bar 3

Blues Conditions

FROM BLACK TO WHITE

For more than two decades I’ve been teaching a college-level course called “The Blues Tradition in American Literature.” At some point early on, I came up with a two-page handout headlined “Teaching the Blues: A Few Useful Concepts for the Classroom.”1 In the next several chapters, I’m going to explore those concepts, beginning with something I call “blues conditions.” Before I do that, I’d like to reprise a little cultural history.

If there’s one idea that can help us make sense of the current state of the blues, it is aftermath. (In this respect, we might take a cue from Toledo.) As American blues people, black and white, we are living in the long aftermath of slavery and segregation. Early in the new millennium, we’re still working through the traumas that those related but distinct epochs inflicted on America’s African American residents, and we’re still conjuring with the African roots and creole contours of the blues’ musical inheritance. But we’re also living in the aftermath of a more recent series of changes that transformed blues music and blues audiences during the 1960s, especially in America. What happened during that decade still critically shapes the contemporary blues scene and the tensions that inform it.

Between 1920 and 1960, more or less, blues music was black popular music. This is true whether we’re talking about blues queens like Bessie Smith and Dinah Washington, or urbane city bluesmen like Charles Brown, Leroy Carr, and B. B. King, or the Mississippi-to-Chicago axis that gives us Charley Patton, Jimmy Reed, and Muddy Waters, or R&B bandleaders like Wynonie Harris and Louis Jordan. In 1952, a Louisiana-born bluesman named Little Walter had a #1 R&B hit for eight weeks with “Juke,” a harmonica instrumental. In 1952 blues was big. It was a music where young black men with talent and ambition like Walter, Jimmy Rogers, and Muddy Waters dreamed big dreams. The film Cadillac Records (2008) gives you some sense of what it was like to be a young Chicago blues performer in the early 1950s.

Then rock ’n’ roll shows up. The rock revolution happens at Chess Records in the summer of 1955, when Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry have #1 hits with “Bo Diddley” and “Maybelline.” The Chess brothers suddenly become much more interested in recording Bo and Chuck than Muddy and Walter.2 The white kids are dancing to rock ’n’ roll, and there’s big money to be made if and when the Chess brothers’ black artists cross over. The black kids, too, are quickly beginning to pivot from blues to rock ’n’ roll. By the time we get to 1960, to judge from the #1 hits, blues is beginning to ebb as a black popular music, or certainly as the black popular music. It’s beginning a downward arc, at least among black audiences. With white audiences, of course, exactly the opposite is happening. The British blues invasion hasn’t happened yet, but by 1960 the folk revival is in full swing and white audiences, along with a few white musicians, are suddenly starting to get interested in something called “country blues.” The Country Blues is the title of Samuel Charters’s groundbreaking 1959 study of the music, a book whose deliberate romanticism helps stoke white fascination. The following year, British researcher Paul Oliver publishes Blues Fell This Morning (1960), a richly detailed study that interprets the lyrics of hundreds of blues songs in the context of African American social history to offer a panoramic view of black America’s struggles and triumphs during the long dark night of Jim Crow. The books by Charters and Oliver hit the white audience hard, helping them hear the music as deeply connected with the freedom struggle of the ongoing civil rights movement. But those books also conjure up the blues people, with their forthright sexuality, restless ramblings, and vivid juke joint nightlife, as an irresistible locus of romance, guardians of down-home authenticity and preternatural vitality—and thus the antidote to the uptight world of middle-class white adulthood, the world of the Squares and Organization Men and feminine mystique that the counterculture is gearing up to demolish with an all-points assault later in the decade.

