bar 10

The Blues Revival and the Black Arts Movement

“Look like ah, what the Klan couldn’t kill, look like we gonna let die for lack of love. Look like now we don’t, we don’t much listen to ourselves, you know what I mean. We don’t really listen to ourselves any more, Mister Can’t Sing Blues Black Man, be telling me the blues is ’bout submission, shuffling, and stuff too ugly to hang on yonder wall. But submission is silence, submission is silence, and silence is NOT my song!”

Kalamu ya Salaam, “My Story, My Song” (1990)

OUR STORY, OUR SONG

A central theme of this book is that we, as a variegated contemporary global community of people with musical and literary investments in the blues, are dwelling, whether we’re conscious of it or not, in the aftermath of significant historical and cultural developments. We’re the survivors, and inheritors, of things that happened decades, and centuries, ago. The long shadow of New World slavery hovers darkly, indisputably, over our project. In her influential theoretical-autobiographical meditation, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016), African American literature scholar Christina Sharpe insists that “transatlantic slavery was and is the disaster. The disaster of Black subjection was and is planned; terror is disaster and ‘terror has a history’ … and it is deeply atemporal.” Her intention, she says, is to do “wake work”: to explore “the afterlives of slavery” as they manifest in literary texts and in the daily lives of black people. “Living in the wake,” she explains, “means living the history and present of terror, from slavery to the present, as the ground of our everyday Black existence.”1 Sharpe’s haunted vision of our contemporary moment, a Faulknerian vision in which what is supposedly past refuses to remain there but instead suffuses and suffocates the present, is part of a so-called Afro-pessimist movement within black diasporic circles. It is a blues vision shorn of comedy—much closer to Wright’s than Ellison’s—and it resonates with the ghastly fall from grace marked by President Obama’s eight years in office: from the dream of beloved community evoked by the black First Family’s triumphant election-night appearance on Chicago’s Grant Park stage before a huge multiracial crowd in November 2008 through a now-familiar litany of dead young black men whose killings, beginning with Trayvon Martin in February 2012, sparked the emergence of Black Lives Matter and mass public protest.

It is no coincidence that the reemergence of black bluesism, a conscious, principled, and angry reclamation of the blues as black culture, takes place during that period. The phrase “a new black consciousness” may feel slightly dated today, evoking as it does a specific moment in the mid-1960s, but that sort of awakening, evoked by the word “woke,” is what we are witnessing—not just in American society at large and in academic circles, but anywhere the blues is/are at issue. The keynote panel at the 2019 International Blues Challenge was titled “The Blues and Race”; moderated by Dr. Noelle Trent of the National Civil Rights Museum, its participants included performers Bobby Rush, Teeny Tucker, and Marquise Knox, representing three generations of prideful black blues claimants.2 Younger black writers, including Derrick Harriell, Tyehimba Jess, Kiese Laymon, Zandria Robinson, and Kevin Young, are laying claim to the blues with directness and urgency as well. In her essay “Listening for the Country” (2016), sociologist Robinson, a Memphis native, listens deeply into the curated collection of blues CDs in her father’s old truck a decade after his death, tantalized by the traces of personal and familial grief interleaved with racism and black precarity that she hears there:

Daddy had a blues all his life that I couldn’t begin to know, though I had so desperately tried to understand it as his first-born and accomplice. … I put on my ethnographer hat and went back to the CDs [I had burned for him] that I had found in the truck. …

Daddy had given me a list of requests for Bobby “Blue” Bland. … When I first saw the list, I thought it was mighty narcissistic of Daddy to be having the blues with all he had done to Mama. But listening to that music in the wake of Daddy’s death some ten years later, I was compelled to consider for the first time the shape of Daddy’s hurt—and his right to it. He had hurt Mama and the rest of us, but I had not given him space to hurt, not about anything, really, beyond a stubbed toe. His upbringing in Jim Crow Mississippi with disappearances and violences and the concomitant beatings from Big Mama Rosie. A missed scholarship opportunity because a racist counselor hadn’t turned in a form. His visit to Memphis that was only supposed to be a stop on the way to St. Louis that turned out to be an entire life and abrupt death. His guilt about what he had done to Mama, or to us. His mama’s death, the only time I saw him cry, and all the other people he loved who had died or gone missing. Having to tell his daughter about the hole in her child’s father’s head. And those women who weren’t Mama. I wondered if Daddy was thinking of them when he listened to Bland sing. … Had they broken my daddy’s heart while he was breaking Mama’s? Did he hear Mama’s city pain in Bland’s declaration that he had a “hole where [his] heart used to be”? Or was he thinking of his own heart, and how he had turned Mama mean?3

This is wake work, in Sharpe’s terms, work that registers the disappearances and violences that were the ground of everyday black southern existence during that period, even as it evokes a complex of blues feelings accessed through a daughter’s intersubjective encounter with her father through the medium of blues recordings. “When you’re talking about the blues,” Jess recently told an interviewer, making a broader pitch for blues’ continuing utility to black writers, “you’re talking about the roots of African American literature, really the core of American literature. … That was the literature we had before we could read and write. And once we were allowed to read and write without the force of death being put upon us, all that imaging went right into the literature. And that’s the connection between African American literature and the blues. So there’s no separation between the two.”4 “When I think about blues,” Harriell agrees in words that align the music with Black Lives Matter, “I think about marginalized lives. I think about black lives. … I don’t need to go to a blues bar in the Delta to hear blues. I think that pain, that anguish, that legacy is in music right now.”5

Today’s new black consciousness, especially when it takes blues as its purview, has two important historical precedents. The first is the Harlem Renaissance, especially Hughes’s manifesto “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” with its invocation of “the bellowing voice of Bessie Smith singing Blues” as a “prod” with which to “penetrate the closed ears [of] colored near-intellectuals.” The second, which bears directly on our own moment and is a principal focus of this chapter, is the Black Arts Movement, a decade-long (1965–76) creative eruption that tends to be remembered not for its investments in blues but for a soundtrack anchored in jazz. Archie Shepp, Sun Ra, and Albert Ayler—jazz-revolutionist proponents of the “New Thing”—played downtown fundraisers and uptown marches for Amiri Baraka’s Black Arts Repertory Theatre School in the heady spring of 1965, joining the faculty as founding members. Black Arts poets embraced saxophonist John Coltrane as a secular saint after his death in 1967, modeling their spoken-word performances on his shrieking, onrushing, freedom-yearning style to create what literary critic Kimberly Benston has termed “the Coltrane poem.” Poet-shamans as diverse as David Henderson, Haki Madhubuti, Sonia Sanchez, Jayne Cortez, A. B. Spellman, and Michael Harper, made this sort of elegiac spoken-word praise-song into one of the movement’s signal innovations and enduring achievements.6

Yet blues, a politically problematic but equally vital expressive legacy, was also a crucial instrument of racial and cultural self-definition for a wide array of Black Arts writers and their academic fellow travelers, including Sanchez, Cortez, and Madhubuti, Amiri Baraka, Larry Neal, Ron Karenga, Stephen Henderson, Ben Caldwell, Eugene Redmond, Henry Dumas, Quincy Troupe, Al Young, Stanley Crouch, Nikki Giovanni, James Cone, Kalamu ya Salaam, Tom Dent, and a host of lesser-known writers published in Negro Digest and Black World and anthologies such as Black Fire (1968), The New Black Poetry (1969), and The Black Aesthetic (1971). To this list might be added writers and critics such as Toni Morrison, August Wilson, Sherley Anne Williams, Ishmael Reed, Sterling Plumpp, Alice Walker, Gayl Jones, Arthur Flowers, Angela Davis, Yusuf Komunyakaa, John Sinclair, Jon Michael Spencer, Harryette Mullen, Allison Joseph, Sharon Bridgforth, and the younger black writers I’ve just discussed: contemporaries and inheritors of the Black Arts Movement whose work significantly engages with blues forms, blues themes, and the black ancestral “Blues God” invoked by Larry Neal. Far from being the shortest and least successful movement in African American cultural history, as Henry Louis Gates Jr. has provocatively claimed, the decade-long Black Arts Movement has had a broad and enduring impact on African American literature.7 It has remade that literature as a blues-toned legacy—proudly invested in, and supremely conscious of, its own southern-born vernacular taproot, a survivor’s ethos of self-willed mobility, self-determined sexual personhood, and bittersweetly lyric self-inscription elaborated in the face of continuing legacies of black precarity and the spiritual and epistemological failures of whiteness.

