When Igloo left the land of the midnight sun, it wasn’t the end of his life as an explorer. It was just the beginning. In fact, he would soon discover that his life was full of all kinds of discoveries. Igloo settled into his life on board the ship on his return to New York, and with the excitement of the North Pole flight behind him, everything else almost seemed humdrum. Igloo spent much of his free time playing with his stuffed toy goat.

One highlight of the return trip across the Atlantic for Igloo was the excitement in the radio room. Once the news of Byrd and Bennett’s flight over the North Pole made headlines all over the world, the two men were international heroes. The president of the United States, Calvin Coolidge, wired his congratulations over the radio. In fact, the radio on the ship was lit up and abuzz, and Igloo’s friend Malcolm Hanson was busy fielding congratulatory radio messages nonstop.

When Byrd and Igloo arrived in New York on the morning of June 22, 1926, it was all-out pandemonium. The crowds were cheering wildly, waving flags and hats. It was an earsplitting welcome home, as airplanes flew overhead, ships blew whistles, and fireboats sprayed water like geysers. New York City even closed all of the schools, declaring it a holiday.

With the traffic stopped, Igloo soon found himself in a parade going up Broadway to City Hall. He tried to stay near Byrd while the ticker-tape confetti fell all around them. The noise and mobs of people made Igloo shiver with fear. He didn’t want to get separated from Byrd and get lost in the big city of New York.

Byrd was just as overwhelmed as Igloo by the response.

“All of this was entirely unexpected,” Byrd wrote later. “I felt bewildered. But most grateful that the nation should do this for us.”

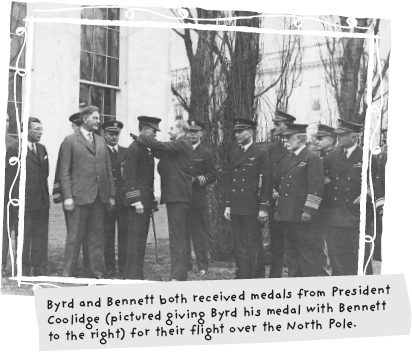

And Byrd’s hero’s welcome was just beginning. After the parade, Igloo boarded a train with Byrd, and the pair traveled to Washington, DC. Technically, Igloo wasn’t allowed on the train — no dogs were. But for Igloo, they made an exception. Once there, President Coolidge presented Byrd and Bennett with medals from the National Geographic Society. Byrd received the Hubbard medal, the highest award, and Bennett received a gold medal “for his distinguished service for flying to the North Pole” with Byrd.

After the president presented the medals, the crowd gradually fell silent. They were waiting for him to speak. Byrd’s face turned pale. He was not used to speaking in front of thousands of people, and it was an imposing crowd — full of influential political leaders. Pushing his fear aside, he spoke up. At first, his voice was low, but it soon gained strength.

“In accepting this medal, I cannot but feel that I am representing the half hundred members of our expedition. I was only one of them. So in their behalf and for our expedition’s sponsors, I want to express our very deep appreciation for this great honor.”

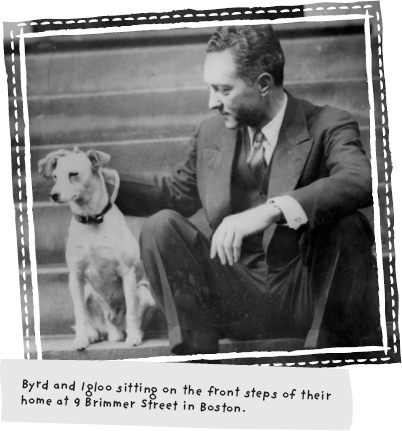

Soon after, Byrd and Igloo arrived in Boston, Massachusetts, the city where Byrd lived when he wasn’t exploring. They were driven to 9 Brimmer Street, a quiet street just around the corner from Charles Street and the Boston Common Frog Pond in Beacon Hill. Their suitcases were unloaded onto the sidewalk in front of a five-story, ivy-covered redbrick townhouse.