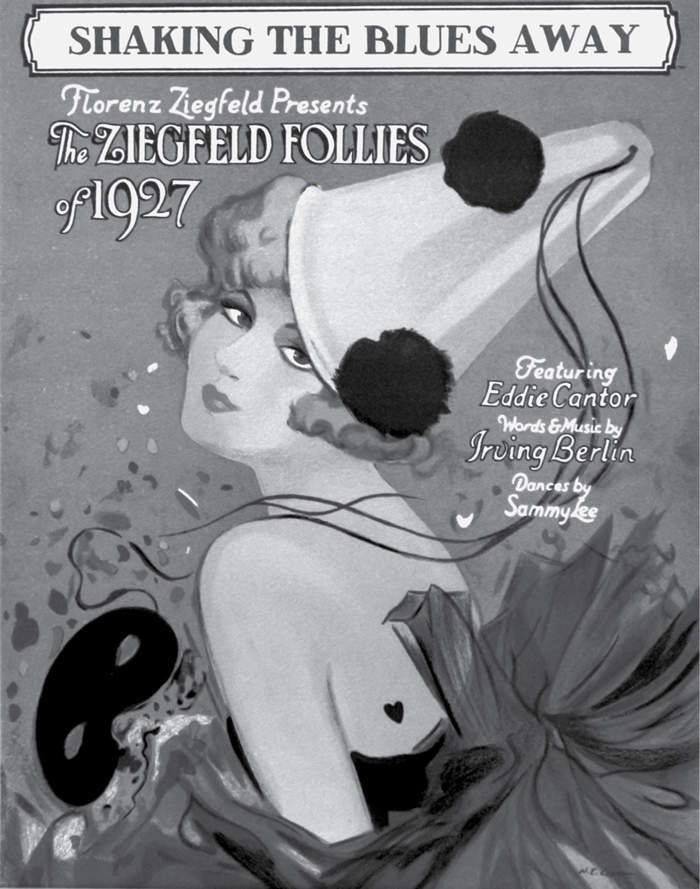

Now, it’s important to acknowledge that there had always been some white audience for blues music. There was a white urban audience for blues queens like Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey in the 1920s, and there was a blues craze of sorts on Broadway during that decade, a time in which Tin Pan Alley songwriters wrote “blues” that don’t really deserve that name. An example of this trend is Irving Berlin’s “Shaking the Blues Away,” a 1927 dance number at the Ziegfeld Follies featuring lines like “When they hold a revival way down south / Every darkie with care and trouble that day / Tries to shake it away.”3 Sophie Tucker, a Russian Jewish immigrant who took lessons in blues singing from African American star Ethel Waters, was billed as both a “coon shouter” and blues singer in the 1920s and given the moniker “Last of the Red Hot Mamas,” paving the way for subsequent white torch singers like Janis Joplin, Bette Midler, and Mae West.4 Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis were singing hillbilly blues in the 1950s, as Jimmie Rogers was singing his “Blue Yodel” songs in the 1920s. White blues, to paraphrase Gil Scott Heron, ain’t no new thing.

Cover of sheet music for “Shaking the Blues Away”

(courtesy Rue Royale)

But those earlier developments are merely a prelude to what happens when white America’s fitful fascination with the blues is powerfully reinvigorated at the beginning of the 1960s. With this white interest, not surprisingly, come misunderstandings and distortions. Given the worldwide stardom that B. B. King enjoyed for the last five decades of his life, it may be surprising to learn that he and Bobby “Blue” Bland were dismissed by many blues aficionados and commentators in the early 1960s as purveyors of a gaudy, commercialized, aesthetically impoverished variant of the “true” blues played by the country bluesmen. It wasn’t until Charles Keil published Urban Blues (1966), one year after the British blues invasion and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band had launched a white blues revolution, that subcultural opinions about King began to change. Spurning country blues advocates as clueless “moldy figs,” Keil made a cranky and convincing case for King and Bland as preacher-like figures in the black community, great blues artists who ministered to their black fans on Saturday night in a way that wasn’t wholly different from what went on in church on Sunday mornings.5 It didn’t hurt that audible evidence for Keil’s claims could be found on King’s 1964 album, Live at the Regal—one of the greatest live blues albums ever recorded, chiefly because it registers the close and mutually sustaining relationship between King and his adoring black fans. But that album also registers something that was rapidly disappearing from the scene: an African American blues performer as black pop star.

By 1968 B. B. King is playing for the white flower children at the Fillmore West—he’s suddenly a huge star with that audience—but young black people are turning away from him to embrace soul music. They think of his blues as backward, “country,” the sound of slavery and submission that their parents and grandparents may have put up with but that they no longer will. The disrespect he suffers at the hands of younger black audiences brings him to tears on at least one occasion. Yet on the night he debuts at the Fillmore, the white kids give him such a warm reception that they, too, bring him to tears. “By the time I strapped on Lucille,” he remembers in his autobiography “every single person in the place was standing up and cheering like crazy. For the first time in my career, I got a standing ovation before I played. Couldn’t help but cry. With tears streaming down, I thought to myself, These kids love me before I’ve hit a note. How can I repay them for this love?”6

The first big blues festival, a white-run event featuring black blues artists playing for countercultural crowds, takes place in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1969 and repeats in 1970. The blues societies that will come to dominate mainstream blues life in the 1990s and beyond haven’t yet happened—the first will be formed by Vietnam vets in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, in 1977—but by 1970 there’s no question that the white blues revolution has arrived. In December 1969 there’s a concert at Madison Square Garden featuring Janis Joplin and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band; one white rock journalist calls it “the greatest blues battle of recent years,” even as black intellectuals fume at the hubris of it all.7 Why and how did this upheaval take place? Where did these white blues audiences and white blues musicians come from? How did black people, the undisputed originators of the music, lose control of the music? What does this loss of control mean for the music? Don’t the music and its social meanings change when it is taken up and used by people who hail from outside the music’s culture of origin?

In order to answer these questions, we need to have some idea of what the music meant to the people who created it. We need to pause for the cause, return to the source, and explore the foundations. We need to do so with a sense of restraint and irony, precisely because that is so rarely how commentators approach the blues. Something about the blues encourages large generalizations, decisive pronouncements, and passionate investments, rather than nuanced claims, as though the music is the audible distillate of Black America’s sufferings since the 1619 landing at Jamestown, or, alternately, a universal solvent that resonates in every corner of the world. Yet the blues’ own epigrammatic tradition encourages restraint—or at least one portion of it does. When Bo Diddley tells us that “You can’t judge a book by looking at the cover,” he’s warning us against jumping too quickly to conclusions about the content of someone’s character, including their musical character, based on surface appearances. Are blues a black thing? Of course they are. How could they not be? Are they a white thing? Well, a whole lot of white folks (and Asian folks) these days sing and play something that they call the blues. If we’re being empirical rather than prescriptive, shouldn’t this matter? But the story of the blues isn’t just the story of who is singing the song, or what they’ve suffered in order to sing it. The audience matters, too. Call-and-response, the reciprocal interplay between a performer and his or her community, is a foundational aesthetic principle of the blues. If B. B. King was so moved by the warm response he received from the white hippies at the Fillmore that he not only burst into tears but delivered what he calls “the best performance of my life,” aren’t the blues—contemporary blues—a black-and-white thing?