To the extent, however, that the Black Arts Movement envisioned a splitting-off of black art from white America and a purification of that separate sphere, it has indeed proved to be a failure—at least with respect to contemporary blues culture. Although the so-called chitlin’ circuit of juke joints, clubs, and concert venues lingers on in the modern South, supplying a small but loyal black audience, the mainstream universe of festivals, nightclubs, bands, record labels, DJs, blues societies, websites, and internet discussion groups has grown in the past sixty years from a coterie audience of folk blues fans into a multimillion dollar, worldwide enterprise: predominantly white-administered and white-attended and, except for a modest admixture of black blues musicians on the bandstands, a palpably non–African American thing. Blues are white culture these days: a way a certain kind of earthy, hip, antiracist whiteness (and a certain kind of geeky, volunteerist, middle American whiteness) knows itself, and shares that knowledge with like-minded others.

The irreversible onslaught of white blues fandom and musicianship is a fact, one that some African American blues performers, indebted to such audiences for their livelihoods, have noted with a dismay that shadows the contemporary scene.8 In one branch of blues literature, too, the rising white tide is unmistakable. The 1990s witnessed a remarkable flowering of black blues autobiographies by Sammy Price, Mance Lipscomb, Willie Dixon, B. B. King, David Honeyboy Edwards, Ruth Brown, Yank Rachell, and Henry Townsend; the next decade and a half added the life stories of Etta James and Buddy Guy. In every case, black vernacular voices were shaped into print by white ghostwriters. The very existence of such autobiographies is partly a result of the folk-and-electric Blues Revival of the 1960s, which gave performers such as Lipscomb and King access to large new white audiences, and partly a result of the traditionalist tenor of the contemporary scene, which venerated Edwards (d. 2011) and King (d. 2015) and today venerates Guy and Bobby Rush as sources of badly needed Deep South authenticity within a strange new blues world made uneasy by its own whiteness.

This world, grounded in the drama of cross-racial connoisseurship, had already become visible to black intellectuals as a cultural crisis in the early 1960s, when Amiri Baraka, then LeRoi Jones, did his best to dynamite the rails. “Old bald-headed four-eyed ofays popping their fingers,” rages Clay, the wildly antagonized young black protagonist of Dutchman (1964), accusing white blues lovers—and by extension his slinky white seductress/antagonist Lula—of being utterly clueless about the inner life of black folk,

and don’t know yet what they’re doing. They say, “I love Bessie Smith.” And don’t even understand that Bessie Smith is saying, “Kiss my ass, kiss my black unruly ass.” Before love, suffering, desire, anything you can explain, she’s saying, and very plainly, “Kiss my black ass.” And if you don’t know that, it’s you that’s doing the kissing. … If Bessie Smith had killed some white people she wouldn’t have needed that music. She could have talked very straight and plain about the world. No metaphors.9

Lula, offended by Clay’s truth-telling, stabs him in the heart shortly after this outburst and, with the help of other white passengers, hustles his warm corpse off the subway car.

Where do things stand, decades later? “Pack your bags & head to Memphis! for the Blues Foundation’s BluesFirst,” proclaims the website for the nation’s premier blues advocacy organization:

The ONLY International Convention and Expo for Blues Societies, Fans, Musicians and Industry … Learn Important Strategies for Successful

Blues Retail

Publicity

Studio Recording

Budget Preparation

Newsletter Production

Blues Radio

Internet Marketing

Grant Writing

Blues in the Schools Programs

Plus a Special Information Panel by The BMA

Includes:

3 Days of Strategy-Packed Learning Opportunities to Make Your Blues Organization Succeed

3 Days of Fun, Friends and Blues Networking

A VIP Pass to All the Clubs on Beale Street for the International Blues Challenge Competition

Plus admission to:

Shake and Howdy Reception

The Keeping the Blues Alive Awards Brunch

Blues, Brews & BBQ Party

The International Blues Challenge Competition10

Bessie Smith would have to kill a whole lot of white people to make a dent in this particular blues world, and whether or not she “need[s] that music” has become a moot point: Marcia Ball, an older white Texas pianist and mainstay of the contemporary scene, is more than ready to cover the gig. Baraka’s Lula has become a blues diva, and Baraka’s Clay still doesn’t stand a chance against her.

BLACK POWER AND BLUES POWER

Ironies abound on the postmodern blues scene; one of the most poignant was evoked by Kalamu ya Salaam, Black Arts poet and historian, at the end of his pithy and provocative treatise “the blues aesthetic” (1994). “Why and when,” he laments, “did blues people stop liking the blues?”11 Salaam’s plaint about waning black interest in the quintessential black art form, one he had voiced four years earlier in a spoken word performance, “My Story, My Song,” from which this chapter’s epigraph is drawn, is not new. Although there are signs these days of a modest renaissance among younger black musicians and writers, the loss of the black blues audience remains the changing same of all blues commentary, white and black, during the past sixty years.12 In its white incarnation it led to the founding of Living Blues magazine (“A Journal of the Black American Blues Tradition”) by a group of white aficionados in 1970 and still animates white-run blues societies intent on “keeping the blues alive” by teaching “blues in the schools” to compliant black children. In its black version the complaint echoed through the pages of Ebony in the late 1950s and early ’60s in articles with titles such as “Are Negroes Ashamed of the Blues?”13 As the 1960s progressed and James Brown and Aretha Franklin became the rage, the complaint was picked up by black DJs and blues musicians such as B. B. King, who watched helplessly as the black youth audience for blues melted away. “On this particular night in this particular city,” King remembered later of a soul show he’d played during the period, “the audience booed me bad. I cried. Never had been booed before. Didn’t know what it felt like until the boos hit me in the face. Coming from my own people—especially coming from young people—made it worse.”14

If by “liking the blues” one means believing in the cultural value and political efficacy of the blues, then a significant number of Black Arts poets and theorists—the self-appointed intellectual vanguard of the blues people—stopped liking the blues around 1965, when LeRoi Jones broke faith with bohemian interracialism and took the A Train from Greenwich Village up to Harlem. The integrationist tenor of Mississippi’s Freedom Summer experiment the previous year, along with its Delta blues groundnote, were swept out as Black Power angrily swept in. Fanon’s dismissal of the blues in Towards the African Revolution (1967)—a “black slave lament … offered up for the admiration of the oppressors”—undergirded the Black Arts revaluation; the song-form was guilty by association with the now intolerable social conditions that had produced it.15 “The blues are invalid,” Maulana Ron Karenga declaimed in an influential essay in Negro Digest (1968), “for they teach resignation, in a word acceptance of reality—and we have come to change reality.”16 For Karenga, Madhubuti (Don’t Cry, Scream [1969]), Sanchez (“liberation / poem” [1970]), and others, blues were the embarrassing residue of an older generation’s helpless passivity, no longer useful in a time of revolutionary transformation and expressive license. “We ain’t blue, we are black,” insisted Madhubuti, deploying blues repetitions only to reject the stance of black dejection he construed them as signifying. “We ain’t blue, we are black. / (all the blues did was / make me cry).”17 “no mo / blue / trains running on this track,” agreed Sanchez. “They all be de / railed.”18 Soul and jazz were the sounds of the urban North: hip, inspiring freedom-songs. “Soul music is an expression of how we feel today,” black DJ Reggie Lavong at New York’s WWRL told Michael Haralambos in 1968, “blues was how we felt yesterday.”19 Blues could be the sounds of the urban North, and hip in their own fashion—white scholar Charles Keil helped clarify this in Urban Blues (1966)—but for an influential segment of Black Arts proponents, blues signified the benighted rural South: they were the cry of the slavery/sharecropping continuum, the sorrow-songs associated with what Baraka, in Blues People, had termed “the scene of the crime.”20

