Chapter 17

Making Australia New Again

In This Chapter

Focusing again on innovative legislation

Focusing again on innovative legislation

Remaking Australia in a postwar world

Remaking Australia in a postwar world

Ending the old ‘Brits-only’ migration policy

Ending the old ‘Brits-only’ migration policy

Finding a new voice on the world stage

Finding a new voice on the world stage

Going too far down the nationalisation path

Going too far down the nationalisation path

After World War II came the reconstructing. For Australia, this was more than simply reverting from a wartime society to the previous world of peace. Under new Labor Prime Minister Ben Chifley, reconstruction aimed for an ambitious remodelling of Australian society — one that would fix the problems that had led to economic depression and social disaster in the years previous to war. The massively increased powers given to the federal government during the war made sweeping change possible.

The first Minister for Immigration, Arthur Calwell, set about fast-tracking Australia’s social, economic and demographic changes with a radical new migration program which — for the first time — encouraged non-British migrants to move to Australia in large numbers. In foreign affairs, a new engagement with world politics developed; Australia’s Minister for External Affairs, ‘Doc’ Evatt, played a pivotal role in the formation of the United Nations, and leaders continued to question who to be ‘besties’ with (with Britain again coming out the winner).

This chapter looks at the rapidly changing world of postwar Australia. Not every change worked out as planned, but the postwar period had a huge impact on the Australia we know today.

Restarting the Social Laboratory Under Chifley

After World War II, the vision of Australia as a social laboratory in which society could be radically changed for the better — a vision that had been put on hold during the previous three decades of war, social division, economic depression and more war — became a real possibility again. The man chiefly responsible for seeing the vision become reality was Ben Chifley.

Ben Chifley was born in the 1880s and could remember the great bank crash and economic depression of the 1890s (refer to Chapter 11). Growing up in NSW he’d worked on the railways and eventually become a member of the ‘labour aristocracy’ — a train driver.

Chifley remembered his time as a train driver fondly, saying, ‘I used to get a lot of pleasure at night with 14 carriages behind me. There was always something fascinating about the eyes of 14 carriages looking at you round the bends. . . . I feel I have kept so close to engine-driving that I could go back to it tomorrow. You know, when you’re driving an engine you’ve got a lot of power. They may question your decision afterwards, but, while you’re in charge of that engine, nobody can!’

In government and as prime minister, Chifley proved himself to be a master when it came to driving the country’s biggest engine. John Curtin made him treasurer and also Minister for Post-War Reconstruction during World War II, and Chifley soon became something more than the right-hand man. While Curtin argued with Churchill and worried himself sick about returning soldiers and the problems of fighting a war, Chifley had the task of keeping the country running. He did it so well that after Curtin died in 1945, Chifley was voted in by the Labor Caucus as prime minister, despite not being formally Curtin’s deputy.

Most of Chifley’s best work was done behind the scenes — before meetings, in meetings, after meetings, smoking his pipe and yarning with other members. He soon showed his capacity for real presence on the prime ministerial stage as well, overseeing a greater amount of serious legislation in the parliamentary term of 1946–49 than had occurred in any parliamentary session since Federation.

The Chifley Government was elected in the 1946 election with a strong majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. Many of Chifley’s plans had been in the works for years before that.

Labor in the 1940s saw themselves as architects of a new society, as trailblazers in the making and unmaking of social conditions. As Chifley put it, ‘I try to think of the Labor movement [as] bringing something better to the people, better standards of living, greater happiness to the mass of the people. We have a great objective — the light on the hill — which we aim to reach by working for the betterment of mankind not only here but anywhere we may give a helping hand’.

Labor’s greatest achievements — and their biggest blunders — during this period stem from this one ambition.

Chifley’s Postwar Reconstruction

Chifley got his start planning the ‘new’ Australia when Curtin set up the Department for Post-War Reconstruction in 1942 and appointed Chifley department minister. Chifley brought in the young maverick bureaucrat Herbert ‘Nugget’ Coombs from the Department of Rationing for the job of drawing up blueprints for Australia’s future.

After Chifley became prime minister in 1945, the plans that had been developed by the Department of Post-War Reconstruction over the previous three years began to be put into action. The expanded powers of the Commonwealth Government didn’t go down well with everyone, however, and Chifley soon found himself facing challenges in the High Court.

