JANUARY 1926: WASHINGTON, DC

It seemed like a typical winter day when Maris Boggs, a small woman wrapped in a big fur coat, walked briskly to the bus stop near the corner of Twelfth and F Streets in Washington, DC, just under a mile from the White House. But Maris was about to discover it was anything but.

Although it was a little after noon, the sun was hidden behind dark clouds, making it feel more like dusk. The fierce wind was unrelenting, saturated with a bitter icy rain. The bus held the promise of warmth and coziness, but it had not yet arrived.

Maris noticed a candy shop with a covered doorway, and she took shelter there, hoping to stay warm and dry from the razor-sharp wind and sleet. While she was waiting anxiously for the bus, she suddenly felt something brush up against her ankle. Startled, Maris peered down through her glasses and saw a shivering puppy with bedraggled white fur, brown ears, and two little brown patches on his back.

He looked up at her pleadingly with his brown-green eyes and tried to wag his tail, but he was too cold. Maris reached down and petted him. The puppy leaned in closer to her, snuggling into her soft fur coat and enjoying the warmth from the touch of her small hand.

“Why, you poor thing!” Maris said. “You must be nearly dead.”

Looking around, Maris wondered if the puppy’s owner might be in the candy shop. She opened the door, and the puppy dashed inside with Maris following closely behind him. They were immediately enveloped by the warmth of the shop, and by the sweet, heavenly scents of sugar, chocolate, vanilla, licorice, and mint.

She asked the storekeeper and customers if they knew who the puppy belonged to, but no one knew anything. Realizing the puppy was either lost or abandoned, Maris picked him up and held him in the crux of her arm. She had a dilemma.

Maris couldn’t keep the puppy, but she also knew if she left him, he would die from the cold. The solution proved to be simple. She would just have to take the puppy with her to work and keep him until she found his owner or a new home.

Luckily, she was the boss, so no one in the office was likely to complain about the puppy this one time. Maris, who had recently celebrated her thirty-seventh birthday, was the cofounder and director of the Bureau of Commercial Economics, a nonprofit organization founded in 1913.

Maris’s mission in life was to spread goodwill throughout the world. She was a globe-trotting world traveler who hobnobbed with political leaders and diplomats. Maris believed that if people learned about other cultures, they would have a better understanding of one another. As a result, Maris felt people would get along better and create world peace.

Her organization promoted goodwill by showing educational movies about different cultures and countries to millions of people all over the world, free of charge. This was an innovative idea, and in the beginning, some people were unsupportive. At the time, showing movies in movie theaters had only been around for about twenty years, and back then, going to the movies was looked down on as a lowly form of entertainment.

But Maris didn’t listen to the naysayers. She spread goodwill with eight “traveling motion picture theaters,” which were specially equipped trucks that transported a movie projector, a phonograph, a generator, a movie screen, and an assortment of silent black-and-white films. These trucks traveled all over the United States and were loaded onto ships and sent to continents as far away as Asia, Africa, and South America. And if the trucks couldn’t travel over roads to the more remote villages, she would have the equipment loaded on camels, llamas, or dogsleds — whatever it took to get the job done.

Now Maris had another mission — to find the puppy a good home. So when the bus finally arrived, Maris carried the puppy on board.

The rule for bringing a dog on the bus was strict, even for a quick ten-minute bus ride. The puppy was only allowed on the bus if he sat on Maris’s lap. This kept big hulking dogs like Saint Bernards and Great Danes off the bus. Maris’s puppy looked like a fox terrier, and he was so small he wouldn’t bother anyone. Or so she thought.

The bus was crowded, and Maris found an empty seat by squeezing in between a plump man in an expensive suit who was busy reading a magazine, and a woman who was clutching a large shallow basket on her lap.

As the bus clamored down the busy street, dropping people off and letting others on, the puppy started to squirm. As tired and hungry as he was, the woman’s basket had sparked his curiosity. He needed to know what was inside.

The tiny puppy stretched his scraggy body out across Maris’s lap and unabashedly stuck his wet nose into the basket. He discovered it was full of vegetables. Satisfied, he wagged his stubby tail enthusiastically, knocking into the plump man’s magazine.