Yet for another, considerably larger cohort of Black Arts writers led by Larry Neal, the blues were something quite different: a cherished ancestral rootstock, an inalienably black cultural inheritance that could be put to political as well as aesthetic good use. “The blues,” countered Neal in “The Ethos of the Blues” (1972),

with all of their contradictions, represent, for better or worse, the essential vector of the Afro-American sensibility and identity. Birthing themselves sometime between the end of formal slavery and the turn of the century, the blues represent the ex-slave’s confrontation with a more secular evaluation of the world. They were shaped in the context of social and political oppression, but they do not, as Maulana Karenga said, collectively “teach resignation.” To hear the blues in this manner is to totally misunderstand the essential function of the blues, because the blues are basically defiant in their attitude toward life. They are about survival on the meanest, most gut level of human existence. They are, therefore, lyric responses to the facts of life.21

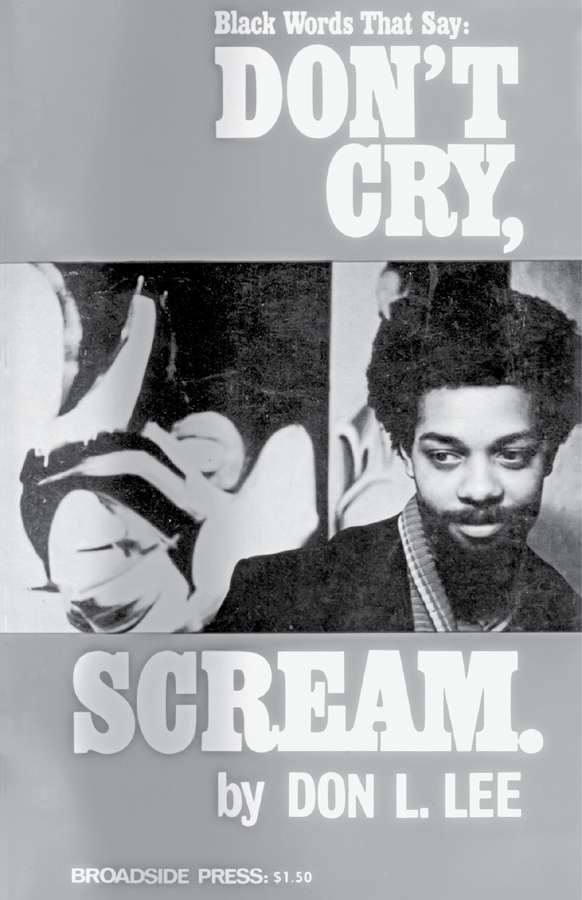

Album cover for Don’t Cry, Scream by Don L. Lee (Haki Madhubuti)

(courtesy of Archives & Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi)

These blues are not sorrow songs but survivor songs: the soundtrack of a spiritual warriorship that refuses to say die. These blues wrest far more than their share of swaggering lyric joy out of an evil world, inscribing personhood and sustaining the tribe in the process. “To write a blues song,” wrote Etheridge Knight in “Haiku” (1968), “is to regiment riots / and pluck gems from graves.”22 Such are the blues defended and celebrated by Neal (“For Our Women,” “Can You Dig It?”), Salaam (“The Blues (in two parts)”), Stanley Crouch (“The Big Feeling,” “Howlin’ Wolf: A Blues Lesson Book”), Jayne Cortez (“Lead,” “Dinah’s Back in Town,” “You Know”), James Cone (The Spirituals and the Blues), Al Young (“A Dance for Ma Rainey”), Stephen Henderson (“Blues, Soul, and Black Identity: The Forms of Things Unknown”), Quincy Troupe (“Impressions / of Chicago; for Howlin Wolf”), Eugene Redmond (“Double Clutch Lover”), Nikki Giovanni (“Poem for Aretha,” “Master Charge Blues”), Tom Dent (“For Walter Washington”), and Henry Dumas (“Keep the Faith Blues”), among others.23

“Blk people have done it to the english language,” insisted the southern-born Salaam in “The Blues (in two parts)” (1972), making his case for the aesthetic revolution wrought by those blue-toned survivor songs. “They have niggerized it. … We are finding that blk poetry has to do mostly with rhythm, images, & sound. … Most good images come from blues, blues singers were our 1st heavy poets.”24 “The blues,” proclaimed Crouch in “The Big Feeling” (1969),

is the most important art form ever produced in America, ever, possibly in the West. Because it has the “big feeling,” as John Lee Hooker says: It broke past the lie, became rudely vulgar in its exposition of truth, spit in the face of Venus de Milo (the armless bitch incapable of embrace), stumbled through the flung lye of loneliness, so often scalded walking barefoot in the glass-strewn alleys of anguish, maimed by memories, suffering the treason against the self which is called sentimentality, but, at the end with its tongue hanging out, in love: “Dun’t you want to rock?” Or, “Got a good rocking mama and the way she rock is all right!” That, is the final specificity of feeling and, of life: The woman reached, or wished for—“And say, babe, don’t you remember me?” That is, the Blues to me means: No one is crushed if he, or she, can summon the strength to understand what has happened, which is identity. Therefore, B. B. King need not be threatened by white musicians, he knows who he is and knows, as we all must: “As long as you’ve got Black People, you’ll have the blues.”25

Theomusicologist Cone, like Neal and Crouch, defended the blues in the name of black identity-formation; in The Spirituals and the Blues (1972) he had one eye on those white folklorists who claimed that the blues had no real protest content and another eye on Karenga, who argued the same point from a Marxist perspective. “The political significance of the blues,” wrote Cone, “is not very impressive to those who have not experienced black servitude. Neither is it impressive to persons who are fascinated by modern theories of political revolution. But for black people who live the blues, who experience and share that history with their black fathers and mothers, the blues are examples of Black Power and the courage to affirm black being.”26

Blues Power is Black Power! Both the white folklorists and the black revolutionists, Cone argues by implication, miss the liberationist moment in blues: the way, as he puts it elsewhere in his study, the “ritual and drama” of blues performance “preserve the worth of black humanity” and “affirm the somebodiness of black people” in the face of oppression. At once functional, collective, and committed, the blues foster a continuing revolution of black spirit, excavating and purging despair—rather than surrendering to it—on a daily basis.27

Some Black Arts writers, most notably Baraka, articulated a multivalent vision of the blues’ cultural and ideological function. Blues People (1963), Dutchman (1964), and “The Changing Same (R&B and New Black Music)” (1966) together sketch a capsule history of the evolving Black Arts attitude toward the blues: from a relatively benign index of “the Negro’s” changing attitudes toward America, to a register of political impotence and aestheticized black rage (“If Bessie Smith had killed some white people, she wouldn’t have needed that music”), to a rich, enduring, and endlessly inspiring black ancestral wellspring (“Blues (Lyric) its song quality is, it seems, the deepest expression of memory. … It is the racial memory”).28 Even Don L. Lee (Haki Madhubuti), who rejected the blues in Don’t Cry, Scream (1969) as an art that “exhibits illusions of manhood” and is “destroyed” by John Coltrane’s freedom-yearning ascension into “scream-eeeeeeeeeeeeee-ing,” could seemingly reverse his revaluation, celebrating Delta bluesman Son House in an untitled but closely observed praise poem published in 1970:

to himself he knew the answers

& the answers were amplified

by the sharpness of the broken bottle

that gave accent to the muddy music as it screamed

& scratched the unpure lines

of our many faces,

while our bodies jumped to the sounds of

mississippi.29

House, a Delta blues recording star in the 1930s and early ’40s, had been tracked down in the summer of 1964 by young white blues enthusiasts Nick Perls, Dick Waterman, Phil Spiro, and Nick Perls, who found House in Rochester, New York, after searching to no avail down in Mississippi. The trio put a guitar in House’s hands, coaxed him out of retirement, and worked the levers of white power to get him onto the bill at the Newport Folk Festival by summer’s end. With Waterman acting as his manager and booking agent, House played Carnegie Hall the following year, was featured in several documentaries, and enjoyed an entirely unexpected second act as a performer and recording artist.30 Without those efforts, paradoxically, House would have died in obscurity and Lee would never have had the occasion to observe him in action, or write the poem that resulted.

