONIC EXPLORATION

The expansion of sonic resources during the twentieth century can be viewed as an intersection of events, including the enrichment of instrumental and vocal resources throughout the Western European tradition and the century's craving for newness. Further, independence of timbre as a primary compositional parameter emerges from what George Rochberg has described as the shift from a temporal to a spatial concept of music, and it is closely tied to the move away from a melodic-harmonic treatment of pitch material.48 By defining “acceptable” musical material, women have found resources to challenge cultural norms and the ideology of dominant culture, to reformulate gender constructions, to confront the gender identification of specific instruments, and to destabilize musical and social hierarchies.

Annea Lockwood (b. 1939) often challenges the line between music and noise in her compositions. While working in many genres, her compositions consistently focus on timbral exploration and performance, including spatial concerns. A native of New Zealand, Lockwood came to the United States in 1973 after living in England for twelve years. In the mid-1960s she moved away from instrumental music and synthesized electronic materials to work more with acoustic sound sources from nature. Her imaginative Glass Concert, performed many times from 1966 to 1973, uses diverse sizes and shapes of glass, which are struck, rubbed, bowed, and snapped:

I began to feel that electronic timbres, that is, the classic studio timbres, were simplistic by comparison with acoustic timbres and spectra, and not satisfying, not intellectually stimulating, not interesting to work with…. I needed to refine my hearing and my audio sensitivity…. What fascinates me still about acoustic phenomena is the large area of unpredictability about them.49

During the 1970s and early 1980s Lockwood focused on works for tape and pursued explorations of performance, including theatrical elements, ritual, and improvisation. Tiger Balm (1970) for tape effectively combines the acoustic sounds of a cat purring, a heartbeat, gongs, jaw's harps, tigers mating, a woman making love, and an airplane. Here, and typically, Lockwood's arrangement and selection of sounds are crucial since she uses the sounds unmodulated.

During the 1970s and early 1980s she also gave increased attention to events and installations, such as in The River Archive (recordings of rivers from around the world were collected over a period of years and presented in 1973–1980) and in A Sound Map of the Hudson River (1983), in which the musical parameters of rhythm, pitch, counterpoint, texture, and form are all apparent in the natural sounds of the fifteen locations along the Hudson. Since the mid-1980s Lockwood has returned to composition for acoustic instruments and voice. She has composed a number of solo works, including Amazonia Dreaming (1988), For Richard (1992), and Ear-Walking Woman (1996), plus chamber music such as Thousand Year Dreaming (1990) for four didjeridus, frame drums, conch shells, winds, and projections; and Monkey Trips (1995), developed with the California E.A.R. Unit.50

The range of timbres on acoustic instruments has multiplied during the second half of the century, and the literature mentioned here gives only a hint of the scope and breadth of activity. Lucia Dlugoszewski (b. 1934), whose Fire Fragile Flight (1974) was the first work by a woman to win a Koussevitzky International Recording Award (1977), invented the “timbre piano” in 1951. She has consistently worked with expanded acoustic sounds, using conventional and invented instruments. She composed Suchness Concert (1958–1960), which is concerned with Zen immediacy, and Geography of Noon (1964) for an ensemble of one hundred of her newly invented percussion instruments, built by sculptor Ralph Dorazio. Her Space Is a Diamond (1970) for solo trumpet virtually catalogues extended technique for this instrument.

Composer Anne LeBaron (b. 1953) is also an internationally recognized harpist who pioneered extended techniques, prepared harp, and electronic extensions of harp timbres. She breaks the stereotypes of harpists and harp music in works such as the solo improvisation Dog-Gone Cat Act (recorded in 1981) for prepared harp and in Blue Harp Studies (1991) with electronic processing. Whether for the unusually constituted LeBaron Quintet (trumpet, tuba, electric guitar, harp, and percussion) or for conventional ensembles, LeBaron's compositions consistently use evocative, colorful timbres. During the 1980s her vocabulary expanded through an increased use of microtones, world music, sounds from nature, electronics, and new instruments, for example, in Lamentation/Invocation (1984).51

