APRIL 5, 1926: BERTH 10, CLINTON AVE., BROOKLYN NAVY YARD, NEW YORK

Below the rusty and tar-covered decks of the steamship SS Chantier, in the galley where all of the meals were cooked, the puppy whined. A metal chain was attached to his dog collar. He pulled the chain with all his might, trying to break free from it, but it was no use. He couldn’t escape.

After a few more attempts, the puppy realized it was futile, and he changed tactics. He sat down and waited, his brown ears twitching while he listened anxiously for approaching footsteps. Once he heard them, he planned on barking like a rabid, mad dog. Until then, he would just have to sit tight, which is exactly what Byrd and the crew wanted.

Everyone was too busy to be bothered with the puppy, and his ferocious barking didn’t help make him seem friendly or approachable. Truth be told, many on the ship thought the puppy was a pest. Even so, they did take the time to name him. Some called him Frosty. Others called him Dynamite. But the name Igloo stuck.

The chain attached to his collar was there for his own good. No one wanted Igloo to run away or get underfoot. Everyone was busy, trying to get the ship loaded and ready for its departure as quickly as possible.

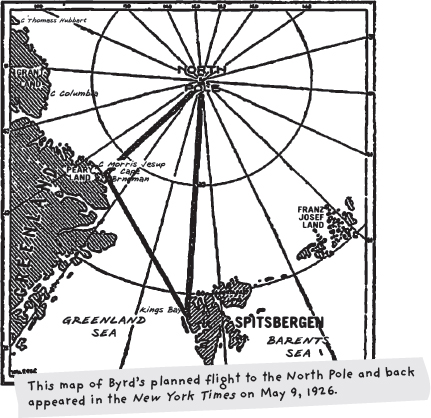

The lanky, good-natured carpenter Charles “Chips” Gould was hammering furiously, trying to insulate the ship’s quarters with sugarcane fiber. The quarters would have to keep the crew warm when they arrived in Spitsbergen, Norway, their starting point for Byrd’s flight to the North Pole. Byrd chose Spitsbergen because its distance to the North Pole was only 720 miles. That was close enough to allow Byrd to fly to the North Pole and back without having to risk landing on the deadly ice to refuel and take off again.

Byrd was in a hurry to start the journey. It would take about a month to reach Spitsbergen from New York. And it was crucial that Byrd reach the North Pole in May when it would still be too cold for thick fog to form. Fog would seriously jeopardize his mission. There also needed to be snow covering the rocky terrain so the plane had a better chance of landing safely when it returned from the North Pole. But Byrd was also in a hurry to get to Spitsbergen before Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen arrived.

Hailed as the “King of All Living Explorers,” Amundsen was the first person to set foot in places where other men died trying. He was the first to find the elusive Northwest Passage and the first in the race to reach the South Pole. Now he had set his sights on being the first to fly over the North Pole, just like Byrd.

This wasn’t Amundsen’s first try. The year before, he and American polar explorer Lincoln Ellsworth and four others tried to fly two planes over the North Pole. They were nearly killed when they lost their way in the fog and one of their planes had mechanical problems, forcing them to crash-land in the floating ice–filled water. Their planes quickly froze over, and walls of ice closed in all around them.

Using the only tools on hand — axes, picks, knives, and an ice anchor — it took them a month to cut one of the planes out of the ice and build an ice bridge across a chasm. By hacking, sawing, and stomping down on the ice over and over again, they were able to build an airstrip of smooth ice. With their emergency rations nearly gone, the starved and exhausted men narrowly escaped with their lives as they miraculously flew one of the planes back to safety.

This time Amundsen wasn’t going to try to fly an airplane over the North Pole. Instead, he was going to fly a dirigible. A dirigible, or blimp, is a lightweight aircraft that can travel long distances without having to land and refuel.

“There isn’t a safe place to land a heavy plane with skis between Cape Mitre and the Pole,” Amundsen said. “If you come down in open water, and there is a lot of it, you haven’t a chance. And if you try to land on the deceptive ice, it means a crash. In any event, motor failure means wreckage of the plane, ninety-nine times out of one hundred. And it’s a long and dangerous walk home, over open leads and rotten ice, for two men without dogs and with limited rations.”