If white blues aficionados and black poets could, on occasion, be secret sharers of the music they loved and admired, then the polarized racial climate of the period tended to preclude overt acknowledgment of that common bond. Virtually all Black Arts writers, in fact, saw white enactments of and claims on the blues as an insult and a threat, one more invidious example of cultural theft rife with minstrelsy and false consciousness. “It should come as a surprise to no one,” critic Stephen Henderson told a black college audience in 1970,

that white people have tried to usurp the concept of “Soul” and to dilute its meaning. That is a function of their historical relationship to us, and that relationship has been parasitic, cannibalistic. … The history of our national music, i.e., so-called serious music, the history of popular music, the history of the American popular theatre, would be pallid indeed without the black energy and forms which were appropriated from us, and which we have foolishly called “contributions” to American culture. This is only now becoming clear, only now being publicly admitted. … The Janis Joplins of this world, and the Mike Bloomfields, and the Laura Nyros, and the Tom Jones’ are merely carrying on a time-honored tradition of swallowing the nigger whole. They are cultural cannibals. But how do you deal with the sickness?31

The sickness to which Henderson’s polemic refers is the Blues Revival, which by 1970 had shifted into high gear and by 1971 had been officially certified in Bob Groom’s slim monograph by that name.32 Henderson’s jeremiad, which was seconded in the writings of Don L. Lee, Ron Welburn, Calvin C. Hernton, and others, makes clear the degree to which the Black Arts Movement’s desire to reclaim and define the blues as a black cultural inheritance rather than a Negro “contribution” to American culture was being pressured by the truly daunting emergence of a mass white blues audience—an audience no less galvanized, it must be added, by established black performers such as B. B. King and Muddy Waters than by white insurgents such as Joplin and Bloomfield. The white culture industry seemed determined to overwhelm any Black Arts separation-and-purification scheme by capitalizing on white omnivorousness for the music, recasting black ancestral lines of descent in a way that seemed anathema to black aesthetic radicals. “Paul Butterfield worships Muddy Waters,” inveighed Ron Welburn in his essay on black music in The Black Aesthetic (1971),

who has never had so much money in his life. In fact, a black fathers/white sons syndrome is developing. A Chess label album cover pictures a black god giving the life-touch, a la Michelangelo, to a white neo-Greek hippie in shades. This is part of the Euro-American scheme. The black music impetus is only to be recognized as sire to the white world; a kind of wooden-Indian or buffalo-nickel wish. A vampirish situation indeed!

… African-Americans should continue to move as far away from this madness as humanly possible, spiritually, psychologically, and in the immediate physical sense at least. … Black music should not be allowed to become popular outside the black community, which means that the black community must support the music.33

Fathers and Sons (1969) was the title of a highly successful double LP that paired Muddy and Otis Spann with Butterfield, Bloomfield, Sam Lay, Donald “Duck” Dunn, and Buddy Miles: four black guys and three white guys, but also three fathers (Muddy, Spann, and Lay) and four sons, which is to say a thread of black ancestral connection in the person of Miles, a point obscured by the album’s iconographic cover art.

The “shoulds” and “musts” that mark Welburn’s jeremiad are a holding action in the face of a troubling and indisputable social fact: the young white audience for blues had swelled to fill a vacuum created by a vanishing young black audience. Even younger black intellectuals such as Henderson, enamored of the blues and angered at white borrowings, were forced to admit this. “About three years ago,” he chided a black college audience in 1970, “I wrote a short article in which I lamented the seeming indifference of young black people to what I call the most characteristic feature of black cultural life—the blues.”34 Like Welburn’s jeremiad, Henderson’s address at Southern University in New Orleans was an attempt to drum up black community support for an art form that suffered as many negative connotations within the race as it enjoyed positive (and profitable) ones out in the wider world. The black blues musicians themselves, as Welburn is too honest not to note, followed the money trail. “Until the mid-1950s,” observed Time magazine in 1971, “the music of Muddy [Waters] and his fellow bluesmen was marketed as ‘race music’ aimed almost exclusively at black communities. Today his new audience is largely young whites; Muddy now makes 20 to 30 college appearances a year, and he plays mostly in white clubs and theaters. For one thing, says Muddy, young whites are more responsive. ‘The blacks are more interested in the jumpy stuff. The whites want to hear me for what I am.’”35 “Yes, the blues is alive and well, all you people,” Hamilton Bims informed his Ebony readers in 1972, before cataloging the ways African American performers were oppressed by crime, class snobbishness, and shifting cultural politics within their own communities:

Indeed it is the subject of a worldwide craze. Blues performers are toasted in Europe and at open-air festivals from Monterey to Newport. …

Chicago bluesmen have had their crosses to bear. Many are respected, even idolized in Europe—yet the places that await them when they venture back home are often dungeons of violence and the paychecks are absurd. They have also been the victims of an intraracial snobbery—a legacy of the times when the blues was the property of contemptible old men hawking dimes on a street corner. Urbanized blacks have tended to deprecate the blues in favor, initially, of contemporary jazz and more recently that ethnic amalgam described as “soul.” The blues is often seen as an Uncle Tom expression, a cowardly admission of impotence and despair; while the “positive” projections of the James Brown school are viewed as infinitely more consistent with the current black mood.36