FREEDOM NEEDS AND TRICKSTER SENSIBILITIES

If our quest for enlightenment has to begins somewhere, it might begin with the following summary statement from my “Teaching the Blues” handout:

The blues are relentlessly dialectical, foiling any attempt we make to crystallize their truths into one incontrovertible statement. This curious and under-remarked quality has something to do with the freedom needs and trickster sensibilities of the music’s African American originators: a refusal to be either nameless or wholly known, a refusal to be held in place, defined downward by slander, quietly rubbed out.

To say that the blues are relentlessly dialectical means that when the blues show up, they almost always show up not as one thing—one feeling, one spiritual orientation, one musical element—but as two or more things in tension. The blues are country, they’re down-home. But they’re also big-citified, urban. They’re Muddy Waters in Mississippi, driving a tractor through the cotton fields and playing guitar with a sawed-off bottleneck slide—but they’re also Muddy getting off a train in Chicago and plugging his guitar into an amp. The blues are rough like Howlin’ Wolf, but they’re also as smooth and urbane as Dinah Washington. Blues are songs of sadness: I just can’t keep from crying. But I’m also smiling just to keep from crying—smiling on the outside, even when I’m crying, or rage-filled, on the inside.

Blues are songs of sadness transfigured by rhythmic energy into a source of healing. Albert Murray made this point in Stomping the Blues. Stomping the blues doesn’t just mean that we’re going to jump up off the couch and dance our low-down blues away; it also means that we’re going to stomp on those blues and give ’em a beat-down. We’re going to rout them and drive them out the door. Janheinz Jahn made exactly the same point. Blues music, he argued, is designed to conjure up Nommo: “the spoken word, the sound of the drums, the laughter of the throat, the poem, and the song.”8 Blues song doesn’t just reflect low-down blues feelings in a passive way; it summons Nommo, purges those feelings, and creates a mood of uplift. Blues music brings relief from the blues.

Blues feelings are despair backed by euphoria. “I may be down, but I won’t be down always.” But the blues are also euphoria shadowed by despair. Watch out! You may be sitting on top of the world at this particular moment, but one summer day your baby might just decide to go away. Then again, if you’re a skillful blues navigator, you’ll find a way of surviving that disaster, too. “But now she’s gone … and I don’t worry … Because I’m sitting on top of the world.”

The blues are relentlessly dialectical. And this “curious and under-remarked quality” is connected with the “freedom needs and trickster sensibilities of the music’s African American originators.” When I make this claim, I’m speaking to a male tradition within the blues. I’m thinking once again about David Honeyboy Edwards and The World Don’t Owe Me Nothing, a story of blues life in the Mississippi Delta of the 1920s and 1930s. Life in that time and place was dominated by cotton sharecropping. Young black men like Honeyboy were consigned to the cotton fields from the time they were nine or ten years old. Honeyboy got a taste of that life, working alongside his parents and siblings, until Big Joe Williams, an itinerant bluesman, wandered along. Fascinated by Big Joe’s music, Honeyboy got his father’s permission to head south with the older man. The two guitarists, master and apprentice, worked their way down to New Orleans. Williams showed Honeyboy how to “make it”: how to play for tips in the street. At a certain point, when Big Joe got drunk and violent, Honeyboy took off; he worked his way back home, heartened by his newfound ability to handle the streets on his own. By the time he rejoined his family in Greenwood, his vision of life’s possibilities had been transformed. Once he realized he could harvest spare change from the public by playing the music he loved, he resolved never to be a sucker again, picking cotton all day long in the hot sun for a dollar.9

What are the blues? They are a way of self-presencing, self-annunciating. They’re a way of asserting your identity rather than remaining an exploited anonymous cog in a cotton-producing machine. They’re a way of saying “I’m here, baby. I’m a Howlin’ Wolf. I’m a crawling kingsnake and I’ll crawl beneath your door.” They’re about renaming yourself in a bold way, declaring yourself powerfully present. Willie Dixon’s great musical innovation is the stop-time riff that drives “Hoochie Coochie Man.” Da DA-da-da DUH! “I’m the hoochie coochie man, everybody knows I’m here!” Self-presencing is important when you live in a world that has corralled you with vagrancy laws and terrorized you with lynch law, a world that sees you as a pair of hands that should be in the cotton field working hard all day for next to no money, without complaint.