They walked up the steps to the front door and into Byrd’s home. Once inside, one couldn’t help but notice that the first-floor ceilings soared fourteen feet high, and the house was shaped like a giant slice of pie — wide at the front and narrow at the back.

But the biggest surprise for Igloo was that Byrd had a family — his wife, Marie, who Byrd had loved from the moment he met her when they were just kids in Virginia, and three children.

Igloo was introduced to Byrd’s six-year-old, curly-haired son, Richard (“Dickie”) Evelyn Byrd III; his four-year-old daughter, Evelyn (“Bolling”), who had strawberry blond hair; and his two-year-old daughter, Katherine.

Igloo also learned that Byrd had two brothers. Harry, Byrd’s older brother, was the governor of Virginia, and Byrd’s younger brother, Tom, was one of the largest apple growers in Maryland. And when Igloo went through the not-so-secret passageways on the second and third floors in the back of the house, he would discover that it led him to Byrd’s father-in-law’s home.

Byrd’s family was delighted to make Igloo’s acquaintance, and the children were eager to be friends with him. Surprisingly, though, Igloo felt shy. He’d never been around children before, and he decided to stick close by Byrd’s side.

Like Byrd’s schedule, Igloo’s was very full. Igloo’s day began very early every morning. Once awake, Igloo would rest his head on his white paws and watch Byrd sleep. Igloo was always extra careful to not make noise and disturb Byrd’s slumber.

Once Byrd was awake, Igloo would snap to attention and watch Byrd perform his morning calisthenics. Then Byrd got dressed and was ready to accompany Igloo into the walnut-paneled dining room. While there, Igloo would watch the fish swim in a gigantic aquarium sitting in the bay window, and Byrd would read the newspaper while they ate breakfast together. Afterward, Byrd and Igloo walked up the staircase to the second floor and into the study. There was a cozy fireplace with bookshelves built around it, and a large globe stood next to the desk where Byrd sat and worked. He had thousands of letters to respond to, books to work on, lectures to give, people to meet, and money to raise for the adventures he was planning.

Igloo curled up contentedly by Byrd’s feet and waited quietly until he was finished. One of the best times of day for Igloo was when he and Byrd took a brisk walk along the Charles River Esplanade. It was during these walks that Byrd would think about plans for his next adventure and Igloo would occasionally find himself chasing squirrels.

But like the candy Igloo couldn’t resist — Igloo had the uncanny ability to hear crinkling candy wrappers at great distances — the children’s madcap games and adventures proved to be irresistible. Byrd’s housekeeper, Norah, who was a strict disciplinarian, said Igloo “caused more trouble than a dozen children.”

But if Byrd ever happened to walk into the room while Igloo was in the midst of playing, Igloo would stop suddenly and act very serious and dignified, as if he hadn’t playing at all. Igloo was a professional explorer, after all, with a reputation at stake. And he and Byrd had a lot of work to do if Byrd was going to be the first to fly nonstop across the Atlantic.

In the spring of 1927, the ongoing race to be the first to fly an airplane nonstop from New York to Paris had heated up. Raymond Orteig, a Frenchmen who had made a name for himself as a top-notch restaurateur and hotelier in New York, became interested in aviation during World War I, when countless aviators stayed at his hotel. In 1919, he offered a $25,000 prize to the first person to succeed. Many attempts had been made, all ending in disaster — with two men burning to death in a fiery plane crash. In the summer of 1927 alone, thirty people would die trying to make the trip.