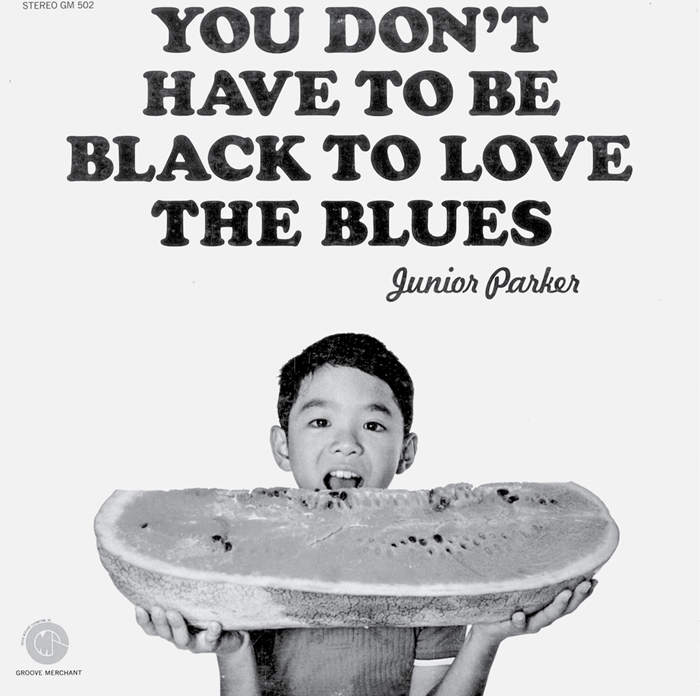

Even as Black Arts poetry readings and theatrical troupes were flowering in urban centers and on college campuses across the country during the late sixties, even as Crouch, Al Young, Tom Dent, and other young poets were crafting praise songs to blues performers such as Howling Wolf, Ma Rainey, and Walter “Wolfman” Washington, there remained a fundamental disconnect between the younger black generation and their blues-playing elders. Was this merely a black variation on the period theme, “Never trust anybody over thirty”? Yet the burgeoning white youth audience for blues not only trusted those elders, it venerated them in a way that most black kids—except that segment of the Black Arts vanguard—didn’t begin to. As late as 1969, after his remarkable success at the Fillmore West had certified his star status in the eyes of young whites, B. B. King could tell an interviewer, “I’ve never been asked to appear at a black college.”37 Junior Parker, according to cultural historian Michael Haralambos, hungered for but never achieved the sort of crossover success King, Waters, and Albert King had enjoyed; “the title of his last LP, ‘You Don’t Have To Be Black To Love The Blues,’ shows he was still trying to break through to that audience.”38 If the title of Parker’s 1974 album says little about Parker’s real designs on the mainstream market and much about his record label’s marketing strategy, then it makes painfully clear just what sort of pressures the Blues Revival was exerting on a black folk/popular form that Black Arts poets and theoreticians were intent on defining away from grasping whiteness and mainstream Americanness, away from capital-driven exoticism of the sort that Hernton lambasted in Black Fire: “Ray Charles, Mahalia Jackson, Lightning Hopkins, Little Richard—sex, soul, honkytonk!—it all represents something that will turn white folks on, something that will gratify their perversities.”39

To further complicate the cultural politics of the moment, 1969 marked the birth of the Ann Arbor Blues Festival: the first major blues festival held in North America, featuring Muddy Waters, B. B. King, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Junior Wells, Howlin’ Wolf, James Cotton, Otis Rush, T-Bone Walker, Luther Allison, Magic Sam and Son House. It also marked the emergence, in the festival’s program notes, of an ideology of self-conscious white blues universalism. The specter of “black rage,” evident on both college campuses and in the urban riots inventoried by the Kerner Commission Report (1968), had clearly roused the anxieties of white blues aficionados about the possible bad faith attendant on so thoroughgoing a white embrace of a black art so closely identified with the oppression of blacks by whites. White anxiety compensated by insisting on the black social provenance of the blues (no white folks at these origins!), even while elaborating a narrative of popular music’s “roots” in the blues and naturalizing the ascendance of contemporary white blues performers to a position alongside their black elders and peers. “Somewhere in this headlong rush of publicity and profit,” a certain Habel Husock informed Ann Arbor festivalgoers,

Album cover for You Don’t Have to Be Black to Love the Blues by Junior Parker

(image courtesy of Archives & Special Collections, J. D. Williams Library University of Mississippi)

contemporary music has stumbled on its roots in a joyous reunion. What that means is a full-fledged revival of the blues, the unique music of the American black man that has infused popular music with its echoes of Africa, slavery, and rural and urban poverty. …

The blues evolved in the secret culture of black America; a pure, ethnic form of self-expression. (Blues was neither invented by a Columbia recording engineer nor by the Cream). …

… The blues is alive and very well—it cannot be relegated to history for it continues to answer needs for man and has come to reach an audience much larger than a ghetto bar, a new audience which has recognized in itself the same passions and emotions that found their form in blues. The blues grows continually in the artistry of such men as James Cotton, Junior Wells and Buddy Guy. Many faithful white musicians refine the blues and mold the blues to suit the emotions of their backgrounds further, blues has been a launching pad for jazz riffs and improvisations.40

Husock is happy to grant Black Arts theoreticians their racial-ancestral claims—blues as “a pure ethnic form of self-expression” that evolved as “the secret culture of black America”—but only in order to clear a space for his universalist claims about “new audience[s]” outside the ghetto and “faithful white musicians” who “refine” and “mold” the blues. It was these latter sorts of sentiments, not merely antithetical to the ethnic-consolidationist project of the Black Arts Movement but an insult to black intelligence—was Janis Joplin really refining Big Mama Thornton’s blues?—that justifiably infuriated Henderson, Welburn, Hernton, and Lee. “Our music,” wrote Lee in 1970,

is being stolen each and every day and passed off as another’s creation—take Tom Jones and Janis Joplin, two white performers who try to sing black. They’ve not only become rich, while black musicians starve in their own creation, but those two whites, plus others—who are at best poor copies of what they consider black—will, after a short period of time become the standard. It will get to the point where when you speak of soul and black music, you will find people automatically thinking of white imitators.41

Whether or not Lee’s prophecy about white imitators has, in fact, come true in our own day is debatable. The white blues audience’s hunger for what the Europeans are fond of calling “real black blues” has, if anything, grown stronger in recent decades; Buddy Guy, Taj Mahal, and other headliners on the mainstream blues circuit command premium prices, and the European festivals (Burnley, Notodden, Blues Estafette) are notorious for preferring lesser-known black blues artists to rising white stars such as Kenny Wayne Shepard and Samantha Fish. At the same time, it is possible to find blues festivals advertised in the pages of major American blues publications such as Blues Blast and Blues Festival Guide in which six of the eight acts are all-white or contain a single black member, making white blues the acceptable de facto norm, if not exactly the standard.42 Often that token black member is a drummer or bassist, but not infrequently he is the Old School legend, the aging or elderly master—W. C. Clark, Henry Gray—backed up by willing white apprentices. Black fathers and white sons all over again, staging rituals of fellowship and reconciliation.

BLUES AIN’T NOTHING LIKE IT USE TO BE

Or are they symbolic transfers of cultural power in the service of profiteering white universalism? Once the fathers die, after all, the anointed sons take over; guitarist Bob Margolin makes a living these days on the basis of having played behind Muddy Waters in the early 1970s. The white blues audience today seems only too happy to embrace the actual children of deceased black blues legends—Shemekia Copeland, Bernard Allison, Big Bill Morganfield—as performers in their own right, and the last few years has seen the emergence of a new cohort of younger black male artists, both electric and acoustic, including Gary Clark Jr., Jerron “Blind Boy” Paxton, Marquise Knox, and Mr. Sipp, among others. But there was no way that Black Arts spokesmen could have anticipated these particular plot twists in the late 1960s. It was the white blues-kids, cultural interlopers and harbingers of the future, who bedeviled them. “For the 1970s and beyond,” insisted Welburn in “The Black Aesthetic Imperative,” “the success of political, economic, and educational thrusts by the black community will depend on both an aesthetic that black artists formulate and the extent to which we are able to control our culture, and specifically our music, from theft and exploitation by aliens.”43

At the height of the Blues Revival, black anxiety and annoyance at the displacement of black people from blues performance was an understandable response to a combination of factors: not just the swelling white audience and shrinking black audience for the music, not just the emergence of white blues stars such as Joplin and Butterfield but also the historical parallel offered by the rock ’n’ roll “cover” phenomenon of the 1950s (Pat Boone and Bill Haley profiting off the songs of Fats Domino and Big Joe Turner), and the rapidly evolving ideology driving the revival—a putatively antiracist, universalist ideology based on “feeling the blues,” an ideology that cleared space for white participation by either rejecting privileged black claims on the music or asserting them with a fervency that hoped to fend off black nationalist objections. In the former case the ideology might be summarized, “Now that we play the blues, we have made them our own”; in the latter case, “Now that we listen to your blues, we feel them as intensely as you do.”

Exhibit A in the former case was journalist Albert Goldman, author of a New York Times article headlined “Why Do Whites Sing Black?” that Henderson vigorously deconstructed before his college audience in 1970:

When he [Goldman] waxes ecstatic about Stevie Winwood, whom he calls “Super-Whitey No. 1,” who pretended that he was “Ray Charles crying in an illiterate voice out of the heart of darkness,” we see finally what it is all about. White people really understand black people and black culture better than black people, so why shouldn’t they get the credit. Thus Stevie Winwood, “Attaining a deeper shade of black than any dyed by Negro hands … became the Pied Piper of Soul.” And Paul Butterfield has created “a new idiom,” which is “half black and half white,” and has “done for the blues what no black lad could do—he has breathed into the ancient form a powerful whiff of contemporary life.” So there you have it. If that isn’t plain enough, Goldman ends his article with the following statement, which really shows the extent of his perversion.

