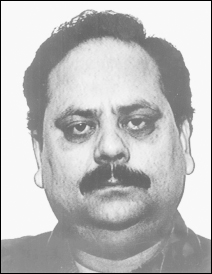

Carl with Brian McLeod after his arrest for trafficking in heroin, Belleville, December 1984.

WHILE CARL WAS SERVING on the hard drug squad and then on the Anti-Drug Profiteering Unit in Toronto, he went undercover on two separate drug cases that involved several native Pakistanis.

The first case began in August 1980, when Sgt. Jim Ewers of the Michigan State Police contacted the RCMP in Toronto requesting assistance in a major international hashish investigation.

Ewers explained that two of his Michigan State undercover agents, Lt. John Shewell and Sgt. Donnie Laskey, had befriended a Pakistani national by the name of Mullah (his last name was never divulged) who promised to introduce them to a big-time Pakistani hashish dealer in Toronto.

Mullah was not a paid informant. He willingly divulged his information to the two Michigan agents because he thought they were in the drug-smuggling game. And he expected to receive a significant fee from both sides for putting a deal together.

As such, Mullah was classified by the RCMP as an “unwitting informant”–one who would be subject to prosecution for conspiracy.

The Michigan Police and the RCMP worked out a plan to have the two Michigan agents and Mr. Mullah fly to Toronto to meet one of the hashish dealers, a Pakistani national named Zaki Pasha. Their objective was to purchase a portion of his huge hashish stash which he had shipped into the port of Oshawa by ocean freighter.

Ewers asked the Toronto RCMP to provide undercover operators to assist his men in this case. He also asked that two Mounties take over the “buy” negotiations in Toronto.

MacLeod’s boss, Staff Sergeant Tom Brown, wanted to use seasoned operators for this investigation, so he offered the assignment to Carl and Constable Nino Sonsini, an experienced constable from the RCMP heroin squad. Both of them were more than willing to accept Brown’s offer.

Carl’s cover story would be that he was a mob-connected, well-heeled drug dealer named Carlo Fudoli who was looking to buy dope in big quantities to supply his distribution syndicate. Sonsini would be his “muscle.”

The American agents were to act as middlemen putting Carl and Sonsini together with the dope dealer.

Carl’s first task was to make arrangements with the DEA liaison officer at the American Embassy on University Avenue to obtain a flash roll of $150,000 in US currency. Then he set up a series of briefings with the RCMP personnel assigned to the case. These included the cover teams who would be following Carl and his partner Sonsini.

When all these arrangements were in place, Sgt. Ewers flew into Toronto on a DEA plane for meetings with the RCMP. The plan they worked out would include over twenty Mounties.

On August 20, Agents John Shewell and Donnie Laskey accompanied Mr. Mullah on a Republic Airlines flight out of Detroit that landed at Pearson Airport.

While the plane was in the air, Carl and Nino Sonsini drove separate cars to the Bristol Place Hotel on the airport strip. Two other RCMP cars followed them. When the police vehicles arrived at the hotel, they gathered together in a distant corner of the hotel’s parking lot.

Carl got out of his vehicle and deposited the $150,000 flash roll in the trunk of one of the RCMP cars.

The driver of that car left it and joined another Mountie in a second car parked about forty yards away. Their assignment was to “sit on” the flash roll money and make sure it was secure. Both of these Mounties were armed with 12-gauge shotguns.

Then Carl, Sonsini, and their cover teams went into action. Each cover team was composed of eight Mounties in four cars. Their jobs were to follow MacLeod and Sonsini in relays wherever they went.

MacLeod and Sonsini proceeded to Pearson Airport, where they waited at the arrival gate for Agents Shewell and Laskey and Mr. Mullah to clear Customs and Immigration.

Among the crowd waiting at the arrival gate, they spotted Zaki Pasha, whom they recognized from a description provided to them by the Michigan State Police agents.

Carl and Sonsini watched and waited for Mullah and Pasha to greet each other.

Carl says, “Mullah was thirty-five and he looked sleazy. He was small . . . no more than five seven and 165 pounds . . . dark and unshaven, which gave him a swarthy look.

“Zaki Pasha was the opposite. He stood out in the crowd. He was the picture of prosperity . . . like a model . . . with dark features and a fashionable beard. Pasha was neatly dressed in a tan shirt and coordinated slacks. He looked to be in his early thirties . . . about six feet tall, maybe 185 pounds.”

Carl and Sonsini moved in to meet Mullah, Pasha, and the two agents.

As soon as the group finished with their introductions and preliminary talk, Carlo took the lead role in making the business arrangements. He knew the routine he wanted to use to keep the game simple and get the job done.

Carlo told Mullah and Zaki Pasha that he would take Pasha away to a nearby hotel and show him the money to confirm his good faith. Carlo said that while they were gone, Mullah was to wait with Shewell and Laskey in the Aeroquay Lounge at the airport.

The two American agents didn’t agree with Carl. Wanting to be in on the buy, they suggested other arrangements whereby everybody would leave the airport together so they could all do the deal in a hotel somewhere.

