bar 8

Zora Neale Hurston in the Florida Jooks

SEX, VIOLENCE, AND THE CULTURAL INVESTIGATOR

Zora Neale Hurston, the third founding member of the blues literary tradition along with W. C. Handy and Langston Hughes, has arguably played a more complex and multilayered role than the other two. Like them, she was a translator, one who sought textual analogues—words on a page—that could do justice to the bittersweet lyricism, dynamism, and bold self-declarations found in blues music and the people who made and used that music, especially in the rural South during the early decades of the twentieth century. Like Handy, she was born in Alabama, although Florida raised and claimed her; like Hughes, who became a close friend and collaborator, she called Harlem her home during the Renaissance as a member of the so-called Niggerati, an upstart group of younger African American writers determined to think and live freely, reconfiguring the black image in white and black minds alike. Although Hurston has risen in stature since the mid-1970s to become a canonical figure in African American literature, American literature, and feminist studies on the basis of her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), her achievements as a blues-themed writer and folklorist have drawn less attention than they deserve.

The basic outlines of that achievement are easy to sketch. Hurston is the first cultural investigator, male or female, to write of black southern juke joints or “jooks” from the inside, both literally—she spent considerable time in one of them, the Pine Mill in Polk County, Florida—and figuratively, as a black female Floridian whose rural upbringing placed her in close imaginative proximity to the blues people whose songs and lives she was documenting. In both these respects she accomplished something that her widely traveled and intrepid white southern peers, Howard Odum and Dorothy Scarborough, were unable to do. Drawing on that experience, she wrote a major essay (a portion of “Characteristics of Negro Expression” subtitled “The Jook” [1933]), a pioneering folklore study (Mules and Men [1935]), a novel (Their Eyes), and an autobiography (Dust Tracks on a Road [1942]). Because she was a woman, and not an unattractive one, she found herself, as a cultural investigator who fraternized with male musicians and storytellers, drawn somewhat further into the fevered sexual economy of the jook than she had intended. It was a situation that aroused violent jealousies in several local women and equally fearsome threats on her behalf by one specific figure of power, Big Sweet, a swaggering, knife-wielding jook habituée. Both Mules and Men and Dust Tracks narrate versions of the same crisis: the night when her principal antagonist, Lucy, tries to knife her to death and Hurston is forced to flee the Pine Mill—concluding her participant-observation and saving her own life—as the jook erupts in spectacular fashion.

The understandings that Hurston evolved about blues people and their milieu, in other words, were both hard-won and problematic; they offer us a critical perspective not just on the limits of white privilege where certain kinds of cultural investigation are concerned but also on the understandable desire of some contemporary readers to view Hurston as an exuberant celebrant of black southern folk culture rather than a thoughtful and nuanced analyst and advocate who was vividly aware of the shadows that lurked within her broadly comic representations. Handy and Hughes, too, grapple with the violent vitality of southern blues people. Handy fears for his own safety as bandleader at a key moment in Father of the Blues when two of his men, a rougher class of Memphis musicians than he’s employed in the past, start fighting on a parade float in Atlanta. “The band divided into factions,” he remembers ruefully, “attempting to keep one from cutting or shooting the other.”1 Hughes drew the fire of black reviewers for poems like “Suicide” and “In a Troubled Key,” from Fine Clothes to the Jew:

I’m gonna buy me a knife with

A blade ten inches long.

Gonna buy a knife with

A blade ten inches long.

Shall I carve ma self or

That man that done me wrong?

…

Still I can’t help lovin’ you,

Even though you do me wrong.

Says I can’t help lovin’ you

Though you do me wrong—

But my love might turn into a knife

Instead of to a song.2

Hurston, like Handy and Hughes, played a vital role in the emergence of blues literature precisely because she truly did desire to celebrate, defend, and ennoble her working-class black subjects, even as she remained determined—as a cultural anthropologist and novelist—to honor their complexity, unconcerned with how some might judge the resulting portrait. She, like Hughes, was criticized harshly by some readers: not black newspaper columnists and other guardians of racial gentility, as in Hughes’s case, but her black male peers, Sterling Brown and Richard Wright, both of whom insisted that she had egregiously underplayed the trauma that Jim Crow had inflicted on southern black folk.3

Where Hurston differs from both Handy and Hughes is the question of sexuality—a tricky question indeed, given the way black female sexuality had long been haunted by the lascivious Jezebel stereotype. Even as Handy and Hughes write frankly about the frustrated romantic passions out of which blues song emerges, both men expunge their own sexuality from their texts. The father of the blues, remarkably, is a kind of neuter, the opposite of a juke joint playboy. The only trace of sexual passion that he offers in his 1941 autobiography comes during an 1899 trip to Havana in the company of his wife, when he notices “Cuban senoritas” smiling at him from a balcony. “For a moment I was mesmerized by the hocus pocus of lovely dark eyes, red roses and fingers that threw kisses.” Two pages later he reports that his wife, suddenly losing her appetite, has informed him that he “was destined to become a father.” “I’d have excellent reason,” he concludes, signifying on his own role in the pregnancy, “to remember the perfumed influence of sultry Havana.”4 In a blues tradition marked by sexual braggadocio of the crawling-kingsnake, little-red-rooster variety, Handy’s sexual self-presentation is remarkably chaste, as though the blues’ father figure was determined to steer clear of the messy, unruly passions he had taken as his chosen subject—and as befitted a good son of the Talented Tenth who was trying to win the blues broad cultural acceptance. Repressing his own desire in Father of the Blues, he enables white readers to identify with him as a benign elder statesman. Hughes, in The Big Sea and elsewhere, is equally discreet in the matter of his private erotic entanglements. “Only three times in his autobiographical writings would Hughes speak of being in love with women,” notes his biographer, Arnold Rampersad. Although he did occasionally mention having visited prostitutes, his sexual persona was, according to Rampersad, marked by “a quality of ageless, sexless, inspired innocence, Peter-Pan like,” something that led Hughes to be “regarded by many of his friends as asexual, without noticeable erotic feeling for either women or men.”5 Yet his blues poems were, or could be, hot, sexy, and violent. His blues people lived out what he apparently did not.

Hurston is a different story. Although she wasn’t known for dressing in a revealing, hoochie-mama fashion, merely comporting herself with style and the occasional red scarf, she lived a far messier life, in erotic terms, than Handy or Hughes. She was married twice, both time to younger men, and had an extended, on-again, off-again relationship with a man more than twenty years her junior, the model for bluesman Tea Cake in Their Eyes. She put much more of herself into her works, in this respect, than did Handy or Hughes; indeed, she foregrounds her own inadvertent self-staging as an object of sexual interest and jealousy in the juke joint environment, and she confesses with playful astonishment in Dust Tracks that the men she encounters consistently, and mistakenly, see her as a sex object:

They pant in my ear on short acquaintance, “You passionate thing! I can see you are just burning up! … Ahhh! I know that you will just wreck me! Your eyes and your lips tell me a lot. You are a walking furnace!” This amazes me sometimes. Often when this is whispered gustily into my ear, I am feeling no more amorous than a charter member of the Union League Club. I may be thinking of turnip greens with dumplings, or more royalty checks, and here is a man who visualizes me on a divan sending the world up in smoke. It has happened so often that I have come to expect it. There must be something about me that looks sort of couchy.6

