Most countries have their own mechanisms for monitoring health and disease and for providing public health services in their communities. However, between developed and developing countries there exist significant differences concerning the availability and administration of health services. Although the factors used to define developed versus less-developed countries are based primarily on economy, with the former typically defined as being highly industrialized and having a high degree of economic output and the latter defined as having low industrial and economic production, these divisions can provide important information about the overall health of a country’s people. In general, because developed countries are able to invest more resources in health maintenance and disease prevention than are developing countries, they tend to experience relatively low disease burdens and to have highly organized and complex health systems. In contrast, because some developing countries lack health systems or have weak public health infrastructure, they tend to be afflicted by high levels of disease burden and rely more heavily on international organizations for aid.

Methods of health administration vary from country to country. Major health functions are frequently grouped in a department that is responsible for health and for related functions. In the United Kingdom these activities are carried out by the Department of Health and Social Security. In the United States the Department of Health and Human Services controls the programs covered by national legislation.

Few central departments of health are all-embracing, and other departments may also operate medical programs of some sort. No country places the health services of its military forces under the central health agency. Because unity of control at the centre is impracticable, coordination is important. Central administration is further complicated in federal systems. In the United States there are 50 states, no two of which have the same patterns of health organization.

The official responsible for the administration of national health affairs is in most cases a member of the Cabinet. Advisory councils are frequently used to bring the ideas of leading scientists, health experts, and community leaders to bear on major national health problems. An organization that provides basic community health services under the direction of a medical officer is called a local health unit. It is usually governed by a local authority. Its programs may include maternal and child health, communicable-disease control, environmental sanitation, maintenance of records for statistical purposes, health education of the public, public health nursing, medical care, and, often, school health services. The local health unit can provide the administrative framework for a wider range of community health services, including the care of the aged, of the physically handicapped, and of the chronically ill and mental health services. Although social welfare services may be provided by a separate agency, there are advantages in amalgamating health and welfare services, because a family’s health and social problems tend to be interrelated.

The population served by a local health unit may be only a few thousand or several hundred thousand. There are substantially different problems involved in administering health services for a large rural area that is sparsely populated and a municipality with a population of one or two million. One problem for local health services is the question of whether they should be run by independent local authorities or be organized regionally to ensure coordination and effective referral and to avoid duplication of services.

Medical care is provided as a public service to some degree in most countries. It may be limited to the hospitalization of persons afflicted with certain ailments—for example, mental disease, tuberculosis, chronic illness, and acute infections. Comprehensive health services may be provided for some specific population groups, as in Canada and the United States, where the federal government provides care for Indians and Eskimos. Many countries have compulsory medical insurance, and some combine the socialization of hospitals with medical insurance covering general medical care, as in Denmark. Full-scale socialization of health services exists in a few countries, including the United Kingdom and New Zealand. Such socialized health services are often alternatively described as systems of public, or universal, health care.

In countries such as the Netherlands and the United States, where voluntary and nonprofit organizations support a considerable share of the health services and operate most of the general hospitals, there is pluralism in health administration. This makes coordination difficult, but voluntary effort has the advantages of involving citizens directly in the development of health services and of promoting experimentation in administration.

There is a trend toward regional planning of comprehensive health services for defined populations. In an idealized plan, the first level of contact between the population and the system, which can be called primary care, is provided by health personnel who work in community health centres and who reach beyond the health centres into the communities and homes with preventive, promotive, and educational services. At the next level of care, specialists in community hospitals provide secondary care for patients referred from the primary-care centres. Finally, tertiary, or superspecialty, care is provided by a major medical centre. The various levels of this regional scheme are linked by a two-way flow of medical records, patients, and health personnel. Regionalization has been most fully achieved in Europe and least so in North America, where voluntary hospitals provide most of the short-term general services and retain autonomy in their administration.

Among the developed countries, there is substantial variation in the organization and administration of health services. The United Kingdom, for example, has a National Health Service with substantial autonomy given to local government for implementation. The United States has a pluralistic approach to health services, in which local, state, and national governments have varying areas of responsibility, with the private sector playing a prominent role.

