MARCH 1929, ANTARCTICA

Each morning, at the sound of reveille, Igloo would wake up in his cozy bed. It was situated at the foot of Byrd’s bunk bed in the Administration Building. Igloo’s friend, carpenter Chips Gould, had made it especially for him. Chips had lined the inside of it with soft wool shearling, and every night, before Igloo went to sleep, Byrd would cover him up in a warm blanket.

Igloo was usually an early riser, but some mornings, when the temperature in the room was below zero, it was hard for Igloo to leave the warmth of his blanket. But he didn’t want to miss breakfast. On those days, he would wait until the last minute before jumping out of his bed to accompany Byrd to the Mess Hall.

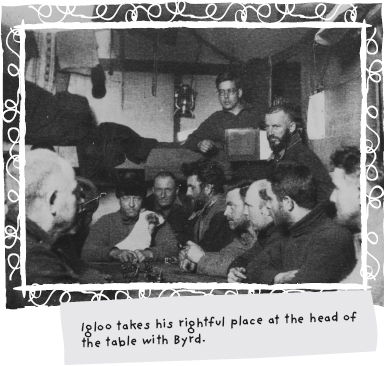

Despite the chill in his bones, Igloo always made a point of saying good morning to everyone with a wag of his tail or by leaning into their legs as he walked by. Sometimes it was while the men were busy getting dressed in their warm clothes. Other times, it was before they took their seats at the dining room table.

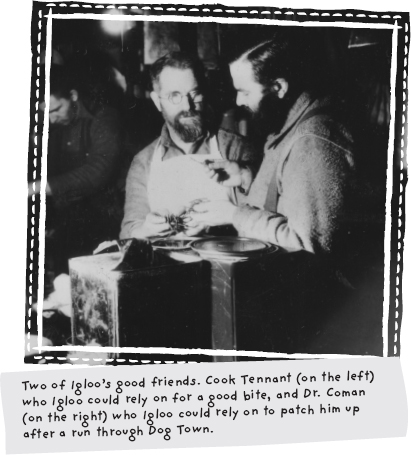

In the Mess Hall, Igloo and Byrd were greeted with the aroma of coffee wafting in the air. Cook Tennant always kept a pot of fresh coffee brewing from breakfast time until ten o’clock at night.

“Melted snow was poor drinking,” said Tennant. “So some of them drank as many as thirty cups a day of my coffee; and they seemed to think it was as good as they could want at home.”

Byrd preferred either hot tea with two lumps of sugar and cream, or hot chocolate. Igloo preferred none. But as soon as everyone was served breakfast, Igloo made his rounds, walking to each person to see what treats they would share with him from their plates.

Usually, everyone started with a bowl of hot cereal with powdered milk. Igloo looked forward to the times when Cook Tennant made bacon — it was his favorite. Sometimes Cook made fried eggs for breakfast. It was so cold the eggs were frozen in their shells, and he had to boil them first before he could fry them. And on occasion he made chicken à la king on toast. Cook Tennant also learned how to cook whale, penguin, and seal meat.

“Whale meat is good, tastes like a tender steak if you get a young one. Older ones taste fishy,” said Tennant. “We caught a young ninety-ton whale. You carefully trim all the fat layers off the back of the whale and then get down to the steak meat. With the penguins and seals I would soak the meat in salt and vinegar water for hours and then roast or boil it. Great eating, too, I tell you.”

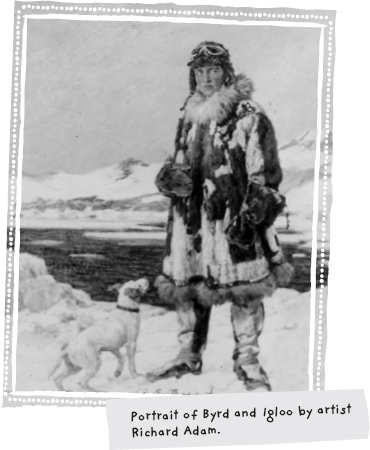

After breakfast, everyone had a lot of work to do. Along with the pilots, mechanics, cooks, and dogsled drivers, there was a team of scientists. At the time, not much was known about Antarctica, especially where Little America was situated. Although the highlight of the expedition was to see if Byrd could fly a plane to the South Pole and back, it was also a scientific expedition. The primary interest was in mapping the unknown continent and determining if it had any natural resources, such as coal.

