Is the Universe Thinking Through Us?

One of the most admired organizations in the world is Doctors Without Borders, whose courageous members travel to the world’s trouble spots bringing healing. It would be inspiring if disputed borders gradually dissolved around the globe, but the most embattled borders are mental, and they are the ones that need to dissolve first. Everyone, even the most open-minded among us, is trapped behind such borders.

Let’s say you are reading this chapter sitting outside under a tree on a sunny day. You lean back against its rough, cool bark to think. In order to have such thoughts you need red blood cells coursing through your bloodstream; that’s how the brain gets the energy it needs to think. You also need the sun, without which life couldn’t exist on Earth. You need the tree, because without photosynthesis, animals that breathe oxygen would never have appeared. Doesn’t this mean that the tree and the sun are as much you as your blood? The boundaries that we’ve set up between mind, body, and the natural world are convenient, of course, and living within boundaries becomes second nature as we all learn to define ourselves as mothers, fathers, children, spouses, or singles when we get home. Yet the cosmos forgot to specialize, so it delivers reality all at once, in a huge messy package.

This fact can be overwhelming (which often drives people back to the comfort of their familiar pigeonholes). It implies that the universe—all of it, not just our cozy corner—is working through each of us. In order for you to take your next breath, the entire universe had to collaborate—you are the growing tip of the cosmos, the fresh spark of life being pushed forward by all that exists, the way the tip of a green needle on a Pacific sequoia is being pushed by the whole forest and ultimately the entire Earth.

Summon the courage to see yourself this way. Put aside any limited definition of who you are, and be without borders for a moment. I propose that it’s not just the physical universe that is acting through you. When you pierce the mask of matter, you realize that the universe is also loving through you, creating through you, and evolving through you. Such a truth is very personal. To accept the spiritual life at all, this truth must be real for you, for it is the connection to a higher reality. Science sees human beings as isolated specks in the cosmos, accidental outcroppings of mind in a mindless creation. Yet mind is the connection that makes spirituality real. As the universe acts through you, it wraps you in the cosmic mind.

How do you know that you even have a mind? Without taking a philosophy course, most people intuitively accept René Descartes’s maxim, “I think; therefore, I am.” But they wouldn’t say the same about a tree, a cloud, a neutron, or a galaxy. Borders are stubborn; walls are thick. What we need is a more unbounded definition of mind that embraces everything.

In his intriguing book Mindsight, Dr. Daniel Siegel, a deeply inquisitive psychiatrist from UCLA, provides just such a definition, and he has gone to the trouble of testing it out. At first he tried to define mind by asking various colleagues (all of them presumably had a mind), but no one could give him a satisfactory answer. Siegel was particularly interested in qualities of mind that could not be ascribed to the brain, and he found one: the mind’s ability to observe. How we are able to observe the world is one of the greatest of all mysteries. If you try to claim that the brain is the same as the mind, you must answer a simple question: none of the ingredients in a brain cell—proteins, potassium, sodium, or water—can observe, but you can; so how did these objects acquire that capacity?

Let’s have a writer explore the mystery in eloquent fashion: “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking. Recording the man shaving at the window opposite and the woman in the kimono washing her hair. Someday, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed.” The setting is Nazi Germany. The speaker is the nameless narrator in Christopher Isherwood’s haunting short novel Goodbye to Berlin, whose characters would become famous in the movie musical Cabaret. The speaker stands in for Isherwood himself, who wanted to keep truth alive by becoming an objective observer of history as Hitler plunged Europe into the horrors of a second world war. But certain facts work against Isherwood: the eye isn’t a camera. The brain has no photographic images inside it. Perception is a function of consciousness, so the mind comes first, before any physical apparatus—eyes, ears, or brain. That’s why Isherwood says “I” am a camera.