During the first half of the 20th century in the United Kingdom, the emphasis shifted gradually from environmental toward personal public health. A succession of statutes, of which the Maternity and Child Welfare Act (1918) was probably the most important, placed responsibility for most of the work on county governments. National health insurance (1911) gave benefits to 16 million workers and marked the beginning of a process upon which the National Health Service Act (1946) was built.

The National Health Service Act provided comprehensive coverage for most of the health services, including hospitals, general practice, and public health. The service remained at the periphery, however, in three types of care: (1) Primary medical care is given by family physicians or general practitioners. This service is organized locally by an executive council. Each general practitioner is responsible for providing primary care to a group of people on a particular registry. (2) Specialist consultation and outpatient and inpatient treatment are provided in hospitals under the direction of regional authorities. A later concept makes each district general hospital responsible for providing hospital services for a defined population. (3) Services, such as health visiting, home nursing, home helps, domiciliary midwifery, the prevention of illness, and the provision of health centres are the responsibility of local authorities.

In the former Soviet Union the protection and promotion of public health was the responsibility of the state. There was free public access to all forms of medical care. The principles of the health services were complete integration of curative and preventive services, medicine as a social service, preventive programs, health centres or polyclinics (clinics in which a variety of diseases were handled), and community participation.

The public health services for the Soviet Union were directed by the Ministry of Health. Each of 15 republics of the union had its own ministry. Each republic was divided into oblasti (provinces), which in turn were divided into rayony (municipalities) and finally into uchastoki (districts). Each subdivision had its own health department accountable to the next highest division.

There were well-established referral procedures, from the polyclinics and smaller hospitals in the uchastoki to the larger rayon hospitals, and from feldshers (paramedical personnel trained in medical care) and other paramedical personnel to internists and pediatricians and, when necessary, to more highly specialized personnel.

The health services of the United States can be considered at three levels: local, state, and federal. Locally in cities or counties, there is substantial autonomy within broad guidelines developed by the state. The size and scope of local programs vary, but some of their functions are control of communicable diseases; clinics for mothers and children, particularly for certain preventive and diagnostic services; public health nursing services; environmental health services; health education; vital statistics; community health centres, hospitals, and other medical care facilities; community health planning and coordination.

At the state level, a department of health is charged with overall responsibility for health, though a number of agencies may actually be involved. The state department of health usually has five functions: public health and preventive programs; medical and custodial care such as the operation of hospitals for mental illness; expansion and improvement of hospitals, medical facilities, and health centres; licensure for health purposes of individuals, agencies, and enterprises serving the public; and financial and technical assistance to local governments for conducting health programs.

At the federal, or national, level, the Public Health Service of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is the principal health agency, but several other departments have health interests and responsibilities. Federal health agencies accept responsibility for improving state and local services, for controlling interstate health hazards, and for working with other countries on international health matters. The federal government also has the following specific responsibilities: (1) protecting the United States from communicable diseases from abroad; (2) providing for the medical needs of military personnel, veterans, merchant seamen, and American Indians; (3) protecting consumers against impure or misbranded foods, drugs, and cosmetics; and (4) regulating production of biological products, such as vaccines. In addition, the federal government promotes and supports medical research, health services, and educational programs throughout the country.

Voluntary effort is a significant part of health work in the United States. There are more than 100,000 voluntary agencies in the health field functioning mostly at the local level but also at state and national levels. Supported largely through private sources, these agencies contribute to programs related to education, research, and health services.

Medical care is provided and paid for through many channels, including public institutions, such as municipal, county, state, and federal health centres, hospitals, and medical care programs, and through private hospitals and private practitioners working either alone or, increasingly, in groups. Generally, medical care is financed by public funds, voluntary health insurance, or personal payment.

Thus, in the United States there is great variety in the content, scope, and quality of health services. These services are provided by several independent agencies. In effect, however, they constitute a working partnership for the protection and promotion of human health.

National health organizations fulfill vital roles in ensuring that medical services are made available to the public. These agencies often are also involved in overseeing certain aspects of the social welfare of a country’s population. Between countries, these organizations vary in their overall structure and hence achieve their goals in different ways. Of all the national health organizations in the world, those in place in the United States and the United Kingdom serve as useful models for understanding the infrastructure of these agencies and the diverse tasks that they perform.