Focusing on public works and welfare

The postwar Zeitgeist was to use government planning to make society a fairer and more prosperous place for all. Prime Minister Chifley was determined to make Australia a new place, with more opportunities and better protection for everyone in it, to ensure that the various calamities of the past 50 years — economic depressions, world wars, bank failures — were eliminated entirely. Chifley embarked on a project to remake Australia and, overall, he was remarkably successful.

Some of the postwar plans that were implemented include

A set of public works to be initiated at the first sign of a fall-off in full employment conditions

A set of public works to be initiated at the first sign of a fall-off in full employment conditions

A housing program to deal with the construction backlog from the 1930s Depression and World War II

A housing program to deal with the construction backlog from the 1930s Depression and World War II

A policy designed to protect low-income workers and their families from the expected postwar leap in rents and prices

A policy designed to protect low-income workers and their families from the expected postwar leap in rents and prices

An offer to ex-servicemen to upgrade education qualifications, attend university and improve technical skills

An offer to ex-servicemen to upgrade education qualifications, attend university and improve technical skills

The 40-hour week

The 40-hour week

New dental and medical schemes, new hospitals and increased medical research

New dental and medical schemes, new hospitals and increased medical research

The founding of the Australian National University

The founding of the Australian National University

A reorganisation and expansion of CSIRO

A reorganisation and expansion of CSIRO

The establishment of a national shipping line

The establishment of a national shipping line

The establishment of a compulsory wheat stockpile

The establishment of a compulsory wheat stockpile

The agreement with General Motors to begin manufacturing the first all-Australian built car, the Holden

The agreement with General Motors to begin manufacturing the first all-Australian built car, the Holden

Developing the public service

As Chifley’s Government ramped up its postwar reconstruction, so too was Commonwealth bureaucracy transformed and rapidly expanded, opening up new opportunities in the public service. This meant that plenty of young intellectual talent entered the public service and went straight into elevated positions of authority, representing an influx of new ideas and energy that hasn’t been seen in government departments before or since. More than any other department, these new recruits gravitated to Chifley’s Department of Post-War Reconstruction, forming the ‘Chifley brains trust’ (what Chifley liked to call his ‘long-haired men and short-skirted women’) and shaking up government planning.

By and large, this new group in the public service had been educated in the 1930s. During the chronic unemployment and destitution experienced in the Depression, their thinking had been sharpened into a determination to radically alter society, focusing on social equality and economic fairness. None of these people had been government bureaucrats before the war, and all lacked the traditional conservatism that public servants tended to have.

The most well-known and influential of these young people who were rethinking society was Herbert ‘Nugget’ Coombs (see the sidebar ‘Coombs: Nugget dynamo’ later in this chapter).

Although in staff numbers the Department of Post-War Reconstruction was one of the smallest of all government departments, it had the most wide-ranging sphere of influence. Within it, the ‘brains trust’ dealt in research, planning and publicity — they came up with the new plans and ideas for the postwar period and then used marketing and publicity to sell them to the Australian people.

Increasing legislative interventions

Chifley’s government brought in a great deal of legislation that aimed to increase the power of the federal government to intervene in the daily life of Australian society.

Legislation introduced by the Chifley Government includes the following:

Aluminium Industry Act, establishing a joint Commonwealth–state authority to smelt aluminium

Aluminium Industry Act, establishing a joint Commonwealth–state authority to smelt aluminium

Australian National Airlines Act, setting up an aviation monopoly under one government-controlled airline, Trans Australian Airlines (TAA)

Australian National Airlines Act, setting up an aviation monopoly under one government-controlled airline, Trans Australian Airlines (TAA)

Commonwealth and State Housing Agreement Act, setting up a commission to oversee the construction of public housing for rental not purchase

Commonwealth and State Housing Agreement Act, setting up a commission to oversee the construction of public housing for rental not purchase

Commonwealth Bank Bill, giving the Commonwealth power to centrally direct banking and control monetary policy

Commonwealth Bank Bill, giving the Commonwealth power to centrally direct banking and control monetary policy

Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Act, entrenching arbitration as the essential mode of resolving industrial disputes, against militant (and communist-controlled) unions like the waterfront and coalminers unions

Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Act, entrenching arbitration as the essential mode of resolving industrial disputes, against militant (and communist-controlled) unions like the waterfront and coalminers unions

Education Act, establishing a Commonwealth Office of Education and a Universities Commission

Education Act, establishing a Commonwealth Office of Education and a Universities Commission

Pharmaceutical Benefits Act, giving people access to cheap medicine

Pharmaceutical Benefits Act, giving people access to cheap medicine

Coming up against High Court troubles

After World War II, and at the same time as Chifley was trying to expand Commonwealth powers (see preceding section), High Court judges began to reverse an earlier precedent set down in 1920 in the Engineers Case (which you can read about in Chapter 14).