Although some timbral exploration moves in the direction of noise and high intensity, other compositions highlight quiet, refined effects. Translucent Unreality No. 1 (1978) by Darleen Cowles Mitchell (b. 1942), for prepared piano, flute, and wind chimes, unfolds slowly and calmly, like the ephemeral flowers mentioned in its epigraph. Relative, nonproportional rhythmic durations contribute to the mood of fluid impermanence. From My Garden No. 2 (1983) by Ursula Mamlok (b. 1928), another delicate piece, is scored for oboe, French horn, and piano, with subsequent versions for viola or violin. The piano part includes pizzicato effects inside the instrument, and each performer also plays a crotale (a thick metal cymbal with definite pitch) by bowing as well as striking it.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, both percussion and the allied parameter of rhythm were largely untapped resources in music of the Western European tradition. Percussion now enjoys prominence through its own ensembles as well as an expanded role in orchestras and chamber groups. Before composing Amazonia Dreaming (1988), for solo snare drum, Annea Lockwood thought of this medium as limited; however, she discovered it is capable of making “wonderful, animal-like sounds…as well as great beauty in its own natural resonances.”52 Julia Perry's Homunculus C.F. (1960; see HAMW, pp. 335–44), scored for harp, celesta/piano, and an ensemble of eight percussionists, creates a precarious balance between pitch (melodic and harmonic) and rhythm. Although percussion is the principal timbre, the macrostructure is based on a single harmonic unit rather than on rhythm. And although the pitched instruments offer melody and create chords, the chosen instruments (harp, timpani, vibraphone, and even celesta) do not produce sounds with a particularly clear pitch focus. Further, harmonic gestures are virtually nonexistent despite the generation of pitch material from a single chord: a chord of the fifteenth (the “C.F.” of the title) rising from an E. Perry's title also derives from the scene in Goethe's Faust II in which Wagner, Faust's apprentice, brings Homunculus (literally “little man” in Latin) into being in a vial via alchemy. Perry described the work in figurative terms: “Having selected percussion instruments for my formulae, then maneuvering and distilling them by means of the Chord of the Fifteenth (C.F.), this musical test tube baby was brought to life.”53 Like the alchemy process, Perry's musical materials unfold gradually, and only the final phrase (mm. 171–180) builds in density to include all ten performers and all eight pitches. Homunculus “becomes” in a sharp flash. In addition to this surface narrative, Homunculus C.F. can also be analyzed in terms of a narrative focused on instability and on ambiguous roles, perhaps mirroring the insecurity of the experimental artist in contemporary society—particularly true in the case of an African-American woman during the early years of the Civil Rights movement.

Performers as well as composers have been active participants in extending sonic resources, particularly in cases of close collaboration (e.g., Bethany Beardslee and Milton Babbitt; Jan DeGaetani and George Crumb; Cathy Berberian and Luciano Berio). Interestingly, the leading vocalists of contemporary music and especially music with extended techniques are almost exclusively women, including performance artists Laurie Anderson, Joan La Barbara, and Meredith Monk. Many of the compositions exploring vocal resources also call for virtuosic performance skills and a reevaluation of text and the human voice as components of musical expression.

Jan DeGaetani (1933–1989), noted for both technical skill and artistic performances of contemporary music, surely influenced and shaped composition for voice. Jacob Druckman, Peter Maxwell Davies, György Ligeti, and Pierre Boulez composed works for her. The link between DeGaetani and composer George Crumb is particularly striking, covering more than two decades. She premiered and recorded most of his music for voice, including Madrigals (1965 and 1969) and Ancient Voices of Children (1970). As professor of voice at the Eastman School of Music and Artist-in-Residence at the Aspen Music Festival for many years, DeGaetani was influential on the next generation of performers.

Like DeGaetani, Cathy Berberian (1925–1983) was a virtuosic performer. Born in the United States of Armenian parents, she developed strong theatrical abilities, and her dramatic presence remained powerful even when illness forced her to perform from a wheelchair. Her vocal skills influenced compositions not only by Luciano Berio, her husband from 1950 to 1966, but also by John Cage, Igor Stravinsky (the final version of Elegy for JFK), and numerous Europeans (Sylvano Bussotti, Henri Pousseur, Bruno Maderna, Hans Werner Henze). A large portion of Berio's output was written for Berberian: Chamber Music (1953), Circles (1960), Sequenza III (1960s), and Recital I (for Cathy) (1972). Berberian's voice is also crucial in Berio's dramatic electronic works, Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) (1958) and Visage (1961), which both link violence and the erotic in disturbing ways. Even after their divorce Berberian and Berio continued to collaborate musically. Berberian's own compositions—Stripsody (1966), Awake and Read-Joyce (1972), and Anathema con VarieAzioni (1972)—were also written with her own voice in mind. Stripsody, which deals with comic strips as cultural discourse, is a collage verbalizing onomatopoeic words from the comics. Inserted into this witty texture are very short scenes from comic strips (e.g., “Peanuts”) or stereotypic movie scenes.54