Carl could sense mass confusion arising from their suggestion. He could foresee the cops tripping over themselves–saying the wrong things and making mistakes–which would complicate everything and jeopardize the sting. He wanted to keep the operation as simple and straightforward as possible.

Much to the American agents’ surprise, Carlo firmly disagreed with them. “Look . . . we’re doing this my way or we’re not doing it at all.”

Shewell and Laskey were taken aback by MacLeod’s aggressiveness but, faced with Carlo’s ultimatum, they agreed to wait with Mullah in the airport lounge.

Before Carlo could leave, Mullah took him aside and told him not to talk price with Zaki Pasha

“Do not negotiate with him. Just give him $98,000 . . . no more. Then I will need to be paid $24,000 for putting this sale together.”

Carl knew Mullah’s crooked game but he didn’t hesitate to agree.

Carl says, “Mullah’s demands are an example of the old saw that there is no honour among thieves. Pasha didn’t know anything about the price being fixed at $98,000. And he certainly didn’t know that Mullah was going to charge a $24,000 commission to broker the deal.

“What’s more, I had been told that Pasha had already promised to pay Mullah a finder’s fee from Pashas’s end of the deal. Mullah was greedy and trying to squeeze money from both ends.

“But I didn’t care. None of that mattered to me because they were all going to jail anyway. So I agreed.”

After Carlo’s brief consultation with Mullah, he, Sonsini, and Zaki Pasha got into Carlo’s car and headed for the parking lot at the Bristol Place Hotel.

Two cover team cars were not far behind.

When they got to the hotel, Carlo opened the car trunk and showed Pasha the $150,000. Pasha was pleased and told them they could have eighty-two pounds of hashish today and more the next time they did a deal. He told Carlo that he went to Pakistan five times a year and sent shipments back to Canada each time. He said he hoped they would have “a long-term arrangement.”

Once again, Carlo agreed.

When the three men returned to the others waiting at the Aeroquay Lounge, Carlo told them that Sonsini was going with Zaki Pasha to get the hashish and they would all meet later at the Bristol Place Hotel to pay the money.

Before Pasha left with Sonsini, he asked Carlo whether or not he’d be interested in buying 90% heroin at $30,000 US a kilo. Carlo told him he would think about that after this deal was done.

As Sonsini and Zaki Pasha drove away from the airport to pick up the hashish, Sonsini’s cover team swung into action behind them. Their four cars, working in relays and communicating by radio, followed Pasha as he drove towards the dope cache at his brother’s home in Scarborough.

While Sonsini and Pasha were gone to get the goods, Carlo and the others had lunch at the Aeroquay Lounge. As they ate, two members of Carl’s cover team sat a few tables away sipping soft drinks.

When lunch was over, Carlo, Shewell, Laskey, and Mullah proceeded to the Bristol Place Hotel. On the way, Carlo asked Mullah if the hashish was good stuff.

Mullah replied, “It’s right out of the kitchen, man.”

Every word he said was captured in a recording device under the dash.

As they drove along the airport strip, Mullah, sitting in the front seat, snorted a spoon of cocaine.

“You want some, man?” he asked Carlo.

“Not right now,” Carlo replied.

Meanwhile, on Brook Mill Blvd. in Scarborough, Sonsini waited in his car for Zaki Pasha to emerge from his brother’s house with the dope. As soon as Sonsini saw Zaki come out of the house carrying the bags of hashish, he did the “Carol Burnett thing” by pulling his ear. This signalled a heavily armed, five-man RCMP take-down team to move in and arrest Pasha. After they had him handcuffed and secure, they raided his brother’s house.

By this time, an hour had elapsed and back at the Bristol Place parking lot Mullah began to freak out because Pasha and Sonsini had been gone so long.

Carl recalls, “He was a paranoid personality to begin with, but he became even more so from the cocaine he had been sniffing. He was getting so crazy that Laskey finally suggested Mullah should phone the cache location in Scarborough and find out why there was such a delay.

“We were sure that our guys had grabbed Pasha by then so we didn’t care what Mullah found out on the phone.

“So we all went into the hotel lobby and Mullah made a call. When he came back to us after the phone call, his eyes were as big as saucers. He told us that someone had answered the phone and said he was a policeman.”

That’s when Mullah really went wild. He cursed at Carlo, blaming him for setting him up and accusing him of being a cop. To back Mullah off and cool the situation, Lieutenant Shewell got into the act and started accusing Carlo too–yelling at him and pushing him in the chest. He was doing this to impress Mullah so that neither Mullah nor Pasha would discover that he was a narcotics agent. If they did, the two Pakistanis would spread the news and jeopardize the State Police’s other ongoing investigations back in Michigan.

Very quickly the scene between Carl and Shewell began to get physically ugly.

“Shewell was a great big guy . . . six foot six and about 260 pounds, and he was really causing a scene in the lobby. He was shoving me and screaming that he was going to get a gun and kill me. And I was yelling back at him and shoving him and telling him that I had a gun and I was going to use it.”

