APRIL 29, 1926: SPITSBERGEN, NORWAY, THE ARCTIC CIRCLE

From the moment the Chantier’s rusty anchor dropped into the icy King’s Bay, trouble was brewing. Igloo stood on the upper deck where he had a bird’s-eye view of the ship and harbor.

He was wearing one of his new wool sweaters at the insistence of his friend Tom Mulroy. At first, Igloo wasn’t sure if he liked wearing it. The sweater felt bulky and cumbersome, and it somehow seemed wrong for any self-respecting dog to have to wear it. But it did fend off the bitter Arctic air that chilled his bones. And all of the men were wrapped up in warm winter clothes, too. So Igloo grudgingly accepted it.

There was a flurry of nonstop action on deck, and Igloo didn’t want to miss out. The trouble for Byrd began when he radioed Amundsen. Byrd politely asked Amundsen to help make arrangements for the Chantier to be moored to the only dock in the harbor. Byrd also offered to help Amundsen in return, if he should need it.

The dock was critical to Byrd’s plan. It was the only place where he could unload his airplanes. If he didn’t have access to the dock, then he would fail before even having a chance to try to fly over the North Pole. In the months before embarking on his long journey, Byrd had cabled ahead to the local manager of the dock and asked if he would be able to secure the Chantier there. Byrd was told that it wouldn’t be a problem. But today it was a different story.

“Greatly disappointed today to hear from Amundsen by radio that we could not go alongside dock,” Byrd wrote in his diary.

The reason was that a dark gray Norwegian gunboat, the Heimdahl, was already moored at the dock and resupplying its store of coal. The crew from the Heimdahl was preparing to assist Amundsen when his dirigible arrived and to help him with any emergency he might experience while in King’s Bay. Trying to find a solution, Byrd asked Captain Tank-Nielsen of the Heimdahl directly if the Chantier would be able to moor there for a few hours, just so Byrd could unload his planes.

The captain said no. The Heimdahl had nearly sunk a few days earlier when drifting ice rammed into the ship. The captain feared if his ship left the safety of the dock, an unexpected shift in the wind would cause more ice to ram into the Heimdahl. The captain wasn’t budging. And Byrd was told it would be days before he would be allowed to use the dock.

Byrd realized it was no use arguing, but he wasn’t about to give up. He had an idea that the rest of his crew thought was crazy. But Byrd was willing to risk it all.

“We may be licked,” Byrd wrote in his diary, “but don’t want to be licked waiting around and doing nothing … All opposed to my decision. They were wise probably.”

It was the time of year in the Arctic when the sun never sets — when the Earth is tilted on its axis, so the Arctic is always facing the sun. And Byrd could easily read the newspaper by sunlight at 3:30 in the morning. Since the days felt like they had no beginning or end, it would allow Byrd’s crew to work through the night without taking a break to sleep. There wasn’t a moment to spare if Byrd’s new plan was going to work.

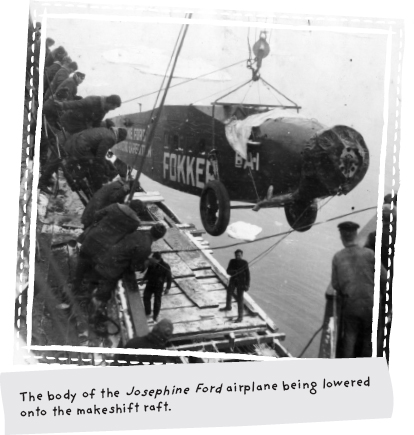

With a hammer in his hand, the hardworking ship’s carpenter, Chips Gould, and the crew got busy. They tied together four lifeboats and hammered wooden planks across them. They worked all night long. The wind felt raw and snow fell steadily, accumulating chilly, thin layers on their backs.