The woman holding the basket quickly placed a newspaper over the vegetables, not wanting dog germs contaminating them. The man folded up his magazine in a huff, his concentration broken.

Maris was embarrassed. But before she had a chance to explain his plight to her fellow passengers, the bus came to a halt. It was her stop. She held the puppy protectively in her arms, walked by the scowling bus driver, and exited the bus.

When she arrived at her office with the tired and hungry puppy, she asked her secretary what they should feed him. The secretary rushed to the store and bought some hamburger meat. But when they tried to feed it to him, the puppy didn’t take a bite. He soon fell asleep under Maris’s desk.

Maris worked diligently for the rest of the afternoon. When five o’clock rolled around and it was time to go home, Maris was presented with another problem. No dogs were allowed in her apartment building. But Maris wasn’t going to let this foil her plan.

When she arrived at the grand Beaux-Arts style building she called home in the neighborhood of Mount Pleasant, she avoided the front entrance. Stealthily, she went around to the back of the massive beige-colored brick building. Holding the puppy in one arm, Maris climbed up the fire escape. When she reached her apartment’s window on the top floor, she carefully climbed through it with the puppy.

Once safely inside, the puppy took a good look around his new home. It was posh and spacious with large French doors that opened onto a stone balcony. Maris introduced him to the maid, who took a good look at him.

The puppy was very thin and malnourished, and Maris expressed worry that he hadn’t eaten. Since he refused to eat the hamburger meat, which was something she figured all dogs would gobble up, she didn’t know what to feed him. When her maid suggested dog biscuits, the puppy’s brown ears twitched and his face perked up. He seemed to understand.

Dog biscuits were promptly purchased at the store, and when the puppy was given some, he ate with so much gusto he tried to eat the cardboard box, too. Finally satisfied and with a full stomach, he curled up on the plush carpet and quickly fell into a deep, deep sleep.

Over the next several weeks, Maris realized he was a puppy like no other. His intelligence and natural curiosity were already evident. Whenever anything interested him, he tilted his head to the side and gave it a good sniff. He was also developing an independent streak. He steadfastly refused to respond to snapping fingers or the command “Here, boy!”

As much as Maris loved the puppy, she knew she couldn’t keep him. It wasn’t fair to keep him hidden inside her apartment all day, every day. She wanted him to have an exciting life, one full of adventures befitting such an intelligent and strong-minded dog. But she had no idea who would want a puppy.

Then, one day while she was reading the newspaper, she came across an article on Richard Evelyn Byrd. At thirty-seven years old, the handsome and intrepid aviator was making headlines with his plan to be the first person ever to fly over the North Pole — a daring feat that many considered crazy.

In 1926, aviation was an extremely dangerous profession. People were still trying to figure out the best way to build airplanes, and they were considered somewhat experimental. It was a given that pilots would more than likely get hurt, if not killed, in a crash.

On top of that, flying in the Arctic was extremely hazardous. The Arctic winds could blast a plane off course, navigating in the icy and snowy Arctic fog was nearly impossible, and the subzero temperatures might cause a plane’s engine and parts to fail, causing it to crash.

“The easiest way a man can make a monkey of himself is to take up Arctic exploration work by airplane,” Byrd once said.

Despite this, Byrd had recently wowed the world when he became the first person to fly an airplane in the Arctic over Greenland. But that wasn’t the first time the world took notice of his adventurous spirit.

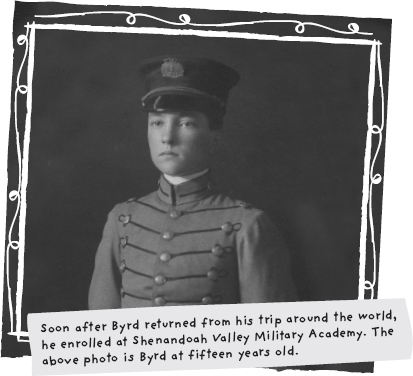

In 1902, when Byrd was a skinny, freckle-nosed fourteen-year-old living in Winchester, Virginia, a family friend invited him for a visit to their new home in the Philippines. Byrd wanted to go in the worst way. He thought this was the perfect opportunity for him to take a trip around the world — all by himself.

When he told his mother his plans, she immediately said no. But Byrd was determined. After some convincing, his mother reluctantly changed her mind.