Etched into the blues tradition is the fact that some people found a way out of that destiny. Honeyboy and other traveling musicians are the skilled tradesmen of the blues, men who honored their creative gifts by honing their skills and evolving a free-floating guild that stretched from New Orleans to Chicago. Blues songs tell the truth about this life. I’m going to leave this town, I’m going to catch the first mail-train I see—but if I head out into the great wide world, I’m risking the wrath of those vagrancy laws. I risk being accused of rape if I find myself in a town where there’s no white boss to vouch for me. Living out your freedom demanded a trickster’s sensibility. In other words, even as you’re singing “I’m here!” and making a name for yourself, you’re also finding ways of whispering “I’m not here” and dancing away from the disciplinary net that encircles you.

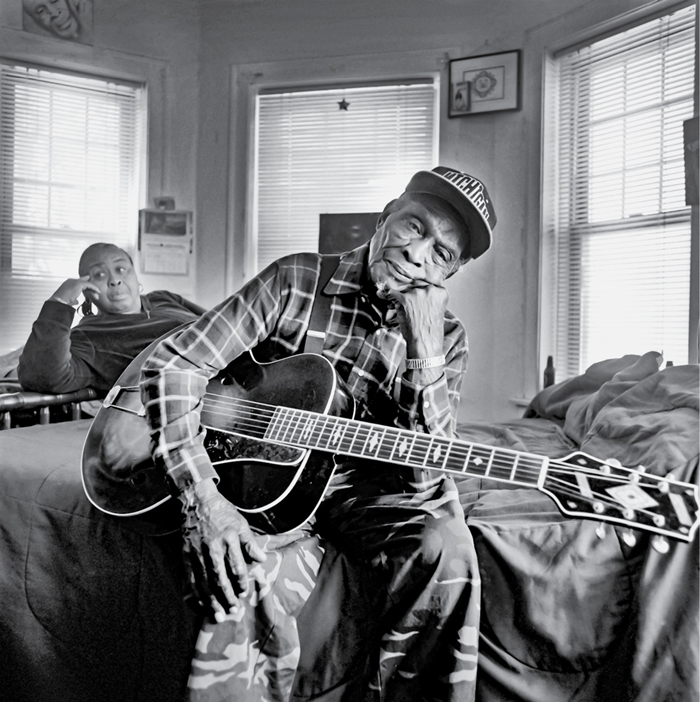

David Honeyboy Edwards, 2008

(courtesy of the photographer, Bill Steber)

Honeyboy shrewdly gamed this element of the blues dialectic. As he roamed the Delta, busking for nickels and dimes, he’d spend the night with a series of different women—one in every town, more or less, and often somebody living on a plantation. He didn’t want to get hooked up to a plow, he didn’t want to sharecrop for a white boss, so he’d stay at a woman’s house for a relatively brief period of time. She’d feed him with leftovers from the white man’s table, sleep with him, give him some money or clothes. As a black man present on a plantation during the work day, of course, he was still fair game—unless he fooled the boss. “The way to get by all that,” he said, “[was to] stay in the house all day long. I was like a groundhog. Come 6:00 I’d take a bath, come out like I’d been in the field. They don’t know whether you’ve been in the field or not then. That’s the way I done.”10 In this manner, he evaded the white boss’s proprietary gaze and retained self-ownership. He escaped what Houston A. Baker Jr. calls the carceral network, the network of laws, customs, people, and institutions that wanted to kill you, imprison you, or merely lock you in place as part of a compliant black labor force.11

Honeyboy’s footloose lifestyle is a strategy of resistance, and it’s organized around a paradox. I’m here, I’m here in a big way, I’m in your face, I’m the show. I’m Honeyboy, the ladies’ man. But the next moment, I’m gone.

BLUES IS, BLUES ARE

The blues is, or are, a devilishly tricky thing to talk about, in part because of such paradoxes. Start with the sentence I’ve just uttered. Do we say “the blues is” or “the blues are”? Is the blues singular, or are the blues plural? It is a strange object of inquiry indeed that oscillates in such a way. Blues is, we might stipulate, a form of music that originates in African American communities in the southern United States. But the blues are also a range of emotions, not just a generalized sadness, and so there’s an undeniable plurality to the blues as well. The blues is a mutable but durable music with a distinctive sound that takes a range of forms as it undergoes a modernizing process, a music that continually renegotiates its relationship with its own traditions.

One of the things that makes the blues powerful is precisely the fact that when we have them, or have very strong feelings about them, we’re sure we know what they are. Yet when people have disagreements about what the blues is, or are, those disagreements often result from the fact that they are confusing or conflating several distinct facets of the blues.

So let’s begin again, very carefully, with a four-part definition that has proven useful in undergraduate classrooms: Blues conditions lead to blues feelings, which are expressed as blues music; the feelings and the music are encompassed by, and the conditions are endured with the help of, the blues ethos.