Hurston is having fun with the Jezebel stereotype here, deflating it even as she coyly acknowledges her own Cleopatra-like attractions, but she’s also aligning herself to some extent with Bessie Smith—whom she knew and admired—and other blues queens of her era: strong, independent, self-actualizing women who sang signifying songs full of sexual double-entendre and boldly pursued their passions. Writing of her extended affair with Percival McGuire Punter, the tall, dark, and dazzlingly handsome young graduate student at Columbia on whom she models Tea Cake, Hurston describes it as an “obsession,” a love that wounds and must be escaped. “Everywhere I set my feet down,” she admitted as she describes her flight to Jamaica, “there were tracks of blood. Blood from the very middle of my heart. … I tried to embalm all the tenderness of my passion for him in ‘Their Eyes were Watching God.’”7 Where African American clubwomen in the pre–Harlem Renaissance era had represented themselves as “supermoral” missionaries, deploying a politics of respectability in which, as religious scholar Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham has put it, “they represented their sexuality through its absence—through silence, secrecy, and invisibility,” Hurston finds strength in a kind of shameless candor, a refusal either to carry the burden of respectability or to be shamed by those who do. She borrows this approach from the blues.8

To speak of Hurston’s erotic life and to note the way she highlights that theme in her writings is in no way to discount her achievements as a cultural investigator and author. She was fearless, tireless, resourceful, and as resolutely independent of men as she was willing to engage deeply with them; she roamed the American South, including its northern migrant and Caribbean basin extensions, in pursuit of insight and material. But the sex in her texts, as African American literature scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. notes in his essay “Why Richard Wright Hated Zora Neale Hurston” (2013), was something that got Hurston in trouble with her black male peers. “The politics of sexuality remained deeply problematic within black literary circles,” writes Gates of the late 1930s, and he argues that the “heated, vitriolic exchange” between Wright and Hurston after the publication of Their Eyes was caused by “Hurston’s creation of a black female protagonist who was comfortable with and celebrated her own sensuality, and who insisted on her right to choose her own lovers in spite of the strictures of the black community.”9 In a 1937 review in the Communist Party’s New Masses, Wright had indicted Hurston’s novel for “facile sensuality” and argued that she was trying to titillate white readers (i.e., men) “whose chauvinistic tastes she knows how to satisfy.” Wright quotes, and Gates highlights, a by-now widely celebrated passage in which Hurston depicts the sexual awakening of her young black female protagonist, Janie Crawford, an awakening that is also a moment of spiritual enlargement:

She was stretched on her back beneath the pear tree soaking in the altochant of the visiting bees, the gold of the sun and the panting breath of the breeze when the inaudible voice of it all came to her. She saw a dust-bearing bee sink into the sanctum of a bloom; the thousand sister-calyxes arch to meet the love embrace and the ecstatic shiver of the tree from root to tiniest branch creaming in every blossom and frothing with delight. So this was a marriage! She had been summoned to behold a revelation. Then Janie felt a pain remorseless sweet that left her limp and languid.10

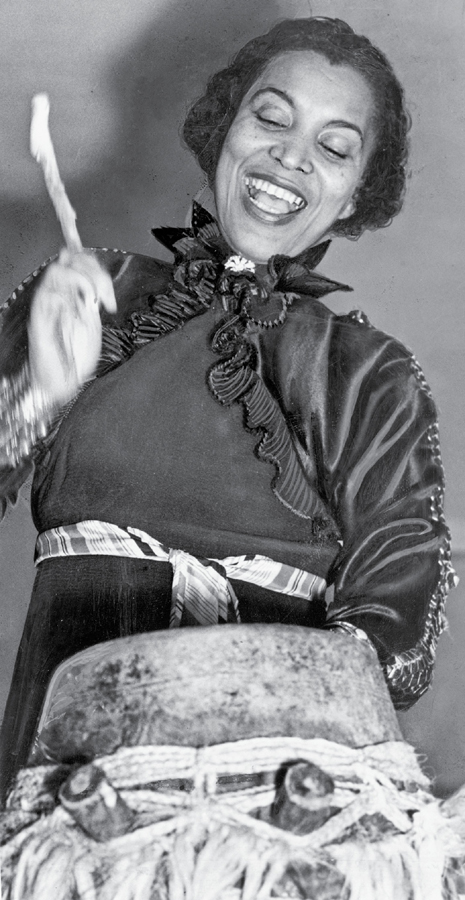

Zora Neale Hurston, 1937

(Library of Congress via Wikimedia)

“This is, I believe,” Gates writes, “the first orgasm depicted in the entire history of African-American literature.”11 It is also, as I’ll show later in this chapter, a textual moment that aligns Hurston with the blues tradition in several important ways. Neither of those things was apparent to Wright; he just knew that he was dealing with an author—a troublesome woman—who, in his view, substituted sex for social engagement, which is to say that she spent too much time exploring black pleasures and not enough time indicting the southern white man as an inflictor of black pain. This charge was a half-truth, but not the whole truth, and Hurston responded by trashing Wright’s Uncle Tom’s Children (1935) for the opposite sin, heartlessness and violence driven by a masculine hunger for racial revenge. It was, she wrote, “a book about hatreds,” made up of “stories so grim that the Dismal Swamp of race hatred must be where they live. … There is lavish killing here, perhaps enough to satisfy all male black readers.”12

In our own time, of course, Hurston has become canonical, a “voice of the folk,” albeit one who complicates that project in ways that critics have begun to appreciate. Her erotic boldness now seems as tame as Bessie Smith singing, “Need a little sugar in my bowl.” We are finally able to pause, neither scandalized nor inclined toward heroine-worship, and do our best to see Hurston clearly. Where did she come from, and how did those origins, that background, shape her approach to the blues?

LIES, SECRETS, AND SELF-MAKING

Zora Neale Hurston’s entire life is founded on a lie—or, rather, a constructive bit of storytelling, a fantasy embraced and worked to her advantage. She was born in 1891 in Notasulga, Alabama, but in 1917, aged twenty-six and living on her own in Baltimore, she informed local school officials that she was sixteen years old, born in 1901, so that she could qualify for the free schooling that her unsettled and peripatetic life had prevented her from acquiring to that point. Her teachers and classmates bought the story. The scrubbed-off decade was a secret that she kept for the rest of her life: from friends, lovers, readers. Her first biographer, Robert Hemenway, gives her birth year as 1901 and her birthplace as Eatonville, Florida; Alice Walker, who tracked down Hurston’s gravesite and erected a memorial in 1973, had that wrong year engraved on the stone. In Dust Tracks, Hurston cites Eatonville—again, wrongly—as her birthplace but never gives her birth year. Scholar Cheryl Wall finally discovered Hurston’s true age with the help of census records.

Why did Hurston lie about her age and birthplace, and sustain the lie throughout her life? Valerie Boyd, author of a second biography, Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston (2003), thinks that the mystery lies in an abortive, possibly abusive relationship with a man that Hurston may have endured in 1914 or 1915: the lowest point in a life in a life filled with many ups and downs. She never wrote explicitly of what happened. But she did describe in Dust Tracks a series of prophetic visions that she had had as a girl, and one of them, Boyd suggests, holds the key: a vision of a “shot-gun built house that needed a new coat of white paint, [and] held torture for me, but I must go. I saw deep love betrayed, but I must feel and know it.”13 At a key moment in Dust Tracks, just before changing her age and returning to school, Hurston refers to this vision—the house “that had threatened me with so much suffering that I used to sit up in bed sodden with agony”—as having “passed,” which Boyd translates as the events themselves having actually come to pass. It’s clear,” writes Boyd, “that Zora suffered horribly during this buried time, so much so that she would never speak directly about her anguish or its causes.”14 Boyd takes this obscure and traumatic chapter of Hurston’s life as a kind of skeleton key, one whose shaping power is revealed by the act of will required not merely to survive and escape it but also to live a remarkably full, empowered, and productive life in its aftermath.

