Health and disease have long been important human concerns. Indeed, preventing disease and prolonging life have formed the basis for the practice of medicine for thousands of years. A major area of interest in human health that has persisted throughout history has been the impact of disease within the context of society. In the modern era, the significance of this relationship is embodied by measures of disease burden within individual communities and countries, as well as globally. Communities that carry a high burden of disease, which entails a high rate of premature mortality, with many people living in poor health, tend to be less economically productive than communities that carry a comparatively low disease burden. As a result, finding ways to control disease is vital in the context of maintaining not only the health of individuals within communities but also the economic productivity and stability of communities and countries.

Public health—which encompasses disease prevention and promotion of physical and mental health, sanitation, personal hygiene, control of infection, and organization of health services—is fundamental in minimizing the impact of disease in society. From the normal human interactions involved in dealing with the many problems of social life, there has emerged a recognition of the importance of community action in the promotion of health and in the prevention and treatment of disease. This is expressed in the concept of public health.

The practice of public health draws heavily on medical science and philosophy, and concentrates especially on manipulating and controlling the environment for the benefit of society. Therefore, it is concerned primarily with housing, water supplies, and food and with ensuring that the necessary resources, including physicians and medicines, are made available to the public. Noxious agents can be introduced into housing and into food and water supplies through farming, fertilizers, inadequate sewage disposal and drainage, construction, defective heating and ventilating systems, machinery, and toxic chemicals. Public health medicine, however, is only one part of the greater enterprise of preserving and improving the health of communities. For example, physicians and therapists cooperate with diverse groups, ranging from architects and builders to sanitary engineers to factory and food inspectors, psychologists and sociologists, chemists, physicists, and toxicologists. Occupational medicine is concerned with the health, safety, and welfare of persons in the workplace. This field may be viewed as a specialized part of public health medicine since its aim is to reduce risks in the work environment.

The venture of preserving, maintaining, and actively promoting public health requires special methods of information-gathering (epidemiology) and corporate arrangements to act upon significant findings and to put them into practice. Statistics collected by epidemiologists attempt to describe and explain the occurrence of disease in a population by correlating factors such as diet, environment, radiation, or cigarette smoking with the incidence and prevalence of disease. The government, through laws and regulations, creates agencies to oversee and formally inspect water supplies, food processing, sewage treatment, drains, air contamination, and pollution. Governments also are concerned with the control of epidemic infections by means of enforced quarantine and isolation—for example, the health control that takes place at seaports and airports in an attempt to assure that infectious diseases are not brought into a country.

Various public health agencies have been established to help control and monitor disease within societies, on both national and international levels. For example, the United Kingdom’s Public Health Act of 1848 established a special public health ministry for England and Wales. In the United States, public health is studied and coordinated on a national level by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Internationally, the World Health Organization (WHO) plays an equivalent role. WHO is especially important in providing assistance for the implementation of organizational and administrative methods of handling problems associated with health and disease in developing countries worldwide. Within these countries, health problems, limitations of resources, education of health personnel, and other factors must be taken into account in designing health service systems.

Advances in science and medicine in developed countries, including the generation of vaccines and antibiotics, have been fundamental in bringing vital aid to countries afflicted by a high burden of disease. Yet, despite the expansion of resources and improvements in the mobilization of these resources to the most severely afflicted areas, the incidence of preventable disease and of neglected tropical disease remains exceptionally high worldwide. Reducing the impact and prevalence of these diseases is a major goal of international public health. The persistence of such diseases in the world, however, serves as an important indication of the difficulties that health organizations and societies continue to confront today.

A review of the historical development of public health, which began in ancient times, emphasizes how various public health concepts have evolved. Historical public health measures included quarantine of leprosy victims in the Middle Ages and efforts to improve sanitation following the 14th-century plague epidemics. Population increases in Europe brought with them increased awareness of infant deaths and a proliferation of hospitals. These developments, in turn, led to the establishment of modern public health agencies and organizations, designed to control disease within communities and to oversee the availability and distribution of medicines.