Blues conditions, blues feelings, blues music, blues ethos. Four interrelated facets of the surprisingly complex social and aesthetic phenomenon known as the blues. Needless to say, most people who talk about the blues don’t dissect the word, or concept, into component parts. Quite the reverse: they tend to use the word expressively, assertively, in ways that blend or blur several elements. They drive on Mississippi’s country roads, see a tumbledown sharecropper’s shack, and say “Now that is the blues.” What do they mean? In an English department, we might say that the material object—the shack—instantiates a specific conception of the blues. It exemplifies and expresses an idea of the blues as something connected with poverty, with beat-downness, with southernness, with blackness. If you live in a shack like that—well, if the weather is cold outside, you’re going to be shivering inside. It’s small and cramped, and since it’s falling down, you obviously don’t have the money to fix it. With a house like that, you’d just sit around in the evening after working all day and feel bad about being poor, or fume at being exploited. Or maybe you’d sit on the front porch, set some rhythm going on a guitar, and sing out those feelings. All those bluesy ideas somehow coalesce around a specific material object, that tumbledown shack.

The declarative statement, “Now that is the blues,” fuses all those ideas about the blues. But we can, if we want, come along and begin to disentangle those ideas. We can talk about blues conditions: the shack itself, cold and dirty and collapsing. We can talk about blues feelings: how you’d feel if that was where you were forced to live. We can talk about blues music: the sort of music you might make if you lived in a shack like that. And we can talk about the blues ethos: a philosophical orientation toward life that might sustain you if you were the guitar-playing, blues-singing resident of that shack.

Let’s begin with blues conditions. What are they? The first thing to be said is that many people conflate blues conditions and blues feelings. That’s not entirely misguided—the two easily intermingle—but neither is it the best way of seeing clearly what is going on. Blues conditions are best defined relationally: they are the material facts and social environment that together constitute the ground out of which blues feelings emerge. Failed love is a classic blues condition. A man loves a woman, makes love to her, and then she leaves him for somebody else. The blues condition isn’t the painful, rip-your-heart-out feelings that this situation tends to incite in such men, it’s merely the fact that a love relationship has ended. Not every failed love, after all, produces rage, jealousy, and despair. I felt all those things when, as a much younger man, I lost my girlfriend of five years to a man I knew. The wounds were bone-deep and lasted for years. But fifteen years later, when a second five-year live-in relationship failed, I felt nothing except exhaustion, disdain, and a desire to move on. As a blues condition, in other words, failed love doesn’t automatically produce a specific kind of feeling in those who suffer or merely experience it. Sometimes you hurt, sometimes you don’t. The conditions and the feelings don’t always coexist in predictable ways—which is why it’s useful, for the sake of careful analysis, to distinguish them.

The blues condition of failed love is universal, a fact that some have used to explain the global popularity of blues music. By the same token, failed love has certain specific implications in black southern working-class contexts that deserve attention. In a place and time where black men were squeezed hard by both sharecropping economics and the daily indignities of Jim Crow, a beautiful and beloved wife or lover was a particularly valuable possession—the most charismatic possession, arguably, that a black working man might claim. The loss, or threatened loss, of such a prized possession took on outsized importance in such a context. Honeyboy Edwards, neither more nor less promiscuous than most traveling blues musicians, understood the danger that indiscriminate promiscuity could engender among jealous local men in the communities he was passing through. “You take some ordinary man that’s working hard,” Edwards insisted, “he’s not a musician, and he’s got a good-looking woman, he don’t want to lose her. Because he figures he won’t find another one like her, he’ll kill you about her. He’d rather be dead than lose her. So I leave that woman alone. When I got older I learned that wasn’t nothing but trouble and death. I learned to leave that alone.”12

“He’d rather be dead than lose her.” There’s a world of feeling—fierce possessiveness, murderous jealousy, boundless despair—evoked in such a sentence. Honeyboy doesn’t body forth the feeling in flowery language, he just acknowledges it, warily, as a blues one would be advised not to inflict, and steers clear. This world of feeling makes more sense if we appreciate the contours of the Deep South world in which Honeyboy and that “ordinary man” were living. The blues conditions they confronted were sociohistorical as well as personal, and the effects of this linkage were profound.

One way of understanding the blues is to say that it’s a music created by people who were comprehensively unloved by the surrounding white world, wanted only for their labor power and the profits that labor power could produce. This was as true for slaves like Honeyboy’s grandmother as it was for men his own age, but with a critical difference that I noted in the previous chapter. When you’re a slave, somebody owns you; they have a material investment in your physical person. Anybody who hurts or kills you is damaging a white man’s property, which puts a check on the violence that other white men other might do to you. After Emancipation, this check on white violence vanished. The apocryphal saying, “Kill a mule, buy another; kill a nigger, hire another,” spoke to this condition of decapitalized worthlessness.13

Love, in such a context, gives a man respite from the killing fields. A lover’s embrace creates a world for you. Failed love, by contrast, strips a man of that comfort and dangles him once again over the precipice. Failed love is indeed a universal blues condition, but it is shadowed, in Honeyboy’s Mississippi, by larger and social ills.