The HHS is an executive division of the U.S. federal government that is responsible for carrying out government programs and policies relating to human health, welfare, and income security. Established in 1980 when responsibility for education was removed from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, it consists of several agencies including the Administration for Children and Families, the Administration on Aging, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Indian Health Service, the National Institutes of Health, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The U.S. Public Health Service, part of HHS, is headed by the surgeon general. This individual, often described as “America’s Doctor,” is responsible for communicating scientific and medical information to the public to aid in disease prevention and environmental health awareness and to encourage healthy lifestyle choices.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is an agency of the United States government that conducts and supports biomedical research into the causes, cure, and prevention of disease. The NIH is an agency of the Public Health Service of the HHS. It is the largest single supporter of biomedical research in the country and also provides training for health researchers and disseminates medical information.

The NIH comprises 25 specialized institutes that conduct or support research in various fields of health and disease, including the National Cancer Institute, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Eye Institute, National Institute on Aging, and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

In addition to its various institutes, the NIH maintains the National Library of Medicine, which is the foremost source of medical information in the United States. The NIH also maintains several general research centres and the Division of Computer Research and Technology, which uses computer technologies to support health research programs nationwide. Most of the research funded by the NIH is conducted in medical schools, universities, and other nonfederal institutions. The primary form of funding is the research grant.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is an agency of the HHS that is headquartered in Atlanta. Its mission is centred on preventing and controlling disease and promoting environmental health and health education in the United States. Part of the Public Health Service, it was founded in 1946 as the Communicable Disease Center to fight malaria and other contagious diseases. As its scope widened to polio, smallpox, and disease surveillance, the name was changed to the Center for Disease Control and later pluralized. Today, it subsumes health statistics, infectious diseases, and environmental health; a National Immunization Program; and an Office on Smoking and Health. It consolidates disease-control data, health promotion, and public health programs, and it provides grants for studies and programs, health information to health care professionals and the public, and publications on epidemiology. It is among the world’s foremost epidemiological centres.

The American Medical Association (AMA) is an organization of American physicians, the objective of which is “to promote the science and art of medicine and the betterment of public health.” It was founded in Philadelphia in 1847 by 250 delegates representing more than 40 medical societies and 28 colleges. The AMA includes 54 state or other medical associations. At the turn of the 21st century it had about 300,000 members, or roughly half of all practicing physicians in the United States. Its headquarters are in Chicago.

The AMA disseminates health and scientific information to its members and to the public and carries out a broad range of health education programs via the mass media and lectures. It keeps its members informed of significant medical and health legislation, and it represents its profession before the U.S. Congress and other governmental bodies and agencies, advocating its own views in the process. It helps set standards for medical schools and internship programs, and it tries to detect and alert the public to both quack medical remedies and medical charlatans.

In the AMA headquarters office are various departments concerned with a wide variety of medical topics, including geriatrics, maternal and child care, hospital facilities, medical education, nutrition, drugs, insurance plans, scientific exhibits, health in rural areas, mental health, the cost of medical care, the health of industrial workers, and medical publications. Much of the work of the AMA is carried out under the guidance of committees and scientific councils, which collect and analyze data concerning new medical discoveries and therapies. Such bodies include the council on medical education and hospitals (created in 1904), the council on drugs (founded in 1905 as the council on pharmacy and chemistry), the bureau of investigation (which investigates suspected quackery and charlatanry; founded in 1906), the chemical laboratory (1906), and the bureau of health education (1910). Publications of the AMA include the weeklies Journal of the American Medical Association and American Medical News, and nine journals issued monthly and devoted to such medical specialties as internal medicine, psychiatry, and diseases of children.

The National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom is a comprehensive public-health service under government administration. The NHS was established by the National Health Service Act of 1946 and subsequent legislation. Virtually the entire population is covered, and health services are free except for certain minor charges.

The services provided are administered in three separate groups: general practitioner and dental services, hospital and specialist services, and local health authority services. General practitioners or family physicians give primary medical care to a group of persons who register with them. These doctors and dentists operate their own practices but are paid by the government on a per capita basis (i.e., according to the number of people registered with them). Their services are organized locally by an executive council. Physicians are free to contract in or out of the service and may have private patients while within the scheme. Hospital and specialist services are provided by professionals on government salaries working in government-owned hospitals and other facilities that are under the direction of regional authorities called hospital boards. Local health authority services provide maternity and child welfare, posthospital care, home nursing, immunization, ambulance service, and various other preventive and educational services. They may also operate family-planning clinics, as well as day nurseries for children.