What does not destroy me makes me stronger: that was Nietzsche’s proclamation in Twilight of the Gods, but it is also the blues ethos in action. If we accept Boyd’s claim about this black hole, so to speak, in Hurston’s life story—a common-law relationship in her mid-twenties with a man who betrayed her love and physically abused her—then her decision to deny that part of her past after wrenching free from it, dialing back her age and reconfiguring her social identity in a way that enabled a fresh start and future triumphs, might strike us as an extraordinarily bluesy gesture. Yet her behavior stands notably at odds with the blues impulse, as Ralph Ellison describes it in his famous essay on Richard Wright’s Black Boy (1945), “an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one’s aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism.”15 Hurston didn’t finger the jagged grain of that particular disaster, at least not in her autobiographical writings. She squeezed it down to nothing, then buried it—the diamond, in a sense, that powered what followed. Appreciating this survival strategy helps us read the famous opening of her most famous novel with fresh eyes. “Women,” she wrote in Their Eyes, “forget all those things they don’t want to remember, and remember everything they don’t want to forget. The dream is the truth. Then they act and do things accordingly” (TE, 1). Hurston’s age—and her hometown, and her life—was hers to seize, reshape to her own needs, and work as she saw fit. Blues singers sing what could be true and what feels true, not the literal truth. Hurston embraces this concept with a vengeance, and gives it a gendered edge.

Hurston’s determined resilience is sourced in her unusual upbringing. Notasulga, in eastern Alabama near the Tuskegee Institute, was her residence for scarcely a year, and she never referred to it, never cared about it, after being carried out of it as an infant. Home was the “pure Negro town” of Eatonville, today a small incorporated township (and still 90 percent black) within greater Orlando.16 Her father, John Hurston, a preacher and carpenter, came upon the town by accident during one of his rambling journeys abroad, right around the time Zora was being delivered. A year later he sent for his wife, Lucy Potts Hurston, and the couple’s five children. Hurston’s parents were from somewhat different positions on the class spectrum of black southern life. John was an “across-the-creek Negro,” as the saying went; he was from the wrong side of the tracks. His people worked on white plantations. Lucy’s family was better off, more prideful. They were independent landowners, unhappy with their youngest daughter’s choice of husband. But John Hurston was immensely ambitious, Lucy Potts was eager to support those ambitions, and Eatonville provided John, and soon Zora, with an unusually hospitable field of action. Within a couple of years, John had built an impressive homestead and become the minister of a church in Sanford, twenty miles away. He was a gifted, charismatic orator, sexually compelling to his female parishioners, and this eventually created problems within the marriage. Hurston was never particularly close to her father—she thought that he just didn’t understand her—but her mother encouraged Zora to “jump at de sun,” to pursue her own ambitions, and this encouragement stuck.

More important even than the family constellation was Eatonville itself. As a town founded, inhabited, and run by African Americans, it was a rarity in the early modern South: a place where segregation held no sway and first-class citizenship was each resident’s birthright. In The Souls of Black Folk (1903), published during Hurston’s childhood, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote about what he called the “double-consciousness” that burdened black Americans, “this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others,” meaning whites.17 Hurston’s childhood in Eatonville, lived almost entirely out of sight of southern whites and their appraising, oppressive gazes, left her blissfully free from such double-consciousness. This is not to say that the specter of white violence was entirely absent. In the late 1930s, hired as a researcher by the Florida Writers Project, Hurston wrote “The Ocoee Riot,” a stark historical essay about a 1920 lynching and racial purge that had taken place in Ocoee, a mostly white town thirteen miles from Eatonville, roughly a decade after she had moved away.18 Zora personally confronted Jim Crow as a teenager when, after her mother’s premature death, she was sent to boarding school in Jacksonville. “Jacksonville made me know that I was a little colored girl,” she wrote, invoking the material and attitudinal signposts of southern segregation. “Things were all about the town to point this out to me. Streetcars and stores and then talk I heard around the school.”19 But this moral letdown came later, after Hurston’s basic psychological orientation, her sense of racial wholeness in the safety of an all-black idyll, had been established.

Like Handy and Hughes, both of whom ended up in New York City in the 1920s, Hurston was a part of the Great Migration, an epic movement of black southerners up and out of their restricted southern “place” and into the uncertain freedom of a northern urban Promised Land. Like the other two, but even more so, Hurston’s relatively privileged upbringing vis-à-vis the imprisoning, humiliating strictures of Jim Crow meant that, as a member of the black intelligentsia, she had little desire to shed her black southern cultural roots, including the blues, in an effort to rid herself of the stigma of having grown up down home. Quite the reverse: as a freshly minted member of the Harlem Renaissance, she played up her southern accent and locutions, remaking herself as a teller of tales and singer of folksongs at Harlem rent-parties and soirees. She did this even as she was writing and publishing her first stories—“Spunk” took second place in a 1925 competition sponsored by Opportunity, a journal of Negro life—and enrolling at Columbia University to study anthropology with Franz Boas. Boas was her most significant intellectual influence, a German-born cultural relativist whose approach was an antiracist rebuke to a long-standing tradition of scientific racism by which “peoples” (i.e., races) and their cultures were organized in a hierarchy of biological, cultural, and moral advancement, with whites (Nordics, Caucasians) at the top, blacks (Hottentots, pygmies) at the bottom, and others (Malays) somewhere in the middle. Boas said to Hurston, in effect, “My European academic culture isn’t higher or lower than the folk culture that you imbibed as a girl in Eatonville, and that folk culture certainly isn’t ‘primitive.’ Each culture is an equally valuable and evolved response to the social circumstances of the people who deploy it.” By licensing Hurston to envision the intimate world of Eatonville—the porch of Joe Clarke’s store where the men had told stories, played cards, bragged, swapped “lies”—as culture, Boas prompted an epiphany in Zora. Her lifelong campaign to explore, document, understand, explain, and body forth the power and brilliance of black southern folklore begins here.

THE NEGRO FURTHEST DOWN

Blues song was merely one cultural element, albeit an important one, in the archive that she sought to explore. With help from Boas, who rounded up several small research fellowships on her behalf, Hurston left New York early in 1927 on what turned out to be a six-month maiden voyage: the southern migrant returns home with the “spyglass of anthropology” as her guide, looking to collect material in Eatonville and beyond. Brimming with confidence but suspended awkwardly between the conflicting imperatives of a (former) native participant and university-trained investigator, Hurston failed to fill her trawling nets. “I knew where the material was all right,” she confessed later, gently mocking her own cluelessness. “But, I went about asking, in carefully accented Barnardese, ‘Pardon me, but do you know any folk-tales or folk-songs?’ The men and women who had whole treasuries of material just seeping through their pores looked at me and shook their heads. No, they had never heard of anything like that around there. Maybe it was over in the next county. Why didn’t I try over there? I did, and got the selfsame answer” (DT, 175).

Although the trip was, in her view, a failure as a folklore collecting expedition, it paid unexpected dividends when Hurston ran into Langston Hughes in Mobile, Alabama. Hughes had been on his own tour of the South—Memphis, Baton Rouge, New Orleans—after being invited to read his blues poetry at Fisk University’s graduation in Nashville the previous month. The two friends ate fried fish and watermelon, then headed north in Hurston’s beat-up car, according to biographer Boyd, pausing frequently “to pick up folk songs and tall tales, to meet guitar players and conjure doctors, to visit small-town jooks and country churches.”20 They ended up in Macon, where they attended a concert by Bessie Smith, overnighted at a local hotel, and woke in the morning to hear her voice: she was staying down the hall, it turned out, and “practice[ing] … with gusto.” The blues writers lingered to chat with the Empress of the Blues, who delivered a memorable chestnut: “The trouble with white folks singing the blues is that they can’t get low down enough.”21

In December 1927, Hurston headed south out of New York on a second and much more consequential expedition. This time she was subsidized by Charlotte Osgood Mason, a wealthy white patron—“Godmother,” as she insisted her beneficiaries call her—who was also assisting Hughes, poet Claude McKay, painter Aaron Douglas, and other of Harlem’s young black creatives. Mason would provide substantial cash subsidies; Hurston would do the fieldwork, bring her news of “the negro furthest down,” and, importantly, hand over her findings at the end, for publication in Mason’s name. It was a devil’s bargain of sorts, one that Hurston struggled to navigate for the next half-dozen years. Ever the survivor, Hurston bought a new car, packed a pistol, and hit the road. The voyage, which she dramatized in Mules and Men and reprised in Dust Tracks on a Road, led once again to Eatonville, where blues guitarist Bubber Mimms and his fellow front-porch layabouts urged Hurston on toward Polk County, forty miles southwest. Familiar with “Polk County Blues,” incited by their tales of the strong, salty women who haunted the region’s backwoods jooks, Hurston headed south for “corn (likker) and song.”22 And it was there, in the town of Loughman, that Hurston moved into the living quarters of the Everglades Cypress Lumber Company and spent the next four-and-a-half months immersing herself in the rough, boisterous, blues-filled culture of Florida’s inland frontier.