The earlier 1920 ruling essentially gave the Commonwealth permission to push the scope of its power to the very limits originally set down in the Constitution. From 1946 on, High Court judges began to set aside this ruling, and went back to an earlier interpretation. Known as ‘inter-governmental immunity’, this earlier interpretation largely meant that state governments had their own sphere of powers, and the Commonwealth should do everything to stay out of it.

This meant that Chifley’s Labor government, which after the 1946 election enjoyed unparalleled dominance in both houses of parliament, began to find that its greatest obstacle was not in the House of Representatives or Senate, but among the group of judges whose job it was to interpret the Constitution.

Some of the major pieces of legislation passed by the Chifley Government but knocked back by the High Court include

Pharmaceuticals Benefits Act (although the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme survived)

Pharmaceuticals Benefits Act (although the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme survived)

Australian National Airlines Act (although TAA survived)

Australian National Airlines Act (although TAA survived)

Banking Act (which also helped knock Chifley out of government — see the section ‘Treading on an Ants’ Nest — of Angry Banks’ later in this chapter)

Banking Act (which also helped knock Chifley out of government — see the section ‘Treading on an Ants’ Nest — of Angry Banks’ later in this chapter)

Calwell and the Postwar Migration Revolution

In the 1940s, Australia experienced a conversion on the issue of migration that would change the basic nature of its society. In a ‘Brits-only’ nation with an anti-immigration stance against non-Brits that fitted with the fortress mentality of a small Australia, a new policy took hold, one that embraced large-scale growth and European migration. The new policy was supported by both sides of politics but it became the personal project of Labor’s Arthur Calwell, the first immigration minister. Under his guidance, the migration project was used to not only fast-track Australia’s development but also to break the mould of old ‘establishment’ Australia.

The one big migration scheme the Australian Government had been involved with in the first 40 years since Federation had been an unmitigated disaster (refer to Chapter 14). However, World War II had quickened everyone’s thinking about the need to expand the nation’s population. A paper prepared by the Menzies government in 1941 gave high priority to postwar immigration: ‘We must build up our population to the extent that we shall be able to defend ourselves, and also have a balanced economy’. This policy had been continued by the Curtin Labor government, even when most were expecting and fearing an economic downturn at the end of the war, with heavy unemployment.

After World War II, two completely new factors emerged: The realisation that the required increase to Australia’s population couldn’t be met by Britain and a desire to create a (slightly) more mixed society.

Looking beyond Britain to meet migration needs

Before 1914, Australia had one of the highest rates of natural population increase in the western world — some 17 births per year per 1,000. This collapsed dramatically over the next 20 years to be 7 per 1,000 by the 1930s. Although population growth had picked up again in World War II (reaching 11.5 per 1,000), it was expected to drop away again afterwards.

Meanwhile, thanks to war and the real threat of invasion, politicians of all stripes were announcing that Australia needed to quadruple its population within 15 to 20 years, to get to about 20 million by the early 1960s. This was hyperbole (representing an increase of some 11 million migrants, more than double the existing Australian population), but it set the tone of the debate. Whereas all previous discussion of migration had been hemmed in by fears that too many new arrivals would mean fewer jobs to go round, now the vision of sustained growth and rapid development took hold.

Just one problem existed. The inter-departmental committees who were researching and reporting on this matter soon realised that there was no way in the world that all those migrants could be supplied by Britain, as all government-planned migration had been previously. If large-scale migration was to go ahead, it would require not just British but European immigrants (it didn’t even begin to occur to policy-makers to think about letting in non-Europeans), who were quaintly titled ‘white alien immigrants’. Politicians feared this would be a hard sell to a populace that prided itself on its 98 per cent British stock and its almost entirely British cultural patterns and public institutions.