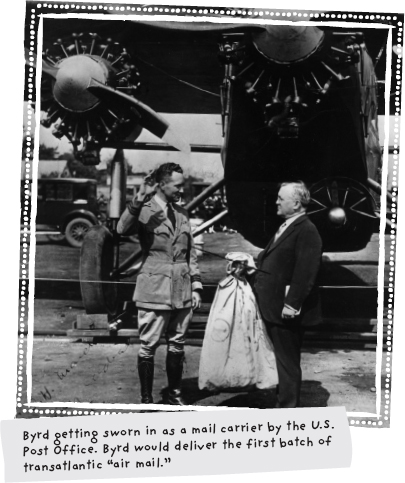

Byrd wasn’t interested in the prize money. In fact, he never officially entered the contest. At the time, little was known about flying long distances with heavy loads. And if Byrd could successfully fly across the Atlantic in a heavy trimotor plane, then he could prove that commercial oceanic flights were not only possible but practical, thereby opening the doors for the development of an airline industry. So Byrd packed his bags, and he and Igloo headed for New York, the starting point for the race to fly nonstop over the Atlantic.

For this flight, Byrd again carefully chose his airplane, a Fokker trimotor, and helped design some special features, paying particular attention to safety. One special feature was a safety valve Byrd developed. If the plane was about to crash, a valve could be pulled to dump the gasoline from the engines and prevent a fire. Byrd’s copilot on the flight, Floyd Bennett, requested a switch that would shut down the three engines all at once if a crash landing was unavoidable. Byrd and Bennett also had catwalks added to the outside of the plane so they could fix mechanical problems mid-flight — they would just have to hang on tight.

With a crew of four, eight hundred pounds of emergency supplies and equipment, eight hundred gallons of gasoline in the tank alone, and radio equipment, the plane was heavy. So Byrd had a specially designed runway built at Roosevelt Field on Long Island, New York. The runway was longer and built down a hill. The downward slope allowed the plane to reach a faster speed for takeoff.

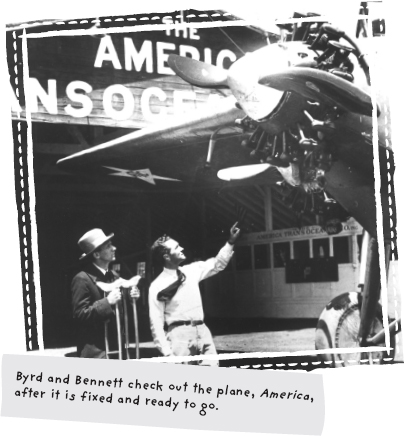

It was late in the afternoon at the Teterboro Airport near Hasbrouck Heights, New Jersey, on April 20, 1927, when Igloo watched Byrd climb into his recently built plane, America. Byrd was accompanying Anthony Fokker, the designer of the plane and vice president of the Atlantic Aircraft Corporation, on its first test flight.

Also along for the ride were Byrd’s crew members for the transatlantic crossing. Floyd Bennett was in the cockpit next to Fokker, who was at the controls. Behind them, Byrd was standing in the navigator’s cockpit next to the broad-shouldered George Noville. Noville, who had been with Byrd on the North Pole expedition, was going to operate the radio and fill in as a relief pilot on the crossing.

The sky was hazy when the plane took off. It soared into the sky and everything was running smoothly. The flight was perfect — until they tried to land. That’s when Byrd saw Bennett lick his lips.

“This is the only sign Bennett gives when he is nervous — which I may say, is very rare,” said Byrd.

When Fokker cut the engines to bring it in for a landing, the plane took a nosedive at a breakneck speed. Fokker yanked the throttle, pulling the plane back up into the air. He looked back at Byrd.

They knew the outlook was grim. There was too much weight in the front of the plane, and the fuel tank, which was running on empty, was blocking Byrd and Noville from the back of the plane. There was no way to distribute the weight and balance the plane.

“We’ve got to come down anyway,” said Byrd.

Byrd and Noville crouched down, holding on to the seats in front of them. Fokker cut the throttle, and the plane’s two front wheels touched the ground. Fokker opened the trapdoor overhead, and was flung headfirst out of the plane. The plane sped along the runway, kicking up dust, as the tail of the plane kept rising, higher and higher. Suddenly, the plane went over its nose. The center propeller was ripped off, and the front end of the plane was smashed in like an accordion as the plane somersaulted and landed on its back.