Rough means rough. Hurston’s autobiographical writings make much of the fact that she was a tomboy, unafraid to use her fists; she writes of savagely beating her stepmother when tensions between them reached a boiling point and confesses that she and Punter slapped each other around at a similar moment of aggrieved high feeling. But Hurston, for all her feistiness, was a minister’s daughter and child of privilege compared with the men and women of the lumber camp. Much of the drama in her encounter with the camp’s denizens emerges from the class difference that frames their interactions. She registers this difference in a range of ways: in their colorful vernacular language (“yo’ entrimmins” for “your name” [MAM, 63]), in their suspicion of her new car (they think she’s a revenue agent; she convinces them that she’s a bootlegger), and in the way the men are intimidated by her “$12.74 dress from Macy’s” (MAM, 63) that she had on “among all the $1.98 mail-order dresses” (MAM, 63) worn by the camp’s women. “I did look different,” she admits, “and resolved to fix all that no later than the next morning” (MAM, 63). She is, she realizes very quickly, a high-class woman—or somebody being seen as one—trying to connect with a low-down crowd. She connects through music: convincing Jim Presley, one of the camp’s leading musicians, to back her up on guitar as she sings “John Henry.” It’s a ballad, not a blues, but this moment of musical teamwork has precisely the effect she yearns for, dissolving class differences and embedding her within the folk community:

So he played and I started to sing the verses I knew. They put me on the table and everybody urged me to spread my jenk [Have a good time], so I did the best I could. Joe Willard knew two verses and sang them. Eugene Oliver knew one; Big Sweet knew one. And how James Presley can make his box cry out the accompaniment!

By the time that the song was over, before Joe Willard lifted me down from the table I knew that I was in the inner circle. I had first to convince the “job” that I was not an enemy in the person of the law; and, second, I had to prove that I was their kind. “John Henry” got me over my second hurdle.

After that my car was everybody’s car. James Presley, Slim and I teamed up and we had to do “John Henry” wherever we appeared. We soon had a reputation that way. We went to Mulberry, Pierce and Lakeland. (MAM, 65)

This passage offers us a vivid illustration not just of the way Hurston leverages her own modest musical talents—she was an enthusiastic but mediocre singer—to connect with a folk community and enable her folklore-collection mission, but also of the blithe cluelessness with which she cozies up to the local men, never thinking about how this might make other women in the camp feel. To say that her car became everybody’s car is to say that she had suddenly become Queen Bee, a focus of masculine attentions. The women, it turns out, are furious at the interloper who is making music with, traveling with, and presumably sleeping with, their boyfriends. They have knives in hand that they are itching to use on Hurston—a powerful way of making their feelings known to her and the community.

What a bluesy situation! And what an extraordinary opportunity for a cultural investigator, to be drawn this deeply into the seething passions of the people you’re trying to understand. Hurston’s guide in all this, her native informant par excellence, is Big Sweet: a big, strong, fierce, trash-talking mama bear who vividly clarifies the dangers that await her naive guardian as the two women play cards in the Pine Mill jook, the rollicking, blues-music-filled social center of the logging camp. The most pressing problem is a rival of Big Sweet’s named Lucy and her side-girl, Ella Wall:

“Dat li’l narrer contracted piece uh meatskin gointer make me stomp her right now!” Big Sweet exploded. “De two-face heifer! Been hanging’ ’round me so she kin tote news to Ella. If she don’t look out she’ll have on her last clean dress befo’ de crack of day.”

“Ah’m surprised at Lucy,” I agreed. “Ah thought you all were de best of friends.”

“She mad ’cause Ah dared her to jump you. She don’t lak Slim always playing JOHN HENRY for you. She would have done cut you to death if Ah hadn’t of took and told her.”

“Ah can see she doesn’t like it, but—”

“Neb’ mind ’bout ole Lucy. She know Ah backs yo’ fallin’. She know if she scratch yo’ skin Ah’ll kill her so dead till she can’t fall. They’ll have to push her over.” (MAM, 149)

In Seems Like Murder Here, I wrote at length about Hurston’s unsettling encounter with the violent folkways of the Pine Mill jook. I framed it both biographically—a tough girl herself, Hurston wasn’t this tough, and knew it—and with reference to the blues tradition as a whole, where “cutting and shooting” and the braggadocio associated with those two forms of interpersonal violence were routinely confronted by Deep South blues performers who worked the juke joints.23 Indeed, countless blues recordings make lyric capital out of the sort of mayhem Big Sweet and Lucy are threatening here. “Don’t you bother my baby,” Muddy Waters sings of his female lover in “Gone to Main Street” (1952), “no tellin’ what she’ll do / She might cut you, she might shoot you too.” In this respect, the violence that Hurston confronts at the Pine Mill testifies to the fact that she has encountered the Real, in sociocultural terms: seriously low-down blues people, this at the very moment when Broadway and Tin Pan Alley, as both she and Hughes knew well, were being flooded with emotive white damsels and various sorts of pop-lyrical confections to which the word “blues” had been dubiously appended.

Yet when we take into account Valerie Boyd’s claim about the anguish that a twenty-something Hurston had suffered a dozen years earlier during her “buried” time in the shotgun house, at the mercy (or so Boyd believes) of a lover who physically abused her until she managed to break free, then another perspective on this juke joint immersion experience suggests itself. I believe that Hurston found Big Sweet, Lucy, and their hyperviolent threats so compelling because they offer her living models of feminine indomitability: women who could not possibly have allowed themselves to be manhandled and forced into the sort of soul-killing subordination that Hurston herself apparently was, if only briefly. They may be fighting over men, but they don’t depend on men to do their fighting for them. They are figures of power: black southern badwomen who take shit from nobody, and certainly not from men, including white men. (When the white quarters-boss, trying to keep order on a particularly raucous evening, demands that Big Sweet give him her knife, she shouts, “Naw suh! Nobody gets mah knife,” and “Don’t you touch me, white folks!,” an act of resistance that thrills the juke joint crowd. “You wuz a whole women and half uh man,” pronounces Joe Willard after he leaves. “You made dat cracker stand off a you.” (MAM, 152). Hurston saw in Big Sweet a version of the woman she might have been—or might have been saved by—at that vulnerable earlier moment in her life.

Willie King playing for dancers at Betty’s Place in Prairie Point, Alabama

(courtesy of the photographer, Bill Steber)

Hurston’s vivid rendering of the Pine Mill is animated not just by this sort of threatened mayhem, deadly serious one moment and playful the next, but also by her attention to the way blues music provides the soundtrack to after-hours carousing once these lumber workers get off work. “The jook was in full play when we walked in,” she writes, evoking the scene of communal performance. “The piano was throbbing like a stringed drum and the couples slow-dragging about the floor were urging the player on to new lows. ‘Jook, Johnnie, Ah know you kin spank dat ole pe-anner.’ ‘Jook it Johnnie!’ ‘Throw it in de alley!’” (MAM, 143). Even this brief passage is chock-full of cultural insight, from the way a percussive approach shapes the pianist’s barrelhouse dance aesthetic—keeping the African drum alive in America’s portion of the Global South—to the call-and-response urgings from multiple audience members and the way those urgings reinforce both the drum-song element and “get down” aesthetics, another African cultural bequest. Lowering or dipping the body is, in West Africa, a way of connecting with the earth and deepening spiritual intent; to “throw it in de alley” and explore “new lows,” in musical terms, is to dig down into the nitty-gritty, play for real, testify from the soul, but also, in this New World context, to get nasty, incite sexual heat, facilitate the mating dance of the slow-dragging couples.24 Hurston gets all this into her thick description. Like Handy and Hughes, she also finds a place for the familiar AAB blues stanza, rendering melismatic sung vernacular as written text in a way that foreshadows the violence that is about to explode through the jook:

Heard the new singing man climbing up on

Tell me, tell me where de blood red river ru-u-un

Oh tell me where de blood red river run

From mah back door, straight to de risin’ sun.