Next Friday night at Madison Square Garden, Janis Joplin and Paul Butterfield will lock horns in what should be the greatest blues battle of recent years. The audience will be white, the musicians will be black and white, and the music will be black, white and blue, the colors of a new nation—the Woodstock Nation—that no longer carries its soul in its genes.

That is as plain as it has to be, for Goldman is sanctioning the use, the exploitation of black music for white nationalist purposes, without really owning that the music still belongs to us at all. And the technique of expropriation is plain—detach the music from its cultural context under the guise of liberalism and integration, then ZAP them niggers again.44

One may feel, as I do, that Paul Butterfield was a true innovator—one of the few white blues instrumentalists who extended the tradition rather than merely ventriloquizing his black influences—and at the same time share Henderson’s assessment of Goldman’s invidious fatuity here. That fatuity is a byproduct of Goldman’s hyperbolic style: he burlesques Winwood in the original article even as he celebrates him (“a fey pixie, who looks as if he was reared under a mushroom”), and he characterizes Joplin as “this generation’s campy little Mae West.”45 Yet Goldman, precisely by virtue of his tactlessness, asks all the right questions about the musical miscegenation that marked the heated late sixties moment at which the Black Arts Movement and the Blues Revival came to loggerheads:

Driven apart in every other area of national life by goads of hate and fear, black and white are attaining within the hot embrace of Soul music a harmony never dreamed of in earlier days. Yet one wonders if this identification is more than skin deep. What are the kids doing? Are they trying to pass? Are they color blind? Do they expect to attain a state of black grace? Let’s put it bluntly: how can a pampered, milk-faced, middle-class kid who has never had a hole in his shoe sing the blues that belong to some beat-up old black who lived his life in poverty and misery?46

Goldman shrewdly frames the Blues Revival in the context of racial polarization—a polarization abetted by (if not reducible to) the Black Arts Movement’s dedication to, as Larry Neal put it, “the destruction of the white thing, the destruction of white ideas, and white ways of looking at the world.”47 It seems entirely plausible, in fact, that the passion which drove white blues fans into the “hot embrace” of musical blackness as the sixties progressed was in fact an anxious response to the hot, angry rejection of white patronage, white solicitude, and interracial fraternity by a politicized blackness manifesting variously as Black Power, the Black Panthers, the Black Aesthetic, the Black Arts Movement, and Black Rage (1968). In the black blues recordings with which they established private rituals of communion, in the black blues artists who were delighted by (if sometimes also puzzled and unnerved by) their adulatory attentions at clubs and festivals, white blues fans during the Black Power years made a separate peace with blackness of a sort that ideologically driven public tensions (not to mention the Kerner Commission’s celebrated warning about the emergence of “two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal”) made almost impossible in any other civic setting. Blues Power, the title of albums by Albert King (1968) and Eric Clapton (1970), was, by this reading, a kind of anxiety formation against Black Power. The World of Blues Power! and Blues Power, Vol. 2, bestselling Decca compilations in 1969 and 1970, were anthologizing integrationist responses to the anthologizing separatist calls made by Black Fire (1968) and The Black Power Revolt (1968).

For all his trash-talk about “the white thing,” it was Black Fire’s coeditor Larry Neal, alone among his Black Arts peers, who was willing to entertain the idea that the Blues Revival’s white audiences might testify to the power and universal reach of black music. “Even though the blues were not addressed to white people and were not created by white artists,” he told Charles Rowell in 1974, “when white people heard the blues they knew it was a formidable music.”48 But of course the blues were being played, if not precisely created, by a sizeable cohort of white performers by the time the sixties drew to a close: what had begun at the Newport Folk Festival in 1963 as a charmed encounter between superannuated, somewhat exoticized black country bluesmen and an audience of white folkies had metastasized by 1968 into Eric Clapton and Cream transforming Robert Johnson’s “Cross Road Blues” into sheets of sound at the Winter Garden in San Francisco with the help of banked Marshall amps and hallucinogens. It had also morphed into Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child” version of the same New Thing. Musical miscegenation was a two-way street in the late sixties; Black Arts sensibilities betrayed considerable unease about what seemed like treacherously shifting blues ground, a postmodern hall of mirrors in which blue-eyed blues people were determining the idiom’s prevailing feeling-tone and those few younger blacks who had embraced the blues seemed to be losing contact with their essential blackness. James Thompson’s poem “Media Means,” published in Negro Digest in 1969, clearly signifies on the media-driven “scene” that embraced both Clapton and Hendrix:

… speaking

to Young Blacks

whom MEDIA has made

BELIEVE

that a Black Blues Chord

played by BLACKS

is an

ACID ROCK TUNE

that White imitation

of a very black feeling/

I was forced to scream:

INTEGRATION IS DREADFUL

when you don’t control

the media which makes

ZOMBIE/ISM a constant

condition.) IT SELLS IMAGES—

imitations of REAL

and REALITY imitates

IT:

Black folks imitating

white folks

who

imitate

THEM!49

“Blues done gone and got / Americanize,” complained poet Mae Jackson in a similar vein, also in Negro Digest (1969):

tellin’ me that I should

stay in school

get off the streets

and keep the summer cool

i says

blues ain’t nothing like it use to be

… and the folks singing it

ain’t singing for me

no more.50

Both of these poems sing the Blues Revival blues, voicing in the first-person “I” a collective black sense of outrage, enervation, and loss: loss of a familiar low-down blues-home safe from the encroachment of whiteness. Jackson’s vernacular voice reconstructs that home as a complaint against blues-singing white interlopers and their co-optive liberal platitudes—or, more precisely, against a comprehensive whiteness that manifests as both blues singing and platitude-mongering. “The Black Arts Movement,” Neal had famously declared a year earlier, “is radically opposed to any concept of the artist that alienates him from his community.”51 Means and Jackson embody this creed—their own black community orientation is evident—but the song they sing is a lament about their alienation from a brave new blues world that no longer speaks to or for them. Does their complaint sound familiar?

CANNIBALS AND BLUES GODS

For both the Blues Revival and the Black Arts Movement’s engagement with blues, 1970 was a watershed year, a transitional moment in which two very different social formations suddenly came into uneasy alignment. One index of this shift was Living Blues, a mimeographed newsletter featuring lengthy interviews with black blues musicians founded that year in Chicago by a group of seven young white journalists, oral historians, and proponents of French surrealism. What made the magazine unusual and controversial was an editorial policy that hewed to a black aesthetic critique of white blues later summarized by Paul Garon, one of the founders: “For those interested in the support and study of African-American culture, blues as purveyed by whites appears unauthentic and deeply impoverished; further, it too often represents an appropriation of black culture of a type sadly familiar. Finally, it can be economically crippling to black artists through loss of jobs and critical attention.”52 Each of these statements was a half-truth. The flailing, gravel-voiced, minstrelsy-tinged excesses of Janis Joplin could and did coexist with the preternaturally wise—and black-mentored—blues stylings of Bonnie Raitt, who took pains to acknowledge and share stages with her mentors; although middling rock-blues boogiemen such as Canned Heat and Alvin Lee may indeed have made more money than they deserved off of black-authored blues songs, black bluesmen such as B. B. King and Muddy Waters found the loss of the black youth market far more economically crippling than any such white appropriations, and were gratified by their sudden ascension into the mainstream. What was significant, in any case, was the emergence of black aesthetic radicalism among young white blues fans. Larry Neal’s call for the destruction of the white thing had drawn an unexpected response from his self-declared white allies.

Neal himself was hard at work on his black bluesist reclamation project: in the January 1970 issue of Negro Digest, he used his review of Phyl Garland’s The Sound of Soul to celebrate B. B. King’s achievement in terms that constituted an implicit rebuttal of Ron Karenga’s dismissal of the blues in the magazine’s pages two years earlier. “We are the continuation of Black memory,” Neal insisted,

our songs are the emanations of that memory; our rhythms the force that drives that memory.

