JANUARY 1929, ANTARCTICA

Igloo listened to the sounds of dogs barking, men shouting, and ice cracking. The noise pierced the deep, ever-present Antarctic silence. Once the ship had reached the recess in front of the Ross Ice Shelf, called the Bay of Whales, the crew hammered two-hundred-pound ice anchors into the solid pack ice, mooring the ship.

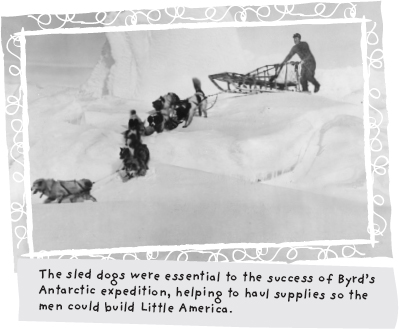

Not long after, Byrd found a spot where they would build their winter base, which he dubbed “Little America.” The base was nine miles from the ship, which was a long distance to haul their supplies, especially with the constant threat of hidden ice crevasses. A fall into a crevasse by a crew member or dog would most likely be fatal. But it was important that the base was far enough away from the bay in case the ice broke off and floated out to sea.

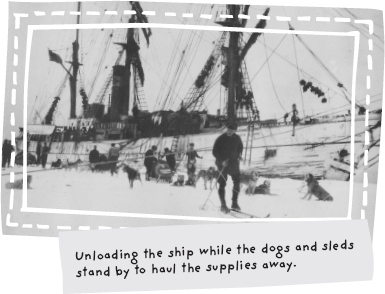

Byrd and his team had their work cut out for them. Unloading and moving the supplies was a grueling, nonstop task that exhausted everyone. It would take months to complete, and they had to be finished before winter came and the sun disappeared for four months.

At the North and South Poles, there are two seasons, winter and summer, and they begin and end at opposite times. In the Southern Hemisphere, where the South Pole is located, the winter season begins near the end of March and lasts until the end of September, unlike in the Northern Hemisphere, where the North Pole is located, and where winter begins near the end of September and lasts until the end of March. This has to do with the tilt of the Earth’s axis. In December, the Northern Hemisphere is tilted away from the sun, making it colder. But the Southern Hemisphere it tilted toward the sun, making it warmer.

For weeks now, Igloo and the penguins, groups of which were always nearby, watched the steady stream of boxes, crates, and barrels of supplies making their way down the wooden planks. Once the supplies were off the ship, they were hauled to Little America, a job that fell on the sled dogs.

As the sled dogs stepped off the ship and onto the ice for the first time, finally free from their cages, they were wildly excited, rolling in the snow, running in circles, and sometimes pouncing at one another’s throats. Nevertheless, they were always eager to start work, trotting to their places, waiting to be harnessed.

The sled dogs and their drivers settled into their new home at Little America. The dogs slept in crates or buried themselves in the snow — with the exception of Chinook, who slept in a tent with Walden. Every morning after a quick cup of coffee, the sled-dog drivers cracked their whips and yelled yake! for straight ahead, gee! to turn right, haw! to turn left, and whoa! to slow down. Soon after, they would arrive at the ship to haul more supplies back to Little America. And whenever the dogs were nearby, Igloo was on full alert.

Igloo knew that if he kept out of their way, the sled dogs left him alone. He always paid close attention to when the dogs were harnessed to their wooden sleds, providing him with a little more security.

For safety, the ten-dog sled teams always worked in pairs. And someone always watched over them from the ship’s crow’s nest while they made two dangerous trips a day over shifting ice, running through the snow as fast as they could to Little America.

On January 17, Igloo and the others noticed that Chinook never arrived at the ship. This wasn’t too unusual. Sometimes, he didn’t lead the dogs when Walden didn’t want him to get overworked. During those times, Chinook usually ran ahead or behind the sled, just to keep his eye on things. Whenever there was a difficult trail to follow, Walden could depend on Chinook.

But this time, Chinook had been running behind the team as they made their way toward the ship. He fell far behind, and when Walden looked, Chinook was nowhere to be seen. Some of the men were worried that Chinook had fallen into a crevasse.

“No,” Walden said. He knew Chinook better than anyone. “Chinook was downed by three of the other dogs the day before and that means in a pack of husky dogs that he lost his leadership. He was never off his feet in a dog fight before…. He figured it all out. He was all through. And he came and bid me good-bye, but I didn’t realize what he was doing until later. Then he walked off alone to find a place to die…. I dream of that dog yet. I can’t get him out of my mind.”

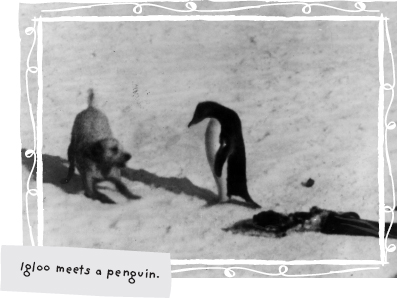

Like Igloo, the younger Adélie penguins also found the sled dogs interesting. But unlike Igloo, the penguins didn’t know to keep a safe distance. Whenever the sled dogs were harnessed, waiting for the supplies to be loaded on their sleds, the penguins would make a dash toward them, waving their tiny wings.