Failed love is a representative blues condition, but my classroom handout lists several dozen others. Unrequited love: I love her, but she won’t love me. And a promiscuous lover: a central theme of the blues, one that shows up in brags, laments, and everything in between. “Checkin’ on My Baby,” “Careless Love,” “I Am the Devil,” “Mustang Sally,” “Bumble Bee.” In Blues Legacies and Black Feminism (1998), a study of women’s blues, Angela Davis attributes the prominence of sexuality as a blues theme to the changed situation in which southern black folk found themselves after Emancipation. A key thing distinguishing a slave from a freedperson is that when you’re a slave, somebody else—your master—is determining who you’re going to sleep with. There were, of course, slave marriages, but they were difficult to maintain. When slaves got married, they often ended up being forced to live on distant plantations rather than being able to live together, an arrangement known as “abroad marriages.”14 When freedom came, it manifested in various ways, including the right to marry and live with whomever one wanted and, alternately, the right to live out an unprecedented sexual license and mobility. The latter was especially true as one descended the social ladder into the places where blues were being played and danced to. The black middle class defined itself as middle class by hewing to standards of respectability that involved marital fidelity, regular attendance at church, chaste dress, abstinence from liquor, and polite conversation, but the blues people let all that go. There was a lot of promiscuity among juke joint folk. Promiscuity is exciting, dramatic. You may not have much money, but if you’ve got a little money, some flashy clothes, the requisite curves (if you were a woman), and a good rap (if you were a man)—well, you’ve got something to work with, and blues people worked what they had.

This gets us to the heart of a blues paradox. Angela Davis says the blues sing of sex because that was one of the principal ways the children and grandchildren of slaves experienced their freedom. But that source of freedom was also a source of pain. If I’m free and you’re free, we’re free to choose each other, and that enactment of our freedom can indeed be wonderful. But you’re also free, if you wish, to play around behind my back. That enactment of your freedom creates emotional anguish for me—an anguish that many would consider a paradigmatic blues feeling.

But here again we’ve skipped ahead to blues feelings when what we were supposed to be inventorying was blues conditions: the interpersonal or behavioral situation within which feelings arise. The reason why we distinguish conditions from feelings is that a given blues condition doesn’t automatically give rise to the expected blues feeling. A lover who cheats on you might lead you to feel an anguished, murderous rage, but you might also feel somewhat liberated; your lover’s faithlessness might license your own misbehavior, your own resolve to get a little something on the side. Not infrequently, blues feelings manifest as a powerful, combustible mixture of negative and positive emotions, a sense of being uneasily suspended between conflicting imperatives. As Kalamu ya Salaam once famously wrote, speaking of blues people, “Life [for them] is not about good vs. evil, but about good and evil eaten off the same plate.”15 There are sweet blues as well as bitter blues, in other words, and bittersweet blues may be the bluesiest blues of all.

A terrific lover: now there’s a blues condition! Many blues songs have been written from the standpoint of a man or woman who wants to sing the praises of the gal or guy who is driving them wild. Little Walter brags of his lover in “My Babe” that “once she’s hot, there ain’t no coolin’.”

Unrequited love, failed love, a promiscuous lover, a terrific lover: all four situations are variants of one specific kind of blues condition: the charged atmosphere created by the dance between lovers. Here’s another variant: the arrival of Saturday night with all of its romantic possibilities. Juke joints, dance halls, cabarets: the spaces of black leisure were critically important for working-class African Americans, both rural and urban and especially in the South, precisely because their laboring lives left them exploited, exhausted, and in need of spiritual regeneration and completion. Saturday night, which might easily last “all night long,” was the week’s one big chance to catch up—to drink, flirt, brag, dance, style and profile, and, with luck, score a lover. The blues tradition offers a number of songs that represent the heady freedoms of club life, from the boisterousness of Willie Dixon’s “I’m Ready” and “Wang Dang Doodle” to Louis Jordan’s “Saturday Night Fish Fry” and Matt “Guitar” Murphy’s “Way Down South.”

JIM CROW SOCIAL RELATIONS

My “Teaching the Blues” handout leaps from the category of love relationships to something that seemingly stands at the farthest remove from love: Jim Crow social relations. When I say Jim Crow, I mean southern segregation: the establishment and maintenance of the color line in the U.S. South; the enforced inferiority inflicted on black southerners through law and custom. In its own way, this is just as central a blues condition as those generated by troubled love; one might even argue that Jim Crow social relations are the ground on which all other blues conditions stand. The forty-year period from 1920 to 1960 in which blues was black popular music happens to correspond with the period in which segregation hardens into what white defenders were fond of calling the “southern way of life.” Segregation doesn’t begin in 1920, of course. It slowly emerges in the 1870s and 1880s as a piecework series of local statutes, and it is first formalized in 1890 with the introduction of the so-called Mississippi plan: a new Mississippi state constitution that disenfranchises the state’s black voters, greatly diminishing the ability of black Mississippians to determine their own future at the ballot box. Other Deep South states follow Mississippi’s lead. At the same time, those states begin to enact segregation statutes—back-of-the-bus laws—mandating separate accommodations in every place where black and white might actually come into social contact. This is the very moment when a generation of upwardly mobile middle-class black southerners are becoming doctors and lawyers and dressing in good Victorian fashion. But the white South says “Get back.” The two worst years for lynching in the South are 1892 and 1893. The moment you prevent people from voting, you can do anything you want to them and they have no legal recourse. That’s what segregation was and how it worked.