Bessie Smith sang: that the meanest folks in the whole wide world lives on Black Mountain. She was singin’ ’bout niggers, evil and bad but surviving in spite of everything. Nigger/Black. Black music/niggers/the “nigger” in the music being its dominant force. …

But it is nigger energy that will rule. B. B. King has more to tell me about the world that I can use than most poets and intellectuals. Here he is talking to Phyl Garland:

“Blues is B. B. King. Yes, and I’ve been a crusader for it for 21 years. Without this, I don’t think I could live very long—not that I think I’m goin’ to live a long time anyway, but I don’t think I could live even that long if I had to stop playin’ or if I couldn’t be with the people I love so, the people that have helped me so much. … I couldn’t live! I try to give them a message. I try hard.”

How many of us are so dedicated to whatever it is that we do? How many of us commit ourselves so thoroughly to our work? How many of us link our work to the survival of both ourselves and our people?

… We will write our own scriptures. We will seek validation of the truths that we sense must exist in the holiest work of each one of us. From spirits like B. B. King, Jimmy Reed, Son House, James Brown, Smokey Robinson, Moms Mabley … an ethnic [sic] will be fashioned whose fundamental truths can be denied by no one. …

… New scriptures are in order. New mythologies. New constructs: Black Music as the Model for the Black Nation. …

We are a new species of Man, child. Liberation will come out of honky-tonk bars, gut-bucket blues, and the meanest niggers that have ever walked the planet. (Saw Bobby Blue Bland singing Uptown. He had on silver dashiki and his process.) The current Soul Music explosion illustrates the mass culture of Black America is still strong; and still dominated by the eternal spirit of the Blues God.53

According to Neal, not only don’t King’s blues teach resignation, as Karenga had insisted, but they powerfully respond to Karenga’s call for revolutionary black art: they are functional, collective, and committed—as committed as soul music, which the blues underpin spiritually and aesthetically as “the eternal spirit of the Blues God.” In the figure of soul-crooner Bobby Blue Bland, sporting Afrocentric clothes and a blues-identified hairstyle, Neal finds a way of dissolving the seeming contradiction between the ancestral African origins, the gut-bucket New World transformations, the freedom-demanding soul extensions, and the pan-African revolutionary consciousness that together constitute the black aesthetic in his eyes. “He was compelled by the evolving/changing critical discourse of his era to go through changes,” Houston A. Baker Jr. notes of Neal, “but in the synapses of all those connections made with Western thought were sounds of an African/Caribbean/New World/Afro-American/Funky-But-Downhome/Journeyed-Back/Gut-Bucket/Honky Tonk changing same called the blues. … He was a pivotal figure in the evolution of a vernacular, blues theory of Afro-American expression in the United States.”54 Neal’s Blues God was an emblem of black cultural survival—“the god that survived the middle passage,” as he put it in a 1978 interview—but also a god of native lyricism, one inflected by the race’s American oppressions. “We are an African people, but we are not Africans,” Neal insisted in “New Space: The Growth of Black Consciousness in the Sixties” (1970): “We are slave ships, crammed together in putrid holds, the Mali dream, Dahomey magic transformed by the hougans of New Orleans. We are field hollering Buddy Bolden; the night’s secret sermon; the memory of your own God and the transmutation of that God. You know cotton and lynching. You know cities of tenement cells.”55

It is striking to compare Neal’s 1970 statements with the program copy for the 1970 Ann Arbor Blues Festival and realize that the Blues Revival, too, was struggling to articulate a version of the Blues God: an ancestral source, indisputably black, yet one in which whites as well as blacks could be baptized. The 1970 program, Exhibit B in the evolving ideology of blues universalism, relinquished Habel Husock’s claims of the previous year that faithful white musicians could refine the blues. This year the ideological core wasn’t “Now that we play the blues, we have made them our own,” but “Now that we listen to your blues, we feel them as intensely as you do.” What the festival organizers felt more than anything was a sense of mourning for the pantheon of black blues performers who had died since the previous year’s festival and whose photographs and capsule biographies were featured in the program: Kokomo Arnold, Slim Harpo, Earl Hooker, Skip James, Magic Sam, and Otis Spann. “Their deaths,” wrote the organizers, “have left a vacancy in our hearts that will never be filled.”56 One might, if one wanted to be irritable, dismiss such effusions as an updated version of the plantation sentimentalism that accompanied the death of a faithful black slave: sadness for the passing of the Old Negroes imbued with nostalgia for an integrationist/paternalist idyll that had been exploded by black social assertiveness in the Black Power era. Or one might decide that real family feeling across racial lines is being evidenced: a beloved black-and-white blues community. Or both. (In this book, as I’ve made clear, I’m trying to hold down the space between black bluesist skepticism and blues universalist idealism.) The roots of the modern “keeping the blues alive” movement, in any case, are visible in the 1970 Ann Arbor Blues Festival program, along with a surprisingly forceful articulation of the black aesthetic:

The Blues will never die. We of the Blues Festival Committee whole heartedly believe this, but we also accept that time changes everything, even the blues. The Ann Arbor Blues Festival is set up as a tribute to an American musical genre that has been part of black culture in this nation since slave days. It is from and of the black experience. Those who bemoan the passing of the so-called rural blues fail to realize that the same intensity and feeling is apparent in the blues that pour from the black urban community today. The blues are the same—only the problems are different. …

We of the festival hope to achieve, as last year, a true rapport between the audience and the performing artist. This shouldn’t be too difficult as this year’s show contains some of the greatest blues acts around.57

“The black experience,” a linguistic marker deployed in the Black Power era for the anti-assimilationist assertion of black singularity, is bent to different ideological purposes here. A critique is implicitly being leveled, for one thing, at folk blues purists such as Alan Lomax and Samuel Charters who had famously denigrated urban blues artists such as B. B. King as too commercial—and whom Charles Keil had skewered so effectively in Urban Blues. Hip white blues aficionados, these program notes suggest, fall into Larry Neal’s camp: they groove to the Blues God’s unities rather than engaging in silly cultism. But Neal’s claim about the Black Arts Movement’s being “radically opposed to any concept of the artist that alienates him from his community” has also been stealthily reworked here: what had been a description of the black performer’s organic relationship with his black public has been transformed into a prophecy about the black performer’s relationship with what would turn out to be an almost entirely white festival audience. What guarantees the “true rapport” between black performer and white audience is a seemingly effortless marriage between black artistry and the emotional response such artistry compels. The social solvent here is white blues feeling, understood as the evoked and adequate correlate to black blues power. Such feeling celebrates a pantheon of black blues gods only to explode the idea of a black nation: an integrationist rather than ethnic-consolidationist ethos. It is counterrevolutionary to the core—if by revolutionary you mean intent on forging a close bond between black performer and black community of a sort that discourages or precludes white participation.

