After a long train ride from New York to California — which ran behind schedule when Igloo decided to take off and chase a gopher — Igloo found himself with Byrd on a steel whaling ship, the C.A. Larsen. Their oceanic journey began when they set sail from the Port of Los Angeles on October 10, 1928. For the first leg of the 10,000-mile trip to the bottom of the world, it was smooth sailing for Igloo.

The Larsen was one of three ships that Byrd was using to haul the men, supplies, equipment, and three airplanes to the Antarctic. The other two, the Eleanor Bolling (named after Byrd’s mom, who was also the namesake of Byrd’s oldest daughter) and the City of New York, had left from different ports. The three ships planned to meet in New Zealand to resupply, refuel, and reload before embarking on the last leg of the journey — the most dangerous part — through the maze of menacing ice.

Igloo felt right at home on the Larsen, and as always, he had full run of the ship. But after his first once-over below deck, he steadfastly refused to go down below again. No matter what Byrd said to try to convince him otherwise, Igloo kept his distance.

Byrd suspected that the cow, which was brought along to supply fresh milk and was living down below, might be the reason Igloo refused. That may have been true, but there may have been another very good reason, too.

While Byrd was busy, checking the supply lists, making plans, and discussing the ice conditions with the captain, sometimes for several hours, Igloo was very busy, too.

Igloo’s favorite pastime on board the Larsen was hiding under Byrd’s deck chair on the main deck of the ship. Like a lion stalking his prey, Igloo crouched down on his haunches and waited patiently for just the right moment. Then, when he spotted a crew member who was unwittingly walking by Byrd’s chair, Igloo suddenly shot out from under it.

Feigning an attack, Igloo barked savagely and enjoyed scaring the living daylights out of the unsuspecting sailor. Nonetheless, Igloo always wagged his tail at him, letting him know it was all in good fun — albeit at his expense.

“Neither modesty nor humility, I regret to say, was in his attitude,” said Byrd.

However, Igloo was always very careful to avoid pulling his prank on the officers. He knew how to spot them. The high-ranking officers wore lots of brass buttons. In fact, whenever Igloo was in an officer’s presence, or in the presence of anyone who had authority, he was always “the very picture of innocence.”

But Igloo’s fun and games came to an abrupt halt on December 2, 1928. This was the day he and Byrd set sail on the City of New York for the second leg of their journey. And when Igloo went out for a stroll on the poop deck toward the back of the ship, he finally met his match.

The City of New York was old and slow, but it wasn’t an ordinary steamship. It was an ice ship. And, unlike other steamships, the City had a V-shaped hull covered with tough and slippery wood. This helped lift the ship out of the water so it wasn’t crushed by the ice. The bow of the ship was outfitted with heavy steel plates, and the sides of the ship, which were three-feet thick, were reinforced with cross timbers to prevent it from being crushed by the ice.

Although the City was one of the larger ice ships, it was jam-packed and overflowing with all of the supplies Byrd was taking to the Antarctic. Igloo was overwhelmed by the mountainous piles of boxes and crates towering over him, threatening to topple over. But there was a lot to bring on the expedition.

There were eighty-three men on the three ships, and forty-one men who would be staying with Byrd in the Antarctic. With so many mouths to feed, a lot of planning went in to the supply of food, which is scarce in the Antarctic. Plants did not grow there, and animals, such as seals, penguins, and whales, were the only source of meat along the coast. Farther inland there was no food at all.

The task of creating a food budget, buying the food, and planning menus fell on the shoulders of Igloo’s good friend Cook Tennant; oval-faced Sidney Greason, the chief steward on the expedition; and Dr. Francis Coman, the expedition’s physician, who Igloo would soon know quite well.

“It’s quite a job to know just what and how much food to take on for two years,” said Cook Tennant.

They paid particular attention to how the food was packaged. It couldn’t be stored in heavy, breakable glass jars. And it couldn’t be stored in tin cans. The cold temperatures cause glass jars to burst and tin to become brittle. A noncorrosive metal, such as a nickel-copper alloy, would have to be used. Plastic was not considered since it hadn’t been invented yet.