PERFORMANCE ART AND EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC*

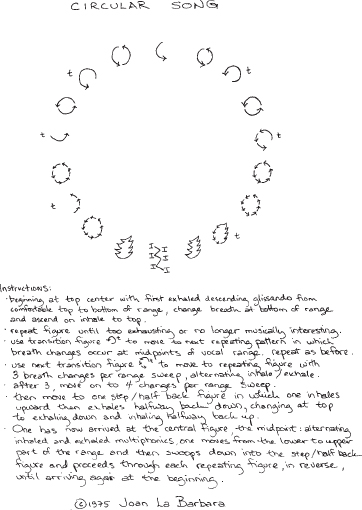

Pushing the boundaries of performance and composition still further, performance art unites the roles of composer and performer and generally incorporates a variety of media. Theatricality, vocal experimentation, multimedia events, Eastern philosophy, dance, and storytelling are among the elements included in its stylistic and musical diversity. Performance art, along with minimalism and neotonality, was one of the new directions of the 1980s that sought to reengage the public. A performance artist par excellence, Laurie Anderson has been especially active in this field. Composers Pauline Oliveros and Meredith Monk both have created numerous pieces that fall under this heading. Joan La Barbara, not a performance artist per se, has been active as a collaborator with avant-garde musicians and has developed an extended vocal technique that earns her the title of experimental musician/composer.

Diamanda Galás

The work of composer–performance artist Diamanda Galás (b. 1955) transgresses many norms, and its unconventional timbres are meant to provoke and to challenge the ideology of dominant culture. Her work is guerilla art. Galás's extraordinary Plague Mass (1989) is an anguished cry of outrage for persons living with AIDS. Bathed in red stage lights and covered with a bloodlike substance, Galás appropriates almost earsplitting screams—high, sustained, and raw—to condemn the treatment of people with HIV and AIDS and to denounce U.S. policy and the response to the AIDS crisis. Her performance is riveting and pushes the boundaries of music or any art form. In the words of Richard Gehr, “She demonstrates how an activist artist can push the limits of acceptable social responses, challenging the status quo.”55

In her music Galás utilizes an extensive personal background: keyboard prodigy, jazz singer, and avant-garde vocalist for European composers such as Vinko Globokar and Iannis Xenakis. She also draws on her Greek heritage through the use of gestures and sounds of Maniot women's mourning. The Maniot, like Galás, used their mourning incantations, called moirologi, as a political force: these Greek women would scream and pull out their hair in order to incite people to revenge. Galás acknowledges that these women were considered a threat to the authority of patriarchal society,56 their incantations “a form of empowerment for the women—an enactment, an assumption, of the power of death.”57 In Plague Mass, the shocking sounds of Galás's lamentation push us as listeners to share her outrage and spur us to political action. In other works Galás has undertaken further wrenching topics in equally compelling ways. Vena Cava (premiered in 1992) explores themes of psychological claustrophobia and solitary confinement as manifest in people with mental illness or AIDS-related dementia. Performed in total darkness, Schrei 27 (1994) and Schrei X (1995), whose titles mean “shriek/scream” in German, address the interior isolation experienced by a person who is tortured or subjected to sensory deprivation. These two works juxtapose high-intensity vocal sounds with absolute silence.58

Pauline Oliveros

Theatricality, humor, feminism, meditation, audience participation, and experiment all are important aspects of the music of Pauline Oliveros (b. 1932). Her family was musical: her mother and grandmother taught piano, and her grandfather collected musical instruments. After studying piano with her mother, Oliveros took up her brother's instrument, the accordion. Later she learned tuba and French horn, but her lifelong affinity with the accordion has remained central to her compositions and improvisations. Her studies at the University of Houston (1949–1952) included accordion and composition. From Houston she transferred to San Francisco State College to study composition with Robert Erickson, and received her B.A. degree there in 1957.