The hotel lobby was packed with travellers who were disturbed by the yelling and frightened by their aggressive physical contact. When the hotel staff threatened to call the police, Carlo and Shewell decided they better move their act outside.

Outside the hotel, Shewell changed his tack. He and Laskey tried to convince Mullah that they should all get out of Toronto immediately. But Mullah wouldn’t buy that. He said he wasn’t going anywhere until he found out what had happened to his buddy, Zaki Pasha.

Finally, to chill Mullah out, Laskey volunteered to call the same phone number that Mullah had tried earlier. He went back into the lobby looking for a phone. Then, about five minutes later, Laskey came running out and announced, “The goddamn Mounties are there. Let’s get the hell out of here!”

Mullah didn’t need any more convincing. Everyone raced for Carlo’s car.

As Carlo drove Mullah and the two Michigan undercover agents back to the airport, everyone in the car was exchanging insults with someone else, each of them accusing the other of being a police fink.

Carl says, “It was really bedlam in that car. But down inside myself, I was laughing my ass off.”

During the RCMP raid on the Scarborough house, the Mounties also arrested Zaki’s twenty-three-year-old brother Pervez and charged him with trafficking.

Carl remembers, “That night was quite a scoop . . . eighty-two pounds of hashish were taken off the street and two big-time drug importers put in jail.”

While the Pasha brothers waited for trial, they spent about $20,000 on lawyers’ fees. When their money ran out, they applied for legal aid but were turned down. That caused them to plead guilty.

They were sentenced to the penitentiary for three years and, as soon as their sentences expired, they were deported back to Pakistan.

“The sentences seemed too short to me,” Carl claims, “but, when you think about it, it’s not such a bad idea. Why should we feed those crooks any longer than we have to? Why not get them out of Canada as soon as possible. The more I thought about it, the more I liked the idea.”

The second case involving Pakistanis occurred four years later when Carl was a sergeant in the Anti-Drug Profiteering Unit.

That investigation began when undercover operator Constable Cal Laurence brought some intelligence to Carl’s boss, Superintendent Les Holmes.

Cal Laurence was a black, ex-amateur heavyweight boxer who was born and raised in Halifax. A big man weighing 240 pounds, Cal had served in the Halifax Police Department before joining the RCMP.

Carl says, “I used to see Cal a lot in the gym on the third floor at headquarters. He was in great shape. He loved going in there and working out on the speed bag.”

A Belleville Detachment Drug Section informant had introduced Laurence to a twenty-seven-year-old soft-drug dealer named Brian McLeod.

McLeod was a bodybuilder and had the reputation of being a local tough guy who bragged about all the weapons that he owned. According to the RCMP informant, McLeod also had a quantity of heroin that he was sitting on until it brought the right price.

At that time, it was quite unusual for someone to have heroin in a small community like Belleville, so the Mounties thought McLeod would be a good target to pursue.

To get the ball rolling, Cal Laurence asked McLeod for a sample of his stuff. McLeod complied and when he did that, the game started to get serious.

Laurence approached Carl MacLeod and explained the essence of the investigation to him. Then he asked, “Are you interested in doing this case in Belleville?”

Carl was always interested in working undercover. But this case was all the more appealing to him because, as a member of the Anti-Drug Profiteering Unit, he was always looking for opportunities to seize criminal assets that had been acquired from the sale of drugs.

Carl very quickly accepted Laurence’s invitation to the dance.

The first opportunity Cal had to bring Carl into the picture occurred when Brian McLeod made it known to Cal that he was looking for another investment partner to help him buy the Dutch Mill Tavern in Trenton.

The Dutch Mill was a good-sized restaurant/tavern that had seen better days. But it had a lot of potential. Ideally located on the Bay of Quinte, the Dutch Mill was a regular hangout for a small cadre of local clientele. McLeod felt that the customer base could be expanded. All the place needed to become a solid money-maker was some renovation money and a little tender loving care.

Brian McLeod and his two partners wanted to buy the Dutch Mill and turn it around. To raise his end of the money for the venture, Brian McLeod needed to sell his supply of heroin.

Laurence told McLeod he knew a well-connected member of the Toronto mob named Carlo Fudoli who was looking for a place like the Dutch Mill to launder some of his illegal money.

Initially, McLeod was not interested in selling his heroin to someone he didn’t know.

But Laurence eventually was able to persuade McLeod that Carlo Fudoli could be trusted. He agreed to a meeting with the Toronto mobster.

The Mounties held preliminary meetings to develop their strategy. Sergeant Dave Unsworth, the man in charge of the Belleville Detachment, and Cpl. Jim Grimshaw, who was assigned to handle the McLeod file, discussed the case with Cal Laurence and Carl.

They felt the best approach was to have Carlo avoid introducing the topic of his buying the heroin. They wanted Carlo to emphasize his interest in investing in the purchase of the Dutch Mill Tavern. Once that connection was established, Carlo could slowly shift his interest to the heroin.

Cal Laurence contacted Brian McLeod to set up a meeting.