“Richard was born an adventurer and explorer, absolutely without fear,” his mother said.

He packed his new suitcase with a pair of extra underwear, two neckties, a pocketknife, and a ball of string. His mother insisted on traveling with him from Winchester to Washington, DC, where they said good-bye. Then he boarded a train that took him to San Francisco.

“That day my face was full of poison oak and I could hardly see because my eyes were so swollen,” Byrd said. “My mother was not given to weeping, but she wept that day. I felt more than a little blue myself.”

In San Francisco, he boarded the transport ship Sumner, where Mrs. Wendell, a friend of his uncle’s, traveled with him. After they made it to their first port in Japan, a major typhoon struck, tossing the ship at sea and making everyone sick. But Byrd was having the time of his life.

“I thought that was a wonderful storm,” Byrd said. “I didn’t know enough to be afraid.”

After Byrd arrived in the Philippines, he traveled alone throughout Asia, Europe, and Africa. On his return trip home, the ship got lost, but that didn’t upset Byrd.

“I was tickled to death,” he said. It also ignited Byrd’s interest in navigation.

“I don’t suppose I had ever thought much about navigation before,” Byrd said. “I knew the compass was necessary … but I did not know that time was part of the calculation for determining position. Navigation became at once a mysterious and important function.”

When Byrd finally arrived back in New York more than a year later, he was greeted and interviewed by a dozen newspaper reporters. Everyone wanted to know about his trip around the world.

It was at this time Byrd knew, without a doubt, that he wanted to be an Arctic explorer. And even though he hated cold weather, he hoped to be the first person to set foot on the North Pole.

He read everything he could get his hands on about the Arctic and the explorers. Although Byrd was not a stellar student in school, there were two subjects he excelled in — mathematics and navigation. Byrd knew these two subjects were essential if he wanted to find his way to the North Pole.

But, when he was twenty years old and a student at the U.S. Naval Academy, Byrd’s dream was dashed when polar explorer Robert Peary proclaimed that he was the first person to reach the North Pole.

“The day that Peary discovered the North Pole was the darkest day of my life,” said Byrd.

This wasn’t the only setback to derail his dream.

At the Naval Academy, Byrd was a fierce and reckless athlete. Although he was average in height and very lean, Byrd was really strong and powerful. He loved the rough-and-tumble sport of football, where he went all out as the quarterback. During a showdown with archrival Princeton, Byrd was tackled in a pileup. The crowd in the stands cheered enthusiastically. Byrd had scored a touchdown.

But Byrd was lying on the field, unable to stand up. His foot had been crushed and was broken in three places. His teammates gathered around him and carried him off the field. His football season was over.

Nevertheless, Byrd was just as enthusiastic in gymnastics. His favorite event was the flying rings. During his final year at the Naval Academy, Byrd was determined to help his team win big. So he came up with a daredevil routine that he called “the dislocating.”

Byrd explained that the dislocating routine required swinging “completely head over heels without changing grip, with arms at full length — unbending, forcing my shoulders through a quick jerk that made it look as if they were put out of joint.”

He was certain it was going to dazzle the judges. But they never had a chance to see it. While practicing the dislocating routine in front of a crowd, Byrd swung around and missed catching the rings. He could hear the crowd gasp in horror while they watched him fall thirteen feet to the mat below.

“The crash when I struck echoed from the steel girders far above me, and there was a loud noise of something snapping,” said Byrd.

The loud snapping noise was his foot — the same foot that he broke while playing football.

The routine landed Byrd in the hospital with a dislocated ankle and broken foot. The outside anklebone was broken in half and clicked every time he tried to walk, causing extreme pain. The doctors operated on his foot and wired it back together.

Byrd spent the next five months trying to recover, and from his hospital bed, he studied feverishly, barely squeaking by in his classes. Although he still managed to finish the school year and graduate from the Naval Academy on time, his injured foot would nearly ruin his career.

Byrd began his career in the navy on board the battleship USS Kentucky and was soon transferred to the USS Wyoming. His foot continued to cause excruciating pain, affecting his entire leg, especially when he had to stand for hours at a time while on watch duty.

“Certain kinds of deck duty left me aching all over from the pain that began in the old mangled ankle,” said Byrd.