Heard Slim’s bass strings under the singing throbbing all Africa and Jim Presley’s melody crying like repentance as four or five couples took the floor. Doing the slow drag, doing the scronch. Joe Willard doing a traveling buck and wing towards where I stood against the wall facing the open door. (MAM, 178)

This passage comes just before Lucy heads toward Hurston with an open switchblade in hand, precipitating a free-for-all brawl. Before discussing that moment, it’s worth pausing to note a fascinating element of her participant-observer fieldwork that Hurston leaves out of Mules and Men: the fact that she introduced these lumber camp laborers to the poetry of Langston Hughes.

“I read from ‘Fine Clothes’ to the group at Loughman,” she wrote to Hughes in March 1928, “and they got the point and enjoyed it immensely.”25 They understood and enjoyed Hughes’s blues poems, surely, because the formal, attitudinal, and imagistic elements that he employed—AAB repetitions, a preoccupation with troubled male-female relationships, and a brooding focus on sex and violence, especially knives—were everyday currency in the Pine Mill, as was the vernacular voice in which he wrote. Hurston left Fine Clothes to the Jew out of her narrative because including it would have undercut her portrait of a preliterate backwoods folk community, but she was so astonished by the response that, according to biographer Boyd, she started reading Hughes’s poetry everywhere she went—railroad camps, phosphate mines, turpentine stills—during the remainder of her trip. “They call it ‘De Party Book,’” she wrote to Hughes in July in during an extended stay in Magazine, Alabama. “They adore ‘Saturday Night’ and ‘Evil Woman,’ ‘Bad Man,’ ‘Gypsy Man.’ They sing the poems right off, and [on] July 1, two men came over with guitars and sang the whole book. Everybody joined in. It was the strangest and most thrilling thing. They played it well too. You’d be surprised. One man was giving the words out—lining them out as the preacher does a hymn and the others would take it up and sing. It was glorious!”26

This remarkable passage shows us that the process through which she and Hughes used blues song as raw material, transforming oral performance into literary text, could be reversed by the black folk community, so that blues literature itself became the raw material for a collective vernacular performance. This picture of a warm and convivial celebration is complicated, however, by the contents of the four “adore[d]” poems mentioned by Hurston, which together sketch the sort of violent and profane good-timing world that led black southern church people to condemn the blues as the devil’s music. “I ain’t gonna mistreat ma / Good gal any more,” begins “Evil Woman, “I’m just gonna kill her / Next time she makes me sore.” “Bad Man” is narrated in the voice of a similarly ill-tempered lover, one filled with “meanness” and “likker” who beats his wife and his “side gal too.”27

Black southern blues culture was a thrilling scene of discovery for Hurston, one that offered her a wealth of folkloric material and encounters with memorable individuals, but it was also a culture pervaded by interpersonal violence: brags, threats, and hands-on retribution. Women were men’s equals in this last regard; Hurston found this gender equity compelling—and humorous, at least at first. “Negro women are punished in these parts for killing men,” she joked shortly after arriving in Loughman, “but only if they exceed the quota” (MAM, 60). But she also found the violence chilling when she realized that she, too, had been drawn into the charmed circle: a woman marked for death by a vengeful, knife-wielding rival. When Big Sweet advises Hurston that she should be prepared to run for her life if Lucy or Ella comes after her, the participant-observer suddenly bears witness to her own fear: “I thought of all I had to live for and turned cold at the thought of dying in a violent manner in a sordid sawmill camp” (MAM, 151). A week later, Lucy makes a play for her that Big Sweet disables, upping the ante. “I shivered,” writes Hurston, “at the thought of dying with a knife in my back, or having my face mutilated” (MAM, 154).

All of this leads inexorably, as Hurston tells it, to a final showdown at the Pine Mill jook. Hurston’s panicked response, as she sees Lucy heading toward her with knife in hand, is a stunning reversal of the generally comic tone with which she has narrated her immersive experience in the lumber camp’s social world. “I didn’t move but I was running in my skin. I could hear the blade already crying in my flesh. I was sick and weak” (MAM, 179). Then Big Sweet leaps once again to her defense and Jim Presley punches Hurston violently, protectively, hurling her toward the door and shouting, “Run you chile! Run and ride!”:

Slim stuck out the guitar to keep two struggling men from blocking my way. Lucy was screaming. Crip had hold of Big Sweet’s clothes in the back and Joe was slugging him loose. Curses, oaths, cries and the whole place was in motion. Blood was on the floor. I fell out of the door over a man lying on the steps, who either fell himself trying to run or got knocked down. I don’t know. I was in the car in a second and in high just too quick. Jim and Slim helped me throw my bags into the car and I saw the sun rising as I approached Crescent City. (MAM, 179)

The guitar, which has been instrumental in opening this blues community to Hurston and her cultural investigations, has been transformed into a weapon that opens a path to escape. Hurston’s tone is flat and affectless, her narrative kinetic and open-eyed; she offers us a stunned epiphany, it would seem, as four-and-a-half months of participant-observation end in an adrenalized rush. When Hurston narrates this same episode in Dust Tracks, seeking perhaps to entertain a white audience, she plays up the weaponry angle in a way that veers toward coon-song cliché: “Switch-blades, ice-picks and old-fashioned razors were out. One or two razors had already been bent back and thrown across the room, but our fight was the main attraction” (DT, 190–91). But the gist of the story, in both cases, is the same: forcibly exiled by the blues-filled black folk community that she has sought to understand, inadvertently inciting a murderous rage in a local woman, Hurston flees the jook to save her own life.

Why is this, of all things, the story that Hurston chooses to tell about her encounter with the blues and blues people? I’ve already suggested several possible answers, including her desire as a cultural anthropologist to find and honor the Real—a self-contained backwoods locale, intense passions, authentic blues—at a moment when Broadway and Tin Pan Alley were diluting, trivializing, and profiting from the music. Hurston also shapes her representations, as I’ve noted, in a way that highlights the fearsome power of women: a feminist point, surely, and one that perhaps addresses a deep psychological need evoked by Boyd, but a point that is also undercut by the way she represents herself as foolishly naive and ultimately disempowered within the world of the Pine Mill jook. The best answer to the question, it turns out, is Their Eyes Were Watching God, a novel written not long after the publication of Mules and Men.