On January 30, 1984, Cal Laurence introduced Carlo Fudoli to Brian McLeod in the Whiskers Bar at the Sun Valley Motor Inn, a motel located just off Hwy 401 in the city of Belleville.

Laurence left the meeting almost immediately. Carl had instructed him to do that so he could focus directly on McLeod.

Brian McLeod was physically impressive. As a heavy-duty weightlifter, he was two hundred pounds of solid muscle. This caused him to carry himself in the stiff-necked, rigid-legged gait so peculiar to weightlifters with bulging sinews.

Otherwise he was not so impressive. He had little education and few marketable skills. By his own admission, he worked at an insignificant job as a stock clerk in a local mall. But he clearly saw the Dutch Mill as his big opportunity to better his income and become somebody of significance.

Carl was in his best mobster mode. He drove to the meeting in a new Lincoln Continental, wore an expensive suit and tie, and flashed a lot of gaudy jewellery. He was also carrying a big chunk of cash–just in case a buy opportunity came along.

Carlo spent much of his time hinting that he was a made-man who was connected to the Toronto mob. And he made it abundantly clear that his financial resources were extensive.

It didn’t take long for McLeod to zero in on the main topic on his agenda.

Carl recalls, “McLeod spent a lot of time trying to convince me to come in as a partner on the Dutch Mill. He claimed he had checked its books for the last ten years and everything looked good.

“He also said he had a friend on the Trenton town council who told him that a new airport was being considered for the area, and this would increase the value of my investment.”

Carlo told him he was very interested in the Dutch Mill because he had been looking for a quiet, low-profile business outside of Toronto where he could launder some of his dirty money.

“I told him the deal would only work for me providing his two other partners were willing to look the other way and stay out of my end.”

McLeod replied, “Don’t worry about that. Believe me, none of them are angels.”

McLeod went on to explain that the Dutch Mill was on the market for $700,000. He and his two partners would make an initial offer of $500,000 and he wanted Carlo to put up $50,000.

He also said their plan to increase revenue included the idea of bringing in strippers.

As a ruse, Carlo responded to that by saying, “You don’t want to hire any of the Outlaw Biker Strippers. I know those guys. Once they get in, they’ll take over everything and you’ll lose the place.”

Carlo also outlined some of the procedures that he would use to launder his money through the hotel.

Their conversation went on for over an hour. Eventually, Brian McLeod became so comfortable that he was the one who introduced the idea of Carlo buying some of his heroin.

He introduced the subject by obliquely referring to his supply of dope as “real estate.” When he finally got to the point of offering it for sale, he said, “So Carlo, are you interested in buying some of my ‘real estate’ or not?”

MacLeod made out like he was not totally surprised by his question, “Well, yes . . . I might be able to help you there.”

“Good. How much are you looking for?”

“Could be a lot. I’m looking for a steady source of good stuff. If the quality is right, I’ll take a lot of it.”

“Just give me a little notice and I’ll get you all you want.”

“I wouldn’t mind taking some back tonight.”

“How much do you want?”

Carlo said he was prepared, then and there, to buy a quarter pound of heroin for $24,000.

McLeod said he would get it for him immediately.

Then Carlo asked if he could buy a full pound later on.

“No problem,” McLeod replied, “as long as I have some lead time.”

McLeod went on to explain that his partner was a Pakistani living in Canada whose “people” imported their heroin directly from Karachi five times a year.

“McLeod told me that he didn’t really agree with the idea of selling heroin but he was determined that he wasn’t going to work the night shift stocking shelves for the rest of his life.

“I told him to put me in touch with his Pakistani contact because, if he was going to be running a hotel, he shouldn’t be taking the risk of dealing directly with a drug supplier. McLeod didn’t react to my suggestion. He indicated we should meet behind the hotel at 11:00 p.m. Then he left to get the heroin.”

When McLeod returned with the quarter pound of dope, Carlo did a Marquis field test on it to confirm that it was heroin. This test involves snapping open a small chemical vial and pouring it on a tiny amount of the heroin.

When the powder turned blue, Carl knew it was the real thing.

McLeod was impressed that Carlo carried such testing apparatus with him.

Carlo paid him the $24,000 cash and they agreed to meet some time later. Before they parted, they exchanged phone numbers. Carl’s, of course, was his safe number at Toronto Headquarters.

Two weeks later, Carlo met McLeod in the evening at the Sun Valley Motor Inn.

Much of their preliminary conversation focused on the purchase of the Dutch Mill Restaurant.

McLeod said that one of his partners in the proposed purchase of the hotel was an East Indian named Abdul Majid, whom McLeod had met through his hashish dealers from Montreal.

Eventually, Carlo turned to the topic of his buying more heroin. He told McLeod that the sample he had bought was excellent and the quarter-pound purchase had been only a test to determine the quality of the product.

“I told him I was very pleased but I wanted a steady source who could provide a pound or a kilo on short notice.”

“I can get you pounds and pounds of consistent quality all the time,” he said.

From their conversation, Carl could tell that McLeod was a big-time hashish dealer but he was not so familiar with buying and selling heroin.