But the final blow came when Byrd fell down an open gangway and broke his foot for a third time. The doctors nailed the broken bones back together, but Byrd’s foot was never the same. From that day on, he would walk with a slight limp. Soon after, he retired from the navy.

“Career ended,” Byrd wrote. “Trained for a seafaring profession; temperamentally disinclined. A fizzle.”

However, a few months later, in the winter of 1917, the United States entered World War I, and Byrd rejoined the navy. He dreaded being stuck behind a desk doing paperwork, but he had a new plan.

“For several years, I had known my one chance of escape from a life of inaction was to learn to fly,” Byrd said.

He tried to talk the navy into assigning him to the aviation program, but the doctor who examined his foot and leg said no. Byrd couldn’t fly.

“Give me a chance,” Byrd pleaded. “I want to fly. Give me a month of it; and, if I don’t improve to suit you, I’ll do anything you say.”

The doctor reluctantly agreed, giving Byrd a month’s trial.

Byrd was sent to Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida to learn how to fly, which he did with his usual all-out gusto. He crashed his plane twice — once in a head-on collision. Luckily, no one died.

“He used to go up with anyone who even said he could fly. He risked his life more times than any other beginner I ever saw,” said Lawrence Shea, a pilot who taught Byrd.

When Byrd earned his wings, making him a full-fledged navy pilot, his goal was to be a pioneer in the budding field of aviation and to make himself invaluable to the field. At the time, air navigation was a big problem. Pilots navigated using a compass and a map while looking out the window for landmarks. No one dared to fly out of sight of land or over the vast ocean on long flights.

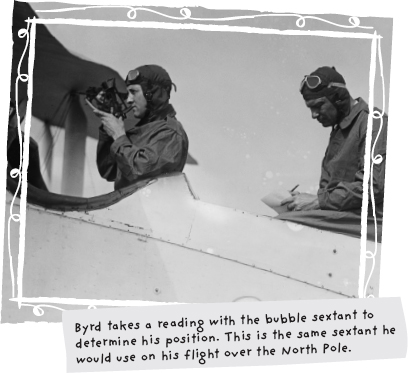

Byrd solved this problem. He developed the “bubble sextant,” an air navigation instrument that indicates the pilot’s position. Instead of having to look for land, the navigator looks through the sextant and locates his position based on the altitudes of the sun or stars. Byrd also invented the “drift indicator,” an instrument that told a navigator how far off course the winds had blown his airplane.

Byrd’s inventions revolutionized air navigation, opening the doors for the possibility of flying airplanes over the ocean and the snow-covered Arctic. And Byrd would be using these inventions on his flight to the North Pole.

When Maris finished reading the newspaper article and seeing the photo of Byrd, she realized that she had met him before. She knew in that instant Byrd would give her puppy an exciting life. She immediately called him and offered him the puppy. But Byrd didn’t want him.

“Don’t you like dogs?” Maris asked.

“Certainly I like them,” Byrd said with a slight southern drawl. “I have had many dogs, and several of them were the most loyal friends I ever had. But they died. And because I had become so deeply attached to them, their deaths always affected me brutally. You can understand that, I think. That is why I don’t want another one.”

Maris wouldn’t give up, “I know you will like him. In fact, if you persist in this dangerous business of flying to the Poles, I daresay he will probably outlive you.”

But Byrd wasn’t convinced.

“I don’t think it would be a good idea to take a dog, and especially a puppy, to the polar regions,” Byrd said. “It’s very cold, you know, and he might freeze to death.”

Maris was dogged in her determination. She wouldn’t take no for an answer. “If a man can stand it, a dog can stand it,” she said.

Byrd didn’t know what to say to that, and he reluctantly agreed to take the puppy.

“You had better rush him to New York,” Byrd said. “Because we are planning to leave in a few days. Our ship is nearly loaded now.”

Maris wasted no time. She found a large wicker basket, put the puppy inside along with two wool sweaters, a dog collar, two leashes, a bar of sweet-smelling soap, a brush, and a comb. She wrote out the address on a piece of paper and attached it to the lid of the basket. It read, “Lieutenant Commander Richard E. Byrd, the North Pole.”

Soon the puppy would be on top of the world.