According to the New York Times, most nursing homes had fewer nurses and caretaking staff than they reported to their state and county governments.1 In the fifty states, nearly 1.4 million people are cared for in skilled nursing facilities. When such nursing homes are short-staffed, nurses and aides scramble to deliver meals, ferry bedbound residents to the bathroom, and answer calls for pain medication. Essential medical tasks such as repositioning a patient to avert bedsores may be overlooked when workers are overburdened, and this may lead to an otherwise avoidable hospitalization. So who is looking out for the elderly, taking their abusers to court, forcing nursing homes, hospitals, and HMOs to maintain state-mandated staffing levels, and compelling these institutions to compensate their patients when they fail to follow the law? Men like Russell Balisok rise to the occasion.

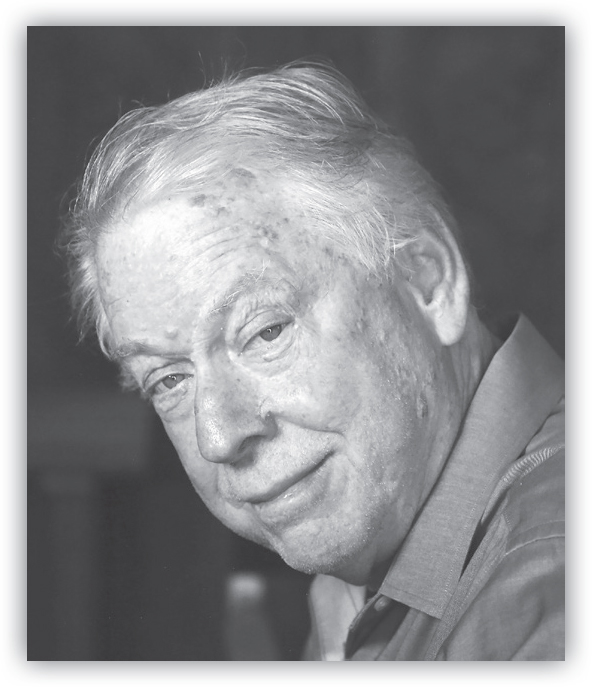

Russell Balisok of Los Angeles is one of the few attorneys in his field. In the state of California, none have done more to force the medical and long-term care community to live up to their legal obligations. He’s also authored enforcement legislation and helped guide it through the state assembly and senate into law.

But let’s start at the beginning.

Balisok was born and raised in South Central Los Angeles in 1946, when its neighborhoods were an ethnic stew of whites, Mexican Americans, and African Americans. After high school, he enrolled at California State University, Los Angeles.

“I grew up in a one-parent home with a schizophrenic older brother. It was pretty brutal, and it took me quite a long time to really deal with all of that,” Balisok said. “I was a poor student from a middle-class family, hence I enrolled in Cal State LA.”

He didn’t stay long, however. “Rather than quit, I took the easy way and flunked out,” Balisok recalled. “I was not interested in school.”

On February 15, 1966, Balisok received a draft notice and was sent to basic training at Fort Hood, Texas. He volunteered for advanced infantry training and emerged from this eight-week course as a heavy-weapons infantryman.

He believed he would soon be sent to Vietnam, so he volunteered for officer candidate school and thought the war would be over by the time he graduated. He became an infantry second lieutenant on March 27, 1967, at Fort Benning, Georgia. “That was the worst time of my military career; that was brutal.”

Thus, the US Army, as it has for centuries, took a feckless schoolboy and in less than a year turned him into a man and then an officer and a gentleman. As much as Balisok had expected to delay his visit with South Vietnam’s unfriendly environs long enough to avoid them altogether, the war continued to boil on. So he applied for flight school. He thought the conflict would be resolved before the next eight months passed, before he learned to fly a helicopter well enough for the army to risk sending him to war.

While his application went through channels, Balisok returned to Fort Hood for four months of seasoning in a mechanized infantry company of the First Armored Division. Then his application was approved, and Balisok went to Fort Wolters, Texas, for primary helicopter training as part of Flight Class 68-4, with graduation scheduled for April 1968. Just before he completed flight training at Fort Rucker, Alabama, Balisok was promoted to first lieutenant, and the war in Vietnam showed no sign of ending. His orders for the war zone came almost immediately after graduation.

By then, Balisok’s wife, Dorothy, was pregnant. “She wrote to President Johnson complaining that the war would take her husband away at a time when he should be there for the birth of his first child,” Balisok recalled. “I was diverted to Fort Riley, Kansas, to allow me to be present for the birth,” he said. “My job there was to find outdated post regulations, figure out who to circulate them to for comment, then take the comments, redraft them, and then circulate them again. Once they came back clean, I sent them to somebody to sign, and we had our new post regulations.”