A PAIN REMORSELESS SWEET

One of the most important prewar blues novels, along with Claude McKay’s Home to Harlem (1928) and Gilmore Millen’s Sweet Man (1930), Their Eyes is Hurston’s attempt to rewrite her Florida backwoods blues immersion experience in a way that wins her a victory in the juke joint rather than allowing her be driven into exile. She accomplishes this through a surrogate, Janie Crawford, and specifically through Janie’s midlife romance with Tea Cake, a younger bluesman who embodies the paradoxes of blues culture as Hurston had come to know them. Tea Cake has many virtues as a lover; he ministers to Janie in ways that deepen and intensify her emotions, heal her from wounds engendered by previous husbands, connect her with a black folk community, and help her claim her fullness as a self-possessed subject. But he, like the blues culture he emblematizes, has a violence problem. He is a juke joint fighter, adept with razor and gun, and he brags about his willingness to use violence on others—an aspect of his character that Janie initially disavows but is ultimately forced to confront. Tea Cake doesn’t merely resemble Big Sweet in this regard: Hurston literally puts Big Sweet’s words in Tea Cake’s mouth, a verbatim transfer of threatened mayhem from the folklore study to the novel. She also has Tea Cake do for Janie precisely the thing that Big Sweet won’t do for Hurston: instruct her in the arts of violence. Big Sweet pooh-poohs the idea of teaching Hurston how to handle a knife; “You can’t do dis kind uh fightin’,” she insists (MAM, 175). But Tea Cake—Hurston’s creation—is delighted to teach Janie how to handle a gun. “Oh,” he said, “you needs tuh learn how” (124). As it turns out, Janie will use the skills Tea Cake has taught her to kill him in self-defense late in the novel, thereby preserving her own life and symbolically purging the novel of the violence he embodies. Yet even as she kills off Tea Cake, she keeps his memory alive in the final scene, a moment of “singing and sobbing” (183) that evokes a kinder, gentler blues. Here, I argue, Hurston works a complicated spell and achieves a retroactive triumph over the spirited but volatile blues community at Loughman that had driven her from its doors.

Their Eyes is an exemplary blues novel, and not just because it features a Florida bluesman—he plays piano and guitar—as a key protagonist. As several critics have noted, Janie’s three marriages together constitute an AAB blues verse: the first two are similarly unfulfilling (both men care more for material things than for her), the second is worse than the first (the reiteration + intensification of the A-prime line), and the third is a triumphant answer to the problem posed by the doubled romantic disaster (the B line as a response to the call of the repeated A line).28 The novel also illustrates Angela Y. Davis’s influential claim in Blues Legacies and Black Feminism (1997) that the themes of travel and sexuality were so prevalent in early blues because the freedom to travel and the freedom to choose one’s lover(s) were two crucial things that distinguished African Americans in the postslavery years from their slave-born parents and grandparents, who’d been chained to the plantation and, in the matter of intimate relations, subject to the whims of the master.29 Janie Crawford’s life is marked not just by multiple husbands of her own choosing and, with the third husband, a large helping of sexual satisfaction, but by several consequential journeys in pursuit of love, including a trip with Tea Cake down onto “de muck”—rich farmland adjacent to Lake Okeechobee—that enables her to forge an immersive connection with a blues-playing, blues-using community. Finally, both the plot and imagistic patterning of Their Eyes can be glossed with uncanny precision by one specific blues recording, “Bumble Bee,” a hit for Memphis Minnie in 1929:

Bumble bee, bumble bee, where you been so long

Bumble bee, bumble bee, where you been so long.

You stung me this morning, I been restless all day long.

I met my bumble bee this morning as he flying in the door.

I met my bumble bee this morning as he flying in the door

And the way he stung me, he made me cry for more

Hmmmmm, don’t stay so long from me

Hmmmmm, don’t stay so long from me

You is my bumble bee, you got something that I really need.

I’m gonna build me a bungalow, just for me and my bumble bee.

I’m gonna build me a bungalow, just for me and my bumble bee.

Then I won’t worry, I will have all the honey I need.

It’s likely, although not provable, that Hurston knew of “Bumble Bee” or one of the four follow-up versions released between 1929 and 1931, including this recording, “Bumble Bee #2”; she had a lot to say about race records—not always kind things, to be sure—and she had a particular interest in raunchy vernacular song, the culture of “the man in the gutter,” as she termed it.30 This song is relatively tame by those standards but still provocative in the way it configures sexual intercourse as a mixture of sex and violence, a “sting” administered by a lover who is imaged as a bumble bee. In the first three stanzas, it evokes the singer’s desire as something that is intensified by her lover’s absence, and this element turns out to be a crucial part of the interpretive framework that the song extends toward the novel. (The wayward, stinger-bearing bumble bee is a perfect symbolic rendering of Davis’s travel-and-sexuality thesis.)

If we think back to the scene of Janie’s sexual awakening under a pear tree, we might remember that it is precipitated by a “dust-bearing bee sink[ing] into the sanctum of a bloom”—which is to say, by a generative symbolic sting, a sexual union of bee and blossom—and that the orgasm it precipitates in Janie fills her with “a pain remorseless sweet.” The relevance of Memphis Minnie’s song should be obvious here. Pain and pleasure, apparent opposites, are yoked to create yet another example of the blues dialectic: in this case, a sexual sting that awakens Janie into desire and, in Minnie’s words, makes her cry for more. The novel images that cry as her response to a newly sensed lack that begs to be filled by an as-yet unidentified lover. “Where were the singing bees for her?” wonders Janie, gazing longingly at the world after her orgasmic reverie. “Nothing on the place nor in her grandma’s house answered her” (TE, 11).

Unfolding according to the logic encoded in this bluesy scene, Their Eyes Were Watching God takes the form of a quest-romance designed to win Janie a man who will sting her thrillingly—ravish her, fill her with sweet remorseless pain, bring her to sexual completion surcharged with romantic passion—in a way that fulfills the promise made by the bees under the pear tree. The novel gains power from the way Hurston frames Janie’s erotic journey with reference to the markedly different experience of Nanny, the slave-born grandmother who has raised her. Both Nanny and her daughter Leafy, Hurston’s absent mother, were raped—by a white slave owner in Nanny’s case, a black schoolteacher in Leafy’s—and gave birth out of wedlock. Nanny sees sexuality, especially among the unwed, as a dangerous thing, a source of heartbreak and unfreedom, and doesn’t want to Janie to become a “spit cup” used by men (19). Janie, freeborn, sees sexual fulfillment as her birthright, a component of the ideal marriage into which the pear tree and buzzing bees have initiated her. Grandmother and granddaughter come into conflict; Nanny slaps Janie across the face, then hugs her; Janie bursts into tears. (We notice, if we’re paying attention, that the novel has, with that back-and-forth exchange, engaged the pain-and-pleasure dialectic of the blues.) Nanny dies shortly after convincing Janie to marry Logan Killicks, a property-owning but sexually unattractive black farmer.

In the novel’s blues schema, Killicks is the establishing complaint of the initial A-line. During a postslavery era when black southern folk are trying to figure out what it means to live a free and self-possessed life, Killicks, with his sixty acres and a mule, looks like a great catch to Nanny—but of course Nanny isn’t Janie, and to Janie, who doesn’t love him, doesn’t enjoy looking at him, and feels exploited by him like a kind of mule-woman for her labor power, he’s “desecrating” the pear-tree vision that serves as her soul’s North Star. So she abandons him within a year. In so doing, she rejects Nanny’s slavery-era vision of what freedom should look and feel like for a young black woman in the early years of the new century. It just doesn’t fit her.

Janie leaves Killicks for Joe “Jody” Starks, who will soon become her second husband.31 He wanders into view as her first marriage is on its final legs: a “cityfied, stylish dressed man” (26) whistling as he strolls along the road that fronts the farm. Smooth-talking and self-confident, he chats her up and confesses his desire to be a “big voice” (27) in a community that will allow him to realize his ambition. He engages her deep hunger to journey the world—the travel imperative Davis identifies as a key blues theme—even as she assesses him skeptically in line with her pear-tree hunger to be sexually stung in a thrilling way. “Janie pulled back a long time because he did not represent sun-up and pollen and blooming trees, but he spoke for the far horizon” (28). After wooing her for a week while Killicks is off in the fields, he wins her hand and carries her away toward a future that will, she is now convinced, fulfill her vision of romantic completion. “From now on until death,” she tells herself as she leaves her old life behind, “she was going to have flower dust, and springtime sprinkled over everything. A bee for her bloom” (31).