Despite Amundsen’s vast experience and legendary reputation as the “last Viking,” Byrd boldly disagreed with him.

“Our great aim is to show what the airplane can do,” Byrd said. “Secondly, it is to find new land. Thirdly, it is to try to reach the Pole by air.”

Byrd’s choice of airplane was the most important decision in planning the flight. After careful consideration, he decided to fly a trimotor monoplane named the Josephine Ford, which was built by a Dutch aircraft company called Fokker. Byrd knew a plane wasn’t always dependable, but he figured a three-engine plane was the answer to a successful flight over the North Pole. If two engines failed, the plane could still fly with one engine and avoid an emergency landing.

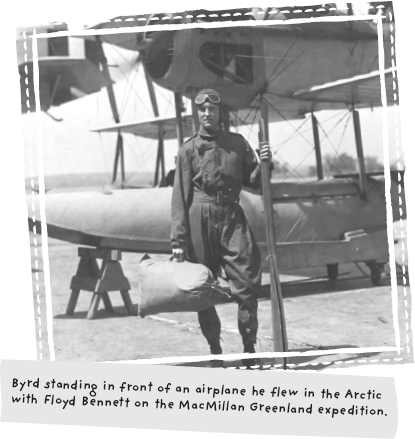

He also chose the calm, cool, and gutsy pilot-mechanic Floyd Bennett to accompany him. They’d become fast friends the year before when they flew 2,500 miles over the Greenland ice cap together, where Byrd was the navigator and Bennett was the pilot.

“He showed that he was a good pilot … fearless and true — one in a million,” Byrd said of Bennett.

Once during a flight on the Greenland expedition, Byrd noticed the oil gauge quickly rising, indicating the oil tank was ready to explode. There was nowhere to land the plane without crashing. It was a do-or-die situation.

Without hesitation, Bennett climbed out onto the plane’s wing. With the Arctic wind blowing and the plane bouncing up and down, Bennett loosened the oil cap, relieving the pressure and saving their lives. The frostbitten Bennett then climbed back into the plane, and they successfully completed their flight.

Byrd and Bennett were a good team, and despite Amundsen’s warning, they were determined to fly over the North Pole in an airplane.

“True, we realized the hazardous nature of the flight,” Byrd said. “Experienced polar travelers told us we were fools. The fog which lies over the Arctic Ocean would add to the already great risks; and, if we came a cropper [crashed], it would take us, they said, at least two years to walk back to land, if we ever made land at all. Nevertheless, these were risks we were prepared to take.”

Byrd was careful in all of his planning, which was evident in the cargo being loaded onto the ship. There were stacks and stacks of wooden crates, trunks, and steel barrels filled with supplies piled high throughout the ship. The food supplies alone contained four hundred pounds of emergency rations of pemmican (a mixture of lean, dried meat, cereal, suet, lard, currants, raisins, and spices that is heated over a stove with water turning it into a mush), 4,500 pounds of whole carcasses of beef, and another eight tons of other food, including eggs, sausage, bacon, oatmeal, dried milk, butter, sugar, cream cheese, and pea soup. There were enough provisions to feed the fifty men who had eagerly volunteered to be the crew aboard the ship for three months.

The two planes Byrd planned to use on the expedition were the trickiest of all the cargo to load onto the Chantier. Byrd watched the men load the Fokker trimotor monoplane and the yellow-and-orange Curtiss single-engine Oriole. The Oriole would be used only as a scouting plane. If the Fokker met with disaster, the scouting plane was not able to travel long distances on rescue missions.

It took a nail-biting six hours to load the sixty-three-foot red wing from the body of the Josephine Ford safely on board. The clanking sound of chains and the rumble of the gears shifting were loud as a crane hoisted the wing up into the air. It hovered over the opened hatch, where the men stood on ladders as they carefully eased it into the hold below deck. But it was too big to fit, and it became stuck.