Most of the world’s primitive people have practiced cleanliness and personal hygiene, often for religious reasons, including, apparently, a wish to be pure in the eyes of their gods. The Old Testament, for example, has many adjurations and prohibitions about clean and unclean living. Religion, law, and custom were inextricably interwoven. For thousands of years primitive societies looked upon epidemics as divine judgments on the wickedness of humankind. The idea that pestilence is due to natural causes, such as climate and physical environment, developed gradually. This great advance in thought took place in Greece during the 5th and 4th centuries BCE and represented the first attempt at a rational, scientific theory of disease causation. The association between malaria and swamps, for example, was established very early (503–403 BCE), even though the reasons for the association were obscure. In the book Airs, Waters, and Places, thought to have been written by Greek physician Hippocrates in the 5th or 4th century BCE, the first systematic attempt was made to set forth a causal relationship between human diseases and the environment. Until the new sciences of bacteriology and immunology emerged well into the 19th century, this book provided a theoretical basis for the comprehension of endemic disease (that persisting in a particular locality) and epidemic disease (that affecting a number of people within a relatively short period).

In terms of disease, the Middle Ages can be regarded as beginning with the plague of 542 and ending with the Black Death (bubonic plague) of 1348. Diseases in epidemic proportions included leprosy, bubonic plague, smallpox, tuberculosis, scabies, erysipelas, anthrax, trachoma, sweating sickness, and dancing mania. The isolation of persons with communicable diseases first arose in response to the spread of leprosy. This disease became a serious problem in the Middle Ages and particularly in the 13th and 14th centuries.

The Black Death reached the shores of southern Europe from the Middle East in 1348 and in three years swept throughout Europe. The chief method of combating plague was to isolate known or suspected cases as well as persons who had been in contact with them. The period of isolation at first was about 14 days and gradually was increased to 40 days. Stirred by the Black Death, public officials created a system of sanitary control to combat contagious diseases, using observation stations, isolation hospitals, and disinfection procedures. Major efforts to improve sanitation included the development of pure water supplies, garbage and sewage disposal, and food inspection. These efforts were especially important in the cities, where people lived in crowded conditions in a rural manner with many animals around their homes.

During the Medieval period and the Renaissance, plague doctors often wore protective clothing like this outfit. The beak mask held spices thought to purify air; the wand was used to avoid touching patients. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

During the Middle Ages a number of first steps in public health were made: attempts to cope with the unsanitary conditions of the cities and, by means of quarantine, to limit the spread of disease; the establishment of hospitals; and provision of medical care and social assistance.

Centuries of technological advance culminated in the 16th and 17th centuries in a number of scientific accomplishments. Educated leaders of the time recognized that the political and economic strength of the state required that the population maintain good health. No national health policies were developed in England or on the Continent, however, because the government lacked the knowledge and administrative machinery to carry out such policies. As a result, public health problems continued to be handled on a local community basis, as they had been in medieval times.

Scientific advances of the 16th and 17th centuries laid the foundations of anatomy and physiology. Observation and classification made possible the more precise recognition of diseases. The idea that microscopic organisms might cause communicable diseases had begun to take shape.

Among the early pioneers in public health medicine was John Graunt, who in 1662 published a book of statistics, which had been compiled by parish and municipal councils, that gave numbers for deaths and sometimes suggested their causes. Inevitably the numbers were inaccurate but a start was made in epidemiology.

Nineteenth-century movements to improve sanitation occurred simultaneously in several European countries and were built upon foundations laid in the period between 1750 and 1830. From about 1750 the population of Europe increased rapidly, and with this increase came a heightened awareness of the large numbers of infant deaths and of the unsavoury conditions in prisons and in mental institutions.

This period also witnessed the beginning and the rapid growth of hospitals. Hospitals founded in the United Kingdom, as the result of voluntary efforts by private citizens, helped to create a pattern that was to become familiar in public health services. First, a social evil is recognized and studies are undertaken through individual initiative. These efforts mold public opinion and attract governmental attention. Finally, such agitation leads to governmental action.

This era was also characterized by efforts to educate people in health matters. In 1852 British physician Sir John Pringle published a book that discussed ventilation in barracks and the provision of latrines. Two years earlier he had written about jail fever (now thought to be typhus), and again he emphasized the same needs as well as personal hygiene. In 1754 James Lind, who had worked as a surgeon in the British Navy, published a treatise on scurvy, a disease caused by a lack of vitamin C.

As the Industrial Revolution developed, the health and welfare of the workers deteriorated. In England, where the Industrial Revolution and its bad effects on health were first experienced, there arose in the 19th century a movement toward sanitary reform that finally led to the establishment of public health institutions. Between 1801 and 1841 the population of London doubled, while that of Leeds nearly tripled. With such growth there also came rising death rates. Between 1831 and 1844 the death rate per thousand increased in Birmingham from 14.6 to 27.2; in Bristol, from 16.9 to 31; and in Liverpool, from 21 to 34.8. These figures were the result of an increase in the urban population that far exceeded available housing and of the subsequent development of conditions that led to widespread disease and poor health.