The NHS is financed primarily by general taxes, with smaller contributions coming from local taxes, payroll contributions, and patient fees. The service has managed to provide generally high levels of health care while keeping costs relatively low, but the system has come under increasing financial strain because the growth of medical technology has tended to make hospital stays progressively more expensive.

Developing countries have sometimes been influenced in their approaches to health care problems by the developed countries that have had a role in their history. For example, the countries in Africa and Asia that were once colonies of the United Kingdom have educational programs and health care systems that reflect British patterns, though there have been adaptations to local needs. Similar effects may be observed in countries influenced by France, the Netherlands, and Belgium.

However, whereas clear patterns in health care organization can be found among some developing countries, there also exist wide variations and gaps in the health resources and administration found in other developing countries. These variations and gaps are more pronounced in less-developed versus developed regions because, within the former, complex factors (such as political or societal instability) are capable of complicating and sometimes even entirely disrupting the administration of health care. Countries with such unstable health care infrastructure often are dependent on aid from international organizations.

Despite variations from country to country, a common, if somewhat idealized, administrative pattern may be drawn for developing countries. All health services, except for a small amount of private practice, are under a ministry of health, in which there are about five bureaus, or departments—hospital services, health services, education and training, personnel, and research and planning. Hospital and health services are distributed throughout the country. At the periphery of the system are dispensaries, or health outposts, often manned by one or two persons with limited training. The dispensaries are often of limited effectiveness and are upgraded to full health centres when possible. Health centres and their activities are the foundation of the system. Health centres are usually staffed by auxiliaries who have four to 10 years of basic education plus one to four years of technical training. The staff may include a midwife, an auxiliary nurse, a sanitarian, and a medical assistant. The assistants, trained in the diagnosis and treatment of sickness, refer to a physician the problems that are beyond their own competence. Together, these auxiliaries provide comprehensive care for a population of 10,000 to 25,000. Several health centres together with a district hospital serve a district of about 100,000 to 200,000 people. All health services are under the responsibility of the district medical officer, who, assisted by other professional and auxiliary personnel, integrates the health efforts into a comprehensive program.

Of central importance is the distribution of responsibilities between auxiliaries and professionals. The auxiliaries, by handling the large number of relatively simple problems, allow the professionals to look after only the more complex problems, to supervise and teach the auxiliaries, and to plan and manage the programs.

The district hospital is dependent on a regional hospital, to which patients with complex problems can be referred for more specialized services. Administrative direction of both regional health services and regional hospital services can be combined at this level under a regional medical officer. The central administration of the ministry of health provides policies and guidance for an entire health service and, in some instances, also provides a central planning unit.

Problems of transportation and communication over great distances, shortages of staff and other resources, and inadequacies in staff preparation and motivation often lead to malfunctions in the system. Nonetheless, the public health services developed in African and Asian countries have generally provided a sound basis for future development within the framework of national development.

The organization of public health services in Latin-American countries differs substantially from those of Africa and Asia. These differences are an expression of the different historical backgrounds of the regions. The Latin-American countries are generally more affluent than those of Asia and Africa. Private practice is more widespread, and private or voluntary agencies are more prominent. Health services are provided largely by local and national governments. Many Latin-American countries also have systems of clinics and hospitals for workers financed by employers and workers. The distribution of health services, with health centres, hospitals, and preventive services, is roughly similar to Africa and Asia. The Latin-American countries, however, have used auxiliaries less than African and Asian countries. Latin America has pioneered in the development of health-planning methods. Chile has one of the most advanced approaches to health planning in the world.

Thailand was never colonized and therefore has no historical influence favouring any particular pattern of health services. The Thai Ministry of Health has a well-developed system of hospitals and health centres across the country to serve both rural and urban people. In 2001 the country adopted a universal health care plan, supported in large part by government financing and supplemented by private funds. Within the public health services of Thailand, there are a number of separate divisions—e.g., for tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases, and nutrition.

The difficulties of providing health services for the people of the developing countries involve a cluster of interrelated problems. These arise from the nature of the diseases and hazards to health, insufficient and maldistributed resources, the design of health service systems, and the education of health personnel in those systems. Woven through the health programs of the developing countries and complicating them at both family and national levels are the pressures associated with rapidly growing populations.