He was also required to maintain flight status by flying one of the post’s few helicopters four hours a month. And as an additional duty, Balisok inspected all military funeral details in the state. “The remains of men killed in action were returned to their homes in Kansas. I flew to each locale and observed the funeral detail, then reported any irregularities. That was not good training for a young man on his way to Vietnam, I can assure you,” he added.

“My daughter was born in July 1968,” he recalled. “There were two other officers from my flight class who were in the same situation, with new kids.”

Weeks went by after his daughter’s birth with no word about his new assignment. “We met and called the Pentagon’s infantry aviation assignments desk to find out why we were still at Fort Riley,” Balisok explained. “That was, of course, the first really major mistake of my military career. Had I not called, I might still be there.”

The army had somehow lost track of Balisok and the two other new fathers. “This was well before computers,” he explained. “I spoke to a lieutenant colonel named Kastner, who was in charge of infantry aviation assignments. I said, ‘I’m here with my two buddies, and we’re interested in finding out what’s going on.’”

Kastner said, “What’s your name again?”

Balisok told him, and three minutes later Kastner came back on the line and yelled, “Where are you?” When Balisok said he was at Fort Riley, Kastner said, “You’ve got orders to Fort Bragg and you’re AWOL.”

Balisok responded that he had not received those orders, and after a certain amount of swearing, Kastner said, “Okay, okay, okay. Who are the other two guys?” After Balisok told him, Kastner said, “They’re AWOL too! We’ve got to get this cleaned up.”

The three of them shipped out to Fort Carson, Colorado, where they joined an aviation battalion being formed to round out the 101st Airborne Division in Vietnam, which had deployed to the war zone as an airborne unit. It was then in the process of being reconfigured as an airmobile division, which included adding hundreds of helicopters. The division was redeploying from the Central Highlands to an area near the DMZ to allow some marine units that had taken a beating at Khe Sanh to move south, where they would refill their depleted ranks with replacements. Balisok was a tiny part of a huge, strategic reconfiguration of all US forces in South Vietnam.

At Fort Carson, Balisok was assigned to the 158th Aviation Battalion. “Our unit, Bravo Company, was the last of the four companies to deploy.” An aviation battalion was then comprised of three Huey “lift” companies, with the mission to transport infantry into battle, and one gunship company. Balisok said, “When I reported to the battalion, Major Robinson, the S1,2 assigned me to the gunship unit, which flew heavily armed Cobras. I asked to go instead to a lift company. I didn’t want to go home to my family after flying Cobras for a year and have images of killing people in my mind. I would be happy just to take troops in and out and support them. I accepted the risks of that, but I didn’t want to fly a Cobra.”

Robinson understood. One of the other new guys, Billy Higgins, wanted to fly Cobras. So they switched.

Balisok’s most dangerous mission came soon after deployment.

“My second mission was to take a Special Forces team comprised almost entirely of Montagnards and Chinese Nung mercenaries across the border into Laos. That required ten aircraft from different units. I flew number seven, call sign NAT 7. We were led by NAT 1. The mission commander decided that one ship at a time would approach over the open field to a hole in the jungle canopy, hover down into a bomb crater, drop our passengers, and then climb out.”

What could go wrong? “Well,” Balisok explained, “the open area was a free-fire zone for an NVA battalion. I heard the first guy taking hits. It sounded like someone banging on his aircraft with a hammer really fast. The pilot was yelling and screaming as he made the approach. Once below the canopy level, he was fine. Then he had to hover down into the bomb crater; otherwise, the helicopter was too high for people to jump safely.

“That was the first guy. I was number seven. Everybody before me was shot up. I took hits all the way over and down into the hole. One shook the aircraft so hard it seemed like we were inside an unbalanced washing machine. Finally, we’re in the crater, and we dropped off our people.

“As I climbed out, I got a radio call, ‘Any NAT aircraft, NAT 1.’

“Nobody answered. He called again. No answer. Finally, I responded. ‘NAT 7.’

“‘NAT 1 . . . NAT 4 chickened out. He put his folks off to the east someplace. Go pick them up and deliver them.’

“So we went back a second time, but it wasn’t so bad because the NVA had pretty much run out of ammunition.

“We put the second bunch down, went back, and set the aircraft down and found thirty-eight 7.62mm bullet holes and one .50-caliber hole—fired from a hilltop above the jungle canopy—six inches from the main rotary tension pin through the main spar of the rotor blade. There were also two bullet holes, four inches apart, in the bulkhead, just above my door gunner, right where his face would have been.”

Balisok’s worst experience in Vietnam, however, didn’t involve his own peril. In the first days of his tour, before his company’s aircraft arrived, he and his men spent most of their days filling sandbags and building revetments to protect their sleeping area and their parked aircraft.