Around the beginning of the 19th century humanitarians and philanthropists in England worked to educate the population and the government on problems associated with population growth, poverty, and epidemics. In 1798 English economist and demographer Thomas Malthus wrote about population growth, its dependence on food supply, and the control of breeding by contraceptive methods. The utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham propounded the idea of the greatest good of the greatest number as a yardstick against which the morality of certain actions might be judged. British physician Thomas Southwood Smith founded the Health of Towns Association in 1839, and by 1848 he served as a member of the new government department, then called the General Board of Health. He published reports on quarantine, cholera, yellow fever, and the benefits of sanitary improvements.

The Poor Law Commission, created in 1834, explored problems of community health and suggested means for solving them. Its report, in 1838, argued that “the expenditures necessary to the adoption and maintenance of measures of prevention would ultimately amount to less than the cost of the disease now constantly engendered.” Sanitary surveys proved that a relationship exists between communicable disease and filth in the environment, and it was said that safeguarding public health is the province of the engineer rather than of the physician.

The Public Health Act of 1848 established a General Board of Health to furnish guidance and aid in sanitary matters to local authorities, whose earlier efforts had been impeded by lack of a central authority. The board had authority to establish local boards of health and to investigate sanitary conditions in particular districts. Since this time several public health acts have been passed to regulate sewage and refuse disposal, the housing of animals, the water supply, prevention and control of disease, registration and inspection of private nursing homes and hospitals, the notification of births, and the provision of maternity and child welfare services.

Advances in public health in England had a strong influence in the United States, where one of the basic problems, as in England, was the need to create effective administrative mechanisms for the supervision and regulation of community health. In America recurrent epidemics of yellow fever, cholera, smallpox, typhoid, and typhus made the need for effective public health administration a matter of urgency. The so-called Shattuck report, published in 1850 by the Massachusetts Sanitary Commission, reviewed the serious health problems and grossly unsatisfactory living conditions in Boston. Its recommendations included an outline for a sound public health organization based on a state health department and local boards of health in each town. In New York City (in 1866) such an organization was created for the first time in the United States.

Nineteenth-century developments in Germany and France pointed the way for future public health action. France was preeminent in the areas of political and social theory. As a result the public health movement in France was deeply influenced by a spirit of public reform. The French contributed significantly to the application of scientific methods for the identification, treatment, and control of communicable disease.

Although many public health trends in Germany resembled those of England and France, the absence of a centralized government until after the Franco-German War did cause significant differences. After the end of that war and the formation of the Second Reich, a centralized public health unit was formed. Another development was the emergence of hygiene as an experimental laboratory science. In 1865 the creation at Munich of the first chair in experimental hygiene signaled the entrance of science into the field of public health.

There were other advances. The use of statistical analysis in handling health problems emerged. The forerunner of the U.S. Public Health Service came into being, in 1798, with the establishment of the Marine Hospital Service. Almost one hundred years later, the service enforced port quarantine for the first time. (Port quarantine was the isolation of a ship at port for a limited period to allow time for the manifestation of disease.)

The work of an Italian bacteriologist, Agostino Bassi, with silkworm infections early in the 19th century prepared the way for the later demonstration that specific organisms cause a number of diseases. Some questions, however, were still unanswered. These included problems related to variations in transmissibility of organisms and in susceptibility of individuals to disease. Light was thrown on these questions by discoveries of human and animal carriers of infectious diseases.

In the last decades of the 19th century French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur, German scientists Ferdinand Julius Cohn and Robert Koch, and others developed methods for isolating and characterizing bacteria. During this period, English surgeon Joseph Lister developed concepts of antiseptic surgery, and English physician Ronald Ross identified the mosquito as the carrier of malaria. In addition, a French epidemiologist, Paul-Louis Simond, provided evidence that plague is primarily a disease of rats spread by rat fleas, and two Americans, Walter Reed and James Carroll, demonstrated that yellow fever is caused by a filterable virus carried by mosquitoes. Thus, modern public health and preventive medicine owe much to the early medical entomologists and bacteriologists. A further debt is owed bacteriology because of its offshoot, immunology.

