Chapter 6

Getting Tough, Making Money and Taking Country

In This Chapter

Making the punishment of convicts more systematic (and more terror-inspiring)

Making the punishment of convicts more systematic (and more terror-inspiring)

Controlling the convicts and the press: Governor Darling

Controlling the convicts and the press: Governor Darling

Fighting bushrangers and Tasmanian Aborigines: Governor Arthur

Fighting bushrangers and Tasmanian Aborigines: Governor Arthur

Entering boom times with wool and grabbing land

Entering boom times with wool and grabbing land

The 1820s and 1830s were a period of massive territorial expansion in European settlement in Australia. Australia’s ‘fertile crescent’ — the stretch of land that goes in a curve from southern Queensland, continues through modern NSW and Victoria, and ends in the region surrounding Adelaide in South Australia — was occupied in this period, changing everything.

Meanwhile a massive penal reform was being implemented by the Governors Ralph Darling in NSW and George Arthur in Van Diemen’s Land (modern-day Tasmania). The new instructions from Britain were to get tough and to systematise, and that’s exactly what Darling and Arthur set about doing.

By the late 1830s, demand for wool was going through the roof as Britain’s industrial revolution kicked into gear, and factories and wool mills began producing commodities at a greater rate and for cheaper prices than had ever been seen before. Australia, with newly opened up grasslands and pasturage, was perfectly placed to take advantage of this. Investors with capital in London, Edinburgh and Manchester began channelling funds into Australian properties.

In this chapter, I cover Britain’s attempts to make the punishment of convicts in Australia more systematic and consistent (and more of a punishment). I also look at the impact of the developing wool trade on the riches of the colony and on the settlement of newly ‘acquired’ land (and British attempts to control this frantic settlement as well).

Revamping the Convict System

In 1819 Earl Bathurst of the Colonial Office in London sent Commissioner John Thomas Bigge (ex-chief justice of Trinidad) to Australia to report on the state of affairs in the Antipodes. By this time, word had made its way back to Britain that life in New South Wales wasn’t too bad, and that the new colony could actually be a land of second chances — if you played your (sometimes randomly dealt) cards right. Because of this, convicted criminals began requesting transportation (refer to Chapter 5 for more on this, and for more on Commissioner Bigge’s trip Down Under). So, as well as a rundown on what was happening, Bathurst wanted ideas to make the punishment of transportation to be a real deterrence again — and Bigge delivered.

Over the next two decades a new system was implemented, one that tried to eliminate the perks, inconsistencies and arbitrariness that had been a feature of the previous form of transportation. Being sentenced to transportation would again evoke fear in the hearts of would-be criminals, and the system would have a system — convicts would be rewarded for good behaviour and signs of reformation, and punished for further crimes or bad behaviour.

At the Colonial Office, Bathurst also starting offering enticements (in the form of land grants and free convict labour) to free settlers, hoping that an influx of immigrants would tip the moral scales of the colony into a more ‘respectable’ tone.

To make sure his new regime was implemented effectively, Bathurst then sent out his enforcers — Governors Darling and Arthur.

Putting the terror back into the system . . . and the system back into the terror

Under Bathurst, and based on Bigge’s recommendations, the new priority was ironing out old loopholes, freedoms and indulgences. The hope of easy money and free land should no longer be an enticement to England’s criminals.

Bigge and Bathurst’s new, more systematic, regime included:

No more special deals for convicts when they arrived, regardless of what sort of work they could do or what sort of connections they had. This also meant convicts would no longer be automatically assigned to their spouse (if they were already here and being assigned convicts) on arrival.

No more special deals for convicts when they arrived, regardless of what sort of work they could do or what sort of connections they had. This also meant convicts would no longer be automatically assigned to their spouse (if they were already here and being assigned convicts) on arrival.

All convicts to work for no wages.

All convicts to work for no wages.

Tickets of leave to be given out only after serving a minimum sentence, and only if the convict was well-behaved. These indulgences (established under Governor King and kind of like instant parole) would no longer be given out to save money, or as a sign of the Governor’s favour, but only as a special reward.