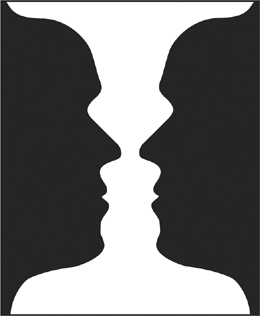

Clearly Leonard’s basic allegiance lies with fixed mechanisms. He offers eye-catching optical illusions to prove that some things are seen the same way automatically, no matter how hard you try to see them a different way. To me, optical illusions prove exactly the opposite. Here’s a classic example:

What do you see in this picture—a white vase standing in the middle of the image, or two faces in black silhouette looking at each other? Both are possible, and the whole point is that you can decide which one you want to see. You can switch from one to the other at will. As with every aspect of being an observer, the process is mental.

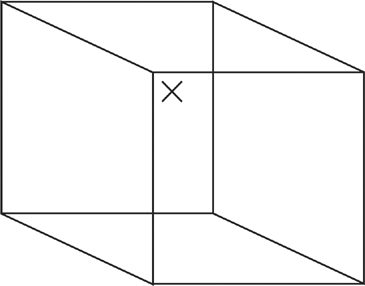

If perception came down to a physical mechanism, a camera, there would be no choice involved. The brain would take a snapshot, develop the image, and print it out. In fact, the brain does none of those things. It is set up solely to represent the mind, which sees, interprets, picks out details, chooses different viewpoints, etc. Presented with an optical illusion, your mind has the ability to see from at least two different points of view. For a second example, stare at the X in the diagram below.

If you see the X as close to you, then it is on the front of the box. If you see the X as far from you, it is on the back of the box. You are the one making this choice; your brain isn’t making it for you. Leonard’s optical illusions were selected to force you to see in a fixed way. But that’s because the brain is a fallible organ. For example, the visual cortex has a specific region devoted to recognizing faces, but it cannot recognize faces that are upside down. Try this yourself. Take a photo of a famous movie star and present it to a friend but turned upside down. Your friend won’t be able to see that the photo is of Elizabeth Taylor or Robert Redford. However, the mind knows how to overcome this fallibility. It can look for clues, even in an upside-down photo—for example, spotting Bob Dylan’s distinctive frowzy hair or Captain Hook’s eye patch. Then it becomes possible to override, at least partially, the limitations of a physical organ.

The brain can limit the mind, of course. If you should happen to have a blinding migraine or a brain tumor, you might not be able to see images at all. Certainly your visual cortex isn’t set up to register ultraviolet or infrared light, as bees and snakes can. So physical limitations do count. They just don’t provide proof of what the mind can and can’t do.

Getting back to Daniel Siegel and his quest for a definition of mind, he made a good choice in settling on our ability to observe, and in particular on the mind’s ability to observe itself. It’s impossible to imagine a computer that can meditate and, by doing nothing else, arrive at insights and breakthroughs, much less change its wiring—but we can do both. Siegel eventually devised his own definition of mind, and having presented it to scientific audiences since 1993, he has met with no objection. The mind, he says, is an “embodied and relational process that regulates the flow of energy and information.” That’s a mouthful, but what makes Siegel’s definition watertight is that not a single term can be omitted. Let’s break it down one word at a time.

“Embodied”: The mind makes itself known through an organ of the body, the brain.

“Relational”: Our minds reflect the environment around us. We are constantly being shaped by the people around us, responding to their habits, speech, gestures, and facial expressions.

“Process”: Mind is an activity. It isn’t static but dynamic.

“Regulate”: The jumble of data that the universe produces would be chaotic unless something organized it into a coherent reality. To keep reality intact, each part must be regulated with every other part.

“Flow”: There is an uninterrupted stream of consciousness to parallel the uninterrupted stream of external events.

“Energy”: To keep the flow going takes energy, at all levels from the immensity of the Big Bang to the micro level of ions passing through the cell membrane of a neuron.

“Information”: Every piece of data can be seen as information, containing a bit of meaning.

What’s so apt about these terms is that you can apply them to every aspect of Nature. As proud as we are of being human, mind is present in an amoeba, a mouse, a neuron, and a distant galaxy. Information and energy flow everywhere; they must be processed and distributed; their activity forms a tight web that connects everything in existence. As a universal definition of mind, this one is hard to improve upon.

