Although spring was in the air, it was still bitterly cold in Antarctica. Fierce blizzards still plagued Little America, and the temperatures still dropped to sixty-eight degrees below zero. Even so, it was a busy time gearing up for the flight over the South Pole, which would take months of preparations.

“Everyone is at work at something — sewing parkas and socks, repairing harnesses, testing tents, relashing sledges,” Byrd wrote in his diary.

Professor Larry Gould and his geological party were planning their scientific expedition. They would be gone for three months and travel some 1,500 miles. Gould and his team were going to map and study the mountains and leave emergency food and fuel caches along the flight route for Byrd. The Supporting Party would leave beforehand to break the trail for the Geological Party. Both parties were using dogsleds. But preparing the sled dogs was proving to be more difficult than anyone expected.

“We have had a wild time with the dogs,” said Byrd. “They are so overjoyed to be aboveground once more that they have forgotten all manners and training, and run about the camp like lunatics.”

Boy Scout Paul Siple was tasked with capturing the unruly, wild pups and teaching them to pull a sled. On October 15, the day the Geological Party was leaving for a two-day preliminary test, Byrd and Igloo were there to see them off. Siple offered to take Byrd and Igloo on for the first several miles of the expedition.

“He gave me what I would conservatively describe as the wildest ride I ever had,” said Byrd.

With Holly as the lead dog and the pack of wild pups harnessed behind her, Holly took off running. The sled zoomed across the bay ice as if it were on fire. Very quickly, the pups got tangled in the harness, and the sled suddenly overturned.

While Byrd and Siple tried to straighten out the lines, Holly refused to stand still, making their job even more difficult. Finally, they took off again. But the pups once again got tangled. As Byrd started to get off the sled, Holly suddenly jerked forward. The supplies flew off the sled — along with Byrd and Igloo — while Holly and the pups took off sprinting, not stopping for the next half mile.

“I was fond of Holly,” said Byrd. “But she was mightily in wrong for the moment.”

After that, the pups and Holly were on their very best behavior and did a good job, even overtaking some of the bigger teams of sled dogs. After two hours, Byrd and Igloo bade farewell to the Geological Party. They watched the other dogsled teams run up the slope and disappear behind it, only to see them go up another slope, then disappear again.

When the dogs and sleds were no longer in their line of sight, Byrd and Igloo returned to their sled only to find that the pups had chewed up their harnesses and were once again running wild. Byrd and Igloo hitched a ride on a different sled back to Little America.

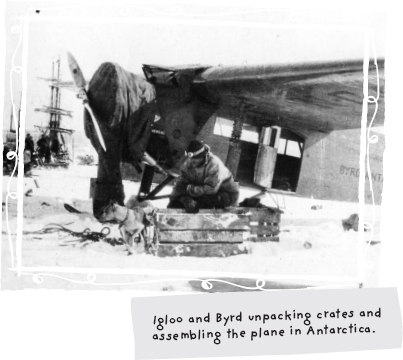

Two weeks later, Byrd’s Ford airplane, the Floyd Bennett, was taken out of its ice hangar, a ten-foot hole with walls made from blocks of rock-hard snow and ice. It was covered over with a tarp and drifted snow. Byrd’s crew shoveled away the snow and sliced away the walls. The plane was in good shape, having survived the treacherous weather, but it needed some work before it would be ready to fly.

The plane was in pieces and had to be reassembled. The wings were wet and had to be dried using blowtorches before being reattached, the fuel lines needed to be cleaned out, and the mechanics worked on the three engines, making sure everything was just right.

Igloo took his job of supporting Byrd very seriously, and he always stuck close by. He didn’t want to be left behind when Byrd took flight for the South Pole. To make sure this didn’t happen, Igloo had a plan.

In the meantime, Byrd was waiting for a good weather report. Sunshine was absolutely essential for a successful flight.

“Flying down here with a cloud-covered sky is like flying in a world that has turned to milk,” said Byrd. “There is nothing to check on. Horizons disappear and there is no way to tell where the snow begins, how rough the surface is, nor even how high we are above it…. When the course goes over mountains whose peaks tower higher than the plane can fly, good visibility is required to get between the peaks over the glaciers.”