Igloo felt sheer panic in his heart, and he tore across the runway.

Inside, Byrd, Bennett, and Noville were trapped. Byrd’s arm had snapped like a dry twig from the impact.

“Look out for fire!” cried Bennett weakly.

Everyone was worried that a fire would break out and they would burn alive. Noville, who was in terrible pain from internal injuries, frantically tore a hole through the fabric walls of the fuselage. He climbed out, and Byrd followed.

Once on the ground, Byrd looked for Bennett. He heard a cry from the plane, and rushed back inside.

Bennett was still trapped in his pilot’s seat, hanging upside down. He’d received the full force of the impact from the crash when an engine slammed into him. There were two big gashes on his head. His face was covered in blood and his body was drenched in oil. His leg was broken above his knee, his right shoulder was dislocated, and a rib was broken. The pain was so bad he was barely conscious.

“Guess I’m done for,” said Bennett. “I’m all broken up. I can’t see and I have no feeling in my left arm.”

Byrd tried to reassure him, not wanting to let on that things looked bad. Very bad. With one hand, Byrd wiped the blood and oil out of Bennett’s eyes. Others came and helped Byrd cut Bennett free.

Everyone was rushed to the hospital. On the way, Byrd grimaced as he set his own broken arm.

The next time Igloo saw Byrd, his arm was in a sling and the worry lines in his face had deepened. But Byrd was relieved that Bennett had miraculously survived the crash. When Byrd saw Igloo, he couldn’t help but smile.

“It might have been worse, Igloo,” said Byrd. “We’re going to try again. We’re going to rebuild the plane and we’ll be in Paris before long.”

Igloo moved closer to Byrd. Then he gently licked Byrd’s hand.

Byrd’s next attempt came more than two months later on June 29, 1927. Although Charles “Lucky Lindy” Lindbergh had already successfully crossed the Atlantic in a single engine plane all by himself, Byrd’s enthusiasm had not waned despite the fact that Bennett wouldn’t be flying with him.

Bennett was still in the hospital. His right leg was in a cast, and his left leg was braced with steel splints and bandages. Nevertheless, he would be with Byrd and his crew the whole way — listening for bulletins on the radio by his hospital bed.

Replacing Bennett as the copilot was mustached Bert Acosta, a renowned stunt flier and naval reserve officer. The other copilot was Norwegian Bernt Balchen, who had helped Byrd fix his plane’s skis for Byrd’s North Pole flight. Balchen could also fly an airplane by just using the instruments, which was invaluable.

George Noville, who had recovered from his injuries, had an extremely important job on the flight. As the radio operator, he would be communicating with the steamships on the Atlantic Ocean. The steamships would transmit the weather reports to him, which would help Byrd navigate along the way.

For weeks, the weather, which was critical to their success, hadn’t been cooperating. Constant rain and fog had delayed their departure date.

At 1 a.m. on June 29, 1927, Byrd had only been asleep for an hour when he and Igloo were startled awake by the telephone ringing. It was the weather bureau. Byrd was told the weather was as good as it would get. Byrd quickly phoned his crew. By dawn, Byrd and his crew were ready for takeoff.

In the drizzling rain, Igloo was standing near Tom, Byrd’s younger brother, as he watched the plane speed down the runway. When the plane lifted into the air, Tom heard a “half-choked sound, almost like a cry” from Igloo. Igloo tugged on his leash, trying to break free. It was only when the plane was high in the sky that Igloo finally stopped pulling.

With Byrd gone, Igloo was miserable. It wasn’t until later, when he caught a glimpse of a woodchuck and chased it at full speed that Igloo felt his spirits lift.

Up in the air, just north of Halifax, Canada, Byrd looked through the plane’s trapdoor. He saw a beautiful bright rainbow, and it seemed to be moving with the plane.