Oliveros's early works show a tendency toward experiment. Her Trio for Flute, Percussion, and String Bass (1963) has a Webern-like texture but uses nontraditional notation, with and without indicating exact pitches. In contrast, Aeolian Partitions (1970) has approximately one page of notated music and several pages of instructions, including a list of the required performers and their props (a broom for the cellist, a newspaper and flashlight for the pianist, etc.) and a very detailed scenario. Aeolian Partitions also calls for telepathic improvisation.

Each performer concentrates on another single performer. When he hears an interval or a chord mentally, he plays one of the pitches and assumes that he is sending the other pitch or pitches to the other performer by mental telepathy.59

Aeolian Partitions is one of many theatre pieces Oliveros has written. Her earliest work in this genre was Duo for Accordion and Bandoneon with Possible Mynah Bird Obbligato (1964). She added her pet mynah bird because it joined in during rehearsals; since the bird added a visual element, Oliveros asked Elizabeth Harris to design stage sets. Harris created a wooden seesaw with revolving chairs, which made reading a score impossible; so Oliveros replaced her original music with a set of simple instructions. The instructions for Pieces of Eight (1965) are more elaborate, calling for stage movement, costumes, cash register, skull and crossbones, and a bust of Beethoven with flashing red lights for eyes. Other theatre pieces include George Washington Slept Here, Participle Dangling in Honor of Gertrude Stein, Double Basses at Twenty Paces, and Link (renamed Bonn Feier).

Oliveros has also experimented with electronic music. In 1961, along with Morton Subotnick and Roman Sender, she founded the improvisation group Sonics, later renamed the San Francisco Tape Music Center. When the Center, now called the Center for Contemporary Music, relocated to Mills College in 1966, Oliveros became its director. Her commitment to electronically produced sound has influenced even her music for traditional performance forces. Sound Patterns (1961), which won a Gaudeamus prize, calls for an a cappella choir, yet it mimics tape devices such as white noise, filtering, ring modulation, and percussive envelope. Bye Bye Butterfly (1965) is an improvised piece realized by Oliveros with two oscillators, two live amplifiers, a turntable, a recording of Puccini's Madama Butterfly, and two tape recorders in delay setup. In 1966 Oliveros experimented with compositions whose fundamental tones were outside the range of human hearing, so that the only musical sounds perceived were the overtones. This use of subaudio and supersonic oscillators to create music was so unprecedented, says Oliveros, that “I was accused of black art.”60 Her I of IV is based on the very nature of electricity.61

In the early 1970s Oliveros became involved with T'ai Chi, karate, dreams, mandalas, and Asian culture. Through a synthesis of her study of consciousness, martial arts, and feminist sociology she developed a theory of sonic awareness in which the goals of music are ritual, ceremony, healing, and humanism; beauty, rather than the goal, is the by-product. Using a parallel to Jung's viewfinder archetype based on sound—sound actively made, imagined, heard at present, or remembered—Oliveros created twenty-five Sonic Meditations. The three most suited to beginners appear in HAMW, pp. 364–66. The first, “Teach Yourself to Fly,” is an exercise in tuned breathing; Meditation XIV, “Tumbling Song,” calls for descending vocal glissandi beginning at any pitch. “Zina's Circle” (Meditation XV) is more complex and involves hand signals between the performers. All three of these Sonic Meditations call for the participants to stand or sit in a circle formation; there is no separate audience.

Though Oliveros wrote her Sonic Meditations for participants only, she incorporated some of their elements into pieces intended for public performance. In the ceremonial mandala piece MMM, a Lullaby for Daisy Pauline (1980), for instance, she invited the audience to participate with humming sounds and audible breathing.62 Still later works hark back to earlier compositional techniques. At a 1985 performance of Walking the Heart, the hall illuminated only by candles, the whirling dancer, and the digital delay device recalled both the theatrical aspects and the electronically manipulated sounds of her early works. The Roots of the Moment employs not only an interactive electronic environment but also an accordion tuned to just intonation.

In 1985 Oliveros established the Pauline Oliveros Foundation, based in Kingston, New York. This nonprofit organization supports creative artists worldwide via residencies, international exchanges, the creation of new works, and an active performance schedule.63 Its mission is to explore new technologies and new relationships between artists and audiences.64 Prominent performers on the Pauline Oliveros Foundation's concert schedule are the Deep Listening Band and the Deep Listening Chorus. Aligned with Oliveros's Sonic Meditations, the Deep Listening pieces are intended to help musicians, trained and untrained, to concentrate on closely listening to one another. Oliveros explains, “Deep Listening is listening in every possible way to everything possible to hear…. [It] includes the sounds of daily life…one's own thoughts…musical sounds. Deep Listening is a life practice.”65 In 1992 the National Endowment for the Arts supported the composition of Epigraphs in the Time of AIDS for the Deep Listening Band. The same year Tokyo hosted a five-hour, multimedia Deep Listening marathon.