Everyone was quiet for a brief moment, as if time stood still. The men grabbed some axes and began chopping away the bulkhead that was in the way. Little by little the wing was lowered until it finally fit and was safely secured without a scratch.

While Byrd and his crew got the ship in shape, Igloo wallowed in his misery down in the galley. But it wasn’t all doom and gloom for him. There was one particularly bright spot, the gregarious carrot-topped cook with the wire-rimmed glasses, George “Cook” Tennant.

Cook Tennant tried to cheer up Igloo with some treats. It worked for a bit. He was an excellent cook with plenty of experience feeding hungry mouths. He had sold hot dogs at the World’s Fair in Saint Louis, baked pies for oil riggers in California, and cooked on fishing and sealing ships in Alaska.

But on this day, even Cook Tennant was too busy for Igloo. It was midafternoon, too early for dinner, when Igloo heard footsteps approaching the galley. The footsteps came closer and closer, and Igloo began barking loudly. When Igloo looked up, he saw a stout, dark-haired man looking down at him. Igloo wagged his tail, happy to see him.

It was Igloo’s other new friend, Tom Mulroy. He was the chief engineer of the Chantier, and Mulroy was not put off by Igloo’s wild barking. He was impressed that a puppy’s bark could sound “like a lion’s roar.”

Mulroy unhooked Igloo’s chain, allowing Igloo to trot along beside him as they left the galley. Mulroy often took Igloo for a “walk,” deep into the bowels of the ship to the hot and steamy engine room where Igloo could inspect the pumps, pipes, coils, valves, generators, furnace, and boiler. The ship’s after hold contained the nine hundred tons of coal that would be used to feed the furnace and power the ship for 15,000 miles.

But today Igloo was in for a surprise. Instead of going down to the engine room, Mulroy and Igloo went to the upper deck of the ship.

Igloo walked among the crates, hoses, and equipment on the deck. When Igloo looked up, he saw a flag with an American eagle on it waving in the wind on the ship’s masthead. When he looked to the bow of the ship, Igloo could see Byrd standing tall, wearing his navy-blue dress uniform and waving his hat to 2,000 people lined up on the pier. The crowd was cheering and bidding them farewell.

While the tugboats pushed the freshly painted black-and-red Chantier out of the harbor, the crowd shouted as the other tugs and steamers in the harbor sounded their whistles and sirens. Swept up in the excitement of the moment, Igloo rushed to the side of the deck and barked, joining in with the crowd to cheer.

For the first several days, the sea was rough. Waves rolled the ship back and forth as rain pummeled down. Everyone on board was seasick — except Igloo.

Unleashed, Igloo was having a ball running as fast as he could up and down the stairs between the decks, trying to time it just right as the ship rolled back and forth. When Igloo wanted a change of pace, he went up onto the main deck, and he ran as fast as he could until he reached the end of the ship, where he let out a bark of delight. Then he’d start all over again.

But sometimes his timing was off, and the ship would roll to one side while Igloo was in midsprint, sending him flying across the slippery deck. With his legs flailing, he plunged headfirst toward the mouth of the ocean, only to be caught by the railing of the ship. On these hair-raising occasions, when Igloo cheated death, he would forgo the bark and slink back to his starting point. Then he would do it all over again.

While Igloo was busy making mad dashes around the decks, the square-jawed captain of the Chantier, Michael Brennan, was struggling to steer the ship. It turned out that the weight from the coal in the after hold was too heavy, causing the rear of the Chantier to sink down lower into the ocean. All hands were called on deck. Byrd and his queasy, seasick crew spent days breaking their backs moving the coal from the after hold to the midship coal bunkers. But it didn’t dampen their enthusiasm.

“No one considers seasickness any cause to give up,” said Byrd.

Even though the crew members were busy, several of them caught a glimpse of Igloo zipping by and nearly being swept overboard. They told Byrd about it, and he was concerned. From that moment on, Byrd took Igloo under his wing.

Igloo was delighted by this new arrangement. When Igloo first met Byrd, he had immediately liked him, and had enjoyed the quick, short walks Byrd had taken him on around the deck. During these walks, Igloo noticed that among all of the men on the ship, Byrd was the top dog. Whenever Byrd gave an order, his crew complied.

