Charles Darwin

1809–82

Few ideas in the history of science have so completely altered the way we see ourselves as Charles Darwin’s (1809–82) theory that all life, including humans, evolved into its present form through a process of natural selection.

IN THE CENTURY BEFORE DARWIN WAS BORN, scientific observation and the powerful rationality of the Age of Enlightenment were slowly changing the way people looked at the natural world. It was no longer considered quite so mysterious and magical, but something to be catalogued, studied and probed with help from the growing body of scientific knowledge.

Throughout the latter part of the eighteenth century, botanists had built on Linnaeus’s work, discovering and classifying more and more species of plants around the world. To a lesser extent, zoologists had done the same thing with animals. Great new botanical gardens, such as Kew in London, and zoological gardens were the living testament to the efforts of these species hunters.

Both scientists and theologians began to ask just how all these species had come about, and why each seemed so perfectly suited to the environment in which it lived – fish for swimming in the sea, birds for flying in the sky, and so on.

The orthodox view was that of the Creationists. According to the book of Genesis in the Bible, ‘God created every living creature that moves … every winged fowl … and every thing that creeps on the face of the Earth’. So the Creationists believed, as many still do, that every species was created at once by God – and that each was perfectly designed by him suit the conditions in which it lived. In 1802, the theologian William Paley argued in favour of this original design idea with an example: if you found a watch in the desert, you would surely assume it had been made by some skilled watchmaker. How much more skilled, then, was the watchmaker who fashioned the human eye?

However, some thinkers were beginning to question the idea that all species have been there from the start, unchanging. More and more naturalists were looking at fossils and finding they were of species that often seemed very different from those alive today. Where had those species gone, and why were there so few fossils of creatures that are alive today?

At the same time, geologists such as James Hutton were beginning to challenge the orthodox idea that the world was just a few thousand years old, and that all the landscapes were created in a series of brief catastrophes. A growing minority were arguing that the Earth is in fact very old, and that landscapes were created by long slow cycles of erosion and upheaval.

Against this background, more and more thinkers began to argue that species are not fixed but have actually changed, or evolved, through time. One of these thinkers was Charles Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus Darwin. Another, and perhaps the most famous, was the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck.

Lamarck not only developed a picture of how species progressed in a purposeful manner from a single-celled organism to the supreme species, mankind, but also suggested just how this evolution takes place. He argued that each species has an ‘inner feeling’ which propels it to ascend the ladder of evolution. He also argued that skills which aid survival can be passed on to the next generation and so gradually built up. A giraffe that stretched its neck to reach higher branches, for instance, would pass on its long neck to its offspring.

Lamarck’s ideas so shocked those with orthodox religious views that those championing them were often vilified and sacked from teaching positions – even as late as 1840. Many scientists, too, found the idea of inheriting acquired characteristics unconvincing. And Lamarck’s system hardly began to explain how each species is so marvellously adapted to its environment.

Darwin’s great breakthrough was not the discovery of evolution – Lamarck and others had done that. What he did was work out what exactly evolution is and how it happens. His insight was to focus on individuals, not species, and he showed how individuals evolve by natural selection. Natural variation within a group of individuals means that some will be better equipped to survive in particular conditions, and if they survive they will pass their characteristics on to their offspring. Later commentators have characterized his idea as ‘survival of the fittest’, but it was never a phrase Darwin himself used. This mechanism explained how all species, including humans, evolved to become well suited to their environment.

Young Darwin

Darwin was born on 12 February 1809 in Shrewsbury, the son of a well-to-do country doctor. Charles was the youngest of the family and the only boy, and throughout his childhood he was doted on by his sisters. He was educated at the local public school, but was too busy collecting nature specimens and conducting chemistry experiments to shine in class. ‘The school,’ Darwin said, ‘as a means of education to me was simply a blank.’

At the age of 16 he went off to Edinburgh to study medicine like his father. But Darwin found all the operations far too gruesome and spent much of his time with the zoologist Robert Grant, a great believer in Lamarck’s ideas. Both were avid collectors and spent many a day rambling in the Scottish hills looking for plants.

Since he was clearly not suited for the study of medicine, Darwin’s father sent him off to Cambridge to study divinity at Christ’s College. Here again, Darwin was distracted by another naturalist – this time the Reverend Professor John Henslow, who had energetically restored Cambridge’s botanical gardens after years of neglect. As with Grant, the two of them formed a firm bond and would often go specimen hunting together.