In the novel’s blues schema, Starks is the A-prime line: the problem repeated, with emphasis. The disaster he represents takes a while to become apparent. Driven by overweening ambition, Joe transports Janie to a brand-new all-black town of Eatonville—Hurston models him on her own father—and becomes the mayor and proprietor of the general store, where he installs Janie as checkout clerk and figurehead. He’s entrepreneurial; he takes the town over, helps build it. But he also begins to play out a second vision of post-Emancipation black freedom: not Killicks’s forty-acres-and-a-mule vision of independent yeoman farmers, but a recapitulation of slavery, of white mastery. Joe builds a “gloaty, sparkly white” house (44). He has spittoons, and spits in them. He bosses his fellow black townspeople around in such a way that they complain about the “bow-down” sound of his voice (44). Hurston is attentive to the supreme irony: here, at a postslavery moment in an all-black town, Joe’s vision of freedom is a recapitulation of the slavemaster’s prerogatives. With the help of his “big voice,” he wants to be boss over every living thing, including Janie. He wants his wife to sit in the “high chair” like a queen, separated from the townspeople the way he is, but he also wants her to submit to his every command and accept his periodic belittling silently, without protest. When his belittling becomes violent—he slaps Janie around one night until her ears ring when she accidentally scorches the dinner she’s cooked for him—she watches her dream of a bee for her bloom disintegrate. “She wasn’t petal-open anymore with him,” Hurston tells us. “She had no more blossomy openings dusting pollen over her man” (67–68).

If Boyd’s claim about Hurston’s painful lost time under a lover’s violent thumb in the shotgun house is correct, then Hurston’s portrait of Joe Starks as a suffocating oppressor revisits that primal scene: the novelist digs down into her own crushing disillusionment to find a buried strength within Janie that will be the grounds for future action. “She had an inside and an outside now,” Hurston tells us after Janie recovers from the beating, “and suddenly she knew how not to mix them” (68). Keeping her own counsel, Janie holds return fire until the day when Joe and a handful of locals are standing around the store; prompted by one man’s comment about the way she has cut a plug of tobacco, Joe mocks her incompetence with a knife and then insults her middle-aged woman’s body. That knife is important: Hurston has put into Joe’s mouth essentially the same critique that Big Sweet made of Hurston: “You don’t know how tuh handle it” (MAM, 176). But the public humiliation superadded by Joe distinguishes his comment utterly from the big-sisterly protectiveness of Hurston’s juke-house friend, and in that moment, Janie suddenly finds her own voice—a voice that echoes Big Sweet’s aggressive woofing. “You big-bellies round here and put out a lot of brag,” she tells Joe, “but ’tain’t nothin’ to it but yo’ big voice. Humph! Talkin’ ’bout me looking’ old! When you pull down yo’ britches, you look lak de change uh life” (75).

In one stunning moment, signifying mercilessly on Joe’s shriveled penis, Janie executes a death blow to her husband’s vanity. Furiously resentful, he dies within a few pages, at the end of the following chapter. And then, after a brief but important interregnum in which Janie dwells in the lonesomeness of an empty house, sounds her own soul, finds it fit, and takes joy in the “freedom feeling” (86) that has come over her, Tea Cake enters the picture.

BLUES MADE AND USED

In the novel’s blues schema, Tea Cake is the answering B-line: the response to the doubled disaster that has been Janie’s marital life to this point. In almost every respect he is the antithesis of Logan and Joe. They were older than Janie; Tea Cake is younger. They demanded that she work; he invites her to play (checkers, late-night fishing, back-and-forth banter). They were men of means, focused on the future and determined to accumulate property; he’s a man of no means, a musician and lover focused on the here and now. They seemed incapable of taking pleasure in her beauty and telling her so (or at least Joe devolved to this condition as the marriage proceeded); Tea Cake takes pleasure in her beauty, tells her so, and holds up a mirror, insisting that she do the same. Tea Cake stimulates, challenges, liberates, and heals Janie, and the blues that he lives and plays are an intrinsic part of this, although they also introduce complications. One way he steals her heart, for example, is by playing out the logic of “Bumble Bee #2”: summoning up sexual passion and then absenting himself from the scene in a way that leaves her restless all day long. Where Joe, with his big voice, was omnipresent in a way that Janie found suffocating, Tea Cake stays away for a full week after their initial encounter, giving her a chance to miss him. He brings his guitar—“mah box” (96)—when he returns; the following night he sits down at her piano and begins to play and sing the blues. An adjunct to his playful flirtations, the music becomes the soundtrack to their blossoming romance. He leaves suddenly that second night, after the subject of the twelve-year age difference has come up, and his masterly deployment of call-and-response aesthetics—insisting that he has to “struggle aginst” (101) his feelings for her, then parrying her skepticism—awakens her passion. Her feelings, echoing the restless sexual hunger evoked in “Bumble Bee,” promise the fulfillment of her youthful initiation under the pear tree:

All next day in the house and store she thought resisting thoughts about Tea Cake. She even ridiculed him in her mind and was a little ashamed of the association. But every hour or two the battle had to be fought all over again. She couldn’t make him look just like any other man to her. He looked like the love thoughts of women. He could be a bee to a blossom—a pear tree blossom in the spring. (101)

Even as Tea Cake plays Janie in every sense of the word, Hurston makes clear that his skills, such as they are, derive from the low-down, blues-filled world in which he spends his time. “Bet he’s hanging ’round some jook or ’nother,” Janie sneers the first time he absents himself. “Glad Ah treated him cold. Whut do Ah want wid some trashy nigger out de streets? Bet he’s livin’ wid some woman or ’nother and takin’ me for uh fool” (102). The morning after they make love for the first time, Janie wakes to feel Tea Cake “almost kissing her breath away” (103), and that line is a near-verbatim quote from Bessie Smith’s “Empty Bed Blues” (1928), where a “new man” thrills the singer “night and day,” leading her to proclaim, “He’s got a new way of lovin’ almost takes my breath away.”

As the romance between Tea Cake and Janie develops, it becomes clear that she is deepening as a subject under his been-here-and-gone ministrations: becoming at once more feelingful and more edgy, filled with strong and contradictory passions yoked together in a familiar blues dialectic:

In the cool of the afternoon [after they first made love] the fiend from hell specially sent to lovers arrived at Janie’s ear. Doubt. All the fears that circumstance could provide and the heart feel attacked her on every side. This was a new sensation for her, but no less excruciating. If only Tea Cake would make her certain! He did not return that night nor the next and so she plunged into the abyss and descended to the ninth darkness where light has never been.

But the fourth day after he came in the afternoon driving a battered car. Jumped out like a deer and made the gesture of tying it to a post on the store porch. Ready with his grin! She adored him and hated him at the same time. How could he make her suffer so and then come grinning like that with that darling way he had? (103)

Certainty and doubt, love and hate, pain and pleasure: rarely has a work of American literature offered a more pointed object lesson in the emotional lineaments of blues romance. Hurston wants Janie to get thoroughly bluesed up: pulled out of the “classed-off” high chair in which Nanny and Joe wanted to keep her and down onto the rich, fragrant muck of open-hearted, fully embodied life. But Hurston also wants us to attend to a related educational process through which Janie’s eyes are opened to the violence of Tea Cake’s world, a violence that is an intrinsic part of who he is.

Tea Cake, like Big Sweet, is a skilled knife-fighter. He takes as much pleasure in those abilities as he takes in his facility as a gambler, lover, and blues musician. An attentive reader will notice Hurston hinting slyly at this element of his makeup in one of the earliest descriptions she offers of him—as seen through Janie’s eyes, significantly, although Janie doesn’t recognize the import of what she sees: “She looked him over and got little thrills from every one of his good points. Those full, lazy eyes with the lashes curling sharply away like drawn scimitars” (92). The question of Tea Cake’s violence is first raised overtly when Hezekiah, who helps Janie in the store, warns her against dating such a low-class man. “Is he bad ’bout toting pistols and knives tuh hurt people wid?” she asks, pushing back. “Dey don’t say he ever cut nobody or shot nobody neither” (98), Hezekiah concedes. But Hezekiah is wrong. And Janie, who watches her lover buy a new switch-blade knife and two decks of playing cards before he heads out alone on a juke joint expedition, is wrong when she insists to herself, anxiously, “Tea Cake wouldn’t harm a fly” (120). When he falls back through the front door at daylight, he has been cut in several places and lost some blood; $300 richer, he regales her with a story about how he beat up the man who accused him of cheating at dice. “Baby,” he brags, “Ah run mah other arm in mah coat-sleeve and grabbed dat nigger by his necktie befo’ he could bat his eye and then Ah wuz all over ’im jus’ lak gravy over rice. He lost his razor tryin’ tuh git loose from me. He wuz hollerin’ for me tuh turn him loose, but baby, Ah turnt him every way but loose” (121).