Some of the scientists in Little America were old friends of Igloo. He had met them on his trip to the Arctic. Cyclone Haines was on the expedition studying the weather, and Malcolm Hanson was in charge of the radio.

But some were new to Igloo. Paul Siple, a twenty-one-year-old college student, Eagle Scout, and an assistant Scout master, was chosen out of thousands of Boy Scouts applicants to accompany Byrd to the Antarctic. Siple was studying the biology of penguins and seals.

The chief scientist on the expedition, and the second in command to Byrd, was the good-natured Larry Gould (who was not related to Chips Gould). Gould was a professor of geology, and he was there to study the glaciers and rocks.

Shortly after arriving in the Antarctic, Byrd had given his airplanes a test run in the cold weather and began surveying and mapping the Antarctic. Aerial photographer, Captain Ashley McKinley, who had the rare distinction of being a pilot in all three classes of aircraft — balloons, dirigibles, and airplanes — brought his fifty- pound camera on board and took photos out the window. On Byrd’s first flight, the Rockefeller Mountains were discovered. Byrd named them after John D. Rockefeller, Jr., because from the beginning he had always had faith in Byrd and helped fund Byrd’s expedition.

Professor Gould couldn’t wait to examine the rocks from the Rockefeller Mountains, especially since no one had ever seen them before. The rocks could unearth secrets about the Antarctic, such as whether any plants or animals had ever lived there.

So in early March, when it was the beginning of fall in Antarctica, Professor Gould asked if he could take a team to Rockefeller Mountains, 125 miles east of Little America, to do some geological work. Byrd was reluctant to let them go.

“Poor Larry,” Byrd wrote in his diary. “He has been compelled to dull his geological hammer on the ends of boxes while the rocks in the Rockefellers fairly cried out for investigation. Such a journey would be very important, but, frankly I am not eager to see him undertake it at this advanced period with winter so near. The weather has been stormy and cold, and I am not sure the flight can be made without considerable risk.”

But every morning Professor Gould would look at the sky and ask Cyclone Haines about the weather report. The outlook was always stormy, and Gould would rib Cyclone about his lack of skills in controlling the weather. Still, Gould was hopeful, and every day he would pack some equipment while waiting for a good weather report.

It finally came. Cyclone said there were good weather conditions for flying, and Byrd agreed to let Gould go. Bernt Balchen, who piloted Byrd’s transatlantic flight, was piloting the single-engine Fokker plane, and the square-headed Harold June, whose blue eyes twinkled whenever he laughed — which was often — was operating the radio.

With his bags already packed with his two prized geology hammers, Gould had a big smile on his face as he carried them to the plane. When Byrd watched their plane take flight, he had misgivings, until he received his first radio message from Gould.

“Everything fine with plane about forty miles from base headed towards Mts.,” the message read.

At dinnertime, Byrd received another message that they had landed safely. He was relieved for the time being. That is, until a week later. That’s when Byrd stopped hearing from them altogether. Every hour Malcolm Hanson tried to radio Gould. There was no reply. A terrible thought crept into everyone’s mind — the plane had crashed and Gould, Balchen, and June were dead.

“I should never have let them go,” said Byrd. “I knew I shouldn’t at this time of year, but it seemed necessary. I shall never forgive myself if anything happens to him.”

Igloo stuck close by, sitting on Byrd’s lap, while Byrd tried to figure out how to send a rescue team for them without getting anyone killed in the process. Treacherous weather plagued Little America, making a rescue by plane or dogsled nearly impossible. Making matters worse, Byrd wasn’t sure of their exact location since Larry hadn’t radioed in to tell them.

As each day passed, blizzards dumped snow on Little America, reminding them that the long, dark winter nights were quickly approaching. For the next several days, Byrd continued to ask Cyclone for the weather report. Finally, on March 19, five days after they lost contact with Gould, Cyclone predicted better weather.

“Frankly, I consider a takeoff dangerous,” said Cyclone. “But it may be the best chance you will have … about one chance in three, I should say, that you will find good weather all the way…. You can’t tell what this weather will do, anyway.”