Tickets of leave to be given out only after serving a minimum sentence, and only if the convict was well-behaved. These indulgences (established under Governor King and kind of like instant parole) would no longer be given out to save money, or as a sign of the Governor’s favour, but only as a special reward.

When assigning convict labourers to settlers, the new free immigrant arrivals would have priority. Ex-convicts were no longer considered to be fit ‘masters’ to oversee the reform of criminals, and convicts being assigned to convicts (on ticket of leave parole) was eliminated completely. (Not using ex-convicts as convict ‘masters’ proved impossible to implement — too many of the bosses and land owners in the new colony were ex-convicts.)

When assigning convict labourers to settlers, the new free immigrant arrivals would have priority. Ex-convicts were no longer considered to be fit ‘masters’ to oversee the reform of criminals, and convicts being assigned to convicts (on ticket of leave parole) was eliminated completely. (Not using ex-convicts as convict ‘masters’ proved impossible to implement — too many of the bosses and land owners in the new colony were ex-convicts.)

New hellish punishment places to be created for those who continued to commit crimes after their arrival in Australia. This included settlements on Moreton Bay, Port Arthur, Macquarie Harbour and Norfolk Island.

New hellish punishment places to be created for those who continued to commit crimes after their arrival in Australia. This included settlements on Moreton Bay, Port Arthur, Macquarie Harbour and Norfolk Island.

Under these changes, transportation became a thing to legitimately fear again.

Bringing in the settlers

During the 1820s, there was a new emphasis at the Colonial Office on encouraging wealthy free settlers to emigrate to Australia. This was meant to achieve two things. Firstly, they would help ‘grow’ the pastoral and agricultural economy, giving NSW an export industry which would help it become less of a drag on the British Treasury. Secondly, they would provide the right ‘tone’ of respectability to help balance the regrettable low class and unruly nature of NSW society.

Workers would be provided by transportation, but they weren’t encouraged to later become established employers or successful businessmen or landowners. The free settlers arriving with ample capital received the lion’s share of land grants and the convict labour, rather than the convicts and emancipists (ex-convicts) or their children, who were known as ‘the native born’.

Bringing in the enforcers

A lot of Bathurst’s changes were first announced while Governor Macquarie’s replacement, Thomas Brisbane, was in charge of NSW and Lieutenant-Governor Sorrell was in charge of Van Diemen’s Land. But Britain remained unhappy with the convict system — it still wasn’t inspiring enough dread. Two tough-minded military officers were chosen to come out as replacements — Ralph Darling for NSW and George Arthur for Van Diemen’s Land.

Darling and Arthur had both served in the Napoleonic Wars, and both had proved themselves as not just tough officers but extremely able administrators — order, efficiency, discipline and a liking for absolute control featured prominently on their respective CVs. Both men took over the changes that had been begun under Brisbane and Sorrell, and quickened the pace, worked hard to increase the order and — where they thought necessary — the severity.

Getting Tough Love from Darling

Ralph Darling arrived in Australia in 1825, and he came with the clear idea that a convict colony couldn’t expect to be treated like a normal free society. People who still had warm memories of the close paternal involvement taken by Governor Macquarie (and his memory was still toasted at annual dinners to mark first settlement day on 26 January) were in for a rude shock with Darling’s manner.

Darling was the new breed of officer. Cold, calm, aloof and rational, with a strong belief that British colonies should do what they were told, he worked hard at reforming the colony’s administration, the allocation of land, the quirky banking, bartering and IOU system (refer to Chapter 4) and, most of all, the convict system.

None of this was easy, partly because of practical reasons and constraints — such as administrative positions being staffed by convicts and ex-convicts, with no-one else willing or available to take their place — and partly because there was now a very entrenched belief in the colony that this place was here for more than just punishing convicts, and had other ends to serve beyond the wishes of the British government.

In the new colony, the press had more freedom than the press in Britain (and much more than Darling would like) and weren’t afraid to take advantage of this. Darling also had little interest in new requests being put forward by ex-convicts and native-born Australians for a more representative assembly and for trial by jury.

In a word, the colonials were getting uppity again, and Darling had the devil of a time trying to iron it all out.