“He bragged about the quantities of hashish he had sold and boasted that he was one of the few traffickers in the Belleville area who hadn’t been caught.

“But it was clear to me that McLeod was not experienced in dealing with heroin. There was a lot he didn’t know or wasn’t sure about. So I decided to use his inexperience in that area to get me directly connected to his Pakistani source.

“I told him he needed to be very careful with the heroin he bought from his suppliers. I said, ‘If they ever short you with poor quality goods and you sell it to a major distributor, you could get yourself killed.’

“I strongly suggested that if he didn’t know the quality of the goods he was buying, he would be wiser to put me together with the Pakistanis and then he could concentrate on buying and running his hotel.”

But McLeod wasn’t ready to do that. He presented every argument he could to convince Carlo that the Pakistanis would not meet with him.

But Carlo wouldn’t back off.

“Finally I told him if he wasn’t going to connect me with the Pakistanis, I was going to look for another hotel to invest in. That got his attention and he started to come around.”

McLeod asked Carlo, “If I make the introduction, can you guarantee me you’ll invest in the hotel?”

“You can count on it,” Carlo assured him.

“Okay. We got a deal.”

Minutes later, they hopped into Carlo’s white Lincoln and headed for the Dutch Mill Tavern in Trenton.

“He wanted me to look the place over with him,” Carl says. “And from that time on, I knew we were in for some major arrests in Belleville.”

However, en route something happened that sent shivers down Carl’s spine.

As they were driving slowly through fog and a light rain in a residential area, a five-year-old boy came running out of a Becker’s milk store and darted out onto the street in front of Carlo’s car.

Carlo slammed on the brakes but cringed when he heard the car hit the little boy with a thud.

“I felt sick to my stomach at what had happened and started to get out of the car to check on the little boy.”

McLeod grabbed Carlo by the arm. “C’mon, man, let’s get out of here. No one has seen us.”

“He was prepared to leave that little kid lying on the wet pavement. I couldn’t do that, but I was in a jam. If I was the bad mobster I made myself out to be, I would have taken off like he said.

“But I couldn’t do it. I told him to get out of the car and go. I said I’d tell the police that he was a hitchhiker who I didn’t know who got out of the car and ran.

“McLeod didn’t hesitate for a second. He opened the car door and took off running.”

Carl got out of the car and was relieved to hear the little fellow crying and asking for his mother. Carl’s cover team had been following the Lincoln and witnessed the accident. As soon as they saw it happen, they got on their radio and had an ambulance on the scene in minutes. As it turned out, the boy was not badly hurt. He was taken to the hospital and released forty-five minutes later.

But Carl still cringes at what happened that night. For years, he had nightmares about the sight and sound of his car hitting that little boy. And to this day he has never forgotten McLeod’s callous disregard for the child’s life.

But at that time, Carl was satisfied that the boy was all right. And he had to press on with the investigation.

During the next few weeks, there were several phone calls back and forth between Carlo and McLeod. During the last call, McLeod told him that his heroin supplier was Abdul Majid, and he had arranged a meeting between Carlo and Majid for Monday, February 20.

This was the opportunity that Carl had been waiting for. He knew this was the key to blowing the case wide open.

He also knew that this might be his one and only session with Majid so he wanted a recording device installed in his Lincoln and made arrangements with headquarters to have this done.

At that time, Carl was driving back and forth to Belleville from his home in Burlington.

To install the recording mechanism, RCMP technician Cpl. Art Bowen came out from Toronto and met Carl in an isolated area of a truck stop located off Hwy 401 near Trenton. It took Bowen only fifteen minutes to affix a device about the size of a man’s fist under Carl’s dash. Then Bowen wished Carl good hunting and headed back to Toronto.

At 3:50 p.m., Carlo met McLeod, who was sitting alone in the Whiskers Bar at the Sun Valley Inn.

“Where’s your partner?” Carlo asked.

“There’s been a slight problem.”

“Like what?”

“They only want to front a pound at a time for the first few times.”

“Yeah . . . and?”

“Well, if this is acceptable to you, he’ll meet you and discuss business.”

“It’s not what I’m looking for but . . . all right . . . for the first few times we’ll just do a pound at a time.”

“Good. I’ll be right back.”

McLeod left the bar to make a phone call from the lobby. He was only gone a few minutes before he came back.

“Okay. He’ll meet us in the parking lot out here in ten minutes.”

“Fine,” Carlo replied. Then he nonchalantly asked the waiter for a coffee and carried on with some idle chatter with McLeod.

Carl was playing it cool on the outside but within himself he could feel his heart pounding. He knew he had a big fish on his line and was about to reel him in.

In ten minutes, as promised, Abdul Majid arrived in the parking lot. He was a tall, trim, dark Pakistani in his late thirties with graying hair and a mustache.

Carl says, “I watched him leave his car and get into my undercover vehicle and the one thing I remember about Majid is that he wore a sad expression on his face . . . almost a permanent scowl.”

After McLeod introduced them, Carlo and Majid briefly engaged in some preliminary conversation and then got down to business.