The mid-1890s, interestingly enough, are the moment when blues songs start to show up in the American South. One of the best-known witnesses to that moment is W. C. Handy, the self-styled Father of the Blues. I’ll speak at length about Handy later; what deserves mention here is one particular song referenced by Handy, and later adapted by him: “Joe Turner Blues,” with its curious talk about how the “long-chain man” has “come and gone.” Joe Turner was actually Joe Turney, a Tennessee lawman whose job it was to transport prisoners, most of them black, from one prison to another back in the days before motorized transportation. He accomplished his task almost exactly the same way that his predecessors, the slave traders, would have marched slaves from back-country Virginia down to Mississippi in days gone by: on foot, with the prisoners in leg irons, chained together.16 If you’ve read Douglas Blackmon’s Pulitzer Prize–winning study, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (2008), you know how frequently the African American men who ended up chained in those sorts of neoslave coffles were not criminals at all but victims of unscrupulous white men who’d arrested and imprisoned them on the flimsiest of pretexts, generally as “vagrants,” then profited by selling their labor to other men who ran coal mines and cotton fields.

As a blues condition, in other words, the idea-set called “Jim Crow social relations” opens out into more than just separate-but-equal accommodations. It’s a comprehensive set of oppressions that descended on black southerners, particularly men, in the period after 1890s. Suddenly, after being able to vote for several decades after the Civil War, you’re told that you can’t vote. Suddenly black men are being strung up, tortured, and burned publicly in so-called spectacle lynchings, and there is no legal recourse for the wives and families of the victims. If you’re a man, you’re forced to step off the curb in your small town every time a white woman passes. If you so much as look at her, or if she says you looked at her, that’s potentially a lynching offense. Sociologist John Dollard spent the mid-1930s doing research in the Mississippi Delta; in Caste and Class in a Southern Town (1937), the study that emerged from that research, he described the sense of fear that this social tightrope instilled in the black men there:

White people may or may not be very conscious of this threatening atmosphere in which negroes live, but negroes are extremely conscious of it. It is one of the major facts in the life of any negro in Southern town. I once asked a middle-class negro how he felt about coming back down South. He said it was like walking into a lion’s den. The lions are chained, but if they should become enraged it is doubtful whether the chains would hold them, hence it is better to walk very carefully. Every negro in the South knows that he is under a sentence of death. He does not know when his turn will come. It may never come, but it may also be at any time. This fear tends to intimidate the negro man.17

I use the term “disciplinary violence” to convey this sense of overhanging threat, a key element of the segregated world in which southern bluesmen lived and worked. The teaching handout lists not just Jim Crow social relations but also racism, the presence of lynching and vagrancy laws in the social field, and race-based disrespect. All of these related phenomena are blues conditions. But so, too, is disrespect from one’s racial coevals, which is to say, intraracial disrespect. It is hardly surprising that in a world structured by a comprehensive, legally sanctioned disrespect of blacks by whites, black men should be keenly attentive to perceived disrespect from their black peers. This phenomenon was exacerbated by the broad persistence, across the South, of patterns of hands-on vengeance and justice, something that white men and black men actually had in common. When injured or offended in some way, southern men, regardless of race, have tended through the years to take the law into their own hands, seeking immediate retributive justice rather than waiting for the criminal justice system to restore equilibrium.

One of the most powerful evocations of this theme within the blues literary tradition shows up, again, in August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (1984), specifically in the figure of a southern-born trumpet player named Levee. The narrative present of the play, as I described in Bar 2, is a Chicago recording studio circa 1927. Levee is the youngest member of Ma Rainey’s recording ensemble. He’s young, he’s restless, he’s edgy; he’s something like Little Walter in Cadillac Records. He’s a flirt—he’s trying to seduce Rainey’s female lover—and he spends his money on fancy shoes. He thinks that his bandmate Toledo, the historian/philosopher who speaks of black people as “leftovers,” is a fool. Levee is an impatient young hothead, basically, who doesn’t respect anybody. When his bandmates start to rag on him about the way he’s currying favor with Sturdyvant, the record label owner, he starts to get mad. They say, “You don’t know how to handle the white man,” and Levee suddenly fumes. “Levee got to be Levee! And he don’t need nobody messing with him about the white man—cause you don’t know nothing about me! You don’t know Levee. You don’t know nothing about what kind of blood I got! What kind of heart I got beating here!”18

Then he starts to tell a story, one that transports us from the Chicago recording studio back in time and southward to his boyhood in Mississippi. It’s a story about a particular traumatic experience that has marked him irreparably. It’s Levee’s blues: the ground out of which his subsequent emotional and professional life has developed. “I was eight years old,” he said,

when I watched a gang of white mens come into my daddy’s house and have do with my mama any way they wanted. We was living in Jefferson County, about eighty miles outside of Natchez. My daddy’s name was Memphis … Memphis Lee Green … had him near fifty acres of good farming land. I’m talking about good land! Grow anything you want! He done gone off of shares and bought this land from Mr. Halley’s widow woman after he done passed on. Folks called him an uppity nigger ’cause he done saved and borrowed to where he could buy this land and be independent. (68–69)

Honeyboy Edwards escapes the dead-end of sharecropping by grabbing a guitar and rambling widely, but Levee’s father does it the hard way: he manages to scrimp and save enough to buy his own land and “go off shares.” “It was coming on planting time,” Levee continues,

and my daddy went into Natchez to get him some seed and fertilizer. Called me, say, “Levee, you the man of the house now. Take care of your mama while I’m gone.” I wasn’t but a little boy, eight years old.