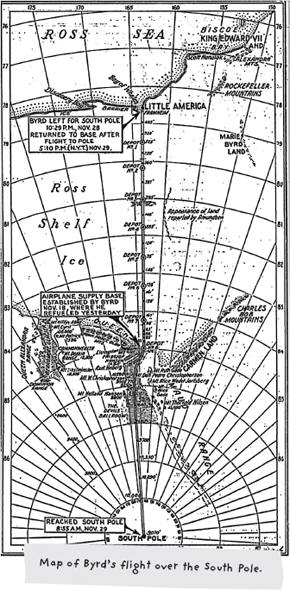

Finally, on Thanksgiving Day, November 28, 1929, Cyclone Haines predicted good weather. It was time for Byrd to take flight.

The plane was loaded with sleeping bags, fuel, oil, tents, clothing, sacks of food, a small sled, stoves, and photographic equipment. Each item was carefully weighed to make sure the plane did not exceed 15,000 pounds. If the plane was too heavy, it wouldn’t be able to fly over the mountains.

“For many months our minds had been concentrated on the knotty problem of getting over this rampart…. We made very careful tests with the plane and had checked and rechecked our figures for weeks … there must be no mistake about our load,” said Byrd. “Every ounce of food, every piece of clothing, everything that went into that plane, including ourselves, had to be weighed carefully.”

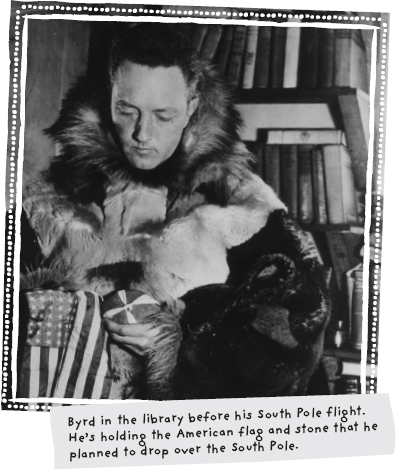

The last thing Byrd put on the plane was an American flag weighted with a stone from Floyd Bennett’s grave. Byrd was going to drop it on the South Pole.

“It had been the three of us — Bennett, Balchen, and myself — who had set out on this job two years ago, and the three of us would be together at the finish, for we knew that Floyd Bennett’s spirit flew with us,” said Byrd. “He had selected the Ford plane, prepared it and flown it, and had helped with our early plans, so that his genius and his friendship were with us helping us to reach our goal.”

Dressed in their polar fur suits, Byrd, Balchen, Harold June, and Ashley McKinley were ready to attempt the first flight over the South Pole. Before taking off, Byrd made a final, last-minute check of the airplane. When he reached the back of the plane, he was surprised to discover Igloo comfortably settled in and ready to go.

Igloo was greatly disappointed when Byrd removed him from the plane. His cunning plan to be a stowaway was foiled.

“Igloo didn’t go along in the plane…. That wouldn’t have been right,” said Byrd. “In case of an accident what would happen to a dog?”

From the snowy runway, Igloo stood among the men and watched the plane disappear over the horizon. Inside the plane, Balchen was busy at the controls while June listened intently to the roar of the motors. He was monitoring the plane’s fuel consumption, making sure they didn’t run out. Throughout the flight, McKinley never stopped snapping photos. He was creating an aerial map of their flight, the first of its kind, and it was of great geographical value.

Byrd was all over the plane, shifting his position so he could take observations to navigate, maintaining their course with his dependable sun compass and drift indicator. It wasn’t easy to move around in the plane. There were piles of supplies smack in the middle of the fuselage. The smell from the gasoline fumes and the rarefied air made it hard to breathe. And there was a cold wind that blew through the plane, making them glad they were wearing their furs. Even so, for the first few hours, they were able to enjoy the scenery as they headed toward the Queen Maud Range.

“Flying over this mysterious Barrier never loses its fascination … Great white glaciers flowed into the Barrier … alpine snow-covered peaks towering high over the Barrier that glistened like fire from the sun’s reflection so that they looked like great volcanoes in eruption,” said Byrd.

But soon the perilous mountain peaks were directly ahead of them, and just beyond, on the 10,000-foot plateau, was the South Pole. Byrd had a do-or-die decision to make — which route to take — flying over Axel Heiberg Glacier or Liv Glacier.

