While NASA is a civilian agency, until 1986, all of its astronauts were military officers. And until 1977, every one of them was white. This may have been because, in order to sell space exploration to the taxpayers, NASA needed human pilots to glamorize its very expensive projects. That required experienced aviators in top physical shape at the flight controls, and only the military had them. The first military service to fully integrate was the air force, but not until 1950. Thus, when NASA was created in 1958, the most experienced military pilots were all white men. Guy Bluford didn’t much care about any of that when he applied to become an astronaut. He merely wanted to fly in space and to utilize his hard-earned skills in aeronautical engineering. And NASA was the place to do it.

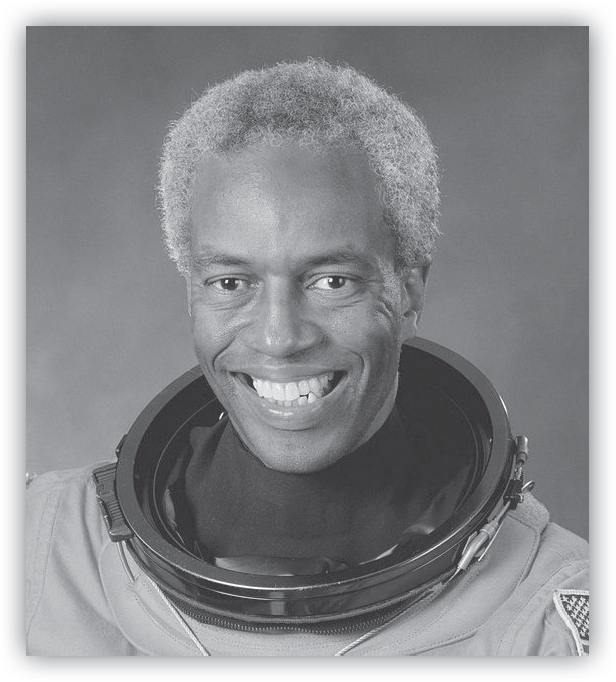

On the night of August 30, 1993, forty-year-old Guion “Guy” Bluford Jr. blasted into orbit aboard the space shuttle Challenger. Less than a minute into the flight, he was fifty thousand feet into the dark sky and subjected to the enormous pull of earth’s gravity as his spacecraft was hammered by the jet stream and shoved to and fro, rattling the shuttle and its crew. Bluford, who had flown 133 combat missions during the Vietnam War, all of them in the F-4 Phantom and almost half of them over North Vietnam, was not at the controls. Instead, he was strapped into a seat on the crew deck with the other mission specialists. This was his first mission into space, but it would not be his last. Even so, Bluford was making history as the first African American in space. He had followed a long, hard, and perilous route to earn this distinction, but that was not on his mind as the Challenger went into earth orbit. His attention that historic night was instead on the mission, as it always was when Bluford was flying or anything else.

Known in his youth as Bunny, Guion Bluford grew up in a middle-class, racially mixed neighborhood in Philadelphia. Both of his parents came from distinguished families. His mother, Lolita, was related to Carol Brice Carey, a well-known contralto and voice coach, and his father was the brother of the editor of the Kansas City Call. Guion Sr. was a mechanical engineer until epilepsy forced him into early retirement. His mother was a special education teacher in public schools. She once confessed she thought Bluford the least likely of her three sons to be successful. She worked overtime to fund college for all three sons. His brother Eugene is a computer programmer and has a doctoral degree. And his other brother, Kenneth, is a teacher by profession, with a PhD in English.

Bluford was fascinated with his father’s attitude toward work. “He would charge out of the house every morning, eager to get to work,” he said. “I thought if engineers enjoy work that much, it must be a good thing to get into.” He decided on a career as an aerospace engineer while he was still in junior high. Yet his indifferent high school grades gave no hint of the prodigious mental capacity he would demonstrate as an adult. After high school he enrolled in Penn State and promptly flunked freshman English, dropping his GPA below 2.0.

He did not give up but pushed himself to work harder. “My best year at Penn State was my senior year, because it took me four years to figure out how to study,” Bluford said. “It was a challenging experience, and I thought, in the end, it gave me a lot of grit. That helped me throughout my career.”

In 1964, he graduated with a BS in aerospace engineering and an ROTC commission as an air force second lieutenant. He went to flight school and earned pilot’s wings in 1965. He was deployed to Vietnam in 1967 as copilot of a high-performance fighter. The F-4C Phantom II is a two-seat, twin-engine, all-weather, long-range supersonic interceptor and fighter-bomber originally developed for the navy. It was later adopted by the marines and the air force, and by the mid-1960s F-4C’s had become a major part of their inventory.