Igloo immediately moved in to Byrd’s stateroom, bringing along his favorite new toy, a stuffed goat that he enjoyed pouncing on and wrestling with. Despite the upgrade of his sleeping accommodations, one stormy night Igloo couldn’t catch a wink of sleep.

The wind howled ruthlessly and giant waves pounded the ship, violently rocking it back and forth. A table crashed down, and Igloo found himself being tossed among books, papers, and shoes. When there was a sudden moment of calm, Igloo jumped up onto the foot of Byrd’s bed. And in that instance, Igloo knew he belonged by Byrd’s side.

Soon after, Igloo refused to eat in the galley, no matter how hungry he was — unless Cook Tennant pressed him. Then he might have a nibble, but no more. Instead, he gallantly followed Byrd into the dining room and took his place by Byrd’s chair. After everyone had helped themselves, Byrd would fix a plate for Igloo and serve it to him. Igloo ate with relish.

While at sea, Byrd and Bennett spent most of their time planning their flight, not wanting to miss any details. Their main concern was a crash. Sometimes, Igloo sat in on these discussions, preferring to sit on Byrd’s lap.

“We are flying in dangerous country,” Byrd wrote in his diary. “The three hundred miles to Greenland is the most hazardous region in the world to fly over. If we should have a forced landing there we would be swept in to [sic] the Atlantic before we could cover fifty miles and the ice would melt under us.”

If the plane crashed between Peary Land, a mountainous peninsula in northern Greenland, and the North Pole, Byrd and Bennett would have to walk back, dragging a sled with 240 pounds of pemmican. The pemmican would last for sixty days. They would also carry a rifle so they could hunt polar bears and seals for food, and they would bring a tent and an inflatable twelve-pound “donut” boat that was made of hot-air balloon cloth and could carry six hundred pounds of passengers and cargo.

Along with the six-pound first-aid kit, which contained splints and bandages, the Yale-educated Dr. Daniel O’Brien, who was the expedition’s medical officer, also gave Byrd and Bennett instructions on how to perform surgery in case one of them was severely injured in a crash.

Byrd and Bennett were also concerned about the weight of the plane. If the cargo was too heavy, the plane would burn more gasoline, and they might not get to the North Pole and back.

“The weight has to be kept down to a minimum and yet there are so many things we should have to add to our safety,” said Byrd.

Byrd spent time carefully weighing all of the equipment and cargo, but he wouldn’t know exactly how much they could take until they tested out the plane in Spitsbergen.

Sometimes while Byrd was busy planning, Igloo skipped out and explored the ship. One of his favorite stops on board was the radio room. Whenever he found the door to the radio room open, Igloo would sneak in, lie down, and pretend to nap. With his eyes half open, he would watch the sandy-haired Malcolm Hanson busily working out the bugs in the new cutting-edge shortwave radio station.

The radio was a crucial piece of technology for Byrd. His plane would be equipped with a receiver and transmitter, allowing him to receive weather reports and send back progress reports while in flight.

The radio headset Hanson wore fascinated Igloo. One time, it fell to floor, and Igloo went over to investigate. Tilting his head to one side, Igloo listened to the noise coming from it. When Hanson tried to pick it up, Igloo barked three times, letting Hanson know that under no circumstances was he to touch the headset until Igloo was finished studying it. Hanson, who was known to be as smart as a whip, complied.

After twenty-four days at sea, with the help of an ice skipper, whose specialty was navigating ships through the dangerous iceberg-filled waters, the Chantier reached King’s Bay in Spitsbergen, Norway at 4 p.m. on April 29. Byrd was relieved that they had arrived right on time, but the relief was short lived. He quickly realized that despite his hasty departure, he was too late.

Amundsen was already there. And he was almost ready to start his flight to the North Pole. He was just waiting for his dirigible to arrive from Italy.

The two men were in a race to be the first to fly over the North Pole. And, despite all of his careful planning, Byrd had no idea about the kind of trouble that was in store for him.