In 1881 Pasteur established the principle of protective vaccines and thus stimulated an interest in the mechanisms of immunity. The development of microbiology and immunology had immense consequences for community health. In the 19th century the efforts of health departments to control contagious disease consisted in attempts to improve environmental conditions. As bacteriologists identified the microorganisms that cause specific diseases, progress was made toward the rational control of specific infectious diseases.

In the United States the diagnostic bacteriologic laboratory was developed—a practical application of the theory of bacteriology, which evolved largely in Europe. These laboratories, established in many cities to protect and improve the health of the community, were a practical outgrowth of the study of microorganisms, just as the establishment of health departments was an outgrowth of an earlier movement toward sanitary reform. And just as the health department was the administrative mechanism for dealing with community health problems, the public health laboratory was the tool for the implementation of the public health program. Evidence of the effectiveness of this new phase of public health may be seen in statistics of immunization against diphtheria—in New York City the mortality rate due to diphtheria fell from 785 per 100,000 in 1894 to 1.1 per 100,000 in 1940.

While improvements in environmental sanitation during the first decade of the 20th century were valuable in dealing with some problems, they were of only limited usefulness in solving the many health problems found among the poor. In the slums of England and the United States, malnutrition, venereal disease, alcoholism, and other diseases were widespread. Nineteenth-century economic liberalism held that increased production of goods would eventually bring an end to scarcity, poverty, and suffering. By the turn of the century, it seemed clear that deliberate and positive intervention by reform-minded groups, including the state, also would be necessary. For this reason many physicians, clergymen, social workers, public-spirited citizens, and government officials promoted social action. Organized efforts were undertaken to prevent tuberculosis, lessen occupational hazards, and improve children’s health.

The first half of the 20th century saw further advances in community health care, particularly in the welfare of mothers and children and the health of schoolchildren, the emergence of the public health nurse, and the development of voluntary health agencies, health education programs, and occupational health programs.

In the second half of the 19th century two significant attempts were made to provide medical care for large populations. One was by Russia, and took the form of a system of medical services in rural districts. After the Communist Revolution, this was expanded to include complete government-supported medical and public health services for everyone. Similar programs have since been adopted by a number of European and Asian countries. The other attempt was prepayment for medical care, a form of social insurance first adopted toward the close of the 19th century in Germany, where prepayment for medical care had long been familiar. A number of other European countries adopted similar insurance programs.

In the United Kingdom, a royal-commission examination of the Poor Law in 1909 led to a proposal for a unified state medical service. This service was the forerunner of the 1946 National Health Service Act, which represented an attempt by a modern industrialized country to provide services to all people.

In recent years prenatal care has made a substantial contribution to preventive medicine, for it is hoped that through the education of mothers the physical and psychological health of families may be influenced and passed on to succeeding generations. Prenatal care provides the opportunity to educate the mother in personal hygiene, diet, exercise, the damaging effects of smoking, the careful use of alcohol, and the dangers of drug abuse.

Public health interests also have turned to disorders such as cancer, cardiac disease, thrombosis, lung disease, and arthritis, among others. There is increasing evidence that several of these disorders are caused by factors in the environment. For example, there now exists a clear association between cigarette smoking and the eventual onset of certain lung and cardiovascular diseases. Theoretically, these disorders are preventable if the environment can be altered. Health education, particularly aimed at disease prevention, is of great importance and is a responsibility of national and local government agencies as well as voluntary bodies. Life expectancy has increased in almost every country that had taken steps toward reducing the incidence of preventable disease.

Since ancient times, the spread of epidemic disease demonstrated the need for international cooperation for health protection. Early efforts toward international control of disease appeared in national quarantines in Europe and the Middle East. The first formal international health conference, held in Paris in 1851, was followed by a series of similar conferences aimed at drafting international quarantine regulations. A permanent health organization, the International Office of Public Health (L’Office International d’Hygiène Publique), was established in Paris in 1909 to receive notification of serious communicable diseases from participating countries, to transmit this information to the member countries, and to study and develop sanitary conventions and quarantine regulations on shipping and train travel. This organization was ultimately absorbed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1948.

In the Americas, the organization of international health probably began with a regional health conference in Rio de Janeiro in 1887. From 1889 onward there were several conferences of American countries, which led ultimately to the establishment of the Pan American Sanitary Bureau. This was made a regional office of WHO in 1949, when it became known as the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).