The solution? Don’t tell the public! A public relations smokescreen was put in place, whereby new immigration minister Calwell could assure the public that while some immigrants would be needed from the European continent, for every one European ten British migrants would arrive, thereby ensuring the previous ethnic ratio would be maintained. This, however, was never remotely possible, and in the years that immediately followed the ratio was often the reverse.

Breaking the mould of mainstream Australia

Calwell, Labor member for the parliamentary seat of Melbourne, had strong incentive to become minister for immigration, and strong incentive for a heavily non-British level of migration. He wanted to do more than fast-track Australia’s development — he wanted to junk the English Protestant culture that had become such a dominant factor in mainstream Australia.

The ‘social laboratory’ experiment that Australia had embarked on after Federation had been built on a successful multiethnic consensus — that of ‘Britishness’. Colonial Australia had been made up of traditional ethnic antagonists — English, Irish, Scots and Welsh — who had been thrown together higgledy-piggledy. Surprisingly, wonderfully, they had managed to get along. This had come apart during World War I, thanks to overseas events (rebellion in Ireland) and local ones (the conscription controversy), when Irish Catholics were accused of being anti-Britain and anti-war. The Labor Party split, lost just about all of its Protestant British parliamentary members, and became dominated by the ethnic and religious minority Irish Catholics (refer to Chapter 13 for more on this). Calwell, although himself — and like most Australians — a composite product of Irish and Welsh, Catholic, Anglican and Protestant, identified strongly with the Irish Catholic strand and became hostile to mainstream and establishment Protestant Australia. He came of age during this massive change in Australian life, and was deeply marked by it.

In 1944, Prime Minister Curtin went to England where he declared Australia as ‘trustees for the British way of life’, and stepped up plans to recruit British orphans and ex-servicemen with assisted passage to Australia after the war. But Calwell (at the time Curtin’s Minister of Information) was developing a very different idea of how to manage immigration. He wrote to then-Treasurer Chifley, telling him he thought Australia needed a Department of Immigration, and he was just the man to run it.

Calwell wanted a ‘polyglot Australia’, more like the American melting pot society than the homogenous Australo-British. He told Chifley of his ‘determination to develop a heterogeneous society: A society where Irishness and Roman Catholicism would be as acceptable as Englishness and Protestantism; where an Italian background would be as acceptable as a Greek, a Dutch or any other’. This, in Australia in 1944, was little short of a revolution in social attitudes.

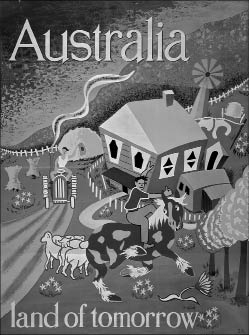

Within a year, Calwell was immigration minister and implementing his changes. He established new Immigration Department offices in New York, Ottawa, New Delhi and San Francisco. He set off on a whirlwind overseas trip, visiting 23 countries (most of them in Europe) in just over 12 weeks, working out deals with governments and migration bureaus and getting the great postwar migration experiment rolling (see Figure 17-1 for an example of an emigration poster from this period).

Figure 17-1: An emigration poster from 1948.

Between 1947 and 1949, the numbers of new immigrants in Australia increased more than fivefold, from 31,765 to 167,727, and between 1947 and 1951, Australia received more than 170,000 postwar refugees from Europe.

Most of these immigrants and refugees were immediately christened ‘Balts’ by Australians — because many of the nations they came from surrounded the Baltic Sea — or just ‘Refos’. Calwell, however, came up with a new name to use instead of the derogatory terms being invented: ‘New Australians’.

The radical new direction in Australia’s immigration and development was never put to Labor Caucus, let alone the Australian people at an election or referendum. Even the ‘Displaced Persons’ program to accept postwar European refugees was agreed to only by Calwell and Chifley, and never taken to cabinet. A very good reason existed for this lack of openness and transparency — if asked their opinion in these cases, the Australian people, the Labor Caucus and cabinet would most likely have all said a resounding No to the idea. Yet despite this, the postwar migration experiment proved to be a big success, as most Australians showed a capacity for tolerance to these new arrivals (helped by a booming economy and full employment).