Greason, who had fifteen years of experience as a butcher, did not skimp on quality and personally picked out every ham and turkey himself.

“I’m buying the best…. If I have any claim to distinction, it is that I know good food, and that I get it,” he said.

As a result, there were twenty-five tons of chicken, turkey, beef, ham, hot dogs, and bacon to haul to the Antarctic, 2,500 pounds of pemmican, 2,000 pounds of cocoa, and 3,000 pounds of powdered milk, not to mention loads of canned and dehydrated fruits and vegetables.

Enormous amounts of flour were also purchased so bread, rolls, and pies could be baked every day. They also bought large quantities of birthday candles so everyone’s birthday could be properly celebrated.

“No man … is going to have a chance to sigh for home cooking or for pies like Mother used to make,” said Greason, “because he is going to have them all while he is gone. Change of scenery is going to mean no change of food.”

While the crew was busy loading and stacking all of these crates, Igloo knew to stay out of the way while he explored the ship. When he made his way down the stairs and into the forecastle, or fo’c’s’le, which was in the front of the ship and where the crew’s quarters were located, Igloo’s body suddenly stiffened and he twitched his nose. He had caught a whiff of the musty, stale air that was damp from the saltwater and thick from tobacco smoke. The odor was unpleasant, but it didn’t deter him.

Through the darkened hallway, weaving in and out of crates, Igloo passed by the cramped rooms filled with wooden bunk beds and overflowing with personal belongings and gear.

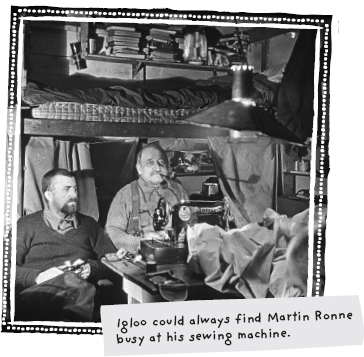

When Igloo made his way to the aft, or back of the ship, there were piles and piles of animal furs. On the expedition, each person would wear a fur snowsuit. And the person in charge of sewing all of the polar clothes was sixty-eight-year-old Norwegian sail maker, Martin Ronne. The suspender-wearing Ronne was the oldest person on the expedition and the only one who had ever been to the Antarctic before — back in 1911, when Amundsen was the first person to set foot on the South Pole. Amundsen had recommended him to Byrd because Ronne was not only the best sail maker in the polar-exploring business; he was also the best tailor of polar clothes.

Igloo could always find Ronne sitting busily behind his sewing machine making fur parkas, pants, boots, sleeping bags, tents, and sails. Ronne could sew it all, paying particular attention to the type of fur and the size. Although Byrd brought along the polar-bear-fur pants that he wore to the North Pole, Ronne was making the crew’s pants out of caribou skin with the fur side facing out. Inside they were lined with fawn or squirrel skin.

“In making up all these garments the rule must be remembered that fur outside keeps the cold out, and fur inside keeps the warmth in,” said Byrd.

The boots were of utmost importance. Sweaty feet were a big problem, and sweat will freeze, causing frostbite. In the Antarctic, it’s easy to lose toes to frostbite, especially when temperatures reach seventy-five degrees below zero.

To solve this serious problem, Ronne made the boot bigger. A bigger boot gave room for at least two pairs of socks — one made out of caribou skin and the other made out of wool.

To wick moisture away from the socks, the boots were stuffed with a dry, haylike grass called senna from the foot of the boot to halfway to the top. The final problem to work out was that the jagged ice wore the boots out quickly. Sealskin, which is tough and waterproof, was used on the soles of the boots to fix this problem. The upper part of the boot was made of caribou skin.

Like the boots, the gloves were made of caribou and sealskin and were oversized so wool mittens could fit inside. The sleeping bags were also made of caribou skin.

Along with the fur snowsuits, the men needed to bring skis, ski boots made of kangaroo hide, ski suits, windbreakers, long underwear, and sun goggles. And since the crew would have to provide their own entertainment during the long, dark winter days, they also packed plenty of musical instruments, like ukuleles, banjos, guitars, saxophones, and even a piano.