Running into staffing issues

The practical constraints Darling found himself confronted with arose because, to implement most of the changes he wanted to make to NSW convict society, he had to try to convince the convicts themselves to help him. Before Darling arrived most of the clerks working in the civil service were convicts. This meant that most of the sensitive administration — noting down how many years a convict still had to serve for instance, or how much land should be granted to individuals — was in the hands of men whose professional integrity wasn’t exactly above reproach.

Instances of people bribing officials to get a convict’s sentence surreptitiously shortened as the paperwork went from hand to filing cabinet occurred so often that by the time Darling arrived there were even standard rates — so much for getting your sentence shortened from life to 14 years, so much for halving it from 14 to 7, and so on.

Darling naturally wanted to eliminate corruption and remove convicts from administrative positions, but then found, to his annoyance, that he couldn’t — it wasn’t possible to staff the administration with free immigrants only. Convict society was being run by convicts because there was no-one else around to do the work. Darling did what he could to change the system but he also had to make do with what he had.

Going head-to-head with the press

When Darling arrived in NSW, he was aghast to find a press operating with greater freedom than in Britain — with convict journos! And ex-convict editors! In a penal colony! This he thought was crazy, especially when two newspapers — The Australian and The Monitor — began waging pubic campaigns against him, taunting and denouncing him at every opportunity. (See the sidebar ‘Two soldiers and the son of a highwayman’ for more on The Australian’s campaign against Darling, under the editorship of William Wentworth.)

Darling tried to cripple the press by imposing a stamp duty on newspapers through introducing a Newspapers Duty Bill. However, just before he had arrived, a new Legislative Council had been formed, with members to be nominated by the governor to advise him. Darling thought that because he was the governor sent by Britain and those in the Council were only there because they’d been nominated — not elected — he should have a free hand in reshaping NSW, without having to bother unduly about the rule of law. Chief Justice Francis Forbes begged to differ and overturned the bill, describing it as ‘an excessive instrument of suppression’.

Coming up against calls for representation

Darling’s clash with the press was soon used by Wentworth, as editor of The Australian, to create wider implications. According to Wentworth and his supporters, not only was Darling an ‘unjust, despotic’ governor but the whole form of government in the colony was equally unfair.

Despite the overturning of the Newspapers Duty Bill (refer to the section ‘Going head-to-head with the press’ earlier in this chapter), the Legislative Council wasn’t much more than a rubber stamp. Wentworth demanded a representative government and the right to trial by jury for everyone, a sentiment shared with varying degrees of enthusiasm by the convict and ex-convict population. This wasn’t quite radical democracy — Wentworth blithely assumed that naturally only those with property and wealth should be represented. But it was a lot more than the British Governor or the colonial Exclusives were willing to countenance.

In the early 1820s, the majority of those with wealth and property in Australia were those who had previously been convicts, and the concept of giving them effective power in a colony which the Colonial Office was still trying their best to make terrifyingly severe for would-be crims in Britain wasn’t tenable.

Putting it all down to a personality clash

Darling was picked by Bathurst to come out to Australia and be tough, and in this Darling performed exactly as asked. The problem was Bathurst’s vision for Australia as punishment and deterrent was at odds with the vision of most of the people living in the colony.

Darling wrote off his clash with Wentworth: ‘As to Young Wentworth, he is a Demagogue . . . a vulgar, ill-bred fellow . . .’ But people of import at the Colonial Office were beginning to conclude that at least half the problem might be Darling himself.

As complaints and controversies kept rolling in, James Stephen, the Permanent Under-Secretary in the Colonial Office concluded that Darling’s ‘great unpopularity’ in the colony had been caused in significant part by ‘the exercise of his authority by a severe temper and ungracious manners’. The ‘deep-rooted antipathy’ towards him meant that no peace could be had ‘so long as General Darling is Governor of NSW’. Ominous words.

After a new reformist liberal Whig administration took power in London, Darling, the stern conservative Tory, was recalled to Britain. His recall was put down to ‘misunderstandings and dissensions’ which had made his tenure in the colony untenable. Darling did his best to take it on the chin.

If he’d done wrong, Darling said, then he asked his new boss, Viscount Goderich (Bathurst’s replacement at the Colonial Office), to bear in mind the sort of material he’d been forced to work with: ‘Habitual Drunkards, filling the most important Offices, Speculators, Bankrupts and Radicals, while I (and I only state the fact) have exerted myself strenuously to promote the views of His Majesty’s Government and maintain His Majesty’s Authority.’ Deep sigh. However — ‘If it be Your Lordship’s will that I should be the Sacrifice, I must submit . . .’

Enduring Tough Times from Arthur

While Darling was doing his level-headed best to implement big changes in the way NSW was run from 1824 to 1831 (see the preceding sections for more about Darling), George Arthur was doing the same down in Van Diemen’s Land until 1836. Like Darling, Arthur was an army officer with a background in administration, and he also had an unswerving view that the colony he was administering existed for the purpose of serving British rather than local needs.

Arthur oversaw the conversion of Van Diemen’s Land to a colony completely devoted to punishment and made the recording of this punishment more systematic. He couldn’t devote all his time to the convicts, however — he also had to deal with some pesky bushrangers and work on the Aboriginal ‘problem’.

Concentrating on punishment and reform

In 1824, just as Governor Arthur was arriving, Van Diemen’s Land (known as Tasmania these days) was made a separate colony to NSW, and given a more particular purpose than what it had previously had. Rather than just a colony of free settlers and convicts, it started to become more definitively the British Empire’s chief receptacle for many of the worst criminals. Over the next three decades, Van Diemen’s Land became the place where punishment and reform of convicts became the chief preoccupation of government. Arthur was the perfect choice to attempt bringing this change about.

Arthur, even more than Ralph Darling, had almost untrammelled powers as governor of Van Diemen’s Land. Advised but not much influenced by a nominated Legislative Council, hostile to ideas of colonists having trial by jury or a representative assembly, Arthur suffered no anxiety that Van Diemen’s Land existed for any other reason than to serve as a place of punishment and reform for convicts. If this was the colony’s purpose, he figured, you couldn’t choose to settle there and then complain that it lacked a free press or other ordinary British freedoms. (Some newspaper editors argued strongly with him on that score, but they generally found themselves jailed.)

Arthur’s opinion of Van Diemen’s Land as a place of punishment and reform was fully shared by the Colonial Office. James Stephen in the Colonial Office talked of it as ‘a Colony set apart for the discipline and reformation of the scowerings [sic] of our Gaols’. The best approach to take towards such a colony was, he joked, the same as dealing with a young child — ‘Be good Children and dutiful and quarrel with us as little as you can help and we will be very tender and considerate Parents’.

Arthur was in place to make sure that the child colony stuck to its lessons while the parent nation was busy on the other side of the world.

Recording punishments in the system

From very early on Arthur started monitoring all the administration of convict life, keeping detailed records of each convict: His or her behaviour, crimes, and progression or regression under the penal system.

Under Arthur, the punishment system had a series of different grades, or rungs on the ladder:

The lowest rung, for repeat offenders who had committed further crimes upon arriving in the colony. They were sent to isolated penal settlements and subjected to rigorous punishments — hard labour, treadmill and solitary confinement.

The lowest rung, for repeat offenders who had committed further crimes upon arriving in the colony. They were sent to isolated penal settlements and subjected to rigorous punishments — hard labour, treadmill and solitary confinement.

The next rung, convicts who were assigned to government work, generally on road gangs.

The next rung, convicts who were assigned to government work, generally on road gangs.

The third rung, convicts who were assigned to settlers.

The third rung, convicts who were assigned to settlers.

The final rung, convicts who were granted conditional freedom via the ticket of leave (refer to Chapter 4).

The final rung, convicts who were granted conditional freedom via the ticket of leave (refer to Chapter 4).

As you behaved in the colony as a convict so you made progress or otherwise. Gone were the good old days of possibly scoring an easy second chance, and gone too was the chance and randomness of the previous regime, where connections could get you out of serving time.

Fighting bushrangers and Tasmanian Aborigines

Aside from evolving better ways to classify and punish convicts, Arthur’s two great challenges in 1820s Van Diemen’s Land were bushrangers and Aborigines. He did well on eliminating the bushrangers, not so well in ending the ‘Black War’ then raging between whites and blacks.

Breeding bushrangers

Van Diemen’s Land has the honour of being the first breeding ground for the stock figures that would later be embraced as folk heroes — bushrangers. Bushranging in Van Diemen’s Land began in the hungry years following first settlement on the River Derwent in 1803, when rations ran so low that convicts were given guns and dogs and told to go out and shoot kangaroos to bring back for food.

Many convicts didn’t come back at all, preferring life in the ranges, living on roo meat, clothing themselves in roo skins, and trading both items for anything else they wanted. They weren’t folk heroes at this point, though, and weren’t above theft and assault on easy prey — small farmers and solitary travellers on the back roads.

Arthur managed to bring Van Diemen’s Land’s incessant bushranger problem under control by turning the island colony into one of the most heavily policed countries in the world. He created a field police force, three-quarters of which was made up of convicts. They were under the control of paid police magistrates, who were answerable to Arthur personally. Arthur’s solution was incredibly heavy-handed — and it worked a treat. Bushranging was quickly eliminated as a social problem.

Fighting the Black War

While the bushranger problem was largely over within the first year of Arthur’s rule, the ongoing armed struggle between Indigenous Tasmanians and white settlers — which included murder and rape on the side of settlers, and retaliatory spearings on the side of Aboriginals — was far more protracted.

Arthur was a man of strongly pronounced evangelical religious views, and at this time it was the Evangelicals who were the most vocal opponents of the British slave trade. Previous to coming to Van Diemen’s Land, Arthur had been administrator of Honduras, and made enemies of the slave owners who dominated local society by exerting himself in the interest of the welfare of slaves and indigenous tribes.

Arthur arrived in Van Diemen’s Land with the strong support of powerful Evangelicals both inside and outside the Colonial Office, all of whom agreed that conflict with native peoples constituted a blot on the reputation of British settlements. He set about trying to reconcile the interests of black and white, but found hostility so entrenched on each side as to be immoveable.

Relations between black and white got so bad that Arthur figured the Indigenous Tasmanians had to be brought in for their own good — and everyone else’s. Removing the Aborigines seemed to him the only way to stop the ongoing bloodshed of the ‘Black War’. There was nothing for it, he thought, but to send roving parties out to capture Tasmanian Aborigines.

This proved far easier said than done. The roving parties met with little success. One of the party leaders, John Batman (who had captured Matthew Brady three years before this — refer to the ‘Tasmanian devils’ sidebar earlier in this chapter for more about Brady) was admonished by Arthur when he attempted capture of Aborigines by sneaking up and firing on them, then shooting two of the captured men because they were too wounded to keep up.

Eventually Arthur turned to George ‘Black’ Robinson, who had the novel idea of trying to make friends with the natives without trying to grab them or shooting at them (see the sidebar ‘Trekking around Van Diemen’s Land’).

Meanwhile Arthur organised the settlers into what would become known as the ‘Black Line’. Conducted in October 1830, it involved practically the entire white male population of Van Diemen’s Land as they marched steadily across the south-east of the island in a long chain with the aim of capturing or at least herding the Aborigines in the region onto a peninsula. Arthur himself rode round exercising his usual hands-on supervision.

In the short term, it proved an unmitigated disaster; only two Tasmanians were captured — an old man and a very young boy. Everyone else had slipped through the chain without anyone noticing. Ultimately though, it was effective as a potent example of just how much in the way of resources and manpower the white settlers could draw on.

A full sense of just how unequal the conflict was dawned on the remaining Aborigines and, after Robinson promised them he would support their rights to the land, they agreed to come in. Perhaps there was misunderstanding, perhaps they’d simply been duped and conned, but once the Aborigines surrendered, they were transferred to Flinders Island in Bass Strait. Here, away from their home country, most quickly sickened and died.

Hitting the Big Time with Wool and Grabbing Land

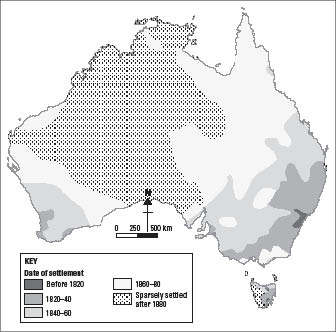

The settlements that would become the states of Queensland, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia all got their start in the 1820s and 1830s. (See Figure 6-1 for how settlement really exploded in the 1820s, and then continued through the 19th century.)

Some settlements began haltingly, as small outposts that were meant to precede greater settlement (such as Queensland and Western Australia). Others came into being as the result of the overwhelming expansion of settlers and livestock against the express rules and laws that were meant to limit this settlement (most particularly in Victoria). And one new settlement came about because people in London were alarmed at the unplanned, ad hoc nature of colonial life, put their heads together and came up with some decent ‘planned settlement’ (see the sidebar ‘No convicts, please, we’re South Australia’ later in this chapter).

Figure 6-1: European settlement of Australia really expanded from the 1820s.

The 1830s, economically speaking and land-invasion speaking, were huge. Building on the steady progress and expansion of the 1820s, momentum took off. The reason behind both the economic explosion and the massive land grab was the same: Wool.

As pastoralism emerged as the dominant factor in colonial life and land was taken up — taken off Indigenous Australians, that is, with a mixture of guns, cajolery, grog and sheer numbers — for the burgeoning wool industry, governors and the British struggled to contain settlement within the previously demarcated limits of administration and law. Settlers kept moving past the limit, squatting on land and occupying it without permission from the government or the traditional Indigenous owners.

To begin with, these settlers were those who were finding it harder to get land — native-born Australians (the children of convict parents), ex-convicts and assorted disreputable types — but soon enough every class was in on the act, taking herds and flocks out in search of good pasturage, and carting back wool and hides in such quantities that they constituted the bulk of the colony’s wealth.

Opening up Australia’s fertile land

In 1835, three men converged on the region of Australia that is now the state of Victoria and contributed to the establishment of the main settlement in the area that would eventually be named Melbourne. One was Thomas Mitchell, a government Surveyor General, another was John Batman, a bushman and grazier, while the third was John Fawkner, a pub-owner, newspaper editor and townsman.

Two of the men — Batman and Fawkner — came separately from Van Diemen’s Land. Both were sons of convicts, but in just about everything else they were very different. Between them (although personal enemies), the seed of what would become a future capital city and colony was planted.

All other settlements that became future capitals — Sydney, Hobart, Adelaide, Perth, Darwin, Brisbane and Canberra — were begun as a result of official government acts. Melbourne, however, began as an ‘illegitimate’ and illegal establishment of private settlers, capitalists, squatters and traders.

John Batman was born in Parramatta in NSW, and as a young man moved to Van Diemen’s Land and became a pastoralist, running livestock, capturing a bushranger, and leading a roving party against Aborigines in rugged terrain. In June 1835 he arrived in Port Phillip Bay (in modern-day Victoria) looking for more grazing country for a syndicate of pastoralists. He struck an agreement with the Wurundjeri tribe, passed near the future site of Melbourne, declared ‘This will be the place for a village’, and soon after started bringing over stock from Tasmania.

Fawkner arrived in Van Diemen’s Land with his convict father under David Collins’ first settlement of the island in 1804 (refer to Chapter 4). He grew up to be a jack-of-all-trades, and soon after Batman’s return from Port Phillip sent over his own party to begin a settlement.

Meanwhile, Major Mitchell, Surveyor General of NSW, established a route down into the new Port Phillip region from NSW, along which countless new settlers would travel. When not surveying he did a lot of exploring, and was one of the first to use Aboriginal place names for various places that he was putting on maps. (His rationale being that when the next whites to pass through the area wanted to go to a place, they could ask the local indigenous people and they could direct them there — requests to see places like ‘King George’s Hill’ tended to provoke blank looks.)