Now we have a basis for asking if the universe is thinking through us, or to be more personal, through you. The answer is yes. It’s such a simple answer that in my experience almost nobody resists it. In front of audiences I begin by pointing out that solid objects are deceptive. In reality, everything in the universe is a process with a beginning, a middle, and an end. “Photon” and “electron” aren’t nouns, as far as Nature is concerned; they are verbs. Next I ask the audience to look at themselves.

Are you, too, a process in the universe, with a beginning, a middle, and an end? They nod yes.

Is your brain part of the process? Yes.

Is the electromagnetic storm in your brain giving rise to thoughts? Yes again, and we are almost there.

Then is the universe thinking through you? Most people have no trouble answering yes. If the universe can light up the sky with jagged arcs of lightning on a humid summer night, it can set up the lightning storms that appear on brain scans. In the present chapter all I’ve done is to define “thinking” as a process of mind rather than of brain, and most people don’t object to this, either.

I grew up in an observant Jewish family, so I was surprised one day when my mother told me that she didn’t believe in God. I asked her to explain, and she said that she used to believe, but she couldn’t reconcile God with her experience of losing her family in the Holocaust. On bad days, I remember that I know what she means.

It was years ago, and I had just dropped my son Nicolai off for his fourth day of kindergarten. I stopped on my way to the subway to speak to another parent. I heard an odd sound and looked up the street to see a jumbo jet heading my way, but flying so low it felt eerie. A second or two later it passed overhead, seemed to bank slightly, and quietly penetrated the ninety-fifth floor of the north tower of the World Trade Center a short distance away. Almost immediately the upper floors spewed fire. The thunder of the crash came a half second later, as it would have if lightning had hit. The street broke into chaos, and the air filled with screams, and a rain of fiery debris. What haunts me most is the thought of the ninety-two people I saw obliterated in that moment—my involuntary feeling of connection with those people I never knew, but whose last moments staring out their windows in terror I can’t stop imagining. Nicolai, his five-year-old face apparently pressed against the large picture window in his nearby classroom, saw it all, too, including those who leaped from the roof to avoid being incinerated.

Deepak wrote that we humans are “the growing tip of the cosmos, the fresh spark of life being pushed forward by all that exists,” and that the universe is loving through us, creating through us. He says that “to accept the spiritual life at all,” that truth must be real for us. In taking the point of view of science, and rejecting Deepak’s version of spirituality, I sometimes find myself feeling like the haggard and unshaven Humphrey Bogart sending away beautiful Ingrid Bergman at the end of Casablanca, offering up my cold, calculated assessment that the problems of us little people—and our feelings—don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy universe. But if Deepak is right about a universal consciousness, and that the universe is loving through us, then it must also be hating through us, murdering and destroying through us, doing all the things that humans do in addition to loving, including the acts that blew up my mother’s faith in God. Deepak avoids talking about this dark side, but if the universe is working through each of us, then this universal connection must be a double-edged sword.

Though I believe in neither the God of the Bible nor the immaterial world Deepak advocates, I don’t agree with him that to embrace the scientific view is to turn my back on spirituality. The great physicist Richard Feynman lost his childhood sweetheart, and the “great love” of his life, to tuberculosis when they were in their twenties, just a couple years after they had married. He once told me that he was not angry about it, because “you can’t get angry at a bacteria.” How rational and scientific, I remember thinking. But I later learned that he also wrote a letter to her—more than a year after her death:

D’Arline,

I adore you, sweetheart.… It is such a terribly long time since I last wrote to you—almost two years but I know you’ll excuse me because you understand how I am, stubborn and realistic; and I thought there was no sense to writing. But now I know my darling wife that it is right to do what I have delayed in doing, and what I have done so much in the past. I want to tell you I love you.