There are differences not only in the kinds of diseases of different countries but also in the rates at which they occur and in the age groups involved. Life expectancy in some countries is less than half that in others, principally because of high death rates among small children in the developing countries. In the 1960s across much of Southeast Asia, for example, child mortality was exceptionally high, with some 200 in every 1,000 children expected to die by age five. By 2003, however, due to significant progress in public health, this rate had dropped to 80 in 1,000. Similar trends have been observed in other regions of the world. For example, in Latin America, 153 in every 1,000 children died by age five in the 1960s, but by 2002 this number had dropped to 34 in 1,000. Still, these rates remain much higher than those found in developed countries. In 2007 estimates of under-five child mortality rates in the United States and the United Kingdom were 7.6 and 5.8 per 1,000, respectively.

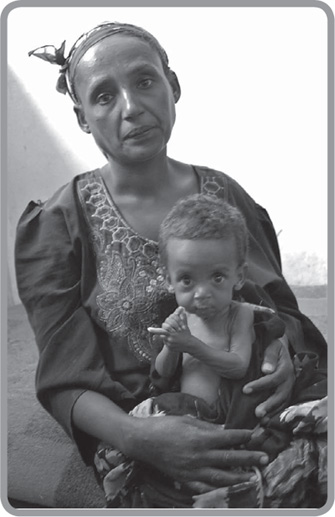

Here, a malnourished Ethiopian child and his mother sit at a feeding center in 2009. The Ethiopian government announced that because of failed crops, more than six million people were at risk of starvation. AFP/Getty Images

The principal causes of sickness and death among small children in the developing world are diarrhea, respiratory infections, and malnutrition, all of which are intimately related to culture, custom, and economic status. Malnutrition may result from food customs when taboos and simple oversight lead to deprivation of children. Gastroenteritis (inflammation of the lining of the stomach and intestines, usually with accompanying diarrhea) and respiratory infections are often due to infectious organisms, some of which may be resistant to antimicrobial drugs. The interrelationships of these diseases increase the complexity of treating them. Malnutrition is often the underlying culprit. Not only does it cause damage itself, such as retardation of physical and mental development, but it also seems to set the stage for other illnesses. A malnourished child develops gastroenteritis, inability to eat, further weakness, and then dehydration. The weakened child is susceptible to a lethal infection, such as pneumonia. Or, to complete the vicious circle, infection can affect protein metabolism in ways that contribute to malnutrition.

Another factor that contributes to this is family size. Malnutrition, with associated death and disability, occurs most often in children born into large and poorly spaced families. The resulting high death rate among small children often reinforces the tendency of parents to have more children. People are not inclined to limit the size of their families until it is apparent that their children have a reasonable chance of survival. Thus, there is a fertility–mortality cycle in which high fertility, reflected in large numbers of small children crowded into a poor home, leads to high childhood mortality, which, in turn, encourages high fertility. This is the basis of the belief that population-control programs should include effective means of reducing unnecessary deaths among children.

Among limitations of resources, shortages of trained personnel are among the most important. Ratios of population to physicians, nurses, and beds provide an indication of the seriousness of these deficiencies and also of the great differences from country to country. Thus, the proportion of population to physicians in developing countries varies drastically. Money is a crucial factor in health care—it determines how many health personnel can be trained, how many can be maintained in the field, and the resources that they will have to work with when they are there. Governmental expenditures on health care vary greatly from country to country.

In an attempt to provide health care for its people, a country must have adequate resources in place to deal with urgent and complex problems, such as obstetric and surgical emergencies for which hospital care is essential. At the same time, however, it must also actively reach into communities and homes to find those who need care but do not seek it and must discover the causes of such diseases as malnutrition and gastroenteritis.

In the education of health personnel, a particular set of problems emerges. Educational programs for auxiliaries are suited to the local situation, perhaps because they were not established in the more developed countries. Medical and nursing education, on the other hand, is similar to that of the more advanced countries, and it prepares students better for working in industrialized countries than in their own. This misfit between education and the jobs to be done has probably contributed substantially both to the ineffectiveness of health service systems and to the migration of professional personnel to the more developed countries.