Majid said they would only sell him one pound at a time. And in response to Carl’s request, Majid told him that his Toronto “people” would not agree to meet with him at this time.

“No, not now,” Majid said. “Maybe later . . . when they know you better.”

“Okay, that’s all right with me,” Carlo replied. “My only concern at this time is that I have a reliable source who can supply me with quality merchandise.”

Majid assured Carlo that he was the man to do that. Then he told Carlo the price for this pound of heroin was $85,000.

Carlo objected strongly to that price, insisting the pound should cost no more than $60,000. He said, “There’s no deal with me at that price.”

This was a calculated risk that Carl had to take. If he agreed to Majid’s inflated price, the other side would know he was paying too much for the dope and smell a rat.

“No real drug dealer who knew the market would pay that much more for a pound of heroin. I had no choice but to turn the deal down.”

Majid didn’t know what to do or say. He just stared at Carlo with his dour expression.

Carlo continued, “Look, man, why would I pay that? If I can’t make any money on this deal, I’m not interested.”

Majid said he understood Carlo’s position but this was the price his people wanted and he couldn’t sell it for less. He said that he was unhappy too because his end of the deal–his commission–was only $5,000. He even went on to whine about how badly he wanted to get out of the drug business.

“I got a wife and three kids. I don’t want to be doing this . . . taking chances like this any more.”

“That’s a problem you’re going to have to solve for yourself,” Carlo told him. “But at the price you just quoted me, the deal’s off.”

Majid said he would check things out and get back to Carlo. They agreed to meet again if Abdul could get the price in line.

When Majid departed, Brian McLeod was really upset that the deal had gone sour. He suggested that Majid was lying about the price. “He’s trying to grab a big piece for himself. He just wants to get rich fast.”

But he also told Carlo that Majid’s people were having trouble. “They just lost a five-pound shipment in New York City and they’re very nervous about making deals with buyers they don’t know.

“I’m pretty sure he’ll come back with a better price. But we’ve got to be patient. If we’re going to make this work, we got to go very slow.”

During the next month, McLeod phoned Carlo several times and tried to assure him that things were looking promising.

They met again on April 10 in Carlo’s wired undercover vehicle in the parking lot behind the Sun Valley Motor Inn.

McLeod advised Carlo that he had an agreement to buy the Dutch Mill Tavern for $530,000, and the closing date for acquisition was June 3. He was going to need to get Carlo’s end of the investment within a month.

He reported that Majid’s people were presently in Pakistan arranging another heroin shipment and they would definitely have some to sell to Carlo. He also asked if, in the meantime, Carlo wanted to buy his last three ounces of heroin.

“Actually they belong to Majid, but I get a commission for selling them. So what do you . . .”

McLeod stopped his sales pitch when he spotted two men sitting in nearby cars. He was sure they were RCMP narcs, and for the next few minutes, he stopped talking and watched their every move.

Carl had seen this paranoia in every drug dealer he had dealt with.

“They are all convinced that they’re being followed twenty-four hours a day.”

McLeod relaxed only when the two men got out of their cars and headed into the restaurant.

Carlo said he would pass on McLeod’s three ounces and wait to purchase a pound from Majid. Playing on Majid’s previously perceived need and greed, Carlo asked McLeod to tell Abdul that he would pay him good money for an introduction to his Toronto connection.

On the morning of May 2, Carlo phoned McLeod at work and told him he was just returning from Montreal and wanted to meet him for an update on the hotel and “other business.”

At the end of their meeting, McLeod suggested they go and meet Majid at the Belleville factory where he was employed as a welder.

At the noon meeting outside the plant, Majid made promises about delivering a pound of heroin at a fair market price. Abdul also claimed that his heroin connection had been badly spooked by the RCMP when the Mounties visited his Toronto house on an immigration matter.

Further, he divulged that his Toronto connection operated a Pakistani grocery store on Gerrard Street to which the heroin was imported. It was smuggled into the country hidden among shipments of East Indian spices.

Abdul encouraged Carlo to buy McLeod’s three ounces of heroin, because most of the money from its sale belonged to him and he still owed his people for previous purchases.

That meeting made it evident to Carl that both Majid and McLeod were operating on a shoestring and were desperate to put a big deal together to turn their lives around. And he knew their desperation was his biggest advantage.

During the return drive to the Sun Valley Motor Inn, Brian McLeod concluded that Carlo didn’t want to touch the three ounces of heroin for fear of getting caught with it in his possession. So he offered to deliver it personally to Carlo in Toronto.

He told Carlo he had no trouble doing that, because the risk of carrying three ounces was minimal compared to the fifty pounds of hashish he often transported in the trunk of his sports car.

“That’s no problem for me, “McLeod bragged. “I got that Trans Am so souped up, I can outrun any cop car on the road.”

Carlo told McLeod he would probably buy Majid’s last three ounces of heroin from McLeod, but not right now.

“I’ll let you know later,” he said. “But when I buy, I will want us to transact the deal through couriers.”

“That’s okay with me.”