Byrd figured as long as there was a chance, no matter how slim, he would take it because it might be his only chance for a rescue. They warmed the motors of the Fairchild airplane, and Dean Smith, an airmail pilot who had plenty of experience flying in bad weather, was at the controls. Byrd would navigate and Malcolm Hanson would operate the radio.

The plane took off down a bumpy, snowy runway. It finally lifted off and headed toward the Rockefeller Mountains.

After Byrd left, Igloo was inconsolable. And just when he thought his troubles could not get any worse, they did. When Igloo went into his room, he found Holly, a grouchy sled dog with a quick temper, lying down on his specially made bed. And to top it off, she was there with six new puppies.

Igloo was furious. But Holly glared at him and bared her fangs. Igloo promptly ran out of his room. He was so distraught that he wandered aimlessly through Little America, trying to collect himself. Finally, he ran for help. He alerted Cook Tennant and Captain McKinley, barking and nipping at their pant legs, trying to get them to come take a look.

Captain McKinley followed Igloo to his room, and he immediately understood Igloo’s dilemma. McKinley very carefully persuaded Holly to leave Igloo’s bed and return to her kennel with her pups. After much coaxing, she finally complied, moving out of Igloo’s bed, at least for now. She wasn’t about to let Igloo have the final say on the matter.

In the meantime, the rescue plane had returned. But Byrd wasn’t on it. Neither was Larry Gould nor Malcolm Hanson. They were forced to stay behind because the load was too heavy for the plane. But Dean Smith, Bernt Balchen, and Harold June were safely back, and everyone wanted to know what had happened.

Soon after Gould, Balchen, and June had reached the foot of the Rockefeller Mountains, they had tied down their plane and set up a tent. At first, the weather was calm, allowing Gould to collect some rock specimens, but then the wind started to pick up.

“The next morning the tent was flapping in the wind, the sides snapping like reports in a gun,” said June. “There was a tiny hole near the head of my sleeping bag and I peeked out at the plane…. I rubbed my eyes and looked again. I’m darned if the propeller wasn’t turning over despite the cold which must have made the oil stiff.”

They quickly got out of their sleeping bags and ran to the plane, trying desperately for hours to anchor it.

“Larry [Gould] and I were holding the left wing down with lines … while Bernt dug snow blocks and piled them,” said June.

But it was futile. It was soon a hurricane force wind, and they ran to their tent to take cover while the wind ripped the plane apart.

“How it blew,” said June. “I never heard such a sound. When it stopped it was so quiet that it hurt. It will linger a long time in my memory. I can hear that wind and feel the flying blocks of snow hit me yet.”

After the storm wrecked their plane, the weather improved somewhat, with temperatures reaching a high of thirty-two degrees above zero. It was difficult for them to sit and wait, but they were concerned if they tried to walk back, no one would ever find them on the vast snowy desert. On the day when they finally heard the rescue plane, they grabbed some smoke bombs and ignited them.

In the rescue plane overhead, Smith tapped Byrd’s arm and pointed out the window. Byrd could see a column of smoke and a flash of light.

“The first thought that came to my head was: Thank God, at least one of them is alive,” said Byrd.

Balchen and June had placed flags on the snow to indicate where Smith should land the plane. It wasn’t easy. The terrain was rough, and they landed with a thud and a bounce. When Byrd got out of the plane, he carried his sleeping bag to one side, knelt down, and prayed. He thanked God that everyone was alive.

“I knew he would come when it was possible,” said Gould. “He did not say a word about the loss of the plane. No one who has not experienced it can appreciate his sense of fairness and justice, his magnanimous and generous consideration for others.”

Back at Little America bad weather had again delayed a second flight to the Rockefeller Mountains to pick up Byrd, Gould, and Hanson. It was an anxious time for Igloo. If a plane couldn’t fly to pick Byrd up, then he and the others would have to walk back to Little America, and that would take at least three weeks — if they made it back at all. And to top it off, Holly kept making her way back into Igloo’s room, trying to commandeer his bed for her puppies.