By early morning the makeshift raft was built. The snow was falling harder now and the ice floes were getting thicker in the water. Igloo watched the crane reach down into the hold of the ship and lift a large crate up into the air. The snowflakes whirled around as the crate was lowered onto the deck. When the crate was broken open, Igloo trotted over to investigate. Curious, he tilted his head to the side and sniffed around the body of the Fokker airplane.

Everyone was tense while the airplane was lowered carefully onto the raft and securely tied. Next, Igloo watched the crane lift the wing of the plane into the air. It hung heavily. As it was positioned to be lowered onto the body of the plane, a sudden gust of wind kicked in. The force of the wind slammed the raft into the side of the iron ship.

The men struggled to secure the wing to the deck with ropes and move the raft to the stern of the ship. Suddenly, the ferocious wind pushed a gigantic iceberg toward the ship. The iceberg was about to crash into the ship’s rudder. The crew quickly grabbed some dynamite and threw it at the iceberg, blowing it up into small pieces and saving their ship.

For the next twelve hours, the storm was merciless, and waves and ice thrashed against the ship. Despite the fierce cold, the crew stood guard, fending off runaway ice floes and protecting the raft and wing from blowing away or sinking. When Byrd finally turned in to sleep that night, he got up every hour to check the ice. By morning, the wind finally died down and the ice was floating calmly in the water. Byrd gave the go-ahead to lower the wing onto the raft.

“If anything slips,” Byrd said while the wing was hanging dangerously in the air, “the expedition comes to an end right now.”

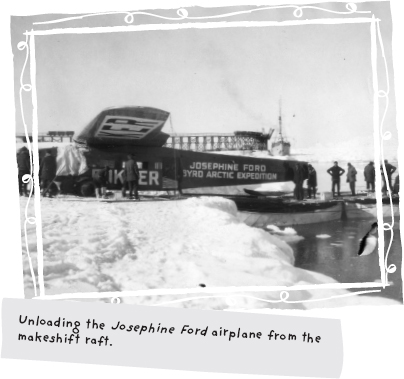

Everyone breathed a sigh of relief when the wing was secured to the fuselage. But now the most difficult part of Byrd’s plan began. The Chantier was anchored about three hundred feet from the shore, and a strong gust of wind or wave could easily topple the raft, sinking them all. To make matters worse, the sharp and jagged ice was so thick and packed together so tightly that it looked like a person could walk right over it all the way to the shore without getting his feet wet. But looks were deceiving.

Luckily, Byrd received some much-needed help from Norwegian Captain Astrup Holm, whose cargo ship the Hobby was being chartered by Amundsen and was nearby. Captain Holm circled the Chantier and cut the ice away from it. He then got into a small boat with Byrd’s ice pilot, Norwegian Isak Isaksen, who had thirty years of experience in the Arctic Ocean. Together, using boat hooks, ice picks, and sheer brute force, they chopped the ice and shoved it out of the way, carving out an opening and exposing the deep black water.

Byrd gave the order to begin rowing the raft through the watery path despite being very worried.

“It was anxiety for my shipmates that made that trip a most anxious one for me,” Byrd said. “I felt entirely responsible for their safety.”

But Igloo was on the raft with Byrd, giving his full support to the endeavor. It was slow going. Many of the men had never rowed a boat before, and one was using his oar backward. The crew struggled to keep the ice from pounding into their fragile raft, using their oars and long poles to push it out of the way. But the poles and oars were of no use when they were more than one hundred yards from the Chantier and two massive icebergs towered over them. They carefully wedged their raft between the icebergs, knowing that they “could have crushed us like nuts in a nutcracker,” Byrd said.

Nevertheless, they made it.

And Byrd wrote in his diary that it was a lot of fun. “Got cheers from Norwegians, which we returned,” he wrote. “Norwegians didn’t think we would make it.”

For the next thirty-six hours, Byrd and his crew worked nonstop. Igloo stuck close by, keeping an eye on their progress.

“If it was a very big undertaking for my men to get the plane ashore,” Byrd said. “It surely was a muscle-tearing job for them to get the plane and equipment up to the top of the long incline through the deep snow.”

The plane had to be assembled and a runway had to be made by digging and smoothing out the snow with shovels. This proved to be the hardest job of all. Since there wasn’t any level ground, they would have to try to take off going downhill.

Cook Tennant set up a tent near the plane and brewed strong hot coffee. The coffee helped keep the crew warm. At times the temperature dipped to fifteen degrees below zero, and everybody’s feet were cold, especially Igloo’s. His wool sweater, now stained with oil, wasn’t always warm enough against the harsh weather, and he shivered.

On these occasions his friend Tom Mulroy would lend him his jacket and place Igloo on a crate. Even so, there were times that Igloo couldn’t stop shivering. Although he was stoic and uncomplaining, Igloo was sent back to the anchored ship where he warmed his paws by the heat of the stove in Cook Tennant’s galley. But as soon as he could feel his paws again, he was eager to get back by Byrd’s side, where he belonged.

While Igloo was busy fending off frostbite and trying to convince a crew member to take him back to the action, the first attempt at a trial flight was made. May 3 was a day of reckoning for Byrd.

“Bennett and I were not half so worried about breaking our necks on the polar ice as we were about smashing our plane on the takeoff,” Byrd said.

If the plane crashed, it could be the end of the expedition.

Byrd and Bennett got into the cockpit of the Fokker. The plane’s motors roared to life and it jetted down the icy runway. Suddenly, there was an ominous silence, and the plane skidded uncontrollably right into a snowdrift.

Hearts sank in disappointment. The plane was damaged. A ski was shattered and the landing gear was mangled. It was a disaster.

“The forward right ski split and fitting torn loose around the fuselage. Very discouraging but we will not get discouraged,” Byrd wrote in his diary.

The plane needed new skis, but there wasn’t any hardwood to be found. Even so, this wasn’t going to stop Byrd and his crew. They would have to make do with what they did have. The carpenter, Chips Gould, and Tom Mulroy took the oars from a lifeboat and worked tirelessly through the next two nights making new skis for the plane.

Byrd also received some unexpected help. Despite Amundsen’s orders that his crew stay away from Byrd, one crew member, a twenty-five-year-old Norwegian named Bernt Balchen came over anyway and introduced himself. The blond, blue-eyed Balchen was a middleweight boxing champion, a champion skier, and held an engineering degree. More important, he had been a pilot in the Royal Norwegian Navy Air Service, and he also had lots of experience flying in cold weather. When he offered to help Byrd, he didn’t know it was the beginning of bigger things to come.

“We’ve used a mixture of paraffin and resin on the runners and found it very effective,” Balchen told Byrd. “You see, about this time of the year, when the snow begins to melt, the friction is greater. If you use this mixture, I don’t think you’ll have so much trouble.”

But even with the new skis, Byrd and Bennett were still having trouble getting the plane to lift off.

“We were having difficulties … in getting off the snow with the lightest possible load. What would happen when we tried our total load of about 10,000 pounds?” Byrd said.

It wasn’t until the third try that Byrd’s plane finally lifted off. He and Bennett flew the plane for two hours in a test run. They were happily surprised there was low gas consumption. This meant there was a good chance they could make a nonstop, round-trip flight to the North Pole and back. They knew firsthand that taking off and landing midroute was too risky.

Still, Byrd couldn’t begin his flight to the North Pole until he received a decent weather report from the meteorologist on the trip, good-natured Bill Haines. Haines, who everyone called “Cyclone,” was always calm, slow, and methodical — unless there was an emergency. Then he moved like a cyclone. His skill as a meteorologist was critical to Byrd’s success. If the weather report was wrong, it could spell disaster for Byrd and Bennett.

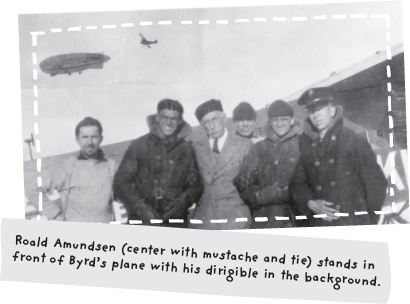

Byrd was still waiting for good weather on the morning of May 7. It was shortly after 10 a.m., and Igloo was standing next to him when they heard the hum of an engine. Igloo looked into the sky. It wasn’t Byrd’s airplane making the noise. It was Amundsen’s dirigible looming overhead. It circled around and lowered itself to the ground by its hangar on the snow-covered hill, right behind Byrd’s runway and two hundred yards from his airplane.

The race to the North Pole was back on, and whatever lead Byrd had was now gone. It was full speed ahead.

On May 8, Cyclone Haines informed Byrd that the weather was finally good for flying. Igloo, who had been keeping an eye on Cook Tennant in the field kitchen, heard the commotion by the plane and scurried over to find out what was happening.

Byrd was carefully checking the navigational instruments while the food and fuel were being loaded onto the plane. The motors — which were covered with canvas hoods that had small openings at the bottoms where a small gasoline stove was placed to heat them — were warmed up and ready to roll.

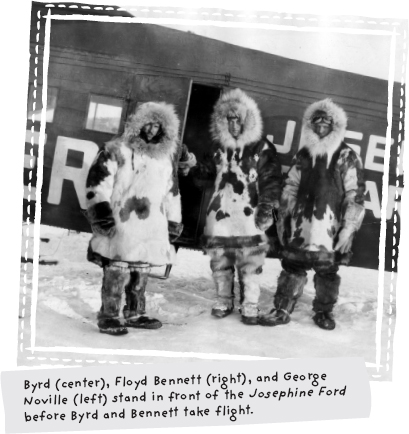

Since there was no heater in the Fokker airplane, and the temperature in the cabin of the plane could easily drop to fifty degrees below zero while flying, Byrd and Bennett were wearing polar-bear-fur pants and hooded reindeer-fur parkas with mittens and boots to ward off frostbite. They would also wear goggles during the flight to prevent snow blindness from the glare of the white snow and ever-present sun.

Igloo stood among the crowd of men from both Byrd and Amundsen’s crew. Everyone had gathered to bid Byrd and Bennett farewell. Igloo watched them board the Fokker airplane, and he waited anxiously for the plane to take off.

The plane zoomed down the runway, bouncing awkwardly over the frozen snowy bumps. As it reached the end of the runway, it was clear that it was too heavy to lift off. Igloo watched in horror as the plane crashed into a snowdrift, nearly flipping over onto its side.

Igloo sprinted, his frozen paws kicking up the snow like dust as he charged to the plane. He was frantic to see if Byrd and Bennett were okay. Igloo felt utter relief when he saw Byrd climb out of the plane.

“So you’re here, fella,” Byrd said to him. “Well, you have just seen something that neither you nor I will forget in a long time.”

Sick with disappointment, Byrd plowed through the deep snow to check the landing gear. His sinking heart soared when he saw that the skis were still in perfect condition.

“I knew that if the landing apparatus would stand the strain,” Byrd said, “we would eventually take off for the Pole with enough fuel to get there.”

But first they had to lighten the load on the plane.

“There is a lot of stuff in that plane that must be thrown out,” Byrd said.

The first to go was five hundred pounds of gasoline. And upon closer inspection of the cabin, Byrd and Bennett found about two hundred pounds of stuff that was secretly hidden by the crew. The stuff consisted of trinkets, such as flags, pictures, and hats that the crew wanted to make the trip over the North Pole so they would have souvenirs. All the extra stuff was taken off the plane — except for a ukulele that was too well hidden.

Byrd decided that if the weather was still good, they would try again at midnight when the night air was colder, making the snow harder and easier for the plane to take off. He held Igloo in the crux of his arm and boarded a lifeboat, which he rowed back to the Chantier to get some rest before trying again. Neither he nor Bennett had slept in thirty-six hours. Bennett was so exhausted he slept in a sleeping bag in the snow next to the plane, while the crew worked around him, getting the plane ready.

At half past midnight, the sun was shining brightly. Tom Mulroy woke Bennett up.

“All ready,” Mulroy told him.

A crew member was sent to the Chantier, and he alerted Byrd and Igloo that the plane was ready. Byrd and Igloo took a motorboat through the icy waters back to the plane. Byrd knew this was his last chance.

“We were on the ragged edge of failure, and we couldn’t spare an ounce of weight,” Byrd said. “As it was, we had cracked up three times in the snow already. One more smash and it would all be off.”

The runway had been carefully iced in front of the plane’s skis so they could get a quick and smooth start. The engines were warmed up. Byrd and Bennett had one last meeting before heading down the runway. They agreed to go full speed ahead: “Get off or crash.”

With the motors thundering and the propellers whipping up a cloud of snow, Tom Mulroy took his ax and sliced the rope that tied the plane to a stake in the icy runway. Holding his hands on the throttles, Bennett went full speed ahead.

The plane shot down the runway, Igloo chasing after it, all the way down the hill. The plane accelerated, and as it reached the end of the runway, it soared into the air. Igloo looked up and watched Byrd take flight. Then he strutted with satisfaction.

As the Fokker plane flew over the ice-filled bay, it climbed higher and higher, passing over Cape Mitre and reaching an altitude of 2,000 feet. At that moment, Byrd realized he was really on his way to the North Pole. He thought it seemed too good to be true.

On the horizon Byrd could see the ice glint —the shimmering light where the ice and sky met under the bright sun.

“There lay our goal,” said Byrd. “Through that shining curtain we must pass to whatever lay beyond.”

But there were no landmarks on the vast white ice to guide them — there was only the sun. They were relying on Byrd’s navigation skills and tools — the sextant, the drift indicator, and a sun compass to determine their position. Briefly, the thought haunted him.

“Would it be sufficient?” Byrd thought. “Would charts I had and knowledge I had gained of variations be enough to pilot us from land to that indeterminable point — the Pole — and back again?”

The thought quickly escaped his mind once he got to work.

Every three minutes Byrd took readings from the drift indicator and sun compass and made calculations with absolute precision.

“I was jumping from one instrument to another,” he said.

There wasn’t much room to work. The cramped cabin was filled with one-hundred-gallon tanks, radio equipment, loose cans of gasoline, a sled, their food stash, a tent, a rifle, ammunition, smoke bombs, and other emergency landing supplies. This left a narrow aisle for him to walk through, but his bulky fur suit made it a tight squeeze.

Behind one of these tanks was a trapdoor in the floor, which Byrd opened so he could take readings from the drift indicator. Behind the trap door was a shelf where Byrd kept his maps and a sun compass that he used for taking readings through a window.

There was another trapdoor in the roof of the plane. Byrd stood on a box so he could stick his head out the trapdoor. With his nose and cheeks burning from frostbite, he took readings from a sun compass that was attached to the plane’s fuselage.

Directly under the roof’s trapdoor there was a large compass. Since the needle on a compass is a magnet, the compass was placed under the trapdoor so it wouldn’t be affected by the metal on the airplane, which could cause the compass to go haywire. This is known as local magnetism. Byrd also had to take into account the compass’s fluctuations in this part of the world. The force of the magnetism isn’t as strong, causing it to fluctuate. And once the plane passed the magnetic North Pole, which was 1,200 miles to the south of the geographic North Pole (the northernmost point on Earth), the needle of the compass no longer pointed to north — it pointed south.

“We knew our greatest danger was getting off course and that we must fly a straight course to reach the Pole,” Byrd said.

Every half hour or when the gasoline got low, Byrd took over the controls and piloted the plane so Bennett could take a break or pump fuel into the tanks from inside the plane. Byrd kept ahold of the sun compass while flying to take readings and adjust their course.

They were about an hour from the North Pole when Byrd discovered another danger. He looked out the cabin window and saw oil fly by him. A rivet had popped off, and the oil tank had sprung a leak. If the motor ran out of oil, it would die, leaving only two engines. The roar of the engines was too loud for Byrd to talk to Bennett, so he wrote him a note.

At first, Bennett thought they should land the plane. He wrote back, “That motor will stop.”

They both knew it was too dangerous. If they tried to land or take off, they risked crashing. And they were so close to reaching the North Pole.

“There was no way we could get at the tank,” Byrd said. “And after an exchange of notes, we decided we could keep on to the Pole, come what may.”

They went back to work. At 9:02 a.m., on May 9, 1926, Byrd made a note in his diary, which read, “We should be at the Pole now. Make a circle and I will take a picture. Then I want the sun.”

For the next few minutes they circled the Pole and enjoyed the idea that they had “circled the world” in no time flat. The North Pole was a stretch of vast frozen snowy white ice.

“It did not look different from other miles of ice over which we had just passed,” Byrd said.

To mark the occasion, Byrd and Bennett shook hands. Bennett smiled happily at Byrd, and Byrd felt relief for the first time.

“I realized we had accomplished our purpose,” Byrd said.

They decided to head back. The oil was still leaking badly, but the worst was yet to come.

A strong gust of wind suddenly jerked the plane, tipping it to its side. The sextant fell off the shelf, crashing to the floor and breaking. Byrd’s most important instrument was useless. The only way they could make it back now was by using a map, clock, and compass — a process known as dead reckoning.

But to find their way back to Spitsbergen by dead reckoning, Byrd needed a landmark to determine his current position. The sun was his only guidepost. Using his latest measurements, he quickly calculated the sun’s new position. He only had once chance to get it right or he and Bennett risked getting lost for good.

Byrd waited anxiously for the exact time to tell Bennett to fly the plane directly toward the sun. When the time was right, Byrd quickly told Bennett. With its engine still leaking oil, the plane banked and flew steadily into the bright light. Byrd stuck his head out the trapdoor, the Arctic blast burning his face. Peering through his amber goggles, he checked the sun compass. A shadow fell across it, proving his calculations were correct and that they were right on track.

“Surely fate was good to us,” Byrd said, “for without the sun our quest of the Pole would have been hopeless.”

By 4:30 p.m. on May 9 in a cloudless sky, Byrd and Bennett safely landed their plane in Spitsbergen. It took them fifteen and a half hours to fly to the North Pole and back. His crew cheered and threw their hats in the air. Igloo barked as he ran as fast as he could toward Byrd.

Byrd reached down and petted Igloo’s brown ears. “Hello, Igloo,” he said. “We’re going home soon. You’ll be glad to hear that, won’t you?”

Two days later, on May 11, Byrd asked Igloo if he wanted to fly. Igloo hopped into the Fokker airplane without a second thought. The engines roared to life, and the plane raced down the runway, taking off like a bird into the air. Soon after, Amundsen’s dirigible lifted into the sunny sky and followed.

Igloo, Byrd, and Bennett were leading the way on the first leg of Amundsen’s journey to the North Pole. Igloo coolly patrolled the cabin while Bennett and Byrd piloted and navigated the plane. Three days later, Amundsen landed his dirigible in Point Barrow, Alaska, after also successfully flying over the North Pole.

When the Chantier’s rusty anchor was hoisted out of the icy water to begin their journey back to America, Byrd turned to Bennett.

“Now we can fly the Atlantic,” Byrd said, already beginning to plan a nonstop transatlantic flight from New York to Paris. It had been tried by others, but had ended in disaster.

“I hope you take me with you,” Bennett replied.

“We go together,” Byrd promised.

At the time, neither one knew that only one of them would make it.