“I could not help but think it was an augury of a good omen,” said Byrd.

But that was wishful thinking.

For the next forty-two hours the rain and fog were relentless.

“We were lost several times,” said Byrd. “But I always knew approximately where we were.”

They flew their plane at a high altitude, which usually kept them out of the fog and clouds. But even at higher altitudes, they were forced to fly through enormous clouds. This was dangerous since ice could form on the plane’s wings, causing the plane to fall out of the sky.

“During the dark hours when I was working on my charts,” said Byrd, “I could tell when we were in a thick cloud by the water dripping into the navigator’s cabin.”

With the persistent fog and clouds, Byrd and his crew were forced to fly blind for nineteen hours. That is, they flew without seeing land, water, or a clear sky.

“We did not find it a very agreeable sensation,” said Byrd.

But Balchen’s skill at instrument flying was a lifesaver. Even so, by the time they reached the fog-covered Paris, their compasses went out, fuel was low, and they needed to find a place to land — soon. When Byrd looked out the window, it was as dark as black ink.

Byrd had to make a decision, and it was do-or-die.

“In the confusion of the storm, we were afraid we might run out of gas and have to land in the dark and perhaps kill someone, not to speak of ourselves,” said Byrd.

Byrd knew what they had to do. He signaled to Balchen, who was piloting the plane, to circle back to the coastal village of Ver-sur-Mer, near Normandy. Once there, Byrd dropped flares out of the trapdoor. When they hit the water, the flares illuminated the ocean beneath them. For a few short minutes, there would be light.

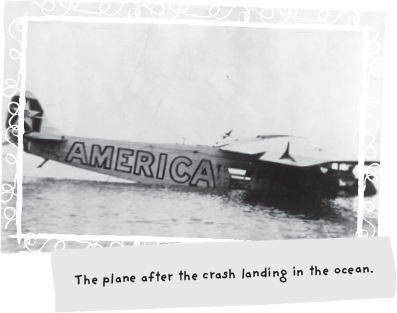

With only one choice left, Balchen circled the plane around the light and descended, hurtling toward the ocean.

“It was amazing the force of the water as we hit,” said Byrd. “It sheared off the landing gear … as if it had been of straw … then the bottom of the fuselage ripped open and the plane filled with water instantly.”

Byrd shot out a window. He had been hit in the chest, and his heart was thumping. He swam over to where he thought he heard Noville shouting his name. Byrd called out, but they were all having trouble hearing. The constant roar of the engines had their ears ringing.

Through the darkness, Byrd could faintly see Noville climb out a window. Relieved that Noville appeared to be okay, Byrd swam to the cockpit. He reached in and found Balchen, who was dazed but in the process of freeing himself. Byrd grabbed Balchen by the back of his neck and pulled him out of the plane.

Byrd yelled at the top of his lungs for Acosta. There was no answer. They looked through the window into the cabin but there was no one there. Byrd noticed the wing of the plane was underwater and so was the fuselage. He feared the worst — that Acosta was trapped underwater. They yelled and yelled for him. But there was no reply.

They were treading in the cold water, with darkness surrounding them, when Acosta suddenly appeared — alive and well despite a broken collarbone.

“Believe me,” said Byrd. “I was the happiest man in the world.”

When Byrd finally returned to 9 Brimmer Street — after receiving a second ticker-tape parade in New York for his transatlantic flight — Igloo was overjoyed to see him. He had missed Byrd terribly. Since he couldn’t tell Byrd how happy he was to see him again, he decided to show him.

Igloo went into the living room, where there was a table and chair that was once owned by Napoleon. Byrd kept his charts and maps from the North Pole on the table, and Igloo stored his toy goat under Napoleon’s chair. Without hesitating, Igloo grabbed his beloved stuffed toy goat and went back over to Byrd. Igloo looked up at Byrd and dropped his toy goat at Byrd’s feet, giving Byrd his most precious belonging.

Byrd responded in kind.