It was two more days of worry for Igloo before the weather cleared and Byrd made it back to Little America. The night Byrd finally returned, he found Igloo sleeping fitfully in his specially made bed, with his nose over the side of his box and a look of utter disgust on his face. Igloo couldn’t stand the lingering scent of Holly. And Holly was relentless, coming back into Igloo’s bed with her puppies whenever the opportunity presented itself, which was more often than Igloo could bear to think about.

With Byrd back, he was able to remedy Igloo’s problem. Each time Holly came into the room, Byrd always took her and her pups back to her kennel. He finally moved Holly’s kennel next to the door of the Administration Building, which she eventually accepted as her new home. In the end, the rescue mission had been a close call for everyone at Little America — dogs and humans alike.

Just when Igloo thought he’d made himself clear on the subject — no dogs allowed in the Administration Building except him — Spy arrived. It happened early one morning when the temperature was forty below zero: so cold a person can hear the crackling sound of his breath freezing. Byrd found Spy shivering in his crate in Dog Town and nearly dead from the cold. The hard work of hauling the heavy sled had taken a toll on him. Spy was so cold he could barely walk, and one of his paws was so sore and lame, he dragged it across the ground.

Byrd brought the friendly lead dog into the Administration Building, and Spy — with his eyes half-closed — sat down stiffly by the warm stove. He let out a mournful groan from the pain.

Spy’s dog driver, Norman Vaughan, who loved Spy, was worried that Spy was in too much pain and should be put down.

“Let’s give him a chance,” said Byrd. “He has earned it and perhaps he can have a few comfortable months more.”

Byrd placed some canvas bags in a corner of his room, far away from Igloo’s bed. Even so, Igloo was furious about this new arrangement, and he barked unhappily at Spy.

“The only available space in the camp at the time was in my room,” said Byrd. “And old Spy lay there for two days, much to the disgust of Igloo who attacked him whenever my back was turned.”

When Spy gained some strength and started to hold out his paw to be shaken, Byrd took him outside for a walk, hoping the exercise would help. Spy spotted his brothers, Moody and Watch, hooked to a sled and limped over to see them. Moody and Watch were lying down with their legs stretched out on the snow. Spy sat down between them. His brothers licked his face and his sore paw. Watch gently pushed his head into Spy’s while all three cuddled, keeping Spy warm.

Then the dog driver cracked his whip and yelled “Yake!” for straight ahead. The dogs stood up and took off running. Spy gathered all of his strength and ran as fast as he could, running alongside the team and trying to find his place as their lead.

“It was one of the most beautiful things I have ever seen, and for a penny I would pluck a moral from it,” said Byrd. “The whole camp stopped working at the sight, and watched with wonder how Moody and Watch nuzzled the veteran, and laid their paws on him in a most extraordinary gesture. That these wild and untrammeled animals should be capable of harboring so deep and lasting sentiment was beyond understanding.”

Igloo, on the other hand, had reached his boiling point with Spy. In a show of appreciation to Byrd, Spy tried to climb up onto his lap. Igloo wasn’t about to let that happen, and with all of his strength, Igloo heaved Spy from Byrd’s lap.

Spy didn’t fight back. Instead, he gave Igloo a hangdog look and walked out of the Administration Building, never to return. Spy went back to his brothers in Dog Town — where, as far as Igloo was concerned, he belonged.

Although Spy never worked as a sled dog again, he recovered. And every time Igloo would see him, Igloo had the decency to act contrite. But Spy didn’t hold it against him.

On April 17, 1929, the sun disappeared and darkness fell on Little America for the next four months. Below ground, dim lights glowed inside Little America, and Byrd’s expedition was faced with the challenge of keeping busy while being cooped up.

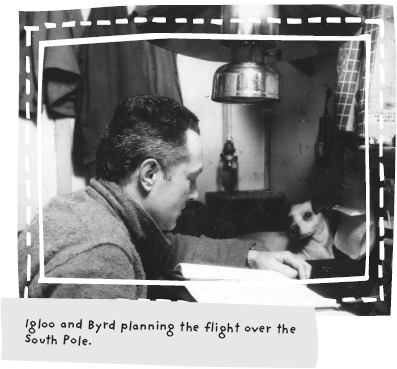

Byrd was usually sitting at his desk, chewing on the tip of his pencil, and working out the problems with flying in the Antarctic. The main one was figuring out how to carry four men plus all of the food, fuel, and equipment — especially when they flew over the enormous mountains. He had to consider all possibilities and make contingency plans if they crashed.