The Phantom is a large aircraft with a top speed greater than Mach 2.2. It can carry more than eighteen thousand pounds of weapons on nine external hardpoints, including air-to-air missiles, air-to-ground missiles, and various bombs. Like other interceptors of its time, the Phantom was designed without an internal cannon. Later models incorporated an M-61 Vulcan rotary cannon. Beginning in 1959, the F-4C set fifteen world records for in-flight performance, including an absolute speed record and an absolute altitude record.

Bluford was stationed at Cam Rahn Bay as a member of the 557th Tactical Fighter Squadron. Most of the missions he flew were to provide air cover for the bombers. They encountered no enemy fighters—most of the North Vietnamese air force had been forced into underground shelters because of the bombing. A few fled to China and were rarely seen. The balance of Bluford’s missions were primarily close air support for infantry.

When he returned from Vietnam, Bluford spent several years as a test pilot and flight instructor. For the next five years, as a T-38 instructor pilot at Sheppard Air Force Base in Wichita Falls, Texas, he taught both American and West German students to fly the sophisticated trainer as part of the air force’s undergraduate pilot training program. This included takeoffs, landings, instrument flying, navigation flying, and formation flying. He served as an assistant flight commander and executive support officer to the deputy director of operations of the 3630th Flying Training Wing. He had more than twelve hundred hours of instructor pilot time in T-38’s and was awarded Luftwaffe wings by the West German Air Force. Many of his German students went on to fly F-104’s while his American students flew various aircraft.

While he was an instructor pilot at Sheppard, Bluford sought several opportunities to become an aerospace engineer within the air force. Unfortunately, the air force was critically short of pilots and needed his skills as an instructor more than as an engineer. The air force also indicated he would need a master’s degree in aerospace engineering if he wanted to serve in that career field. “In preparation for going back to graduate school, I decided to take several advanced mathematics courses by correspondence at the University of California, Berkeley,” Bluford recalled. “I elected to do preparatory course work that way, because there were very few educational opportunities in Wichita Falls. In 1971, I applied to the Air Force Institute of Technology (AFIT) for the master’s program in aerospace engineering. In June 1972, I was accepted into the program and was assigned to AFIT, which is at the Wright-Patterson Base in Dayton. This was the break I needed to get into the engineering field. I was initially assigned to the air weapons program, but I was able to change my major to aerospace engineering. After three semesters, an AFIT professor recommended I stay on for the PhD program.”

Bluford accepted that challenge, and in 1978 he earned a doctorate in aerospace engineering with a minor in laser physics. He ranked consistently among the top 10 percent of his class. While attending classes, he continued to work as a test pilot and a flight instructor at nearby Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. Then he was selected as branch chief of the aerodynamics and airframe branch. “I had completed my research for the PhD program and was in the midst of writing my dissertation. For me, at the time, being branch chief of the aerodynamics and airframe branch was a job I had always wanted. It was a great opportunity for me to use both my technical skills and my flying experience in developing advanced technologies for future aircraft. I led an organization of forty-five to fifty engineers, who were doing basic aerodynamic research in such areas as forward-swept wings, supercritical airfoils, advanced analytical aircraft design techniques, inlets, axisymmetric nozzles, and computational fluid dynamics. It was a great job, and I was really enjoying the work.”

In 1977, the air force told Bluford he needed to return to a flying job. He needed to complete nine years of flying in his first eighteen years of service, but he had so far completed only six years of flying. Bluford began looking for a flying job. His background was primarily in tactical fighters and training aircraft. “I wanted to return to the fighter pilot business by flying F-15 or F-16 aircraft, but the air force wanted me to return as a T-37 instructor pilot,” he recalled. Then Bluford saw that NASA was looking for astronauts to fly the space shuttle, and that opened opportunities for scientists and engineers (mission specialists) to be astronauts. “This looked like a great opportunity for me to fulfill my flying requirements in the air force, utilize my technical skills, and expand my technical knowledge all at the same time,” Bluford said. “I could do it as a NASA astronaut. What a deal! So I applied in 1977. Meanwhile, I was still writing my dissertation with a plan on completing it by the end of 1978.”

He submitted his paperwork for the astronaut program within the air force. Including Bluford, more than a thousand officers applied for both the pilot and mission specialist jobs. The air force selected roughly a hundred officers for consideration, and Bluford was chosen for the mission specialist position.