Deep Listening also underlies the collective improvisations of Oliveros (accordion and voice), Stuart Dempster (trombone and didjeridu, an Australian aboriginal trumpet of wood or bamboo), and Panaiotis (voice, found percussion) in music recorded in the Fort Worden Cistern in Port Townsend, Washington. Oliveros describes the process:

Each composer [Dempster, Panaiotis, and Oliveros herself] has a very individual style of composition. As we improvise together, and listen intensely to one another, our styles encounter in the moment, and intermingle to make a collective music…. Listening, not only to one another but to the transformative spatial modulations, is an essential process in the music. The cistern space, in effect, is an instrument played simultaneously by all three composers…. The tonal qualities produced by each performer are constantly changed by interaction with the cistern acoustics, making it seem as if many more instruments are present.66

Lear, one of the pieces created by this process, was used in Act V, iii, of Shakespeare's play as produced by Mabou Mines.

Oliveros has won a respectful following, among composers and audiences, as an experimenter and a forerunner in the now widely accepted field of electronic music. Through her many residencies at colleges and universities she has spread to a younger generation of composers her ideas about creating a music based on listening. Her concern with meditation and Eastern philosophies recalls the ideas of John Cage, though her music does not. Most poetically stated, Pauline Oliveros is, in her commitment to feminist principles and her exploration of new language of sounds, a musical Gertrude Stein.67

Laurie Anderson

Laurie Anderson (b. 1947), unlike the other musicians in this section, never had to give up a preconceived style of composition. As a young adult she was a student not of music but of art history and sculpture, though she had studied violin throughout her youth. In reaction to her sculpture and performance art, with its great emphasis on music and sound, her teachers at Barnard College and Columbia University used to ask her if she were in the wrong department. One early sculpture looked like a mere table. With elbows resting on the table and hands cupped over the ears, however, the viewer could hear music. Anderson began making her own instruments in 1974.

Both sound and the art of the storyteller have always been integral parts of Anderson's work, and her music has very often served a story. To this end the visual element is ever important. As is true of some of Meredith Monk's work, Laurie Anderson's performance art can be appreciated most fully when one sees her perform. With the magical-elfin quality of the spectacle she creates, Anderson is truly an entertainer. In O Superman, a video, a light placed inside her mouth shows eerily through closed lips and glows when she opens her mouth to sing. In live performance her charm, wit, inventiveness, and intellectual sarcasm—when at its best—captivate audiences. By means of slide projections, film, video, altered vocal sounds, and various self-invented instruments, Anderson and her concerts have taken on the alternating qualities of comedy club, rock concert, and magic act. In the sophistication of her stories Anderson is a modern minstrel or “Multi-Mediatrix.”68 Many of her tales are partly autobiographical.

In the 1970s Anderson performed throughout the United States and Europe in art galleries and museums, including Berlin's Akademie der Kunst, settings where she could use intimate lighting effects. For example, she once projected a slide out of sight onto a ceiling. When she whisked her violin bow through the beam of light, for an instant the image came into view. She also created haunting music using a violin equipped with a tape-recorder head. Music sounded when her bow, strung not with horsehair but with prerecorded magnetic tape, touched the head. The song “Juanita” uses such a violin. Still another self-invented instrument, a white electric violin, sounds like thunder when played with a neon bow.

Anderson's magnum opus, the four-part, two-evening United States I-IV, was given its premiere in 1983 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. This set of “visual songs” took several years to create and was intended “to make a portrait of a country,” says Anderson. “At first I thought it was just the United States, but it's not turning out to be that way. It's a portrait of any highly technological society.”69 The work was inspired by the many questions people asked Anderson about her country while she was on tour in Europe. It is documented both on record and in book form.70

Anderson has also written music for choreographers, such as Long Time No See, which was made into the dance Set and Reset (1983) by Trisha Brown. Anderson's work often has a very feminine, even feminist, undercurrent. The lyric from Example #22, sung in a pathetically painful tone of voice, provides one instance: