Chapter 16

World War II Battles

In This Chapter

Trying to avoid war in the 1930s

Trying to avoid war in the 1930s

Standing alongside Britain and facing up to embedded problems

Standing alongside Britain and facing up to embedded problems

Heading off to fight on the other side of the world (again)

Heading off to fight on the other side of the world (again)

Linking up with America as war comes to the Pacific

Linking up with America as war comes to the Pacific

Reorganising Australia’s wartime economy

Reorganising Australia’s wartime economy

Australians in the 1920s and 1930s, like much of the rest of the world, wanted to do anything rather than think about the prospect of war. Hard to blame them — the ‘Great War’ of 1914 to 1918 was enough to cure just about anyone of an appetite for war. Australia put its hopes in an ongoing security alliance with Britain (and the British construction of a strategic port in Singapore), and in appeasement, as Japan, Italy and Germany all showed increasing signs of military aggression in the 1930s.

When World War II began in 1939, Australia did as it had in World War I, by declaring itself at war and on the side of Britain, and sending troops off to the Middle East. Things took a different turn, however, in 1941 when Japan attacked US, Australian and British territories in the Asia-Pacific region. For the first time in Australia’s modern history, it looked as if invasion was not just possible but inevitable as Japan swept dramatically southward, conquering as it went. In the light of this threat, pragmatism forced a new alliance to be forged — with America — and the Australian economy was for the first time shifted to a complete war footing.

In this chapter, I look at how World War II dramatically focused everyone’s thinking about who and what could be relied on to defend the country in a time of crisis.

Building Up to War

Throughout the 1930s, while the international scene looked increasingly grim, plenty of politicians and ordinary people were willing to do just about anything to avoid getting embroiled in another disastrous world war — the memory of the first one was still burned vividly on everyone’s memory.

Australia’s military forces, still being run by men who had commanded the forces in World War I (1914 to 1918), stagnated and declined. Simultaneously, defence spending was slashed because of the Great Depression.

The chief defence policy centred on the British garrison and naval base at Singapore, which had been promised and built (in fairly stop-start fashion) since the early 1920s. Singapore was a naval base without a fleet: Britain had promised to send ships in the event of war in the Pacific. Worried Australian politicians and representatives kept prodding the British for estimates of exactly how many ships would be sent, but no specific answers were forthcoming.

By 1938, Australia had belatedly begun building up its war resources — although politicians continued to argue about the best way to do it. Events of 1941 showed the politicians were right to be worried about Singapore — but also showed that perhaps they should have worked harder in the 1930s to ensure that Australia was more war-ready in a highly unstable international environment.

Defences through the Great Depression

Even though Labor had been one of the main players in setting up a citizen’s militia before World War I, the experience of the conscription controversies in 1916 and 1917 had permanently soured them towards it. (Refer to Chapter 13 for the incredibly divisive impact conscription had on the Labor Party and Australian society in general.) When Labor took power under Jim Scullin in 1929, one of the first things it did was stop compulsory military training for the civilian militia.

Then the economic trauma of the Great Depression hit, and government spending on all non-essentials was slashed. Defence fell into this category, and as a consequence the amount of funding directed to armaments, training and the military dropped drastically in the early 1930s.

At the same time as defence expenditure was being slashed, attempts were made to ensure that the potential (at this stage, anyway) aggressors — Germany, Italy and Japan — were placated. ‘Appeasement’ (which nowadays is often met with derision but in the 1930s was simply the name of a strategy) became the popular slogan.

After another Labor Party split (refer to Chapter 15), Joe Lyons’s new United Australia Party took power from Scullin’s Labor Party in 1931. Lyons was an ‘arch-appeaser’ who was horrified by war. Active in the Labor Party in World War I, he was a strong campaigner against conscription and now wanted to make sure that war was avoided at all cost.

Lyons had long phone conversations with British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (who was also pro-appeasement), and met the Italian dictator Mussolini in an attempt to secure an Anglo-Italian agreement. Even after Chamberlain abandoned attempts to placate Hitler early in 1939, Lyons didn’t give up hope that some sort of settlement could be reached. Like most appeasers, Lyons thought just about anything was worth agreeing to if it meant avoiding war.

Lyons, along with his deputy Bob Menzies, was also active in trying to stop war in east Asia, where Japan had invaded and occupied large parts of China in the 1930s. The Australian Government pushed for a settlement with the Japanese but the British — who had profitable business interests in China — weren’t so keen.

Lyons was prime minister from 1931 till his death in April 1939, and focused on appeasement of the potential aggressors for most of this time. When appeasement didn’t work and war finally broke out, however, Australia, like many Allied nations, wasn’t as prepared for conflict as they could (or should) have been.

Singapore Strategy

The fear of invasion from nearby Asia had been a dominating factor in the original movement to Federation. This obsession meant that in the years following Federation, Australians continued to be preoccupied with the question of what sort of defence could be mounted against potential threats from the immediate north. A nation small in population on a large land mass was felt to be particularly vulnerable and ill-equipped to defend itself.

Britain, however, was still one of the biggest and most powerful nations in the world in the 1920s, and Australia’s security and prosperity was in its interests. As well as involving itself in settlement schemes and development projects (which I discuss in Chapter 14), Britain might also want to make sure that Australia’s defence was taken care of. Singapore was the result of this thinking.

What became known as the Singapore Strategy was a strategy built around the navy and oceanic defence. The British Royal Navy had maintained global dominance at sea for more than a century, and the port of Singapore straddled sea lanes between the Pacific and the British colony of India. Singapore was also close to Australia, which, as an island continent, was thought to be a good candidate for a navy-based defence.

In the 1920s, under an agreement reached with Australia, the British set about turning Singapore into a serious naval base to defend and control the surrounding waters. The base, which was completed in the late 1930s, could comfortably hold and outfit a navy in the case of war — but no navy was provided. Britain gave assurances that in the time of real emergency, ships would be sent, but Australian politicians weren’t assured.

As early as 1933, ex-Australian prime minister Stanley Bruce warned Lyons from London that if war began in the Asian-Pacific region while Britain was already caught up in a European war, the chances of effective British navy reinforcements being sent to Singapore were minimal.

New Labor Party leader John Curtin (who replaced Scullin in 1935) said that Singapore was close to useless in the defence of Australia, but didn’t have much more to offer the national conversation, not offering any realistic alternatives until the late 1930s.

Bruce and Curtin both turned out to be right on Singapore. When war came to the Pacific in 1941, Britain was already up to its neck trying to fight off Nazi Germany and had little to spare for Singapore, which fell in February 1942 (see the section ‘Britain can’t do everything: The fall of Singapore’ later in this chapter). But Curtin, who was by then Australia’s prime minister, had changed his tune. Rather than stick to Curtin’s original line about Singapore being useless as a defence outpost, Curtin’s foreign minister, Evatt, told Churchill (Britain’s prime minister at the time) that any abandonment of it would be seen by Australia as an ‘inexcusable betrayal’. So Churchill reinforced Singapore, and when it fell many thousands of British, Indian and Australian soldiers became prisoners of war.

Belatedly prodded into action

Towards the end of the 1930s, the liberal/conservative parties under Joe Lyons concentrated their efforts at getting guarantees that the British naval base at Singapore would be adequately garrisoned. When no guarantees were forthcoming and as war became more inevitable, new policy measures were adopted to try to rectify Australia’s inadequate defence. For his part, Lyons tried to create a ‘Pacific Pact’ with President Roosevelt in America, but was rebuffed.

The Labor Party, meanwhile, was criticised for being ‘isolationist’ — opponents claimed Labor politicians had their heads in the sand, hoping that keeping out of all overseas conflict would mean no Australians would get caught up in war. Their new leader, John Curtin, had his work cut out coaxing his party to come up with a more viable defence policy.

Curtin was in touch with people in the army who hated the Singapore Strategy (see preceding section) for two reasons:

They were annoyed that the strategy meant most defence funding was going to the navy to support the sea defence idea that was at the heart of the strategy.

They were annoyed that the strategy meant most defence funding was going to the navy to support the sea defence idea that was at the heart of the strategy.

They didn’t think the strategy would work. Britain, they thought, wouldn’t send enough ships in enough time to make any difference.

They didn’t think the strategy would work. Britain, they thought, wouldn’t send enough ships in enough time to make any difference.

Curtin gleaned ideas from his friends in the army and began converting Labor’s defence policy into a more active, self-reliant one. Curtin proposed using planes to solve the defence dilemma, arguing that an air force could be built up in Australia and used purely for local defence purposes, thereby precluding the need to rely on Britain’s Singapore Strategy or other overseas ventures.

In 1937, an election took place that was dominated by the question of defence. Lyons ran a campaign saying the most important thing was to maintain a strong defence relationship with Britain. Labor campaigned on more planes and fewer ships, self-reliance and some links with the US, but lost because they were seen as still too isolationist.

Ironically, after the election win, Lyons became concerned enough about the situation to try to establish American links. And he introduced a significant expansion of the defence budget. In December 1938, a new three-year defence program began to bring Australia to war readiness. As part of the program, £63,000,000 was allocated for training and equipping new troops, building two destroyers, fortifying Port Moresby in Papua (under Australian protectorate control since the defeat of Germany in World War I) and building an air force station in Townsville.

Before the 1937 election, Lyons had signed a statutory declaration promising never to bring in conscription, but in 1938 he recruited Billy Hughes, ex-World War I prime minister and still serving in Lyons’s government, to run a huge publicity campaign to encourage volunteers for militia training.

In July 1939, the government, now led by Bob Menzies (who replaced Lyons as prime minister when Lyons died in early 1939), began a national register of all men aged between 18 and 65. The Labor Party and unions opposed it, saying it wouldn’t be anything other than a kind of conscription database, but the measure went ahead.

Dealing with Early War Problems

In September 1939, war finally began when Germany invaded Poland, which Britain had pledged to protect. Britain declared war and so, as a consequence, Prime Minister Bob Menzies told radio listeners, Australia was now also at war. Although most of the pre-war anxiety had related to threats of war from Japan in the Asian Pacific, Australia found itself again sending troops to the Middle East to fight in a European war.

In the early years of the war, however, Australian troops had their work cut out for them in more ways than one, because, along with the horrors of war, they also had to deal with numerous tactical, organisational and logistical problems.

Problems with tactics and technology

While Britain and other countries were completely overhauling their outmoded World War I tactical theory in the late 1930s, Australia was stuck using old methods and theories. Battle preparation wasn’t brilliant, and tactics tended to the foolhardy. Experience would gradually alter this, as would the removal of the ‘dead wood’ of old commanding officers who were no longer effective in modern battle (see following section).

When it came to technology the Australian forces weren’t well provided for in this area, either. A good example? The Australian 6th Division began the war still using horse transport rather than trucks and vans! Even the biggest traditionalist could recognise that it was time to move on. And communications technology, increasingly important in modern warfare, was woeful. The 6th Division wasn’t issued with wireless sets until after the campaign in Greece in April and May 1941. And the 9th Division — who fought at Tobruk in northern Africa — also had hardly any wireless equipment.

Problems with officer training and promotions

Before the start of the war, officers in the Australian forces were given promotions according to seniority and according to whether they’d served in World War I. This might have worked all right in peace time, when the vast bulk of the armed service was part-time militia, but it couldn’t be sustained in wartime combat.

By the time of the Greece campaign (see the section ‘War in the Mediterranean’ later in this chapter), most of the battalions had new commanding officers, all promoted on merit rather than seniority. On top of that, most of the new officers coming through received the benefit of British training. While Australian officer training in tactics and technology had stagnated in the 1920s and 1930s, the British Army had brought in new officer training material. Fighting with the British in north Africa and the Mediterranean meant the Australian officers benefitted from this — they were sent to British officer training classes.

By 1941, Australian officers were younger, more up to date with training and tactics, and displaying an ability to adapt to new terrain, situations and circumstances.

Problems with weapons

If you’re in a war and you have a problem with weapons, then you really have a problem; this was Australia’s at the start of 1941. There weren’t enough heavy-calibre weapons to support infantry soldiers — which meant Australian soldiers eagerly captured automatic weapons from enemy battalions whenever they could. Neither did Australian troops have any decent anti-tank guns, nor any ‘bunker-busters’. Resolving this dilemma took a while and hampered operations in both north Africa and in Greece and Crete.

Overseas Again

In September 1939, Menzies declared war along with Britain, but he wasn’t keen on the idea of sending Australian forces overseas to fight in places like the Middle East and Europe when Japan remained such a threat locally. But his minister in London — Richard Casey — made some rash promises to match the offer of a division made by New Zealand, which Menzies reluctantly agreed to. In 1940, Menzies and Australia said goodbye to Australian divisions of the second AIF (Australian Imperial Force) to be sent overseas with volunteer soldiers (the first AIF having been the Anzac diggers who went to Gallipoli and the Western Front of France in World War I).

War in northern Africa

The second AIF was being trained in Egypt with the expectation that, like in World War I, they would be sent to a western front in France. From the middle of 1940, however, battles began in north Africa. From early January 1941 at the Battle of Bardia, AIF divisions were involved in the victorious campaign against the Italian Army, then in the more ignominious (yet still fighting) retreat against the Germans, and held out at the siege of Tobruk until December 1941. From July to November 1942, Australian forces were involved in the battle of El Alamein.

In the process, the second AIF made the transition from stodgy pre-war military hierarchy to professional fighting outfit. A lot of the problems in the initial organisation became quickly apparent once in combat (especially against the formidable German Army). The divisions in the Middle East were lucky, however — unlike the 8th Division in Singapore in 1942 (which you can find out more about in the section ‘Britain can’t do everything: The fall of Singapore’ later on), they had the luck of some easy early battles, and were able to make their mistakes and learn from them. By 1942 and the battle of El Alamein, the AIF was a far more adaptive and battle-hardened force.

Capturing Bardia and Tobruk

Bardia was the site of the first Australian battle in the war, and in early January 1941, Australian forces took the town, forcing 40,000 Italians to surrender.

A couple of weeks later, Australian forces won Tobruk from the Italians, taking 100,000 prisoners. No doubt the Australian troops were starting to think, Mate, this is too easy.

With the arrival of Field Marshal Rommel and his formidable German Afrika Korps, things got difficult. Rommel was soon pushing Allied forces back across north Africa, and placing the city of Tobruk under siege. The Australian 6th Division was withdrawn to fight another losing battle (see the section ‘War in the Mediterranean’ later in this chapter) while the 9th Division stayed to fight in Tobruk.

Enduring the siege of Tobruk

Tobruk remained as the last Allied outpost left in north Africa after all the other territory initially won from the Italians had been seized back by Rommel. For eight months troops held out with supplies being run in by sea and on 7 December 1941 Tobruk was finally relieved. During the siege, 800 Australians had been killed during the incessant perimeter battles with Rommel’s Afrika Korps forces.

Winning at El Alamein

The battle for El Alamein in 1942 was one of the epic battles of World War II, where victory swung momentum decisively to the Allies. The 9th Division took part in the main phases of this conflict as part of a British Army that was commanded by General Montgomery.

By this time most of the early problems that the AIF had encountered (refer to the section ‘Dealing with Early War Problems’ earlier in this chapter) had been dealt with. Most of the 9th Division’s battalion commanders were officers who had proved themselves in the 1941 operations. Just as importantly, they finally had enough wireless communications, better heavy weaponry (with plenty captured from the enemy) and even an anti-tank platoon. Amateur hour was over. (For more on Australia’s war effort in northern Africa, see Australia’s Military History For Dummies, Wiley Publishing Australia.)

War in the Mediterranean

At the beginning of 1941, Greece was Britain’s only ally still fighting in Europe. Although the Greek Army had managed to repel the Italian Army, it would have no chance against the Germans.

The campaign to save Greece from German invasion couldn’t even be placed in the ‘really good idea at the time’ category. The campaign looked like a bad idea — one of those doomed hopeless fights that you couldn’t hope to win. Given the various strategic, firepower and manpower advantages the Germans had as their blitzkrieg swung into Greece, the chances of stopping them was effectively zero. But British Prime Minister Winston Churchill convinced his war cabinet (which visiting Australian Prime Minister Bob Menzies was also sitting in) that it was a worthwhile thing to do. Britain had promised Greece that it would do so, and Churchill thought it might impress the Americans, who at this stage were still on the sidelines of the war but watching with interest. Even if it was a doomed campaign, Churchill figured, defending the birthplace of democracy (ancient Athens in Greece) was bound to play well with the Americans — who loved that kind of thing.

Defending Greece may have made some sense within the scope of grand strategy, but down in battlefield it meant doomed endeavours for the largely Australian and New Zealand troops who were being sent in to do the defending. Allied forces lost Greece to Germany and in the process 320 Australians died and 2,000 became prisoners of war (POWs). Australia was learning the hard way about the pitfalls of being a junior partner to large powerful nations caught up in a life and death global struggle.

After getting kicked out of Greece, Allied forces also lost Crete to the downward sweep of German forces. By 1 June 1941, some 15,000 British and Anzac troops had been withdrawn from Crete. The island had been overrun by an army of 30,000 German paratroopers and, even though about 7,000 had been shot as they parachuted down or just after landing, the German assault was too much to withstand.

This Time It’s Personal: War in the Pacific

In many ways the first two years of World War II — September 1939 to December 1941 — went according to expectation for Australia. An Australian volunteer force was raised and sent overseas to fight on the side of the British Allies in far-off places — Africa, Europe, the Middle East — just as had happened in World War I. But on 7 December 1941, things changed dramatically. Japan attacked US, Dutch and British territories throughout South-East Asia, and began a territorial conquest that took more land and sea area at greater speed than any other military campaign in history — better than the Huns, the Romans, the Brits themselves, Napoleon, you name it.

For the first time, Australia itself was threatened with invasion, lost its overseas territories and suffered attack on its towns and cities. With northern Australian towns being bombed, Prime Minister Curtin insisted that Australian troops be sent home and, famously, turned to America for help. America, luckily, decided Australia was an ideal place from which to launch a counterattack.

American and Australian forces managed to turn the tide against Japan, with the Australian military, now a far cry from the amateurish outfit of the late 1930s, proving to be one of the best jungle-fighting forces in the world.

But just as they reached peak efficiency, Australian forces were relegated to a strategic backwater. In the second half of 1944 and in 1945, the man in charge of the American effort in the Pacific, General MacArthur, made sure that only American troops would have the prestige of the final conflicts with Japan. Australian forces were restricted to mopping up operations, many of them of no strategic use whatsoever, but the result of political imperatives — General Blamey from the Australian Army and Prime Minister Curtin needed to keep Australian forces fighting in order to improve Australia’s bargaining power after the end of conflict.

Britain can’t do everything: The fall of Singapore

Ever since the beginnings of white settlement in 1788, Australian security had been predicated on the protection given the country by the British Empire. For practically the entire 19th century, Britain had been the undisputed global superpower. This situation had changed during and immediately after World War I, but in Australia it took a while to sink in.

The strategic linchpin of Britain’s defence of Asia, India and Australia was the sea port of Singapore on the Malay peninsula. Since the port was established in the early 1920s, Australia had been assured that no enemy could harm it while Singapore was held by the British. Consequently, Singapore’s fall sent shockwaves through Australian society.

On 8 December 1941, a massive Japanese air force began its assault on British Malaya. A large Japanese landing force also began to make its way with lightning speed down the Malay Peninsula towards Singapore, which lay at the very tip. The Australian 8th Division was sent in to reinforce the defence.

Previous to the Japanese invasion of Singapore, the assumption had been that the only threats to Singapore would come from the sea, because the land to its north was seemingly impenetrable jungle and heavy scrub. The Japanese soon proved the terrain to be quite penetrable indeed, especially when utilising their driving charge tactic — taking calculated risks to keep forward-moving momentum constant and keep the enemy (in this case, Indian, British and Australian troops) on the back foot.

Japanese forces used a high-tempo, fluid form of fighting and the Australian 8th Division was completely unable to combat it. The Australians also had the following factors against them:

They were given practically zero sea or air support.

They were given practically zero sea or air support.

The Singapore guns were set in concrete and pointed out to sea (invasion from land seeming that inconceivable to the boffins who’d planned the defence originally).

The Singapore guns were set in concrete and pointed out to sea (invasion from land seeming that inconceivable to the boffins who’d planned the defence originally).

They hadn’t had the chance to develop into a formidable fighting force as had the other AIF divisions serving in north Africa (refer to the section ‘War in northern Africa’ earlier in this chapter).

They hadn’t had the chance to develop into a formidable fighting force as had the other AIF divisions serving in north Africa (refer to the section ‘War in northern Africa’ earlier in this chapter).

The last factor in the preceding list was probably the biggest issue. At the start of the war, Australian forces had faced chronic problems (refer to the section ‘Dealing with Early War Problems’ earlier in this chapter). Whereas other divisions had been able to get over these problems during months of more low-level skirmishing and battles against often substandard enemies, the 8th Division got hit by a ruthless and tactically brilliant fighting force almost as soon as it stepped off the boat.

Singapore fell on 15 February 1942 and 13,000 Australian soldiers from the 8th Division became Japanese prisoners of war.

Attacks on Australia

Australian towns on the northern coast were especially vulnerable to Japanese attack because the Japanese were intent on eliminating any potential airfields that might threaten their occupation of Java, Borneo and Timor. In early 1942, Japanese forces launched attacks on the Australian mainland.

In Darwin, 243 people were killed on 19 February 1942. Two weeks later, the Battle of the Java Sea took place and HMAS Perth was sunk, with half the crew of 680 being killed. Dutch, British, Australian and American warships all attempted to halt the Japanese advance but were comprehensively beaten. On 3 March 1942, 70 people died in Broome from Japanese bombing, and casualties were also suffered at Wyndham. Invasion and occupation by the Japanese became a real threat.

Over 21 months, Darwin was attacked 64 times by Japanese bombers, the final raid occurring on 13 November 1943. Overall, 97 attacks took place on northern Australia in 1942 and 1943, on Darwin, Broome, Wyndham, Derby, Katherine, Horn Island, Townsville, Mossman, Port Headland, Noonamah, Exmouth Gulf, Onslow, Drysdale River Mission and Coomalie Creek. All of a sudden Australia felt very much alone — and northern Australian especially so.

Um, America — can we be friends?

Luckily for Australia, America was drawn into the war against Japan when Japan launched its initial attacks in 1941, which included bombing Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and attacking American territories in the Philippines. Even more luckily for Australia, America decided that Australia would be an ideal place in which to build up its own forces and from which to launch a counterattack across the Pacific. President Roosevelt ordered American General Douglas MacArthur to take up a command post over the South-West Pacific Area, with headquarters in Australia, and soon after American forces and equipment began to arrive in Australia.

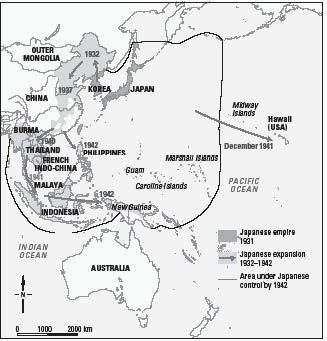

In March 1942, General Douglas MacArthur arrived in Australia, establishing headquarters in Melbourne, before moving it to Brisbane for the launching of offensives. People breathed a big sigh of relief: ‘Thank God for the Yanks’ was the general sentiment. By this stage, the general feeling was that the Japanese forces were at Australia’s door — see Figure 16-1 for just how much area was under Japanese control by 1942. Even though MacArthur and the Americans had had their own bungles and defeats — such as Pearl Harbor and surrender in the Philippines — the overriding sensation when MacArthur arrived was that things would now turn out all right.

Figure 16-1: By 1942, the area under Japanese control included parts of the Pacific and South-East Asia.

By June 1943, close to 178,000 American servicemen were based in Australia. Overall about 1 million Americans passed through Australia during the war, most of them arriving during 1942. This passage made them the greatest temporary influx of foreigners in Australian history, barring the gold rushes of the 1850s, and their impact on Australian life, and women’s lives particularly, were profound and far-reaching (see the sidebar ‘Here come the Americans: “Overpaid, oversexed and over here”’ for more on this).

Turning the tide in the Coral Sea and on the Kokoda Trail

Through 1941 and the start of 1942, the Japanese Army swept through Asia and the Pacific with unbelievable force and speed. But in May 1942, the tide of the war started to turn in the Allies’ favour, with the first real defeat of Japanese naval forces in the war — the Battle of the Coral Sea.

The Japanese were intent on capturing the strategically vital Port Moresby: If Port Moresby was taken, their control of the surrounding sea lanes would have been close to total. In early May, ships from the US and Australian navies moved to stop the Japanese.

The two fleets (Allied and Japanese) never sighted each other because this more modern naval battle involved aircraft carriers launching planes on long-range bombing raids on the enemy’s ships. Both sides suffered loss of lives and ships, and although Japan won the battle on points (numerically more ships were sunk on the Allied side), the forward momentum of the most rapid territorial invasion in history was for the first time blocked.

On 21 July 1942, the fighting moved onto land, as some 13,000 Japanese troops landed on the north coast of New Guinea and begin a rapid advance up the Kokoda Trail towards Port Moresby. The Australian civilian militia (who by law were only allowed to fight on Australia’s mainland or its territories), heavily outnumbered, fought a rearguard battle.

Reinforcements arrived in the form of AIF divisions fresh from the Middle East and, for the first time, civilian militia and volunteer soldiers fought together on the Kokoda Trail. By September 1942, Australian forces had turned the Japanese back. This (and Timor) was the closest to Australia that Japanese forces ever advanced.

Jungle victories

In 1942, the fighting against Japan had been a combination of pure desperation and scrambling defence. In 1943, the initiative began to swing. Victories on the Kokoda Trail (refer to the preceding section) and at Milne Bay on the east coast of Papua helped soldiers realise how to fight best in jungle terrain. Australian troops now saw that, after a long period of seemingly invincible progress, Japan could be beaten in jungle warfare.

In New Guinea in 1943, Australian forces had the task of capturing Japanese bases on the Papuan coast, and so enabling the seizure of crucial nearby waters — the Vitiaz Strait, Dampier Strait and the Bismarck Sea.

The 1942 experience of fighting in jungle in the earlier campaigns in New Guinea had been a shock for troops in the AIF who had mostly trained in Egypt and fought in the deserts of northern Africa. However, by the time of the New Guinea campaigns of 1943 and 1944 — at Salamaua, Wau, Lae and Suttelberg — the Australian military was coming to grips with the tropical terrain, whether in hill country, mountains, river estuaries or grasslands.

After learning the tactics of successful Japanese attacks, Australian troops began adapting and using the same tactics: ‘Bush-bashing’ (beating a path through the thick jungle) round the enemy flanks was used effectively, as was continual infiltration and penetration of enemy lines. Junior commanders began exercising increased responsibility as units operating in the field became more dispersed in their operations. Commanding officers became better at delegating autonomous roles to these junior commanders, and better at taking feedback from immediate subordinates. The mentality underlying Australian operations became more fluid and flexible, as the Australian divisions began to establish tactical dominance over Japanese forces.

At the same time, Australia began to enjoy material dominance as well. By the time of the New Guinea offensives of 1943 and 1944, Australian troops were better supplied than the enemy (using innovations such as dropping supplies in with parachutes), and had superior numbers as well. In early 1943, six infantry divisions — three AIF and three militia — were restructured as ‘jungle’ divisions. The amount of artillery and vehicles was reduced (not many roads in the jungle) and everything not essential for general operations in jungle conditions was eliminated.

Petering into significance

The upside of having America on Australia’s side was clear, but the downsides were notable as well. Any alliance with an emerging superpower was always going to be a highly unequal partnership. General MacArthur proved a great wartime leader to have onside for as long as his ambitions, America’s wishes and Australia’s needs were all in sync — which they were for most of 1942 and 1943. But from 1944, as the advance on Japan picked up pace, MacArthur made sure that only American forces were used for — and would get the credit for — the front-line re-conquests. Unlike its dealings with Britain, where the War Cabinet often accepted Australian input, Australia was largely shut out of the real planning and decision-making that was taking place at the apex of power.

From April 1944, Australian troops no longer had any great importance to MacArthur. Whereas initially he’d had to rely almost entirely on Australian troops, plenty of American divisions were now at his disposal. He began landing American troops well in advance of Australian troops and sending Australian troops on mopping-up operations against Japanese forces that had been effectively knocked out of the active theatre of war.

In 1945, Australians were part of the campaign to take Java and Borneo. They were also involved in clearing the Japanese from Australian-mandated territory — Bougainville, New Britain and the Aitape-Wewak region of New Guinea. By this time, the Australian Military Forces (or AMF — the combined forces of the AIF and the Australian militia) had emerged as one of the most capable and effective jungle fighting armies in the world. The Japanese had been defeated by them in every campaign since 1943, and the British Army were eager to get AMF expertise for jungle warfare at any opportunity.

Bob Menzies (who was leader of the federal opposition at the time, after losing power in 1941) said the 1945 campaigns had ‘no relation to any first-class strategic objective in this war’. He was right. But Australian Prime Minister John Curtin wanted to make sure that Australia had some say in how the postwar Pacific was to be dealt with — and fighting was the chief way of ensuring this, even if the fighting was strategically useless. Curtin claimed, ‘Australians wish to have a say in how the Pacific area is to be managed, and we realise that the extent of our say will be in proportion, not to the amount of wheat, meat or clothes we produce to support the forces of other nations [like, for instance, America], but the amount of fighting we do’.

Curtin’s claims made perfect sense on a geo-political level, but for the troops on the ground it was hard fighting battles that were ultimately pointless. It was also not great for morale for battlefield commanders to receive — as actual battle directions — instructions from army leaders such as ‘Take your time. There’s no hurry’.

Tackling Issues on the Home Front

The biggest changes for most Australians during World War II were on the home front. For the first time, the whole economy was converted to production for war needs. Heavy industry was developed for the production of weapons, and leading businessmen and industrial bigwigs were brought in to oversee centrally planned industry. Rationing and control was built up under new government bureaucracies, women flooded the workplace and a new tax system was brought in.

Industrialisation and business expansion

In the late 1930s, heavy manufacturing started to become more important to the Australian economy. During World War II, this sort of manufacturing became the new kingpin, as Australian factories started producing automobiles, chemicals, electrical products, iron and steel.

War was the pivot in Australia’s economic transition to manufacturing. A combination of new military requirements and needing to fill the gap left by overseas imports (which during the war were no longer reaching the country) meant new industries were developed or boosted. Great improvements were made in output, technical capacity and management of all different levels of production (from the factory floor to investment management divisions).

The new focus on manufacturing would put Australia in good stead for the postwar years, as skills were acquired, big plants established and multinationals moved in with big investments of capital to help expansion. For the first time, manufacturing productivity per worker was greater than that on farms. (See Chapter 18 for more on the long boom conditions that began in the 1950s and manufacturing’s role in the prosperity.)

Rationing and control

As the whole nation applied itself to the fighting of war, a shift from meeting peacetime needs to meeting wartime needs took place in the Australian economy. This shift involved government intervention to cut back production for consumer demands — in a word, rationing. Aside from the governmental mechanisms to make this happen, ordinary people had to be persuaded that rationing was a good thing to happen. The federal government swung its publicity machine into action, creating propaganda to encourage people to embrace these new restrictions with enthusiasm.

In October 1940, petrol rationing was introduced. In June 1941, Menzies got back from a few months in Britain, convinced that things were serious and that Australians weren’t worried enough about the threat posed by global war. He declared Australia to be on a total war footing and announced new measures to:

Control shipping, road and rail

Control shipping, road and rail

Increase the workforce with women and others who weren’t enlisted

Increase the workforce with women and others who weren’t enlisted

Further restrict petrol use for civilian purposes

Further restrict petrol use for civilian purposes

Increase defence measures

Increase defence measures

In 1941, the new Labor government inherited these measures to create a thorough system of rationing to control what was made and built, but the implementation of these measures was quite shambolic. The scheme was overseen by the Tariff Board, with heads of different government departments unaware of what it was designed to achieve let alone how it would be implemented.

Prime Minister Curtin appointed a new Director of Rationing (Herbert ‘Nugget’ Coombs; see Chapter 17 for more on Coombs) who got in touch with economic planners in Britain who had been tackling the same problems, and grabbed as many available thinkers and bureaucrats as he could to get things moving.

The policies produced by Coombs and his team worked. Coupons for food and other commodities were introduced as the production of many items, including beer, was limited. Company profits were restricted to 4 per cent per annum, with prices controlled to ensure this happened. In February 1942, the Prohibition of Non-Essential Production Order was introduced, which listed the articles now forbidden to be produced. In September 1942, the Curtin Government launched the first of a series of ‘austerity’ campaigns, linking the idea of austerity at home with helping the war effort abroad.

Coombs and his team did such a good job of developing wartime policies — and then selling those policies to Australians — that Prime Minister Curtin took the stop-gap team of publicists, academics and bureaucrats and made them the core of what would become the most significant governmental shaper of subsequent decades of Australian life: The Department of Post-War Reconstruction (see Chapter 17).

Women in war times

During the war, as men were leaving for fighting overseas, many women entered newly opened positions, both in the armed forces and at home.

In April 1941, the Minister for the Navy (Billy Hughes, who had been Australian prime minister in World War I) decided to let women be employed as telegraphists in the Royal Australian Navy. Soon after this, a Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service was formed. In August 1941, the Australian Women’s Army Service was created, and by 1945 it numbered some 25,000.

Women also stepped in to fill the gap left by men in industries at home. Women tram conductors began working in August 1941 and other industries followed. In 1942, Labor Prime Minister John Curtin established the Women’s Employment Board to regulate wages and conditions for women doing ‘men’s work’ for the duration of the war.

For the first time in many industries, women during World War II were getting paid at equal rates to men — which meant that women’s pay effectively doubled.

Taxing everyone and building a welfare system

As well as introducing rationing and implementing more control of everyday life (refer to the earlier section ‘Rationing and control’), Curtin also introduced new tax and welfare measures during the war that would have far-reaching effects on the lives of all Australians for years to come.

In April 1943, a new federal income tax system was introduced, with ‘pay as you go’ instalments deducted from each wage payment. This tax was in addition to the extra Wartime Tax that all companies were already paying. The tax system was new in two ways. Firstly, it was a move made by the Commonwealth to take away the state’s power to raise income tax. Secondly, income tax was now applied not just to the middle class, but to workers as well — and this from the party of the workers, Labor!

Because it was wartime, and because the Commonwealth promised big revenue returns to the states, the states were in a position where they couldn’t really persist with their income taxes. Little fuss was made, but the designers of the Constitution and the Federation-era politicians would have been shocked if they were still around to see it (not many were). Raising income tax had always been assumed as a basic plank of the states’ rights, and now it was gone. This was the decisive moment in state–Commonwealth relations for the entire 20th century. After this, there could be no mistaking who wore the big boots in the Federation house.

The main reason for this new taxation approach was economic — income had been shooting up in the boom conditions of full employment during the war, and the government wanted to soak up a lot of this excess spending power. If it didn’t, too much would have been spent on beer and the trots! Inflation was proving a problem, and all resources that could be redirected to serve the war economy should be made to do so. However, the new taxation approach also meant Labor could implement a system based on another of its core goals — building a welfare safety net for all citizens.

Previous to World War II, Labor’s policy on introducing welfare was simple — ‘the rich should pay’. A welfare scheme put forward by ex-Labor prime minister Joe Lyons in 1938 had been knocked back by Labor because it proposed to tax everyone — workers, the middle class and the rich. In 1943, however, the Labor government under Prime Minister John Curtin and Treasurer Ben Chifley did just that.

In February 1943, Chifley announced plans for the new tax and for a new welfare state in order to build ‘a better future for the world . . . [to secure] for all . . . improved labour standards, economic advancement and social security’. Chifley’s announcement was immediately denounced by one of Labor’s own senators, Don Cameron, who called it ‘a confidence trick . . . which won’t mean any increased purchasing power for the working masses’, and the Melbourne Trades Hall Council debated whether to support or attack this new change in Labor policy. Chifley’s response was to deny the accusation that he was selling out the working class by taxing them. ‘If there is to be a universal right to all the benefits, then there should be a universal contribution, and I have no doubt that in time this form and system . . . will be applied in most countries of the world.’

Chifley, and Curtin’s Labor Government, was right. Under pressures of inflation and the demands of a wartime economy that was straining at the leash, the welfare state was born. In the decades following, similar measures were applied throughout the western world.