“I still remember a conversation I had with Tom Stafford, head of the air force selection board, many years later about my astronaut application,” Bluford recalled. “He was impressed with my credentials and thus supported my application to be an astronaut. After the selection process was completed, the air force sent our names to NASA to be included with the applicants from the other services as well as eight thousand civilians. So throughout the summer of 1977, I wondered if I was going to make it or not.”

Bluford survived a series of cuts to become one of thirty-five new astronauts. Among the others were two African Americans and a half dozen women, including Sally K. Ride. As no African American had then ever flown in space, reporters asked Bluford if he felt driven to break the racial barrier and be the first black man to leave earth. He said no, he was not ready to set another goal for himself. He simply wanted to fly in space and keep his personal privacy.

“It might be a bad thing to be first if you stop and think about it,” Bluford said, addressing the mission’s impact on himself rather than the opportunity it provided to speak for his race. “It might be better to be second or third, because then you can enjoy it and disappear, return to the society you came out of, without someone always poking you in the side and saying you were first.”

When Sally Ride learned she would be America’s first woman astronaut, she excitedly called her mother. Bluford was told at the same time that he had been scheduled for the next shuttle flight. He went back to his office and quietly finished some paperwork. He told his wife and their two teenage sons later that night. His two brothers heard the news on the radio the next day.

A few civil rights activists, long critical of NASA for waiting so long to put a black American in space, complained that Ride would precede him in space. That didn’t bother Bluford. Instead, he was delighted. “She can carry the spear and get the attention,” he said. “That relieves me.” Bluford told a reporter he had never perceived his race as an obstacle to anything. “If I had any obstacles, they were self-made,” he said.

Even now, long after his flights into space, Bluford remains something of a loner who says he has no best friends and no heroes. He describes himself as an average guy. “I felt an awesome responsibility, and I took the responsibility very seriously, of being a role model and opening another door to black Americans,” he told the Philadelphia Inquirer. “But the important thing is not that I am black, but that I did a good job as a scientist and an astronaut. There will be black astronauts flying in later missions, and they, too, will be people who excel, not simply who are black who can ably represent their people, their communities, their country.”

Bluford made four flights into space. On his first, aboard Challenger, he was responsible for the in-orbit launch of a communications satellite for the Indian government. He also assisted in a scientific experiment to separate live pancreas cells as part of a long-range biomedical project that NASA hoped would lead to the development of a pharmaceutical industry in space. After five days in orbit, Challenger dropped back to earth and landed at Edwards Air Force Base in the shuttle’s first night landing. Shortly after that, the air force promoted Bluford to colonel.

After months of participating in public relations events for the shuttle program, Bluford returned to Cape Canaveral to begin work in an administrative position. Before he started, however, he was notified of his selection for the next shuttle flight, which included West German aviators. The training for this mission took eighteen months and was conducted in both West Germany and the Houston space center.

Mission STS-61-A, again aboard Challenger, was a Spacelab mission and required a crew of eight. Once in orbit, half the crew worked on a variety of space experiments while the other half slept in a soundproof compartment.

His third shuttle flight’s mission was to study the upper atmosphere, cirrus clouds and the Northern Lights. In 1992, Bluford’s fourth and last shuttle mission had a classified Department of Defense payload. He retired from NASA and the air force the following year.

In 1993, he became vice president and general manager with the engineering and computer software company NYMA Inc., later called Logicon Federal Data Corporation (FDC). It was purchased in 1997 by Northrop Grumman. The company was based in Cleveland, Ohio, and Bluford was responsible for overseeing FDC’s aerospace engineering and research-related programs. Because the company provides support services to NASA as well as the Federal Aviation Administration and the Department of Defense, Bluford is still closely involved with NASA. In 2000, one of his projects was the support of the NASA Fluids and Combustion Facility.

In 2001, Bluford signed with The Space Agency, a public relations firm that represents former astronauts and space pioneers, thus ensuring that Bluford continues to inspire audiences, young and old, when he speaks at seminars, conferences, and corporate meetings. Among his favorite topics is the perspective gained by traveling into space and orbiting the earth. “I’ve come to appreciate the planet we live on,” he told the Philadelphia Inquirer. “It’s a small ball in a large universe. It’s a very fragile ball but also very beautiful. You don’t recognize that until you see it from a little farther off.”

Today, Bluford runs a successful consulting business from a tiny office in suburban Cleveland. His job requires some travel, which gets him around the country.

Not long ago, after speaking at an all-black high school in Camden, New Jersey, Bluford was approached by a shy youngster who mumbled that he wanted to join the air force. Perhaps seeing something of himself decades earlier, Bluford looked at him knowingly, patted him on the shoulder, and said, “Go out there and buck it.”