Unlike the men, Igloo had packed lightly. He’d just brought along his new favorite toy — a little rubber ball with the face of a cat on one side of it. He loved the way it squeaked when he squeezed it because it sounded like a “meow.”

As Igloo continued to explore the ship, it wasn’t long before he found himself on the poop deck. And it was there that he was about to lose something very important to him.

As Igloo wandered along the dirt-covered deck and through the piles of gear and boxes, something caught his eye. Dozens of wooden crates with wire mesh doors were scattered and anchored all around the poop deck and on top of the gigantic crate that contained Byrd’s Ford airplane, the one he planned to fly over the South Pole.

Igloo’s nose twitched. There was a familiar scent in the air. Curious, Igloo walked over to investigate, looking through the mesh wire and into the dark crate. This was a big mistake.

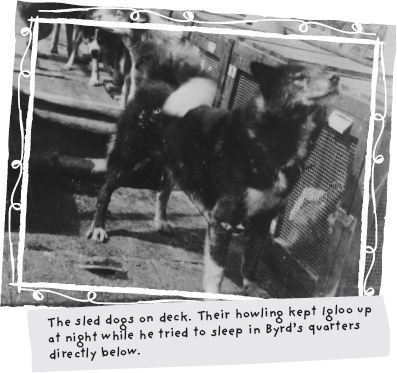

A giant dog with ferocious-looking fangs hurled his massive body against the mesh wire, barking wildly and trying to attack Igloo. Suddenly, there was vicious growling and barking all around him, as the Eskimo sled dogs tried to free themselves, hoping to rip Igloo to shreds.

Igloo’s body trembled, shaking uncontrollably with fear. His brown-green eyes flashed wildly around as he tried to decide what to do. His white tail went up in a friendly manner, and then it went down in surrender. Up. Down. Up. Down.

Igloo quickly came to his senses and ran with his tail between his legs as fast as he could — only to find more dogs leashed to the ships railing, straining and rattling their chains, fangs snarling trying to sink their teeth into Igloo as he flew by.

Igloo kept running. And running. And running. He never slowed down, not even when he was safely below deck. He ran at top speed through the fo’c’s’le, and kept on running and running.

When Igloo finally had a chance to collect himself, he realized he’d lost something very important up on the poop deck — he had lost his courage.

“Until this trip,” said Byrd, “I fancied neither man nor beast could discompose him. He met his superiors, however, in the Eskimo dogs, and in admitting to himself their superiority, his spirit underwent an extraordinary change. He hardly dared venture on deck alone…. Poor Igloo, I did not blame him. Those huge creatures would assassinate him on the spot, as he was shrewd enough to realize.”

And Byrd was shrewd enough to realize that sled dogs were critical to the survival of the men on the expedition. Their job was to haul the supplies over the snow, ice, and deadly crevasses to the campsite where the crew would be busy building underground houses for shelter.

The most famous sled dog on the expedition was Chinook, who was part Eskimo husky and part mutt. He was big, at one hundred pounds, with a golden coat of fur and silver muzzle. Chinook’s grandfather had been Robert Peary’s lead sled dog when he discovered the North Pole in 1909. Chinook was considered the world’s greatest sled dog of all time, having won one of the first international sled dog races in 1922.

Chinook’s driver, the grizzled Arthur Walden, was considered the best sled-dog driver in the country. Part of their success together was their deep bond of love and respect for each other.

“He is eleven years old and the greatest leader I have ever known,” Walden said about Chinook. “We will keep him reserved to take the lead in case of emergencies. Nothing can stop him.”

Although Byrd was bringing the most cutting-edge technology with him to the Antarctic, he knew that mechanical equipment was prone to failing in extremely cold weather. But sled dogs were tried and true and had been proven to be the most reliable transportation in the Antarctic.

“Dogs you see, are the only animal to use down there,” said Walden. “The dog doesn’t sweat, so he can do hard work and then lie right down on the ice and sleep. He doesn’t need water, and he can go five days without food and still do hard work.”