They both looked dangerous — with their narrow passes sandwiched between gigantic peaks. If the plane was too heavy, they would crash right into the mountains.

“I was by no means certain which glacier I should choose for the ascent,” said Byrd.

Byrd went forward and stood behind Balchen. He looked out the window and studied the peaks. Byrd knew that the Axel Heiberg Glacier was 10,500-feet high. But he didn’t know if the pass between the peaks was too narrow. If they were too narrow, the air currents could push the heavily loaded plane to the ground.

And nothing was known about Liv Glacier. From where Byrd was standing, the pass looked wide enough. But he couldn’t see if there were mountains behind it. And if there were mountains, he didn’t know if they would be able to fly over them.

“Doubtless, a flip of the coin would have served us well,” said Byrd.

Byrd chose Liv Glacier. The pass looked wider than and not as high as Axel Heiberg Glacier. Still, it was a gamble.

“Once we entered the pass,” said Byrd, “there would be no retreat. It offered no room for turn. If power was lost momentarily or if the air became excessively rough, we could only go ahead, or down. We had to climb, and there was only one way in which we could climb.”

Balchen flew the plane toward Liv Glacier and approached it with caution and confidence. The plane’s wings shook from the changing air pressure, and they hit a patch of turbulence. The violence of the turbulence forced Balchen to turn the plane slightly to the left, and soon they were caught in heavy downdrafts.

As the plane approached the glacier’s peak, the plane was too low — it was carrying too much weight. They were going to crash.

Balchen was gesturing wildly, trying to be heard over the roar of the engines.

“Overboard! Overboard!”

June stood with his hand on the dump valve of the main fuel tank. If he pulled it, six hundred gallons of gasoline would be unloaded. Byrd gestured to wait. He had to decide — food or fuel?

“If gasoline, I thought, we might as well stop there and turn back,” said Byrd. “We could never get back to the base from the Pole. If food, the lives of all us would be jeopardized in the event of a forced landing.”

It only took a moment for Byrd to decide. McKinley had already moved one of the 125-pound bags of food to the trap door. One bag was one month’s supply of food for four men.

“A bag of food overboard,” Byrd yelled to June.

McKinley was standing by the trapdoor, and June signaled to throw it out.

“Shall I do it, Commander?” McKinley asked Byrd.

Byrd nodded his head. They watched the brown bag fall, spinning to the ground. The plane started to gain altitude. Balchen looked back and smiled. He moved the plane to the right, and flew over the lowest part of the pass.

But, once again, the plane hit turbulence, knocking them around “like a cork in a washtub.” They could barely stay on their feet. Very slowly, the plane inched up. Even so, the wheel suddenly turned loosely in Balchen’s hand.

“Quick! Dump more!” Balchen shouted over the din of the engines.

Byrd pointed to a bag of food. McKinley opened the trap door, the freezing air burning his face, and he dumped another bag. It was their last chance.

“We could not let any more food go,” said Byrd. “Nor could we dump gasoline and have any reserve supply left for reaching the Pole. There was nothing more to dump. We must make it.”

They watched the bag of food shatter soundlessly against the glacier below them. Suddenly, the plane lifted higher into the air. And when they reached the towering pass, they flew over it with about three hundred feet to spare. The usually quiet Balchen let out a shout of joy.

After ten hours of flying, at 1:14 a.m., Byrd passed a note to June. It read, “My calculations indicate we have reached the vicinity of the South Pole. Flying high for survey. Soon turn north.”

Byrd opened the trapdoor and dropped the American flag and a piece of stone from Floyd Bennett’s grave. Byrd stood and they “saluted the spirit of our gallant comrade and our country’s flag.”

When June radioed the news to Little America from the plane, everyone cheered. Igloo joined in by hopping up onto the Mess Hall table and barking with all his might. And nine hours later, Igloo was the first to hear the hum of the airplane on its return. He stood on the runway, running back and forth excitedly as the plane landed. The men tossed their hats in the air and cheered. And Igloo was one of the first to greet Byrd when he got off the plane, running alongside him, jumping up, and patting Byrd’s leg.

Everyone hurried into the Mess Hall to have some hot drinks from Cook Tennant’s galley. There was a lot to celebrate on Byrd and Igloo’s Antarctic adventure. And they would soon find out that the celebration was just beginning.