Big Sweet’s phrase, bragging about her readiness for a knife fight with Ella Wall, was “Ah’ll be all over her jus’ lak gravy over rice.” Hurston changes the tense and gender, then puts those words in Tea Cake’s mouth. Her boisterous working-class hero isn’t just a playful bluesman-lover but also a skilled and enthusiastic brawler. As she paints iodine on his wounds and cries, Janie is burdened by this new knowledge; he has, in fact, been “hanging ’round some juke or ’nother,” but she’s in too deep for sneering now. And the “self-crushing love” she feels for him, a love that leads her soul to “[crawl] out from its hiding place” (122), suggests that she is spiritually enlarged by the relationship, regardless of its problematics.

Blues culture, as Hurston had experienced in at the Pine Mill and as she dramatizes it in the person of Tea Cake, was animated by a powerful expressive need that sometimes spoke through violence. In black working-class social spaces like the jook, brags and boasts were backed by deadly force, as were romantic claims. Hurston “shivered” in the lumber camp when she began to understand the risk to her own person. But she also found herself intoxicated by the energy, joy, and creative spirit that surged within the camp’s juke house. Their Eyes conjures with this paradox in pointed ways as the love affair between Janie and Tea Cake plays out. Tea Cake liberates Janie, for example, by teaching her how to shoot “pistol and shot gun and rifle” (125). She thrives under his tutelage, becoming a better shot than he is. This subplot, in symbolic terms, shows the violence of the jook being put to constructive use. Tea Cake disciples Janie more deeply into the blues by taking her down on “de muck,” an agricultural district in the Everglades bordering Lake Okeechobee where migrants and fieldwork are plentiful and where the music thrives as well. “All night now the jooks clanged and clamored. Pianos living three lifetimes in one. Blues made and used right on the spot. Dancing, fighting, singing, crying, laughing, winning and losing love every hour. Work all day for money, fight all night for love. The rich black earth clinging to bodies and biting the skin like ants” (125).

Janie’s spiritual liberation requires that the imprisoning dream of class ascent that Nanny inculcated in her and Joe Starks did his best to impose on her be extinguished. Allowing herself to be romanced by Tea Cake began the process; accompanying him onto the muck and choosing to work in the fields with the migrant community’s other women continues it. The room she and Tea Cake share in the “quarters” is transformed into a veritable juke joint, filled every night with trash-talking gamblers, storytellers, and an audience for Tea Cake’s box-picking. Janie has left the big white house and its high chair far behind; blues culture, the all-black space and sociality of the jook, has wholly supplanted the spiritually retrograde vision shared by Nanny and Joe, a white inheritance at odds with the truth of black being.

As an egalitarian space in which labor and play fuse under the sign of blues, the muck is also an Id-space in which the “lower” human passions flower fully and can thus be experienced and explored. Here, too, Tea Cake disciples Janie by misbehaving in the way that bluesmen do—letting his erotic attentions wander toward a “little chunky girl” (130) named Nunkie. Nunkie attracts his interest in the fields, importantly, by hitting him “playfully,” mingling sexual enticements and low-level violence. “Janie learned what it felt like to be jealous,” Hurston writes. “She never thought at all. She just acted on feelings” (131). Seized by a “cold rage” (131) when she discovers them together, Janie angrily confronts Tea Cake; later, back at the quarters, she hits him, chasing him from room to room and hurling accusations. She’s seething, fully activated, wildly alive—and sexually receptive, even voracious:

They wrestled on until they were doped with their own fumes and emanations; till their clothes had been torn away; till he hurled her to the floor and held her there melting her resistance with the heat of his body, doing things with their bodies to express the inexpressible; kissed her until she arched her body to meet him and they fell asleep in sweet exhaustion. (132)

Here is the sexual completion that Janie has been seeking ever since the pear-tree revelation, when she saw a “dust-bearing bee sink into the sanctum of a bloom; the thousand sister-calyxes arch to meet the love embrace.” This passage is the fulfillment of that prophecy. The “sweet exhaustion” she shares with Tea Cake echoes the “pain remorseless sweet that left her limp and languid” in that earlier moment. So this is a marriage. Hurston wants us to know that. A deep, primal, and fulfilling connection has been established.

And yet, and yet. The endgame of Their Eyes is a complicated exercise in which the violence that Tea Cake carries—a violence associated with the jook, an enlivening, passion-deepening, and even life-sustaining violence in certain contexts—is also revealed for what Hurston herself knew it to be: a mortal danger to be evaded. The word “also” is crucial here. Hurston’s vision is capacious, multivariate; Tea Cake’s descent into violent jealousy and madness is governed by a both/and logic, not an either/or logic. At bottom, however, is a wound inflicted on one black bluesman’s soul by an ideology of whiteness that seems to have infected the world in which he lives. When a thin-lipped, light-skinned woman named Mrs. Turner praises Janie for her “coffee-and-cream complexion” (134) and badmouths Tea Cake for being dark, Tea Cake later whips Janie to relieve “that awful fear inside him” and to “[reassure] himself in possession” (140). Racism, rendering him insecure about his masculine prerogatives, accentuates a preexisting condition—a jealous possessiveness and willingness to use violence as its guarantor that the jook has bred in him. Later, after Tea Cake and Janie have barely survived a hurricane and Tea Cake, struggling to protect Janie, has been bitten by a mad dog that is “nothin’ all over but pure hate” (158), the bluesman is forcibly impressed into service by a pair of white men with guns seeking black laborers to bury the dead. Tea Cake bridles and later escapes to the Everglades with Janie, complaining broodingly about how the town he just left was “full uh trouble and compellment” (163). The novel, which has effectively banished white people for most of its length, succumbs to whiteness, or at least acknowledges whiteness’s dispiriting presence, in these late pages. Tea Cake’s own violence has always subsisted in uneasy relation with the “compellments,” the disciplinary prerogatives, of Jim Crow. Now the bluesman becomes the novel’s version of a Jesus figure: not a blameless innocent but still a good man and husband who is forced to suffer for the sins of this particular southern world. In a final paroxysm of violent, rabies-induced jealousy, Tea Cake pulls a pistol out from under his bed and shoots—or shoots at—Janie. She kills him with a shotgun blast, knowing even as she does that “Tea Cake was gone. Something else was looking out of his face” (172). He has, we are to understand, finally been driven mad by the virus of white supremacy that has corroded his being. But that virus has acted in a way that simultaneously licenses, and exaggerates, his knife-fighter’s predilection for hands-on violence.

It is easy to miss the subtlety with which Hurston interleaves the forces that ultimately destabilize Tea Cake and require Janie to kill him. The brilliance of Their Eyes Were Watching God is that it finds a way of encoding this complexity even while offering us a moving love story, a blues story with a tragic ending that is also redemptive and even liberating. In killing Tea Cake, the novel kills off the violent mayhem spawned by his juke joint world, even while conferring on Janie the ability to defend herself with righteous violence. In the glorious love affair between the bluesman and Janie, of course, the novel insists that the passions conveyed by the blues are a great and noble thing. They deepen and transform lives. They save a good woman, helping her escape from containment and despair.