“One day I had some extra time, so I went to the MARS station3 and called my wife. Waiting my turn, I sat next to Lt. Col. Weldon Honeycutt, commander of the Third Battalion, 187th Infantry. He said this was his second tour and that the men now fighting the war didn’t know what they were doing. Didn’t know what it meant to be in a real combat situation. Didn’t know what it meant to be tough. While he was talking, I was thinking that I hope we never find out, but if we do I’m sure we’ll do our job.”

For ten days after May 10, 1969, Balisok and his aviation company supported Honeycutt’s battalion, 3/187, and other US units as they fought at Hill 937, which came to be known as Hamburger Hill. While the hill was of no strategic importance, atop that hill and in bunkers all the way up its steep slopes was a large NVA force.

Before the first American or South Vietnamese soldier set foot on the hill, it was bombarded for two hours by close-support aircraft. That was followed by ninety minutes of artillery fire.

Then the 187th and the First ARVN Division’s Second Battalion, Third Infantry attempted to take the jungled height by frontal assault. “On Honeycutt’s orders, his battalion continuously sought to assault Hamburger Hill,” Balisok recalled.

Balisok and his platoon brought in ammunition, food, and water. They also ferried reinforcements into the battle and evacuated the dead and wounded.

“He just kept sending his guys into a meat grinder,” Balisok recalled. The result was predictable: squad by squad, platoon by platoon, company after company, the Third Battalion, 187th Infantry took frightful casualties.

It required ten days and four additional US and ARVN infantry battalions to clear the hill. The ARVN 2/3 reached the crest of Hamburger Hill at 10:00 a.m. on May 20. Instead of attacking the NVA troops below them from the rear, an enemy formation then punishing what was left of Honeycutt’s battalion, the 2/3 was ordered to withdraw from the summit. Artillery then pounded the hilltop. After taking still more casualties, the 3/187th broke through the NVA and occupied the hilltop, which created the illusion they alone had taken Hamburger Hill. The battle became a subject of congressional hearings, and the commander of US forces, Vietnam, changed his strategy to prevent another such senseless loss of American lives.

Honeycutt, however, was rewarded for his men’s sacrifice. He went on to become a major general.

“Three weeks later, after we abandoned Hamburger Hill, the enemy walked back onto it without firing a shot,” Balisok explained. “It had no military significance except that it was there and there were people there to defend it, so we had to attack it. That was the story of Vietnam.

“Later I made friends with some of the guys who were on Hamburger Hill,” Balisok recalled. “I’m certain anyone in that battalion would have killed Honeycutt if they got a chance.

“That part of my Vietnam experience followed me around for twenty-seven years,” Balisok continued. “I had a nightmare about this guy every night during those years: I crouched outside Honeycutt’s quarters with my pistol, and at 4:00 a.m. he comes out, and I kill him and then walk away. Same nightmare for twenty-seven years. I finally put that away.”

Balisok lost one man, a crew chief hit by a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) during an assault landing on his first combat mission. He completed his tour without another man killed or wounded, surely a testament as much to leadership as to luck.

After completing his service in Vietnam, Balisok returned home. Things were different. “I lost almost all my friends,” he recalled, “because they disapproved of my Vietnam service.” And Balisok was “quite dedicated and interested in school. I persuaded Cal State University to accept me on probation. I made straight As from then on. After I graduated, I was lucky enough to talk my way into Southwestern University (a Los Angeles law school) at the last minute.”

Which brings us back to Balisok’s career as an advocate for the abused elders of California and elsewhere. In 1975, he graduated from law school and passed the bar. He couldn’t find a job with a law firm, because Vietnam veterans were pariahs and because Southwestern Law School graduates were regarded as only a little better than Vietnam veterans.

He opened an office and joined the lowest class of attorney: sole practitioners. He also took a job at Southwestern, teaching first-year students research library and legal writing skills. “It was kind of like a homeroom for law students,” he joked.

In the 1980s he made a living with a practice that was mostly real estate and “meat-and-potatoes” business litigation. “One day in 1982,” he said, “in walked two families referred to me by my secretary’s mother, who worked for Jewish Family Services in Los Angeles (a free, nondenominational social services organizational). They told me what had happened to each of their mothers in nursing homes that led to their deaths.

“I was struck dumb that this could even happen. Until then I hadn’t handled personal injury cases, but their stories were so affecting that I almost cried with them,” he said. Then he went home and told Dorothy about it, and this time he did cry. “I was shocked by the depraved conditions those two mothers were subjected to. I decided that I would try to make a career suing nursing homes.”

Balisok worked for nearly seven years before winning a case. “Two years later, coincidentally, the California legislature enacted the California Elder Abuse Act, which made the cases I had been handling economically viable.” Barely viable, but enough to allow Balisok to continue. “As time went by, I realized I could sue all the nursing homes in the world—and their doctors, for that matter—under the Elder Abuse Act, but nothing would change unless I could make the Elder Abuse Act apply to the people who were actually paying for the care, namely, the HMOs and hospitals that provide Medicare nursing home benefits to enrollees and sometimes prefer profit over proving contracted services.