Travelling across modern-day Victoria, Mitchell was so impressed with the quality and fertility of the soil he called it ‘Australia Felix’ — Latin for ‘Australia the Happy’. The soil was so soft that the cart wheels made ruts in the ground that in following years new settlers would also follow: ‘Mitchell’s Line’.

Adding sheep, making money

Australia, with its vast hinterland ready for occupation by men, women and sheep, was in the right place at the right time. The British woollen industry was going into overdrive — thanks to the world’s first industrial revolution, demand from factories for raw commodities like wool was going through the roof. If you’re looking for a moment when Australia’s famous (or infamous) moniker as the ‘lucky country’ becomes relevant, then it lies here.

The raw numbers speak for themselves. In 1830, exports of various fishery products (such as whale and seal) were nearly double that of wool. By 1840, wool exports were nearly triple that of the maritime industries. Land on the other side of the Blue Mountains in the 1820s and further south and north in the 1830s was very quickly turned to the production of high-quality wool, and by 1840 Australia was the dominant player on the global wool market, knocking off Germany (who had knocked off Spain, who earlier had taken care of England) as the leading wool producer in the world.

The development of merino wool in Australia combined the qualities of robust English wools with finer Saxony wool, making it perfect to meet the new fashion for soft and fine cloths after the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The British government reduced duties on colonial wool in the 1820s after it began winning medals for quality, and an 1828 Select Committee declared Australian wool better even than German wool. And it actually cost less for wool to get to Britain from Australia than it did from southern Germany (where the bulk of Saxony wools came from). Australia’s share of the wool trade went from 8.1 per cent in 1830 to 47 per cent in 1850, while Germany’s slumped from 75.8 per cent to 10.6 per cent.

Thanks to NSW and Van Diemen’s Land being such an eager market for imported goods and commodities, plenty of ships were already making the run to Australia. Now they had a staple product to put in their previously empty holds for the homeward journey.

Fighting the land grab

During the 1820s and 1830s in Australia, the economy was going gang-busters. For the authorities, this created one big problem: People, known as squatters, were grabbing land in all directions. The British government was strongly against this dispersed settlement — it was hard to police and made it difficult to keep people under proper authority — and felt it had to be stopped.

At the start of the 19th century, Britain was a small island where in rural areas an intricate social hierarchy still existed — from the squire down to the farmhand, everyone knew where they fitted in the social mosaic. Land was finite, owned predominantly by the wealthy, and the Church was on hand in every country parish to provide sermons about the need for deference and social order. The very idea, then, of practically limitless amounts of land spreading off in all directions, being populated without any order or control by people of all classes, with large herds of their own livestock, did something profoundly disturbing to the English imagination. Just as many in England in the 1800s and 1810s had been horrified at the news of ex-convicts becoming highly successful (refer to Chapter 4 for more on this), so now many were distraught at the thought of this uncontrolled settlement.

The British tried to put the convict upstarts back in their place, and to restrict the allocation of land. Ultimately, however, their efforts were unsuccessful.

Putting convicts in their place

The British elite were greatly concerned about the relatively open nature of society in Australia. If you had initiative, talent or money, you could start getting ahead, regardless of what your class background or upbringing might be. This had to be rectified!

In 1826 Governor Darling began placing tight restrictions on settlement spreading further out from Sydney. In 1829 he declared the 19 counties that surrounded Sydney were the only places where settlement would be permitted. Everything else was trespassing. But settlement outside these boundaries continued.

In one of the most beautiful historical ironies of Australian history, the answer to this great perceived problem was devised by a man who was himself a prisoner but who had never been to the colonies. Edward Gibbon Wakefield was serving time in Newgate Prison in 1829 (for abducting a schoolgirl heiress) when he began writing a series of essays which would eventually be published as A Letter From Sydney.

Wakefield’s idea of how to solve the problem of too much dispersal was very simple. Closer settlement could be enforced by limiting the amount of land freely available and by making the land that was made available more expensive. This would create a couple of benefits:

Members of the lower orders would no longer be able to afford to become landholders straightaway. The high prices would attract investors from Britain who had plenty of capital while people from the lower orders would be forced to work for their betters for a long time as they attempted to save enough money to buy land for themselves. All the while everyone would be living near each other, and would therefore remain under the benevolent thumb of social order and authority.