The trip of a lifetime

In 1830, Henslow was offered the post of botanist on HMS Beagle, soon due to set sail to South America on a surveying trip for the Admiralty. Henslow was unable to go, but offered the job to young Darwin instead. At first his father refused permission, but he relented after strenuous efforts from his daughters.

The Beagle voyage was to be, quite literally, the trip of a lifetime for Darwin (see here). Initially meant to take two years, it actually lasted over five. By the time Darwin came back, he was a changed man. Not only had he gathered enough data about species around the world to last him a lifetime, but he had learned enough by close observation of the extraordinary range of wildlife he saw to start sowing the seeds of his theory of evolution. Nonetheless, Darwin was never a hasty man, and it took him many years of patient thought and study before his theory was ready for publication.

Fame and marriage

In the meantime, he found himself quite a celebrity when he returned to London, for Henslow had been giving lectures based on the specimens and notes Darwin had sent back whilst sailing round the world. He was appointed a fellow of the Geological Society, invited to join the exclusive gentleman’s club, the Athenaeum, and elected to a fellowship of the Royal Society. Yet he was never one to seek the limelight, and over the next few years he spent much of his time quietly making notes to develop his ideas on the species question, building up data, visiting zoos, talking to plant breeders, naturalists, birders and anyone who might give him some more background information.

Although he loved the quiet, studious life, he also began to feel the need for companionship, and in 1838 the 29-year-old Darwin decided to marry his cousin Emma, having carefully weighed the pros and cons. It proved to be a very happy marriage, and the couple soon moved to Down House near Bromley in Kent and remained there for the rest of their lives. Darwin was never in robust health – and may have caught some tropical disease on the Beagle voyage – but he was well looked after at Down House by Emma, and continued building up his ideas on evolution.

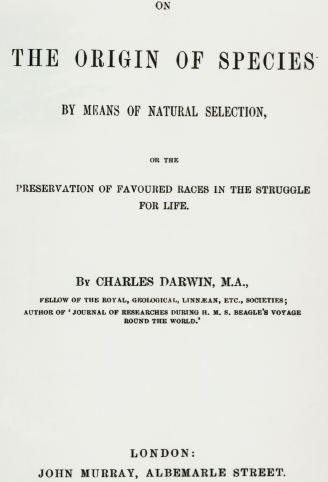

The title page of Darwin’s Origin of Species. Published in 1859, the first print run was sold on the first day; the controversy it generated, however, would last far longer.

The breakthrough

Although Darwin’s ideas mostly grew by slow accumulation, there was one ‘Eureka!’ moment, when he read An Essay on the Principle of Population by Thomas Malthus. In this essay, written in 1798, Malthus had argued that populations – both human and animal – will always multiply until they exceed the amount of food available, at which point the population will crash, only for the process to start again. Darwin was excited: ‘It at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result would be the formation of new species…. I had at last got a theory by which to work.’

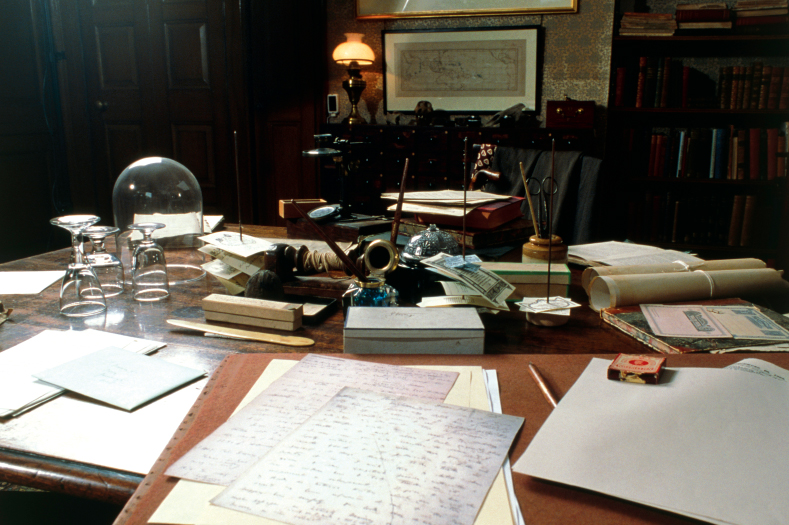

Darwin’s desk at Down House, the country retreat where he moved in 1838, and where he would spend the rest of his life, insulated from the storms his work would arouse.

Yet though he had his theory, he kept it very much to himself. Indeed, he soon embarked on ten years’ work, writing a treatise on a single species of barnacle, which he described thus: ‘Mr Arthrobalanus [is] an enormous coiled penis.’ He might have carried on in this way if a bombshell had not dropped suddenly on his desk in the summer of 1858.