Even so, Igloo didn’t like the sled dogs one bit. They terrified him. And it didn’t help that night after night, the sled dogs threw their heads back and howled a mournful, eerie moan. It would start with one howl and then the other dogs would join in.

While the dogs howled, directly below them, in Byrd and Igloo’s room, Igloo couldn’t sleep. Haunted, he shivered with fear and hid behind a box and under his blanket. It wasn’t until the howling stopped that he risked coming out. But the howling soon got worse.

Fierce storms rolled in and brutal waves soaked the men and dogs as the ship rolled dangerously back and forth and up and down. Unhappy, the sled dogs howled all day and night.

As the days passed, the nights grew shorter as the summer months approached the Southern Hemisphere. The stormy weather subsided, but the ship was soon dodging icebergs, and by December 15, there was thick ice everywhere. The ship had reached the pack ice.

Breaking through the thick ice pack without sinking is tricky. The Bolling had already turned around to go back to New Zealand because it had been unable to break through the ice.

The City couldn’t make it through the pack ice on its own, either. It didn’t have enough engine power. So the crew used a three-and-a-half-inch thick wire cable that was attached to the Larsen and the City. Taking the lead, the Larsen cautiously pushed her bow against the ice and then lurched forward at full speed, breaking through. As the Larsen sped ahead, it pulled the City through the watery opening. The noise from the breaking ice was so deafening as to be almost unbearable.

“Down below, in the fo’c’s’le, it is like standing in a chamber the walls of which are being pounded with giant hammers,” said Byrd. “There would come an impact, the deck would tilt alarmingly, then the ship would sag with groaning timbers and the shriek of cracking ice would sound outside.”

When the ice broke apart, there was a period of calm as the ship was pulled through, and it was during this time, two days later, when Igloo cautiously went up onto the main deck — keeping his distance from the sled dogs.

Igloo tried to tune out the barking sled dogs and enjoy himself. After all, Cook Tennant had made him roast lamb for lunch, and he was feeling pretty good. He stationed himself near a trusted crew member and knew Byrd wasn’t far away. He was busy in the chart room. Igloo gazed out at the endless barren ice when he caught a glimpse of something moving.

He got up from his spot and scurried over to the railing to get a better look. But there was nothing there. Then he saw something move again. And it was coming right toward him.

Waddling on the ice and coming right up to the side of the ship was a three-foot-tall emperor penguin. Igloo stood up on his hind legs, his two front paws resting on the railing. He looked hard at the black-and-white penguin with bright yellow ear patches. Igloo barked at it happily. Then the emperor penguin disappeared among the ice.

The ship once again began hammering through the ice when Igloo saw two small Adélie penguins pop up onto the ice. They tilted their heads to their sides, waved their flippers, and shuffled toward the ship. Igloo was beside himself, and he ran up and down the deck, barking.

“There was great hilarity aboard for awhile,” said Byrd. “These comical creatures came to us unafraid, with friendly waves of flippers, tobogganing with great speed on their bellies across ice floes.”

Some of the crew jumped off the ship onto the ice to play with the penguins. Igloo tried to jump off, too. But his plan was thwarted when someone grabbed his collar before he could join in on the fun. Nevertheless, as long as the Adélie penguins were nearby, Igloo didn’t take his eyes off of them.

Soon the ice became slushy like thick soup, and Igloo and Byrd were on the open water in the Ross Sea. The Larsen was no longer needed to pull the City through the ice pack, so it turned around to go hunting for whales, leaving Byrd, Igloo, and the crew aboard the City to fend for themselves.

Two days later, on Christmas Day, there was a shout from high above in the ship’s crow’s nest: “Barrier on the starboard bow!”

Some of the crew were eating, and quickly pushed their plates aside. Everyone ran to the upper deck, eager for a better look at the mysterious Ross Ice Shelf, the largest floating body of glacier ice in the world.

With its towering, spiky wall and overhanging ice cliffs, it looked blue when the light from the sun fell on it. This was the place where Byrd and Igloo and the rest of crew would be living for the next year. And it was also the place where Igloo was about to rediscover his courage.