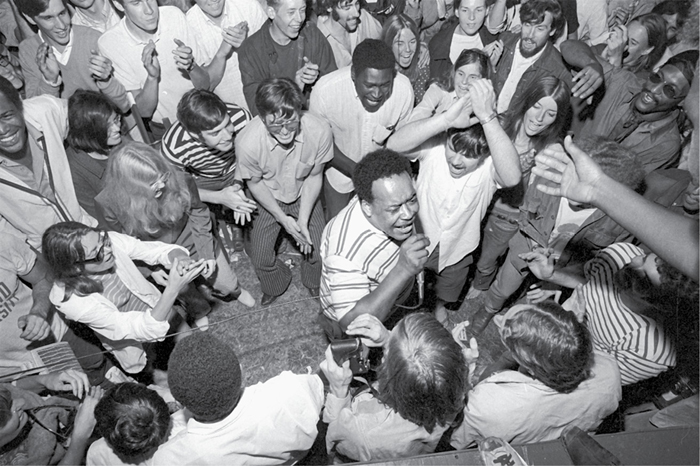

James Cotton and fans at the Ann Arbor Blues Festival, 1969

(© Tom Copi / San Francisco)

It was perhaps inevitable, amid so much ideological struggle, that black blues promoters with sensibilities shaped by the Black Arts Movement would stage their own Blues Revival event. “The Washington [D.C.] Blues Festival held in November 1970,” according to Michael Haralambos, “was the first blues festival produced by blacks for blacks. According to the press handout it was “an attempt to return blues to the black community given that many white interests have exploited the music at the expense of many of the black musicians who will be performing.’”58 The lineup was a treasure-trove of black cultural riches: Luther Allison, Libba Cotton, Sleepy John Estes, Buddy Guy & Junior Wells, Richie Havens, J. B. Hutto, John Jackson, B. B. King, Furry Lewis, Mance Lipscomb, Fred McDowell, Muddy Waters, Rev. Robert Wilkins, and Howlin’ Wolf. The multiday event announced its departure from mainstream festival practice by kicking off, on Thursday evening, with what Jazz Journal’s correspondent characterized as “the volatile and exciting African Heritage Dancers and Drummers[, who] began by taking us back to the African motherland in the highly skilled and rigorous performance of ceremonial dances of West Africa.”59 This prideful framing of the blues as a New World extension of African musical practice was new—a logical extension, perhaps, of the Pan African Cultural Festival in Algiers the previous summer, which had been attended by at least one blues-loving Black Panther, Stokely Carmichael.60 New, too, was the venue: Howard University, which made the festival, according to Jazz Journal, the first such event to be held on a black college campus. What was also new, and at the same time uncannily familiar for black blues advocates during the Blues Revival, was the spectacle of Black Art overrun by white blues fans. “Topper Carew,” reported the Jazz Journal,

(Director of The New Thing Art and Architecture Center which sponsored the event) had hoped to instill pride and interest in the cultural heritage of a 76% black communtiy [sic] of Washington by presenting the blues—the raw-boned music which so essentially encompasses the experience of the black man in America.

Sadly, only a small percentage of blacks were in attendance, sprinkled amongst a predominantly white, hippy crowd who came to listen to the blues and dig the overall scene. The blues are created by blacks but are apparently supported by whites! The magnetic grip of the soul genre, tawdry in comparison with the rugged purity instrinsic [sic] to the blues idiom perhaps has its slick hooks in the young generation of blacks. Or maybe with the growing black pride, the blues are all too unpleasant reminders of a wishfully forgotten past; and understandably so.61

What to make of such a flagrant sociological paradox? If such an event, carefully framed to enable the unembarrassed participation of a politicized young black audience, had failed to draw such an audience, or much of any black audience, it would seem hard to continue to rail, as Stephen Henderson had railed a few months earlier on a different black college campus, against white “cultural cannibalism.” In this case, the culture cannibals shored up somebody’s profit margins, and not a white man’s.

THE BLUES IS ALRIGHT

What is the shared legacy, finally, of the vexed and unacknowledged partnership between the Blues Revival and the Black Arts Movement? One might argue that the disco craze of the mid-1970s helped undo both social formations, dissolving the dirty realism of the former and the ethnocentric advocacy of the latter in a multiracial bath of depoliticized beats-per-minute. The truth, somewhat more complex, allows for a pair of striking generalizations about the past fifty years:

1. White blues fans and musicians have taken blues music—including an ever-shrinking cohort of black blues elders—and run with it, letting (blackened) white blues feeling blossom into blues societies, blues festivals, blues magazines, blues instructional videos, and the like.

2. Black blues writers and cultural custodians, unable to prevent these proliferating appropriations, have taken their stand on the printed page; black literature has become the locus of a fresh, wide-ranging, and profound re-engagement with black ancestral and post-soul blues, a cultural legacy that is effectively off-limits to white writers.

White folks came away from the sixties with the music, in short; black folks came away with the talking books. (White folks also came away with the ghostwriting credits for a series of black blues autobiographies—a genre that requires them selflessly to suppress their own voices so that the voices of their black subjects may emerge.) The result in our own day is a curiously bifurcated blues culture in which hardcore white blues aficionados who can easily list Robert Johnson’s recorded sides (including unreleased alternate takes) and various rumored burial sites draw a blank when literary works such as “The Weary Blues” and Their Eyes Were Watching God are mentioned; a culture in which younger black poets who can name a dozen poems by Langston Hughes, know enough about Albert Murray to reject his cultural politics, and are hip to Jess, Kevin Young, and Harryette Mullen, will draw a similar blank when two of blues music’s brightest young black stars, Jarekus Singleton and Marquise Knox, are mentioned.

Such sweeping generalizations, true as they may be, obscure significant local exceptions. One of these is poet and former White Panther John Sinclair, whose volume, Fattening Frogs for Snakes: Delta Sound Suite (2002), takes a series of interviews with black blues musicians gathered by white journalists over the years and transforms them into a kind of documentary free verse, so that Sinclair’s own poetic voice disappears for long stretches into the voices of Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson, Robert Junior Lockwood, Bukka White. “The book,” insists Amiri Baraka in his foreword, a helpful authenticating document in this post–Black Arts era, “is not a Homage to the Blues, it is a long long long blues full of other blues and blues inside of them. John all the way inside, and he got the blues.”62 A white man has written a literary blues beyond color, it would seem, but also a blues securely anchored in a griotic ambition to sing the black ancestors—Sinclair’s, Baraka’s, ours.

Another exception—in this case, to the hoary truism that blues is no longer a black popular music—can be found in the soul blues scene in Mississippi. In the fall of 2002, shortly after moving down from New York, I attended a heavily advertised show in Canton, a northern suburb of the state capitol. By my count, I was one of four whites in a crowd of perhaps 3,000 blacks, all of whom had come to spread lawn chairs on the dirt infield of an indoor rodeo facility and groove to heavy-rotation soul blues stars Sir Charles Jones (“Love Machine”), Marvin Sease (“A Woman Would Rather Be Licked”), Peggy Scott-Adams (“Hot and Sassy”), and Willie Clayton (“Call Me Mr. C”). The endless round of Chicago shuffles and revivalist acoustic fingerpicking that mark the post–Blues Revival mainstream were conspicuously absent, but blues—as a timbral and microtonal vocabulary, a harmonic home, a familiar place that an otherwise conventional soul composition could suddenly go—was very much in evidence. “Do you mind if I sing you some blues?” Clayton demanded of the crowd midway through his exhilarating set. “Do you mind if I throw a hurtin’ on you?” The deafening roar, the hands raised in willing testimony, the brisk CD and T-shirt sales I noticed later at Clayton’s merchandizing table, all suggest—as Living Blues, to its credit, has been insisting for some time—that blues music for certain sectors of the black community is alive and well, albeit in a form that the mainstream can’t quite bring itself to acknowledge as blues.

A final paradox begs to be considered. The revitalized black market for blues that I’ve just described, roughly thirty-five years in duration, can be traced to two releases, Z. Z. Hill’s “Down Home Blues” (1982) and Little Milton’s “The Blues Is Alright” (1984). Both songs, twelve-bar shuffles of the sort that white blues audiences and musicians had been keeping alive through several decades of black popular neglect, were also, with their roots-and-pride ethos, the answer to a prayer sung by Black Arts spokesmen Neal, Henderson, Welburn, and Karenga: black art for the black community. Both songs were functional, collective, committed to self-respect and spiritual uplift. They were and are popular with whites, too: once they’d broken through, Little Milton worked the mainstream as well as the soul blues circuit, and made a good living doing it; Bobby Rush currently does the same thing. The title of Milton’s song, in fact, was the official motto in the congressionally certified “Year of the Blues” (2003). The blues is alright: not quite the revolution many thought they were having, way back when, but still an achievement worth noting. The Blues Revival and the Black Arts Movement, unacknowledged coconspirators, did indeed transform our world.