The three-ounce purchase took place on Thursday, May 24, at the Dutch Oven Restaurant on Hwy 115 north of Hwy 401. Carlo’s partner for the sale was Cpl. Earl McClare, a very experienced undercover operator, who acted as Carlo’s courier. He would receive the heroin directly from McLeod’s courier.

When Carlo met McLeod in the restaurant at 12:30 p.m., he emphasized that he was only buying these three ounces as a personal favour to him and Majid because of the much bigger deals that lay ahead.

He asked McLeod if he had spotted any “heat” on his way from Belleville.

McLeod said he hadn’t seen any, and his “friend,” who had the dope outside, had ridden his motorcycle from Belleville at very high speeds.

“I can assure you he wasn’t followed.”

Carlo and McLeod walked outside to witness the dope exchange.

On Carlo’s signal, McClare approached the biker who pointed to his helmet on the ground.

After McClare retrieved the three ounces from inside the biker’s helmet, McLeod told Carlo that this was a bargain-basement price only for him because they figured he would be their major steady purchaser.

Carlo asked McLeod where he should meet Majid to pay him the $9,000 for the three ounces of heroin.

McLeod suggested Oakville.

“Why Oakville?”

“Because Abdul lost his job in Belleville and got one on the assembly line at Ford’s in Oakville. So now he lives in Oakville.”

“Okay. You set up a meeting for us there.”

The sale transaction was a satisfying moment for Carl, because that gave them enough evidence on both McLeod and Majid to arrest them for trafficking.

But there were still bigger fish to be caught.

The Mounties’ efforts to locate Majid’s suppliers in Toronto were going well.

Toronto RCMP had identified the Toronto store owner and two other connections and wiretapped their telephones. One of the parties was a Pakistani national named Misbahul Hassan.

Just days after the three-ounce delivery at the Dutch Oven on Hwy 115, a call was intercepted at Hassan’s residence from Abdul Majid warning the Toronto suppliers to be careful because he was convinced that the RCMP were on to them.

Carl was shocked by the substance of that phone call.

“We couldn’t figure out why Majid thought that. Everything was going smoothly. I was positive he didn’t suspect me as a cop. We had no reason to believe he suspected anything. But something had really gone wrong and we needed to find out what it was.”

Their investigation revealed that an office worker at Ford’s had tipped off Abdul that the police were asking about him.

“It was a complete fluke. In an effort to determine the location of Abdul’s residence in Oakville, an RCMP member had approached the personnel office at the Ford Motor Company and asked for Abdul’s address.

“A young Pakistani woman working in the office heard about our inquiries. She didn’t even know Abdul Majid but she phoned him at his house and warned him that the police had been in the office asking questions about him.

“When Majid learned about that, it compromised our investigation. But, at least, our wiretap told us that Majid knew we were after him. We were determined to forge ahead with the investigation; we just had to play it differently.”

Carl was prepared for McLeod when he called and said that Abdul was screaming that he had some “heat” and was convinced that Carlo was a cop.

Carlo screamed back at McLeod that he too had had “heat” from the cops. He told him that his courier from the Dutch Oven was stopped on the highway and it was only because the cop was lazy that he hadn’t searched him and found the three ounces of heroin

Carlo continued with his rant: “I wish I was a fucking cop, because then I wouldn’t be going crazy here with worry. I don’t know what the hell is going on but we’ve got to back off. We got to sit tight for a while till this shit blows over. Call me right away if you hear anything else.”

McLeod wasn’t totally assured of Carlo’s innocence but agreed he would phone him if he heard anything more from Abdul.

Carl knew this was a crisis and was convinced he had to do something dramatic to keep the investigation alive.

To prove he was running away from the police in Toronto, he drove to his cousin Fred Burk’s place in the Sunday River ski area near Bethel, Maine.

Then, calling from a telephone booth so he could claim that the cops couldn’t trace him to a specific residence, Carlo phoned McLeod and told him to go to a telephone booth in Belleville at 9:00 that night and call him back at his Maine telephone booth number.

That night, Carl went back to his telephone booth and waited for McLeod’s call. At 9:05 p.m., the phone rang.

After their hellos, McLeod asked, “Where the hell are you?”

“In Maine.”

“Where in Maine?”

“Never mind.”

“What are you doing there?”

“There was too much heat on me in Toronto. I had to get out of there. I’m going to hunker down here for a while until things cool off in Toronto.”

“Okay. I understand.”

“Have you had problems with the cops?”

“No, I’ve been okay. But Abdul is still scared shitless. He’s not sure if you’re the cops anymore, but he’s convinced that it’s the Immigration that’s chasing after him.”

“Well, I don’t know anything about his immigration problems. I just want the cops off my ass. You tell Abdul that as soon as he feels things have settled down, I will pay him the $9,000 that I owe him for the three ounces. And tell him that I need at least another pound right away.”

“Okay, I’ll tell him. When are you coming home?”

“I don’t know. Not for a while . . . not until I feel safe. I’ll phone you when I get back.”

“Okay.”

“Be careful.”

“Okay.”