The rise and decline of health organizations has been influenced by wars and their aftermaths. After World War I, a Health Section of the League of Nations was established (1923) and functioned until World War II. After the war, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was set up. It processed displaced persons in such a way as to prevent the spread of disease. It was responsible for the planning steps that led to the establishment of WHO as a special agency of the United Nations (UN).

WHO (also known as the Organisation Mondiale de la Santé) was established to further international cooperation for improved health conditions. Although it inherited specific tasks relating to epidemic control, quarantine measures, and drug standardization from the Health Organization of the League of Nations and the International Office of Public Health, WHO was given a broad mandate under its constitution to promote the attainment of “the highest possible level of health” by all peoples. WHO defines health positively as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Each year WHO celebrates its date of establishment, April 7, 1948, as World Health Day.

With administrative headquarters in Geneva, WHO operates through three principal organs: the World Health Assembly, which meets annually as the general policy-making body; an Executive Board of health specialists elected for three-year terms by the assembly; and a Secretariat, which consists of approximately 8,000 experts, staff, and field workers, who have appointments at the central headquarters or at one of the six regional WHO offices or other offices located in countries around the world. The organization is led by a director general nominated by the Executive Board and appointed by the World Health Assembly. The director general is supported by a deputy director general and multiple assistant directors general, each of which specializes in a specific area within the WHO framework, such as family and community health or health security. The organization is financed primarily from annual contributions made by member governments on the basis of relative ability to pay. In addition, after 1951 WHO was allocated substantial resources from the expanded technical-assistance program of the UN.

The work of WHO is outlined in a six-point agenda, aimed at

1. promoting health and socioeconomic development

2. defending against outbreaks of disease through improving health security

3. reducing poverty by strengthening health services

4. generating health information that can be disseminated to the public

5. collaborating and encouraging partnerships between international, nonprofit, and privately run organizations

6. reforming and improving the organization’s own performance and that of its associated branches and centres

The work encompassed by the six-point agenda spreads across a number of health-related areas. For example, WHO has established a codified set of international sanitary regulations designed to standardize quarantine measures without interfering unnecessarily with trade and air travel across national boundaries. WHO also keeps member countries informed of the latest developments in cancer research, drug development, disease prevention, control of drug addiction, vaccine use, and health hazards of chemicals and other substances.

WHO sponsors measures for the control of epidemic and endemic disease by promoting mass campaigns involving nationwide vaccination programs, instruction in the use of antibiotics and insecticides, the improvement of laboratory and clinical facilities for early diagnosis and prevention, assistance in providing pure-water supplies and sanitation systems, and health education for people living in rural communities. These campaigns have had some success against AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and a variety of other diseases. In May 1980 smallpox was globally eradicated, a feat due largely to the efforts of WHO.

WHO encourages the strengthening and expansion of the public health administrations of member countries. The organization, on request, provides technical advice to governments in the preparation of long-term national health plans, sends out international teams of experts to conduct field surveys and demonstration projects, helps set up local health centres, and offers aid in the development of national training institutions for medical and nursing personnel. Through various education support programs, WHO is able to provide fellowship awards for doctors, public-health administrators, nurses, sanitary inspectors, researchers, and laboratory technicians. WHO also maintains close relationships with other UN agencies, particularly the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and with international labour organizations.

The first director-general of WHO was Canadian physician Brock Chisholm, who served from 1948 to 1953. Later directors-general of WHO included physician and former prime minister of Norway Gro Harlem Brundtland (1998–2003), South Korean epidemiologist and public health expert Lee Jong-Wook (2003–06), and Chinese civil servant Margaret Chan (2007–).

The PAHO, formerly known as the Pan American Sanitary Bureau (PASB) and Pan American Sanitary Organization (PASO), was founded in December 1902 to improve health conditions in North and South America. The organization, which is headquartered in Washington, D.C., is the oldest international health agency in the world and was the first international organization to promote health research and education.

The PASB was organized in response to a yellow fever outbreak that had spread from Latin America to the United States. In 1947 the bureau was renamed the Pan American Sanitary Organization. The name Pan American Sanitary Bureau was retained for PASO’s executive committee. In 1949 PASO was integrated into the UN system as the regional office for WHO. The organization’s name was changed again in 1958 to Pan American Health Organization.

PAHO works in cooperation with both governmental and nongovernmental organizations to coordinate international health activities in the Western Hemisphere. It has been credited with eradicating smallpox and polio from the Americas, achieving progress in the fight against measles, improving life expectancy and infant mortality rates, reducing health gaps between the rich and poor, developing a protocol to protect blood supplies, and improving water safety. PAHO emphasizes equity and improved living standards for impoverished communities.