My mama was frying up some chicken when them mens come in that house. Must have been eight or nine of them. She’s standing there frying that chicken and them mens come and took hold of her just like you take hold of a mule and make him do what you want. There was my mama with a gang of white mens. She tried to fight them off, but I could see where it wasn’t going to do her any good, I didn’t know what they were doing to her … but I figured whatever it was they may as well do to me too. My daddy had a knife that he kept around there for hunting and working and whatnot. I knew where he kept it and I went and got it.

I’m going to show you how spooked up I was by the white man. I tried my damndest to cut one of them’s throat! I hit him on the shoulder with it. He reached back and grabbed hold of that knife and whacked me across the chest with it. (69)

Levee, Wilson tells us, “raises his shirt to show a long, ugly scar.” It isn’t just a bodily injury, it’s the physical manifestation of a traumatic wound to his soul. (The original meaning of the word “trauma” is “wound.”) “That’s what made them stop,” Levee continues.

They was scared I was going to bleed to death. My mama wrapped a sheet around me and carried me two miles down to the Furlow place and they drove me up to Doc Albans. He was waiting on a calf to be born, and he say he ain’t had time to see me. They carried me up to Ms. Etta, the midwife, and she fixed me up.

My daddy came back and acted like he’d done accepted the facts of what happened. But he got the names of them mens from mama. He found out who they was and then we announced we was moving out of that county. Said goodbye to everybody … all the neighbors. My daddy went and smiled in the face of one of them crackers who had been with my mama. Smiled in his face and sold him our land. We moved over with relations in Caldwell. He got us settled in and then he took off one day. I ain’t never seen him since. He sneaked back, hiding up in the woods, laying to get them eight or nine men.

He got four of them before they caught him, before they got him. They tracked him down in the woods, caught up with him and hung him and set him afire.

My daddy wasn’t spooked up by the white man. Nosir! And that taught me how to handle them. I seen my daddy go up and grin in this cracker’s face … smile in his face and sell him his land. All the while he’s planning how he’s gonna get him and what he’s going to do to him. That taught me how to handle them. So you all just back up and leave Levee alone about the white man. I can smile and say yessir to whoever I please. I got time coming to me. You all just leave Levee alone about the white man. (70)

Wilson is evoking a deep and complicated blues here: a young Mississippi-born bluesman in Chicago demanding the respect of his black bandmates not just by baring his own wounds—a mother gang-raped while he watched, a father hung and burned—but by testifying to the spirit of retributive justice against white malfeasance that animated his father and continues to guide him. The southern scene of trauma is carried forward as a black migrant’s fierce creed. But Levee has overestimated his achieved control over the situation. As the play draws to a close, Sturdyvant suddenly announces that he is unable to use the songs he has commissioned Levee to write. “I don’t think I can use those songs,” he says in effect. “I’ll pay you $5 each, but I don’t really think I can use them. I’ll take them off your hands, though.” Aghast, Levee suddenly discovers that he has been played.

The entire play has been constructed, in some sense, to produce the train wreck of blues conditions that now pour down on Levee, flooding him with an explosive mixture of dismay, rage, and humiliation. This is the moment when Toledo, crossing the studio, accidentally steps on his shoe. What should have been the smallest of inconveniences, easily soothed with a quick apology, becomes the last straw, the final insult. “All the weight of the world suddenly falls on Levee,” reads the play’s stage directions, “and he rushes at Toledo with his knife in his hand.” When Levee stabs and kills Toledo, what is he killing? Not just his bandmate but also the black community’s historian and conscience—which is to say, the possibility of full historical consciousness and critical analysis, both of which are desperately needed if the community is to survive and prosper. But black-on-black violence doesn’t erupt out of nowhere, for no reason: that, too, is a lesson taught by Wilson’s play. The southern world out of which these musicians emerge and the northern world in which they’re presently striving to live full and authentic lives are both superintended, “managed,” by predatory white men. Where Levee’s father takes his time to inventory the injury to his family, make a getaway plan, and then exact suicidal vengeance on his white antagonists down in Mississippi, his son up in Chicago simply acts on his feelings, his blues—and slays his fellow black musician, pointlessly.

Blues music is left to bear witness. “The sound of a trumpet is heard,” reads the play’s concluding stage direction. “Levee’s trumpet, a muted trumpet struggling for the highest of possibilities and blowing pain and warning” (111). Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom evokes the blues not just as a poetry of aftermath but also as a lived condition of beleaguerment in which past exploitations and the feelings of rage and powerlessness they engendered in African American subjects continue to haunt the present. And they do haunt the present: not just the play’s narrative present but also our own contemporary moment, one marked by both the Black Lives Matter movement and gang violence in Chicago. Blues conditions endure in black communities, even as the music has moved outward into the surrounding world.