“The difference between collecting from one nursing home and collecting from the much deeper pockets of HMOs was that the HMOs actually select the nursing homes they place patients in. In effect, they are encouraging or tolerating policies that no nursing home should tolerate.

“They hid behind a California statute called the Knox-Keene Health Care Service Plan Act of 1975. It’s complicated, but HMOs are basically protected from the misconduct of the entities to whom they delegate care, which would ultimately be the nursing home,” he continued.

“To find a way around that, I filed four lawsuits, each questioning whether the Medicare preemption condition on which they were relying actually applied. I established two court of appeals opinions that it did not,” Balisok explained. “Six years after establishing in the state supreme court that the Medicare Act did not preempt a lawsuit, Congress enacted a different Medicare law. So I went at it again.”

After working his way through the courts, Balisok received published opinions from the California Courts of Appeal that established his claim that his clients should be allowed to sue HMOs who used Medicare funds to pay for nursing home care.

“The two cases I referred to basically established that one can sue an HMO for the misconduct of those it delegates care to. State laws and regulations that might serve to protect HMOs no longer apply,” he said.

“That’s how I got started,” Balisok explained. “Because I started early and because I learned just what to do for the Elder Justice Act and how to avoid some other limitations that apply under state law, I became quite a celebrity in certain circles. People kept inviting me to put on programs and explain things to them. I took an interest in the development of the law. There are several state supreme court opinions and court of appeals opinions in this area that I worked on and helped with.

“I managed to make a living doing that. Most people don’t, but there are others much more successful than I. I don’t advertise. I’m happy with my little career of picking and choosing the cases and the issues I want to litigate.”

How big a problem is elder abuse in America?

“There’s neglect of elders in others’ care and custody. There’s physical abuse not requiring care or custody. And there is financial abuse, which includes doing something that would impair the interest of an elder and a piece of real or personal property,” Balisok explained. “Those three things are huge throughout the country, but financial abuse particularly. ‘Impairing the interest of an elder and a piece of real or personal property’ is quite common.”

Some of the cases on Balisok’s docket now are ugly but unfortunately typical of those he chooses. “A guy goes to a nursing home after a stroke. He has a G tube, a little tube in his stomach. One night he pulls it out. They reinsert it without verifying that it’s actually in his stomach and that the seal that prevents it from leaking into his abdomen is intact. It’s not. It’s leaking all over the place, and it’s what they do then that constitutes elder abuse. They didn’t send him to the hospital. They did not discontinue the feeding. And they didn’t order an X-ray immediately because it was after the X-ray technician’s regular hours. To save a hundred dollars, they waited until the next morning. After the X-ray, they waited another three hours to call an ambulance, and they lied to the paramedics about the cause of the patient’s drop in blood pressure, which was all that fluid in his abdomen and not in his stomach. That slowed the process of assessment and correction by the hospital staff.”

Another case involved a man who suffered a stroke. In the hospital, he had a tracheotomy and was placed on a ventilator. He was sent to an attached skilled nursing facility and suffered a series of events that left him brain-dead. When his wife realized he was brain-dead, wears a diaper, and was still on a ventilator, she knew he didn’t want to live like that. She asked the nursing home to take him off the ventilator and let him die.

“For the next sixty or seventy days, they came up with one excuse after another to keep him alive, just so they could continue to collect for his critical care treatment from Medicare,” Balisok explained. “On the hundredth day, following his discharge from the hospital, when Medicare payments ended, they said, ‘Okay, we’ll disconnect him.’”

Balisok has several other cases, including a few against the biggest and most prestigious hospitals west of the Mississippi.

He’s in his seventies now. His wife of some fifty years, Dorothy, who long ago wrote a letter to the president, would like him to retire, to enjoy his golden years while they are both in good health. But Russell Balisok is not ready.

“I saw a lot of killing in Vietnam,” he said. “Bodies laid end to end, stacked like cordwood after an unsuccessful assault by the NVA. Friends killed in action. I understand that. I don’t understand killing for profit. Taking my wartime experiences and trying to make sense of them in terms of what I see in my professional life has been difficult, because everything that affected me so greatly in Vietnam was, for the most part, the fortunes or misfortunes of war. I saw what I can say was stupidity and should never have happened, but so be it.

“But now we have all this killing going on for profit, and it seems to be okay. Everybody knows it’s going on. And nobody wants to talk about it. Nobody will say anything. Whistle-blowers are few and far between. So that’s kind of what I tell my wife every time she says, ‘Why aren’t you retired? Why are you still doing this? Why don’t you take more profitable cases?’”