The organization is led by a four-person executive management team and establishes policies through its governing bodies, the Pan American Sanitary Conference, the Directing Council, and the Executive Committee. Scientific experts are stationed in the group’s offices throughout the hemisphere. The organization’s members include the 35 countries of the Americas, along with Puerto Rico, which is an associate member. France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom are participating states, and Portugal and Spain are observer states.

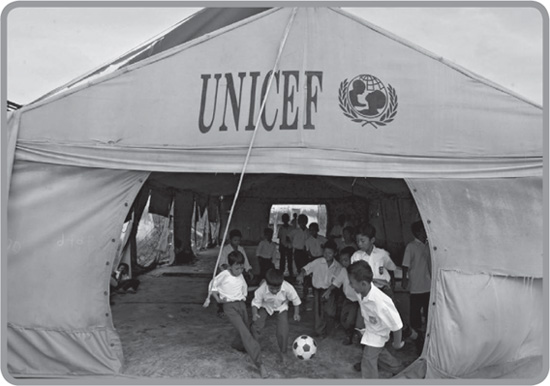

Elementary school students playing football (soccer) at a UNICEF “tent school” in Banda Aceh, Indon., 2005. Dimas Ardian/Getty Images

UNICEF, formerly (1946–53) the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, is a special program of the UN that is devoted to aiding national efforts to improve the health, nutrition, education, and general welfare of children. UNICEF was created in 1946 to provide relief to children in countries devastated by World War II. After 1950 the fund directed its efforts toward general programs for the improvement of children’s welfare, particularly in less-developed countries and in various emergency situations. The organization’s broader mission was reflected in the name it adopted in 1953, the United Nations Children’s Fund. UNICEF was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1965. It is headquartered in New York City.

UNICEF has concentrated much of its effort in areas in which relatively small expenditures can have a significant impact on the lives of the most disadvantaged children, such as the prevention and treatment of disease. In keeping with this strategy, UNICEF supports immunization programs for childhood diseases and programs to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS. It also provides funding for health services, educational facilities, and other welfare services. Since 1996 UNICEF programs have been guided by the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), which affirms the right of all children to “the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health and to facilities for the treatment of illness and rehabilitation of health.” UNICEF’s activities are financed by both government and private contributions.

Representing UNICEF, Jordan’s Queen Rania (centre) visited with schoolchildren in Muzaffarabad, Pak., after an earthquake devastated the region in October 2005. Asif Hassan—AFP/Getty Images

From its inception in 1946, UNICEF focused its aid on maternal and child health services and the control of infections, especially in children. Priority has been given to the production of vaccines, the institution of environmental sanitation, the provision of clean water, and the training of local personnel in their own countries (especially in rural areas). Aid is channeled through organized health services in developing countries. Recent efforts have concentrated on persuading governments to undertake national surveys to identify the basic needs of their children and to devise appropriate national policies.

Doctors Without Borders, or Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), is an international humanitarian group dedicated to providing medical care to victims of political violence or natural disasters, as well as to those who lack access to such treatment. The group was founded in 1971 by 10 French physicians who were dissatisfied with the neutrality of the Red Cross. The doctors believed they had the right to intervene wherever they saw a need for their assistance, rather than waiting for an invitation from the government, and they also felt they had a duty to speak out about injustice, even though it might offend the host government.

In 1972 Doctors Without Borders conducted its first major relief effort, helping victims of an earthquake in Nicaragua. Other significant missions were undertaken to care for victims of fighting in Lebanon (1976), Afghanistan (1979), and the Russian republic of Chechnya (1995). Doctors Without Borders has continued to work to relieve famine, offer medical care to casualties of war, and deal with the problem of refugees in many countries throughout the world. In 2003 Doctors Without Borders was a founding partner in the organization Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi), which works to create medicines for such diseases as malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS.

Doctors Without Borders works in more than 70 countries. Headquartered in Brussels, the organization has offices in some 20 countries. It was an integral part of the emergency relief efforts in Haiti after the earthquake of 2010, though all three of the organization’s hospitals in that country had been destroyed by the quake.

In addition to providing medical assistance, Doctors Without Borders has a reputation as a highly politicized group, particularly skillful in achieving publicity for its efforts. Its vocal opposition to perceived injustice led to its expulsion from several countries. Despite this, the group was awarded the 1999 Nobel Prize for Peace.