The dogs waited patiently for the penguins to get close, and when they did, the dogs snapped and barked in attack. Many times Igloo witnessed penguins waddling away in pain, and sometimes the penguins had to be pulled from the dogs’ clenched jaws, the snow red from their blood. Igloo tried to run interference to stop them, but the penguins always refused to listen.

Although Igloo kept his distance from the dogs, he knew them from afar. There was Spy, a sled-dog leader. He was a big snow-white husky. His brothers, Watch and Moody, were part of his team. They were friendly to everyone, always holding out their paws, ready for a handshake. The brothers were devoted to one another, earning the nickname “the Three Musketeers.”

There was also the plump husky dog named Moose-Moss-Mouse, so named because he looked like both a moose and mouse with a mossy coat. Moose-Moss-Mouse only had one eye, having lost the other in a fight. Some thought he was ugly, but his dog-team driver, Norwegian Chris Braathen, loved him and said that Moose-Moss-Mouse was “the best dog that ever was.” Moose-Moss-Mouse’s best friend was Tickle, a skinny but strong lead dog with black fur and a lot of pluck.

One day, while Igloo was busy doing his daily inspection around the ship, with no intention of making trouble, Tickle caught his eye. Igloo noticed Tickle and his team were harnessed securely to the sled. There was nothing unusual about that, but a thought suddenly occurred to Igloo, giving him an idea — one that he found not only foolproof but also irresistible.

Setting his sights on Tickle, Igloo charged at top speed right toward him and his team. When Igloo was just inches away, his plan was to veer away, wanting only to taunt Tickle. But the slippery ice betrayed him. And while he frantically tried to slow down, leaning back and dragging his rump across the ice, Igloo slid right into the middle of the pack of dogs.

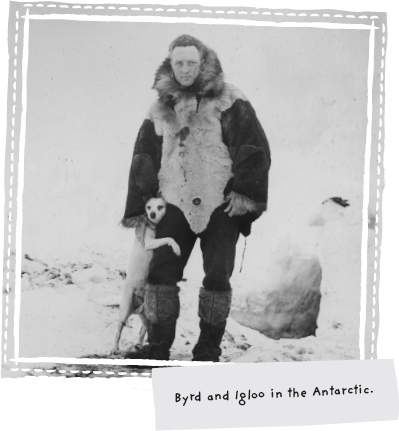

The dogs immediately pounced on Igloo. They barked angrily, and Igloo’s yelps for help could barely be heard buried beneath the ferocious growls. But Byrd heard him, and in a flash, he and Tickle’s driver, George Thorne, rushed to the pileup of dogs. Using a whip and club, they broke up the fight. Byrd was sick with dread, fearing Igloo was at the bottom of the pile — dead.

But Igloo didn’t have a single scratch. Everyone, including Igloo, was surprised. Igloo stood unsteadily on his tiny feet, shocked and shaking. He managed a slight upward glance at Byrd and a little wag of his tail. He didn’t protest as Byrd led him back to the ship. Instead, Igloo stayed right next to Byrd. But Igloo had discovered something very important in the pileup, and he was certain the other dogs knew it, too. With Byrd by his side, Igloo was the top dog.

Buoyed by this thought, Igloo devised a new game that delighted him, but he only played it when the sled dogs were harnessed. Now, whenever the sled dogs ran by, pulling the heavily loaded sled, Igloo would run as fast as he could alongside them, but not close enough that they could reach him. His game made the dogs so angry that they would get tangled up in the harness, and sometimes the sled toppled over. It wasn’t long before Igloo was no longer allowed near the sled dogs, much to his chagrin.

So Igloo shifted his attention to the penguins. He favored the smaller and friendlier Adélies over the emperors. Whenever he saw them, Igloo wagged his tail in a friendly wave and he greeted them with happy noises. He liked to line the Adélies up in a row and tackle them. It was fun until they started clobbering him with their wings.

When the penguins weren’t up to playing games, Igloo enjoyed yanking the big gray Weddell seals’ tails — that is, until Byrd reprimanded him. But that didn’t stop Igloo — from then on he always made sure no one was watching.

On Wednesday, January 30, the day came to unload the fuselage of Byrd’s big Ford airplane, Igloo was on board the City, keeping a close eye on the activities. The City had been tied to the Bolling, which had returned with more supplies, and they were now anchored to the ice barrier that was as high as the ship’s bridge.

A crane lifted the fuselage from the ship’s hold, and it was carefully placed on the ice barrier. Soon after, the ships rocked, jolting the edge of the ice barrier. The ice barrier cracked in an explosion of sound as an avalanche of snow and ice, weighing hundreds of tons, fell into the ocean and onto both ships. The ships rolled dangerously, nearly capsizing.

Igloo slid willy-nilly across the tilted deck, only to be saved from going overboard by landing in the scupper, or drain.