As Byrd worked, Igloo was faced with the challenge of keeping warm. Like the sled dogs, Igloo grew a thicker coat of fur. He even had an extra clump on the end of his tail, making it look like a toothbrush. There were stoves to warm the rooms, but heat rises, and there was a fifty-degree difference between the temperature at the floor of the rooms in Little America and at the ceiling. Ice formed on the floor, and everyone’s feet were cold, especially Igloo’s. To keep their feet and legs warm, the men wore their fur pants and boots. Igloo learned to lift his paws up one after the other, as if he were walking on hot coals, to try to keep them warm.

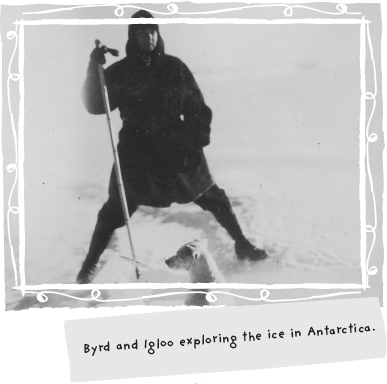

Despite the cold and darkness, Byrd and Igloo continued their daily walks outside. But during the walks, Igloo would sometimes suddenly lie down. He would hold up a paw and cry out, refusing to budge until Byrd picked him up and rubbed his frozen paw. Once it was warmed up, Igloo would jump down and continue walking. That is, until his paw got cold again.

When the temperature dipped to thirty degrees below zero, it was just too cold for Igloo outdoors. Even though it was one of his most favorite things to do, Igloo just couldn’t bring himself to go outside, especially if the wind was blowing.

Instead, Igloo preferred to play with his new favorite toy — the rubber ball that squeaked like a cat. For Igloo, the trick was to find someone to play ball with him. Byrd played at least three times a day, by hiding it in various spots around the Administration Building so Igloo could look gleefully around for it. But sometimes Byrd was too busy.

During those times, Igloo would glance stealthily around to see if anyone happened to notice the ball. If no one reached for it, Igloo would push it with his nose, rolling it toward anyone nearby. As someone reached for it, Igloo would pounce on the ball, making it squeak, and he would let out a growl before dashing off, wagging his tail happily. But if no one was willing to play, Igloo squeaked it continually until someone finally grabbed it — sometimes just to stop the noise.

On occasion Cook Tennant gave Igloo a bone, and Igloo would set to work finding the perfect place to bury it. Since the ground was frozen, he had to find alternative places to hide his treasure. Sometimes Igloo would bury it under his bed or under a rug. But one of the best spots he found was hiding it at the bottom of Byrd’s sleeping bag.

Nevertheless, on the days when Igloo tired of these games or when everyone was too busy, he sometimes played with the pack of twenty wild sled dog puppies — new friends that Igloo tolerated and usually ran into on his way to the Mess Hall.

“Literally, they ran wild,” said Byrd. “They could not be captured, but prowled the camp, feeding on scraps of food that were put out for them, enduring the lowest temperatures without visible discomfort.”

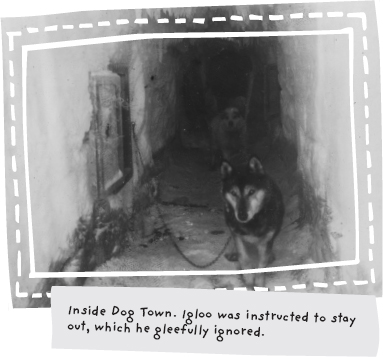

Igloo was always looking for a way to sneak inside Dog Town. The tunnel was dark — with the exception of the dogs’ glowing eyes — and it echoed with barks and howls, and had a pungent smell of dogs and raw seal meat.

A run through Dog Town was always a death-defying experience — even for the men. One time when Chips Gould went there to repair a gate, one of the pups ran off with his lantern. In the darkness, Gould got lost and he feared a run-in with Oulie, the meanest dog in Dog Town. Luckily, Gould ran into Birch, one of the sweetest dogs. Birch guided Gould safely out of the dark tunnel and to the Mess Hall, where Gould gave Birch a whole leg of lamb in appreciation.