Carl felt that McLeod believed him. He could only hope that things were back on track and the investigation could still be saved.

Carl returned to Ontario and phoned McLeod on June 29. By then, McLeod had found another money partner and completed his purchase of the Dutch Mill Tavern. But his finances were tight and he still needed money to cover his end. Consequently, he was still very interested in selling Carlo heroin.

Much of their conversation was about Abdul. McLeod said that Abdul was still seeing “ghosts.” Abdul wanted McLeod to get a hold of Cal Laurence, the undercover operator, who had put everything together in the first place, to check and see if Carlo was a cop.

Carlo insisted that McLeod try to get Abdul settled down.

Finally, Carlo asked for Abdul’s phone number. McLeod, who desperately wanted everything to work out between the three of them, gave Carlo the number.

When Carlo phoned, Abdul was very disturbed to receive the call. He insisted that any future business had to be done through McLeod in Belleville.

“Abdul had made up his mind that I was a cop and no amount of persuasion was going to change his mind. I decided to lay low for a while and let the situation cool down. But I wasn’t going to let it die.”

Three months later–in October–Carlo showed up unannounced in the bar at the Dutch Mill in Trenton. McLeod wasn’t there when Carlo arrived, but he did show up shortly after that. When he spotted Carlo, he approached his table with apparent apprehension.

He started out by complaining in an unhappy tone that Abdul was still freaked out about Carlo phoning him at home.

Carlo nodded that he understood, but before he could say anything, McLeod asked him, “You’re not here to arrest me, are you?”

Carlo assured him he was not and invited him to sit down. Then, slowly and cautiously he drew McLeod into more pleasant conversation. Their discourse went so well that McLeod eventually had one of his strippers come out and give Carlo a private performance on stage before any of the regular dinner crowd arrived.

After she finished her routine, McLeod suggested that he and Carlo go out someplace for dinner where they could talk privately.

When they went outside, McLeod was very impressed with the luxury model BMW that Carlo was driving.

During dinner, Carlo told McLeod that to avoid the “heat” he was now living in Hammond, Indiana. He also advised him that a friend of his was expecting a large shipment of hashish.

Without hesitation, McLeod said he would buy thirty pounds of it.

When they split up at the end of the evening, Carlo gave McLeod a “safe” phone number for McLeod to reach him in Indiana. Carl had made technical arrangements within the Hammond DEA office so that any phone call received at that number would automatically be forwarded to Carl’s safe phone in Toronto Headquarters.

Carl was convinced that this would be their last social time together.

“We knew we had McLeod and Majid solid, and, by then, because of our wiretaps, we had the Toronto connections, too. Now it was just a matter of keeping in touch with them until we had enough intelligence to make the biggest possible drug seizure.”

In early December, the Mounties decided to move. They swooped in and arrested McLeod in Belleville, Majid in Oakville, and Misbahul Hassan in Toronto. They also nabbed three other minor players involved in Hassan’s criminal enterprise.

During their raids, the RCMP seized heroin with a street value of one million dollars and 150 pounds of marijuana worth $90,000.

Carl was at the Belleville RCMP office when Majid and McLeod were being processed for arrest. They had already been given their caution, but Carl wanted them to know that they were right all along–he truly was a policeman.

After showing them his badge and his ID, he said, “Just so there is no misunderstanding, when I appear in court at your trials, I am Sergeant Carl MacLeod of the RCMP. And you are both under arrest for trafficking in heroin.”

Neither of them made any response.

Majid couldn’t look at Carl. He knew what lay ahead. First he would be sent to prison, and then he and his entire family would be deported to Pakistan. The good life that he sought for his children was lost forever.

McLeod, the egomaniac, was in shock. Standing with his head bowed in the detachment, he was a far different man than the swaggering braggart who had claimed to Carl that the police would never catch him.

The trials for the six heroin dealers took place in Toronto and Belleville.

Carl with Brian McLeod after his arrest for trafficking in heroin, Belleville, December 1984.

Carl with Abdul Majid after his arrest in Oakville; photo taken in Belleville, December 1984.

McLeod received an eight-year term in the penitentiary. The Anti-Drug Profiteering Unit took a hard look at seizing his prized hotel, but McLeod and his partners owed so much money on the mortgage that the place essentially belonged to the bank.

Majid and Hassan received less prison time than McLeod, but that was because they were ordered to be deported to Pakistan after their sentences expired.

The McLeod-Majid case had gone on for a year and had involved a great deal of expense and a considerable amount of human time and energy. Carl MacLeod alone had spent hundreds of hours nurturing the principal players and plotting their arrest.

Misbahul Hassan, the Gerrard Street store owner who was arrested in December 1984.

The case hadn’t gone perfectly. There were lots of bumps along the way. Mistakes were made that threatened to scupper the investigation. But with a little ingenuity and a lot of persistence, the Mounties were able to stay the course and bring the investigation to a successful conclusion.

Carl’s final comment on this case is appropriate: “There’s an old adage that the police like to quote among themselves: ‘We have more time than the bad guys, and we can afford to make more mistakes.’”