But airplane mechanic Bennie Roth, who had been standing on the ice barrier, wasn’t so lucky. He fell into the icy water and he didn’t know how to swim. Sinking, he grabbed an ice floe, but it was too slippery and kept spinning. His numb hands couldn’t hold it securely. Roth cried out for help as he reached for another ice floe.

Byrd, who had been in his cabin, ran up on to the deck, wearing only a gray flannel shirt and pants over his long underwear. He ran to the rail and jumped across the wide gap onto the Bolling. He scanned the ice-filled water for Roth.

“It seemed impossible to me that he could continue to hold on to that spinning ice,” said Byrd.

His only thought was that he was responsible for Roth’s life. Byrd knew he could reach him, and, without hesitating, Byrd plunged into the icy water to rescue Roth. But ice had floated between Byrd and Roth, blocking the way.

Byrd’s entire body was immediately stiff and numb. The water was too cold to swim in and his legs were nearly immobile. Soon Byrd, too, was fighting to stay alive.

Roth was getting tired, struggling to keep his head above the water. His clothes were weighing him down, but he had managed to grab ahold of two ice floes, one under each arm. His clothes and hands were frozen fast to them. Stunned, he remained calm, but he shouted out that he couldn’t hold on much longer.

A lifeboat was hurriedly dropped down ten feet into the water. As they paddled out to look for Roth, they came upon Byrd.

“Don’t mind me,” said Byrd. “I am all right. Go after Roth. He can’t swim.”

Byrd turned away and slowly swam toward the ship.

The rescue boat was having a hard time finding Roth. The sun was shining too brightly in their eyes. Luckily, the men on the ice barrier could see him, and they shouted and pointed. Finally the boat reached Roth. They pulled him into the boat. His body was so numb he landed in the boat face-first. They helped him sit up and wrapped him in blankets.

“I wasn’t cold all over until I got out of the water,” said Roth. “But then I couldn’t move.”

While the rescue boat made its way back, Byrd was close enough to the ship that a rope was dropped. He reached for it with his frozen hands and clung to it with all his might. The crew slowly pulled him up to the deck.

“Have they got Roth?” asked Byrd.

“Yes, he is all right.”

“Thank God,” said Byrd.

He and Roth were taken to the engine room to warm up, and it wasn’t long after that Byrd was back on the deck overseeing the unloading of the supplies. The crew continued to work around the clock in subzero temperatures, brutal winds, and fierce snowstorms that were typical in the Antarctic. A few days later, all of the supplies were unloaded, and the ships set sail on February 22, leaving Byrd, Igloo, and forty-one men behind for the long winter ahead.

It was twenty-nine degrees below zero and time to move to Little America. Igloo had never been there before, but the sled dogs, who were busy pulling Igloo on the sled over the bay ice and around a cape, knew the way by heart. In an hour and a half, Igloo arrived and was ready to explore.

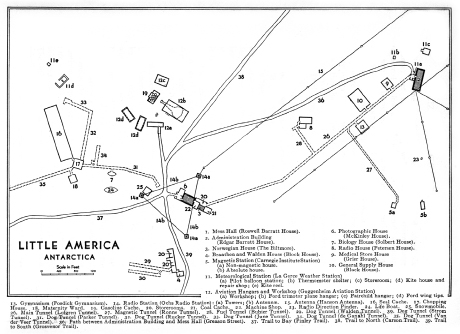

On the surface, there wasn’t much to see of Little America, with the exception of the three radio towers with blinking lights and the stovepipes and ventilators. The rest of it was buried under the snow to help insulate against the cold.

Building Little America was one of the hardest jobs the crew undertook. Using shovels, the men dug down eight feet into concrete-hard ice. The uncomplaining carpenter, Chips Gould, who had been to the North Pole with Byrd, had to warm up the nails before hammering them into the orange prefab houses, otherwise the nails would break.

They built the Administration Building, the Mess Hall, and the Norwegian House (so named because the houses were from Norway). There was also a machine shop that housed the engine to supply electricity for the radio.

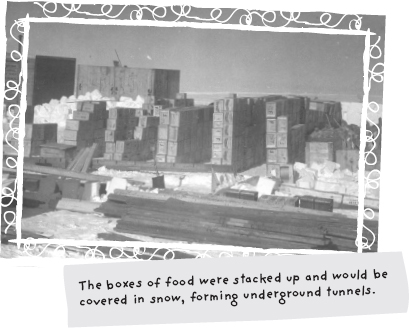

The buildings were connected by a series of underground snow tunnels to keep the men out of the fierce blizzards and eliminate the possibility of them getting lost. The upper walls of the snow tunnels were lined with wooden crates of food and supplies. They were very dark and narrow, barely wide enough for two people to walk side by side.

One snow tunnel in particular captured Igloo’s interest — it was the one called Dog Town. Inside this tunnel there were niches carved out of the sides of the wall for the sled dogs’ crates. The dogs were leashed inside and spaced far enough apart so they couldn’t fight with one another.

Byrd told Igloo to stay out of Dog Town, which was good advice. But Igloo didn’t plan to take it.