I find it hard to understand in my mind what it means to love you after you are dead—but I still want to comfort and take care of you—and I want you to love me and care for me.…

Richard Feynman was not only one of the greatest physicists in history, he was also famous among physicists for his passionate insistence that all theories be closely connected to experimental observations. Feynman felt lucky to have met his soul mate, even though he knew that what they felt for each other could be traced to physical processes, just as her death could be traced to a bacterium. And even though he knew she wasn’t really there with him, he felt Arline’s spirit through all the ensuing decades, until the day he himself died. That love is a mental phenomenon governed by the laws of nature he studied didn’t diminish the depth of Feynman’s feelings, or make him any less spiritual in his approach to life; and that he didn’t really know what it meant to love Arline, or want her to love him, after her death, didn’t cause him to deny that love. He knew that the effort to understand the mysteries of nature, of our mind and our existence, would never bring him in conflict with what he felt in his heart. Indeed, penetrating those mysteries is one of the ultimate triumphs of all the qualities that make us human.

As Deepak says, science draws borders; scientists believe it does that for good reason—to exclude from our worldview that which is not true. But there is plenty of room within those borders for emotion, and meaning, and spirituality. A scientific and a spiritual life can exist side by side.

Is the universe thinking through us? Even in our speculations, we scientists are careful. We want to see our ideas quoted in journals like Physical Review and Nature, not the Encyclopedia of the Wrong. As often happens when questions are posed in words rather than in precise mathematics, the scientific answer depends on the definition of terms. In chapter 14, I described the computational theory of mind. If by “thinking” one means, as some do, computing, then yes, the universe is thinking, because all objects follow mathematical laws and hence their behavior embodies the results of the computation dictated by those laws. Physicist Seth Lloyd wrote, “The universe is a quantum computer,” and we are all part of it. In that sense I could agree with Deepak that we are all part of a universal mind, and that the universe is thinking through us.

But when Deepak argues that the universe thinks through us, he means more than that. He sees us all as connected through a universal consciousness imbued with wonderful qualities such as love, and presumably also its opposite, hate. Embedded within this consciousness, somehow, are our immaterial minds, which express themselves through and also control our physical brains. As evidence of that view, he offers the faces/vase image below.

He says your ability to choose whether to see the two faces in black silhouette or the white vase is evidence that the mind is not a physical mechanism, for a physical mechanism can only “take a snapshot, develop the image, and print it out.” He says that the nonphysical mind, in contrast, “interprets, picks out details, chooses different viewpoints, etc.” But Deepak is wrong about your degree of control in the vase/faces illusion. You cannot choose to see either the vase or the faces. There is no immaterial mind that can overcome the structure of the physical brain.

Try it. If you keep looking long enough, you’ll find that—whichever object you choose to focus on—your brain overrules your choice and flips a visual switch, so that now you see the other object. For example, if you focus on the vase, you cannot indefinitely make your mind consider the space around it as dead space, and not interpret it as two faces. Some people with mood disorders have very long switch periods, minutes compared to seconds, but everyone switches (researchers haven’t relied on people’s self-reports to know this; people’s switching can be measured using external instruments).

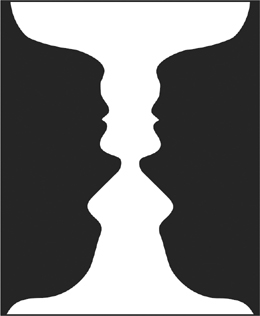

Your visual experience when you look at a “bistable” image like this depends on many factors, such as conscious effort, prior exposure to the image, and its particulars, such as shading, but it also depends on limitations imposed by your physical brain. For example, scientists who studied people as they observed this image found that when subjects are experiencing the faces, but not the vase, a part of the temporal lobe that specializes in face recognition—the specialized region Deepak mentioned—is active. That area, called the fusiform face area, relies on the face being in a normal orientation, and as Deepak said, its efficacy is greatly diminished if you see a face that is, say, upside down. Flip a face over, and the hypothesized immaterial mind should not be fooled, but the physical brain will behave differently. So here is a test: look at the inverted faces/vase image below. Since your brain is in charge, you’ll find the face images less conspicuous than before, but you will still switch perspectives.