“Would you like to go for a walk, Igloo?”

It was exactly what Igloo wanted to hear. There was nothing Igloo wanted more — being with Byrd was his most favorite thing in the whole world.

It wasn’t long after that that a worrisome thought crept into Igloo’s mind. He learned that Byrd was making plans to go to the Antarctic to fly across the South Pole, which had never been done before.

The Antarctic is the coldest, driest, windiest, and iciest place in the world, with normal temperatures well below freezing. At the time, very little was known about the continent.

“The ice-barrier, the frightful weather, and the lack of animal life are a few of the things that have hampered exploration,” said Byrd. “Taken together they form almost insuperable obstacles.”

But Byrd knew one thing for sure. Flying to the South Pole would be more treacherous than flying to the North Pole.

While Byrd spent hours planning for his most dangerous feat yet, Igloo was worried — worried that he would be left behind. After all, he didn’t get to fly across the Atlantic. But Igloo had a plan.

In the meantime, Byrd chose Bennett to be second-in-command on the expedition to Antarctica. Even though Bennett was still weak from his injuries from the crash, he had happily taken care of nearly half of their preparations.

“Everything that has to do with transportation is in his hands,” said Byrd. “And I do not have to worry about it.”

Bennett, whose nerves were still like steel, tested the three planes they were taking on the trip. Bennett even flew the big Ford trimotor plane, which Byrd planned to fly over the South Pole, in northern Canada where the temperature was thirty-five degrees below zero.

But four months before the first ship was to set sail to Antarctica, Bennett piloted a rescue flight to save the lives of four marooned flyers who had set out to fly across the Atlantic, but were forced to crash-land on Greenly Island in Canada.

The 1,500-mile flight in subzero temperatures proved to be too much for Bennett’s weakened condition. Several days later Bennett died from pneumonia with Byrd at his bedside. Byrd was grief stricken.

“Bennett was one of the coolest and bravest men I ever knew,” said Byrd. “He was a man of the greatest energy, endurance, and skill, both as a navigator and as a mechanic.”

After the sudden death of his trusted friend, the Antarctic expedition almost didn’t happen. But it soon took on a new meaning for Byrd.

“I intend to go through with the Antarctic expedition as a memorial to Floyd Bennett,” Byrd announced in a message. “I shall name the Antarctic plane to be used in an attempt to fly over the Pole Floyd Bennett.”

But it would never be the same without Bennett.

“Hundreds were the times I was to feel his loss,” said Byrd.

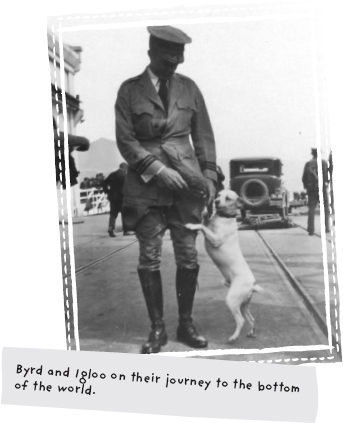

On the day of Byrd’s departure, Igloo knew it was time to put his well-thought-out plan into action. First, he was on his very best behavior. Second, he kept a close eye on Byrd, never leaving his side, following him up and down the staircase, while Byrd piled his suitcases near the front door. Finally, when Byrd set the last one down, Igloo planted himself firmly by the tower of suitcases. Mission accomplished.

When the taxi arrived, Igloo watched Byrd and his family hug and kiss. It was a tearful good-bye. It would be years before he would see them again — if he survived. The New York Times newspaper had already written an obituary for every person going on the expedition, expecting someone — if not all of them — to die.

Byrd opened the car door and took a seat. Then he turned and shouted, “Hop in, Igloo! We’re in a hurry.”

Igloo’s heart soared, and he leaped onto Byrd’s lap. As the taxi sped away, Igloo looked out the window and barked enthusiastically. He and Byrd were once again on a great adventure, together, headed to the bottom of the world.