Within a generation Australia had undergone the greatest ethnic, linguistic, cultural and demographic transformation of any nation in modern history, aside from the post-1948 state of Israel. And the dominance of British Protestant Australia was buried forever.

Shifting Balances with Foreign Policy

Britain’s central role in Australia’s foreign policy shifted fundamentally in the 1940s. Not only did the US ensure Australia’s security in the Pacific theatre during World War II (refer to Chapter 16), but in the postwar environment, Australia’s Attorney-General Doc Evatt played a key role in the formation of the United Nations. Here, he advocated a greater say for ‘small nations’ such as Australia, keeping some distance from larger powers like Britain, America and Russia.

But Australia was far from ready to leave the British embrace. Chifley made the economic and strategic support of Britain a priority in the late 1940s, at the expense of Australia’s economy and his own popularity.

Giving a voice to all nations in the UN

Herbert Vere ‘Doc’ Evatt was attorney-general and minister for external affairs between 1941 and 1949. Before that, he had been part of NSW Premier Jack Lang’s Labor government from 1925 to 1927 and then a High Court judge in the 1930s. In the 1950s, he would be Labor’s opposition leader (after Chifley died in 1951), but it was his work as minister for external affairs in the 1940s that was the highest achievement of his career.

In 1945, Evatt went with deputy Prime Minister Forde to San Francisco as delegate to the United Nations conference and, once there, showed Australia was capable of speaking with a voice quite distinct from Britain’s. Evatt advocated that small- and middle-ranked nations should have much greater say in the new organisation than had been originally conceived by the major powers of Britain, Russia and the US. He managed to get greater powers for smaller nations written into the UN Charter, and was able to ensure a strong commitment to full employment was also included.

Choosing between America and Britain

Even though Curtin had made his famous ‘look to America’ statement in 1942, and American armed forces rather than British forces used Australia as a base from which to launch a counterattack against Japan in World War II (refer to Chapter 16 for more on this), loyalty to Britain still loomed large in Australia in the 1940s.

Before Chifley brought in Australian citizenship in 1949, the majority of Australians surveyed — 65 per cent — said that they would prefer to be classed as British rather than Australian in nationality. People stood up to sing ‘God Save the King’ before films began in cinemas, and at concerts, plays and sports events. Maps in school classrooms showed all the parts of the world (including Australia) that were part of the British Empire coloured in pink. The oath of loyalty at state schools ran ‘I love my country, the British Empire; I salute her flag, the Union Jack’. The sense of British kinship in postwar Australia still ran incredibly strong.

However, after World War II, Britain was destroyed as an economic powerhouse and Australia was no longer able to depend on Britain for defence or trade. America, meanwhile, was beginning to expand its economic interests and investments, and its reach into overseas markets.

Which way would Chifley choose to go? Surprisingly, the fiercely Labor man with a streak of Irish Catholic belligerence chose loyalty to Britain.

Like most Australians, Chifley instinctively saw Australia as part of an alliance of British peoples who were stationed in different parts of the world. In fact, he managed to shock British cabinet ministers in London in 1947 when he declared that only the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Australia ‘fully represent the British tradition and outlook’. At the time, the British Labour Government were trying to engineer a new vision for the Commonwealth, one that included non-white, non-Anglo subjects of the old Empire as equal citizens in the new Commonwealth, and Chifley’s cheerful statement was about as politically incorrect as you could get. But most Australians would have nodded their heads in automatic agreement.

Chifley’s sense of loyalty to Britain was shown to be stronger than the attraction of a closer alliance with America when he asked, ‘Are we to ignore the plight of the United Kingdom because some temporary customer [that would be the US] requires these goods and is prepared to pay dollars for them? Are we to deprive our greatest customer, friend, and ally of these goods?’

While Australians may have agreed with the sentiments behind Chifley’s actions, they didn’t always agree with the actual actions. Chifley’s insistence on supporting Britain involved maintaining petrol and food rationing in Australia long after they’d ceased to be necessary. Chifley argued that the more Australia restricted consumption of butter, sugar, meat, clothes and building materials, the more that could be sent to Britain. This proved increasingly unpopular and, ultimately, was one of the policies that brought about the downfall of the Labor Government in 1949.