Igloo knew that if he ran through Dog Town, he had to be quick, timing it just right so the dogs, who were chained, couldn’t catch him. When Igloo streaked by, total chaos followed, with the dogs trying to bite and slash him with their claws. A run through Dog Town usually ended with Igloo lying on the table in the Mess Hall with his good friend, Doc Coman, patching him up with stitches. Even so, this never stopped Igloo. Like Byrd, it was the danger that thrilled him.

“He had long since got over the shock they first gave him during the trip South on the City of New York. He feared not even the biggest dog among them,” said Byrd. “No doubt, he believed he was a great fighter because we saved his life so often. He was even condescending in his attitude, especially toward the pups, although his life was really in great danger. We had to watch him very carefully, because when he was allowed to run loose he invariably made for Dog Town. Almost always he returned in need of medical attention.”

One day a terrible noise was coming from Dog Town. It sounded like a dog was dying — yelping and crying for help. The men realized the cries were coming from Igloo, and they were worried that he was half-dead from a fight.

Someone ran into the darkened tunnel with a lantern and in the shadows found Igloo sitting down with a paw outstretched. Uninjured, Igloo was in pain from the cold. He was howling for someone — preferably Byrd — to warm his paws.

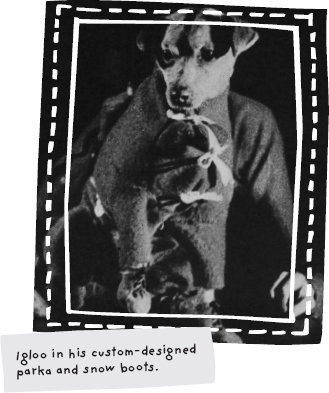

When Byrd heard the news, he did one better for Igloo. Byrd consulted Martin Ronne, who fired up his sewing machine and made Igloo his very own snowsuit and boots. The parka and pants were made of camel’s-hair wool, and the boots, which laced up, were lined with wool and stuffed with senna grass to keep his feet dry.

Igloo looked adorable in his new snowsuit and boots. And the men sitting around the table laughed with delight. Igloo, on the other hand, was absolutely humiliated by the idea of wearing a snowsuit and boots. He sat frozen on the table, unwilling to move.

“Come, come, Igloo!” said Byrd. “You can’t feel quite that bad. Walk around a bit. It’s really a perfect fit.”

Byrd gave Igloo a reassuring nudge, and Igloo walked stiff legged around the table, receiving pats of encouragement from Byrd and the men. Igloo wagged his tail hesitantly.

The snowsuit and boots kept Igloo warm and snug, but Igloo soon found out that the snowsuit and boots also made him a walking target. The first time the pups saw Igloo in his new snowsuit and boots, they could barely contain themselves. They were falling all over one another as each one tried to reach Igloo first. Immediately, they sunk their razor-sharp teeth into Igloo’s parka and yanked him in all directions.

Needless to say, Igloo was hopping mad. At first he tried to control his temper. Igloo never liked to look childish in front of Byrd. But when the pups ripped holes in his new warm coat, Igloo wasn’t going to stand for it.

He turned around and faced the pack of pups. With his brown ears flat against his head, Igloo charged toward them, striking them like a bowling ball against the pins. The puppies rolled and were stunned — most of them took off running. But a few remained, and Igloo took them on in a dogfight. Byrd quickly broke it up.

Igloo continued his walk with Byrd. The pups walked behind them, keeping a safe distance from Igloo, who was still fuming because his parka now looked ragged — its epaulets were torn and there was a large hole in the back.

But Ronne fixed the snowsuit for Igloo. He sewed some patches on the parka, and it was almost as good as new. The pups never dared to rip it again, and Igloo learned to like his snowsuit and boots. Whenever he wanted to go for a walk with Byrd, he would grab his snowsuit and drop it at Byrd’s feet.

The darkness that fell on Little America finally lifted on August 22, 1929, when the sun returned, peeking over the horizon. To mark the occasion, the expedition raised the American flag and played a bugle call on the Victrola. It was time to dig out from the harsh winter and make the final preparations for Byrd’s riskiest flight yet — to the South Pole and back.