In Deepak’s other example he says that if you look at the X in the cube below, you are making the choice of whether to see it at the front or the back of the box. I disagree. So let’s consider a simpler challenge. Armed with the conscious knowledge that the image below is not really a cube, but just some lines on a flat page, command your immaterial mind to take over from your physical brain. Try to perceive what you know are just meaningless lines on a page as nothing more than that. Can you look at the diagram below and not see a cube? If, as Deepak says, your brain is the mere servant of your mind, a camera or instrument your mind uses, while you—your mind—are really making the choice, you should be able to look at the diagram and not perceive a cube. But you can’t.

Deepak employs such examples when he thinks they support his argument and dismisses them when they don’t, saying they arise because the mind is expressed through “a fallible organ.” But that is just the point: scientists have been able to show that every aspect of human thought and behavior that has ever been studied is expressed through that fallible physical organ.

Everywhere we look we see evidence that the mind is a phenomenon of the brain. Daniel Siegel, a professor of psychiatry at UCLA, whose book Mindsight Deepak tries to use as evidence to the contrary, opens the book with a story that very clearly illustrates the physical basis of what we call “mind.” It concerns a family in which the mother, a previously warm and loving presence, was in an automobile accident that severely damaged a part of the prefrontal cortex that is involved in “creating empathy, insight, moral awareness, and intuition.” The result: a person who, while sane and rational and reasonably functional, felt no emotional connection to her family. As she herself described the difference she experienced in her new way of being: “I suppose I’d say that I’ve lost my soul.”

Siegel was brought in to work with the family, for the children were very badly affected by the change in their mother’s behavior toward them. He showed the family a scan of Barbara’s brain and where it had been damaged, so that they would understand that “her brain was broken,” as one of the children subsequently put it. But the other child, not satisfied with this explanation, said, “I thought love came from the heart.” Siegel answered that she was right, and that the networks of cells around the heart and throughout the body communicate directly with the social part of our brain and “send that heartfelt sense right up to our middle prefrontal areas.” But since that was the part of Barbara’s brain that was damaged, it could no longer receive the signals. Over time, the family began to heal, but Barbara never did. Siegel wrote that the “damage to the front of her brain had been too severe, and she showed no signs of regaining her connected way of being.” Her brain was broken, so her mind was, too.

The famous twentieth-century philosopher Bertrand Russell was once asked what he would say if he died and God confronted him, demanding to know why Russell had been an atheist. Russell famously said he would reply that it was God’s fault. “Not enough evidence, God! Not enough evidence,” he would say.

Deepak portrays the scientific insistence on data as cold and impersonal. I would be dishonest to dispute it when he says science sees human beings as “isolated specks in the cosmos, accidental outcroppings of mind in a mindless creation.” There is much in humanity to be thankful for, but to deny that we are isolated specks in the cosmos is to avoid the truth rather than embracing it. Deepak said it takes courage to see ourselves as he suggests we should, but he paints a rosy picture, one that, as in the quote above, he likes to contrast with the worldview of science. What takes real bravery is to embrace the reality we actually observe, without regard to whether it is a bleak or a rosy picture. To grow old, to see friends die and planes crash, and to experience love and loss without the comforting illusion of a living, thinking universe imbued with a divine essence is what takes courage.

At the same time, I do choose a less bleak outlook. To me, though humans might be isolated specks with accidental outcroppings of mind, what is important is that we do have minds, we do have emotions, and we do have the capacity to experience art and beauty and joy. We are made according to chemistry and physics, but we are not “just” chemistry and physics. We are more than the sum of our components, and more than just alive. We are uncaring atoms and molecules that have banded together to care for one another, to feel love—and unfortunately also hate, as well as many other emotions, some exalted, some not. I feel connected. Tiny speck in the vast cosmos that I am, I feel a kinship with all the other tiny specks, and grateful for my brief moment of existence as a physical phenomenon, connected with all the other phenomena in nature. I am glad to be even a small part of an unthinking but wonderful and ever-changing universe.