A big irony can be found in the perception of Labor versus Liberal governments in the postwar era. Chifley’s successor as prime minister, Liberal Bob Menzies, was both renowned and notorious (depending on your point of view) for being ‘British to the bootstraps’. At the same time, the Labor Party was renowned and notorious for being, if not anti-Britain, at least more independent in its policy. Yet it was Labor’s most beloved leader, Ben Chifley, who wounded his own Labor Government by insisting that helping Britain came before meeting Australian needs.

Treading On an Ants’ Nest — of Angry Banks

Labor had always dreamed of nationalising the banks (putting them under government ownership). This dream had gathered strength during the financial crises of the Great Depression, when many in the labour movement blamed banks for obstructing Labor Government attempts to improve conditions and provide work for the unemployed, through refusing to extend any more credit and insisting existing debts be paid back.

In 1945, a reasonably mild piece of legislation on banking introduced by the Chifley Government contained one inflammatory element — making it compulsory for all levels of government to do their banking with the government’s bank, the Commonwealth. This legislation was challenged in the High Court and overturned. Chifley then decided to be done with half measures and set out to nationalise the banks. More than any other single issue, this move cost Labor power.

Taking a tentative step

The Banking Bill and Commonwealth Bank Bill, from 1945, resulted in some five months of debate in parliament before they were both passed into law. The bills were meant to give the Commonwealth Bank more power as a central and reserve bank.

The Banking Bill was challenged in the High Court by the City of Melbourne. The brilliant young lawyer Garfield Barwick made a case against Section 48 of the legislation, which prohibited private banks accepting any business from a state or local government authority. Surely, Barwick argued, that interfered with the states’ ‘implied immunities’ doctrine, which outlined the states’ spheres of powers and which the High Court used in interpreting the Constitution. The judges agreed with him.

Going full-steam down the nationalisation road

The Saturday after the High Court ruled against the 1945 Banking Bill, Chifley met with his cabinet to decide what to do next. The High Court seemed to be saying the Commonwealth couldn’t insist on what banking was done where, unless the government took over the whole field of banking for themselves. ‘All right then’, said Chifley (or something like it), ‘how about we nationalise the blighters?’

Chifley went round the table getting everyone else’s opinion. Everyone agreed with nationalising the banks. Then they got to Chifley, and someone jokingly asked where Chifley stood. Chifley replied, ‘With you and the boys. To the last ditch’. And to the last ditch it turned out to be.

In October 1947, Chifley brought in the Bank Nationalisation Bill, which made government acquisition of the business, assets and shares of private banks compulsory. When introducing the Bill, Chifley spoke powerfully, summing up the Labor philosophy for socialising key structures in the economy (which had, after all, been part of their party platform for decades). Chifley said the banks had been to blame for the unsustainable 1920s boom and the 1930s bust. Since ‘the money power’ was so great, he said, the entire monetary and banking system should be controlled by public authorities ‘to meet the needs of the people’, just as with the supply of gas, water and electricity. Private banks would be eliminated entirely.

As leader of the opposition, Robert Menzies was in a bit of a bind. After all — who likes banks? Plenty of ordinary people had feelings towards banks ranging from the mildly negative to the vengefully angry after the Depression era. Menzies figured that a ‘save your great friends, the banks’ campaign wouldn’t get very far, so he broadened the argument. Menzies declared that this was the thin end of the wedge — the banks might be brought under government control today, but tomorrow all the neighbourhood milk bars, farms or fishing boats might be taken over. No business would be safe. The banks were happy to pour money into this campaign as well, and promptly did so. But people didn’t need much encouragement to be afraid — it seemed like bad old Labor was re-emerging with plans to make Australia socialist.

Ultimately, the argument was settled again in the High Court. Barwick, arguing against Attorney-General Doc Evatt, said that the crucial aspect was Section 92 of the Constitution. Put in place to protect the right to trade across states, Barwick said this was ‘a constitutional guarantee to the people of a right of immunity to the individual against sweeping government action. It is an individual freedom to move from place to place and the section protects the right to conduct business across state lines’. He won the day. Labor appealed to the Privy Council in London, but they refused to overturn the High Court’s ruling.

This final judgment was given at the end of October 1949, just days before the federal election. In the election campaign, free enterprise versus state control became a big issue. Menzies didn’t exactly romp it in, but he won enough parliamentary seats to form government.