Members of the lower orders would no longer be able to afford to become landholders straightaway. The high prices would attract investors from Britain who had plenty of capital while people from the lower orders would be forced to work for their betters for a long time as they attempted to save enough money to buy land for themselves. All the while everyone would be living near each other, and would therefore remain under the benevolent thumb of social order and authority.

Money would quickly fill the government coffers (from the land, see), which could be used to bring out male and female free labourers.

Money would quickly fill the government coffers (from the land, see), which could be used to bring out male and female free labourers.

In government circles it was quickly agreed that settlement would have to be more restricted and not allowed to spread beyond certain demarcated boundaries.

In 1831 Viscount Goderich at the Colonial Office (and soon to become the Earl of Ripon) followed Wakefield’s recommendations and introduced new land regulations. The minimum price of land was raised to stop just anyone being able to buy it (to not less than five shillings an acre). Part of the proceeds from the auction would then be set aside to subsidise immigration, and so begin weaning the colony of NSW off convict labour. (For more on Wakefield’s influence, see the sidebar ‘No convicts, please, we’re South Australia’.)

Quietly accepting the inevitable

The British, through Wakefield, Goderich and Governor Darling, did their best to control the allocation of land in Australia, but the settlers themselves largely ignored their regulations. They kept on spreading right out and government was largely powerless to stop them. What were they going to do? Build a big fence and arrest anyone who crossed through it? In 1835, Governor Bourke (who replaced Governor Darling) sternly warned off all the new arrivals at Port Phillip (in modern-day Victoria) as ‘trespassers and intruders’ — then quietly advised Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Glenelg, that they may as well give up trying to limit settlement.

Bourke told the Colonial Office, as politely as he possibly could, that ‘the vast tract of fertile land lying between the County of St Vincent’s and Twofold Bay [in NSW]’ was already used as pasture by ‘flocks and herds, attended by shepherds and stockmen’. Restraining dispersion might be a smart idea in other places, Bourke said, but these pastures were sustaining the flocks that provided the wool that made the substantial bulk of the productive wealth of the colony, and would continue to do so into the foreseeable future. ‘The proprietors of thousands of acres already find it necessary, equally with the poorer settlers, to send large flocks beyond the present boundary . . .’ Aside from all of which was another simple fact — ‘the Government is unable to prevent it’.

Rather than simply issuing diktats that everyone promptly ignored, Bourke suggested it might be better to acknowledge the settlers who were already squatting on land outside the restricted areas. He also suggested more dispersed settlement might be encouraged, to provide ‘centres of civilization and Government, and thus gradually to extend the power of order and social union to the most distant parts of the wilderness’.

The following year Lord Glenelg agreed that Bourke could introduce a licence system for those beyond the established boundaries. An annual rent of £10 gave squatters the right to keep doing what they’d been doing for a while now, although it didn’t give them ownership of the land.

In 1846 The Waste Lands Act was passed in the British Parliament. For the first time it gave squatters security of tenure beyond the annual licences. While not giving in to squatter demands to own the land outright, it gave longer leases of up to 14 years, with rights of pre-emption (first right to buy land) and renewal.

The British Government spent a lot of time and energy in the late 1820s and early 1830s telling settlers in Australia to stop spreading out and taking land without permission — but they didn’t mean indigenous permission. The British didn’t think Aborigines owned the land and they also didn’t think settlers squatting on their own initiative could be said to own the land. They said they owned the land — the Crown. Even today, in Australia public land is called Crown Land.

Aborigines had been denied sovereignty because, in the eyes of European and British arrivals, they didn’t work the land intensively. This was the same description applicable to squatters, who didn’t engage in agriculture, build big structures or visibly alter the environment (although the pitter-patter of millions of hooves on soft feathery top soil would have enormous subsequent effect). In later decades, subsequent arrivals would accuse the squatters of taking up the good land without doing anything substantial with it — the squatters hadn’t introduced any cultivation or heavy settlement. (See Chapter 9 for the struggle between squatters and new gold rush arrivals.)