The rival

The bombshell was a letter from Alfred Wallace, a young naturalist then lying ill with malaria in the Molucca Islands in Indonesia. Wallace outlined a theory of evolution by natural selection which corresponded almost exactly to Darwin’s own. ‘I never saw a more remarkable coincidence,’ Darwin later commented. Darwin talked to his friends – the famous geologist Charles Lyell, the botanist Joseph Hooker and the philosopher T.H. Huxley – and together they arranged for Darwin’s and Wallace’s ideas to be presented together, making it clear that Darwin had developed his ideas 12 years previously.

Spurred into action, Darwin then wrote his great book On the Origin of Species, in which he outlined his ideas and gave a wealth of supporting evidence gathered from the Beagle voyage and subsequent research. It was a sensation, and the first edition of 1,250 copies sold out on the day of publication, 24 November 1859.

The great debate

Some people immediately embraced the idea, seeing how it explained a huge amount about the natural world. Others condemned it as an affront to God, because nowhere did Darwin’s ideas leave room for the biblical Creation. Heated discussions began to take place around dining tables and in debating chambers across England.

The most famous encounter was between Darwin’s friend T.H. Huxley and the Bishop of Oxford, ‘Soapy’ Sam Wilberforce. At one point in the debate, Wilberforce challenged Huxley to say whether it was on his grandfather’s side or his grandmother’s that he was descended from an ape. But this cheap jibe cost Wilberforce victory. Turning it neatly round, Huxley argued persuasively and seriously enough to carry the day. This was the picture across the country, and the Darwinists, as they came to be called, gradually won more and more people to their cause.

A major setback occurred in 1862, when the Scottish physicist William Thomson, later Lord Kelvin, estimated the age of the Earth scientifically. Kelvin declared the Earth could be no older than 40 million years, and possibly only 20 million years. His calculation was based on how long it would have taken the Earth’s interior to cool down to its current temperature from its original molten state. This was a real blow, because Darwin’s theory depended on the Earth being much older. But it turned out that Kelvin was mistaken about how fast the Earth is cooling; further calculations showed that the world is over 4 billion years old.

Human descent

In the meantime, Darwin, who kept quietly out of the debate down in Down House, wrote The Descent of Man (1871), in which he explained how his theory of evolution applied to the evolution of mankind from the apes. In a famous passage, Darwin wrote, ‘Man with all his noble qualities … still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origin.’

Darwin went on developing his ideas, particularly in relation to humans, for the rest of his life. In 1872, at the age of 63, he published an important book on how emotions and expressions might have evolved, entitled Origin, the Expression of the Emotions in Man and the Animals.

By now, the long years of poor health and hard study were taking their toll. He died on 19 April 1882 aged 73 and was widely mourned. He was buried with honour in Wesminster Abbey, his coffin carried by, amongst others, his friend and champion T.H. Huxley.

A Galapagos finch, one of the birds which helped inspire Darwin’s theory of evolution.

The voyage of the Beagle

In his autobiography, Darwin wrote, ‘The voyage of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life and has determined my whole career.’ When Darwin embarked on the voyage, he was simply an amateur botanist with only a basic knowledge of plants, very little zoology and no geology. As Darwin set sail, Henslow gave him a copy of the first volume of Charles Lyell’s newly published book Principles of Geology. It was a revelation to him, showing how landscapes had evolved gradually through long cycles of erosion and upheaval. At the Beagle’s first stop in the Cape Verde islands, Darwin saw a seam of white coral running up the side of the volcano, showing that it had gradually been uplifted from the sea, not suddenly as the Catastrophists said. It was enough to convince him that Lyell’s ideas were right, and he wrote home, ‘Geology carries the day.’

As the voyage continued down the east coast of South America, Darwin gathered a huge number of specimens and took copious notes on the wildlife and geological features that he encountered. With everything he saw, the idea that species are designed and fixed once and for all seemed increasingly unlikely to him. The culmination of his observations came in the Galapagos Islands off the west coast of South America in autumn 1835. There are twenty or so islands here and each one, Darwin noted, had its own subspecies of finch with its beak perfectly adapted to its way of feeding.

Some used their beaks to crack nuts, others to suck nectar from flowers, and so on. As Darwin said, ‘One might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends.’ It was for him the clinching piece of evidence that species evolved to suit their environment; they were not ‘designed’ to suit it right from the start.

By the time Darwin came home, he was firmly convinced of the reality of evolution. All he needed to do was to work out how and why it happened. That was his lifetime’s work.